- •Russian Academy of Sciences

- •Read the text

- •Methodology

- •Conclusion

- •What makes a good summary?

- •Abstract

- •There are two kinds of abstract

- •Annotation writing

- •Sample descriptive annotation

- •Sample critical annotation

- •Annotated bibliography

- •Sample annotated bibliography entry

- •4.2. Writing Correspondence

- •Personal versus professional e-mail

- •Organizing an e-mail

- •Considering audience, purpose, and tone

- •Establishing a respectful tone

- •E-mailing a peer

- •E-mailing a scientist you do not know

- •Establishing the context of an e-mail

- •Managing e-mail

- •A full block format letter (from one person to another):

- •A modified block format letter (from one person to another):

- •A modified block format letter (from an organization to a person):

- •Your Address

- •The Date

- •Recipient’s Name and Address (inside address)

- •The salutation

- •The Subject

- •The Text of Your Letter (the body of the letter)

- •The Closing

- •Your Name and Signature

- •The 6th International Conference “Rivers of Siberia”

- •Participating in the discussion

- •Moderating the discussion

- •II. Conferences and symposia

- •III. ОСНОВЫ РЕФЕРИРОВАНИЯ И АННОТИРОВАНИЯ. ПРАКТИЧЕСКИЕ РЕКОМЕНДАЦИИ

- •Полезные фразы при анализе заголовка статьи:

- •Flat prospects

- •Digital media and globalization shake up an old industry (идея статьи)

- •A German company tries to deal with an unwanted endorsement (идея статьи)

- •Наречия и логические связки времени

- •Связки, вводящие новую информацию

- •Rendering of the article "Trouble at till"

- •English for Master's Degree and Postgraduate)

- •Grammar revision

- •Тренировочное упражнение

- •Тренировочное упражнение

- •Reading: читающий, читая

- •Тренировочное упражнение

- •Тренировочное упражнение

- •Переведите следующие словосочетания на русский язык:

- •§ 4. Глагол to be в сочетании с инфинитивом

- •Сложные формы герундия

- •Тренировочное упражнение

- •Укажите, в каких предложениях нужно употребить слово «который» при переводе их на русский язык.

- •§ 16. Инфинитивная конструкции «сложное подлежащее»

- •при сказуемом в действительном залоге

- •Глаголы, выражающие долженствование

- •§ 23. Предложения с вводящим словом «there»

Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Федеральное государственное бюджетное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования

«Хабаровская государственная академия экономики и права»

Н. И. Эмерель

ENGLISH

FOR ECONOMIC SCIENCE

Учебное пособие

Хабаровск 2012

2

ББК Ш 143.21 Х 12

English for economic science : учеб. пособие / сост. Н. И. Эмерель. – Хабаровск : РИЦ ХГАЭП, 2012. – 216 с.

Рецензенты : И. Г. Гирина, завкафедрой переводоведения и межкультурной коммуникации института лингвистики и межкультурной коммуникации ДВГГУ, канд. филолог. наук; Т. Н. Лобанова, доцент кафедры лингвистики и межкультурной

коммуникации ТОГУ, канд. пед. наук

Утверждено издательско-библиотечным советом в качестве учебного пособия

Учебное издание

Нина Израиловна Эмерель

ENGLISH

FOR ECONOMIC SCIENCE

Учебное пособие

Редактор Г.С. Одинцова

Подписано в печать |

Формат 60х84/16. |

Бумага писчая. |

Печать цифровая. Усл. п. л. 12,6.. Уч.-изд. л. 9,0.. |

Тираж 50 экз. |

|

Заказ № |

|

|

|

|

|

680042, Хабаровск, ул. Тихоокеанская, 134, ХГАЭП, РИЦ © Хабаровская государственная академия экономики и права, 2012

3

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Предлагаемое учебное пособие предназначено для лиц, обучающихся по программам послевузовского профессионального образования (отрасль науки 08.00.00 «Экономические науки»).

Целью пособия является развитие коммуникативных умений и навыков различных видов речевой деятельности, аннотирования и реферирования научной литературы, необходимых для эффективного общения в научной среде, а также для подготовки к сдаче кандидатского экзамена по английскому языку.

Пособие состоит из трёх частей. Первая часть ориентирована на развитие навыков: различных видов чтения, перевода и реферирования; научного письма (написание статей, докладов, тезисов) и ведения переписки;

общения в научной среде (высказывание по теме научного исследования, презентация научного доклада на конференции, участие в дискуссии).

Тематическая направленность пособия определена в соответствии с современными потребностями научного общения в следующих областях:

роль науки в развитии общества;

достижения науки в области научных интересов аспиранта в странах изучаемого языка; предмет научного исследования аспиранта;

система и социокультурные особенности подготовки аспиранта в стране и за рубежом; международное сотрудничество в научной сфере: международный научный семинар (конференция, конгресс, симпозиум, дискуссия).

Тексты научного и экономического содержания сопровождаются лексическими и грамматическими упражнениями и коммуникативными заданиями, направленными на развитие соответствующих навыков и умений.

Вторая часть включает дополнительный материал по соответствующим разделам первой части. Предлагаемый материал содержит комментарии и рекомендации на русском языке, а также дополнительные упражнения и задания, что делает возможным использование данного пособия для обучения слушателей с разной языковой подготовкой.

Третья часть пособия предназначена для обучающихся, испытывающих недостаток знаний по грамматике английского языка. В ней представлены основные разделы грамматики, которые в зависимости от уровня подготовки могут быть использованы для повторения, изучения и тренировки различных грамматических явлений.

Таким образом, пособие нацелено на совершенствование знаний грамматики и лексики, развитие навыков речевой деятельности и перевода, а также на развитие способностей логического мышления и эффективной переработки информации. Все эти знания и навыки позволят не только успешно сдать кандидатский экзамен, но и, несомненно, могут быть использованы для работы с иностранными источниками в процессе научного исследования с целью поиска и отбора необходимых сведений для написания научных статей и диссертации.

Данное пособие составлено на основании Рабочей программы дисциплины «Иностранный язык» для аспирантов и научных работников и в соответствии с федеральными государственными требованиями к структуре основной профессиональной образовательной программы послевузовского профессионального образования (аспирантура), утвержденными приказом Министерства образования и науки Российской Федерации.

4

Unit 1. LEARNING AND RESEARCH CENTERS.

Moscow State University

Read the text.

One of the oldest Russian institutions of higher education, Moscow University was established in 1755. In 1940 it was named after Academician Mikhail Lomonosov (1711 – 1765), an outstanding Russian scientist, who greatly contributed to the establishment of the university in Moscow.

Nowadays, as it has done throughout its history, the University retains its role of a major center of learning and research as well as an important cultural center. Its academics and students follow the long-standing traditions of the highest academic standards and democratic ideals.

In June 1992 the President of the Russian Federation issued a decree establishing the status of Moscow University as a self-governing institution of higher education. In November 1998, after a wide-ranging discussion, the Charter of Moscow University was approved. It proclaims Moscow University a self-governing body operating under its own Charter and the laws of the Russian Federation.

According to the Charter the Conference of academic councils makes decisions concerning operation of the University as a whole and elects its Rector. Current matters are discussed by the MSU Academic Council uniting Rector and ProRectors, Deans of the faculties, Directors of research institutes and centers, representatives elected by the faculties (both academics and students) and by the services. At its monthly meetings the Academic Council considers current academic and research agenda, approves changes in the University structure and its budget, grants academic titles and approves chair appointments, discusses plans for the University development.

Moscow State University is a major traditional educational institution in Russia; it offers training in almost all branches of modern science and humanities. Its undergraduates may choose one of 128 qualifications in its 39 faculties, while postgraduate students may specialize in 18 branches of science and humanities and in 168 different areas. The total number of MSU students exceeds 40,000; besides, about 10,000 high school students attend various clubs and courses at MSU. Various kinds of academic courses and research work are conducted at MSU Museums, affiliated subdivisions in various locations in Russia, on board scientific ships etc.

5

Studying at MSU

As training highly qualified specialists has always been the main goal, the faculties and departments constantly revise their curricula and introduce new programs. A number of faculties offer 4-year Bachelor’s and 2-year Master’s Degree programs, together with traditional 5-year Specialist Degree programs. Currently the stress is on student's ability to work independently and meet employer's requirements, thus practical experience in the field being of foremost importance.

The curricula of all MSU faculties are based on the combination of academic instruction with student's research work and the combination of thorough theoretical knowledge with specific skills. Having acquired theoretical knowledge in the first and the second year, in their third year undergraduates choose an area to specialize in. At the same time they choose a field for their independent study, joining elective special seminars; the results of research are usually presented at the meetings of students' scientific societies or at scientific conferences, the most interesting results are published.

Normally, a degree program at MSU takes from 4 to 6 years to complete. At the end of the final semester the results of each student's independent research are submitted in the form of final paper, which is publicly presented by the student at the meeting of the department.

The students in most MSU programs do not pay their tuition but 15% of students whose tuition is not covered by the government funding have to pay fees. Students whose academic performance is up to the standard receive grants. Accommodation in MSU dormitories is provided for those students who are not residents of Moscow.

According to the MSU Charter, The MSU Student Board is a form of student government, coordinating various aspects of campus life and activities. At the moment there are a number of various students’ public organizations at MSU.

MSU graduates work in institutes of higher learning, research institutes, in industry, governmental agencies, public organizations and private companies.

MSU has a long-standing tradition as a center of retraining admitting up to 5,000 various specialists a year, highly-qualified professionals updating themselves on the latest achievements in various fields of science and humanities.

Scientific Research

MSU is a center of research science famous for its major scientific schools. There have been 11 Nobel Prize winners among its professors and alumni, out of 18

6

Russians who have received the prestigious prize so far. Many more MSU scientists have been awarded various Soviet and Russian prizes for their achievements, among them 60 Lenin Prizes and 120 State Prizes, over 40 MSU scientists having received the State Prizes over the last decade.

Among those who teach and do research at MSU there are 2,500 higher doctoral degree holders and almost 6,000 holders of doctoral degrees, the total number of professors and instructors being about 5,000; there are over 300 full members and correspondent members of the Russian Academy of Sciences and other academics. About 4,500 scientists and scholars are currently involved in 350 research projects in various fields.

Besides its 39 faculties, Moscow University comprises 15 research institutes, 4 museums, 6 local branches in Russia and abroad, about 380 departments, the Science Park, the Botanical Gardens, The Library, the University Publishing House and a printing shop, a recreational center and a boarding school for talented children.

A number of new faculties, departments and research laboratories have been recently established, new academic programs are being continuously introduced together with new curricula; there are over 140 distance learning programs. Research has recently started in 30 new interdisciplinary areas.

The University's scientific potential creates a unique opportunity for interdisciplinary research and pioneering work in various branches of science. The recent years have been marked by achievements in the fields of high-energy physics, superconductivity, laser technology, mathematics and mechanics, renewable energy sources, biochemistry and biotechnology. New problems to be studied by scholars often reveal themselves while they are working on various aspects of sociology, economics, history, psychology, philosophy and the history of culture. On average 800 doctoral and 200 higher doctoral degrees in various fields of science and humanities are awarded at MSU every year.

Moscow University is a major innovative center. The first Russian Science Park appeared at MSU; in the last three years about 70 small companies have been founded within the Park, they specialize in chemistry and innovative materials, biotechnology, pharmaceutics, ecology and environmental management, production of scientific equipment and instruments. The Park unites about 2,000 scientists who work to make scientific achievements into technological innovations, cooperating with business companies in the development of innovative technologies. It is in the Scientific Park that the links with leading Russian companies and potential employers of University graduates are established.

7

MSU International Cooperation

MSU collaborates with the Eurasian University Association and has links with about 60 educational institutions, centers, unions, and universities in Europe, the USA, Japan, China and some other Asian countries, in Australia, Latin America, Arab countries. 5 MSU branch campuses have been opened in the former Soviet republics.

Since 1946, when the first international students were admitted, over 11,000 highly qualified specialists have been trained at MSU for 150 countries. Over 2,000 undergraduate and post-graduate students enroll every year, with over 400 students in the Russian / University intensive preparation programs.

Scientific and scholarly cooperation, academic and student exchange are part of university life. Receiving about 2,000 students and academics from abroad, the University sends out about the same number of its own professors, instructors and students to various countries all over the globe.

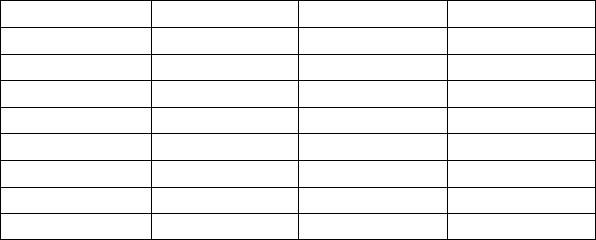

1. Complete the chart. Write the appropriate related words under each heading. If a word does not exist put X.

Nouns |

Verbs |

Adjectives |

Adverbs |

|

|

|

|

|

establish |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

academic |

|

|

|

|

|

scientist |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

educate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

decision |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

discuss |

|

|

|

|

|

|

operation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

completely |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

actively |

|

|

|

|

|

research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

graduate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

theoretical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

publicly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

special |

|

|

|

|

|

qualification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8

achieve

admit

election

develop

traditional

train

study

collaboration

doctor

2.Find in the text the sentences in which the words from the table are used. Translate them. Use these words in the sentences of your own.

3.Analyze the forms of the verbs given in italics (before you do this refer to the

Grammar Revision section).

4.Find Russian equivalents for the underlined words and phrases. Translate the text. Discuss the vocabulary. Pay attention to the similarities and differences in a scientist’s status in different countries. (For more related vocabulary refer to the text “Scientist’s status” in the Supplementary Material section).

5.Answer the questions.

1.When was MSU founded?

2.Who was it named after and why?

3.What is today’s status of the MSU?

4.How is the University operated?

5.What are the main activities of MSU?

6.How is the process of education organized?

7.What are the main goals of education at MSU?

8.What training programs are offered?

9.What is of the primary importance in the training process?

10.What are the curricula of all faculties based on?

11.How long does a degree program take?

12.What is the MSU research center famous for?

13.Who teaches and does research at MSU?

14.What is the technical base for scientific activity of MSU?

15.What are the results of innovative activity of the University?

16.How important is the international cooperation for the University?

9

5.Work in pairs. Talk about the universities you graduated from (or you are working at). Share with the class the information you got from your partner.

6.Speak about the university you graduated from.

Unit 2. RESEARCH WORK ORGANIZATION IN RUSSIA

Read the text.

Many post-Soviet countries, including Russian Federation, have a two-stage research degree obtaining path, generally similar to the doctorate system in Europe. The first stage is named "Kandidat (Кандидат наук) of <...> Sciences" (literal translation means "Candidate of Sciences", for instance, Kandidat of Medical Sciences, of Chemical Sciences, of Philological Sciences, and so on). The Kandidat of Sciences degree is usually recognized as an equivalent of Philosophy Doctor (Ph.D.) degree and requires at least (and typically more than) three, four or five years of postgraduate research which is finished by defense of Dissertation or rarely - thesis. Additionally, a seeker of the degree has to pass three examinations (a so-called "Kandidat's minimum"): in his/her special field, in a foreign language, and in the history and philosophy of science. After additional certification by the corresponding experts, the Kandidat degree may be recognized internationally as an equivalent of Ph.D. (An unconditional Ph.D. equivalence has been recognized before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the additional certification in many countries has become required after the steep increase flow of post-Soviet emigration). The second stage is Doktor nauk, "Doctor of <...> Sciences". It requires many years of research experience and writing of a second dissertation. The degrees of Kandidat and Doktor of Sciences are only awarded by the special governmental agency (Higher Attestation Commission); a university or a scientific institute where the thesis was defended can only recommend awarding a seeker the sought degree.

The work on a dissertation is commonly carried out during a postgraduate study period called aspirantura. It is performed either within an educational institution (such as a university) or a scientific research institution (such as an institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences network). It can also be carried out without a direct connection to the academy. In exceptional cases, the Kandidat Nauk degree may be awarded on the basis of published scholarly works without writing the thesis. In experimental sciences the dissertation is based on an independent research project conducted under the supervision of a professor, the results of which must be published in at least three papers in peer-review scientific journals.

10

A necessary prerequisite is taking courses in philosophy, foreign language and History and philosophy of science, and passing a qualifying examination called “candidate minimum”. The dissertation is presented (defended) at the accredited educational or scientific institutions before a committee called the Scientific Council. The Council consists of about 20 members, who are the leading specialists (including the academicians) in the field of the dissertation and who have been selected and approved to serve on the Council. The summary of the dissertation must be published before public defense in the form of "autoreferat" in about 150-200 copies, and distributed to major research organizations and libraries. The seeker of the degree must have an official "research supervisor (advisor)". The dissertation must be delivered together with official references of several reviewers, called "opponents". In a procedure called the "defense of the dissertation" the dissertation is summarized before the Commission, followed by speeches by the opponents or the reading of their references, and replies to the comments of the opponents and questions of the Commission members by the aspirant.

If the defense is successful (66.6% majority of votes by the secret ballot voting by the members of the Council), it is recommended and later must be approved by the central state-wide board called Higher Attestation Commission or "Vysshaya attestacionnaya komissiya" or VAK.

1. Give English equivalents of the following:

получить степень, кандидат наук, признавать научную степень, исследование на соискание учёной степени, соискатель учёной степени защита диссертации, кандидатский минимум, проводить исследование, аспирантура, научное учреждение, научная работа, самостоятельное исследование, научный руководитель, рецензируемый научный журнал, необходимое условие, аккредитованное образовательное или научное учреждение, учёный совет, член учёного совета, ведущий специалист, автореферат, рецензент, отзыв на диссертацию, тайное голосование, утверждать в ВАКе.

2.Find Participles in the text and analyze their functions. Translate the sentences where they are used. (Refer to the Grammar Revision section).

3.Analyze modal verbs used in the text. (Refer to the Grammar Revision section).

4.Translate the text.

11

Russian Academy of Sciences

Read the text

1)The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) was founded in Saint Petersburg on the order of Peter the Great and by Decree of the Senate of January 28 (February 8 - by Julian calendar), 1774. The Academy immediately responded to the demands of the times through its scientific research and publications, and quite soon achieved scientific results that were at par with those of other European institutions. The traditions and scientific schools established and further developed by the Academy, as well as its world excellence of research in basic and applied science naturally merited the status of the top scientific institution of the country. Between 1925 and 1991 the Academy bore the name that incorporated the name of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics – the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. It was reconstituted as the Russian Academy of Sciences on November 21, 1991 by a decree of the President of the Russian Federation that also confirmed its status as the highest scientific institution in Russia.

2)To a considerable extent the Academy's history is also the history of Russian science and the formation of a national scientific community. It is a chronicle of the major discoveries and inventions in all fields of knowledge. It envelops the creation of the national system of education, the mastering and development of the productive forces of Russia, the strengthening of the defense potential and national security of the country, and finally, it shows a sizable contribution made by the Academy to the national material, spiritual and intellectual culture of Russia and to world science as well. Nowadays within the Russian Federation, the Russian Academy of Sciences maintains and develops cooperation in science and technology with industrial scientific institutions, large manufacturing establishments and corporations, higher education institutions and universities, as well as with other Academies of the Russian Federation (the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the Russian Academy of Education, the Russian Academy of Architecture and Building Sciences, and the Russian Academy of Arts).

3)The Academy also maintains permanent relations with State and Government authorities – the legislative and the executive branches of power in the Russian Federation. RAS contributes significantly to the elaboration of the acts of legislation at the Federal level. The Law "On Science and the State Scientific and Technical Policy" and the 4th Part of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, the latter incorporating inter alia the intellectual property rights, are just good examples for the illustration of

12

this important part of the Academy's activity. RAS participates on a permanent basis on the Council for Science, Technology and Education under the Chairmanship of the President of Russia with the President of the Academy being Vice-Chair of the Council. Very often the Russian Academy of Sciences is made responsible for preparation of expert materials for the meetings of the Security Council of the Russian Federation. Indeed, according to Paragraph 8 of the Statutes of RAS, every year before July 1 the Russian Academy of Sciences presents to the President and to the Government of the Russian Federation the following documents: a) Reports on the state of basic and applied science in the Russian Federation and on the most important research achievements made by the Russian scientists; b) Reports on scientific and organizational activity and on finances and administrative activity of RAS; and c) Proposals for priorities along the basic and the applied branches of science and for research of a pioneering nature as well.

4)The primary objective of the Academy is to organize and conduct basic research, to get new knowledge about the laws of nature, society and man, which would facilitate the technological, economic, social and spiritual development of Russia. In its current activity the Academy is guided by the following main aims: a) to provide all possible assistance to the development of science in Russia; b) to strengthen the ties between science and education; and c) to enhance the prestige of knowledge and science, and the status and social protection of scientists. The Statutes of RAS is the principal document that regulates the activity of the Academy. The latest version of the Statutes was approved by the Government of the Russian Federation on November 19, 2007. There are several other important documents of RAS, like the Regulations for the elections to Academy members; the Regulations for the Departments of RAS; and the Guiding Principles for the organization and the activity of a research Institute of RAS.

5)The Membership of RAS is formed by its Members (Academicians), the Corresponding Members, and Foreign Members. All research institutes, higher educational institutions, state and public organizations have the right to nominate their candidates for the forthcoming elections to academic membership. The names of all candidates for election are published in the press. All categories of members are elected by the General Assembly of RAS out of the candidates elected at the General Meetings of the Departments held prior to the GA of RAS, which convenes every three years. All Academy members are elected for life, and there are no membership dues, on the contrary, both, Members and Corresponding Members of RAS receive a monthly fee out of the funds of the Academy for life. As of June 1, 2008 the total

13

membership of the Russian Academy of Sciences numbers 1600: 522 Members (Academicians); 822 Corresponding Members; and 256 Foreign Members.

6) The Russian Academy of Sciences plays one of the leading roles in Russia in the sphere of integration of academic science within the higher education process. RAS maintains permanent relations with state universities. The Academy has in operation a wide network of Teaching and Scientific Centers (NSC) and Doctoral Studies Departments (DSD) at its Institutes that have been organized jointly with the universities and other higher institutions of Russia, and have become a source of recruitment of talented students and young people to science. The Academy participates practically in all Federal Programs for the integration of science and higher education and for the support of young scientists. Besides, in 2002 the Presidium of RAS launched its own purpose-oriented "Program for the Support of Young Scientists" with an annual financing of 60 million rubles at the start and reaching about 95 million rubles in 2007 that were allocated to 195 institutes of RAS for the support of young researchers. To promote the creative initiative of young scientists and students of higher education establishments in carrying out scientific research, the Russian Academy of Sciences awards annually 12 medals of RAS with bonus for the best scientific works on the natural and technical sciences and the humanities in the main directions of research. Because of demands imposed to the Russian Academy of Sciences throughout its evolution for the progress of science and the development of Russian society, the structure of the Academy was built on two principles: scientific specialization and territorial factors. Thus, RAS incorporates 9 specialized Scientific Departments, each dealing with research in a particular branch of science, 3 Regional Divisions and 14 Regional Centers, which encompass research institutions on a given territory of Russia. A research Institute is the main structural element within the Academy of Sciences. At present 410 scientific institutions are integrated within the RAS. The academic institutes and other scientific establishments employ about 99 500 scientific workers, including 800 Academicians, more than 10 000 Doctors of Science, about 24 400 Candidates of Sciences and about 14 500 scientific workers without a scientific degree. All branches and disciplines of modern science are represented in the Russian Academy of Sciences, like physical and mathematical sciences (mathematics, physics, including nuclear physics, astronomy); engineering sciences (informatics, computer engineering, automation, physical and technical problems of power engineering, mechanical engineering, mechanics and control processes); chemical sciences, life sciences (biology, physiology), earth sciences (geology, geophysics, geochemistry, mining sciences, oceanology, physics of

14

the atmosphere, geography), social sciences and humanities (history, philosophy, psychology, law, economics, international relations, literature and linguistics), etc.

7)The Russian Academy of Sciences is one of the largest publishers of scientific literature in the Russian Federation. Under the Statutes of RAS, the Presidium of RAS guides the publishing activity of the Academy through a Scientific Publishing Council. In the period of 2001-2007 the total publishing output of RAS amounted to 60.000 book and journal titles. "NAUKA" Publishing House is the most important publishing organization of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

8)The Federal budget of the Russian Federation is the main source of funds for RAS that provides for about 60% of total funding. Besides, the Academy has other sources of financial support, like grants from foundations for the support of national science, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, and other sources, mainly related to contracts with industry for the conduct of purpose-oriented research.

9)The Academy of Sciences rewards scientists for outstanding works, discoveries and inventions of major scientific and practical value with medals and prizes named after prominent scientists. The highest award of the Academy is the Large Gold Medal of RAS named after Michael Lomonosov, annually awarded to a Russian and a foreign scientist since 1959.

10)Scientists and researchers of the Academy participate in international scientific cooperation and take part in various international fora around the world, some being organized by the United Nations, UNESCO, UNEP, IAEA, WHO, WMO. Academy members and researchers from its Institutes are in demand as top scientific experts by the industry and the business community. At present the Russian Academy of Sciences enjoys full membership relations with about 50 international non-governmental organizations: well-known science Unions, Associations and Programs (including ICSU family, IIASA, IAP, ALLEA, IGBP, etc.), which embrace practically the whole spectrum of modern basic and applied science, natural sciences, social sciences and humanities, as well as the branches of science dealing with the environment.

1.Find in paragraph 1 the sentences with that and those. Translate the sentences. (Refer to the Grammar revision section).

2.Find in paragraph 3 the phrases with nouns as modifiers. Analyze them and translate. (Refer to the Grammar revision section).

3.Find in paragraph 4 infinitives. Identify their functions and translate the sentences where they are used. (Refer to the Grammar revision section).

15

4.Read the text again and write the questions: general, special, alternative and disjunctive. (Refer to the Grammar revision section).

5.Search for the information about research work organization in other countries. Discuss the similarities and differences.

Science in the New Russia

Loren Graham

Read the text.

In the former Soviet Union, science and technology served as major forces moderating national policies. The advent of nuclear weapons forced the country to give up its earlier Leninist thesis that wars were inevitable events that produce socialist regimes. The development of personal computers and information technology made the tasks of Stalinist-style censors unachievable. Environmental protests over industrial pollution served as models for independent political action on other issues. New biomedical developments forced scientists and philosophers to pay more attention to ethics, a grossly neglected field in Soviet thought. And the damage caused by technocratic planning of industrial expansion led government leaders to pay more attention to social, economic, and cost-benefit modes of analysis. In all of these ways, the advancement of knowledge, particularly in science and technology, helped to mellow the nation's behavior.

Now that the Soviet Union is gone, what roles do science and technology play in the relationship between the United States and the new Russia? An examination of the events of the past dozen years shows that science and technology are still important in Russia, although they now play more subtle roles than earlier. If during the Soviet period science helped change the nation's political system, then models of Western scientific organization are now changing the ways Russian science itself is managed and financed.

Collapse of science

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, science almost collapsed as well. The main source of research funds disappeared. Science was heavily concentrated in one republic--Russia--and its government thought that changing the political, social, and economic systems was more important than helping science, which was regarded as a luxury. Russia's budget for science dropped roughly 10-fold between 1991 and 1999, and thousands of the best scientists emigrated abroad. The crisis was so deep that some people spoke of the "death of Russian science."

16

Western governments, private foundations, and professional scientific organizations came to the aid of Russian science in what the board chairman of a U.S. foundation called "one of the largest programs, if not the largest, of international scientific assistance the world has ever seen." Government donors have included the United States, the European Union, and Japan. In the United States alone, at least 40 government agencies are now involved in science and technology activities in Russia. Private foundations that have provided support include the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Welcome Trust, the Carnegie Corporation, and the U.S. Civilian Research and Development Foundation. One man alone, U.S. financier and philanthropist George Soros, donated more than $130 million through his International Science Foundation between 1993 and 1996. Professional organizations offering aid have included the American Physical Society and the American Mathematical Society, aided by the Sloan Foundation, as well as similar European and Japanese organizations.

Surveys show that the most successful Russian research institutions now derive 25 percent or more of their budgets from foreign sources. In 1999, almost 17 percent of Russia's total gross expenditures on R&D development came from foreign sources--a greater share of outside support for science than that of any other country in the world.

Today, it is clear that Russian science is not dead. And although the scientific enterprise is now less than half the size it was in Soviet times, it will continue to be a vital part of the Russian economy and of Russian culture. The country's economy has begun to recover in the past few years, and starting in 1999 the Russian government has stabilized and even slightly increased its science budget. Although it is impossible to predict the future, the worst period for Russian science is probably over. However, the country's science is emerging from its crisis under heavy pressure, much of it from abroad, to change the way it is managed and financed. In order to understand this new Western influence, it is necessary to review briefly the organizational characteristics of Soviet science, many of which are now under question.

Soviet science and technology were highly centralized and ruled from above. In fundamental science, the Academy of Sciences, a network of several hundred institutes, acted as the major organizational force. The academy's budget came from the central government and was distributed from the top down, in block grants. There were no fellowships and grants for which individual researchers could apply, and there was no system of peer review.

This mode of managing and financing research gave institute directors enormous power, for they controlled the budget. Senior researchers with influence were much more successful in garnering research funds than were junior scientists. Furthermore,

17

research and teaching were largely separated, with the academy responsible for research and the universities assigned a primarily pedagogical role. The result was an exceptionally elitist organization of science, a system in which less prestigious researchers, such as the young or university teachers, had great difficulty in fulfilling their potential. Nonetheless, this system worked fairly well in cases where the elite scientists in charge were talented and productive, as was often the case in such fields as theoretical physics and mathematics. But it worked poorly when second-rate scientists ruled, as was the case in many other fields, such as biology during much of the Soviet period and the social sciences and humanities during all of that period.

Changes raise When the Soviet Union collapsed and foreign foundations entered, a primary question was how does one choose who should receive both the dwindling old money from the Russian government and the growing new money from foreign sources? The old system was clearly authoritarian and inadequate. The Russian government and many scientists looked abroad to democratic countries for models, especially the United States.

Changes raise questions

Within a few years, the Russian government created an analog to the National Science Foundation (the Russian Foundation for Basic Research), as well as an analog to the National Endowment for the Humanities (the Russian Foundation for the Humanities). Rules involving principal investigators, peer review, and accountability-- all new ideas--were introduced, although they remain only partially developed. The foreign foundations also emphasized the development of young scientists, university research, and geographical distribution of grants, also novel ideas. The Russian government sometimes followed suit, especially in a new emphasis on the young.

These changes have resulted in a period of great controversy in Russian science. What is the most effective balance between the old system of block grants and the new system of peer-reviewed individual grants? Under the reformed system of financing research, who should own intellectual property rights? (Everything belonged to the government in Soviet times.) Should universities become major research centers, as in the United States, or should the Academy of Sciences remain as the center of fundamental research? Given that the Soviet Union was rather strong in science, is there a danger that too dramatic a shift to a new system will damage a traditional strength? How can the government prevent Russian researchers from emigrating abroad, while maintaining the freedom of movement that is essential to a democracy?

18

At the moment, it appears unlikely that Russia will completely discard the old system. There almost certainly will be changes, but just how much the country should accept from Western methods of managing and financing scientific research remains a hot topic of internal debate.

Loren R. Graham (lrg@mit.edu) is professor of the history of science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Discussion

1.Make a list of the most important points in the text.

2.Agree or disagree with the author’s statements.

3.What are your views on the past and the future of science in Russia?

Unit 3. MY RESEARCH

3.1. My research work

Read the text

I am an economist in one of the auditing firms. My special subject is accounting. I combine practical work with scientific research, so I am a doctoral candidate (соискатель).

I am doing research in auditing which is now widely used in all fields of economy. This branch of knowledge has been rapidly developing in the last two decades. The obtained results have already found wide application in various spheres of national economy.

I am interested in that part of auditing which includes its internal quality control. I have been working at the problem for two years. I got interested in it when a student.

The theme of the dissertation is “Internal quality control of audit services”. The subject of my thesis is the development of an effective internal quality control system for audit firm services.

I think this problem is very important nowadays as a major part of public accounting practice is involved with auditing. In making decisions it is necessary for the investors, creditors and other interested parties to know whether the financial statements may be relied on. Hence there should be an internal control of auditing operations for insuring the fairness of presentation.

My work is both of theoretical and practical importance. It is based on the theory developed by my research advisor, Professor S. Petrov. He is the head of the department at the University of Economics. I always consult him when I encounter

19

difficulties in my research. We often discuss the collected data. These data enable me to define more precisely the theoretical model of the audit internal quality system.

I have not completed the experimental part of my thesis yet, but I am through with the theoretical part. For the moment I have 4 scientific papers published. One of them was published in the US journal.

I take part in various scientific conferences where I make reports on my subject and participate in scientific discussions and debates.

I am planning to finish writing the dissertation by the end of the next year and prove it in the Scientific Council of the University of Economics. I hope to get a Ph. D. in Economics.

1.Answer the following questions:

1.What are you?

2.What is your special subject?

3.When did you get interested in the problem?

4.Who encouraged your interest in the problem?

5.What field of knowledge are you doing research in?

6.Have you been working at the problem long?

7.Is your work of practical or theoretical importance?

8.Who do you collaborate with?

9.When do you consult your scientific adviser?

10.Have you completed the experimental part of your dissertation?

11.How many scientific papers have you published?

12.Do you take part in the work of scientific conferences?

13.Where and when are you going to get Ph.D. degree?

2.Speak on your research work.

3.2. Taking a Post-Graduate Course

Read the text.

Last year by the decision of the Scientific Council I was admitted to post-graduate studies to get deeper knowledge of economics. I passed entrance examinations and now I am a first year post-graduate student of the University of Economics. I am attached to the Statistics Department. In the course of my post-graduate studies I am to pass candidate examinations in Philosophy, English and the special subject. So I attend courses of English and Philosophy. I am sure the knowledge of English will help me in my research.

20

My research deals with economics. The theme of the dissertation (thesis) is "Computer-Aided Tools for…” I was interested in the problem when a student and now I want to move to deeper understanding of this area.

I work in close contact with my research advisor (supervisor). He graduated from the Moscow State University 15 years ago and got his doctoral degree at the age of 40. He is the youngest Doctor of Sciences at our University. He has published a great number of research papers in journals not only in this country but also abroad. He often takes part in the work of scientific conferences and symposia. When I have difficulties in my work I always consult my research adviser.

At present I am engaged in collecting the necessary data. I hope it will be a success and I will be through with my work on time.

1. Ask your colleague (you may ask any other questions dealing with the topic of discussion):

a)what candidate examinations he/she has already passed;

b)what the theme of his/her dissertation is;

c)who advised him/her to take up this problem;

d) how many scientific papers he/she has published;

e)if he/she is busy with making an experiment;

f)what his/her special subject is;

g)if he/she often takes part in scientific conferences;

h)who his/her advisor is;

i) what he/she is engaged in at present;

2.Share with the class the information you got from your partner.

3.Speak about your taking post-graduate course.

3.3.Choosing a Research Topic

By RICHARD M. RE1S

Read the article.

"It is really important to do the right research as well as to do the research right. You need to do 'wow' research, research that is compelling, not just interesting. (George Springer, chairman of the aeronautics and astronaut department at Stanford

University).

21

Of all the decisions you'll make as an emerging scientist, none is more important than identifying the right research area, and in particular, the right research topic. Your career success will be determined by those two choices.

The research you do as a graduate student will set the stage for your research as a postdoc and as a professor. While it is unlikely that your later research will be a straightforward extension of your dissertation, it is also unlikely that it will be completely outside your Held. Stories to the contrary are the exception, not the rule. The knowledge, expertise, and skills that you gain early on will form the foundation for your later investigations. Choosing the right topic as a graduate student will help you insure that your research will be viable in the future. The right topic will be interesting to you, complex, and compelling.

According to Cliff Davidson and Susan Ambrose of Carnegie Mellon University, "The most successful research topics are narrowly focused and carefully defined, but are important parts of a broad-ranging, complex problem."

Finding the ideal research problem does not mean simply selecting a topic from possibilities presented by your adviser or having such a topic assigned to you, attractive as this may first appear. It means going through the process of discovering and then developing a topic with all the initial anxiety and uncertainty such a choice entails. This is how you develop your capacity for independent thought.

There are a number of factors to consider when selecting a research area. Some of them have to do with your particular interests, capabilities, and motivations. Others center on areas that will be of greatest interest to both the academic and private sectors.

The chemistry professor and author, Robert Smith, in his book Graduate Research: A Guide for Students in the Sciences (ISI Press, 1984), lists 11 points to consider in finding and developing a research topic:

1.Can it be enthusiastically pursued?

2.Can interest be sustained by it?

3.Is the problem solvable?

4.Is it worth doing?

5.Will it lead to other research problems?

6.Is it manageable in size?

7.What is the potential for making an original contribution to the literature in the field?

8.If the problem is solved, will the results be reviewed well by scholars in your field?

22

9.Are you, or will you become, competent to solve it?

10.By solving it, will you have demonstrated independent skills in your discipline?

11.Will the necessary research prepare you in an area of demand or promise for the future?

Let's take a closer look at Mr. Smith's list. Clearly it is important to pick a problem you are enthusiastic about (1), and one that will interest you over the long haul (2). Much research is just that, re-search. At times it will be mundane, and it will surely be frustrating. Experiments won't go right; equipment will fail; data from other sources won't arrive on time (or at all); researchers who pledged their assistance won't come through as expected, while others will do work that competes with your research. During these times you'll need courage and fortitude.

Picking a problem that you can solve in a reasonable period of time (3), that will lead to further research (5), and that is manageable in size (6) is a particular challenge for most graduate students and postdocs. Doctoral students tend to take on more than is necessary to achieve what ought to be their goal: completing a dissertation or obtaining another publication or two. That's why it is essential to have the right supervisor. It's his or her job to help you determine how to make your dissertation original and publishable, yet also manageable. There will be plenty of time for further work after you complete the Ph.D.

Whether or not a problem is worth solving (4), will make an original contribution to the literature in your field (7), and if solved, will have results that will garner the attention of scholars in your discipline (8), is at the heart of what is meant by choosing compelling topics leading to a meaningful "stream of ideas."

One way to tell if a subject is compelling is to note how many people attend seminars or symposia on different research topics. In some cases, attendance may be up for big-name speakers, but often it is because the work presented is of broad interest. These seminars can give you clues to possible research directions and topics. Of course, going into an area where there are too many other researchers has its drawbacks, but beware of going to the opposite extreme. You don't want to be the only researcher in an area that has little chance of drawing interest or support.

Your capacity to tackle the problem (9) will depend somewhat on your innate abilities. However, to solve the problem you'll also need to develop basic knowledge and technical understanding, computer skills, and experimental expertise. To acquire such skills you'll need direct access or Web access to courses and seminars, library

23

materials, independent-study opportunities, and most importantly, other students, postdocs, faculty members, and even industrial scientists and engineers.

To develop independent skills in your discipline (10), start by defining and developing a problem that is sufficiently robust. You'll then need to acquire a fundamental understanding of certain phenomena or behaviors and experimental techniques in order to solve the problem. However, as Peter Feibelnmn, author of the popular book A Ph.D. is Not Enough (Addison-Wesley, 1993), says: "It is important that your focus be on problems and not on techniques or specialized tools. The latter come and go and as a researcher you want to be able to shift your approaches as needed to solve the more fundamental problems."

Choosing a research area that will be in future demand (11) can be tricky. Some fields, such as semiconductor physics and fiber optics, may have been compelling for some time, but are now approaching maturity and shifting focus and are likely to be less promising in the future.

Other areas, such as telecommunications and biotechnology, are quite popular. However, their very popularity may have oversaturated the fields. In such cases, large numbers of investigators often compete for limited financial and experimental resources.

Some fields drive the technology for other fields, and therefore may be in a better position to thrive as specific applications shift. You need to look at emerging fields and see if your work can affect these areas in some specific way. For example, work on amorphous silicon may apply to the emerging field of flat-panel displays, which, in turn, is part of an even broader field of low-power portable communications systems.

Finally, you need to pay attention to the broader implications of your work and to the possible appeal such work has to both academia and industry. As Smith notes:

«Interdisciplinary research is no substitute for good disciplinary training during the greater part of a graduate career. It is advisable, however, to seek exposure to interdisciplinary activities in graduate as well as postdoctoral training since most researchers engage in interdisciplinary research during their professional careers."

Once you've found the ideal research topic, your next challenge will be choosing the right research adviser. I will discuss a strategy for doing just that in my next column.

1. Find in the text the sentences where –ing forms of the verbs are used. Identify their functions and translate the sentences. (Refer to the Grammar revision section).

24

2.Find in the text adjectives and adverbs. Analyze their forms. (Refer to the

Grammar revision section).

3.Answer the questions.

1.Why is it important to choose the right research topic?

2.What are the factors that must be considered when selecting a research area?

3.What is a research?

4.What is the topic of your research?

5.Why have you chosen this topic?

6.Is it important to have a good advisor? Why?

4.Find Russian equivalents of the underlined words and phrases. Translate the text.

5.Render the text. (Refer to the “Recommendations for making rendering” in the

Supplementary Material section).

Unit 4. COMMUNICATION FOR SCIENTISTS

Communication is an integral part of the research you perform as a scientist. Your written papers serve as a gauge of your scientific productivity and provide a longlasting body of knowledge from which other scientists can build their research. The oral presentations you deliver make your latest research known to the community, helping your peers stay up to date. Discussions enable you to exchange ideas and points of view. Letters, email, and memos help you build and maintain relationships with colleagues.

So, the main activities you are involved in as a scientist are writing scientific papers, writing correspondence, giving oral presentations and interacting during conferences sessions.

For Writing Scientific Papers you should know how to select and organize a paper's content, draft it more effectively, and revise it efficiently. You must know general rules for text mechanics and how to use appropriate specific language.

Writing Correspondence skills will help you communicate effectively with your colleagues. Here you must know how to select an appropriate tone for corresponding in English.

For Giving Oral Presentations you should develop skills to select and organize the content of an oral presentation, create effective slides to support it, deliver the presentation effectively, and answer questions usefully.

25

Skills at Interacting during Conference Sessions will help you create, promote, and present scientific posters effectively, chair a conference session or moderate a panel, and finally take part in a panel discussion.

4.1. Scientific writing

As a scientist, you are expected to share your research work with others in various forms. Probably the most demanding of these forms is the paper published in a scientific journal. Such papers have high standards of quality, and they are formally disseminated and archived. Therefore, they constitute valuable, lasting references for other scientists — and for you, too. In fact, the number of papers you publish and their importance (as suggested by their impact factor) are often viewed as a reflection of your scientific achievements. Writing high-quality scientific papers takes time, but it is time well invested.

WRITING SCIENTIFIC PAPER

Scientific papers typically have two audiences: first, the referees, who help the journal editor, decide whether a paper is suitable for publication; and second, the journal readers themselves, who may be more or less knowledgeable about the topic addressed in the paper. To be accepted by referees and cited by readers, papers must do more than simply present a chronological account of the research work. Rather, they must convince their audience that the research presented is important, valid, and relevant to other scientists in the same field. To this end, they must emphasize both the motivation for the work and the outcome of it, and they must include just enough evidence to establish the validity of this outcome.

Papers that report experimental work are often structured chronologically in five sections: first, Introduction; then Materials and Methods, Results, and Discussion

(together, these three sections make up the paper's body); and finally, Conclusion.

The Introduction section clarifies the motivation for the work presented and prepares readers for the structure of the paper.

The Materials and Methods section provides sufficient detail for other scientists to reproduce the experiments presented in the paper. In some journals, this information is placed in an appendix, because it is not what most readers want to know first.

The Results and Discussion sections present and discuss the research results, respectively. They are often usefully combined into one section, however,

26

because readers can seldom make sense of results alone without accompanying interpretation — they need to be told what the results mean.

The Conclusion section presents the outcome of the work by interpreting the findings at a higher level of abstraction than the Discussion and by relating these findings to the motivation stated in the Introduction.

Papers reporting something other than experiments, such as a new method or technology, or other, typically have different supporting sections in their body, but they include the same Introduction and Conclusion sections as described above.

Although the above structure reflects the progression of most research projects, effective papers typically break the chronology in at least three ways to present their content in the order in which the audience will most likely want to read it. First and foremost, they summarize the motivation for, and the outcome of, the work in an abstract, located before the Introduction. In a sense, they reveal the beginning and end of the story — briefly — before providing the full story. Second, they move the more detailed, less important parts of the body to the end of the paper in one or more appendices so that these parts do not stand in the readers' way. Finally, they structure the content in the body in theorem-proof fashion, stating first what readers must remember (for example, as the first sentence of a paragraph) and then presenting evidence to support this statement.

Summing up, you should consider the following sections of a research paper:

Title

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

In order to produce a fluent and cohesive piece of writing the compositional parts should be linked accurately. Signposting and transition words will help convey your message through the appropriate structure at all levels.

27

Here are some signposting words used in the different parts on the paper

Introducing theory |

linking |

Concluding |

|

|

|

State |

Because |

Summing up |

Argue |

However |

In summary |

Propose |

But |

To summarize |

Suggest |

Since |

In sum |

Point out |

Also |

To conclude |

Believe |

As a result |

This demonstrates |

Observe |

So |

This indicates |

Assert |

Controversially |

In conclusion |

contend |

As well as |

Briefly |

|

|

|

(For more signposting and transition words refer to”Recommendations for making rendering» in the Supplementary Material section).

Read the article.

The Journal of Applied Business Research Volume 17, Number 4

The Potential of the APEC Grouping to Promote Intra-Regional Trade in the Asia-

Pacific Region

Donny Tang, (Email: dtang@fastmail.ca). University of Toronto

Abstract

This study examines whether the proposed APEC free trade area would promote a high level of intra-APEC trade after its completion. To achieve this goal, a modified gravity model is estimated for the thirteen APEC countries based on annual trade data from 1989 to 1998. The results indicate that a high level of trade interdependence already exists to help promote the intra-APEC trade flows after its FTA completion. The results also suggest that the APEC countries are more likely to trade with other member countries than with non-member countries

Introduction

Exactly eleven years ago, the Asia-Pacific countries created what was to become the most influential regional trading arrangement in the world. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) grouping encompasses three major regional trading

28

arrangements in the world - North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations (ANZCER) (Frankel et al., 1996). These three trading arrangements comprise the world's leading trading partners. By rough measure, the total share of APEC exports in 1995 already exceeded half of the world trade (Langhammer, 1999), According to estimation, the prospective APEC Free Trade Area will account for more than 60% of the world's Gross National Product. With the inclusion of leading trading nations and the significant share of world trade, the APEC has the full potential to become a major trading bloc second only to the European Union (EU). A central issue arises whether the APEC trading arrangement has promoted the intra-APEC trade flows since its formation in 1989.

Compared to other trading arrangements, the APEC has progressed very rapidly from a trade discussion forum group to a formalized trade liberalization organization (Cheong, 1997). Within five years of its formation, a free trade area (FTA) was proposed at the 1994 summit meeting. The full-scale FTA would include the United States, Canada, Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Chile, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Brunei, and New Guinea. Adhered to the open regionalism principle, the APEC would utilize the FTA to foster free trade through extending the tariff reduction measures to both member and non-member countries (Frankel et al, 1998).

The road map to form the FTA was clearly drawn out during the three summit meetings from 1994 to 1996, In the 1994 summit meeting, the Bogor Declaration established the objective of forming the FTA for developed countries by 2010 and for developing countries by 2020 (Krueger, 1999). At the subsequent summit meeting in 1995, the Osaka Action Agenda (OAA) was agreed on by all member countries to implement the objectives of the Bogor Declaration.

The OAA consists of two major components: (1) trade liberalization and (2) economic and technical со-operation. The trade liberalization includes policy measures on tariff and non-tariff reductions such as customs procedures, rules of origin, standards and conformance, and competition policy. The economic and technical co-operation includes key programs on industrial science and technology, economic infrastructures, and telecommunications and information (Yamazawa, 1997). In the 1996 summit meeting, each member country submitted the so-called Individual Action Plans (IAP) to show how to implement all those OAAs. The trade liberalization efforts achieved by the АРБС during the mid-1990s mark the first major step to progress toward deeper integration.

29

The majority of literature on the APEC integration focuses on the prospects for the APEC РТА. A recent study by Sharma (2000) revealed that the intra-APEC trade increased substantially after its formation in 1989. A noticeable increase was found between the ASEAN countries and the rest of the APEC countries. This high degree of intra-APEC trade flows provides the ideal condition to form a full-scale FTA similar to the NAFTA.

Other studies went a step further to examine the potential benefits of shaping the FTA based on open regionalism approach. The main conclusion is that such approach should lead to higher economic growth for integrating countries. According to Vamvakidis (1999), closed economies should choose open regionalism rather than preferential (discriminatory) free trade approach. Vamvakidis results confirm the expectation that the economies experience higher economic growth by using open regionalism. Cheong (1998) study reached similar conclusion. In a competitive global economy, the APEC would benefit higher welfare gains under open regionalism approach. This happens because there is no trade diversion under unilateral extension of trade liberalization. The majority of these studies seem to support the use of open regionalism approach in the APEC FTA.

The purpose of this study is to examine the level of trade interdependence among the APEC countries between 1989 and 1998. Specifically, this study will utilize the gravity model to test whether a high level of trade interdependence already exists to help promote the intra-APEC trade flows after the FTA completion. The prospect for a higher level of the APEC integration is important for two reasons. First, the high economic growth among the APEC countries (ASEAN, NAFTA, and ANZCER) helped accelerate the intra-regional trade across these groupings. The increased intraAPEC trade among these groupings in three continents provides the ideal condition for the APEC to progress from regional to global trade liberalization in the next decade. Second, the trend of a regional grouping integrating with another regional grouping will continue as we enter the next century. Almost all major trading nations belong to at least one regional trading grouping (Frankel and Wei, 1998). There are clear indications that the major APEC members (i.e., NAFTA and ASEAN) are developing closer economic ties with the EU (Hajidimitriou and Mourdoukoutas, 1999). If the APEC and EU integrate with each other in some way, it would certainly emerge as the most dominant trading bloc in the world.

The paper is divided into three sections. The first section describes the methodology used in this study. It is followed by a discussion of the empirical results.