ЭкспериментИскусство_2011

.pdfinherent in works of art. This need is inherent in any work of art, i.e., it should appear both in ‘temporal-sequential’ works and ones perceived instantly.

1. Local means supporting perceptual integrity

Let us start our consideration from the simplest case, i.e., works containing temporal sequences which require ‘local gluing’of neighboring elements. The logic of the below classification derived in this Section, is illustrated with Fig. 1. [Naturally, of course, in reality the sets of phenomena belonging to some clusters derived, show overlapping. However, it is not of importance for the logic of the forthcoming analysis.]

To realize local gluing of neighbors, two ways exist:

Aa. It is possible to use ‘natural properties’ of neighboring constituents, i.e., to base gluing on those features which are naturally present in them (irrespective of any special ‘gluing aims’). Of course, the nature of these features depends on a kind of art, genre peculiarities of each concrete work, as well as its concrete contents. For instance, usually a prosaic work consists of episodes forming a plot, each episode describing certain features of the reality depicted. Exactly these features can be used as ‘gluing substance’for our purposes. So adjacent episodes should have ‘something common’ to be glued together. Thus, if a novel is devoted to narration about certain historical facts (e.g., a novel ‘War and Peace’ by Lev Tolstoy, devoted mainly to the war of 1812), then the sequence of different episodes of the narration is not random, and the novel does not go to pieces: it is glued by natural internal logic of the historical process described. As well, in a love story, episodes of the narration can be glued together by their natural logical sequence: from the first rendezvous – to marriage (or divorce, or parting).

Ab. It is possible to use ‘artificial properties’ of neighboring elements, i.e., those additional features which are ‘not obligatory’ for the main structure of the work, local gluing being their special destination. Appropriate devices can be divided into two branches.

Ab1. Rather ‘pronounced’ devices (‘featured features’) which are seen at the first sight. In musical works such devices are presented, for instance, in the form of theme variation, refrain, and so forth. In poetry we see such a ‘well featured’gluing device as rhyme. Apropos, in accordance with the theory of Russian formalists (see, e.g., Arvatov, 1928), rhyme as a systematic poetical device arose

194

A. Problem of temporal sequences and local gluing of constituents; devices

Aa. Basing on ‘natural properties’ of adjacent elements

Ab. Basing on ‘artificial properties’ of adjacent elements

|

|

Ab1. ‘Pronounced’devices |

Ab2. ‘Hidden’devices |

|||||

|

|

|

Problem of the |

Problem of ‘substance’ |

||||

|

|

|

frequency of |

penetrating the entire |

||||

|

|

|

occurrence |

work |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

examples: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Logical links: |

Theme variation |

Associative links |

Sequence |

|||||

historical novel |

refrain, rhyme |

within a stanza |

of temporal |

|||||

(‛War and Peace’), |

|

|

and between |

associations |

||||

love story |

|

|

stanzas (‘Eugeny |

(‘To Ohaadayev’) |

||||

|

|

|

|

Oneguin’) |

|

|

||

Fig. 1. Logical scheme: deducing local means capable of supporting perceptual ‘gluing’ of the work of art

(in late Renaissance West European poetry) exactly for ‘aims of gluing.’When entering the era of book-printing, it occurred desirable to replace previous gluing device, i.e., musical accompaniment which disappeared when turning from songs of bards and minstrels – to printed poetical texts. [Besides, recently the phenomenon of rhyme as a gluing device, together with its principal perceptual parameters, was deduced in the framework of the information approach; the parameters derived were proved in experiments on perception – Koptsik, Ryzhov, & Petrov, 2004; Kamensky et al., 2006.]

All such devices, as well as most of devices described below, are nothing else but repetition of certain elements of the work or their features. The repetition may be either full (tautological) or partial (non-absolute coincidence of elements or features). About strategy of usage of both kinds of repetition see, e.g.: Golitsyn, 1997; Golitsyn & Petrov, 1995; Petrov, 2004, 2005).

Ab2. “Hidden devices”, influencing upon the subconscious realm of a recipient (like the 25th sequence in cinema). An example of such a kind we can find in a novel (in verse) ‘Eugeny Oneguin’ by Alexander Pushkin. Surprising is the giant length of this novel

195

(several thousand lines): such a size is contra-indicated for ‘genuine poetry,’ because its perception should be based on the second step of memory (up to several seconds), and hence the size should be limited by 20 – 30 lines. [About theoretical considerations concerning preferable sizes of literary works, see Golitsyn & Petrov, 1995.] However, this novel does not go into pieces when reading. Why?

The main secret of its integrity is in that the narration is literally penetrated by strong associative links which serve as the above ‘hidden parameters’ used for gluing together adjacent fragments of the narration. [The detailed theoretical consideration of these links in the novel mentioned, and their experimental identification, see in: Petrov, 2003.]

First of all, such associative links are met within many stanzas of the novel. For instance, in Chapter V we read (below an interlinear translation is given, as well as in further examples):

Anaughty boy has frozen his finger: He feels pain, and it makes him laugh,

And his mother reproaches him through the window…

Here the reader sees two almost identical images: at first the boy’s frozen finger, and afterwards his mother’s finger shaking at him. So the tight associative link between the two adjacent images does really appear, and they occurred to be glued. So, such local gluing supports the perception of each stanza as a sensual integrity.

But what is much more important, is that the same local gluing is used at the borders of adjacent stanzas. Of course, each stanza can be perceived as an integrity (as soon as the length of each stanza is only 14 lines). However, there is an important need for gluing together at least adjacent stanzas. And really, in the novel considered, we observe the phenomenon of associative gluing, forming a kind of a ‘bridge’ between adjacent stanzas. For instance, in Chapter V the stanza XLI is concluded by the following words:

...and, a friend of winter nights, Asplinter is crackling before her.

And immediately, at the beginning of the next, XLII stanza we read:

And now frosts cause crackling And make the fields silver…

Obviously, here the two stanzas are glued together by something ‘crackling’ in both stanzas, though in the former stanza the scene is laid at night, and in the latter one in the daytime.

196

We should mention that this device is used not at all inter-stan- za borders. In agreement with the informational model, any ‘hidden device’ used in a certain regular structure (e.g., in a ‘lattice’ of stanzas), should be met, on the one hand, with rather high probability (frequency), in order to influence upon the perception, but on the other hand, its frequency should not step over the threshold of awareness (realizing); otherwise this device will be perceived as importunate, premeditated, i.e., not occasional. In turn, in such regular structure the threshold of realizing should be (Petrov, 2002; Majoul & Petrov, 2000)

A = √ T, |

(1) |

T being the threshold of perception. Meanwhile, there exists a psychophysical regularity concerning rather stable value of T for various kinds of stimuli: about .12 – .15, i.e. the minimal difference perceived is 12 – 15% of the magnitude of any stimulus. Hence, the threshold of awareness A is about .35 – .39. So, to provide optimal perception when working in a certain ‘regular lattice,’ any ‘hidden device’ should be met with the probability close to the threshold of realizing (awareness). It means that the device in question should be used at 30 – 35% of inter-stanza borders. Exactly this optimal share was observed in the experiment on perception of associative links in Chapter I of ‘Eugeny Oneguin’: 30% of interstanza borders were glued by this device. These empirical results are presented by Fig. 2.

Here circles designate stanza (those stanza which are empty, i.e., consist only of dots, are presented in brackets). Out of 50 inter-stanza borders, i.e., potential ‘pretenders’ to gluing devices, 15 borders were really filled by this gluing device (shown by cramps), i.e. 30%. One can see that as a rule, this device is not used two times in succession. The only exception relates to the very beginning of the Chapter (borders between stanzas III and IV, between IV and V, and between V and VI), but just after this frequent usage, a large ‘gap’ appears (as if the poet were in fright of perception of this device as too importunate). So this device is used optimally, and it imparts to the integrity of the work. [Here the device providing integrity, serves also to compensate the contradiction between certain specific features of the work, and genre requirements to its nature. Such ‘joint destination’ should be typical for most devices in question, because it is advantageous.]

197

Fig. 2. The row of 60 stanzas (designated by circles) constituting Chapter I of ‘Eugeny Oneguin’, and inter-stanza associative links (designated by cramps)

Another version of local gluing realized by associative links, relates to a certain ‘substance’ (matter) which penetrates the entire work, enhancing its perceptive integrity. When dealing with works possessing ‘temporality’ (i.e. duration which is important for the perception), such a substance can be played simply by real time. Hence, temporal associations accompanying perception of different fragments of the work, should possess quite definite direction: the sequence of these associations should coincide with the course of the main perception.

Exactly such situation often takes place when a certain narration is devoted to rather abstract matters, instead of concrete sensual images which are required by the genre used. Such a ‘substitution’is contra-indicated for any work of art; again we deal with a contradiction between concrete content of the work and ‘due’ genre requirements! So, in order to ‘allay’ such a contradiction, an artist should resort to the help of the device in question. An experimental investigation of this phenomenon was made on the perception of a poem ‘To Chaadayev’ by Pushkin (1818). Special procedure was derived to measure temporal associations of words constituting this poem, involving 25 participants (12 males and 13 females) each of them having been asked about his/her temporal associations connected with each of 59 meaningful words of the poem: nouns, adjectives, verbs, and proverbs (Golitsyn & Petrov, 1995). It occurred that the

198

overwhelming majority of these words were tightly connected with definite time of a 24-hour cycle. Table 1 presents a fragment of the experimental results obtained: initial 12 lines (out of 21 lines of the poem), together with temporal associations of each word in the group of male subjects (the words which generated these associations, are italicized). For instance, in the 10-th line of the poem, the words ‘minute’ and ‘liberty’ arose temporal associations 8.6 hour and 15.9 hour, respectively, and the word ‘sacred’ showed no rather featured temporal associations. [It was the only word which showed no temporal associations.]

Having these data, it is possible to calculate the mean value of temporal associations for each line of the poem: see the second to

|

|

|

|

Table 1 |

|

Temporal associations generated by initial 12 lines of a poem |

|||

|

‘To Chaadayev’(a group of 12 male subjects) |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

N |

Line |

Temporal |

Mean |

Rank |

associations of |

value, |

|||

|

|

the words, hour |

hour |

|

1 |

Love, hope, and peaceful |

21.6; 4.8; 1.8; |

4.2 |

1 |

|

glory |

12.7 |

|

|

2 |

Not long indulged us as |

11.5; 1.1; 4.6 |

5.7 |

2 |

|

a fraud; |

|

|

|

3 |

Disappeared young |

21.1; 8.8; 19.3 |

8.4 |

4 |

|

amusements |

|

|

|

4 |

Like a slumber, a morning |

3.4; 7.4; 6.6 |

5.8 |

3 |

|

mist |

|

|

|

5 |

But in us a desire is burning: |

20.9; 19.6 |

20.2 |

15 |

6 |

Under oppression of a fatal |

12.0; 22.0; 13.6 |

15.9 |

9 |

|

power |

|

|

|

7 |

Our impatient souls |

18.2; 1.6 |

19.8 |

14 |

8 |

Heed the fatherland’s calls |

20.8; 11.2; 11.0 |

14.3 |

6 |

9 |

We are waiting, with a |

17.8; 20.0; 18.4 |

18.7 |

13 |

|

languor of hope |

|

|

|

10 |

For a minute of sacred |

8.6; –; 15.9 |

12.2 |

5 |

|

liberty |

|

|

|

11 |

Like a young lover is |

10.8; 23.2; 20.3 |

18.1 |

11 |

|

waiting |

|

|

|

12 |

For a minute of a sure |

9.5; 19.5; 18.5 |

15.8 |

8 |

|

rendezvous |

|

|

|

199

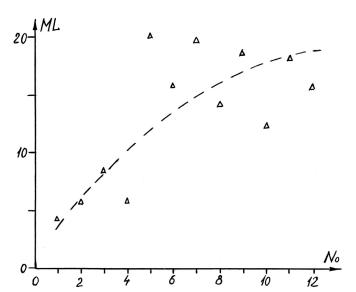

Fig. 3. Mean temporal associations (ML, hours) of 12 initial lines of ‘To Chaadayev’, vs numbers of the lines (No)

right column of the Table. Then let us compare these mean values, with ‘natural’ sequence of lines, i.e., the real time of reading. The co-ordination of these two sequences is illustrated with Fig. 3. One can easily see that when increasing the number of the line, its temporal associations reveal statistical growth. In fact, words of the 1st line ‘love’, ‘hope’, and ‘peaceful’ are usually connected with night or early morning, whereas words of the 9th line ‘waiting’, ‘languor’, and ‘hope’ are associated with the evening. The agreement between the two courses is confirmed by rather high Spearman coefficient of rank correlation: .55, which is statistically significant at 5%-level. [For all 21 lines of the poem, this coefficient equals .78, which is statistically significant at the level better than 1%.] So we do really observe the coincidence of the associative row and the course of perception of the poem.

2. Global integrity: How to achieve it without introducing special substances?

When considering those devices which can be used to integrate the work as a whole, we shall again resort to the help of dividing

200

these possible means into two classes: their substance can be either ‘natural’ or ‘artificial’. [The logic of this Section and the following ones, is illustrated with Fig. 4.] ‘Natural’ substances may be, for instance, certain features which are used in the structure of the work, whereas ‘artificial’substances may be some other features introduced especially (though possibly unintentionally) in the work, to increase its integrity.

Ba. The ‘raw material’ for natural substances capable of integrating the work, is contained in its constituents themselves. How to apply them for this purpose?

Here the problem arises which was absent when we spoke about local gluing. The problem is which exactly constituents should be linked for creating the unity desired? [In the case of local gluing these constituents were obvious: simply adjacent elements, i.e., ‘immediate neighbors’.] However, this problem presupposes another one: maybe, in some cases all constituents (or most of them) occur to be linked ‘automatically’ by a certain ‘common matter’? Hence, in general two problems arise, responding to two possible ways capable of providing perceptual integrity:

Ba1) due choice of the entire set of constituents for the work; Ba2) due ordering of those constituents which should be

linked.

The first way (Ba1) means nothing else but the decision made by an artist either consciously or not, concerning compiling the work of such elements which would constitute his/her work. Here again two versions are possible, in dependence of the reasons which are capable of generating the perceptual integrity:

Ba1α. External roots: the integrity can be caused by specific choice of the position of a recipient in relation to elements perceived. The best position for such integral perception ‘embracing’all the elements, is sometimes (though rather seldom) met in our everyday life: it is nothing else but the position at the top of a mountain. In such a case all the objects below are seen simultaneously, they are spread before the eyes, and many writers describe this view.

In literature we also sometimes meet such a specific position which permits – mainly due to its originality – to integrate all the elements depicted, so they would be perceived as a certain integrity. For instance, in the First Chapter of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ by Jonathan Swift, all the world is seen from the position of a giant, as if the world of Lilliputians were observed from a certain ‘top.’ On the contrary, the world in another chapter is seen from the standpoint of

201

Fig. 4. Logical scheme: deducing means capable of providing global integrity of the work

a quite small person, and the originality of this worldview imparts the features of integrity to the narration. In a story ‘Notes of a Madman’ by Nikolay Gogol, a part of the narration has a form of a diary written by a little dog Medzhi; this original standpoint helps to integrate the description of the events in the story. Such a device was used by many prose-writers.

202

In fine arts, such integrating role of a position is often played by means of a system of the perspective. In the case of the figurative painting, when an artist depicts a certain fragment of space, he/ she should inevitably resort to the help of one of possible projective systems (see Rauschenbach, 1980):

–direct perspective; here parallel lines going from spectator to the infinity, converge in the infinity, or at least very far from the spectator; such a system is typical for Renaissance and contemporary West European painting;

–inverse perspective, when these parallel lines converge in the eye of a spectator; such a system was typical for medieval European painting;

–various kinds of parallel projections, e.g., so-called ‘axonometric’ one, without any convergence of parallel lines, as it was in some genres of traditional Japanese painting, etc.

In each case, subduing to requirements of a definite system of projection, an artist assists a spectator to perceive the work as an integrity.

Ba1β. Another situation takes place when internal roots can cause the integrity: such special choice of a set of elements involved,

which is capable of ‘automatically’providing their perceptual integrity. In this case, the elements should form a net of internal links, this net being so tight that it is perceived as a ‘closed world.’ In prose such situation is met especially frequently. For instance, in the novel ‘Vingt ans après’ by Alexander Dumas, the main personage D’Artagnan galloping at full speed, knocks down a passer-by; however, this passer-by is a Parliament councillor Broussel, which has a servant Friquet, in turn, the last one is watched over by Bazin, who is a servant of Aramis, a friend of D’Artagnan.

As well, such tight net is frequently met in paintings: e.g., when an artist compiles a set of objects for his/her still-life, as a rule, those objects are chosen which are linked with each other on various parameters. Apropos, that is why even an artist belonging to abstractionist (absolutely non-realistic) branch of painting, if creating landscapes, prefers to proceed from concrete observations: in fact, the reality is penetrated by numerous ‘natural links’ (shadows, reflections, interwoven conscious and subconscious interactions of different objects, etc.), which are capable of integrating the picture.

Ba2. Turning to the second way of creating integrity basing on due ordering of ‘natural’ elements, we find here the main problem:

203