grammatical foundations

.pdf

The syntax of inflection

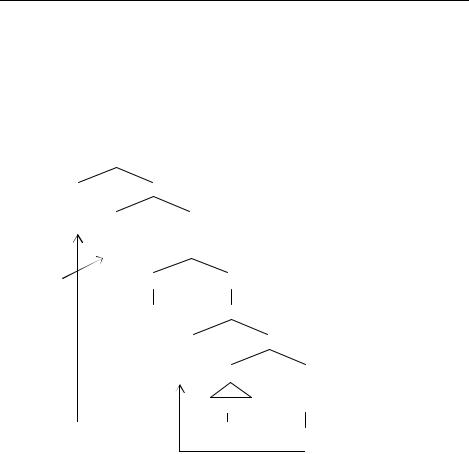

(20)IP

–I©

|

I |

vP |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

v© |

|

|

||||

have |

|

v |

|

vP |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-en |

|

v© |

|

|

||

|

be |

v |

VP |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V© |

|

|

|

|

|

-ing DP |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

they |

V |

PP |

|

stay with my parents

‘they have been staying with my parents’

In this case there are two aspectual morphemes as well as the inflection to be supported. The verb moves to the lowest one and cannot move further. Therefore two auxiliaries are inserted: be, determined by the progressive, is inserted onto the perfective morpheme which takes the phrase headed by ing as its complement, and have, determined by the perfective, is inserted onto the tense morpheme (in this case null) which takes the phrase headed by the perfective morpheme as its complement.

2.2Do-insertion

The use of have and be as supporting auxiliaries is therefore associated with the appearance of the aspectual morphemes whose presence necessitates the use of the auxiliary by ‘tying-up’ the verb so that it cannot support any other morpheme. The use of the dummy auxiliary do however, is a little different as it is not associated with the appearance of any aspectual morpheme and indeed cannot be used in the presence of one:

(21)a he did not arrive b he had not arrived

c *he did not have arrived

What determines the use of the auxiliary here? Obviously the verb is unable to support the inflection in this case, but this does not seem to be because it already supports another morpheme. In fact the verb is in its base form and there is no reason to think that there is any other verbal morpheme present. (21a) is simply the negative version of he arrived. Apparently it is the negative that blocks the verb from moving to support the inflection. To gain some understanding of what is going on here we need to briefly examine another kind of head movement which we will more thoroughly

221

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

discuss in the next chapter. In the formation of certain questions an auxiliary verb is moved to the other side of the subject:

(22) a |

Denise will dance |

will Denise dance? |

b |

Tim is tall |

is Tim tall? |

As we can see, both modal and aspectual auxiliaries can undergo this movement process. The observation of interest to us is what happens when there are more than one auxiliary:

(23)a Graham could be gardening b could Graham be gardening? c *be Graham could gardening?

Apparently, when there are more than one auxiliary, the first one is chosen to move. The reason for this seems to be that moving the first auxiliary involves a shorter movement than moving the second:

(24)a could1 Graham t1 be gardening? b be1 Graham could t1 gardening?

Travis (1984) proposed that this phenomenon can be explained by a restriction on head movement which prevents one head from moving over the top of another:

(25)the Head Movement Constraint (HMC)

a head must move to the next head position

The reason why (23c) is ungrammatical, then, is that if the aspectual auxiliary moves in front of the subject, it has to move over the modal. Whereas if the modal moves, it crosses over no other head. Now consider the case of verb movement in the presence of not:

(26) a |

he –ed ring the bell |

= |

he rang the bell |

b |

he –ed not ring the bell |

= |

*he rang not the bell |

The movement represented in (26a) appears to be grammatical whereas that in (26b) is ungrammatical. Again the difference between the two is that the grammatical movement is shorter. But if we want to use the HMC to account for the phenomena, it must be the case that the negative is a head as it is moving over this element that causes the problem. But, what kind of a head is the negative? It is situated between the inflectional element and the v/VP:

222

The syntax of inflection

(27)IP

–I©

I |

XP |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-ed |

X© |

|

|

|||

|

X |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

||

|

not |

|||||

|

|

the glass |

|

|

||

|

|

V |

||||

shatter

We know that the inflectional element takes a v/VP complement and therefore that the negative must be either V or v. As the complement of the negation is a v/VP it follows that the negative must be v, a light verb, as main verbs do not have verbal complements. Thus the analysis is:

(28)IP

–I©

I |

vP |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-ed |

v© |

|

|

|||

|

v |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

not |

DP |

V© |

|||

|

|

the glass |

|

|

||

|

|

V |

||||

shatter

Accepting this, we can account for the insertion of dummy do. The verb will not be able to move to inflection without violating the HMC. Apparently in English, the negative is not the sort of verbal element that can support tense and hence the only option available is to insert an auxiliary. As there is no aspectual morpheme to deem otherwise, the inserted auxiliary will be do:

223

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

(29) |

IP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

I© |

|

|

|||

the glass1 |

I |

|

vP |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-ed |

|

v© |

|

|

|||

do |

|

|

v |

VP |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

not DP |

V© |

||||

|

|

|

|

t |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

|||

shatter

‘the glass did not shatter’

Note that the inability of the negative to support the inflections is a language specific property and there are languages where this is exactly what happens. For example, Finnish negation shows the same agreement morphemes as its verbs do and in the presence of negation the verb does not inflect for agreement:

(30) |

menen |

– |

en |

mene |

|

|

go1.s. |

|

not1.s. go |

‘I go/I don’t go’ |

|

|

menet |

– |

et |

mene |

|

|

go2.s |

|

not2.s. go |

‘you go/you don’t go’ |

|

|

menee |

– |

ei |

mene |

|

|

go3.s |

|

not3.s. go |

‘he/she goes/he/she doesn’t go’ |

|

|

menemme – |

emme mene |

|

||

|

go1.pl. |

|

not1.pl. go |

‘we go/we don’t go’ |

|

|

menette |

– |

ette |

mene |

|

|

go2.pl |

|

not2.pl. go |

‘you (lot) go/you (lot) don’t go’ |

|

|

menevät |

– |

eivät |

mene |

|

|

go3.pl |

|

not3.pl go |

‘they go/they don’t go’ |

|

Because of its behaviour, the Finnish negative element is often called the negative auxiliary or even a negative verb. Moreover, in other languages the negative element surfaces as a bound morpheme on the verb, a situation very similar to the analysis we have given the aspectual markers in English. This is exemplified by the following Choctaw and Japanese sentences:

(31)ak-Ø-pi-so-tok 1s-3s-see-not-past ‘I didn’t see it’

(32)watashi-wa yom-anakat-ta

I read-not-past ‘I didn’t read’

224

The syntax of inflection

Besides the bound morpheme status of the negative, these languages differ from English in that verbal stems are allowed to support more than one bound morpheme and hence there is agglutination: complex words being formed from a series of inflectional morphemes. The point is that in these languages the negative element behaves like we have seen certain English light verbs do and hence they offer support for the suggestion that the negative can be analysed as a light verb.

Note that the presence of the negative will not affect the use of aspectual auxiliaries as these are inserted into the inflection position rather than moving to it:

(33) |

|

IP |

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

I© |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

– |

I |

|

vP |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-s |

|

v© |

||

have |

|

|

v |

|

vP |

|

not v©

v |

VP |

||

|

|

|

|

-en DP |

V© |

||

|

the glass |

|

|

V |

|||

shatter

‘the glass has not shattered’

2.3Tense and Agreement

From what has been said so far, we would expect that when there is no aspectual morpheme to be supported and no negation, there will be no need to insert an auxiliary as the main verb can move to support the inflection. Indeed this seems to be true as there is no inserted auxiliary in such cases and the tense morpheme appears on the verb:

(34)he arrive-ed

There is a problem however with the assumption that it is the verb that undergoes the movement in this case. This can be seen clearly when there is a VP adjunct. In the previous chapter, we argued that VP adverbs are adjoined to a v/VP higher than the position to which the verb moves. However, in the absence of any aspectual morphemes, it seems that the inflection appears on the verb inside the v/VP:

(35)he [vP quickly [vP count-ed his fingers]]

Thus, under these conditions it does not seem that the verb moves to the inflection, but rather that the inflection moves to the verb:

225

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

(36) |

IP |

DP I©

– |

I |

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

-ed AP |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

quickly |

DP |

|

|

v© |

|

|

|

|

|

he |

v |

|

VP |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

DP |

V© |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

his fingers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

count |

|

‘he quickly counted his fingers’

This analysis suggests that elements can move around in a structure quite freely and in particular both upward and downward movements are possible. But all the movements we have seen so far have been in an upward direction, including all the verb movements and the movement of the subject out of its original VP-internal position. It is possible that this might just be a bias of the small number of movement processes we happen to have reviewed so far. But it turns out, once one starts to investigate movements on a greater scale that the vast majority of them have an upward orientation, which might lead us to the conclusion that perhaps it is our analysis of the small number of apparent cases of downward movements that is at fault. One reason to believe that downward movements are not possible is that it is ungrammatical for certain things to move downwards, which is difficult to explain if such movements are allowable. For example, the verb always moves to the light verb positions and light verbs never move to the verb:

(37) a [vP he –v [VP the ball hit]] |

he hit1 the ball t1 |

b [vP he –v [VP the ball hit]] |

*he t1the ball hit1 |

If downward movements are a possible grammatical process, we have no explanation for why (37b) is ungrammatical in English and can only resort to stipulation that English verbs move upwards in this case. For such reasons, during the 1990s the idea of downward movement was abandoned and all seemingly downward movements were reanalysed as involving upward movements instead.

A further problem with the analysis in (36) is the explanation of why the verb cannot move to the I position. We have seen that verbs are perfectly capable of moving, so why this is not possible to the inflection position is quite mysterious. Some, who accepted the ‘I-lowering’ (affix lowering) analysis, have suggested that the

226

The syntax of inflection

verb cannot escape the VP because of its -assigning properties, pointing to the fact that aspectual auxiliaries and copular be, which do not assign -roles, can appear in I (Pollock 1989).

But from our perspective, these elements appear in I by being inserted there and do not undergo movement at all and so there may be other reasons for the fact that they behave differently to main verbs. It is also not entirely clear why the verb can move within the vP, sometimes through as many as three light verb positions and not have any trouble with its -assigning properties. Something rather stipulative and ultimately circular has to be claimed to try to account for this fact. For example, we might assume that the inflection has some property, which light verbs lack, that means that if a thematic verb moves to I it cannot assign its -roles. Often it is claimed that the inflection is ‘too weak’ to support the verb’s -assigning requirements. But the weakness of an element only correlates with the ability of the verb to move to that element, which is the very reason for proposing the notion in the first place!

Before trying to solve these puzzles, one more mystery should be introduced. Our assumptions have been that auxiliaries are inserted into a structure to support bound morphemes when the verb is unable for one reason or another to do so. Obviously a free morpheme does not need supporting either by the verb or an auxiliary. This would predict that when the inflection appears as a free morpheme, i.e. a tense or the infinitival marker, there will be no need for an inserted auxiliary to accompany an aspectual morpheme. But this prediction seems to be false:

(38)a he will have gone

b she might be worrying

c for you to be seen here would be disastrous

The obvious question is what are these auxiliaries supporting? Note that any element that appears after a free inflectional element is always in its base form. Thus, either the auxiliaries are supporting nothing, which throws doubt on their treatment as inserted empty elements, or they are supporting a null morpheme. The latter assumption allows us to maintain our approach but it raises the subsequent question of what this morpheme is.

The facts concerning this morpheme are that it is only present when there is a free inflectional element and the morpheme always follows the inflection.

(39)a he will leave-

b they must haveleft c we might beleaving d to beseen

When there is a bound inflectional element, i.e. a tense morpheme, the null morpheme is not present:

(40) a |

*we did havegone |

we had gone |

b |

*they did begoing |

they were going |

c |

*I did leave- |

I left |

227

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

(40c) is of course grammatical, but only with special stress on did and used to assert something that has previously been denied. Thus, it does not mean the same thing as I left and in fact cannot be used to mean this.

These observations show that this zero morpheme is in complementary distribution with tense and thus the straightforward conclusion is that it IS tense. But how can this be if tense is an inflectional element and the zero morpheme is not in complementary distribution with modal auxiliaries, which are also inflectional elements? What the data show is that it is not modals that tense is in complementary distribution with, but the zero tense morpheme that accompanies the modal and hence the conclusion is that if modals are of the category ‘inflection’, then tense is not of this category. Given that tense is situated in front of the VP, we can assume that it is a head that selects a verbal complement and given that it follows the inflectional elements (i.e. modals) it must project a verbal phrase. In other words, tense is yet another light verb:

(41)IP

DP I©

I vP

modal v©

v VP

tense DP |

V© |

V

This analysis raises the question of what category ‘inflection’ is if it excludes the tense morpheme, and specifically what occupies this position when there is no modal? To answer this, consider the properties of modal auxiliaries. It is a traditional idea that they are not actually in complementary distribution with tense, as in some sense they display a kind of tense inflection:

(42) |

may |

might |

|

can |

could |

|

shall |

should |

|

will |

would |

|

(must) |

|

Virtually all modals come in pairs, which might be claimed to represent a distinction between past and present. The use of these forms supports this view:

(43)a I think I am going

b I thought I was going c *I thought I am going

228

The syntax of inflection

(44)a I think I can go

b I thought I could go c *I thought I can go

Although I am very much simplifying things here, we can see in (43) that there is some requirement that embedded clauses have a matching tense specification to the main clause and hence the ungrammaticality when the main clause is in the past tense and the embedded clause is in the present. (44) demonstrates something very similar happens with certain modals and hence that modals seem to be specified for tense (or at least they are not themselves in complementary distribution with a tense specification wherever in the clause that specification is made). However, what modals are in complementary distribution with is agreement: modals do not have forms that are dependent on the properties of the subject:

(45)a he/she/I/you/we/etc. may/will/would/can/etc. b *he/she wills/cans/woulds/etc.

Perhaps, then, what ‘inflection’ is, is agreement and this is expressed either as a morpheme dependent on properties of the subject, or a modal. Of course in English the visible tense and agreement morphemes are expressed as a single form, s. But in many languages tense and agreement are expressed as separate morphemes, as they are in Hungarian:

(46) |

elmen-t-em |

I left |

|

elmen-t-él |

you left |

|

elmen-t- |

he/she left |

|

elmen-t-ünk |

we left |

|

elmen-t-etek |

you (lot) left |

|

elmen-t-ek |

they left |

In this paradigm, the past tense is represented uniformly as an independent morpheme t and the agreement morphemes differ depending on the person and number of the subject.

The inflectional head has a very important role in determining the nature of the following tense head. As we have seen, modals determine that tense will appear as a null morpheme, but note that its content, i.e. past or present, can be recovered from the modal itself, which inflects for tense. When the inflectional element is a null agreement morpheme, the form of the tense will be partly determined by the agreement morpheme and partly by the tense itself. So if the tense is past then it will be realised as ed (or one of its irregular forms) no matter what the agreement is. But if the tense is present, it will be realised as s when the agreement is third person and singular and as a zero morpheme when the agreement is something else:

(47)a [IP - can [vP - …]]

b [IP - 3.s. [vP - -s/-ed …]] c [IP - ~3.s. [vP - /-ed …]]

We have not yet mentioned the infinitival marker to. What is its status? Is it a nonfinite agreement morpheme, similar to a modal, or is it a non-finite tense morpheme

229

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

that is accompanied by null agreement? For now I will assume that it is a tense element and demonstrate later that this seems to be correct.

2.4Movement to tense and I

Having separated tense and agreement (=inflection), let us consider their properties separately. Tense is obviously a bound morpheme triggering movement of the verb or insertion of an auxiliary when the verb is unable to move. But what about the null agreement morpheme, is this a bound morpheme or not? If it is, it will need supporting and we would expect verbs and auxiliaries to appear as high as the I node as we do not want to claim that the inflection lowers onto the tense. On the other hand, agreement might be like the modals and be a free morpheme, in which case we would expect nothing to move to I. The data are complex and often depend on other assumptions as to how to interpret them. Basically there appears to be a difference in how verbs and auxiliaries behave. Auxiliaries appear to be able to achieve a higher position than the main verb, indicating that while the verb can move to tense it cannot move to I, whereas auxiliaries can be in I.

As we have seen, adverbs and the negative head can appear in a number of positions within the v/VP, with adverbs being able to adjoin to most phrases above the verb and negation taking most phrases above the verb as its complement:

(48)a will (quickly) have (quickly) been (quickly) being (quickly) hidden b will (not) have (not) been (not) being (not) cooked

Both negation and VP adverbs can also precede the non-finite marker, indicating that this is a tense element that stays inside the vP:

(49)a for him quickly to have left was a relief

b for him not to have said anything was strange

However, neither VP adverbs nor negation can precede modals:

(50)a *quickly will leave b *not will leave

And neither of them can appear adjoined to a phrase that the verb has moved out from:

(51)a *he will have seen1 quickly [VP the papers t1] b *he will have seen1 not [VP the papers t1]

It thus seems that these elements appear anywhere inside the vP as long as they are below the I and above the surface position of the verb.

Now, when there is no modal, an auxiliary inserted to bear tense behaves as though it is in I as no adverb or negation can precede it:

(52) a |

I have quickly marked the essays |

– |

*I quickly have marked the essays |

b |

I have not graded the papers |

– |

*I not have graded the papers |

This supports the assumption that the inflection is a bound morpheme that needs supporting by a verbal element. With main verbs, however, we find that the tensed verb appears below the adverb and the verb cannot support tense in the presence of negation:

230