- •Foreword

- •Preface

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Prologue

- •1.9 Expansion of the Greater Omentum

- •3: Distal Gastrectomy

- •4: Total Gastrectomy

- •5.2 Part II: Thoracic Manipulation

- •6: Right Hemicolectomy

- •7: Appendectomy

- •8.6 Internal Pudendal Artery and Its Branches

- •8.13 Lateral Ligament

- •8.16 Fascia Propria of the Rectum: Part II

- •9: Sigmoidectomy

- •13: Hemorrhoidectomy

- •14: Right Hemihepatectomy

- •15: Left Lateral Sectionectomy

- •16: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- •17: Open Cholecystectomy

- •Bibliography

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

16 |

|

Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which once formed the basis of endoscopic surgery, is a stereotypical procedure consisting of simply dissecting the cystic duct and cystic artery and then detaching the gallbladder from the liver bed. But it has some pitfalls, such as the risk of damaging the common bile duct and mis-

identifying the right hepatic artery. So, although it takes only about 40–50 min to complete the procedure, we must perform the procedure with due care.

Keywords

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy · Endoscopic surgery · Cystic duct · Cystic artery

© Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 |

399 |

H. Shinohara, Illustrated Abdominal Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1796-9_16 |

|

400 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

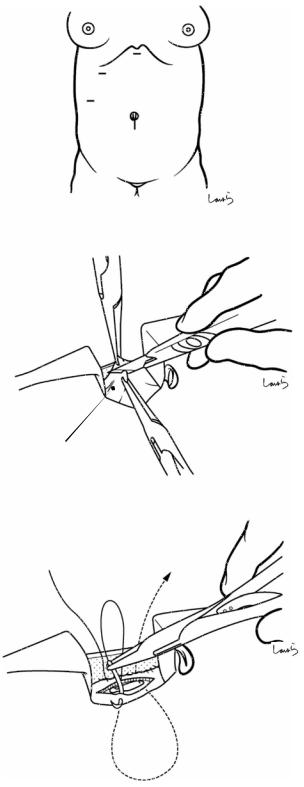

Fig. 16.1 The surgeon stands on the left side of the patient and makes a 2-cm skin incision below the umbilicus (a). After the second assistant exposes the anterior rectus sheath using two flat retractors, the sheath is grasped on both sides of the midline with Kocher clamps and lifted. A small incision is made on the anterior rectus sheath with a pointed blade and then extended vertically with Mayo scissors. After the flat retractors are repositioned into the rectus sheath to retract the rectus muscle bundle to the left, a small shallow incision is made on the posterior rectus sheath with a pointed blade (b). Finally, Pean forceps are inserted vertically to penetrate the peritoneum into the abdominal cavity. The little finger is inserted into the abdominal cavity to examine the area around the small laparotomy wound for any adhesions. A U-shaped 1 Vicryl suture is placed in the anterior sheath for wound closure and trocar fixation (c). The Kocher clamps are removed, and a 12-mm trocar is inserted as the first trocar ( in Fig. 16.2) and fixed with the Vicryl suture. The abdominal cavity is insufflated with carbon dioxide gas through the trocar

a

b

Ant. rectus sheath

c

1 Vicryl suture

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

401 |

|

|

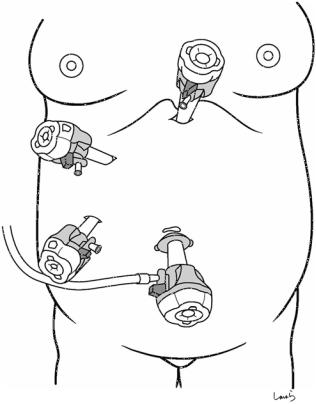

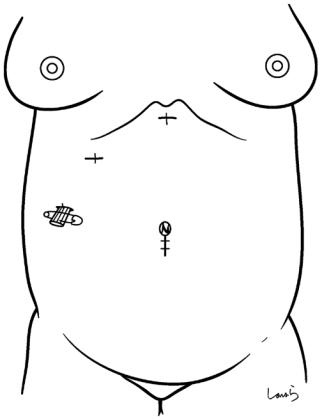

Fig. 16.2 Additional trocars are inserted in the epigastric region (12 mm, ), on the subcostal midclavicular line (5 mm,), and on the preaxillary line (5 mm, ). This should be done under guidance with a laparoscope inserted through trocar to avoid damaging the intestine. The surgeon uses trocars and and the first assistant uses trocar

12 mm

12 mm

5 mm

5 mm

5 mm

5 mm

12 mm

12 mm

402 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

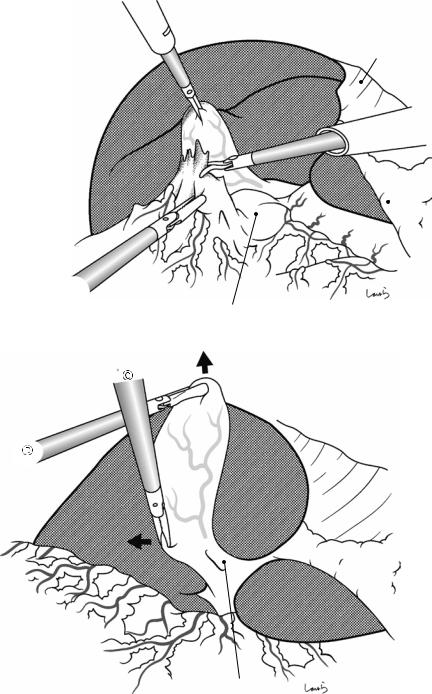

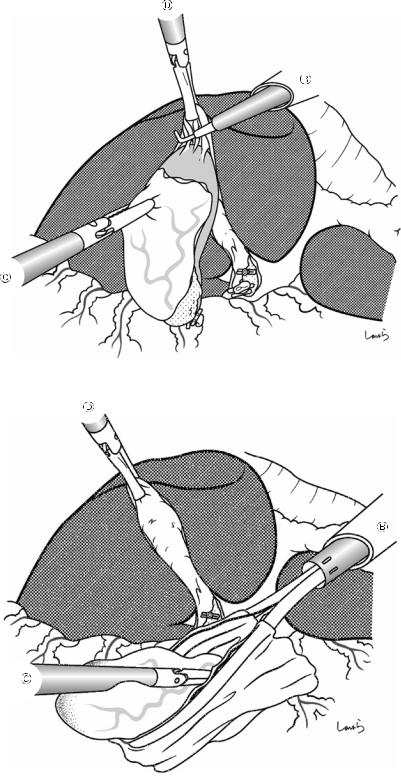

Fig. 16.3 The patient is positioned head-side up and left side down laterally to secure the operative field. Even with no prior history of inflammation, the gallbladder may have physiological adhesions to the greater omentum. In that case, the adhesions are released with scissors with intermittent electrical activation

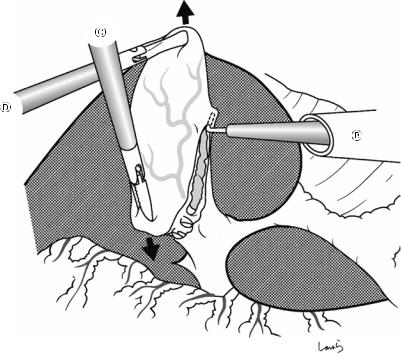

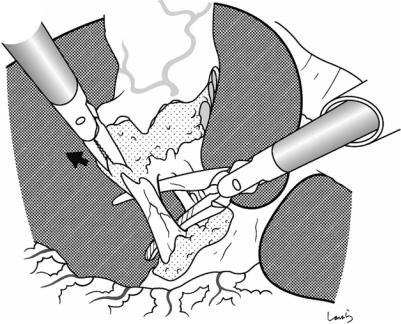

Fig. 16.4 Once ready for the operation, the first assistant grasps the fundus of the gallbladder with forceps inserted from trocar and lifts it cranially (back in the 12 o’clock direction on the screen). The surgeon grasps the pouch of Hartmann with the forceps held by the left hand through trocar and pulls it to the right (in the 9 o’clock direction on the screen) to expand the cystohe-

Falciform lig.

Ligamentum

teres

teres

Stomach

Duodenal bulbus

Triangle of Calot

patic triangle of Calot. If it is difficult to obtain a front view of the triangle of Calot, an oblique-viewing or flexible endoscope might help. If the triangle is hidden behind the colon or duodenum even when the fundus of the gallbladder is lifted, we can get a better view by the first assistant pushing the intestine dorsally with their forceps

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

403 |

|

|

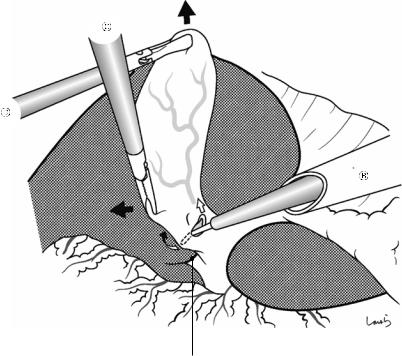

Sulcus of Rouviere

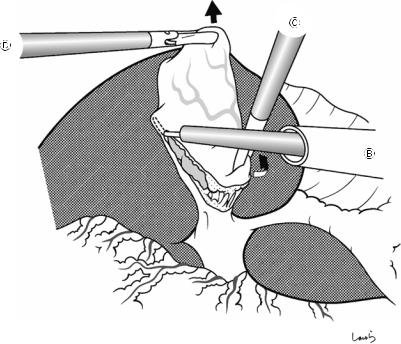

Fig. 16.5 With an L-hook dissector inserted from trocar, a U-shaped incision is made on the serosa of the triangle of Calot (small arrows). After the serosa is slightly cauterized with the tip of the hook to create an opening, the hook is slid through the opening under the serosa and the serosa is incised by electrically activating the dissector. We need to be sure that we make the U-shaped inci-

sion on the gallbladder side of the sulcus of Rouviere (a groove on the liver parenchyma through which the posterior segmental branch of the Glissonean pedicle enters) because placing the incision away from the gallbladder may result in us misidentifying the right hepatic artery for the cystic artery or damaging the right hepatic duct afterward

404 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

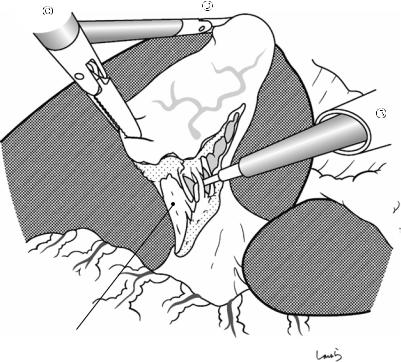

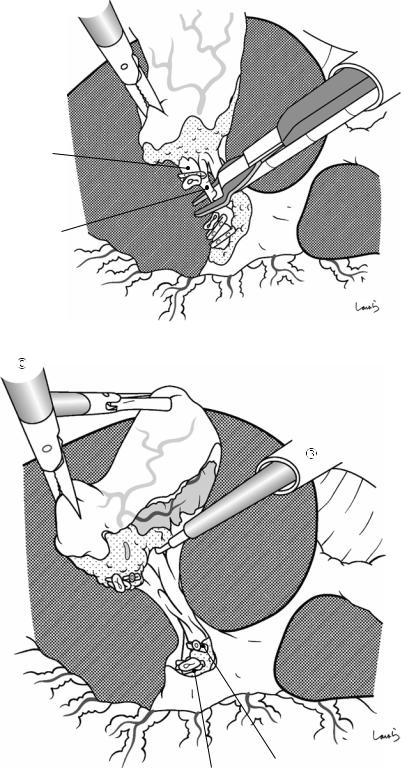

Fig. 16.6 The incision of the gallbladder serosa is extended by advancing the L-hook dissector along the ventral side of the attachment of the gallbladder to the liver toward the fundus. To avoid penetrating the gallbladder wall, the incision should be advanced by repeatedly sufficiently lifting only the serosa and dividing it by electrically activating the dissector. The grasping forceps

grasping the pouch of Hartmann held by the left hand are pulled caudally (in the 6 o’clock direction on the screen) to apply appropriate tension to the gallbladder serosa to be incised. Do not bring the incision line too close to the liver; keep a distance of about 5 mm from the liver. Stop the incision about 2 cm from the apex

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

405 |

|

|

Fig. 16.7 The serosal incision is also extended to the dorsal side of the attachment to the liver in the same way. With the grasping forceps held in the left hand, the pouch of Hartmann is twisted toward S4 (small arrow) to apply appropriate tension to the gallbladder serosa that is to be incised

406 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

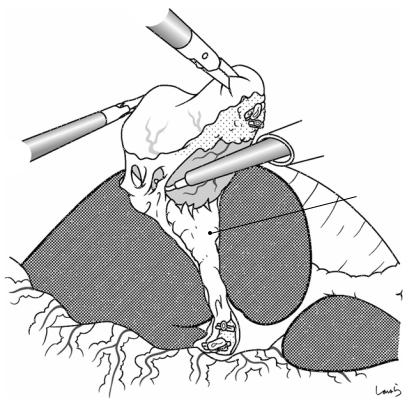

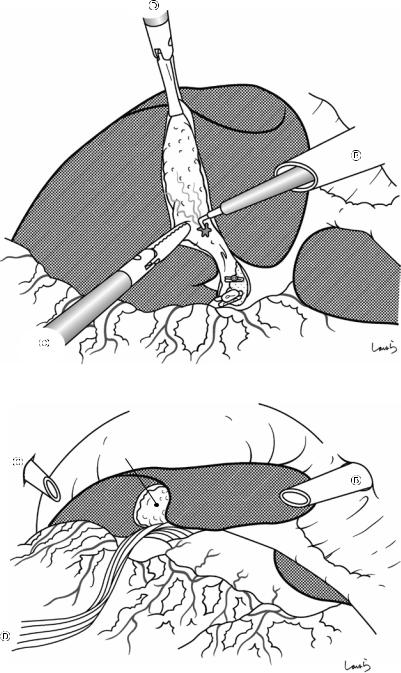

Fig. 16.8 We move now to detaching the cystic duct. The surgeon grasps the pouch of Hartmann with grasping forceps held by the left hand and pulls it to the right (in the 9 o’clock direction on the screen) to expand the triangle of Calot as much as possible. Next, the fat tissue around the cystic duct is scraped off toward the common bile duct with Maryland’s dissector . The fat tissue on the medial side of the cystic duct contains arteries and veins, so it is

advisable to advance the dissection from the lateral side because if bleeding occurs at this point, the triangle of Calot will be contaminated with blood, interrupting the flow of the operation. Once the lateral or anterior wall of the cystic duct is partially exposed, the dissection is stopped and resumed after confirming that the cystic duct is the correct one based on its positional relationship to the common bile duct and the common hepatic duct

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

407 |

|

|

Fig. 16.9 The thin |

|

fibrous tissue |

|

surrounding the cystic |

|

duct wall is most likely |

|

to be nerves. Forcibly |

|

pulling them apart with |

|

the Maryland’s dissector |

|

may cause bleeding, so |

|

they should be scooped |

|

with L-hook dissector |

|

and divided by |

|

electrically activating |

|

the dissector. The tissue |

|

should then be |

|

sufficiently lifted from |

|

the cystic duct wall |

|

before activating the |

|

L-hook dissector, to |

|

avoid thermal damage to |

|

the duct from the back |

|

of the dissector. After |

|

these fibrous tissues |

|

have been dissected, the |

|

cystic duct is further |

|

extended and its entire |

Cystic duct |

surface is exposed |

408 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

Fig. 16.10 To confirm |

|

that the cystic duct has |

|

been isolated |

|

circumferentially, |

|

Maryland’s dissector |

|

is advanced to penetrate |

|

through the recess |

|

formed medial to the |

|

duct. During this |

&\VWLF |

procedure, the pouch of |

GXFW |

Hartmann is grasped |

|

with grasping forceps |

|

held by the left hand and |

|

is pulled toward S4 of |

|

the liver to help |

|

dissector penetrate the |

|

connective tissue |

|

Fig. 16.11 If the connective tissue cannot be penetrated in one go, dissect the remaining tissue from the posterior side of the triangle of Calot to create an exit for the dissector

Cystic duct

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

409 |

|

|

Fig. 16.12 After advancing the dissector, its tip is opened along the long axis of the cystic duct to ensure a sufficient margin for transection. If this procedure causes an unexpectedly large amount of bleeding, we might have misidentified the common bile duct for the cystic duct

410 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

a

Sentinel gland

Cystic a.

Cystic duct

b

R hepatic a.

Triangle of Calot

Sentinel  gland

gland

Cystic a.

Cystic duct

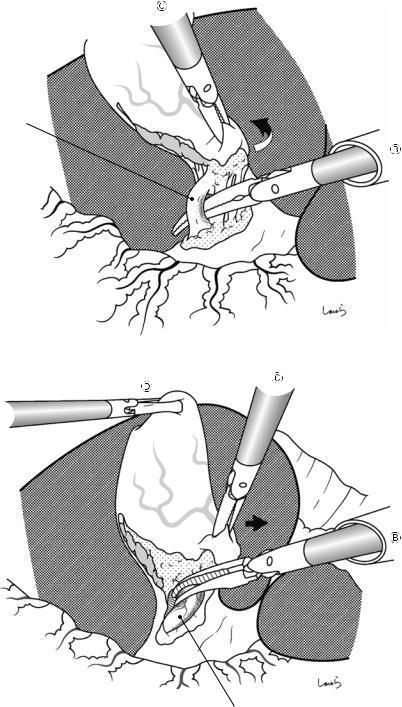

Fig. 16.13 Now the preparation for transecting the cystic duct is almost complete. To further ensure safety, the cystic artery should be identified before proceeding with the operation (a). The cystic artery typically branches from the right hepatic artery, which courses just medial to the neck of the gallbladder. Around the neck of the gallbladder is a lymph node referred to as the sentinel node, which can serve as a landmark for identifying the cystic artery because it usually courses under this lymph node (b)

As the residual fat tissue in the triangle of Calot is scraped off along the wall of the gallbladder neck toward

the bile duct, a cord-like structure containing the cystic artery is gradually exposed. However, if the dissection advances too far away from the gallbladder wall, we might have misidentified the right hepatic artery as the cystic artery. This risk is especially high when the branching point of the cystic artery from the right hepatic artery is at a higher level. So, be sure that the dissection proceeds along the neck wall. Once the cystic artery is identified, the dissector is then passed through the recess medial to the artery to reconfirm that the artery enters the gallbladder

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

411 |

|

|

|

|

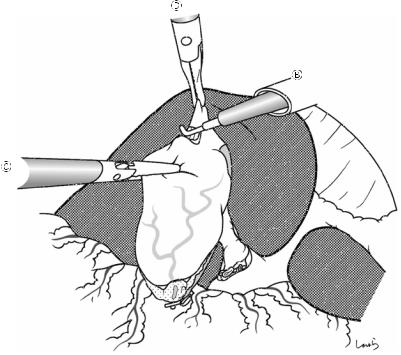

Fig. 16.14 Once we are |

a |

|

confident about having identified the vessels in the triangle of Calot, we can transect the cystic duct. One clip is applied on the cystic side and two clips on the common bile duct side (a), and the cystic duct is then divided with scissors (b)

b

412 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

Fig. 16.15 The cystic artery is then clipped and divided with scissors

Cystic duct (ligated)

Cystic a.

Fig. 16.16 Once the artery is cut off, the pouch of Hartmann is liberated from the triangle of Calot. The most critical part of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now done. The surgeon then pulls the pouch of Hartmann cranially (in the 12 o’clock direction on the screen) with the grasping forceps held in the left hand and gradually detaches the gallbladder from the liver bed with the L-hook dissector . Note that if the dissected cystic artery is thin, the main cystic artery may be hidden deep behind it, so the dissection should proceed carefully with this possibility in mind until the gallbladder neck is completely lifted from the liver bed

Cystic a. (root)

Cystic duct (confluence)

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

413 |

|

|

Liver bed

Fig. 16.17 The gallbladder should be detached from the liver bed by entering an appropriate layer so that the muscle layer of the gallbladder is exposed and the intervening connective tissue remains on the liver bed. When scooping the tissues with the L-hook dissector and dividing it using cauterization, the tissue should be sufficiently lifted from the gallbladder wall before electrically activating the

dissector—this avoids thermal damage to the wall from the back of the dissector and subsequent perforation. At the same time, we should be careful not to cut into the liver parenchyma, which may damage branches of the middle hepatic vein, resulting in massive bleeding and possibly requiring the switch to open surgery

414 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

Fig. 16.18 Although we can continue to complete the detachment from the neck to the fundus, it is also advisable to stop the procedure on the way and resume it from the fundus in the reverse direction to complete the detachment. The first assistant grasps the serosa and lifts up the gallbladder, accompanied by the liver, ventrally (in the

12 o’clock direction on the screen), while the surgeon pulls the fundus dorsally (in the 6 o’clock direction on the screen) with the grasping forceps held in the left hand. This applies countertraction to the serosa of the gallbladder in this area. The serosa is then incised with the back of the electrically activated L-hook dissector

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

415 |

|

|

Fig. 16.19 With appropriate tension applied continuously to the connective tissue remaining around the fundus, the back of the L-hook dissector is made to gently contact the connective tissue and is then activated to complete the dissection

Fig. 16.20 A specimen retrieval pouch is inserted through trocarto retrieve the gallbladder. The squeezed opening of the bag is grasped with the grasping forceps inserted through trocar. After the endoscope is switched from trocar

to trocar , another pair of grasping forceps is inserted through trocar

to receive the bag and extricate it from the body through the umbilical wound

416 |

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

|

|

Fig. 16.21 The abdominal cavity is again insufflated to confirm hemostasis of the liver bed. Mild bleeding, such as oozing, can be adequately treated by electrocautery with the L-hook dissector. Any bilious contamination occurring during the operation should be washed out

Fig. 16.22 If necessary, |

|

a Penrose drain tube is |

|

inserted through trocar |

|

and pulled out through |

Liver bed |

trocar . The tip of the |

|

tube is placed under the |

|

liver near the liver bed |

|

and the tube is fixed to |

|

the skin |

|

16 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy |

417 |

|

|

Fig. 16.23 The 1 Vicryl suture applied to the anterior rectus sheath around trocar wound is ligated to close the fascia and followed by skin suturing. The operation is completed by closing the remaining wounds with skin sutures