ЭкспериментИскусство_2011

.pdf

Таблица 3 (окончание)

III

Ключевые идеи: приятные чувства, цветы ассоциируются с теплыми семейными отношениями или с гармонией

Респондент 4 |

Респондент 1 |

|

|

«Очень приятная и естественная. |

«Рабочий стол ученого, у кото- |

Живые цветы милые, они ожив- |

рого теплые семейные отноше- |

ляют картину. Цветы – это то, что |

ния. Изучает смерть для помощи |

объединяет с природой, создают |

окружающим, чтобы продлить |

гармонию» |

жизнь» |

|

|

Вероятность появления интерпретации 0,2

IV

Ключевая идея: на картине символично изображен конец некоторого этапа и начало следующего

Респондент 9

«Цветы живые. Это видно, цветы весенние. Это конец одного этапа, жизнь продолжается. Это продолжение»

Вероятность появления интерпретации 0,1

создавая зрителю возможность выделить новые смыслы бытия, поднимает его и духовно возвышает (конечно, на высоту, пропорциональную таланту живописца). Но эта работа по осмыслению и осознанию сотворчества зрителя творцу произведения искусства скрыта (по крайней мере в настоящем) от исследователя, и никакие формы объективизации (типа движения глаз или анализ динамики кожно-гальванической реакции зрителя) не в состоянии ее объективизировать. Тем не менее мы полагаем, что развитие психосемантики ментальной картины мира, психосемантики творческих процессов и психосемантики самосознания способно приоткрыть дверцу в «мастерскую духа» и исследовать визуальную герменевтику восприятия живописи.

Stefano Mastandrea

Psychological suggestions to design perfect objects

Differences between artworks and industrial design objects

Traditional artworks like paintings, sculptures, etc., need to be experienced aesthetically, that is in their form rather than in their functions. An artwork does not have a practical function; it is created with the aim to perform aesthetic meanings (Panofsky, 1955). Cognitive and affective processes can be aroused by its form, colour, material and texture (Mastandrea et al. 1993). On the contrary, an industrial design object has the fundamental purpose to respond to practical functions (Arnheim, 1964); for instance a chair must be comfortable and stable. But beyond this an object must have also a certain level of aesthetic function in terms of being appealing, beautiful, and attractive.

Another difference between these two categories (artworks vs. I. D. objects) is that I. D. objects cannot be created with just any kind of shape. Creating an object requires many structural constraints: for example, an industrially produced chair must have at least three legs (because with less than three legs you fall down), but for our safety is better four; on the other side, the artistic drawing of a chair can have as many legs as the author desire; it has to respond only to aesthetic aims and not to practical functions.

The designer works in groups, with a deep knowledge of the materials and the technology of the industrial world. One of his aims might be to create a mass-produced object, at a low price, for wider aesthetics dissemination.

The artist works mainly on his own, with subjective ideas and high degrees of freedom if not total. On the other hand the designer must be more rational, overly logical and has to justify everything he does. However there can be a common ground for both: a work of art or an object must be innovative and original to become an art craft.

155

The Industrial Design (I.D.)

To satisfy our needs we constantly use objects of any kinds, with different shapes, colors and materials. Without these objects it would be not impossible, but more difficult to live. Everyday new objects are produced to try to satisfy our several necessities. We buy objects not only to satisfy our functional needs but also for aesthetic and affective motives. Moreover, I.D. objects must be market competitive. This means that the production of an object must be closely linked to its economic aspects (investment of capital for the production cycle). There are also aspects of social nature depending on the symbolic value of these objects in terms of status acquisition and identity reinforcement: the possession of a certain object can communicate to others some aspects of the self identity and the belonging to a specific social group.

How to create a good object

It is not easy to define what requirements an object must have to be defined a good designed object. From the functional point of view, according to Norman (1988), there are some principles that must be followed to create a good product. These principles are: visibility, affordance, mapping and feedback.

Visibility. The parts of an object that have a function must be visible and must convey the right message. By watching the object the user can understand which actions he has to perform in order to be successful with its correct use.

Affordance. The term affordance was first introduced in 1977 by the psychologist James J. Gibson. An object must communicate the use through its structural characteristics. Norman considers the example of different door handles.Aperson should understand if the door must be pulled or pushed only by looking at the handle. If one sees a typical handle, it is difficult to understand which operation must be performed to open the door: push or pull? But if one sees a simple metal plate on one side of the door, it is possible to understand immediately that the door must be pushed. The affordance is that set of actions that an object “invites” one to make it, as it allows to infer its functionality by the operating mechanisms.

Mapping. The term mapping refers to the spatial relationships between action and result. If you want to go right with your car, you turn the steering wheel to the right; but if you are sailing a boat you have to turn the steering to the left. In the first case there is a natural

156

mapping between your action and the result, while in the second case there is an incongruence. When possible, it is always necessary to use a correct mapping. The correlations between the commands and actions must be clear to those who use them. According to Norman, mapping problems are a major cause of our difficulties with the objects.

Feedback. It is the feedback that tells the user if the operation he performed has achieved the aim. When you dial the numbers on a cellular phone the beep sound tells you that you have pressed a button; when you see the number that you dialed on the display you have a feedback of your action. When is possible is better to have feedback

Wecanstatethatthemore“legible”thefunctionalcharacteristics and the aesthetic meaning of an object are, the more successful the I.D. of the object is.

In Norman’s book “The Design of Everyday Things” (1988) the author highlights the existence of three different mental models that we have to consider when we deal with an object. The first is the designer’s model and it has been developed by the designer to create a functional object. The second is the user’s model, developed through the interaction with the object, observing and using it. The thirdsystemcomesfromthephysicalstructureandthecharacteristics of the object. The designer expects the user’s model to be identical to the design model, but the designer does not talk directly to the user, all communication takes place through the system image of the object. If the object and the image system does not make the design model clear and efficient, then the user will end up with the wrong mental model and probably he will fail when he has to use the object.

Function and expression of objects

For Arnheim (1949) the psychological function of the objects is essentially expressive in nature. In the sense that any object must be able to communicate its formal characteristics not only through its function but also its aesthetic and expressive qualities.

Arnheim (1949) defines the expression as the psychological equivalent of the dynamic processes that are present in the organization of the perceptual stimuli. So are the objects that carry within them the expressiveness. What expressiveness is will be clear with a famous Arnheim’s example: a weeping willow is seen as

157

sad not because it looks like a sad person, but because of its shape, its suppleness, its passive tilt impose a structural configuration similar to that of sadness in humans.

The questions still present for anyone involved in design (in terms of both teaching and working as a designer) are essentially the following: How does the shape of an object can communicate his function? How

does the appearance of an object can reflect its physical function? The recognition of an object may be the result of two main types of processing: a “top-down” and a “bottom-up” processing. The topdown processing is an elaboration based on mental representations of the object (the information contained in memory by the observer is also called “conceptually-driven processing”). The bottom-up processing is based on an analysis of the features that are present in the stimulus and is guided by sensory data. In general, we can say that the application of these two processes depends mainly on two factors: the degree of knowledge that the observer has of the object in question, and the context in which it is placed. If the observer has a good knowledge with the object in question, he is likely to employ top-down processing of the stimulus configuration because he will be guided by a previously acquired knowledge about the object. But if the viewer does not know the object in question, or has little experience of it, he will proceed with an analysis of its characteristics (bottom-up) to achieve identification.The other factor that influences the type of processing used in the identification of an object, is the context in which it is placed. If the item in question is congruent with the context, object recognition processing will be more determined by top-down processes. It is evident that bottom-up and top-down processes are closely linked to other cognitive functions such as attention, memory, imagination and language that are working as an integrated system of information processing.To better understand these points I will take into consideration two objects belonging to the same category, but with very different shapes and modalities of functioning. The category is the squeezer. The first object is a very traditional one (see fig. 1); it is structured in two basic elements:

158

the top part is the squeezer and the bottom part is the container to collect the juice. Cognitive processes involved in the recognition phase of the object are mainly top-down. Information coming from the object is sufficient to understand what kind of object is, due to very similar objects encountered in our past experience.

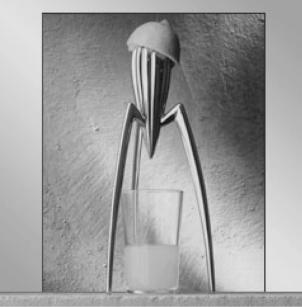

In the case of another object belonging to the same category of squeezer, recognizing the identity and understanding the use is much more difficult (see fig. 2)

If we have never seen before the Philippe Starck’s squeezer, it is almostimpossibletounderstandwhatisthisobjectfor.Theelementsthat constitutes the different operational part of the object are very deeply changed compared to more traditional object of the same category. The

Fig. 2. Philippe Starck. Juicy Salif, Alessi, 1990

159

Fig. 3. Philippe Starck. Juicy Salif with explanation of the use

squeezer on top is still visible but without a juice container does not seem to have the same function.This object looks like a sculpture. Juicy Salif completely modify the typical Bauhaus slogan, “Form follows function” (Arnheim, 1927). It is possible to understand its real meaning only if we add some other components of the whole squeezing process: a lemon and a glass to contain its juice (see fig. 3).

It’s a zoomorphic object, not easily identifiable. Its formal elements are contrasting: curved and smooth shape versus sharp elements. Starck modify the morphological characteristics of a normal squeezer. If we confront the Starck’s object with a traditional one (fig. 1) we can clearly perceive the difference.

Starck’s objects have not been designed to solve a practical function but to be experienced aesthetically, in their forms rather than in their functions. I understand that Starck’s poetics is too extreme and radical, but I believe that to some extent, this is the key to create nice design objects, with a main focus on the function and the correct use of the object, but at the same time a deep attention to the aesthetic features of the objects.

160

References

Arnheim, R. (1927). Das Bauhaus in Dessau. Die Weltbühne, 23, 920-

921.

Arnheim, R. (1949). The Gestalt theory of expression. Psychological Review, 56, 156-171.

Arnheim, R. (1964). From function to expression. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1, 23-41.

Gibson, J. J. 1977. The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology

(pp. 67-82). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mastandrea, S., Zani, A., Giuliani, M. V., & Bove G. (1993). Meaning of industrial design objects: from designers to users. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 20 (3), 307-319.

Norman, D.A. (1988). The Design of Everyday Things. New York: Doubleday.

Panofsky, E. (1955). Meaning in the Visual Art. Garden City, NY:Anchor Books.

Н.Б. Зубарева, П.А. Куличкин

Современный композитор: теоретические взгляды и творческая практика.

От «ноктюрна водосточной трубы» до «бабушкиных аккордов»

А вы ноктюрн сыграть могли бы

на флейте водосточных труб?

Владимир Маяковский, 1913

Желаю «бабушкиному аккорду» дальнейшего процветания и достойных последователей.

Пауль Хиндемит, 1938

К дьяволу бабушек, давайте писать музыку!

Сергей Прокофьев, 1938

Постановка проблемы

Складывается впечатление, что значительная часть современных музыковедов неспособна анализировать современную музыку без помощи авторов этой музыки. Если современный композитор пока еще жив, он почти в обязательном порядке подвергается самому настоящему «допросу с пристрастием». Музыковеды (особенно начинающие) желают знать не только где, когда, в каких обстоятельствах и по какому поводу было создано сочинение, но и самым подробным образом расспрашивают композитора о форме сочинения, о его технике, об идеях и т.д. В свою очередь, композиторы (особенно честолюбивые) часто не упускают случая рассказать о том, какие приемы они использовали, какие техники создали и что нового внесли в мировую музыкальную культуру.

Впрочем, если композитор уже перешел в лучший из миров, даже это не спасет от рентгеновского зрения ревностного

162

исследователя. Ввиду отсутствия возможности личного общения последний подвергнет истязаниям все печатные и непечатные труды композитора и, безусловно, найдет нужные ему высказывания. А уже из этих высказываний будет сделан вывод о форме и содержании сочинений покойного автора.

Подобная «исследовательская традиция» сегодня настолько распространена, что существуют даже докторские диссертации, посвященные исключительно тому, что композитор думает

освоей музыке. При этом часто как-то совершенно забывается тот факт, что создание музыкального произведения (чем занимается композитор) и анализ музыкального произведения (чем занимается музыковед) – это две, по своей сути, различные сферы деятельности. И относиться к словам композитора

особственной музыке как к истине в последней инстанции, в общем-то, нельзя. А то, что тот или иной композитор является еще и серьезным теоретиком (даже когда речь идет лишь о его собственной музыке), – не априорный факт, а утверждение, требующее доказательств.

Конечно, попытки начинающих музыковедов переложить весь груз аналитической работы на хрупкие плечи исследуемого современного композитора, в общем и целом, понятны. И миф

отом, что лучшим экспертом при анализе музыкального произведения является его автор, так или иначе возник. Но… так ли это?

Поэтому в связи со сложившейся ситуацией вокруг исследований о современной музыке естественным образом возникает следующий вопрос. Влияют ли на творческую практику того или иного композитора его теоретические взгляды или нет? И если влияют, то как?

Здесь нам необходимо сделать следующее замечание. Говоря о теоретических взглядах композитора, мы говорим не о теории вообще и даже не о взглядах композитора на те или иные вопросы теории музыки. Мы говорим о теоретических трудах композиторов, в которых излагается авторское учение о технике современной композиции, оформленное в виде трактата (манифеста, декларации и т.п.).

Дело в том, что музыкально-теоретическая подготовка как таковая, безусловно, является частью квалификации любого композитора. И взглядов на то, какой должна быть современная музыка, у композитора не может не быть. Собственно, он и формулирует эти взгляды в своих сочинениях, в результате чего

163