grammatical foundations

.pdf

Theoretical Aspects of Movement

morphological Case distinctions? There are two things that we might say. One is that Case positions are only Case positions when occupied by a pronominal DP. This would be rather difficult to arrange however, as it appears that apart from the fact that Cases are only visible on pronominals, what defines Case positions is fairly general: the subject of a finite clause is nominative, the object position of a verb or preposition is accusative and the subject position of a non-finite clause is accusative. It is not clear how to include the presence of the pronominal into the definition of a case position.

The alternative is to claim that there are general case positions that are occupied by any DP, but only some DPs show any morphological reflex of this. Obviously this is the more general and simplest position and hence it is preferable unless there can be demonstrated to be advantages of accepting that case positions are only defined in the presence of a pronoun.

One reason to believe that case positions are generally defined but just morphologically distinguished on certain elements is the fact that case is not distinguished on all English pronouns. For example there is no distinction between nominative and accusative for the pronoun it:

(86)a he eats it b it eats him

The third person singular masculine pronoun demonstrates a Case distinction between subject and object position in (86), but not the pronoun it. It would be extremely difficult to account for why Case positions are only defined in the presence of pronouns, except for it and would be much better to say that the Case position is defined in the presence of it but this pronoun does not realise the distinction overtly. In other words, it is the nominative form of this pronoun and it is the accusative form. But once we have accepted this as a possibility it is reasonable to accept it for all other nominal elements as well.

One way to view this situation is to separate two notions of Case. One notion of Case, relating to the traditional view, is that Case has to do with the form a nominal element takes dependent on its position or, in some languages, its function in a sentence. We can call this phenomenon Morphological case. The other view of Case is that this is something a DP gets simply by occupying a certain structural position, whether or not it is realised overtly. We call this Abstract Case, or just Case (spelled with a capital). From this perspective then, any DP that occupies the subject position of a finite clause has nominative Case irrespective of whether that DP looks different from what it would if it were sitting in an object position and bearing accusative Case.

One piece of support for this distinction comes from observations such as the following:

(87)a for her to be ready on time would be a miracle b *for she to be ready on time would be a miracle c *her to be ready on time would be a miracle

d *she to be ready on time would be a miracle

In (87) we have a series of pronominal subjects of non-finite clauses. In the one grammatical case the subject is accusative, demonstrating that this is an accusative position. The ungrammaticality of the nominative pronoun in (87b) is therefore

111

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

understandable. That (87c) should be ungrammatical is interesting as here we have an accusative pronoun. In this case the complementiser for is absent, indicating that this element is in some way responsible for the accusative case in (87a) in which it is present. This is understandable as this complementiser is similar to a preposition, and in fact is often called the prepositional complementiser, and as we know, the complement of prepositions is in the accusative. To account for this let us assume that Case is rather like -roles and is assigned by certain elements to certain positions. The prepositional complementiser therefore assigns accusative Case to the subject of the non-finite clause that it introduces:

acc

(88)[CP for [IP her to be ready …

Although this might explain why the subject has accusative Case in (87a) and cannot have nominative Case in (87b), by itself it does not account for why (87c) and

(d) are ungrammatical. To understand what is going on here we must attend more closely to the facts. Firstly the element that we have assumed to assign accusative Case to this position is absent and so we might assume that no accusative Case is assigned in these circumstances. Presumably whatever it is that assigns nominative Case is not present in a non-finite clause. Therefore in this situation it seems that neither accusative nor nominative case are assigned to the subject position.

But why would any of this mean that the sentence should be ungrammatical? Only with an extra assumption can we account for this properly: the pronoun subject needs a Case. One might think that this is fairly obvious as there is no Case neutral form of the pronoun: what form would it take if it occupied a Caseless position? However, the following observations seriously question the assumption that the ungrammaticalities in (87) have anything to do with Morphological case:

(89)a for Rebecca to be ready on time would be a miracle b *Rebecca to be ready on time would be a miracle

What we see here is that even a nominal element that does not display morphological case distinctions cannot occupy a position to which no Case is assigned. Thus the requirement that a nominal element have Case is nothing to do with the impossibility of the choice of morphological form when no Case is assigned. Instead, it appears to be a general requirement that all DPs must occupy a Case position. We call this requirement the Case Filter:

(90)the Case Filter

All DPs must be assigned Case

The fact that the Case Filter applies to all DPs and not just those that demonstrate morphological case is strong evidence in favour of the assumption of Abstract Case.

Let us review what we have said so far. We started with the observation that the position that a DP occupies at S-structure determines its Case. We then claimed that Case is something applicable to all DPs and finally we proposed a general condition to the effect that all DPs must receive Case. But putting all this together it is obvious that the Case Filter can only operate at S-structure as, as we have seen, D-structure positions are in general irrelevant for determining the Case of an element. Consider the

112

Theoretical Aspects of Movement

possibility that all the grammatical principles involved with Case and its assignment are bundled together in a single Case theory, paralleling Theta Theory discussed above. Case theory then applies to S-structure:

(91) |

Lexicon |

|

X-bar theory |

D-structure  Theta theory

Theta theory

movement

S-structure  Case theory

Case theory

While Theta theory accounts for the distribution of arguments at D-structure, it is the principles of Case theory that account for the distribution of DP arguments at S- structure.

We are now in a position to be able to understand at least certain aspects of movement. Suppose that the principles of Theta theory determine that a DP argument must sit in position X. Suppose further that position X is not a position to which Case is assigned. If the DP remains in this position at S-structure, then the Case filter will be violated and the structure will be deemed ungrammatical. If on the other hand the DP can move to a position to which Case is assigned, then the movement will enable the Case Filter to be satisfied and the structure to be grammatical. This kind of movement might be said to be Case motivated and as we shall see, there are quite a few movements which follow this pattern. This is not the only motivation for movements, however, though we will not go into others at this point. The purpose of this section has been mainly to demonstrate how the interaction of grammatical principles applying at D-structure and S-structure can provide us with an understanding of movement phenomena.

2.3Traces

In the previous sections of this chapter we have concerned ourselves with the positions in which elements originate at D-structure and the positions they move to at S- structure. We might term these positions the Extraction site and the Landing site of a moved element. What is the status of the landing site at D-structure and the extraction site at S-structure? In (58) we introduced a restriction on movement called the Structure Preservation principle, which states that movements are not allowed to alter the basic X-bar nature of a structure. The result of this restriction is that the structure cannot be much different between D- and S-structure. In particular, we would not expect landing and extraction sites to appear at one level of representation but be absent at another. Thus, if we consider a passive structure in which the object moves to subject position, we can expect the object and subject positions to be present at both D- and S-structure:

(92) a |

[DP e] |

was found [DP the hideout] |

D-structure |

|

b |

[DP the hideout] was found |

[DP e] |

S-structure |

|

113

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

These representations indicate that the positions marked [DP e] are present in the structure, but empty and thus the movement does not change the structure but merely moves things about within the framework it provides.

There is reason to believe however, that the two empty positions in (92) are not the same as they display different properties. Consider the empty subject position in (92a). As this is a position to which something moves it would not be reasonable to think of it as being filled by some other element before the movement takes place. If there were something in this position at D-structure, presumably it would have to be deleted to allow the object to move into the position as general principles of structure do not allow two elements to occupy the same structural position. But if this element is always deleted, how could we ever be aware of its existence, let alone its nature. Moreover, if it were possible to delete elements in a structure to allow others to move into the vacated positions, we would expect far more movement possibilities that we actually observe. We would be able to move an object into a subject position of any verb, not just the passive ones:

(93)a [DP the FBI] found [DP the hideout] b *[DP the hideout] found [DP e]

Obviously, this is a situation we want to avoid and so we need to strengthen the Structure Preservation principle to prevent things in a structure from being deleted willy-nilly. Suppose we assume that lexical material that enters a structure cannot be altered by a movement. This maintains the Structure Preservation principle given that the lexical items that are inserted into a structure determine that structure to a great extent through notions of projection and selection, but it also prevents the deletion of lexical information once it has been inserted into a structure. This principle is called the Projection Principle:

(94)the Projection Principle

structures are projected from the lexicon at all levels

What this means is that anything that is inserted into a structure from the lexicon cannot change from one level of representation to another. If a verb is put into a structure, nothing can delete or alter this verb, turning it into a noun, for example. Also no movement can alter a verb’s selectional properties: a transitive verb will remain transitive at D-structure and S-structure even if the object is moved.

Under these assumptions, it must be that a passive verb loses its subject before it enters into a structure. There are numerous ways in which we might suppose that this can happen, but we will put the matter aside until we are in a better position to understand it. The general point is that as a result of being passivised, a verb fails to assign a -role to its subject and hence this position is absolutely vacant at D- structure. So with regard to the empty subject position in (92a) we can say that this position, whilst being present in the structure, is simply devoid of any contentful element and hence is vacant to be moved into.

Now consider the nature of the empty object in (92b): the extraction site of the moved object. By the Projection Principle, this object position must remain in the structure and cannot be deleted otherwise the transitive verb would find itself without an object and hence would be sitting in the structural position of an intransitive verb.

114

Theoretical Aspects of Movement

As this would alter the lexical nature of the verb, we conclude that it would be impossible. Yet if this position were simply vacant, like the subject position is at D- structure, we might expect that it could be the landing site for some other moved element. This, it turns out, is not true at all. Consider the following analysis which indicates several movements step by step:

(95) a |

[DP e] |

Susan said [[DP who] helped [DP Fred]] |

D-structure |

b who (did) Susan say [[DP e] helped [DP Fred]] |

after 1 movement |

||

c |

who (did) Susan say [[DP Fred] helped [DP e]] |

after 2 movements |

|

Both of these derived structures seem to be grammatical, but importantly they do not mean the same thing. In (95b) Fred is interpreted as the one who is helped and the interrogative pronoun who is the one doing the helping, as is indicated by the D- structure in (95a). But in (95c), Fred is the one doing the helping and who is the one helped. Under the assumption that -roles are assigned at D-structure, it cannot be the case that (95c) was formed from the D-structure (95a), but must be related to another D-structure, i.e. (96a):

(96) a [DP e] Susan said [[DP Fred] helped [DP who]]

b who (did) Susan say [[DP Fred] helped [DP e]]

The fact that (95c) cannot be interpreted in the same way as (95b) leads us to conclude that the movement indicated in the former is impossible and that the object cannot move into the vacated subject position.

The overall conclusion of this discussion then is that the empty positions that are present at D-structure are of a different nature to the empty positions present at S- structure which are created by movements: D-structure empty positions are vacant to be moved into, S-structure empty positions are not. Obviously this demands an explanation.

One possible account of the nature of empty extraction sites is that they cannot act as landing sites for subsequent movements because they are occupied. As two elements cannot occupy the same position and as we are not allowed to delete material, this would block movement into this position. There are two problems that this assumption faces: what element occupies the extraction site and why cannot we see it? Given the above discussion, there is no choice as to the identity of the element that occupies this position: it must be the moved element itself. No other element could either be moved into this position or be inserted into it from elsewhere without drastically changing the lexical information represented by the D-structure and this would violate the Projection Principle. But then we seem to be forced to accept that one element can occupy two positions.

We can get some understanding of this situation if we make the following assumption: when an element moves, it leaves behind a copy of itself in the extraction site. This copy is called a trace and is envisaged to be identical to the moved element in terms of its grammatical and semantic properties. Thus the category of the trace, its role in the thematic structure of the sentence and its referential properties are the same

115

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

as the moved element. The main way in which the trace differs from the moved element is that the trace has no phonological content and hence is unpronounced. We have already considered the possibility of phonologically empty but grammatically active elements when we discussed imperatives at the beginning of this chapter. A trace is another such element.

Traces are typically represented by a t, which bears an index which it shares with the moved element, both to link the trace and the moved element and to demonstrate that they have the same reference:

(97)a who1 did Susan say [Fred helped t1] b who1 did Susan say [t1 helped Fred]

The S-structure representations here demonstrate the movement of an interrogative pronoun from two different D-structure positions, marked by the trace. In (97a) who moved from object position and hence the sentence is interpreted as a question about the one who was helped. In (97b) on the other hand who moves from the subject position and hence the question is about the one who does the helping.

There are two views concerning the nature of traces. One is that a trace is related to but independent of the moved element. From this point of view a trace is a little like a pronoun referring to the moved element:

(98)a Charles1 was cheated t1 b Harry1 helped himself1

In these examples, the trace and the pronoun sit in object positions and refer to the subject in much the same way. From this perspective, the trace can be seen as having properties of its own independent of the moved element. We will see that there is some truth to this idea. However, traces are not like pronouns in one important way. As we see in (98b), the pronoun and its antecedent represent two different arguments, though they both refer to the same individual. Thus Harry is interpreted as the one who does the helping and himself is interpreted as the one who gets helped. With the trace in (98b) however, there is only one argument interpreted here: the one who was cheated. Because the verb is passivised, the subject’s -role is not present and so no element is interpreted as agent. Thus, it is as though the trace and the moved element share the same -role, which strictly speaking should not be possible due to the Theta Criterion. From this perspective, the trace and the moved element seem to be interpreted as a single element, capable of bearing a single -role. This single element is, however, spread out across a number of positions in a structure.

The notion of a chain might be useful here. We can see a moved element and its associated traces as a single object made up of several parts: like a single chain is made up from different links. Extending this analogy further, we can then refer to the different parts of a movement chain as the links of the chain. Thus, the movement in (99a) can be said to contain the chain represented in (99b):

(99)a this sentence1, you might not have seen t1 before b [this sentence1, t1]

This chain has two links: this sentence and the trace. We say that the moved element is at the head of the chain, while the trace is at its foot.

116

Theoretical Aspects of Movement

There is one more point we need to make in connection with positions involved in movement. Above we said that the landing site for a moved object in a passive structure is an empty position: the subject. This seems to make sense given that the subject position is an integral part of the sentence, without which we would not have a complete sentence. However, it is not always easy to identify a landing site as something that exists before the movement takes place. For example, consider the case of PP preposing, in which a PP is moved to the front of the clause:

(100) a |

Petra put the book [PP on the shelf] |

|

b |

[PP on the shelf]1, Petra put the book |

t1 |

This PP does not move to the subject position, which is already occupied by Petra. The position it moves to is to the left of the subject and it is not really a position that we easily claim to be integral to all sentences given that in many it is not filled at all.

Furthermore, this position has a number of things in common with an adjunct, in that an unlimited number of elements can undergo preposing:

(101)a Petra put the book [on the shelf] [without telling me] [yesterday]

b [yesterday]1, [without telling me]2, [on the shelf]3, Petra put the book t3 t2 t1

If we were to propose that these movements put the moved elements into empty positions, we would have to suppose the existence of an indefinite number of empty positions at the front of the clause which sit there waiting for something to move into them. This does not seem a reasonable assumption.

Moreover, there are instances that we might want to analyse as a case of movement where an element moves to a position that is blatantly not empty. For example:

(102)a we will not be moved b we won’t be moved

In (102b) it might be claimed that the negative element moves to the position occupied by the modal auxiliary and the two somehow join together to become a single word. Again there is something like an adjunction formed in this case with a word being created from two independent words, like a compound noun (in this case the ‘compound’ is a verb).

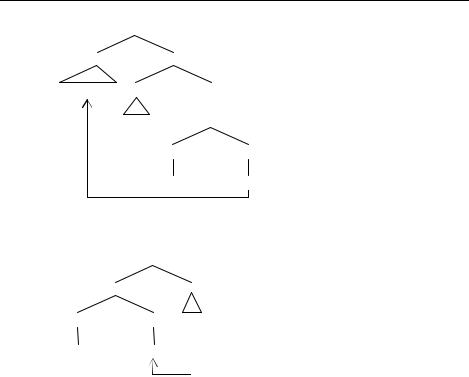

Because of examples such as these it has been proposed that there are two types of movement. One, known as substitution, moves an element into a vacant position. The other, called adjunction, creates an adjunction structure by the movement. Thus, PP preposing might be argued to move the PP to a position adjoined to the left of the clause:

117

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

(103) |

S |

|

|

PP |

|

S |

|

on the shelf1 |

DP |

VP |

|

|

Petra |

|

|

|

V© |

||

V PP

put t1

Similarly we might propose that some movements can move words to adjoin to other words, as is the case of the contracted negation:

(104) |

I© |

|

|

I |

|

I |

Neg |

t1 |

should |

n’t1 |

|

The irrelevant aspects of the analysis, such as the extraction site of the negative, need not detain us here. The important point is that the negative is moved from one position to a site adjoined to the modal.

One might wonder if adjunction conforms to structure preservation as it does seem to alter the structure from its D-structure condition. However, it should be noted that adjunction does not alter lexically determined aspects of structure and so is perfectly compliant with the Projection Principle which supersedes structural preservation. Moreover, adjunction is something which X-bar theory allows for and hence to create an adjunction structure is not to create something that violates the possible X-bar nature of the structure. In this way, adjunction movement does not radically alter structure and can be seen as structure preserving.

2.4Locality Restrictions on movement

The restrictions on movement we have mentioned so far have concerned its structure preserving nature. Not all structures which conform to these restrictions are grammatical, however, indicating that other restrictions are in operation. Most of the movements we have looked at have involved something moving within a single clause. Passivisation, for example, moves the object of a predicate to the subject of that predicate and obviously both the extraction site and the landing site are within the same clause. There are movements however, that move elements from one clause to another. Consider the following:

118

Theoretical Aspects of Movement

(105)a it seems [Fiona favours dancing] b Fiona seems [to favour dancing]

Given the near synonymy of these two sentences and the fact that the subject of seem in (105b) does not appear to be semantically related to this verb (Fiona is not the one who ‘seems’) we might assume that the latter is formed by a movement of the lower clause subject into the higher clause subject position:

(106) a |

[e] seems [Fiona to favour dancing] |

b |

Fiona1 seems [ t1 to favour dancing] |

This movement is known as raising as the subject of the lower clause raises to the subject of a higher clause.

Raising can apparently happen out of a number of clauses:

(107) a |

it seems [it is believed [it is unlikely [that Stan will steal diamonds]]] |

b |

[e] seems [to be believed [to be unlikely [Stan to steal diamonds]]] |

c |

Stan1 seems [to be believed [to be unlikely [ t1 to steal diamonds]]] |

Thus, at first sight it would seem that movement is unrestricted in terms of how far an element can be moved. But on closer inspection this might not be an accurate description of what is going on here. For example, note that in (107b) and (c) all the clauses that the subject is raised out of are non-finite and none of them seem to have subjects.

Suppose we try to move out of a finite clause instead:

(108)a *Stan1 seems [it is unlikely [t1 to steal diamonds]] b it seems [Stan1 is unlikely [t1 to steal diamonds]]

As we can see, a subject can be raised out of a non-finite clause into the subject position of a finite clause, but it cannot be raised out of a finite clause. Note that the finite clause in (108a) has a subject of its own: it. It is a fact about English finite clauses that they must have subjects and hence the sentence would be ungrammatical if the subject were missing for independent reasons. So this case differs from the grammatical movement in (107c) in two ways: the moved subject is moved out of a finite clause and it is moved out of a clause with a subject.

To control for these variables, let us consider a case where the movement is out of a non-finite clause with a subject:

(109)a it is unusual [for Eric to hope [Stan will steal diamonds]]] b *Stan1 is unusual [for Eric to hope [t1 to steal diamonds]]]

Again the result is ungrammatical, demonstrating that movement over a subject is itself enough to cause an ungrammaticality. But why would moving over a subject be a problem? If long distance movements are possible, it is hard to understand why the presence or absence of a subject should make any difference at all. However, if we suppose that long distance movements are not possible, though an element can move a long way via a series of short movements, we can come to an understanding of these observations. Consider the grammatical case of (107). As each subject position is

119

Chapter 3 - Basic Concepts of Syntactic Theory

empty it is possible for the moved subject to move into each one in turn, moving from one clause to the next each time:

(110) a [e] seems [[e] to be believed [[e] to be unlikely [Stan to steal diamonds]]]

b Stan1 seems [t1 to be believed [t1 to be unlikely [t1 to steal diamonds]]]

If there is a subject in one of these positions the moving subject would be forced to make a longer movement and if long movements are not allowed, we predict the result to be ungrammatical, which it is:

(111) a [e] is unusual [for Eric to hope [Stan to steal diamonds]]

b Stan1 is unusual [for Eric to hope [t1 to steal diamonds]]

We call this phenomenon, the boundedness of movement. For now it is enough to note that movement is bounded. We will look in more detail at the phenomenon in a subsequent chapter.

3 Conclusion

In this chapter we have briefly set down many of the theoretical mechanisms which we will be using in the rest of the book to describe syntactic phenomena in English. There is a lot more to say on theoretical issues and many differences of opinion as to how they should be formulated. However, as it is not our intention to teach all the details of the theory, but merely to use it, we will not go into these issues and the interested reader is directed to other text books, such as Haegeman (1994), Webelhuth (1995) or Radford (2004) for more detailed discussion on theoretical issues.

Check Questions

1Discuss rewrite rules: use the terms ‘category variables’, ‘head’, ‘complement’, ‘specifier’, ‘adjunct’, ‘recursion’, ‘category neutral’.

2Exemplify adjunction (i) to a head, (ii) to a bar-level projection, (iii) to a maximal projection, and state the corresponding rewrite rule.

3Explain the notion ‘projection’ and the way heads project their properties using expressions like ‘zero-level projection’, ‘bar-level constituent’, ‘maximal projection’.

4What is the difference between endocentric versus exocentric phrases?

5Which of the following properties of heads and/or phrases are predictable?

aendocentricity

bcategory

cargument structure

dsubcategorisation frame

epronunciation

fmeaning

120