- •Foreword

- •Preface

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Prologue

- •1.9 Expansion of the Greater Omentum

- •3: Distal Gastrectomy

- •4: Total Gastrectomy

- •5.2 Part II: Thoracic Manipulation

- •6: Right Hemicolectomy

- •7: Appendectomy

- •8.6 Internal Pudendal Artery and Its Branches

- •8.13 Lateral Ligament

- •8.16 Fascia Propria of the Rectum: Part II

- •9: Sigmoidectomy

- •13: Hemorrhoidectomy

- •14: Right Hemihepatectomy

- •15: Left Lateral Sectionectomy

- •16: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- •17: Open Cholecystectomy

- •Bibliography

Appendectomy |

7 |

|

Abstract

Appendectomy, along with inguinal herniorrhaphy and hemorrhoidectomy, is a surgical procedure commonly performed by young gastrointestinal surgeons. However, appendicitis judged to require surgery in this era of advanced imaging technology tends to be accompanied by a certain amount of inflammation, complicating the surgical procedure. Recently, most cases of appendectomy are performed laparoscopically using a stapler, but this chapter illustrates conventional (open) appendectomy with standard operation time of 30 min.

Keywords

Appendectomy · Appendicitis · McBurney’s point

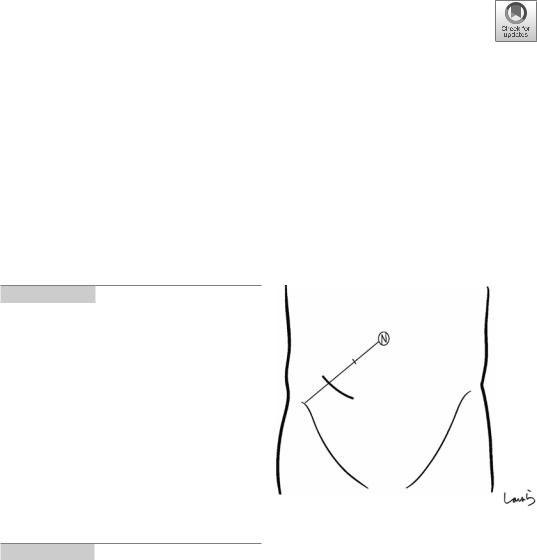

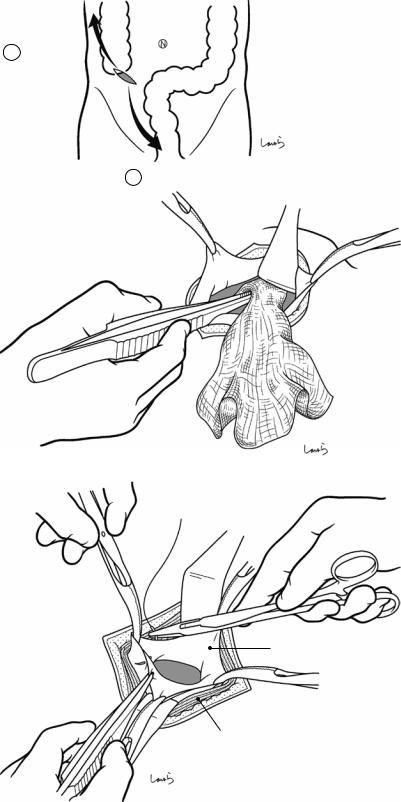

Fig. 7.1 An incision of about 5 cm is made (for adults) that passes a point at the lateral one-third of the line connecting the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine (McBurney’s point) and is along wrinkles in the skin. In patients with a broad and well-developed rectus abdominis muscle, making this incision too close to the midline may result in a transrectal incision, whereas making the incision too laterally may result in entering the retroperitoneum. It is advisable to place the incision about 1 cm laterally and 4 cm medially from McBurney’s point

A pararectal incision should be made instead if the skin incision may well need to be extended for ileocecal resection or other reasons

© Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 |

209 |

H. Shinohara, Illustrated Abdominal Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1796-9_7 |

|

210

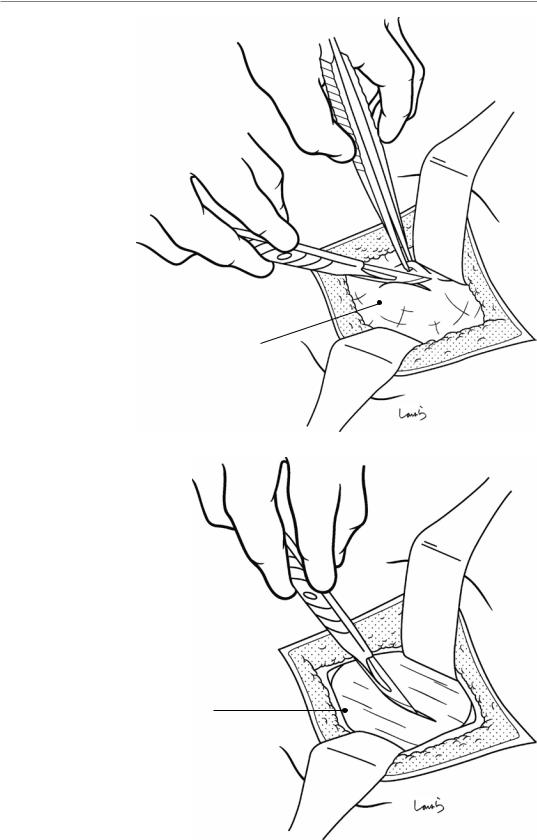

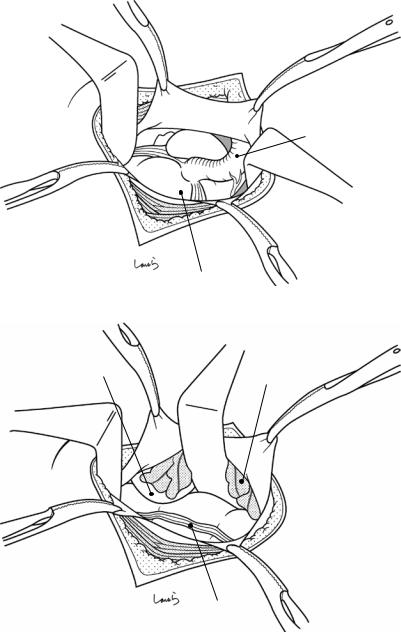

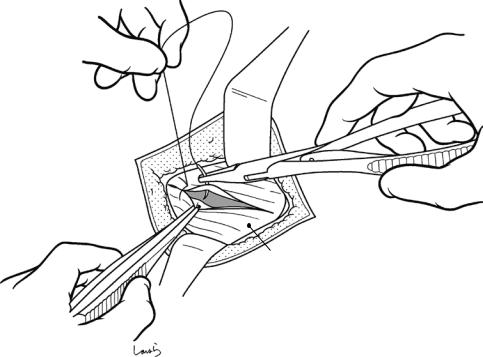

Fig. 7.2 The surgeon dissects the subcutaneous tissue and then incises two layers of superficial abdominal fascia using a scalpel and hooked forceps, while the first assistant expands the operative field using two flap retractors. Once the aponeurosis of the external oblique is reached, the first assistant again fully expands the wound in four directions with the retractors

Fig. 7.3 A small incision is made with a pointed blade on the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle along its fibers, and the wound margin is grasped with Pean forceps. The incision is extended vertically (along the fibers) with Mayo scissors. The first assistant applies a retractor to the subaponeurotic layer. In patients with a thick subcutaneous fat layer, the Pean forceps applied to the aponeurosis may be removed if interfering with subsequent procedures

Superficial fascia

Aponeurosis of ext. oblique m .

7 Appendectomy

7 Appendectomy

Fig. 7.4 The exposed internal oblique muscle is torn with the Pean forceps and opened vertically. The first assistant further expands the opening with the retractors

Fig. 7.5 The semilunar line (the boundary between the transversus abdominis fibers and the fascia) can now be identified. The muscle fibers lateral to the semilunar line are opened vertically and further expanded with retractors in the same way as described in Fig. 7.4. This way, the peritoneum is finally reached. The first assistant once again makes an effort to expand the wound in four directions with the retractors. Without this effort, the wound gradually becomes smaller compared with the skin incision

211

Aponeurosis of ext. oblique m .

Int. oblique m .

Peritoneum

Linea semilunaris

Transversus m.

212 |

7 Appendectomy |

|

|

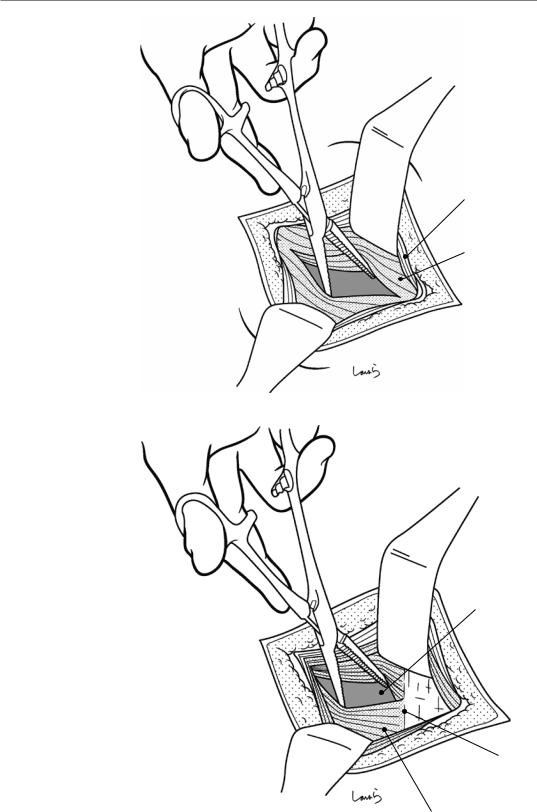

Fig. 7.6 The peritoneum is grasped and lifted with two pairs of hooked forceps and then incised with a round-edged knife. The margin of the incision is grasped with Mikulicz forceps

Peritoneum

Fig. 7.7 The peritoneum is incised vertically with Mayo scissors and the upper and lower margins of the incision are grasped with another two pairs of Mikulicz forceps (four pairs in all). The incision should be kept relatively small because excessively extending the peritoneal incision vertically makes it difficult to suture the incision closed later. Extending the incision beyond the fascia will not contribute to a wider view of the operative field

7 Appendectomy |

213 |

|

|

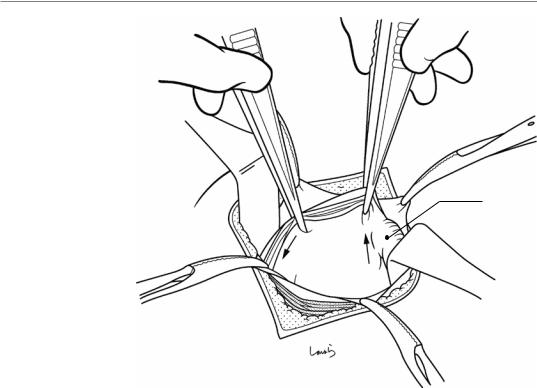

Fig. 7.8 The first assistant applies larger retractors to all layers of the abdominal wall to expand the operative field. If the appendix can be seen directly under the wound, the surgeon withdraws it with long

forceps, although having

such an operative field Appendix would be very lucky

Cecum

Fig. 7.9 If the greater |

|

omentum covers the |

|

operative field, the first |

|

assistant pushes the |

Small intestine |

greater omentum and |

Greater omentum |

|

|

small intestine medially |

|

with retractors to expose |

|

the cecum or ascending |

|

colon. Then, the tenia |

|

libera needs to be |

|

identified. The point of |

|

convergence of the three |

|

teniae coli, including the |

|

tenia libera, is the root |

|

of the appendix |

|

Teniae coli

214

Fig. 7.10 By tracing the teniae coli proximally with two pairs of long forceps, we reach the appendix. We can do this by repeatedly withdrawing the proximal cecum with the forceps held in the right hand and pushing the distal cecum back into the abdominal cavity with the forceps held in the left hand

7 Appendectomy

Appendix

7 Appendectomy |

215 |

|

|

a

Terminal Ileum

Inf. Ileocecal fold

Sup. Ileocecal fold

Appendix

b |

Appendicular a. (root) |

Ilecolic a.

|

|

|

Mesoappendix |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Appendicular a. |

|

|

|

|

|

Sup. IIeocecal fold |

|

|

Inf. IIecocecal fold |

|

|

|

(bloodless fold) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix |

||

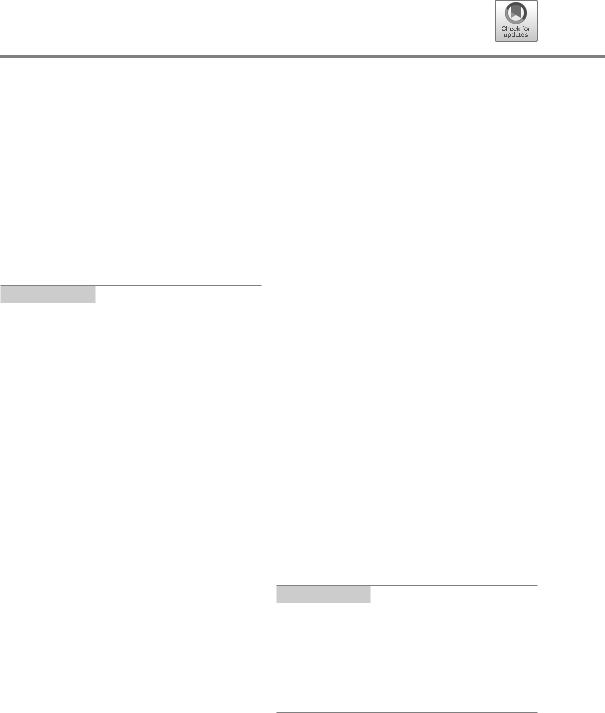

Fig. 7.11 Even if the first grasp is on the small bowel, tracing the bowel distally (or so believed) ends up reaching the transition to the cecum and the root of the appendix (a)

The mesoappendix, which includes the appendicular artery, passes behind the terminal ileum and is attached by fatty connective tissue in the shape of a right triangle on its anterior surface. This tissue is referred to as the fat triangle,

or more precisely as the inferior ileocecal fold, and it serves as a landmark for identifying the appendix (for this reason it is also referred to as “Merkmal fett”) (b). The inferior ileocecal fold is a membrane of fat that partially hangs down from the mesentery and covers the ileocecal junction

216 |

7 Appendectomy |

|

|

Adhesion

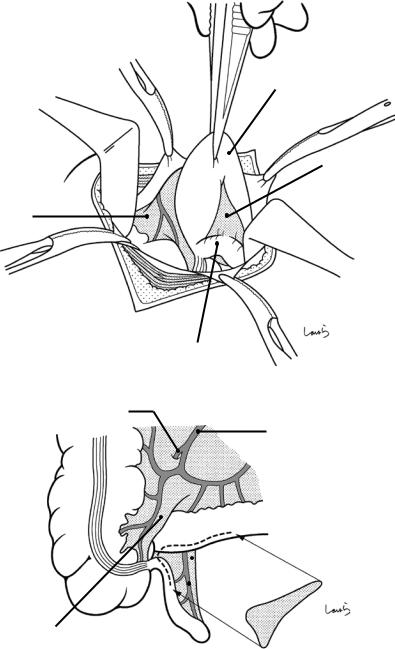

Fig. 7.12 It is not unusual for the tip of the appendix to be adherent to the abdominal wall due to severe inflammation and so not being able to be withdrawn immediately. In this case, we can pass a pair of dissection forceps through the mesentery around the root of the appendix to prevent the appendix from falling and then insert an index finger into

the wound to release the adhesions with the fingertip. The adhesions can be released in most cases in this way, although care is needed not to perforate the appendix by detaching it forcibly. If the adhesions cannot be released or the appendix is adherent to the cecum or other structure, we need a retrograde procedure to excise the appendix

7 Appendectomy |

217 |

|

|

Appendicular a.

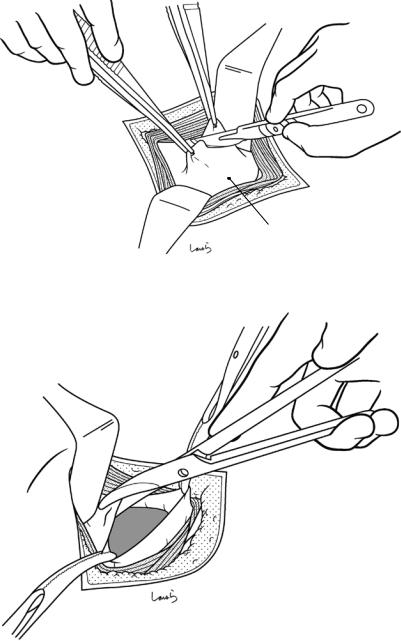

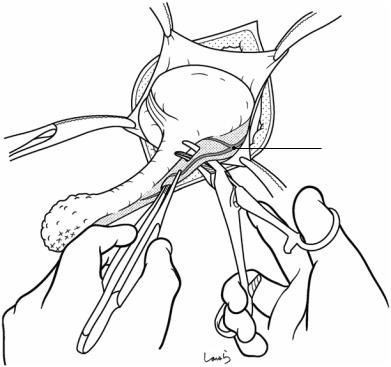

Fig. 7.13 Once the appendix has been withdrawn, it must be grasped firmly enough with forceps to prevent it from falling back into the abdominal cavity. A pair of dissection forceps is passed through the mesentery around the root of the appendix to scoop up the appendicular artery, followed by ligation and division of the artery. When there is severe mesenteric edema, we can do this by scooping the artery; although several attempts might be

needed, we should try to do this in one go by passing the forceps as close to the appendicular wall as possible. Failing to ligate the appendicular artery or, even worse, tearing it may cause the artery to fall into the abdominal cavity and then we have an uncontrollable situation on our hands. The vascular stump should be long enough to allow for reliable ligation. The resection side of the artery can be simply cauterized using electrocautery

218 |

7 Appendectomy |

|

|

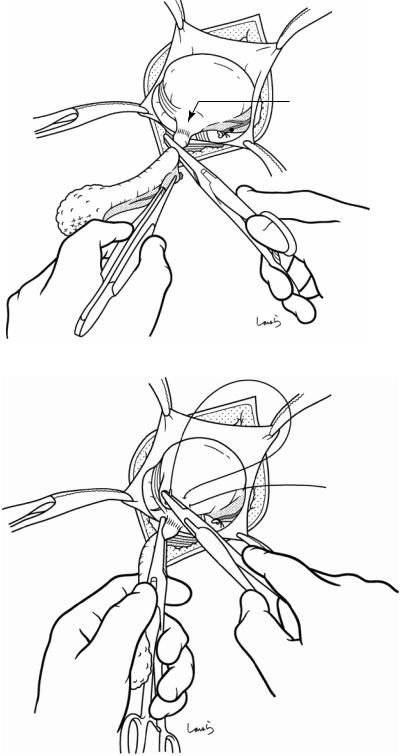

Fig. 7.14 The appendix is grasped using the forceps held with the left hand, and then a Kocher clamp, held with the right hand, is applied to the appendix several millimeters away from its root to crush that part. It is then displaced several millimeters distally to hold the appendix

Fig. 7.15 The Kocher clamp is then switched to the left hand and a 3-0 Vicryl purse-string suture is made using the right hand. Two points should be noted when making a purse-string suture: (1) making the suture too close to the root of the appendix can make it difficult to create a pocket to embed the stump, and (2) the suture should pass only through the seromuscular layer because a full-thick- ness suture may result in fecal fistula formation

Crushed part

Appendicular a. (cut)

Appendicular a. (cut)

3-0 Vicryl

7 Appendectomy |

219 |

|

|

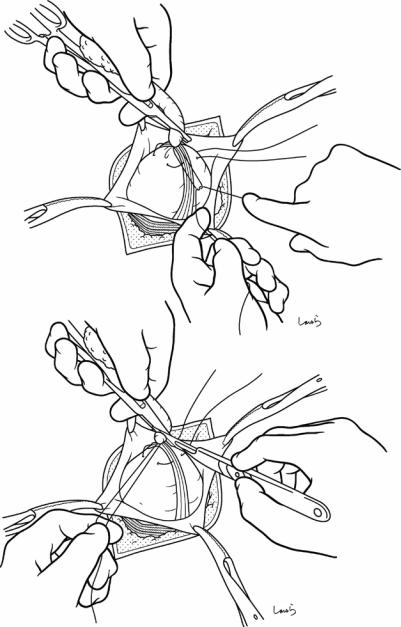

Fig. 7.16 With the first |

a |

assistant holding the |

|

Kocher clamp, the |

|

surgeon ligates the |

|

crushed part with a 1-0 |

|

Vicryl suture (a). |

|

Holding the suture |

|

thread with the left hand, |

|

the appendix is |

|

transected along the |

|

proximal side of the |

|

Kocher clamp using a |

|

pointed blade held with |

|

the right hand (b). The |

|

stump is disinfected |

|

with iodine |

|

b

3-0 Vicryl

1-0 Vicryl

220 |

7 Appendectomy |

|

|

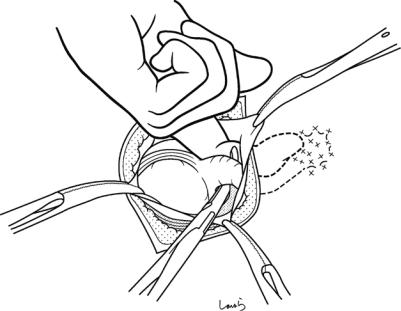

Fig. 7.17 The first assistant holds the suture thread on the appendicular stump and the surgeon grasps the cecal wall (lateral to the purse-string suture) with forceps held in the left hand. The surgeon cuts the suture thread on the stump with Cooper scissors held in the right hand. It is vital that the cecal wall is grasped when cutting the thread; otherwise, the cecum, which is no longer supported by any tissue, will slip back into the abdominal cavity

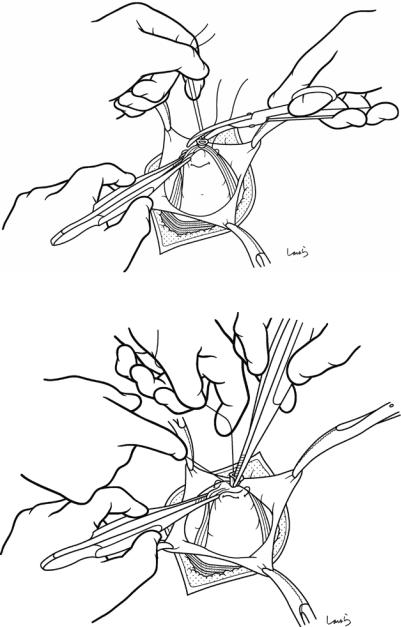

Fig. 7.18 The forceps |

3-0 Vicryl |

are switched to the right |

|

hand and one tip of the |

|

forceps is inserted into |

|

the appendicular stump |

|

to grasp it. Then, while |

|

the surgeon pushes the |

|

stump in, the first |

|

assistant tightens the |

|

preplaced purse-string |

|

suture. After confirming |

|

that the stump is fully |

|

embedded, the suture |

|

thread is cut and the |

|

cecum is placed back in |

|

the abdominal cavity |

|

7 Appendectomy |

221 |

|

|

Fig. 7.19 With long forceps, several pieces of gauze are inserted toward (1) the pouch of Douglas and (2) the lateral side of the colon to determine the nature of ascites (a). If pus is seen on the gauze, the sites should be wiped completely free of pus by repeating this procedure (b). Washing and drainage may be needed in cases of perforated appendicitis

Fig. 7.20 For abdominal closure, the peritoneum is closed using continuous 3-0 Vicryl sutures. With the excess of the same thread, one suture is made through the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles together

a

2R paracolic gutter

1 Pouch of Douglas

b

Peritoneum

Int. oblique m. + transversus m.

222 |

7 Appendectomy |

|

|

Aponeurosis of ext. oblique m.

Fig. 7.21 The aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is repaired with about 3 interrupted 1-0 Vicryl sutures. Finally, the skin is sutured closed to complete the operation

Anatomy of the Rectum |

8 |

and Surrounding Structures |

Abstract

Increased use of total mesorectal excision has led to increased discussion of the detailed fascial anatomy around the rectum. Several review articles that I have to hand give the impression that the pelvis is filled with a tediously large number of fascias. Is the fascial anatomy in the pelvis really that complicated that fascias need to be distinguished by so many different names? Reading these articles more closely and skeptically, it becomes clear that some membranes have multiple names, while other membranes are identified differently by different authors. So, we have a potentially confusing situation here.

A key objective in this book is to explain clearly what appears to be complicated. This begins in Chap. 1, on the anatomy of the stomach, by stating that the major principle of the mesentery applies not only to the rectum. And here, in the present chapter, this is continued by illustrating the anatomy of the rectum and surrounding structures based on the knowledge that the fascia of Gerota continues to the subretroperitoneal fascia and the fascia propria of the rectum continues to the prehypogastric nerve fascia and then to the rectosacral fascia, and that these two fascial systems are fused around the lower rectum to become the fascia propria of the rectum in a broad sense and circumferentially surround the rectum. Moreover, we view the fascia of Denonvillier as a connective tissue with the same structure as the fusion

fascia of Toldt, comprising a fused folded peritoneum. Also, we look at the “presacral fascia” (this eventually merges with the aforementioned systems) and another system consisting of the “fascia transversalis.” Ultimately, we find that we can clearly explain the anatomy of the rectum and surrounding structures without using other names while at the same time ensuring consistency with the anatomy of the stomach (Chaps. 1 and 2) and the inguinal canal (Chap. 19) and surrounding structures.

In this chapter, Sects. 8.1–8.8 describe the anatomy of the pelvic floor muscles, arteries, and nerves, and Sects. 8.9–8.16 focus on clarifying the fascial anatomy.

Keywords

Rectum · Mesentery · Total mesorectal excision · Pelvic fascial anatomy · Retrorectal space

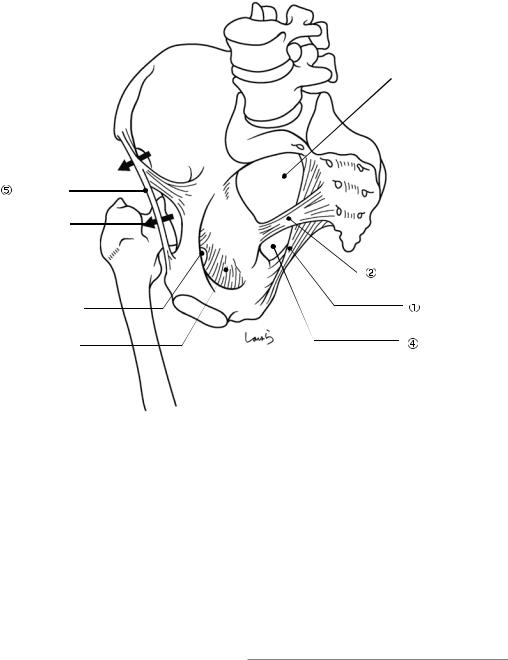

8.1\ Pelvis andLigaments

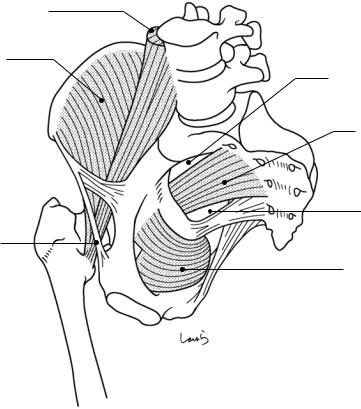

(Fig. 8.1)

Sacrotuberous ligament: Connects the ischial tuberosity to the posterior superior/inferior iliac spines, the sacrum, and the lateral margin of the coccyx.

© Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 |

223 |

H. Shinohara, Illustrated Abdominal Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1796-9_8 |

|

224 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

Greater sciatic foramen

Greater sciatic foramen

Muscular lacuna

Inguinal lig. |

|

Vascular lacuna |

|

|

Sacrospinous lig. |

Obturator canal |

Sacrotuberous lig. |

Obturator membrane |

Lesser sciatic |

|

foramen |

Fig. 8.1 Pelvis and ligaments

Sacrospinous ligament: Connects the ischial spine to the lower sacrum and the lateral margin of the coccyx.

Greater sciatic foramen: A foramen partitioned by the sacrospinous ligament and further divided into the following two compartments by the piriformis muscle that passes through it:

-1 Suprapiriform foramen: Allows for passage of the superior gluteal artery.

-2 Infrapiriform foramen: Allows for passage of the internal pudendal artery, pudendal nerve, and sciatic nerve.

Lesser sciatic foramen: A foramen bordered by the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments allowing for passage of the internal obturator muscle. The internal pudendal artery and the pudendal nerve, after passing through the infrapiriform foramen out of the pelvis, also pass through this foramen into the ischiorectal fossa (beneath the levator ani muscle).

Inguinal ligament: A ligament extending from the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The space bordered by this ligament and the superior pubic ramus is divided by the iliopectineal arch into the following two compartments:

-1 Vascular lacuna: Allows for passage of the femoral artery and vein.

-2 Muscular lacuna: Allows for passage of the iliopsoas muscle and the femoral nerve.

8.2\ Iliopsoas, Internal Obturator,

and Piriformis Muscles

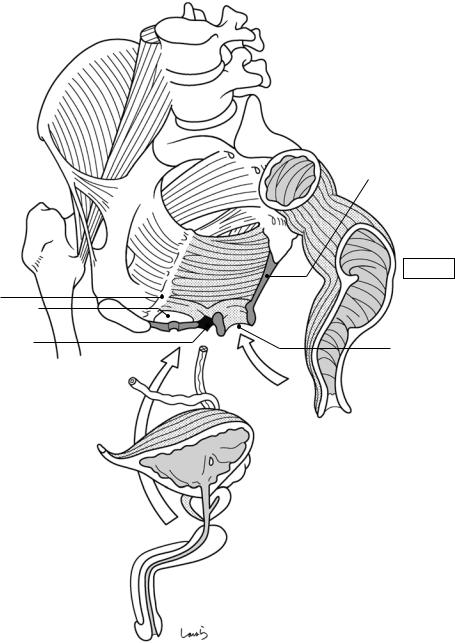

(Fig. 8.2)

Iliopsoas muscle: Composed of the iliac muscle, the psoas major muscle, and the psoas minor muscle. The iliac muscle originates from the entire surface of the iliac fossa on the inner aspect

8.3 Structure of the Pelvic Floor: Part I |

225 |

|

|

Psoas m.

Iliacus m.

Suprapiriform foramen

Piriformis m.

Piriformis m.

Infrapiriform foramen

Iliopsoas m.

Iliopsoas m.

Obturator intermus m.

Obturator intermus m.

Fig. 8.2 Iliopsoas, internal obturator, and piriformis muscles |

|

|

|

|

|

of the ilium, while the psoas major muscle origi- |

8.3\ |

Structure of the Pelvic Floor: |

nates from the lumbar vertebral bodies and trans- |

|

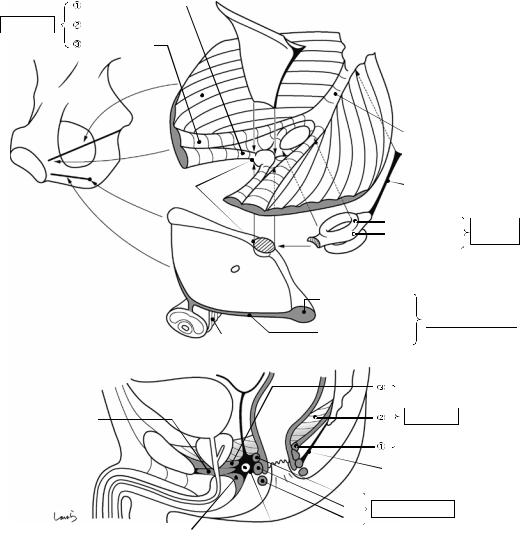

Part I (Fig. 8.3) |

verse processes. After merging, these muscles |

|

|

pass through the muscular lacuna under the |

The pelvic floor consists of two layers: the upper |

|

inguinal ligament out of the pelvis and attach to |

layer formed by the levator ani muscle and |

|

the lesser trochanter of the femur. |

the lower layer formed by the urogenital |

|

Internal obturator muscle: Originates from |

diaphragm. |

|

the obturator membrane and the surrounding area |

The levator ani muscle is a pair of bilateral |

|

on the inner side of the pelvis, turns in a right |

muscle bundles that originate from the pubis |

|

angle on the edge of the lesser sciatic foramen as |

and the tendinous arch of the levator ani mus- |

|

a pulley, passes through the lesser sciatic fora- |

cle (thickening of the internal obturator fascia |

|

men out of the pelvis, and attaches to the trochan- |

that connects the pubis and the ischial spine) |

|

teric fossa of the femur. |

and merge in the midline to form a reverse |

|

Piriformis muscle: Originates from the |

dome. Formed during this process are the uro- |

|

anterior surface of the sacrum between the sec- |

genital hiatus and the anal hiatus, which allow |

|

ond and fourth sacral foramina, passes through |

for passage of the urethra (and the vagina in |

|

the greater sciatic foramen out of the pelvis, and |

women) and the rectum, respectively. Between |

|

attaches to the greater trochanter of the femur. |

the |

anal hiatus and the coccyx is a thick |

226 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

Tendinous arch of levatorani m.

Urogenital hiatus

Perineal body

Vas deferens |

Ureter |

Bladder

Seminal vesicle

Prostate

Corpus spongiosum

Corpus cavemosum

Fig. 8.3 Structure of the pelvic floor: Part I

Anococcygeal body

Rectum

Anal hiatus

8.4 Structure of the Pelvic Floor: Part II |

227 |

|

|

ligament referred to as the “anococcygeal body,” which provides the tendon of insertion for the levator ani muscle bundle. This serves as a beam that supports the pelvic floor along with the perineal body, as discussed in the following section.

8.4\ Structure of the Pelvic Floor:

Part II (Fig. 8.4)

Let us look at the anatomy of the pelvic floor more closely. Between the urogenital hiatus and the anal hiatus, or at the apex of the reverse dome, is a lump of fibrous connective tissue as big as the tip of the thumb (basically a hard lump) that is referred to as the perineal tendon center or “perineal body.” This is literally “the center of the perineum” that supports the many parts that constitute the pelvic floor from below.

The levator ani muscle consists of three parts:puborectalis, iliococcygeus, and pubococcygeus muscles. The puborectalis muscle ( ) originates from the pubis, passes through the perineal body, and then turns around the rectum to form a loop while lifting it up anteriorly. The iliococcygeus muscle ( ), which constitutes the major part of the levator ani muscle, originates from the tendinous arch of the levator ani muscle and, while in contact with the lateral aspect of the puborectalis muscle ( ), inserts to the coccyx and the anococcygeal body. The reverse Y-shaped pubococcygeus muscle ( ), which is located most

superficially when viewed from the abdominal cavity, extends from the pubis over the puborectalis ( ) and iliococcygeus ( ) muscles to the coccyx.

The external anal sphincter is located below and in contact with the levator ani muscle and surrounds the anal canal in a circular manner. It can be divided into the deep (I), superficial (II), and subcutaneous (III) parts. The deep part (I) is ring-shaped and is fused with the puborectalis muscle fibers. The superficial part (II) is an anteroposteriorly elongated spindle shape and attaches to the perineal body anteriorly and to the anococcygeal raphe posteriorly. The subcutaneous part (III) is located subcutaneously along the anal verge and slightly apart from the deep (I) and superficial (II) parts. It is also separated from the internal anal sphincter (thickened inner circular muscle) by the conjoined longitudinal muscle fibers continuing from the outer longitudinal muscle of the rectum (Fig. 8.6b).

The anterior half of the pelvic floor is reinforced from below by the urogenital diaphragm composed mainly of the deep transverse perineal muscle. The superficial transverse perineal muscle, located along the posterior margin of the diaphragm, serves as a suspender to suspend the perineal body from the ischial tuberosity. The superior and inferior aspects of the perineal body are attached by the fascia of Denonvilliers, which will be described in Fig. 8.11, and by the bulbospongiosus muscle, which supports the penis, respectively. This is why this structure is called the perineal tendon “center.”

228 |

8 Anatomy of the Rectum and Surrounding Structures |

|

|

a

|

|

Puborectalis |

Levator ani |

|

Iliococcygeus |

|

|

Pubococcy |

|

|

arch |

|

tendinous |

|

|

|

. |

|

|

m |

|

To |

levator |

|

of |

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

To pubis |

|

|

To |

|

Perineal body |

|

|

|

|

||

To |

|

ischial |

tuberosity |

|

inf |

|

|

||

|

. |

|

|

|

|

pubic |

|

|

|

|

|

ramu |

||

b

Deep transverse perineal m.

Fascia |

|

Coccyx |

Denonvillier |

|

|

|

of |

|

|

s |

|

|

Anococcygeal body |

||

|

Anococcygeal raphe |

||

I |

Deep |

Ext. anal |

|

II |

Superficial |

||

sphincter |

|||

|

|

||

III Subcutaneous

III Subcutaneous

To perineal body

Urethra

Superf. transverse

perineal m.

Urogenital diaphragm

Bulbospongiosus m. |

Deep transverse |

perineal m. |

Levator ani

Anococcygeal raphe

I

II Ext. anal sphincter

III

Bulbospongiosus m. |

Perineal body |

Superficial transverse perineal m.

Fig. 8.4 Structure of the pelvic floor: Part II