grammatical foundations

.pdf

Aspectual Auxiliary Verbs

event (the treaty being signed). It is the latter interpretation that is relevant here as this clearly involves a predication-like structure that simply lacks tense, similar to the examples in (161). Of course, the important observation is that here we have a passive construction involving a passive morpheme, but no passive auxiliary. This indicates that the function of the passive auxiliary is to bear an inflection rather than to add any semantic content.

Given the similarity between the passive construction and those constructions involving aspectual elements, it seems likely that they should receive a similar analysis. From this perspective, it is the aspectual morpheme that carries the semantic content and the associated auxiliary is merely a dummy inserted to bear another morpheme that the verb is prevented from bearing by the aspectual morpheme itself.

3.2The nature of the aspectual morpheme

Taking the similarity of the passive morpheme and aspectual morphemes one step further, we might argue that aspectual morphemes are another kind of light verb, which is not surprising as light verbs can affect the aspectual interpretation of the structure they are included in. The Urdu example given above and repeated here for convenience, uses a light verb lene ‘take’ to indicate the perfective status of the event described:

(165) nadyane saddafko xat lik lene diya

Nadya-erg. Saddaf-dat. letter write take-inf. give-perf.Masc.s ‘Nadya let Saddaf write a letter (completely)’

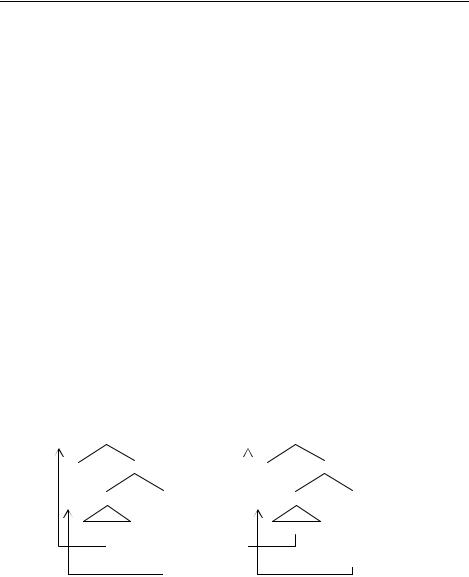

The analysis of the aspectual structure of English might therefore be as follows:

(166) a |

vP |

|

|

b |

vP |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

v© |

|

|

|

|

v© |

|

|

||

v |

|

VP |

|

|

v |

|

VP |

|

|

||

|

|

DP |

V© |

|

|

DP |

V© |

||||

ing |

en |

||||||||||

|

the door |

|

|

|

|

the door |

|

|

|||

|

V |

|

|

V |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

close |

|

|

|

|

close |

||

201

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

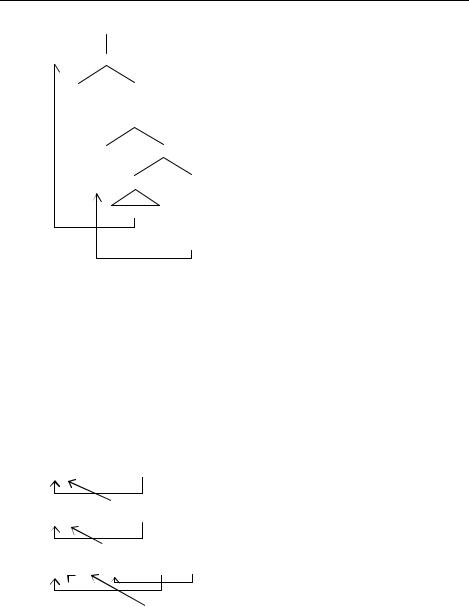

cvP v©

v |

vP |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

en |

|

v© |

|

|

||

|

v |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

||

|

ing |

|||||

|

|

the door |

|

|

||

|

|

V |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

close |

|

In all these cases, the main verb will move to support the lowest aspectual morpheme at which point it cannot move any further as its morphological structure is complete and cannot be added to. As the aspectual morphemes do not play a role in assigning - roles, they also do not have the ability to assign Case as some light verbs do. Thus, the theme will have to move to subject position to get Case.

Finally, presuming the clause to be finite, some element will have to bear the tense morpheme. As the verb cannot do this, the relevant dummy auxiliary will be inserted into the tense position: have in the presence of en and be in the presence of ing. In (167c) there is the extra complication that there are two aspectual morphemes as well as the tense morpheme. In this case the verb moves to the lowest aspectual morpheme, ing, and an inserted auxiliary will bear the other morphemes, be for the perfective and have for the tense:

(167) a - ed [en [the door close]]

= the door1 had [closed2 [t1 t2]] have

= the door1 had [closed2 [t1 t2]] have

b - ed [ing [the door close]]

= the door1 was [closing2 [t1 t2]] be

= the door1 was [closing2 [t1 t2]] be

c - ed [en [ing [the door close]]]

= the door1 had [been [closing2 [t1 t2]]

have be

With these assumptions then we can successfully account for the distribution of the aspectual elements in the English clause. We will provide more detail of the upper part of the clause structure including the tense and clausal subject position in the next chapter.

202

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers

4 Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers

To complete this chapter, we will briefly mention modification in the VP. Modifiers may generally be associated with adjuncts and so the modifiers of the VP can be assumed to be adjoined somewhere within the VP structure we have introduced above. There are restrictions however, which partly depend on general conditions and partly depend on the nature of the modifier itself. We will briefly look at each type of modifier in turn.

4.1Adverbs

Adverbs are the classic verbal modifiers. We should be careful, however, to distinguish between them, as some do not modify within the verbal domain of the clause, but have a wider domain of operation, modifying clausal elements. Roughly we can separate VP adverbs from sentential adverbs. Consider the following examples:

(168)a he certainly will find out b he will quickly find out

The adverb in (168a) modifies the meaning of the whole clause: what is certain is that he will find out. In contrast, the adverb in (168b) modifies the verb, stating that it will be done in a certain manner (i.e. quickly). Note the different positions of these two adverbs: the sentential adverb precedes the modal auxiliary while the VP adverb follows it and is therefore closer to the VP. Indeed, placing the VP adverb further from the VP often produces an ungrammaticality:

(169)a *he quickly will find out

b *she suddenly has realised her mistake

c *the doctor thoroughly may examine the patient

These sentences can be made more acceptable if heavy stress is placed on the finite element, but with neutral stress they are ungrammatical, indicating that something special has to happen to get the adverb away from the VP it modifies.

It seems a reasonable conclusion therefore that VP adverbs are adjoined to the VP itself. But the VP is a fairly complex structure, as we have seen. Where in the VP can the adverb adjoin? Consider the possible range of positions we can find the adverb in:

(170)a will accurately have been making notes b will have accurately been making notes c will have been accurately making notes d *will have been making accurately notes e will have been making notes accurately

There looks to be a good deal of freedom in determining the position of the adverb and thus it appears to be able to adjoin to virtually any part of the VP. The one exception is that the adverb may not intervene between the verb and its object. However, the adjacency requirement between the verb and its object is not so straightforward to account for under the assumptions we have been making. Other accounts of this restriction have made different assumptions. For example, Radford (1988) assumes that the object is in the complement position of the verb and that the adjacency

203

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

requirement between the two is a reflex of X-bar theory itself: the head must be adjacent to its complement otherwise an ill formed structure results:

(171)XP X©

X©

X adjunct complement

If an adjunct is placed between the head and its sister, i.e. the complement, the branches of the structure cross and this is not a possible configuration. The problem with this account, however, besides its reliance on the assumption that complements are all sisters to the head, is that it is not at all clear why various movement phenomena would not separate the head from its complement. Another account, due to Stowell (1981) assumes that the verb is responsible for assigning Case to the object and that there is an adjacency requirement on Case assigners and assignees. As we have assumed that the theme gets its Case from the light verb, we cannot use Case adjacency to account for why the verb and its theme argument cannot be separated. Even if we assume that Case assigners must be adjacent to the element they Case mark, this will not prevent the verb moving to a higher light verb position allowing an adverb to come between the two:

(172)vP

DP v©

v vP

AP vP

v©

v VP

DP V©

V

This structure has the adverb phrase adjoined to the lower vP and the verb moving to the higher light verb. Such a structure would be possible either when there is both an agent and an experiencer argument, or if the top light verb is an aspectual morpheme. The structure that would be produced however would be ungrammatical as the adverb would appear between the verb and its theme argument.

We might try to account for this restriction by limiting the kinds of structure that the adverb can adjoin to. But this seems unlikely as under certain conditions adverbs appear to be able to adjoin to virtually any part of the VP:

204

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers

(173)a the letter1 might [VP eventually [VP t1 arrive]]

b Peter2 might [vP suddenly [vP t2 punch1-v [VP Paul t1]]]

c water2 is [vP steadily [vP pour1-ing [VP t2 t1 out of the bath]]]

d Betty2 has [vP annoyingly [vP beat1-en [vP t2 t1 [VP me t1 again]]]]

In (173a), given that there is no light verb with an unaccusative verb, the adverb must be adjoined to the VP. In (173b) the adverb is adjoined to a vP headed by an agentive light verb and in (173c) and (d) it is adjoined to a vP headed by aspectual morphemes. Thus there seems to be no limit in principle on what the adverb can adjoin to. In each of these cases however, the adverb is adjoined to a higher position than the verb moves to. When there is no light verb, as in (173a), the verb is not forced to move out of the VP and in this case the adverb can adjoin to the VP. If the verb moves out of the VP, however, the adverb cannot adjoin to it. Indeed, anything that the verb moves out of is out of bounds for an adjunction site for the adverb. This suggests that the adverb interacts with the movement of the verb and it is this interaction that determines the possible adjunction sites for the adverb. Specifically, it seems that the verb never moves over the top of the adverb. Hence, we may assume that in principle an adverb can adjoin to any part of the extended VP, including any light verb projection, as long as the verb remains lower than it at S-structure and does not move over its adjunction position. There are a number of ways in which we might attempt to account for this fact, but at present we will be satisfied at leaving it as a descriptive generalisation.

Another observation that can be made from the data in (170) is that adverbs may appear behind all verbal elements. There are a number of possible ways to capture this fact. One is to assume that adjunction is free from ordering restrictions. Indeed it does seem that different adjuncts can come on different sides of whatever they modify: the PP modifier, as we shall see, typically follows the verbal complex. Thus, adjunction in general is not restricted to a particular side as are complements and specifiers. Adverbs therefore may simply take advantage of this freedom and be adjoined either to the left or the right of the VP. The alternative would be to have adverbs generated on one side of the VP and then achieve the other position via a movement. Jackendoff (1977), for example, argued for this position on the basis of the similarity between adverbs and adjectives. Recall that in chapter 1 we analysed adverbs and adjectives as belonging to the same general category, so one might expect grammatical principles to apply to both in a similar way. Jackendoff’s observation was that adjectives typically precede the nouns that they modify:

(174) a |

stupid fool |

*fool stupid |

b |

heavy book |

*book heavy |

c |

precocious child |

*child precocious |

If we assume therefore that the basic position of the adjective is before the noun that it modifies, we might take this to indicate that the basic position of the adverb is before the verb that it modifies and therefore that its post-verbal position is a derived one. We are not really in much of a position to be able to evaluate either of these positions and therefore we will leave the matter unresolved.

205

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

4.2PP modifiers

The other main modifier in the VP is the PP. This differs from the AP modifier in its distribution in that it always follows the verb. Thus a PP modifier has a far more restricted distribution than an adverbial one:

(175)a *may in the lake have been swimming b *may have in the lake been swimming c *may have been in the lake swimming d may have been swimming in the lake

Understandably, we cannot get a PP modifier between a verb and its complement, just like Adverbs, however we can separate a verb from its PP complements:

(176)a *flowed under the bridge the river b live with his mother in Paris

The only way for (176a) to have been generated would be to adjoin the PP to the left of the lower VP. However, PPs never adjoin to the left, only to the right, and moreover this would necessitate the verb moving over the PP adjunct. As this is impossible for AP modifiers, we can assume that it is impossible for PP modifiers as well. In (176b), assuming the locative PP to be the complement of the verb, the only way for this to get behind the PP adjunct would be for it to move. And hence we can assume that there is a backwards movement that PP arguments may undergo which is similar to the movement that clausal complements undergo, as discussed in section 3.8. That PP complements may undergo such a movement is supported by the following data:

(177)a a book about penguins was published last week b a book was published last week about penguins

In this example, the PP is part of the subject DP and yet it may appear on the opposite side of the clause to the subject, indicating that it can undergo this kind of movement.

DP complements, however, cannot move backwards past a PP adjunct as can be seen by (176a). We might assume that this is because the DP must occupy a Case position and hence cannot move away from its specifier position in the VP. However, this is not so straightforward as DPs can be moved out of Case positions in some instances and moreover some DPs can undergo backward movement:

(178)a this exercise1, I don’t think anyone can [do t1] b which book1 were you [reading t1]

c you should complete t1 in ink [every form with a blue cross at the top]1

In (178a) and (b) the object has undergone a movement to the front of the clause, out of its Case position. But if this is an allowable movement, why should it not be allowed to move to the back of the clause? In (178c) the object has moved backwards behind the PP adjunct with ink. In this case, the DP is very long and complex involving quantification and post head modification. A simpler DP would not be allowed to do the same thing:

(179)*you should complete t1 in ink [the form]1

206

Adverbs, PPs and Clausal modifiers

We can call the phenomena noted in (178c) heavy DP shift (leaving undefined just what counts as a ‘heavy DP’). It is common to find the attitude that heavy DP shift is a slightly odd phenomenon. However, given that other elements can undergo backward movement and given the fact that DPs of any weight can undergo certain forward movements, what is odd is the refusal of ‘light’ DPs to undergo backward movement. Obviously there are mysteries here that we cannot yet approach and so again we will set the issue aside.

4.3Clausal modifiers

Finally in this chapter we will note the possibility of modifying a VP with a clause. As we have seen with adverb modifiers the most straightforward VP modifiers are those that modify the manner of the verb. It is not possible to use a clause in this way however, and so it is not easy to tell whether a clause is a VP or a sentential modifier. However, there are certain reasons to think that some clausal modifiers are situated inside the VP.

Without going too much into the details of clause structure itself, a task we will undertake over the next chapters, certain non-finite clauses appear to have a missing subject:

(180)a Bert bought a Ferrari [to impress his friends]

b they set fire to the building [to collect the insurance]

Although these clauses seem to lack a subject, it is immediately obvious that a subject is interpreted: in (180a) it is Bert who will be doing the impressing and in (180b) it is they who will collect the insurance. We call this phenomenon control. There is an element in the main clause who is interpreted as, or who ‘controls’ the missing subject of the modifying clause. There are restrictions, however, on which argument can act as the controller:

(181)Fred phoned the plumber [driving to the office]

In this case, only Fred can be interpreted as the one who was driving. It seems that the object is too far down inside the clause to act as controller. This is supported by the following observation:

(182)the witness claimed the defendant paid a lot of money [to attract attention to himself]

The reflexive pronoun himself can either refer to the witness or the defendant. But note, this depends on what the purpose clause is thought to modify. In one case it is the defendant’s paying money that attracts the attention and in the other case it is the witness’s claim that attracts the attention. In the first case, himself refers to the defendant and in the second it refers to the witness. What is not possible is to interpret the purpose clause as modifying the claiming event and for the reflexive to refer to the defendant or for the purpose clause to modify the paying event and the reflexive to refer to the witness. In other words, neither of the following are possible interpretations of (182):

207

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

(183)a the purpose of the witnesses claim that the defendant paid a lot of money was to attract attention to the defendant

bthe witness claimed the purpose of the defendant paying a lot of money was to attract attention to the witness

We can account for this in the following way. We know from chapter 3 that reflexive pronouns must refer to something within their own clause and in (182) the only thing that could be the referent of the reflexive is the missing subject. The missing subject is in turn controlled by some other element in the clause and hence limitations on the reference of the reflexive indicate limitations on the control of the subject. When the purpose clause modifies the higher verb, only the subject of this verb can act as the controller and hence be the ultimate referent of the reflexive. It seems that the subject of the other clause is ‘too low down’ in the clause to act as controller. On the other hand, this subject can act as controller when the purpose clause modifies the lower verb.

Having established that there are structural conditions on what can act as a controller, consider the following examples:

(184)a Harry hired Freda [to fire the security guard] b Harry fired Freda [to hire the security guard]

(184a) is ambiguous in terms of who is doing the firing: it could be Harry or Freda. (184b) is not ambiguous however as here only Harry can do the hiring. What can account for this difference? We have seen that the structural position of the purpose clause affects what can be the controller and so it might be that there are different possible positions for the purpose clause within the structure. The structure of the main VP in (184a) is as follows:

(185)vP

DP v©

Harry v |

|

VP |

e |

DP |

V© |

Freda V

hire

As agent, Harry is the specifier of an agentive light verb and as theme Freda is the specifier of the main verb. The verb will move to support the light verb as usual. We know in this case, the purpose clause can either be controlled by the subject or the object and so it must be able to attach to the structure high enough to allow subject control and low enough to allow object control. Suppose we assume that the purpose clause can adjoin either to the v©or to the V©:

208

Conclusion

(186) a |

vP |

|

|

|

DP |

|

v© |

||

Harry |

v© |

|

S |

|

v |

VP |

|

to fire the security guard |

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

|

e |

||||

|

|

Freda |

|

|

|

|

V |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hire |

|

b vP

DP v©

Harry v |

VP |

|

e |

DP |

V© |

|

Freda V© |

S |

V to fire the security guard

hire

The two structures relate to the two possible meanings. When the purpose clause is adjoined to the v©, as in (186a), then the agent can control the missing subject, and when it is adjoined to the V©, as in (186b), then the theme can control the missing subject. For some reason, when fire is the head of the VP, the purpose clause can only be adjoined to the v©and hence only the agent can be the controller. Hence there will be no ambiguity. Note that the facts as such demonstrate that the purpose clauses must be able to attach within the VP so that objects can act as controllers. If this were never the case, we would only be able to get subject control.

5 Conclusion

In this chapter we have taken a detailed look into various aspects of the structure of the VP. We have seen how the semantics of the verb, particularly in its argument and event structures, influence the way the VP is built. The argument structure to a large extent determines the complementation of the verb and the event structure plays a role in determining the extension of the VP into various vPs built on top of it.

In numerous places we have mentioned the sentence, which the VP is a major part, but have so far refrained from discussing, using the symbol ‘S’ to stand instead of a proper analysis. One important aspect of clausal structure for the VP is the position of

209

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

the subject, which as we have maintained throughout this chapter starts off inside the VP, but moves to the nominative position somewhere higher in the clause. We will consider issues such as this in the following two chapters when we discuss clause structure in more detail.

Check Questions

1Explain the notions ‘event structure’ and ‘aspect’.

2Compare unaccusatives with ergative and intransitive verbs. Consider the event structure of the verbs, their complementation, the position and theta roles assigned to the complements, the ability to appear in causative and/or passive contexts, diagnostics for telling them apart, and further properties.

3Consider the specifier position in a projection headed by a light verb and a thematic verb. How can it be argued that the two specifier positions are assigned different theta roles?

4What evidence is available to support the assumption that there is an empty light verb in the transitive counterpart of a light verb+unaccusative verb structure?

5How is passive conceptualised in the text?

6What assumption(s) provides a way out of the problem(s) that both agent and experiencer arguments occupy [Spec, vP] at D-Structure? What other evidence is available to support the existence of multiple light verb constructions?

7What is the analysis proposed for multiple complement constructions developed in the text?

8What arguments are put forward against the assumption that clausal complements occupy the [Spec, VP] position?

9On the basis of the text make a list of verb-types identified.

Test your knowledge

Exercise 1

Identify instances of a semantically contentless ‘there’ and ‘it’ in the sentences below.

(1)a There was a man at the door.

bHe put the book there.

cThe apples are there.

dThere is no reason to fight.

eIt took them two hours to get there.

fIt appears to be out of order.

gIt appears that he got lost.

hI take it that the answer is ‘no’.

iThere are no policemen there.

jHe had a hard time of it in the army.

210