grammatical foundations

.pdf

Check Questions

Check Questions

1Discuss how it is possible to conceive of linguistic knowledge and what is meant by the ‘grammar’ of a language.

2Define the terms ‘arbitrariness’, ‘lexicon’, ‘word category’ and explain how they are related.

3Discuss some general ways of determining word categories and potential problems that may arise in connection with them.

4Explain how the properties of a predicate determine argument structure.

5What is meant by argument structure and subcategorisation frame? Show how it is possible to establish different subtypes of verbs. Support your answer with examples.

6What subtypes of nouns can be established using notions like ‘countable’ and ‘uncountable’ and how may members of the latter be made countable?

7Can the possessor be conceptualised as an argument? Justify your answer: if yes, why; if not, why not

8How is categorial information stored in the lexicon?

9What evidence is available for collapsing the categories Adjective – Adverb? Discuss the behaviour of the -ly morpheme and list some irregularities. In what respect do the categories Adjective – Adverb differ?

10Compare the complementation of N, V, A and P.

Test your knowledge

Exercise 1

Given the two main parts of a sentence subject and predicate, chop up the sentences below into their parts. With the help of the grammatical functions subject, direct object, indirect object, adverbial, divide the sentences into even smaller units.

(1)a Peter met Mary in the park yesterday.

bHe gave Mary flowers when she greeted him.

cMary put the flowers into a vase at home.

dThe man who lives next door saw that they met.

eThat Peter and Mary met surprised everyone.

fThe curtains extended to the floor.

gHe hasn’t finished reading the book she lent him.

hMary has become a teacher.

iPeter lives in Paris.

jMary is in Paris at the moment.

51

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words

Exercise 2

Identify the arguments in the following sentences.

(1)a Peter left his family.

bPeter left after dinner.

cPeter and Mary met in the park.

dMary suddenly noticed that her purse was missing.

eBefore leaving the house she checked her bag.

fThe purse was on the kitchen table.

gPeter considers Mary beautiful.

hJohn knew that Peter and Mary met in the park in the afternoon.

iJohn knows Mary.

jPeter wanted John out of the room.

kThey treated their guests kindly during their stay.

lPeter wrote a letter to Mary the other day.

mHe sent her a box of chocolate, too.

nPeter called Mary yesterday.

oJohn called Peter a liar.

Exercise 3

Here is a list of definitions of theta roles. Given the definitions, label the arguments in the sentences below.

Agent: the participant who deliberately initiates the action denoted by the verb (usually animate).

Theme: the participant (animate or inanimate) moved by the action.

Patient: an affected participant (animate or inanimate) undergoing the action (the roles ‘theme’ and ‘patient’ are often collapsed).

Experiencer: the participant (animate or inanimate) that experiences some (psychological, emotional, etc.) state.

Beneficiary/Benefactive: the participant that gains by the action denoted by the verb. Goal: the participant towards which the activity is directed.

Source: the place from which something is moved as a result of the action. Location: the place in which the action or state denoted by the verb is situated. Propositional: clausal arguments have the propositional theta role.

(1)a Peter loves Mary.

bPeter knows Mary well.

cThe door opened.

dThe purse was stolen.

eMary wrote a letter to John the following day.

fJohn received a letter from Mary.

gMary cut the cake with a knife.

iThere arrived some visitors.

jMary was cooking dinner when they entered.

kPeter has broken his leg.

52

Test your knowledge

lPeter has broken a vase.

mIt surprised everyone that the visitors arrived.

nThey wondered what to do.

oMary is beautiful.

pJohn is in Paris.

qThat the purse was stolen shocked everyone.

Exercise 4

Give sentences according to the following patterns:

(1)a N+V

bN+V+N

cD+N+V+V+P+D+N

dD+N+V+D+N+P+D+N

eD+V+NEG+V+C+D+V+V+D+N

fD+Adv+V

gAdv+N+V+D+N

hN+Adv+V+D+N

iN+V+D+N+Adv

jV+D+Adv+V+P+N

kN+V+P+D+N+P+D+A+N

lD+A+N+P+D+N+V+Adv+A

mN+P+N+V+A+N

nN+V+D+C+D+V+Adv+V+P+N

oD+A+N+V+D+A+N

pD+N+V+V+A

qD+Adv+V+P+A+N

rD+N+V+A

Exercise 5

Give two examples for a one-place predicate, two-place predicate and three-place predicate.

Exercise 6

Identify the thematic and the functional categories in the following sentence and give the feature matrix of each item by making use of the following features [±F], [±N] and [±V]:

The boy in the neighbourhood may have made a big mistake.

53

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words

Exercise 7

Mark the morphological boundaries and state whether the underlined morphemes are inflectional or derivational in the following words.

(1)a easier

bgrandfathers

cunhappiest

dfailed

eunemployment

fwants

geatable

hquickly

Exercise 8

Identify the part of speech of each word in the sentences below.

(1)a John likes eating nice food.

bThe workers must have built the bridge near Boston.

cA friend of mine gave a book to John’s brother.

Exercise 9

The following word forms can have more than one grammatical category. State which these categories are and create sentences in order to show their different distribution.

(1)a leaves

blead

ccosts

dfly

erings

ftears

gwater

hrules

ipresent

jmine

kleft

llong

mfast

54

Test your knowledge

Exercise 10

Identify the word categories in the following sentences and give the lexical entries of the verbs, auxiliaries and degree adverbs as well.

(1)a The pretty girl will surely go for a luxury holiday in Haiti with a very tall

young man.

bHis excellent idea about trade reform can probably change the economic situation of African countries.

cA very big picture of old buildings has been sent to the former president of the electric company in Southern France.

dThe spokesman announced that the most modern houses may have been built

in the centre of London for a year.

fThe ancient ruins might have been destroyed by the biggest earthquake of the century.

Exercise 11

Identify the embedded clauses in the following sentences. Classify them according to whether they are finite (F) clauses or non-finite clauses (N).

(1)a I think that John saw Hugh.

bJohn was anxious for Hugh to see him.

cThey are anxious for they got bad news from their daughter today.

dMy father asked me to go the shop and get him tobacco.

eYou will not get any tobacco from me for you only a child.

fThe buyer wanted me to buy the horse from the seller.

gThe horse I bought yesterday belonged to my brother’s best man.

hThe landlady will go upstairs to clean the rooms.

iWe saw John & Hugh going into their friend’s house a while ago.

jDid you see the woman that I was talking about?

kThat Mary has a headache every day does not surprise anyone.

lI asked you to go.

mFor him to stay would be unwise.

nTo leave the party was very smart.

Exercise 12

Sentences (1a–h) below are all grammatical. On the basis of the examples, provide the lexical entry for each underlined predicate.

(1)a My brother ate a lot of chocolate.

bJohn is keen on wild animals.

cJohn gave a book to his friend.

dHe always parks his car near a nice old hotel.

eI love Vermeer’s painting of the young girl.

fJane broke the vase.

gThe vase broke.

hEverybody got a letter from the Prime Minister.

55

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words

Exercise 13

Give the lexical entries of each predicate of the following sentences.

(1)a The inspector realised that the key could not open the box.

bThe baby crawled from her mother to her father.

cJack thought that the storm broke the window.

dShannon travelled from Paris to Rome.

eLucy cut the bread with a knife.

fMy friend wrote to me that John loved Eve.

gJohn told a story to Peter.

hJohn told her that his mother was afraid of spiders.

iSarah is proud of her sons.

jYoung people are often keen on sciences.

kMrs Smith is always angry at her neighbours.

lSome astrologists have always held the belief that the Sun moves around the Earth.

56

Chapter 2

Grammatical Foundations:

Structure

1 Structure

1.1The building blocks of sentences

So far we have been discussing the properties of words and have said hardly anything about larger units of language such as sentences. A sentence is obviously made up of a number of words, but as we pointed out in the previous chapter, it is not true that sentences are formed simply by putting a row of words together. If this were so then we might expect positions in a sentence to be identifiable numerically, but this is not so:

(1)a Sid saw Wendy

b yesterday Sid saw Wendy

In (a) we have the verb in the second position, with one of its arguments (the experiencer) to the left, in first position, and another of its arguments to the right in the third position. In (b) however, everything moves one step to the right to accommodate the word yesterday which now occupies first position. The point we made previously is that the ordinal placement of a word in a sentence is unimportant as it is clear that the words Sid, saw and Wendy are in the same grammatical positions in both sentences, even though they are in different ordinal positions in the string of words.

This then raises the question of how grammatical positions are defined, if not linearly. To answer this question we must first acknowledge the existence of units in a sentence which are bigger than words. Let us start with an observation that we have already noted, without much discussion, that a sentence might contain another sentence. Consider the following sentences:

(2)a Geoff jeopardised the expedition

b Kate claimed [Geoff jeopardised the expedition]

It is fairly clear that the bracketed part of the sentence in (2b) is the exact same sentence as stands alone in (2a) and that the elements that they contain are in the same positions in both cases. It therefore follows that (2b) is not simply a string of words, but has a structure whereby it is made up of things which themselves are made up of other things. We can represent this situation in the following way:

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

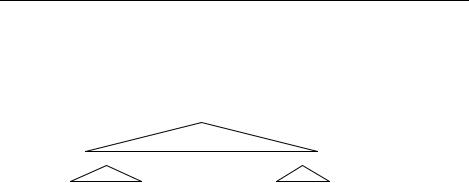

(3) |

sentence |

sentence

Kate claimed

Geoff jeopardised the expedition

If it is grammatical for one sentence to contain another, then it follows that the contained sentence can contain another sentence and indeed that that sentence can contain another, etc. In fact there should be no limit to how many sentences can be contained one within the other. That this is so is exemplified by nursery rhymes of the following kind:

(4)a this is the house [that Jack built]

b this is the malt [that lay in the house [that Jack built]]

c this is the mouse [that ate the malt [that lay in the house [that Jack built]]]

d this is the cat [that chased the mouse [that ate the malt [that lay in the house [that Jack built]]]]

e etc.

Potentially, this rhyme might go on forever, limited only by the parent’s imagination and the fact that their children will one day grow up and want to listen to pop music instead. One might argue that no one could ever produce an infinitely long sentence as they would forget what they were saying after a relatively short time, and for the same reason no one would be able to understand it. Furthermore, they would die before they got to the end of it. Admittedly it would be a fairly pointless thing to do, but that is not the issue. Facts about people’s imagination, their likes and dislikes, their attention spans and even their mortality have nothing to do with the language system. This is, as we have pointed out, a set of rules that enables us to produce and understand the linguistic expressions that make up an E-language.

Now, if those rules tell us that sentences can contain sentences then it follows that infinitely long sentences are grammatical regardless of whether or not anyone could ever produce or understand such a sentence due to external considerations.

Indeed, there would be no point in adding limitations to the grammar to make it fit with these other limitations. For example, suppose we determined that sentences with more than 9 other sentences embedded in them go beyond the human mental capacity to process (it is clear that it would be virtually impossible to come up with a definite number which was applicable to all humans on all occasions – when I get up in the morning, for example, my capacity to process sentences seems to be limited to one! – but for the sake of the argument let us assume this number). Let us pretend, nonetheless, that the grammar is limited to producing only 9 or less embedded sentences. This would be an extra complication to the grammatical system as it adds a limitation to it. Yet the situation would be exactly the same if we did not add the limitation: humans would still be able to process sentences with 9 or fewer embedded sentences, because of their mental restrictions, no matter what the grammar was capable of defining as grammatical. So the extra complication to the grammar would

58

Structure

achieve nothing and we would be better off not adding it and keeping things simpler. Moreover, why would we want to make the grammar explain facts that had nothing to do with it: it would be like trying to get the laws of gravity to explain why red balls fall to the ground at the same speed as blue ones do.

Let us therefore assume the grammar to contain a rule which informally might be stated as follows:

(5)a sentence can be made up of (at least) words and sentences

This rule defines sentences in terms of sentences and so the definition refers to what is being defined. A rule that does this is known as recursive, and recursive rules have exactly the property that we want to be able to define human languages. Recall from the discussion in Chapter 1, human languages are limitless and yet they must be defined by a finite set of rules as the human head can only store a finite amount of information. If I-languages are made up of recursive rules, then a finite set of these will be capable of defining an infinite number of expressions that make up an E-language.

The rule in (5) can be stated a little more formally in the following way:

(6)sentence → word*, sentence*

This rule introduces a number of symbols to replace words used in (5). The point of this is to make properties of the rules more obvious. Recall that generative linguists insist on making their grammars explicit so that we are able to test and question the assumptions being made and it is easier to see properties of rules when stated as a formula than it is if they are given as a set of linguistic instructions, especially as the rules become more complex.

We can read the rule in (6) as follows. The arrow indicates that the element on the left (sentence) is defined as being made up of the elements on the right (word*, sentence*). The asterisk after word and sentence indicates there can be any number of these elements. Thus the rule states that a sentence can be made up of a sequence of words and a sequence of sentences.

At the moment, this is not a particularly accurate rule as it is not the case that English sentences are simply made up of sequences of words and sentences without further restrictions. We have introduced it purely for expository purposes. To make things more accurate we need to introduce another concept.

1.2Phrases

We have said that a sentence can consist of a predicate and its arguments. So in a sentence such as (7):

(7)Prudence pestered Dennis

we have the verb pestered as the predicate which relates the two arguments Prudence, the agent and Dennis, the patient. Now consider a slightly more complex case:

(8)the postwoman pestered the doctor

This could mean exactly the same thing as (7), on the assumption that Prudence is a postwoman and Dennis is a doctor. In this case the arguments seem to be the postwoman and the doctor, a sequence of words made up of a determiner followed by

59

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

a noun. But what status do these sequences of words have in the sentence? It seems as though they function as single words do in (7), inasmuch as they constitute the same arguments as Prudence and Dennis do. Thus these two words seem to go together to make up a unit which is the functional equivalent of the proper nouns in the original sentence. This unit is called a phrase. We can represent this as follows:

(9) |

sentence |

|

phrase |

pestered |

phrase |

the postwoman |

|

the doctor |

Thus, a sentence has more internal structure to it than we have so far been assuming. Not only can sentences contain words and other sentences, they can also contain phrases.

To make the drawing of the structures clearer in what follows we will use the symbol S to stand for sentences and the symbol P to stand for phrases. Though it should be made clear that these symbols have no place in the system we will eventually develop and are used now as mnemonics which stand for something we have yet to properly introduce.

Two questions arise immediately: do sentences contain any more phrases than those indicated in (9), and what can phrases contain? To be able to answer these questions, we must first look a little more closely at the properties of phrases in general. The first thing to note is that just as words have distributions in a sentence, so do phrases. This is obvious from the above example, as the phrases the postwoman and the doctor distribute in the same way that the nouns Prudence and Dennis do: wherever it is grammatical to have Prudence it will be grammatical to have the postwoman and where it is ungrammatical to have Prudence it will be ungrammatical to have the postwoman:

(10)a Prudence is considerate b I saw Prudence

c they spoke to Prudence d *we Prudence Dennis

the postwoman is considerate I saw the postwoman

they spoke to the postwoman *we the postwoman Dennis

With this in mind, consider the following:

(11)a Prudence pestered Dennis on Wednesday b Prudence persisted on Wednesday

It seems that in the position where we have pestered Dennis we can have the verb persisted. This is not surprising as the verb pestered is used transitively in (11a), with a nominal complement (Dennis) whereas persisted is used intransitively in (11b), without a complement. However, if intransitive verbs distribute the same as transitive verbs plus their complements, this means that transitive verbs and their complements form a phrase that has a distribution in the same way that a determiner with its nominal complement distributed like certain nouns. Thus a more accurate description of the sentence than (9) would be:

60