grammatical foundations

.pdf

Testing for Structure

(103) a |

where did they find the gun |

(A = under the bishops mitre) |

b |

how did the judge find the bishop |

(A= guilty!) |

The fact that the answer to (103a) is a preposition phrase and that to (103b) is an adjective phrase is an indication that these wh-elements are prepositional and adjectival respectively.

Not every kind of phrase can be questioned in this way, however. For example, there is no wh-element that corresponds to a VP, nor one for an NP. However the fact remains that only constituents can undergo this movement and so it can act as a fairly reliable test for the constituent structure of most parts of a sentence.

It is important to note that only one constituent can undergo any particular movement and that two constituents cannot move together. To demonstrate this, consider the following sentence:

(104)the bishop killed the bank manager with the gun

This sentence can be interpreted in one of two ways depending on who is seen as having the gun. If it is the bank manager who has the gun, then the PP with the gun acts as a modifier within the DP the bank manager with the gun. If, on the other hand, the bishop has the gun, then the PP is interpreted as modifying the VP killed the bank manager with the gun. In the first interpretation the PP is a kind of locative modifier, locating the gun with the bank manager and in the second it is an instrumental modifier saying what was used to kill the bank manager. The important point to note is that in the first case the PP forms a single constituent with the DP, whereas in the second it is a separate constituent from this. Thus we have the two structures:

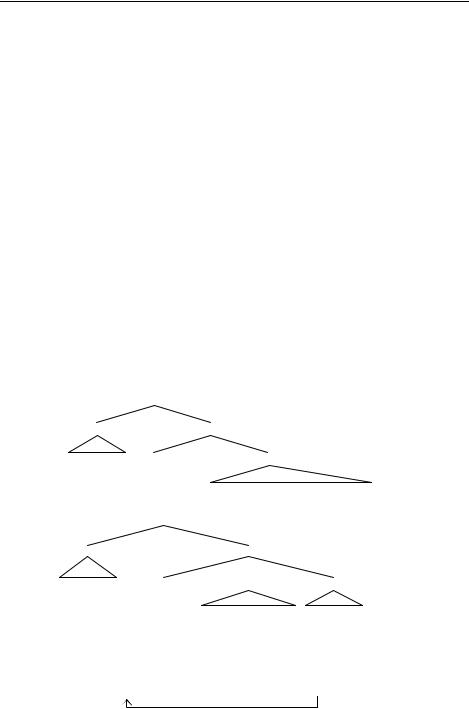

(105) a |

S |

|

|

|

||

DP |

|

|

|

VP |

|

|

the bishop |

V |

|

|

DP |

||

|

|

|

|

the bank manager with the gun |

||

|

killed |

|||||

b |

|

S |

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

|

VP |

|

|

the bishop |

|

V |

|

|

PP |

|

|

DP |

|||||

|

|

|

the bank manager with the gun |

|||

|

killed |

|||||

Suppose we topicalise the object in (105a), moving the DP to the front of the clause. As the PP is part of the DP it will be carried along with the rest of it and we will derive the following sentence:

(106)the bank manager with the gun, the bishop killed –

81

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

This sentence is no longer ambiguous between the two meanings. This is because we must interpret the moved element as a single constituent and not as two separate constituents that have been moved together. The same point can be made with the movement of wh-elements, as shown by the following:

(107)which bank manager with a gun did the bishop kill –

Again this sentence is unambiguous and the PP must be interpreted as modifying the DP and not the VP. An overall conclusion about movement is therefore that anything that can be moved is a single constituent and hence movement provides a relatively robust and useful test for constituent structure.

3.3Coordination

There are other phenomena besides distribution that can also be used to support structural analyses. One of these involves coordination. This is a device used in language to take two elements and put them together to form a single element. This coordinated element then acts like the two coordinated elements would have individually. For example, we can take two nouns, say Bill and Ben, and we can coordinate them into a single element Bill and Ben. This coordinated element behaves exactly like each of the nouns in that it can appear as subject, object, object of a preposition or topic in a sentence:

(108)a Bill and Ben went down the pub b I know Bill and Ben

c they sent a letter to Bill and Ben d Bill and Ben, everyone avoids

The point is that as the coordinated element behaves in the same way as its coordinated parts would individually, we cannot coordinate two conflicting things. So while two nouns can be coordinated, and two verbs can be coordinated, a noun and a verb cannot:

(109)a the [boys and girls]

b have [sung and danced]

c *the [boys and danced] have [sung and girls]

Not just words can be coordinated however; we can also coordinate phrases and sentences. As long as the phrases and sentences are sufficiently the same, the result will be a phrase or a sentence which behaves in the same way as its coordinated parts:

(110)a [these boys] and [those girls]

b [have sung] and [are now dancing]

c [the boys have sung] and [the girls are now dancing]

Just like in the case of movement, only constituents may be coordinated and two independent constituents cannot act as one single conjunction which is coordinated with another. To demonstrate this, recall the ambiguous sentence in (104) where the PP was either associated with the object DP or with the VP. Now, if we coordinate the

82

Testing for Structure

string of words, the bank manager with the gun with the DP the security guard, the ambiguity is resolved:

(111)the bishop killed the bank manager with the gun and the security guard

In this example two DP objects are coordinated, one the bank manager with the gun and the other the security guard. The first conjunct cannot be interpreted as a separate DP with following PP modifying the VP as this would not constitute a single constituent which could be coordinated with the second DP.

Again we can turn these observations round to provide a test for structural analyses. If we claim that a certain part of a sentence constitutes a phrase, then to test this claim we could take another similar element and see if the two things can be coordinated. Thus, to go back to the structure proposed in (100), there are three constituents proposed: the subject DP, the VP and the object DP inside the VP. If this is accurate, we should be able to find an element to coordinate with these constituents to form grammatical sentences:

(112)a [[the policeman] and [the chief constable]] searched the bishop

b the policeman [[searched the bishop] and [confiscated his crosier]] c the policeman searched [[the bishop] and [the verger]]

The prediction seems to be supported and hence we can feel reasonably confident about the structure proposed in (100).

The coordination test, however, needs to be carefully applied. Recall that the way coordination works is to take two elements and form them into a single element that has the same function as the two elements would have individually. It therefore follows that two elements cannot be coordinated if they do not have the same function, even though they may be constituents of the same category. For example, if we tried to coordinate a PP that was a locative modifier of a DP with one which was an instrumental modifier of a VP the result would be ungrammatical:

(113)*the bishop shot the bank manager with a moustache and with a gun

By the same token, two constituents with the same function can be coordinated, even if they do not have the same categorial status:

(114)you should take the medicine regularly and under proper medical supervision

In this example the adverb regularly and the PP under medical supervision have the same modifying function in the VP and hence can be coordinated.

Still, despite these few complications, it remains a fact that only constituents can be coordinated and hence the coordination test is also a fairly reliable one for constituent structure.

3.4Single-word phrases

There is an important point we should make before finishing this chapter. We have claimed that elements which have the same distribution have the same categorial status. We have also seen cases where phrases can be replaced by a single word. This leads us to the conclusion that these words have the status of the phrases they replace.

83

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

This might sound contradictory, but it is not. The fact is that phrases can consist of one or more words. Thus, while smile is a verb, it is also a VP in the following sentence:

(115)the Cheshire cat [VP smiled]

Furthermore, while a pronoun is a determiner, it is also a DP in the following sentence:

(116)I never knew [DP that]

We have also seen that the word there can replace prepositional phrases, and so not only is it a word, it is also a PP:

(117)we don’t go [PP there]

The situation is easy enough to represent in terms of a tree diagram:

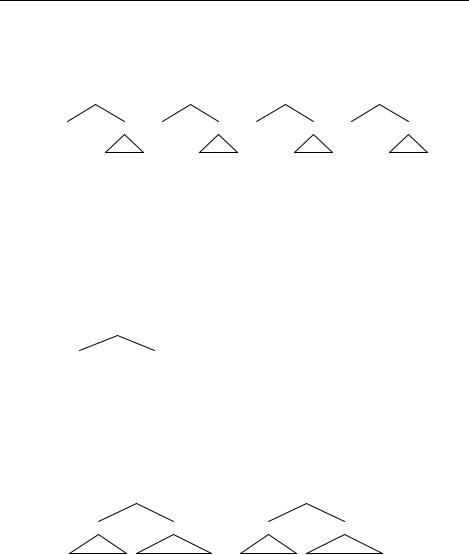

(118) a VP |

b DP |

c PP |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

D |

P |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

smiled |

that |

there |

|||

In such trees the dual status of these elements as both word and phrasal categories is clearly represented.

Check Questions

1What are phrases?

2What are rewrite rules?

3Define what a recursive rule looks like and comment on its importance in the grammar.

4Compare characteristics of subjects in finite and non-finite clauses.

5What is an direct object, an indirect object and a prepositional object?

6Compare the dative construction with the double-object construction.

7What tests can you use to define whether a string of words forms a constituent

or not?

84

Test your knowledge

Test your knowledge

Exercise 1

List the rewrite rules used in generating the following structure:

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

VP |

|

|

|

The |

NP |

was |

|

VP |

|

|

bishop |

S |

|

hiding |

|

|

PP |

|

DP |

|||||

|

that just left |

|

|

a gun |

under DP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

his mitre |

Exercise 2

Identify the constituents in the following sentences.

aThe postman lost his key yesterday.

bThe student who has just passed the exam is very happy.

cThis theory of language acquisiton is easy for students who understand mathematics.

Exercise 3

Account for why the following sentences are ungrammatical.

a*Yesterday I met Paul and with Peter.

b*Whose did you see favourite film?

c*Mike invited the woman with long hair, Jamie invited the she with short hair.

d*The student, I haven©t seen of Physiscs lately.

e*She can paint with her mouth and with pleasure.

85

Chapter 3

Basic Concepts of Syntactic

Theory

1 X-bar Theory

1.1Rewrite rules and some terminology

We will start by looking at some general principles that determine the basic structure of phrases and sentences. The perspective we will present claims that these principles are simple because there are a very small number of them that apply to all structures. In fact this theory claims there to be at most three different rules which determine the nature of all structures in a language. These can be stated as follows:

(1)a X©→ X YP

b XP → YP X© c Xn → Xn, Y/YP

Recall from chapter 2, rewrite rules which tell us how structures of various kinds decompose into their constituent parts. The rules in (1) are like these, only far more general. The generality is achieved through the use of category variables, X and Y, which stand for any possible category (nouns, verbs, prepositions, determiners, etc.). Thus these rules tell us how phrases in general are structured, not how particular VPs, PPs or DPs are.

The third rule in (1) introduces a position into the phrase called the adjunct. Given that we have yet to introduce these elements we will put off discussion of this rule until section 1.3. where we will give a fuller account of both adjuncts and the adjunction rule.

The first rule (1a) is called the complement rule, as it introduces the structural position for the complement (the YP of this rule). The structure it defines is given below:

(2) |

X© |

X YP

There are several things to note about this structure. First there are two immediate constituents of the X©(pronounced “X bar”): X, which is called the head of the phrase and the complement YP. The complement, which, as its label suggests is a phrase of any possible category, follows the head. This is a fact about English and in other languages the complement may precede the head.

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

Whether it precedes or follows the complement, the head is the central element of the phrase and is a word of the same category as the X©. Thus, if the head is an adjective, the X©will be an A©and if the head is a complementiser the X©will be a C©.

Here are some structures that conform to this pattern:

(3) |

|

V© |

|

|

N© |

|

|

P© |

D© |

|

V |

PP |

N |

PP |

P |

DP D |

NP |

||||

|

|

to me |

|

|

of Spain |

|

|

|

|

shame of it |

speak |

king |

on |

the right the |

|||||||

Note that, although these are constituents of different types, they all have a very similar pattern: the head is on the left and the complement is on the right. This is exactly what the X-bar rules were proposed to account for. It is clearly the case that there are cross-categorial generalisations to be made and if constituents were described by the rewrite rules of the kind given in chapter 2, where for each type of constituent there is a specific rule, it would be impossible to capture obvious similarities between phrases.

The rule in (1b) is the specifier rule, as it introduces a structural position called the specifier (the YP of this rule). The structure it defines is as below:

(4) |

XP |

YP X©

Again there are several things to note about this structure. Once more, there are two immediate constituents of the phrase. The specifier, a phrase of any category, precedes the X©, the constituent just discussed containing the head and the complement. Again the ordering of these two constituents is language dependent: specifiers precede X©s in English, but this is not necessarily so in all languages. Specifiers are a little more difficult to exemplify than complements due to complications that we have yet to discuss. However, the following are fairly straightforward cases:

(5) |

DP |

VP |

|

DP |

D© |

DP |

V© |

the king’s |

every wish |

the bubbles |

rise to the surface |

The specifier of the DP is the possessor and this precedes the D©constituted of the determiner and its complement. The VP in (5) is exemplified in the following sentence:

(6)we watched [the bubbles rise to the surface]

This VP has many things in common with a clause and indeed it looks very much like one. We will discuss the difference between the two in a subsequent chapter. The important point to note is that the theme argument of the verb (the argument undergoing the process described by the verb – in this case, the bubbles) occupies the specifier position of the VP as defined by the rule in (1b).

88

X-bar Theory

Note that the X©and the phrase share the same categorial status (X) and so if X©is P©XP will be PP, etc. As X©is the same category as the head, it follows that the whole phrase will be of the same category as the head. In this way, the head of the phrase determines the phrase’s category.

The property of sharing category between the head, the X©and the phrase is called projection. We say that the head projects its categorial status to the X©and ultimately to the XP. If we put the two parts of the structure together, we can more clearly see how projection works:

(7) |

VP |

|

DP |

|

V© |

the children |

V |

PP |

fall over

The line of projection proceeds from the head, via the X©to the phrase thus ensuring that phrases and heads match.

The meaning of the ‘bar’ can be seen in terms of the notion of projection. We can imagine a phrase as a three-floored building, with a ground floor, a first floor and a top floor. On the ground floor we have the head, which is not built on top of anything – it is an unprojected element. Often heads are called zero level projections, to indicate that they are not projected from anything. This can be represented as X0.

Above the head, we have the X©, the first projection of the head. The bar then indicates the projection level of the constituent: X©is one projection level above X0.

On the top floor we have the phrase, XP. This is the highest level projected from the head and hence it is called the maximal projection. Another way of representing the maximal projection is X©, an X with two bars (pronounced ‘X double bar’), with the bars again representing the projection level. It seems that all phrases project to two levels and so we will not entertain the possibility of X ©, or X ©, etc. Typically we will maintain the custom of representing the maximal projection as XP.

1.2Endocentricity

An obvious consequence of the notion of projection is that we will never get a phrase of one category with a head of another. While this might seem a slightly perverse situation to want to prevent in the first place (why would verb phrases be headed by anything other than a verb?), it is certainly a logical possibility that there could be phrases of category X which do not contain a word of category X. For example the traditional view that preposition phrases can function adverbially could be captured under the following assumption:

(8)AP → P DP

In other words, a preposition phrase which behaves as an adverbial phrase is an adverb phrase headed by the preposition. Clearly this is something that would not be allowed by the X-bar rules in (1). Evidence favours the X-bar perspective and there is no reason to believe that just because something functions adverbially it is categorially the

89

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

same as an adverb. For example, even when PPs are used adverbially, they still have different distributions to AP:

(9)a we met [AP secretly] b we [AP secretly] met

we met [PP in secret] *we [PP in secret] met

As we see in (9), a PP modifier of a verb must follow it, while an AP modifier may precede or follow it, even if the two modifiers have virtually the same interpretation. Thus a phrase headed by a preposition has a different categorial status to one headed by an adverb, supporting the X-bar claim that phrases have heads of the appropriate kind.

Moreover, the X-bar rules in (1) rule out another possibility if we assume that these are the only rules determining structure. While it might not make much sense to have a phrase with a head of a different category, the idea of a phrase that simply lacks a head is not so absurd. There is a traditional distinction made between endocentric and exocentric language elements. An endocentric phrase gets its properties from an element that it contains and hence this element can function by itself as the whole phrase. For example:

(10)a I saw [three blind mice] b I saw [mice]

An exocentric phrase on the other hand contains no element that can have the same function as the whole phrase and so appears to have properties that are independent from the elements it contains. A standard example is:

(11)a we saw him [in the park] b *we saw him [in]

c *we saw him [the park]

The issue is rather complex. The traditional view mixes category and function in a way that is perhaps not helpful. The point is, however, that the X-bar rules in (1) claim that, categorially, all phrases are endocentric: in other words, all phrases have heads which determine their categorial nature.

There is one grammatical construction that seems at first to stand outside the X-bar system precisely in that it lacks a head: the clause. Certainly from a functional perspective the clause contains no element that could replace the whole construction: neither the subject nor the VP can function as clauses by themselves:

(12)a [Susan] [shot Sam] b [Susan]

c [shot Sam]

The examples in (12) all have very different natures, even categorially. It might be argued that sometimes VPs can act as clauses:

(13)get out!

However, such expressions have a special status and there is more to them than appears at the surface. The sentence in (13) is an imperative construction in which there appears to be no subject. However it is fairly clear that there is a definite subject

90