grammatical foundations

.pdf

Why the Noun is not the Head of the DP

There are syntactic reasons, then, for considering these phrases to be headed by the preposition and thus it seems better to assume that the most important semantic word is not always the syntactic head.

A second observation that might support the assumption that the noun and not the determiner is the head of the phrase is the fact that the noun contributes features which play a role in interpreting the meaning of the whole phrase:

(8)a the mouse b the mice

In (8a) the whole phrase is considered to be singular and in (8b) the phrase is plural, as can be observed from facts concerning verb agreement:

(9)a the mouse is eating the cheese b the mice are eating the cheese

As is is the form of the verb ‘to be’ that agrees with a third person singular subject and are is the form agreeing with a third person plural one, we can conclude that the phrases sitting in subject positions have these properties. Thus it would seem that the noun projects its number features to the whole phrase. We have said that projection is something that concerns heads and so this might be taken as evidence that the noun is the head.

Again, however, this is not an entirely unproblematic assumption. Many determiners carry number features of their own:

(10) a |

these people |

*these person |

plural determiners |

|

b |

all answers |

*all answer |

|

|

c |

each prescription |

*each prescriptions |

singular determiners |

|

c |

an occasion |

*an occasions |

||

|

In these cases both the nouns and the determiners are marked for number and so it is difficult to say where the number feature of the whole phrase is projected from. Indeed, even in those cases such as (8a) and (8b) where it looks as though the number is projected from the noun, we could argue that the determiner the is ambiguously marked for singular or plural and, like the other determiners, when it is singular it can only accompany a singular noun and when it is plural it can only accompany a plural noun. The issue therefore rests on which we take to be the head: the determiner or the noun. For this reason, we cannot use these observations to argue in favour of one or the other having head status but we must look elsewhere to resolve the issue.

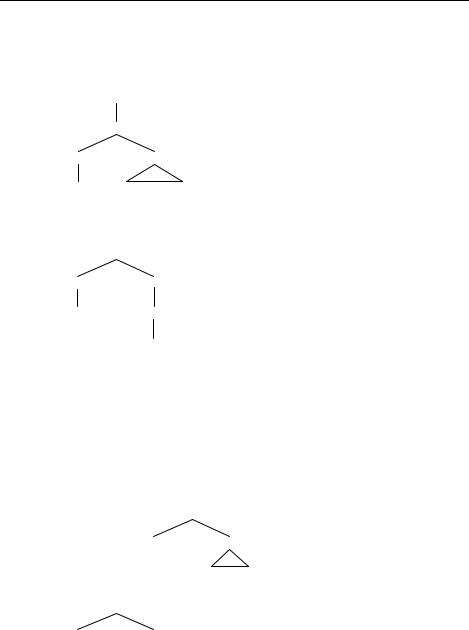

The assumption that the determiner is not the head leads to further problems for the analysis of determiners and pronouns themselves. First consider the determiner. If this is not the head then it is presumably an adjunct or a specifier within the NP. We should therefore expect it to behave as such. Determiners do not appear to be adjoined within the NP as they do not behave like adjectival modifiers, which we have analysed as N© adjuncts in the previous chapter. Adjectives are recursive modifiers of nouns and can normally be arranged in any order, as we might expect of an adjunct:

131

Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase

(11) |

NP |

|

|

NP |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N© |

|

|

N© |

|

|

||

AP |

|

|

N© |

AP |

N© |

|||

permanent |

AP |

N© |

noticeable AP |

N© |

||||

noticeable |

|

|

permanent |

|

|

|||

N |

N |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

stain |

|

|

stain |

||

Determiners, on the other hand, are not recursive and have a very fixed position at the beginning of the phrase:

(12) a |

*the this book |

cf. the book/this book |

b |

*some a property |

cf. some property/a property |

c |

*boring these lectures |

cf. these boring lectures |

Even if we claimed the determiner to be adjoined to the NP rather than the N©, so that it would always precede AP adjuncts, which are adjoined to the N©, as in (13), the nonrecursiveness of determiners would remain a problem:

(13) |

NP |

D NP

the N©

AP |

N© |

plentiful N |

PP |

supply |

of water |

A further problem with this analysis is that adjuncts adjoined to XP or X©are phrasal. Only adjuncts adjoined to a head are X0 categories. But the determiner looks suspiciously like a word and to analyse it as a phrase by itself begs the question of why determiners never have complements, specifiers or adjuncts of their own:

(14) |

|

NP |

DP |

NP |

|

? |

|

D© problematic assumption |

D |

? |

|

|

|

|

this |

|

|

132

Why the Noun is not the Head of the DP

This same problem dogs the assumption that determiners are specifiers: the specifier position is a phrasal one, but a determiner does not appear to be more than a word.

The assumption that the determiner is the head of the phrase, on the other hand, captures its position perfectly: it precedes the noun because the noun heads its complement and heads precede their complements in English. Comparing the two options, then, it seems that the one in which the determiner is the head is the more straightforward:

(15) a |

DP |

b |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D© |

|

|

NP |

||

D |

|

NP |

D? |

|

|

||

N© |

|||||||

|

|

|

troublemaker |

|

|

|

|

the |

|

the |

N |

||||

troublemaker

Another problem that arises if we assume that determiners are not heads of phrases is that they do make a contribution to the whole phrase. In chapter 1 we spent some time discussing properties of determiners (section 3.5.2), pointing out that a major contribution determiners make to the phrases that contain them is the definiteness– indefiniteness distinction:

(16)a a house b the house

The phrase in (16a) is indefinite while that in (16b) is definite, obviously as a consequence of the determiner. The noun is the same in both cases and therefore does not seem to contribute to this distinction. But if the determiner is not the head of the phrase, how does it project this property to it? Projection, we showed in the previous chapter, is a property of heads, not adjuncts or specifiers so the fact that determiners do project properties to the phrase is an argument in favour of treating them as heads.

Next, consider the status of the pronoun. If this is a determiner heading a DP, its status is quite straightforward; it is simply a head which is the solitary element in the phrase:

(17)DP D© D

her

This is nothing unusual and we find similar things elsewhere:

133

Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase

(18) |

VP |

PP |

AP |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V© |

P© |

A© |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

P |

A |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

fly |

out |

short |

|||

These phrases can be found in sentences such as:

(19)a birds [fly]

b the manager is [out]

c the trousers were [short]

Of course, if we analyse pronouns as nouns, then we get a similar situation with them heading an NP:

(20)NP N© N

they

However, the analysis in (17) accounts for the absolute complementary distribution between pronouns and determiners:

(21)a *the he b *a her

c *every they

If pronouns are determiners, this observation is accounted for. But if pronouns are nouns something else must be said to account for why they cannot appear with determiners. Some nouns do not sit well with determiners. In English, proper nouns are not usually accompanied by a determiner:

(22) a |

*a Linda left |

cf. |

Linda left |

b |

*I spoke to the Thomas |

cf. |

I spoke to Thomas |

Yet, in some circumstances we can use determiners with proper nouns:

(23)a a Linda that I used to know telephoned me yesterday b the Thomas you are thinking of is not the one I am

Interestingly, even in these situations a pronoun is ungrammatical accompanied by a determiner:

(24)a *a she/her that I used to know telephoned me yesterday b *the he/him you are thinking of is not the one I am

It seems that the evidence all points to the assumption that pronouns are determiners. But, if the noun is the head of the phrase and not the determiner, how are

134

Why the Noun is not the Head of the DP

we to analyse a phrase consisting of just a pronoun as this would appear to be an NP that lacks a noun. This brings us full circle to the observations we started with. Under the proposal that the determiner is the head, there appear to be DPs that lack determiners:

(25) |

DP |

D©

D NP

?Geoffrey

And under the proposal that nouns are the head of the phrase, there appear to be NPs that lack nouns:

(26) |

NP |

D N©

us N

?

It seems that whatever option we take we face a problem.

There is a way to solve the problem, either way, which involves a slightly more abstract analysis. Suppose the phrases in question do have heads, but they are unpronounced. The idea of an unpronounced, phonologically ‘empty’ element has been made use of several times already in this book. For example as the understood subject of an imperative or as the trace left behind by a movement. So the idea is not without precedence. Making use of this idea, we have two opposing analyses:

(27) |

DP |

|

|

DP |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D© |

|

|

D© |

|||

|

|

|

D |

|

NP |

||

|

D |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

him |

e |

|

Jackie |

|||

(28) |

|

|

NP |

|

NP |

||

|

D |

N© |

|

|

|

||

|

|

N© |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

him |

N |

|

N |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

Jackie |

||

135

Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase

Of course, the assumption of an empty category must have other motivations than just their necessity to make the analysis work. With the empty subject of an imperative we pointed out that this could act as the antecedent of a reflexive pronoun and with the trace we demonstrated how this prevents other elements from moving into a position vacated by another moved element. Is there any independent justification for either of the empty heads in (27) or (28)? If we consider the empty noun in (28), the only justification this has is to provide a head for the NP. The entire semantic content and the grammatical features of the phrase are contributed by the pronoun itself: the NP is third person singular because the pronoun is third person singular and the NP has a reference which is determined by the pronoun. Thus there is no independent support for the existence of this empty noun.

Now let us consider the empty determiner in (27). At first, we might think that we are facing the same situation here. However, this is not so. Certainly, the main semantic content of the whole phrase is provided by the noun. But this is typical: nouns are the main semantic element in such constructions, even if the determiner is visible. Determiners contribute other semantic aspects, as discussed above. The phrase Jackie is definite, as can be seen by the fact that it cannot sit in the post-verbal position in there sentences (see chapter 1 section 3.5.2 for discussion):

(29)*there arrived Jackie

This then can be taken as a reason to think that there is a determiner accompanying this noun which is responsible for the definiteness interpretation on the assumption that it is determiners and not nouns which contribute this property:

(30) |

|

DP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D© |

|

D |

|

NP |

|

|

|

|

|

[+def] |

|

Jackie |

|

This might be extended to other cases of nouns that appear without apparent determiners, as with plural nouns, for example:

(31) |

|

DP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D© |

|

D |

|

NP |

|

|

|

|

|

[–def] |

visitors from Mars |

||

Note that in this case the phrase is indefinite, as shown by the fact that it can appear in the post-verbal position of a there sentence:

(32)there arrived visitors from Mars

136

The Internal Structure of the DP

This suggests that there are two different empty determiners: one which is definite and the other indefinite. The interesting thing is that these empty determiners differ in other ways. The empty definite determiner takes only NP complements headed by proper nouns whereas the empty indefinite determiner takes only NP complements headed by plural nouns. This is perfectly normal behaviour for a head, as heads do place restrictions on their complements.

To conclude the present discussion, while it seems that there is no independent evidence that pronouns are accompanied by an empty noun, there is much evidence that proper and plural nouns may be accompanied by empty determiners. This conclusion itself lends support for the claim that the determiner is the head of the phrase and that the noun is not. From this perspective, the noun is the head of its own phrase which sits in the complement position of the determiner.

2 The Internal Structure of the DP

Having established the status of the determiner as a head, let us now look at how the DP is arranged.

2.1Determiners and Complements

We have already seen two subcategories of determiner: those which take NP complements and those which take no complement. There are also determiners which take optional NP complements:

(33) a |

the proposal |

*the |

b |

*him proposal |

him |

c |

that proposal |

that |

Determiners are rather boring in this respect and it seems that there are no other possibilities. This, as it turns out is very typical of functional categories as a whole, as they all have very limited complement taking abilities. However, even if the range of complements of the determiner is very limited, the arrangement of the determiner and its NP complement still conforms to the general pattern of head–complement relationships in English with the head preceding the complement:

(34) |

DP |

D©

D NP

As we have seen, the determiner may impose restrictions on its NP complement, particularly in terms of number: singular determiners take singular NP complements and plural determiners take plural NP complements. Some determiners take mass NP complements, and we have seen that the empty definite determiner takes a proper NP complement:

137

Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase

(35) |

singular |

plural |

mass |

proper |

|

complement |

complement |

complement |

complement |

|

a man |

*a men |

*a sand |

?a Jim |

|

*both man |

both men |

*both sand |

*both Jim |

|

some man |

some men |

some sand |

?some Jim |

|

*e[+def] man |

*e[+def] men |

*e[+def] sand |

e[+def] Jim |

|

*e[–def] man |

e[–def] men |

e[–def] sand |

*e[–def] Jim |

As heads, determiners also project their properties to the phrase and so a plural indefinite determiner will head a plural indefinite DP. We can see this from the following observations:

(36)a there are some men in the garden b there is a man in the garden

c *there is/are the man/men in the garden d the man is in the garden

e the men are in the garden

As we have pointed out, only indefinite DPs can appear in the post-verbal position in there sentences. Interestingly, in this construction the verb appears to agree with the post-verbal element. So in (36a) the post-verbal DP is indefinite, the sentence being grammatical, and the verb is in the plural form. The determiner some is an indefinite plural determiner and these properties are projected to the whole phrase. The determiner a is indefinite and singular and hence the DP that it heads can go in the post-verbal position of a there sentence and the verb will be in its singular form, as in (36b). The determiner the is definite, but unmarked for number. Therefore it cannot head a DP in the post-verbal position of a there sentence (36c), but it can trigger either singular or plural agreement on the verb when it sits in the canonical subject position, (36d) and (36e), depending on what NP it takes as a complement.

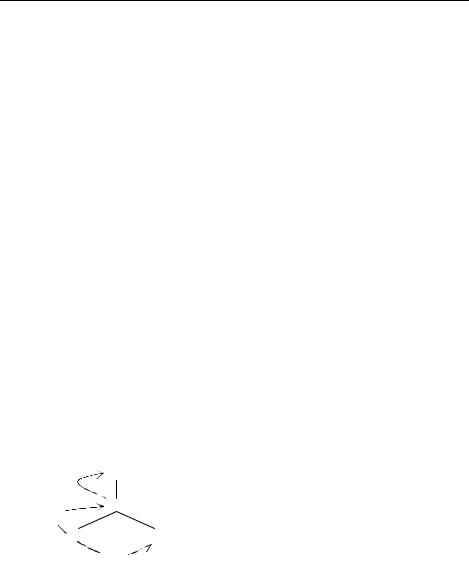

We can represent these relationships in the following way:

(37) |

DP |

D©

projects

D NP

restrict

All this is very typical of the behaviour of a head.

2.2The Specifier of the DP

Let us now turn to the specifier of the DP. Like all specifiers this should be a single phrasal element which comes before the head. The most obvious choice would be the possessor:

(38)John’s book

138

The Internal Structure of the DP

However, the problem in viewing the possessor as the specifier of the DP is that this would predict that possessors can appear in front of a determiner, when in actual fact possessors and determiners seem to be in complementary distribution:

(39)a the book

b John’s book

c *John’s the book

If X-bar theory is correct however, this observation cannot be taken to show what it seems to: i.e. that the specifier and the determiner sit in the same structural position. Words and phrases cannot be in complementary distribution as they cannot appear in the same positions in a phrase. Some other element must appear in complementary distribution with the determiner in (39c), not the possessor. But what?

To answer this question we first have to consider another property of the possessor. Pre-nominally, possessors are marked by the element ‘’s’. What is this morpheme? Some have suggested that it is the marker of genitive Case born by the possessor. However, if this is a Case marker, it is a very strange one for at least two reasons. First it is a Case marker in a language which does not usually mark Case on its nominal elements. English only normally marks Case on its pronouns and noun forms are typically invariant no matter what Case position they occupy. Yet if we take ‘’s’ to be a marker of genitive Case we have to assume that nominals are marked for this Case. The other strange thing about this morpheme seen as a marker of Case is that it does not behave anything like a Case morpheme in any other language. Note that it does not attach itself to the noun, but to the last element in the whole DP:

(40)a John’s book

b that man’s book

c the man that I told you about’s book d the man that you met’s book

This behaviour is consistent with the claim that this morpheme does not attach itself to any word, but to the whole phrase. Note this is not the way that Case morphemes behave in other languages. In Hungarian, for example, the accusative case morpheme – t is attached to the noun inside the DP, not to the last element in the DP:

(41)a egy képet Mariról b *egy kép Marirólt

There is another morpheme in English however that behaves like the possessive ‘’s’:

(42)a the man’s going

b the man that I told you about’s going c the man that you met’s going

(43)a the man’ll do it

b the man that I told you about’ll do it c the man that you met’ll do it

139

Chapter 4 - The Determiner Phrase

The contracted auxiliary attaches itself to the end of the subject in much the same way that the possessive morpheme attaches itself to the end of the possessor. The difference is, however, that with the contracted auxiliary there is an uncontracted form:

(44)a the man is going

b the man that I told you about is going c the man that you met is going

(45)a the man will do it

b the man that I told you about will do it c the man that you met will do it

Presumably, what happens when the auxiliary verb contracts is that it undergoes some process which attaches it to the subject. Very likely this is not a syntactic movement, but a phonological process which takes place after the structure has been constructed.

Evidence in favour of this comes from the comparison of auxiliary contraction and negative contraction, which does involve a syntactic movement. When the negative element not contracts, it sticks itself onto the auxiliary verb in front of it:

(46)a I will not talk b I wo-n’t talk

If the auxiliary then moves, the contracted negative is taken along. Thus when the auxiliary inverts with the subject in certain questions, the negative also inverts and cannot be left stranded behind the subject:

(47)a could1-n’t you t1 be more precise? b *could1 you t1 -n’t be more precise?

In contrast to this, a contracted auxiliary never moves along with a subject that it is attached to:

(48) a |

D-structure: |

Theodore thinks [who –’ll win] |

b |

S-structure |

*who1’ll does Theodore think [t1 win] |

Indeed, auxiliaries can contract onto a subject that has moved to the position in front of the auxiliary, suggesting that this contraction takes place after movement:

(49) a |

D-structure: |

[DP e] will seem [this man to disappear] |

b |

S-structure: |

this man1’ll seem [t1 to disappear] |

The point is, however, that there is a process which takes an independent word and sticks it to the phrase immediately in front of it. If this is what is going on with the possessive construction in English, then the ‘’s’ morpheme must originate as an independent word which sits in a position immediately following the possessor. Given that the word position immediately following the possessor is the determiner, we conclude that the morpheme ‘’s’ must be a determiner. Unlike auxiliaries, this

140