- •Foreword

- •Preface

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Prologue

- •1.9 Expansion of the Greater Omentum

- •3: Distal Gastrectomy

- •4: Total Gastrectomy

- •5.2 Part II: Thoracic Manipulation

- •6: Right Hemicolectomy

- •7: Appendectomy

- •8.6 Internal Pudendal Artery and Its Branches

- •8.13 Lateral Ligament

- •8.16 Fascia Propria of the Rectum: Part II

- •9: Sigmoidectomy

- •13: Hemorrhoidectomy

- •14: Right Hemihepatectomy

- •15: Left Lateral Sectionectomy

- •16: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- •17: Open Cholecystectomy

- •Bibliography

8.6 Internal Pudendal Artery and Its Branches |

229 |

|

|

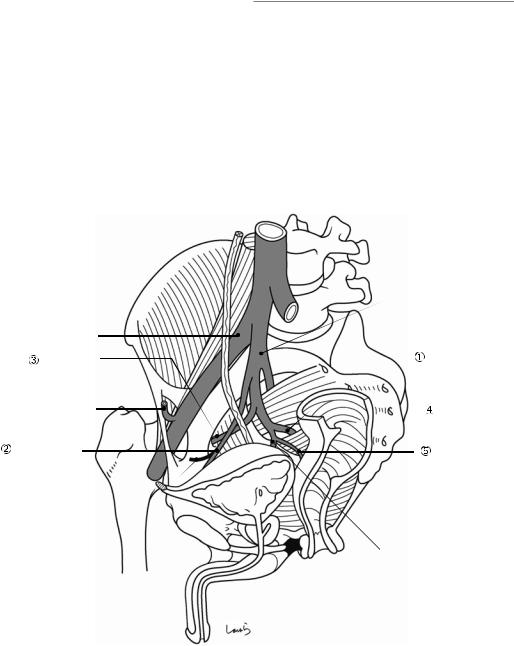

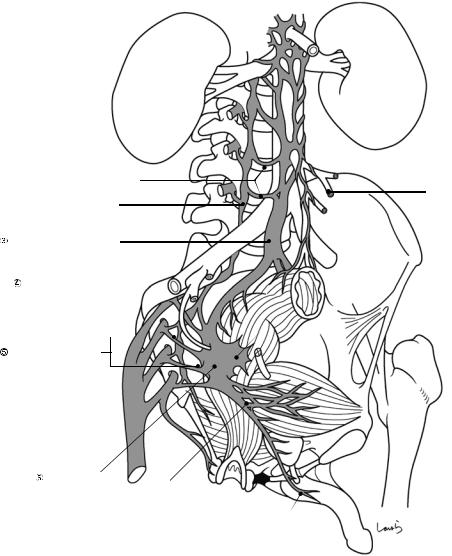

8.5\ Internal Iliac Artery and Its

Branches (Fig. 8.5)

Superior gluteal artery: Passes through the suprapiriform foramen out of the pelvis and supplies the gluteal region.

Superior vesical artery: Supplies the upper urinary bladder after branching off from the lateral umbilical ligament. The lateral umbilical ligament is a remnant of the umbilical artery, which returns blood from the fetus to the placenta during fetal life, and, just like the round ligament of the liver formed from the umbilical vein, is a cord-like structure with a collapsed lumen. Along the ligament is a cord-like bulge of the peritoneum referred to as the medial umbilical fold (see Fig. 19.6 in Chap. 19 on the anatomy of the inguinal canal and surrounding structures).

Obturator artery: Passes through the obturator canal out of the pelvis and supplies the adductor muscles.

Internal pudendal artery: See Sect. 8.6.Middle rectal artery

Inferior vesical artery

8.6\ Internal Pudendal Artery

and Its Branches

The internal pudendal artery passes through the infrapiriform foramen out of the pelvis, turns around the ischial spine, and travels through the lesser sciatic foramen into the ischiorectal fossa (beneath the levator ani muscle). The inferior rectal artery is a branch of this artery.

|

Int. iliac a. |

Ext. iliac a. |

|

Obturator a. |

Sup. gluteal a. |

|

|

Inf. epigastric a. |

Int. pudendal a. |

|

|

Sup. vesical a. |

Mid. rectal a. |

Lateral umbilical lig. |

|

Inf. vesical a.

Inf. vesical a.

Fig. 8.5 Internal Iliac artery and its branches

230 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

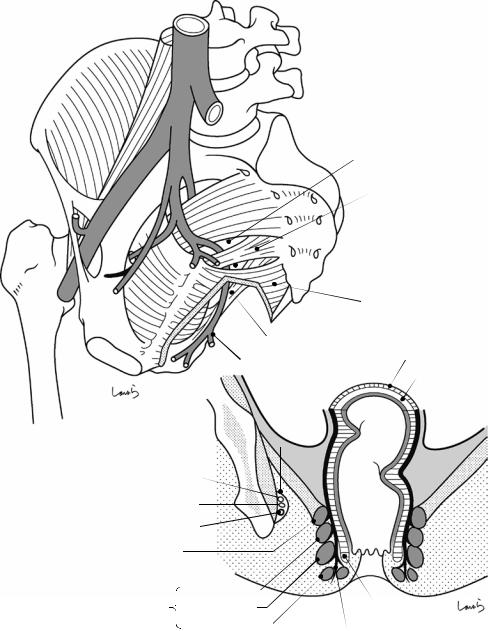

a

Infrapiriform foramen

Sacrospinous lig.

Lesser sciatic foramen

Levator ani

Sacrotuberous lig.

Inf. rectal a. Outer longitudinal m.

Inf. rectal a. Outer longitudinal m.

Inner circular m.

b |

Pudendal canal |

(Canal of Alcock) |

Int. pudendal a. |

|

||

Pudendal n. |

|

||

Int. pudendal v. |

|

||

Puborectalis m. |

|

|

|

Ext. anal |

I Deep |

|

|

II Superficial |

Int. anal sphincter |

||

sphincter |

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

III Subcutaneous |

|

|

|

|

Conjoined longitudinal |

|

|

|

muscle fibers |

|

Fig. 8.6 Internal pudendal artery and its branches

8.8 Anatomy of the Nervous System (Autonomic Nervous System) |

231 |

|

|

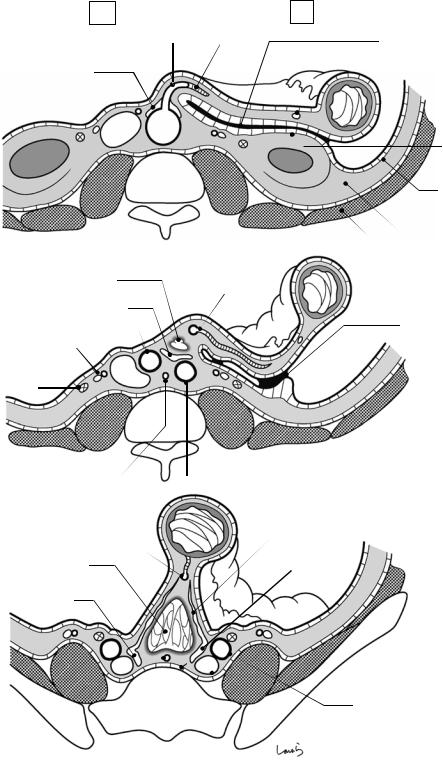

Figure 8.6b shows a schematic diagram of the ischiorectal fossa on frontal cross section of the pelvis. The internal pudendal artery, along with the internal pudendal vein and the pudendal nerve, runs through the fascial canal formed along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa. This canal is referred to as the pudendal canal or canal of Alcock.

This figure also clearly shows the positional relationship between the internal and external anal sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is a thickening of the inner circular muscle of the rectum at the terminal portion. The outer longitudinal muscle becomes the conjoined longitudinal muscle fibers and enters the space between the internal and external anal sphincters.

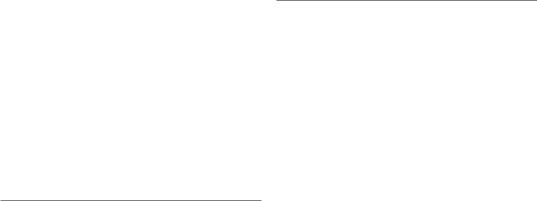

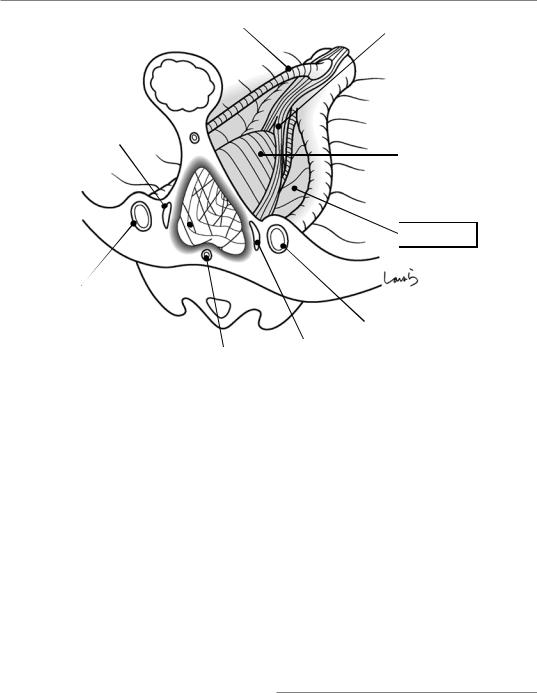

8.7\ Anatomy oftheNervous System (Somatic Nervous System) (Fig. 8.7)

Lumbar Plexus Formed by the anterior branches of the L1–L5 spinal nerves and gives two major branches, the femoral and obturator nerves.

•\ Femoral nerve (L1–L4): Descends between the femoral and iliac muscles and passes along with the iliopsoas muscle through the muscular hiatus out of the pelvis. It then innervates the iliopsoas muscle inside the pelvis and the femoral muscles outside the pelvis.

•\ Obturator nerve (L2–L4): Descends along the medial border of the psoas major muscle and passes along with the obturator artery through the obturator canal out of the pelvis. It then innervates the adductor muscles.

Sacral Plexus Formed by the anterior branches of the L5–S3 spinal nerves. The largest branch is the sciatic nerve, which passes through the infrapiriform foramen out of the pelvis and innervates the internal obturator and piriformis muscles inside the pelvis and the lower thigh muscles outside the pelvis.

Pudendal plexus Formed by the anterior branches of the S2–S4 spinal nerves. The pudendal nerve,

the largest branch, runs parallel to the internal pudendal artery and innervates the external anal sphincter, urethral sphincter, and ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles, among others.

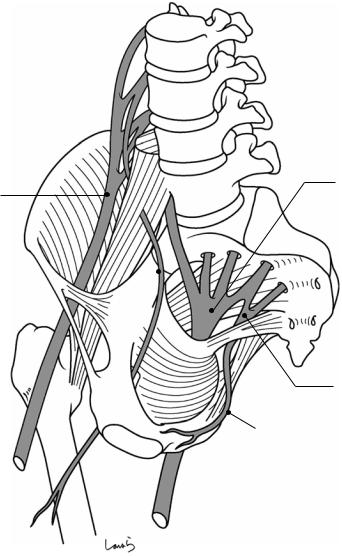

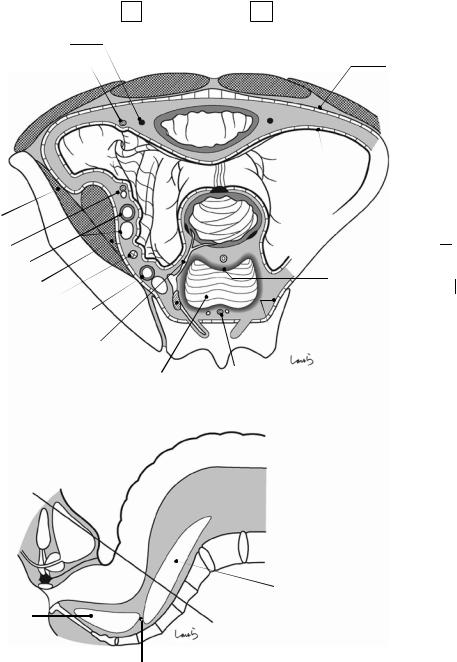

8.8\ Anatomy oftheNervous System (Autonomic Nervous System) (Fig. 8.8)

Sympathetic Nervous System

The nerve fibers extending anteriorly from the lumbar plexus of the bilateral sympathetic nerve trunks (lumbar splanchnic nerves) gather in front of the aorta and are vertically connected with each other to form the aortic plexus ( ). These plexuses are especially well developed at sites where the abdominal aorta gives off branches, referred to as the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric plexuses, respectively. Among these, the nerve bundle forming the inferior mesenteric plexus ( ) courses along the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) inside the mesocolon toward the sigmoid colon and the rectosigmoid (Rs).

The aortic plexus ( ), after passing through the aortic bifurcation, merges with the nerve fibers extending from the L2 and L3 lumbar splanchnic nerves in a triangular area bounded by the bilateral common iliac arteries and the promontorium (iliac triangle), forming the superior hypogastric plexus ( ). The nerve bundle then divides into the right and left hypogastric nerves ( ), which, while giving direct branches to the upper rectum (Ra), descend along the anterior surface of the sacrum medial to the internal iliac artery and eventually merge with the pelvic plexus ( ) (i.e., the inferior hypogastric plexus).

The lower part of the sympathetic nerve trunk descends medial to the anterior sacral foramen. This sacral plexus also gives off small branches (sacral splanchnic nerves) to the pelvic plexus.

Parasympathetic Nervous System

The pelvic splanchnic nerves ( ) arise as the innermost anterior branches of the S2–S5 sacral nerves and enters the pelvic plexus.

232 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

L1

Lumbar plexus |

L2 |

L3

Sacral plexus

Femoral n.

L5 |

|

S1 |

S2 |

Obturator n. |

|

S3 |

|

S4 |

|

|

||

|

|

Pudendal plexus

Pudendal n.

Sciatic n.

Fig. 8.7 Anatomy of the nervous system (somatic nervous system)

8.8 Anatomy of the Nervous System (Autonomic Nervous System) |

233 |

|

|

Lumbar splanchnic n.

Sympathetic trunk

Sup. hypogastric plexus

Hypogastric n. (R)  (sympathetic)

(sympathetic)

Sacral splanchnic n.  (sympathetic)

(sympathetic)

Pelvic splanchnic n. (parasympathetic)

Pelvic plexus

(sympathetic + parasympathetic) NVB

Corpus cavernosum

Sup. mesenteric plexus

Sup. mesenteric plexus

Aortic plexus

Aortic plexus

Inf. mesenteric plexus

Inf. mesenteric plexus

Sigmoid a.

Sup. rectal a.

Sup. rectal a.

Lateral lig.

Fig. 8.8 Anatomy of the nervous system (autonomic nervous system)

Pelvic Plexus

The pelvic plexus ( ) is a flat-shaped plexus formed from a combination of the hypogastric nerve ( ) (plus the sacral splanchnic nerve), a sympathetic nerve, and the pelvic splanchnic nerve ( ), a parasympathetic nerve. Damaging the hypogastric nerve causes ejaculatory dysfunction, while damaging the pelvic splanchnic nerve causes erectile dysfunction and impaired contraction of the urinary bladder and rectum, in short, bladder and bowel dysfunction.

Sensory nerve stimulation via stretch receptors elicited by distension of the bladder wall is also transmitted through the pelvic splanchnic nerves to the S2–S5 sacral ganglia, so damaging the pelvic plexus can cause complex disorders of urination, defecation, and sexual function.

From the pelvic plexus, visceral branches extend anteriorly to the bladder and prostate gland, intermediately to the uterus, and laterally to the rectum. These branches course along the

234 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

blood vessels branching from the internal iliac artery. The nerve fiber leading to the rectum is referred to as the “lateral ligament” and contains the middle rectal artery, which is in most cases small enough to be cauterized. The nerve fiber leading to the prostate gland is referred to as the “neurovascular bundle” (NVB). The NVB courses lateral to the prostate gland and, after giving off a branch to the prostate gland, reaches the spongy body of the penis where it controls erection. Even with efforts made to preserve the pelvic plexus, damaging any of the vesical branches or NVB results in loss of urination and erectile function.

8.9\ Structure oftheRetrorectal Space: Part I

Let us now explore the fascial anatomy, the main subject of this chapter. Computer tomographic (CT) cross sections of the descending colon (D), sigmoid colon (S), and rectosigmoid (RS) are shown in Fig. 8.9a, b, and c, respectively.

The mesentery is a fat fold that anchors the intestine to the abdominal wall and has a double- layered structure in which the peritoneum and the subperitoneal fascia surround its surface from both sides in an omega shape. The descending mesocolon merges with the abdominal wall after colliding with the posterior wall, while apposed peritoneal membranes are fused to become the fusion fascia of Toldt (Fig. 8.9a). Because the fusion fascia of Toldt ends near the external iliac artery, the sigmoid colon remains unanchored and regains its own mesentery, which, however, remains morphologically incomplete due to partial physiological adhesion of adjoining peritoneal membranes (Fig. 8.9b).

Below the fusion fascia of Toldt and the retroperitoneum physiologically adhered to the sigmoid mesocolon is the extraperitoneal fat, set apart by a small layer containing loose connective tissue. This fat layer provides paths for the gonadal artery and vein, ureter, plexuses, and periaortic lymph nodes. The inner and outer surfaces of the extraperitoneal fat are covered by

the subperitoneal fascia, which is a “sheet of thickened loose connective tissue.” Of these, the inner fascia (i.e., the fascia on the retroperitoneal side) is specifically referred to as the “subretroperitoneal fascia.” This is a broad fascia uninterruptedly lining the whole peritoneum and is locally referred to as the anterior layer of the renal fascia, also known as fascia of Gerota. The outer fascia (i.e., the fascia on the body surface side) is also a broad fascia and is specifically referred to as the “presacral fascia” in the posterior wall of the pelvis (it is discussed again in Fig. 8.12 on the end point of preand retrorectal dissection). The outer surface of the presacral fascia makes contact with the fascia transversalis, again set apart by a small layer containing loose connective tissue. Outside the fascia transversalis are abdominal muscles or bone.

Let us look now at Fig. 8.9c. The RS, continuing from the sigmoid colon, also has its mesentery, but differs from other parts of the colon because it is attached by a considerably wider base of the mesentery. This means that a sparse space is formed between the rectum and the sacrum. This is the “retrorectal space.” The formation of the retrorectal space is closely related to the “division of the aorta into the right and left iliac arteries” during the developmental process. While other mesenteries arise from the aorta as a double-layered peritoneal membrane like a partition, the mesorectum, which arises from the divided aorta, has its base separated into right and left. Also, the superior rectal artery (SRA), the main supplying vessel of the rectum, is not happy accompanying the iliac artery and immediately diverges from the aorta and then comes close to the rectum while descending along the midline. This results in reduced fat density of the mesorectal base, and a “space” is formed that contains loose connective tissue. This is how the retrorectal space is formed. The hypogastric nerve left behind by the SRA has no choice but to split into two, descending medial to the iliac artery while giving off several small branches to the rectum and finally forming the lateral ligament with the middle rectal artery branching from the internal iliac artery before reaching the

8.9 Structure of the Retrorectal Space: Part I |

235 |

|

|

a (D) |

R |

|

L |

|

|

||

|

|

IMA |

LCA |

Inf. mesentericplexus |

|

|

|

|

IVC |

Ao |

|

|

|

|

b (S)

Upper border of |

Sigmoid a. |

retrorectal space |

|

Sup. hypogastric plexus |

|

R common iliac a. |

|

Gonadal a. & v. |

|

IVC |

|

Ureter |

|

Med. sacral a. |

L common iliac a. |

c (RS)

Fusion fascia of Toldt

Marginal a.

Peritoneum

Peritoneum

Fascia transversalis

Fascia transversalis

Fascia of Gerota

Subperitonial fascia

Extraperitonealfat

Muscle

Physiological adhesion of sigmoid mesocolon

|

Rectal branches of hypogastric n. |

|

SRA |

Retrorectalspace |

L hypogastric n. |

R hypogastric n. |

|

L common iliac a.

L common iliac v.

Pre-sacral fascia

Med. sacral a.

Fig. 8.9 Structure of the retrorectal space: Part I

236 8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures

IMA |

Sup. hypogastric plexus |

|

|

Rectum |

|

SRA |

|

R hypogastric n.

Upper border of retrorectal space

R common iliac a.

Retrorectal space |

|

L common iliac a. |

|

|

|

(loose connective tissue) |

|

L hypogastric n. |

|

Med. sacral a. |

|

|

|

Fig. 8.9 (continued)

rectum. On the dorsal side of the retrorectal space is an artery descending straight from the bifurcation of the right and left iliac arteries, namely, the median sacral artery. The upper border of the retrorectal space appears to be located around the iliac triangle where the division of the aorta occurs, but it cannot be clearly defined because the space is essentially a loose connective tissue (the space itself can be found more cranially around the root of the IMA where the SRA diverges from the aorta and gradually expands distally). To be honest, there is not actually a space in the body that can be referred to as the retrorectal “space.” This is an artificially formed space created by the entrance of air (which can be CO2 in the case of laparoscopic surgery) when the surgeon lifts the RS and incises the peritoneum; it is morphologically distinct from the omental bursa or the infracardiac bursa (see Fig. 5.12), both of which are lined with the serous membrane and maintain a “cavity” structure.

Figure 8.9c shows the three-dimensionally constructed upper border of the retrorectal space

in the iliac triangle. The SRA arises considerably cranial to the bifurcation of the iliac arteries and descends along the ridge of the retrorectal space inside the fat tissue behind the rectum. The hypogastric nerve divides into right and left at a level lower than the bifurcation of the iliac arteries and descends medial to the internal iliac artery toward the pelvic plexus. The upper border of the retrorectal space is located around this division point, that is, around the superior hypogastric plexus. The hypogastric nerve courses very close to the retrorectal space. When entering the retrorectal space during surgery, the surgeon must always identify this nerve to avoid damaging it.

8.10\ Structure oftheRetrorectal Space: Part II

Now let us look at the Ra. Rather than the “lookup” view shown in Fig. 8.9a–c, Fig. 8.10a shows the “look-down” view, the same view that the surgeon has, of a cross section at the level of the

8.10 Structure of the Retrorectal Space: Part II |

237 |

|

|

a |

L |

(Ra, look-down view)

Lateral umbilical ligament (medial umbilical fold)

Inf. epigastric a (lateral umbilical fold)

Bladder

Vas deferens

Iliacusm. |

|

Gonadal a. & v. |

|

Ext. iliac a. & v. |

|

Psoas m. |

R |

Ureter |

|

Int. iliac a. & v. |

|

Rectal branch |

|

Hypogastric n. |

|

|

Retrorectal space |

b

(Ra, cross-section)

R

Fascia transversalis

Retroperitoneum

Subperitoneal fascia

Subperitoneal fascia

SRA

Fascia propria of rectum

Pre-hypogastric n. fascia

Pre-hypogastric n. fascia

Pre-sacral fascia

Med. sacral a.

L5 L4

S1

2 |

Retrorectal space |

|

Supralevator space |

3 |

4

5

Rectosacral fascia

Fig. 8.10 Structure of the retrorectal space: Part II

238 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

straight line shown in Fig. 8.10b. The spider web- like loose connective tissue covering the retrorectal space is gradually densified and replaced by the surrounding fat tissue (illustrated as a gradually darkened margin of the retrorectal space in Fig. 8.10a). This thickened zone is also termed “fascia.” The spider web threads, which are cut as if melted when the retrorectal space is entered, merge with this fascia.

When viewed from the inside of the retrorectal space (point R in Fig. 8.10a), the fascia lining the space is folded back along the right and left hypogastric nerves. This means that small nerve fibers extending from the hypogastric nerve to the rectum are forced to pass between the two fascias arising from both the abdominal cavity and sides of the retrorectal space forming the shape of the Chinese character “ .” Considering this as part of the basic mesenteric structure, it would be more natural to say that the mesorectum “divides into two parts from its base,” rather than that it “disappears” around the Ra.

The fascia lining the retrorectal space is thickest on the rectal side (the anterior wall when viewed from point R) and is accompanied by a thick fat layer between the retrorectal space and the rectum (including the SRA). This part of the fascia is referred to as the “fascia propria of the rectum.” The fascia lining the sacral side (posterior wall) of the retrorectal space appears to be identical to what is called the “parietal pelvic fascia” by Professor RJ Heald, who first described total mesorectal excision (TME) [13] and who named the fascia propria of the rectum the “visceral pelvic fascia.” In this book, we use the term “prehypogastric nerve fascia” [14] with the intention of warning surgeons to do the following: enter the retrorectal space while ensuring that the fascia anterior to the hypogastric nerve remains on the sacral side so as to spare the nerves.

Around the lower rectum (Rb), the fascia propria of the rectum extends toward the pelvic floor while lining the dorsal surface of a thick nerve bundle branching at a sharp angle from the pelvic

plexus, that is, the lateral ligament. Because this nerve bundle also allows for passage of the middle rectal artery (a branch of the internal iliac artery), the lateral ligament can be considered the last vessel group to be included in the bilaterally split mesorectal base.

Although in general the fascia propria of the rectum refers to the fascia surrounding the fat tissue on the dorsal side of the rectum, we should remember that this is the posterior layer and that the fascia continuing from the subretroperitoneal fascia and covering the anterior side of the rectum is the anterior layer. These two layers, which are interrupted by the right and left leaves of the mesorectum, merge beyond the lateral ligament where the mesorectal base discontinues, surrounding the Rb circumferentially (as illustrated in Fig. 8.15).

The rectum, which was once lifted from the body wall by the retrorectal space, again approaches the sacrum around S4, around which loose connective tissue again becomes denser. This loose connective tissue is recognized as a robust membranous structure forming a tent between the fascia propria of the rectum and the prehypogastric nerve fascia during surgery. This structure, which also serves as a suspender and anchors the lower rectum to the sacrum, is referred to as the “retrosacral fascia.” This used to be called “fascia of Waldeyer,” but this is not an appropriate name because the fascia that Waldeyer described appears to be part of the prehypogastric nerve fascia. Although some say that there is no rectosacral fascia, when we consider that the loose connective tissue on the posterior side of the rectum indeed becomes denser around S4 and that the “fascia” is essentially thickened connective tissue, it is more convenient to distinguish this fascia as the rectosacral fascia so that it can be used as a landmark for posterior dissection. This rectosacral fascia is generally recognized as the lower border of the retrorectal space; however, beyond the border continues a space containing loose connective tissue referred to as the “supralevator space” for a certain distance.