grammatical foundations

.pdf

Verb Types

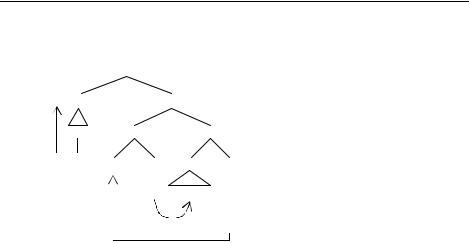

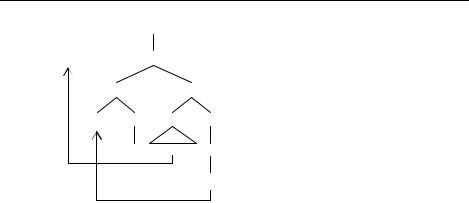

assumption of a position to which the verb moves. If we assume that this is indeed a light verb, we can account for the Case assignment to the object as well:

(68) |

vP |

|

|

|

|

||

DP |

|

|

|

v© |

|

|

|

there |

v |

|

VP |

|

|

||

|

arrived1 v |

|

DP |

V© |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

a letter |

|

|

|

|

e |

|

V |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case |

|

|

t |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

Obviously, this light verb is not the same as the one we get in the causative construction as there is no causative interpretation here and no agent -role assigned. In fact, this verb does not appear to have much of a meaning at all. But this might be an advantage in accounting for the other properties of the there construction. Recall Burzio’s generalisation: only a verb which assigns a -role to its subject assigns an accusative Case. The causative light verb fits this restriction well: it assigns an agent-role to its subject and an accusative Case to the theme in the specifier of the VP. If the abstract light verb in the there construction is restricted by this, then the fact that it assigns no -role to the there subject, accounts for why we do not find simple accusative DPs in the theme position.

However, we do not want to say that there is absolutely no connection between the abstract light verb and its subject, as there are restrictions placed on it: the subject must be there and not it. Thus, suppose that there is a special argument of this predicate, which receives no actual -role from it but is restricted by it. A similar notion of ‘quasi-argument’ has been proposed for cases such as:

(69)a it rained b it snowed c it’s windy

The it subjects that accompany weather predicates are clearly not arguments as they have no referential content, but they are somehow not quite as empty as the expletive it in examples like (62b).

One indication of the difference between the quasi-argument it and the expletive it is that only with the former is a purpose clause licensed, i.e. a clause that acts to modify a predicate by providing a purpose for the described event:

(70)a it rains [to feed the plants]

b *it seems [that Rob is rich] [to impress the neighbours] c Rob seems [to be rich] [to impress the neighbours]

The intended interpretation of (70b) is that Rob pretends to be rich in order to impress the neighbours, an thus it is the ‘seeming’ rather than the ‘being rich’ that is being

171

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

modified by the purpose clause. The ungrammaticality of this sentence with this interpretation demonstrates that expletive it is unable to license this kind of modifier. When the thematic subject is raised, however, the purpose clause is grammatical. The quasi-argument weather predicate it appears to behave like a thematic argument in this respect as it does license a purpose clause. Obviously I do not want to claim that the there subject in there constructions is the same thing as a weather predicate’s quasiargument subject.

But I have discussed this phenomenon to demonstrate that there are different degrees of argumenthood and the claim I want to make is that there is somewhere between a thematic argument and an expletive, which is supported by the fact that purpose clauses can appear with there subjects:

(71)a water ran down the cliff face [to hide the mouth of the cave]

b there ran water down the cliff face [to hide the mouth of the cave]

Now let us suppose that this connection between the light verb and its restricted subject, although it is not enough to license accusative Case, is strong enough to license a Case that can be born by indefinites (perhaps partitive). We then have an explanation for why the post-verbal theme is restricted to indefinite DPs. All in all then, the supposition of a (very) light verb in the there construction leads to quite an explanatory account of many of its properties.

2.4Transitive verbs

It is time we turned our attention to those verbs that traditional grammars seem to consider more central: transitive and intransitive verbs. What we have said so far has far reaching repercussions for the analysis of these verbal subcategories. We will start discussing these with respect to the transitives.

A transitive verb is one that has an object, i.e. a DP complement, and a subject. The subject may be agent and the object patient, or the subject could be an experiencer and the object theme. Patient and theme, from this perspective, differ in terms of a notion of affectedness: a patient is affected by the action described by the verb while a theme is unaffected by it:

(72)a Sam sawed the wood (to pieces) b Sam saw the wood (*to pieces)

In (72a) we have the past tense form of the verb to saw, Sam is an agent and the wood is patient. In this cases a resultative modifier like to pieces can be used to describe the state of the object after being acted upon. In (72b) we have the past tense form of the verb to see, Sam is an experiencer and the wood is an unaffected theme. Obviously in these cases the resultative is inappropriate because nothing directly happens to the object as a result of being seen. We will put the case of the experiencer–theme type transitives to one side for the moment and start our discussion with the agent–patient type.

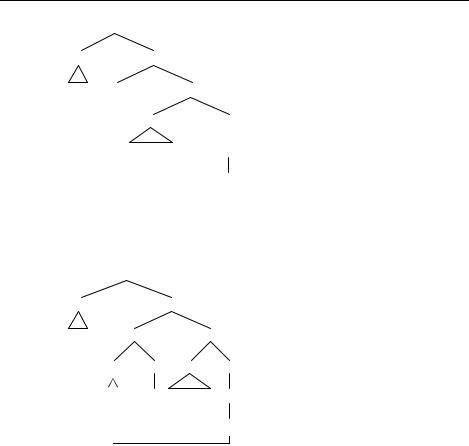

Above we found that the agent -role was assigned by a light verb which takes a VP complement. If we assume that the patient is a kind of theme, we might expect that it is assigned to the specifier of a main verb:

172

Verb Types

(73) |

vP |

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

v© |

|

|

Pete |

v |

|

VP |

||

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

|

|

e |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the letter |

V |

|

posted

Again, if this were the final analysis of the construction we would derive the wrong order with the verb following its object. Once again, however, we might assume that the main verb raises to the light verb, presumably because of its bound morpheme status:

(74) |

vP |

|

DP |

|

v© |

Pete |

v |

VP |

posted1 v DP V©

e the letter V

t1

Thus the transitive receives the same analysis as the causative construction, which is not surprising as causatives are the transitive use of ergative verbs.

What is the light verb in this case and how is the main verb related to the subject? We might try the assumption that the empty light verb in this case is the same as the one in causative constructions. From this point of view we would have the following correspondence:

(75) a |

Mark made the bed |

= Mark made the bed be made |

|

b |

Harry hit Bill |

= |

Harry made Bill be hit |

c |

Richard wrote the letter |

= |

Richard made the letter be written |

But while the transitive statements in (75) do entail the relevant causative, in that if Mark makes the bed, then the bed comes to be made and Mark had a hand in causing this to come about, the two are not exactly the same. Particularly, it is not only the case that subjects in (75) caused the event described by the verb to take place, but that the subjects are the ones who actually did it! In other words, these subjects are not just agents, they are agents of the relevant predicates. This might therefore argue that the relevant structure should be:

173

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

(76)VP

|

DP |

|

|

V© |

||

Harry |

V |

DP |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hit |

Bill |

|||

|

agent |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

patient |

|

But then the -roles are assigned to different structural positions and the UTAH cannot be maintained.

2.4.1 Evidence from passives

There is some evidence that the correct structure should be something like (74) however. This comes from the fact that transitive verbs can undergo passivisation. When a verb is passivised, it loses its agent and the object becomes the subject:

(77) a |

Mark made the bed |

– the bed was made |

|

b |

Harry hit Bill |

– |

Bill was hit |

c |

Richard write the letter |

– |

the letter was written |

Even under a less strict view of the UTAH than we are attempting to keep to here, one would like to assume that the object is generated in the same place in active sentences and their passive counterparts. This has been the assumption since the beginning of generative grammar in the 1950s. Thus, the object is generated in object position in the passive, but moves to the subject position. Presumably the only reason it would do this is to get Case. Thus while in the active structure the object gets Case in object position, this ceases to be a Case position in the passive and hence not only does a passive verb lose its subject, it also loses the accusative Case assigned to its object. Again, these are fairly standard assumptions about the analysis of the passive which have been proposed since the 1980s.

Interestingly, the passive is a construction which conforms to Burzio’s generalisation: the verb stops assigning a -role to its subject and loses the ability to assign accusative to its object. But Burzio’s generalisation is a description of a state of affairs, it is not an explanation of that state of affairs. What we need is something that links the two properties. In previous examples we have seen a way to link the -role assignment to the subject and the accusative Case assignment to the object: through the light verb which is assumed to do both:

174

Verb Types

(78) |

vP |

DP v©

Pete v |

|

VP |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

DP |

V© |

|||

agent |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the letter |

V |

||

|

accusative |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

posted

If the light verb ceased to be there, both the agent -role and the accusative Case would be lost in one step. What would be left is the main verb with its patient argument which would lack Case and hence have to move to subject position:

(79)VP

DP V©

the letter V

posted

Thus, if we analyse the passive construction as involving the loss of the light verb, we readily account for its two most salient properties.

We might extend this analysis to take into consideration other aspects of the passive construction. It has been argued that one of the central aspects of the passive is the appearance of the passive morpheme. The passive morpheme appears in all English passives, no matter what else happens. Thus, not all passives involve an object moving to subject position (80a), and while some passives contain a by phrase reintroducing the missing subject, not all do (80b). Furthermore, most passive constructions involve a passive auxiliary be, but not all (80c):

(80)a it is expected that Pete will post the letter b the letter will be posted (by Pete)

c I will expect [the letter posted by noon at the latest]

In all these examples however, the passive verb has the passive morpheme. We can incorporate this into our analysis of the passive making use of an idea presented above, that certain bound morphemes can be analysed as light verbs. Suppose we assume that the passive morpheme is a light verb which replaces the agentive light verb of the active. As the passive light verb does not assign a -role to its subject, it will not be able to assign a Case to the theme in the specifier of the VP and hence this argument will have to move to subject position. Moreover, the bound morpheme status of the passive light verb will force the main verb to move in order to support it:

175

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

(81) |

vP |

v©

v VP

post1 v DP V©

ed the letter V

t1

From this perspective, then, the analysis of the passive involves replacing the agentive light verb with a non-agentive passive light verb, most of the other aspects of the passive construction follow straightforwardly from this.

A crucial point to make at this point is that this analysis of the passive would simply be unavailable if we supposed that the structure of the active were to be (76) and not (74). Inasmuch as this analysis helps us to understand the passivisation process any better, then, it can be used as evidence in favour of the assumption of (74).

2.4.2 Extended projections

Yet if this is so, we still face the problem that the subject of an active transitive verb is interpreted as the subject of that verb and not of some independent abstract light verb. To understand this, it is essential to understand the relationship between light verbs and thematic verbs in general. Recall that the semantic contribution of a light verb to a construction is somewhat reduced from its full thematic usage:

(82)a I gave Charlotte chocolates

b I gave Kevin a kick in the pants c I kicked Kevin in the pants

In (82a) the verb give is used fully thematically and it contributes its full descriptive content to the whole sentence: the agent is in possession of the chocolates, and does something (i.e. gives) that results in the recipient in possession of the chocolates. But in (82b), where give is used as a light verb, it does not contribute its whole semantic content. For example, it cannot be claimed that anything has been given here and certainly Kevin does not end up in possession of a kick! Instead the main descriptive content comes from the deverbal noun and hence the similarity of meaning of (82b) and (c). It seems that semantically speaking, the complement of the light verb is the main contributor to the construction and although light verbs do contribute something, their contribution is often subtle and always dependent on the thematic complement. This shows a very different relationship between a light verb and its complement and a thematic verb and its complement. In the latter case, the thematic verb selects and imposes restrictions on its complement whereas in the former, the light verb is in some ways selected for and restricted by its complement: recall that unaccusative verbs do not appear with the abstract causative light verb, but ergatives do. Suppose then that the main semantic aspects of a light verb are determined by its thematic complement

176

Verb Types

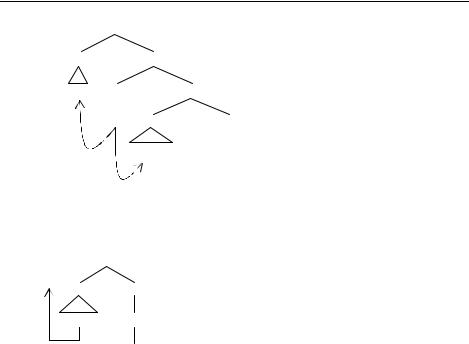

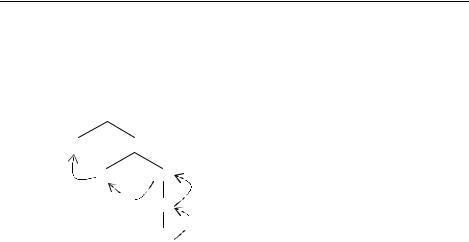

and that these are passed up to it by a process similar to projection – something which has been called extended projection, in fact. It would then depend on the thematic verb how the argument of the light verb was to be interpreted, as a causer, not directly seen as the agent of the thematic verb, or as a direct agent of that verb. We might visualise this in the following way:

(83)vP

DP |

|

v© |

||

|

|

|

|

|

-role |

v |

VP |

|

|

|

|

projection |

||

|

|

|||

extended V©

projection

projection

V

If this is right, then the agent subject of the light verb involved with transitive verbs will receive its -role indirectly from the main verb, via the light verb, and hence will be interpreted as the argument of the thematic verb. Of course the actual assignment of the -role will be dependent on the presence of the light verb, as by the UTAH roles such as agent can only be assigned to the specifier of a light verb.

2.4.3 Agent and experiencer subjects

What about the event structure of a transitive construction? Above we argued for an isomorphism between the structure of the VP and the structure of the event it describes such that each part of the VP corresponds to a separate sub-event. If transitive verbs involve an agentive light verb, and hence there are two parts to the verbal complex, we should expect that the event described by a transitive verb should consist of two subevents. But we have just seen that transitives are not causative: Harry hit Ron does not mean that Harry does something that causes Ron to get hit. However, there is not necessarily a direct relationship between what the subject does and the object getting hit. Consider the following:

(84)a Harry hit Ron with his hand b Harry hit Ron with a stick c Harry hit Ron with a stone

We can see from these examples there is a sense in which there are two parts to a hitting event: somebody does something and somebody or something gets hit as a more or less direct result of this. There is obviously a very subtle difference between this interpretation and a causative one, which we will not attempt to describe here. The point is that the event structure of the transitive can be represented in a similar way to that of a causative:

(85)e = e1 → e2 : e1 = ‘Harry did something’

e2 = ‘Ron got hit’

Now let us turn our attention to verbs of perception which take experiencer subjects.

177

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

(86)a Sally saw a ghost

b Harry heard the news c Fred fears the dark

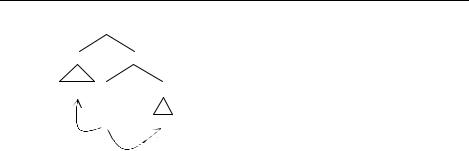

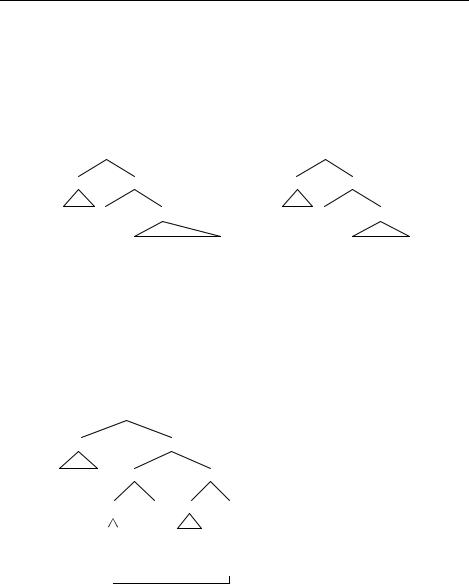

The obvious question that needs to be asked is whether the experiencer subject occupies a similar position to an agent subject or a different one. The choices would seem to be to place the experiencer in the specifier of an abstract light verb, or to place it in the specifier of the thematic verb:

(87) a |

vP |

|

b |

VP |

|

||

DP |

|

|

v© |

DP |

|

|

V© |

Harry |

v |

VP |

Harry |

V |

DP |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

heard the news |

heard |

the news |

|||

One observation that might be relevant here is that there are some verbs which take both agent and experiencer arguments. With these verbs, the agent always precedes the experiencer:

(88)a Freddy frightened me b Ursula upset the waiter

c Dennis disappointed his parents

Assuming that the agent is in the specifier of a light verb, these observations suggest that the experiencer is in the specifier of the thematic verb, like theme arguments:

(89) |

vP |

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

v© |

|

|

Freddy |

v |

|

VP |

||

fightened1 v |

DP |

V© |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

me |

V |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t1 |

|

This would support the structure in (87b) which has the experiencer in the specifier of the thematic VP, as in (89).

A second observation that seems to support (87b) concerns the event structure of transitive verbs with experiencer subjects. Certainly there does not appear to be a causative relationship between what the subject is interpreted as doing and what happens to the object. (86c), for example, does not appear to be interpretable as Fred doing something that results in the dark being feared. Instead it seems that these sentences express a simple state of affairs with no sub-events:

178

Verb Types

(90) |

e = e1 : e1 = ‘Fred fears the dark’ |

If there is an isomorphism between event structure and VP structure and (90) is the correct analysis of the event structure involving an experiencer subject transitive verb, then (87b) appears to be the correct structure of the VP.

However, an obvious disadvantage of (87b) is that the theme is placed in the complement position which is counter to what we have previously discovered. If the theme goes in the specifier of the thematic verb, then there is no alternative than to include the experiencer in a higher position which would mean adding an abstract light verb. A further disadvantage of (87b) is that transitive verbs with experiencer subjects can be passivised. We have analysed passivisation as a process which removes the light verb responsible for the assignment of the -role to the subject and the Case to the object, replacing it with the passive morpheme. If there is no light verb responsible for assigning the experiencer -role, it is not at all clear how these verbs could undergo passivisation: what would the passive morpheme replace and why would the experiencer -role and accusative Case go missing? Moreover, the passivisation of these verbs casts doubt on the assumption that they have a simple event structure. Passivisation of agentive verbs by getting rid of the agentive light verb turns a verb with a complex event structure into one with a simple one:

(91) a |

Harry hit Ron |

|

|

|

e = e1 → e2 |

: e1 |

= ‘Harry did something’ |

b |

Ron was hit |

e2 |

= ‘Ron was hit’ |

|

|

||

|

e = e1 |

: e1 |

= ‘Ron was hit’ |

But if experiencer transitive verbs have a simple event structure and we remove the experiencer, what are we left with? Surely we cannot be left with half an event! This would argue that the event structure of experiencer transitives is similar to that of agentive transitives:

(92) a |

Fred fears the dark |

||

|

e = e1 → e2 |

: e1 |

= ‘Fred experiences something’ |

|

|

e2 = ‘the dark is feared’ |

|

b |

the dark is feared |

|

|

|

e = e1 |

: e1 |

= ‘the dark is feared’ |

To argue for this in any depth, however, would take us beyond the scope of this book and into areas such as psychology and philosophy. Therefore we will assume this to be the case, based on the linguistic arguments so far presented.

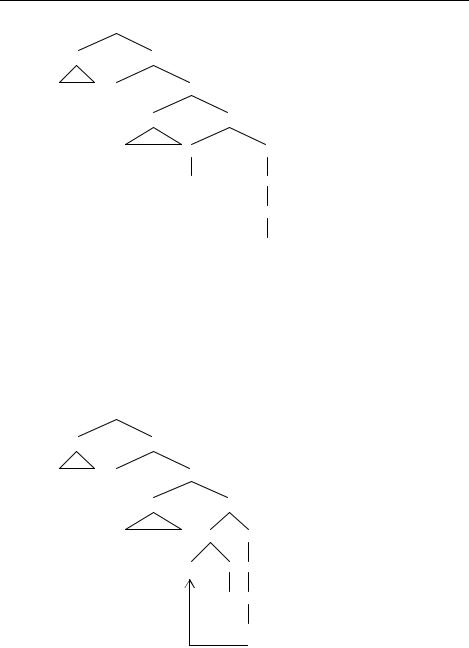

2.4.4 Multiple light verbs

If we assume that experiencers are assigned their -roles in the specifier position of a light verb, we face a problem in analysing verbs with agent and experiencer arguments as in (88). What is puzzling about these verbs is how they can exist at all, given our assumption that agent and experiencer receive their -roles in the same position. The only analysis available to us, if we wish to maintain the UTAH, is to assume that there are two light verbs in these constructions, one for the agent and one for the experiencer:

179

Chapter 5 - Verb Phrases

(93) |

vP |

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

v© |

|

Ursula |

v |

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

v© |

|

e |

|||

|

|

|

the waiter v |

VP |

eV© V

upset

The event structure of these verbs seems to support this analysis as it does seem rather complex:

(94) |

e = e1 → e2 → e3 : e1 |

= ‘Fred did something’ |

|

e2 |

= ‘I experience something’ |

|

e3 |

= ‘I am frightened’ |

To get the right word order we will have to assume that the verb moves to the highest light verb and in fact, the verb will have to move to them both, one after the other, if abstract light verbs are bound morphemes:

(95) a |

vP |

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

|

v© |

|

|

Ursula |

v |

|

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

v© |

|

e |

|

|||

|

|

|

the waiter |

v |

VP |

upset1 v V©

eV t1

180