Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

Eye Disorders

Children maypresenttopediatricians withvariousprimary eye problems. Several systemic diseases have ocular manifestations, someofwhichare very usefulin making the correct diagnosis and instituting appropriate management. Finally, therapies for some diseases are known to have ocular side effects which need to be recognized.

PEDIATRIC EYE SCREENING

The concept of screening children for eye diseases is based on the awareness that infants and young children cannot communicate their symptoms and visual difficulties. In addition, several potentially blinding diseases manifest in this age group; their early detection and treatment can limit ocular morbidity and prevent irreversible blindness.

The goal of pediatric eye screening is to detect eye and visual disorders in children or identify their risk factors so that the child can be referred for detailed ophthalmic evaluation, confirmation of diagnosis and appropriate medical management.

Comprehensive Pediatric Eye Evaluation

Presenceof any of thefollowingriskfactors is an indication for referral for comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation.

I.General health condition, systemic disease or use of medications associated with eye disease

•Extreme prematurity (gestational age .:s;30 weeks); suspected retinopathy of prematurity

•Intrauterine growth retardation

•Perinatal complications

•Neurological disorders

•Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

•Thyroid disease

•Craniofacial abnormalities

•Diabetes mellitus

•Syndromes with known ocular manifestations

•Chronic steroid therapy; use of hydroxychloroquine or other medications known to affect eyes

•Suspected child abuse

Radhika Tandon

II.Family history of any of the following

•Retinoblastoma

•Childhood cataract

•Childhood glaucoma

•Refractive errors in early childhood

•Retinal dystrophy or degeneration

•Strabismus and/or amblyopia

•Sickle cell disease

•Syndromes with ocular manifestations

•Nontraumatic childhood blindness

III.Signs or symptoms reported by the family, health care provider or school teacher

•Defective ocular fixation or visual interactions

•Abnormal appearance of the eye(s)

•Squinting or tendency to close one eye in certain situations

•Any obvious ocular alignment, movement abnor- mality, head tilt or nystagmus

•Large and/or cloudy eye(s)

•Drooping of the eyelid(s)

•Lumps or swelling around the eye(s)

•Persistent or recurrent tearing, sticky discharge, redness, itching or photophobia

•Learning disabilities or dyslexia

Guidelines for Examination

Children are best examined in a comfortable and friendly environment. Very young children can remain in the lap of their mother while olderchildrencan be distracted with toys and colorful objects. When the child first enters the room, simple observation ofbehavior,fixation,movement and general awareness of the surroundings are good indicators of the child's visual status, and gross abnor malities can be detected.

Steadyfixationanduniformsteadyalignmentoftheeyes develop in the first 4-6 weeks. Visual acuity assessment in children less than 6 months of age is limited to seeingif the child attempts to fix and follow light. A child 6-12 months

665

-L...E_s_s_e_ n_t_ia_l_P_e_d_ i_a _tr_ic_s_________________________________

of age can follow and even reach out towards colorful objects, andthis permits a very crude assessment of gross visual ability. A more objective assessment can be made with electrophysiological tests using a pattern-induced visual evoked response (pattern VER) using chequered patterns of varying degrees of resolution or by observing the optokinetic response or nystagmus induced by the child'sattempttoviewastripedpatternonamovingdrum (OKN).Both these testsare an assessment of the resolution acuityorpoweroftheeyetodistinguishpatternsofvarying degrees of separation or width. These tests are expensive and not readily available in routine clinics. For most preverbal children up to the age of 3 yr, a simple obser vationoffixationpatternandbehavior,abilitytosee,follow orpick-upsmallobjectsliketoysorcandybeads, preferen tial looking tests using Teller acuity cards or preferential looking cards are used to estimate the visual status. Unilateral loss is also tested for by observing if the child resists closure or occlusion of one eye over the other.

Vision of children 3-5 yr of age can be assessed using picture tests and symbols withmatching cards such as the Kays symbols, tumbling E or HOTV card tests where one relieson thechild'sabilitytorecognizetheshapeandmatch theshapewithasimilaroneonacard.Children5yrorolder can be tested with more conventional vision testing methods using a Snellen visual acuity chart with either alphabets or tumbling E or Landoldts C symbols.

Ocular movements and external examination of the eye can be performed by using adequate illumination with a torch and aided by toys or colorful pictures to capture the child's attention and interest to cooperate with the exa miner. Pupillary reactions must be tested and fundus examination should be attempted with a direct ophthal moscope through theundilatedpupil to view thedisc and macula. Incaserequired, more detailedexaminationofthe fundus and retinal periphery can be carried out after dila ting the pupils with mydriatic eye drops such as 2.5% phenylephrineorshort-actingcyloplegic-mydriaticdrops such as 0.5% tropicamide or 1% cyclopentolate eye drops. The retinaisbest viewedwith anindirectophthalmoscope as this gives the maximum field of view and the exami nation can be completed efficiently. In general, as far as possible, most of the examination should be completed without touching orgoingtooclosetothechildso thatthe childis comfortable anddoes not feel intimidated. Digital assessmentof the intraocular pressure, eversion ofthe lids and slit lamp examination are occasionally required. In certain situations, an examination under anesthesia is required and should be done only after obtaining the parents' informed consent.

CONGENITAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL ABNORMALITIES

This group of diseases may or may not manifest at birth. If the disease is detected at birth, it is 'congenital' such as lid coloboma, severe corneal opacity or total cataract with a white opaque lens. Sometimes the disease is present at

birth, but isdetectedlateron, forexample, apartialcataract or mild congenital glaucoma. Sometimes the disease is a defect of development but manifests later, such as deve lopmental cataract or juvenile glaucoma.

Disorders in Development of the Whole Eyeball (Globe Abnormalities)

A child may be born with a small eye (microphthalmos or nanophthalmos), absent eyeball (anophthalmos) with or without an orbital cyst, or more complex abnormalities associated with craniofacial dysgenesis.

Abnormalities of Development of the Orbit, Eyelids and Adnexa (Lacrimal Drainage System and Glands)

Children are sometimes born with the eyes completely covered by the eyelids so that the globe is not apparent or visible (cryptophthalmos). A blocked nasolacrimal duct may manifest at birth as a dacryocystocele, or later as dacryocystitis. Lacrimal diverticulae or fistula are other abnormalities which may or may not be apparent at birth. Telangiectasias and vascular abnormalities such as capillary or cavernous hemangioma,lymphhemangioma, arteriovenous malformations and orbital varices may be present as isolated abnormalities or as part of syndromes such as the phakomatoses.

Other abnormalities of the lids include abnormal shape and position such as blepharophimosis, ptosis, prominent epicanthic folds, lid coloboma, congenital ichthyosis, entropionandectropion.Earlyoculoplasticreconstruction needs to be undertaken if the visual axis is covered or the cornea is at risk of exposure keratopathy due to lago phthalmos or inadequate lid closure.

Diseases Affecting the Conjunctiva and Anterior Segment

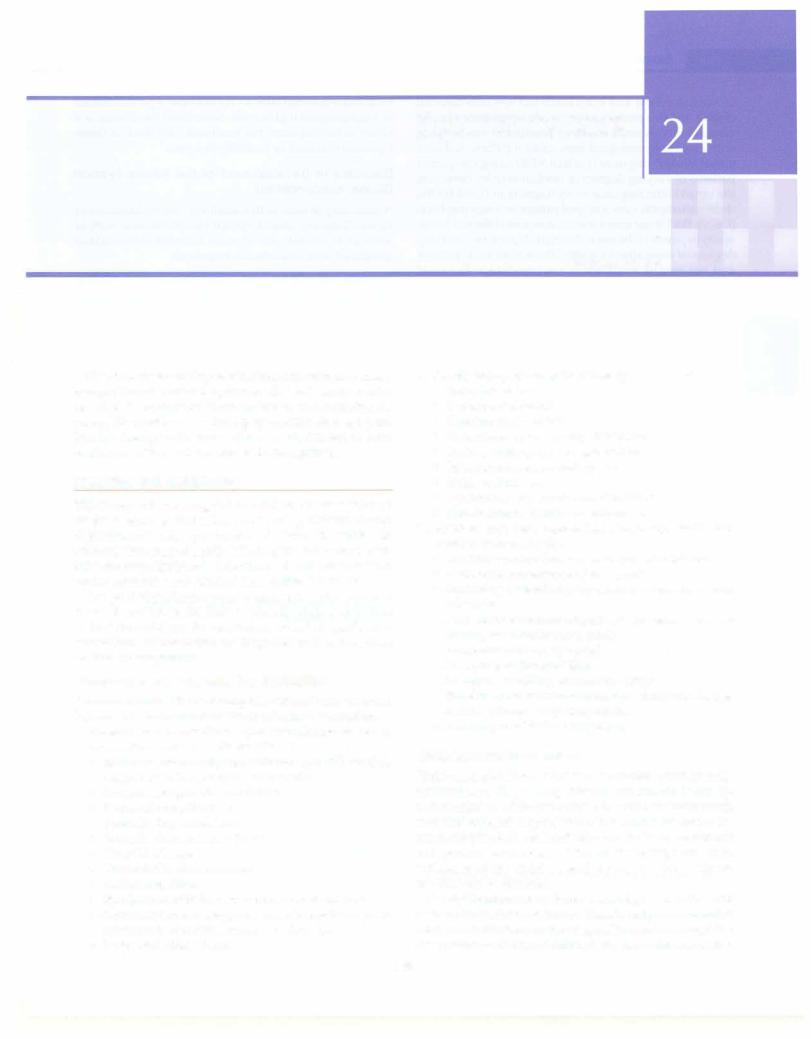

Some of theimportantconditionsthat may be seen include conjunctiva} telangiectasia, hazy or opaque cornea (causes of which can be memorized using the mnemonic STUMPED, i.e. sclerocornea, birth trauma, ulcer, muco polysaccharidosis, Peter anomaly, endothelial dystrophy or endothelial dysfunction secondary to congenital glaucoma, and dermoid); flat cornea (cornea plana), anterior segment dysgenesis, aniridia, iris coloboma, primary congenital or juvenile developmental glaucoma, lens opacity or cataract, lens coloboma, displaced or subluxated lens or ectopia lentis, abnormal shape of lens such as microspherophakia, lens coloboma,lenticonusand persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (Fig. 24.1).

Retinopathy of Prematurity

This condition is seen in preterm babies due to early exposure to oxygen and other environmental factors by a premature, underdeveloped retinal vascular system. The chief risk factors are prematurity, especially birth before 32 weeks of gestation, birth weight less than 1500 g and presence of other contributory risk factors such as

------------------------------------E_y_e _D_is_o_rd_ e_ r_s.........

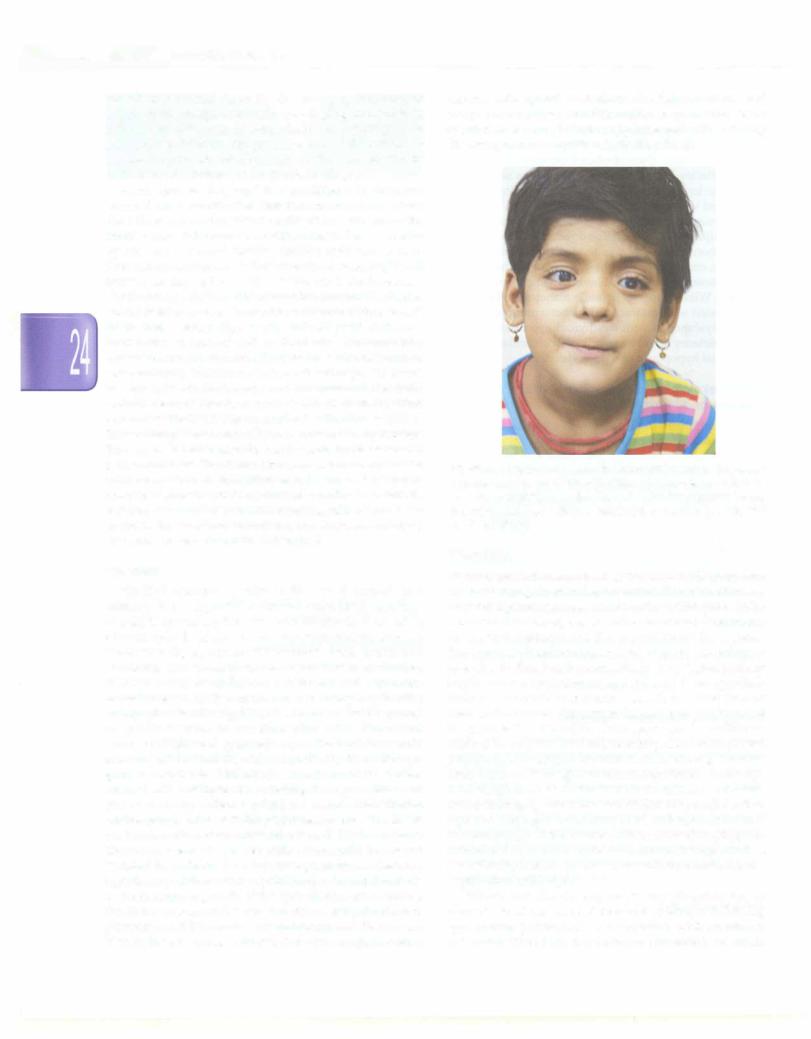

Fig. 24.1: Child with bilateral congenital corneal opacity. Differential diagnoses include all causes of congenital corneal opacity, congenital glaucoma with buphthalmos and corneal edema due to raised intraocular pressure

supplemental oxygen therapy, hypoxemia, hypercarbia and concurrent illnesses like septicemia. The clinical features are graded in stages of severity depending on the retinalsigns andthe zoneof retina involved. Children at risk should be screenedperiodicallyto lookfor evidence of developing what is considered as'threshold' disease, i.e. requiringablative lasertreatment of the avascular zone of the retina to check further progression and prevent blinding stages of the disease which would then require surgical intervention to treat the ensuing retinal detachment and other complications.

ACQUIRED EYE DISEASES

Nutritional Disorders

The most important condition in this category is vitamin A deficiency which can be catastrophic in young children if severe enough to produce keratomalacia. Up to the age of six months, children have adequate hepatic reserves of vitamin A. However, if the mother's nutrition is poor or the infant is not properly fed afterbirth, severe vitamin A deficiency may be precipitated by an attack of acute respiratory infectionsuchas measles, pneumonia or acute gastroenteritis, whichcould lead to bilateral blindness due to severe keratomalacia. Milder forms of vitamin A defi ciency may manifest with xerosis of the conjunctiva, Bitot spot and nyctalopia or night blindness. Adequate nutri tional advice to the pregnant and lactating mother and proper weaning with vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables is advised. Keratomalacia is treated with oral vitamin A 200,000 IU stat followed by a second dose after 24 hr and a third dose after 2 weeks. In case the child is vomiting and cannot retain oral supplement, an intramuscular injection of vitamin A may be given instead. For children less than 1 yr of age and those weighing less than 10 kg, half the dose is given to avoid vitamin A toxicity and vitamin A induced intracranial hypertension.

Infections

Preseptalcellulitisandorbitalcellulitismanifestasswelling and inflammation of the eyelids, are differentiated clini cally, and often occur due to spread of infection from the lids, adnexa or paranasal sinuses or following trauma. These arepotentially dangerousinfections astheyinvolve the anatomical'dangerous area of the face' and if not trea ted promptly and adequately, can spread intracranially, resulting in meningitis or cavernous sinus thrombosis. Ultrasonography is required to detect an orbital abscess, which has to be drained. CT scan or MRI is required if involvement of adjacent paranasal sinuses or intracranial involvement is suspected. Treatment requires systemic antibioticsandanti-inflammatoryagents, supplementation with topical antibiotics, and supportive measures, inclu ding lubricating eyedrops to prevent corneal damage.

Other infections involving the eyelids include blepha ritis, hordeolum externum (stye), hordeolum internum (infectedchalazion),molluscumcontagiosumandphthiri asisoftheeyelashes.Lidhygiene,hotfomentationandlocal antibiotic ointments are useful along with instructions for personal hygiene. Phthiriasis will require mechanical removalofnits adheringtotheeyelashes,localapplication of 20% fluorescein sodium tothe lid margins and systemic ivermectintherapyforrecalcitrantcases, alongwithadvice on hygiene and treatment of other affected family members.

Common infections of the ocular surface include con junctivitis which could be bacterial, viral or chlamydial. Conjunctivitis occurring within the first month after birth is called ophthalmia neonatorwn. Every effort should be made to identify the etiologic agent, especially incases of ophthalmia neonatorum, since gonococcal conjunctivitis can cause loss of vision in the newborn. Conjunctiva! smears and swabs can be sent for microbiological evaluation. Mucopurulent conjunctivitis is treated with topical anti bioticeyedropsandsupportive measuressuchascleansing the eye with clean water, lubricating eyedrops and cold compresses.

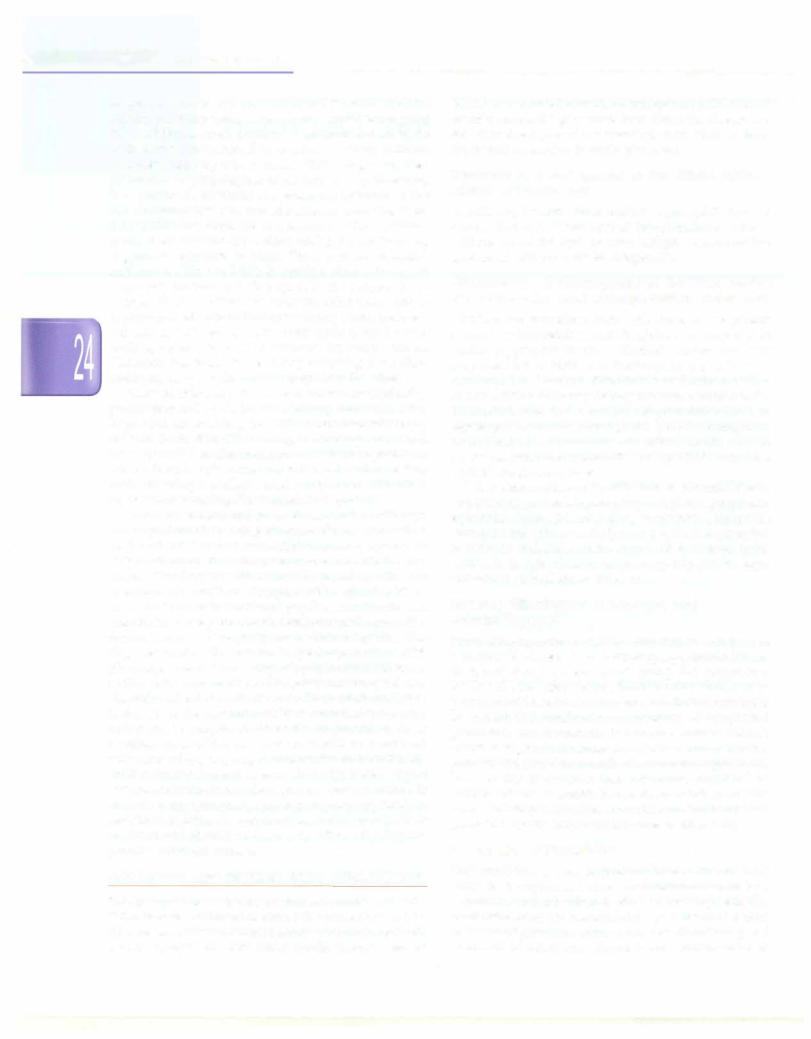

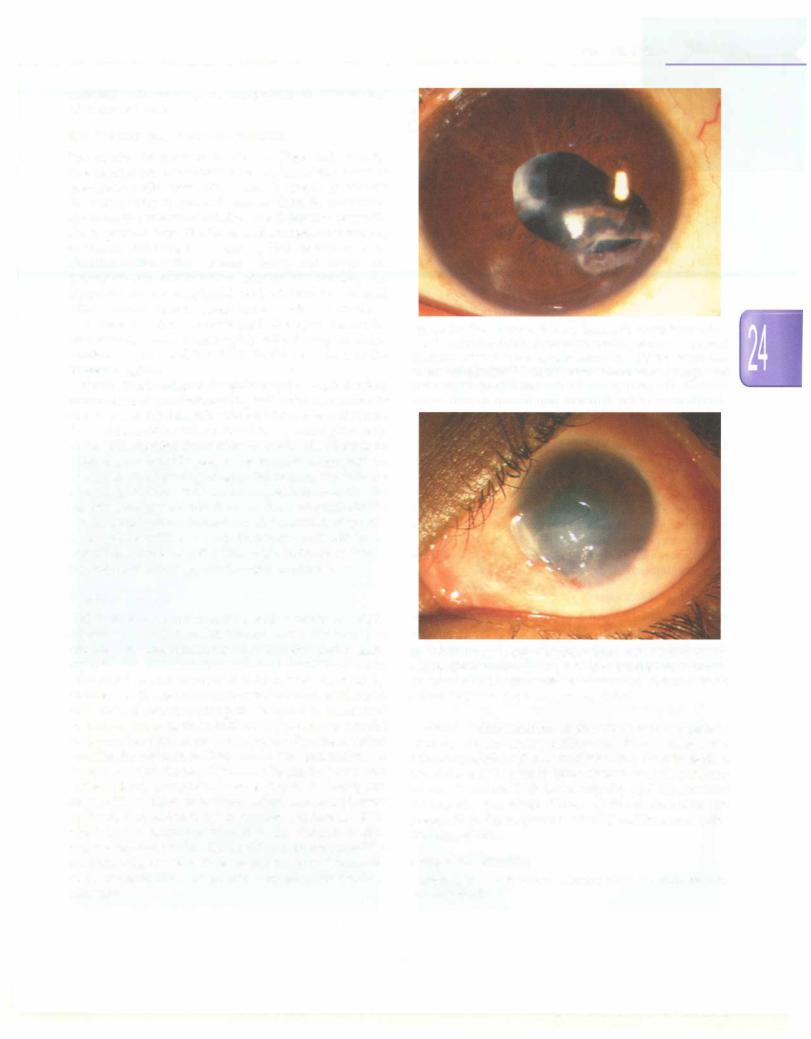

More severe infections include keratitis and corneal ulcers (Fig. 24.2). Traumais the most common underlying predisposing factor, but poor hygiene and lowering of local immunity secondary to chronic inflammation, viral infections or use of topical steroids are other risk factors for bacterial and fungal infections of the cornea. Trauma with vegetative matter, such as a thorn, tree branch or wooden broomstick (often used for making 'bows and arrows' for playing), predisposes to fungal infections. Corneal ulcers require an examination under anesthesia for detailed evaluation and corneal scraping for micro biological analysis. Empiricaltherapy for bacterial corneal ulcers is started with a combination of freshly prepared fortified topicalantibioticssuch as 5% cephazolin and 1.3% tobramycin eye drops hourly and half hourly alternately round the clock for the first 48 hr. After 48 hr, the culture report and clinical response are reviewed. If there is no

__Essen tia1Ped ia trics_________________________________

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Fig. 24.2: A partially treated hypopyon corneal ulcer. The overlying epithelial defect has healed, but there is a deep corneal abscess, corneal edema and purulent fluid, i.e. hypopyon in the anterior chamber

substantialclinical improvement, the antibioticis changed based on microbiology results. If clinically responding to therapy, the frequency of antibiotics can be reduced to use during waking hours only, followed two days later by two hourly application, then reduced to 4 hourly or 6 hourly, and discontinued a week after the ulcer has healed. Supportive measures include topical cycloplegics, hot fomentation, analgesics, antiglaucoma medication if secondary glaucoma is present, and antibiotic ointment at night. Fungal keratitis is treated with topical natamycin (5%) 1 hourly with supportive measures. Herpes simplex viral keratitis is treated with topical acyclovir 3% eye ointmentforepithelialinvolvementandsystemicacyclovir for herpetic keratouveitis or recurrent disease.

Other infections include endophthalmitis (traumatic, metastatic, or iatrogenic following intraocular surgery) and parasitic infestations, such as toxoplasmosis, toxo cariasis, and cysticercosis of the eye, extraocular muscles or orbit.

Allergic and Inflammatory Diseases

Children maydevelop allergic diseases of the skin around the eye and the ocularsurface and conjunctiva. Dermatitis may be an allergic reaction to localophthalmicmedication or sometimes secondary to insect bite, application of traditional eye medicines or herbal remedies and use of local creams or lotions. In addition, a variety of environ mental and hereditary factors may interplay to produce a variety of allergic conjunctival manifestations such as seasonal allergic conjunctivitis, hay fever conjunctivitis, perennial or chronic allergic conjunctivitis, atopic allergic conjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Itching, redness, discomfort, gritty or foreign body sensation, watering, mucoid or thick ropy discharge, photophobia

and blepharospasm are all seen in different combinations and varying degrees of severity. Treatment includes cold compresses,topicalantihistarninic eyedropsfor mildcases and counseling to avoid rubbing the eyes. Topical corticosteroid eyedrops give quick relief but are best avoided in mildcasesbecause of the danger of self-medi cation and unsupervised chronic topical use complicated by steroid induced glaucoma and secondary corneal infection and ulceration. More severe allergies may have secondary consequences in the form of dry eye, kerato pathy and corneal ulceration. These are best referred to ophthalmologists for expert management and careful followup.

Other inflammatory diseases include phlyctenular conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis (believed to be an 'allergic' immunological reaction to tubercular antigen); interstitial keratitis secondary to infections like rubella, syphilis, leprosy and tuberculosis; and uveitis, either idiopathic or associated with juvenile chronic arthritis, psoriasis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and toxoplasmosis. Acute anterior uveitis (iritis, cyclitis and iridocyclitis) usuallypresentswitharedinflamedeyewithphotophobia and diminution of vision. Chronic uveitis may be less symptomatic with decreased vision due to complicated cataract. Intermediate and posterior uveitis (pars planitis, vitritis, retinitis, choroiditis and retinochoroiditis) are usually painless with symptoms of decreased vision (due to hazy media and retinal or optic nerve swelling and inflammation) and floaters (due to inflammatory cells in the vitreous). Treatment is with topicalcycloplegicagents and steroids, supplemented with systemic steroids and specific therapy for any underlying disease, such as tuberculosis. Patients with uveitis need detailed exami nation with a slit lamp biomicroscope to identify the inflammatory response, ophthalmoscopy to view the fundus and specialist ophthalmic care and followup to control the inflammation and minimize the morbidity related to the disease and its treatment.

Intraocular (retinoblastoma or juvenile xanthogranu loma) or systemic malignant disorders may sometimes mimic uveitis syndrome due to malignant cells in the eye and vascular uveal tracts.

Optic neuritis is another important inflammatory disease which couldbeidiopathic, secondaryto infections or associated with demyelinating disorders. Classical features include a rapiddropin vision, usually in one eye, which is accompanied by a relative afferent pupillary defectand normalfundus (retrobulbar neuritis) or inflam matory swelling of the optic disc (papillitis) and retinal edema and/or exudates (neuroretinitis). Patients need to be treated in consultation with a neuroophthalmologist after investigations to identify the cause.

Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders

Homocystinuria isassociatedwithsubluxationof the lens, and secondary glaucoma can be seen as a complication.

-------------------------------------E_y_e_D_is_o_r_d_e_rs__

The lens is usually subluxated downwards which causes poor vision due todisplacementand astigmatism. Surgical lens removal has to be done under general anesthesia taking suitable precautions, as the patients are prone to thromboembolism. Optical rehabilitation is usually done with spectacles or contact lenses, though in some cases intraocular lensescan be fitted using scleral or bag fixation augmented with bag fixation devices.

Various storage disorders such as cerebral storage disease, lipidosis and gangliosidosis may be associated with a 'cherry red spot' due to abnormal deposition in the retina, corneal clouding as in some of the mucopoly saccharidoses, and Kayser-Fleischer ring in peripheral cornea in Wilson disease. Juvenile diabetes mellitus may be associated with cataract and diabetic retinopathy and thyroid dysfunction with dysthyroid eye disease. Tyro sinase deficiency might be associated with ocular albinism with foveal hypoplasia and poor vision.

Musculoskeletal and Neurodegenerative

Diseases and Phakomatoses

Marfan and Ehlers Danlos syndromes may be associated withsubluxatedlensandconsequentsecondaryglaucoma. Marfan syndrome is usually associated with upward and outward displacement of the lenses and myopia with blurred vision. Retinal detachment is not connected also common. Surgical lens removal becomes necessary if the vision is not corrected with spectacles or contact lenses. Leukodystrophies and demyelinating diseases may be associated with extraocular muscle weakness, ptosis and optic neuropathy. Phakomatoses like neurofibromatosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome and nevus of Ota may be associatedwithcafeau laitspots, plexiformneurofibromas of the lids and orbit and Lisch nodules on the iris and glaucoma.

Muscular dystrophies or degenerations such as chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia result in ptosis and restriction of eye movements. Duchenne muscular dystrophy may be associated with cataracts.

Tumors and Neoplastic Diseases

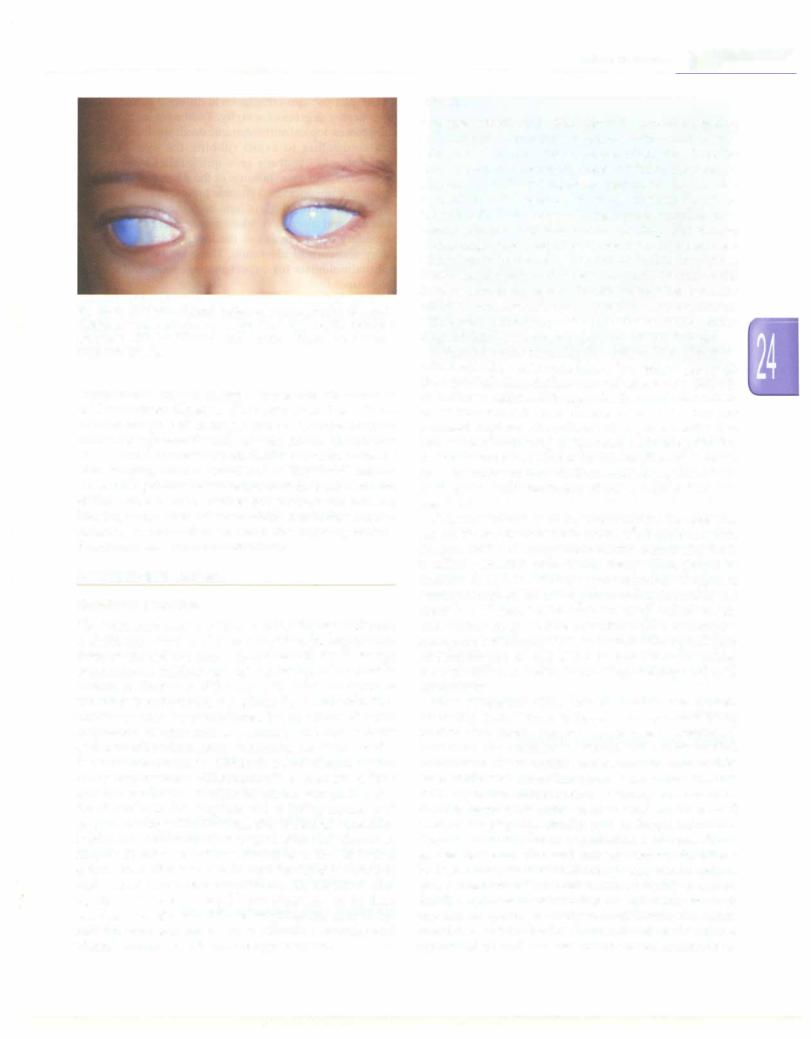

Benign tumorsincludedermoidsoforbit,lids oroncornea, hamartomas, osteoma, vascular malformations or heman giomas of various types and neurofibromas. Malignant intraocular tumors are confined to retinoblastoma (Fig. 24.3), juvenile xanthogranuloma, medulloepithe liomaandmetastatic lesions from neuroblastomas, Ewing sarcoma, leukemias and lymphomas. Orbital tumors includerhabdomyosarcoma, Langerhanscellhistiocytosis, extraocular spreadof retinoblastoma, metastatic spreadof Ewingsarcoma,neuroblastoma, leukemiaandlymphoma.

Refractive Errors

An abnormality in the refractive and focusing apparatus makes it difficultfor parallel rays of light from the distance

Fig. 24.3: 'Leukocoria' or white pupil in an infant secondary to retinoblastoma. Note the white appearance that appears to be from a structure located more posteriorly, has a slight yellowish pinkish tinge due to vascularization and has an appearance that is unlike that seen with to a cataract. Ultrasonography of the orbits helps confirm the diagnosis

to be accurately focused on the retina. This deviation from the normal emmetropic state is termed as 'ametropia' or refractive error. This manifests as poor or blurred vision which may be noticed by parents, relatives, friends, school teachers or reported by the child as a difficulty in viewing clearly. Sometimes, indirect evidence is reported as eye rubbing, 'squinting', 'going too close to the television' or holdingobjectstooclosetotheeyes. Anassessment of visual acuity is followed by cycloplegic refraction; fundus evaluation is required in addition to routine ophthalmic evaluation.Refractiveerrorsinclude myopia,hypermetropia and astigmatism, and spectacles must be prescribed accordingly. Associated amblyopia or strabismus must be taken care of and any additional features like nystagmus or extraocularmuscle imbalance ruled out. Patients needto be carefully counseled with respect to improvement of vision with spectacles and need for compliance with followup. Failure to show an improvement of vision warrants investigations to rule out any associated subtle pathology such as microstrabismus, retinal macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, congenital hereditary cone dystrophy, delayed visual maturation, dyslexia or Leber amaurosis.

Strabismus and Amblyopia

Strabismus is defined as the condition when the visual axes of the two eyes do not meet at the point of regard. In other words, the motor and sensory alignment of the two eyes and their images in the brain are not synchronized.

The cause may be a basic abnormality of development as in essential esotropia or exotropia (concomitant squint when the angle of deviation or separation of the two eyes is uniform, irrespective of thedirectionor positionof gaze) or secondarytoextraocularmuscle paralysis, e.g. paralytic squint, orbital space occupying lesion, myositis or orbital inflammationas in orbitalpseudoturnorsyndrome,orbital musculofascial abnormality like Duane retraction syn drome or Brown's superior oblique tendon sheath syndrome (causing an incomitant or nonconcomitant squint, where the deviation is more in certain positions and less or even absent in some positions of gaze).

An inward deviation of the eye is termed esotropia and outward deviation is termed exotropia. The child initially suffers diplopia due to the different images being pre-

|

|

|

s |

|

_____________ |

|

E s s en t ia P ed iat ric |

_____________ |

_ |

||

|

___ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

_______ |

|

|

|

||||

sented to the visual cortex by the two eyes, but learns to suppress one image, eventuallydevelopingamblyopiaor a 'lazy eye' with loss of binocularity and stereopsis. In very young children, the presence of an intermittent or constant squint or misalignment of the eyes should be indications for referral to an ophthalmologist.

Amblyopia or 'lazy eye' is a condition of subnormal vision defined as two lines less than normal or less than the fellow eye on the visual acuity chart with no anato mical cause detectable on examination, i.e. no media opacity and a normal fundus. Amblyogenic factors have theirmaximum impact ontheimmature developing visual system, i.e. during the first 6 yr of life and include sensory deprivationor abnormal binocularinteraction.The former would refer to a corneal opacity or cataract which, even if taken care of surgically, do not indicate good chances of restoration of normal vision. Similarly, abnormal bin ocular interaction occurs in the presence of strabismus or anisometropia (difference in the refractive power of the two eyes), inwhichcase one eye takesover and the visual cortical neurons meant to receive stimuli from the other eye are unable to develop normally, leading to a 'lazy eye'. These changes are potentially reversible with appropriate therapy in the first decade, but become irreversible and permanent later. Treatment involves restoration of vision with correction of refractive error, removal of media opacity if present (such as corneal opacity or cataract), patching therapy by part time patching of the 'good' eye to enable the 'lazy' eye to catchup, andstrabismussurgery to restore ocular alignment if required.

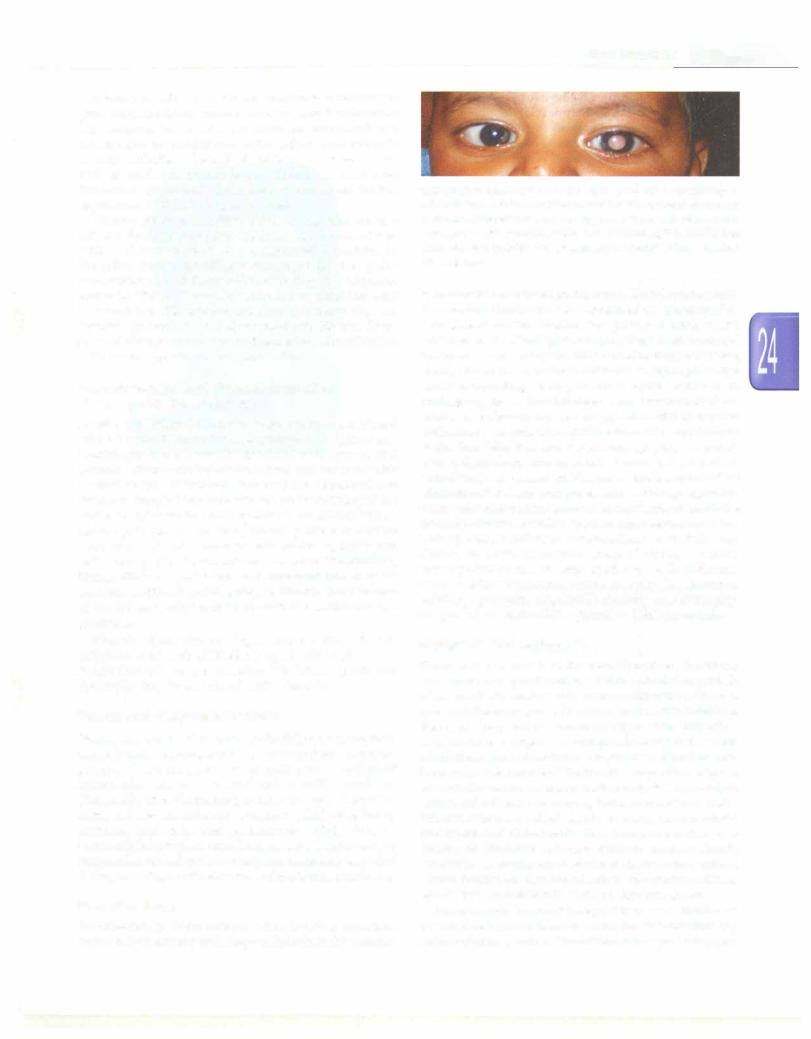

Cataract

A visible lenticular opacity in the eye is termed as a cataract. It is congenital if present since birth, develop mental if appearing later on, and traumatic if occuring after an episode of eye trauma. A central opacity is consi dered visually significant if it impairs visual acuity, and onclinicalassessmentobstructsa clearview of thefundus. A cataract may be unilateral or bilateral and symmetric or asymmetric. In view of the risk of sensory deprivation amblyopia, visually significant cataract should be treated surgically as soon as possible after birth. Functional success is highest if operated within the first few weeks after birth, provided the child is medically fit to undergo general anesthesia. Unilateral cataracts must be supple mented with postoperative patching therapy to take care of any amblyopic effect. Optical and visual rehabilitation for the aphakic state resulting from lens removal includes the implantation of an intraocular lens (IOL) for children above two years of age. Generally, intraocular lenses are avoided for children less than two years old as there are significant problemsofchangeinlens powerrequirements as the maximum growth of the eyeball takes place during the first two years of life and the risk of complications of glaucoma and intraocular inflammation and fibrosis are higher. In very young children, therefore, a capsule rim is

left for subsequent secondary IOL implantation, and temporary optical rehabilitation is provided with spectacles or contact lenses supplemented with patching for amblyopia in unilateral cases (Fig. 24.4).

Fig. 24.4: A child with bilateral developmental cataract. The cataract is partial and the condition was detected late. Also note that the child has a convergent squint. The child also has impaired hearing and congenital heart disease, suspected to be due to congenital rubella syndrome

Glaucoma

Primarycongenitalanddevelopmentaljuvenileglaucoma are now recognized to be inherited diseases. Primary congenitalglaucomaisassociatedwithCYPlBl gene, (2p21)

with apredominantlyautosomalrecessive mode ofinheri tance, and mutations in the myocillin (MYOC) gene.

Photophobia, blepharospasm, watering and an enlarged eyeball are classic symptoms. Suspicion of glaucoma or buphthalmos warrants urgent referral to an ophthal mologist. An examination under anesthesia is required to measurethecornealdiameterandintraocularpressure,and to visualize the optic disc. Once glaucoma is confirmed, medicaltherapyisstartedtolowerthepressureandpatient prepared for surgery.If the corneaisclearenoughto allow visualizationoftheanglestructures,agoniotomyisattemp ted.Iftheglaucomaismoresevereorthecorneaveryedema tous,adrainageprocedureisundertakentoopenalternative aqueous drainage channels such as trabeculectomy and trabeculotomy. If the cornea fails to clear after adequate controloftheintraocularpressure,cornealtransplantation isrequiredtorestorevisionandpreventirreversiblesensory deprivation amblyopia.

Children can also develop secondary glaucoma due to chronic use of topical corticosteroid eyedrops, following eye trauma particularly if associated with traumatic hyphema (blood in the anterior chamber) or angle

-------------------------------------E_y_e _D_i_s_o_rder s

recession, after surgery for developmental cataract and after chronic uveitis.

Eye Trauma and Related Problems

Eye injuries are common in children (Figs 24.SA and 8). Eye injuries are considered to be an important cause of preventable blindness. Effort must be made to educate the community in general, and mothers in particular, about the importance of not allowing childrento play with sharp pointed toys like bows and arrows, firecrackers, chemicals including colors during Holi festival or other chemicals like edible 'chuna'. Sharp and dangerous household objects like knives, scissors and needles, and chemicals like cleaning liquid, acid, whitewash paint and edible 'chuna' should be kept out of reach of children.

In case an injury is sustained, the eyes should be immediately washed thoroughly with locally available drinkable water, and the child should be rushed to the nearest hospital.

Perforating injuries of the globe require surgical repair under general anesthesia along with administration of systemic and topical antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis. The child should be told not to rub the eyes and given only fluids while rushing the child to hospital so that there is no unnecessary delay in preparing the patient for general anesthesia and planning surgery. Meticulous repair of the wounds is undertaken as soon as possible to minimize the risk of secondary complications such as endophthalrnitis, expulsion of intraocular contents and later risk of sympa thetic ophthalmitis or an inflammatory panuveitis in the normal eye due to sensitization of the immune system to the sequestered antigens in the exposed uveal tissue.

Retinal Diseases

Children may be affected by a wide variety of retinal diseases. Retinal detachment can occur secondary to trauma orspontaneously in cases with high or pathological myopia. Classical symptoms such as sudden loss of vision with floaters and photopsia may not be reported by children and the detachmentmay not be detected till much later. Retinal detachment requires surgical treatment and the sooner the surgery is performed, the greater are the chances of functionalrecoveryof vision. Otherdiseasesthat can affect the retina in childhood include degenerative and hereditary conditions like retinitis pigmentosa and different forms of macular degeneration such as Stargardt disease. These diseases lead to gradual, painless, bilateral diminution of vision in the first or second decade of life which may be accompanied by defective dark adaptation or abnormal color vision. No specific treatment modalities are available, but refractive correction, low vision aids, visual rehabilitation and genetic counseling are ancillary measures.

Fig. 24.SA: The sequelae of ocular trauma. Following injury with a wooden stick, the child had corneal perforation, which was repaired. Traumatic cataract was surgically removed. Note the irreversible anatomical damage with corneal scar, distorted iris and pupil and lens capsular opacification

Fig. 24.58: The sequelae of chemical injury, due to edible 'chuna'. Despite aggressive management, longterm sequelae include residual conjunctiva! inflammation with limbal stem cell deficiency and a scarred, irregular and opacified corneal surface

Vascular abnormalities of the retina such as heman giomas, arteriovenous malformations and exudative vitreoretinopathies like Coats disease may be seen. Retinal vasculitis may be seen in Eales disease and other inflam matory disorders. Diabetic retinopathy and hypertensive retinopathy can occur if these systemic disorders are present in sufficient grade of severity and for an adequate duration of time.

Suggested Reading

Sihota R, Tandon R. Parsons' diseases of the eye, 21st edn, 2011

Elsevier India, Delhj,

Skin Disorders

Neena Khanna, Seemab Rasool

Skin disorders account for nearly one-third of ailments in children. The prerequisite for dermatological diagnosis is identification of the different skin lesions as well as the various patterns formed by them.

BASIC PRINCIPLES

Morphology of Lesions

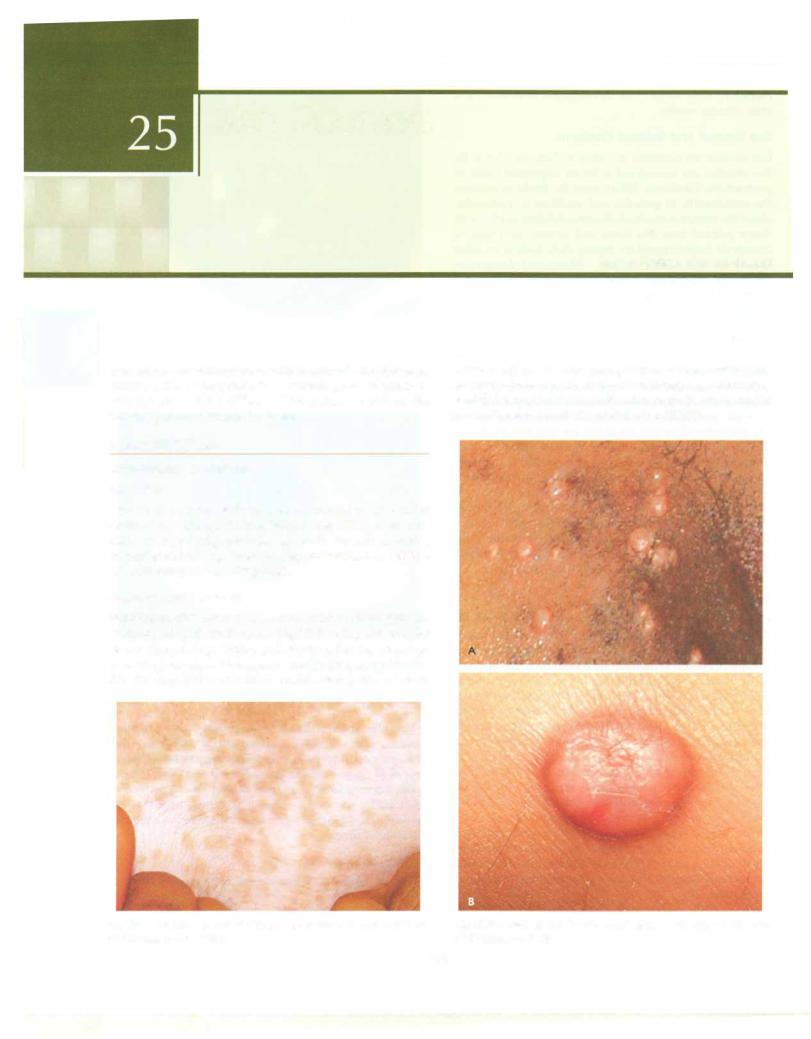

Macules

Macule is a circumscribed area of change in skin color without any change in consistency (Fig. 25.1). A macule may be hyperpigmented, e.g. cafe au lait macule, hypopigrnented, e.g. leprosy, depigrnented, e.g. vitiligo or erythematous, e.g. drug rash.

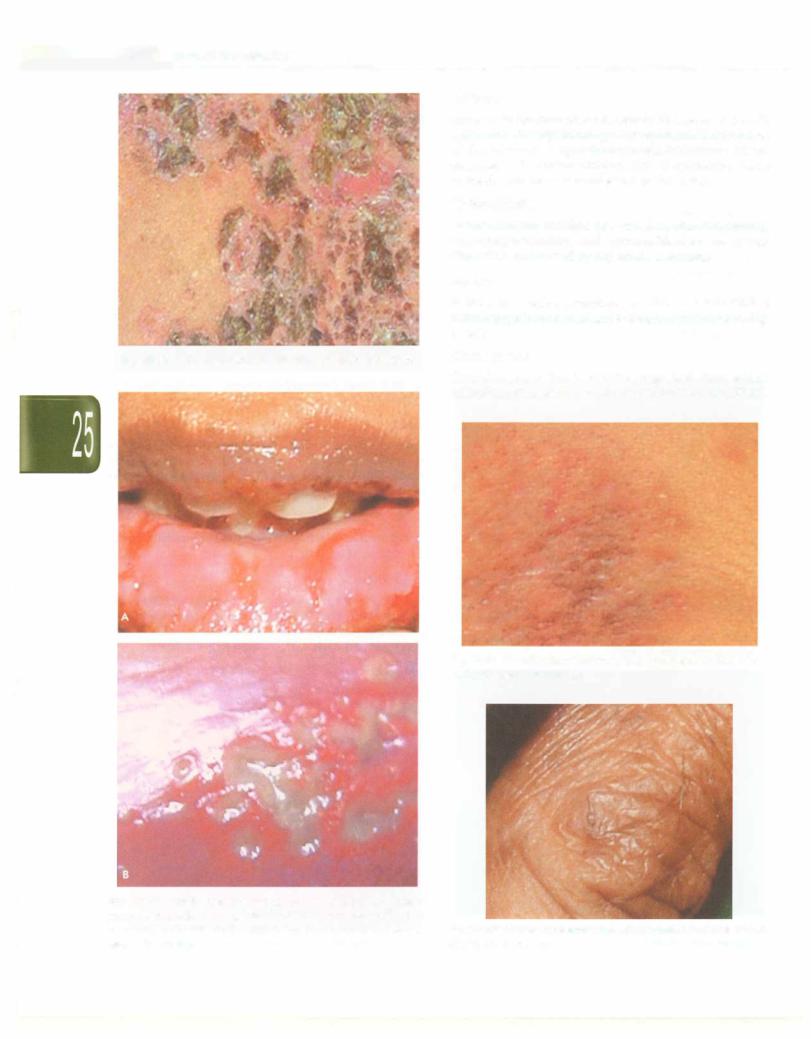

Papu/es and Nodules

Papule is a solid lesion< 0.5 cm in diameter with major part of it projecting above the skin (Fig. 25.2A). Papules may be dome shaped (e.g. trichoepithelioma), flat topped (e.g. verruca plana), conical (e.g. condyloma acuminata), filiform (e.g. filiform warts) or umblicated (with crater on

surface, e.g. molluscum contagiosum) or verrucous (with multiple closely packed firm elevations, e.g. verrucous warts). A papule which is >0.5 cm insizeand with the major part in the skin is called a nodule (Fig. 25.28).

Fig. 25.1: Macule, Circumscribed area ofchange in skin color without any change in consistency

Figs 25.2A and B: (A) Papule: Solid lesion, <0.5 cm; (B) Nodule: Solid lesion, >0.5 cm

672

--------------------------------------5-k_in__Disorders___

Plaque

Plaque is an area of altered skin consistency, the surface area of which is greater than its depth (Fig. 25.3). A plaque can be elevated, depressed or flat.

Wheal

Wheal, the characteristic lesion in urticaria, is an evanescent, pale or erythematous raised lesion which disappears within 24-48 hr (Fig. 25.4). Wheals are due to dermal edema, and when the edema extends into subcutis, they are called angioedema. When the wheals are linear, the phenomenon is called dermographism.

Blisters

Blister is a circumscribed elevated, superficial fluid filled cavity (Fig. 25.5). If <0.5 cm, it is a vesicle and if >0.5 cm, a bulla.

Fig. 25.3: Plaque: Area of altered skin consistency with a surface area of which is greater than its depth

Fig. 25.5: Blister: Circumscribed, elevated, superficial fluid filled I lesion

Scales

Scales are flakes of stratum corneum (Fig. 25.6) and are diagnostic in certain dermatoses, e.g. silver easily detachable flakes (psoriasis), branny (pityriasis versicolor) and fish-like scales ichthyosis).

Crusts

Crusts are formed when serum, blood or pus dries on the skin surface (Fig. 25.7).

Erosions and Ulcers

A defect, which involves only the epidermis and heals without a scar (Fig. 25.8A) is called an erosion, while an ulcer is a defect in the skin which extends into the dermis or deeper, and heals with scarring (Fig. 25.8B).

Fig. 25.4: Wheal: Evanescent, pale erythematous raised lesion which |

|

disappears within 24-48 hr |

Fig. 25.6: Scale: Flakes of stratum corneum |

|

E |

|

s |

|

______________ |

|

s s en t ial P ed iat ric |

_____________ |

_ |

||

|

__ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ |

______ |

|

|

|

||||

Atrophy

Atrophy is the reduction of some or all layers of skin. In epidermal atrophy, thinning of the epidermis leads to loss of skin texture and cigarette-paper like wrinkling without depression. In dermal atrophy, loss of connective tissue of the dermis leads to depression of the lesion.

Lichenification

Lichenification consists of a triad of skin thickening, hyperpigmentation and increased skin markings (Fig. 25.9). It is caused by repeated scratching.

Burrow

Burrow is a dark serpentine, curvilinear lesion with a minute papule at one end and is diagnostic of scabies (Fig. 25.10).

Fig. 25.7: Crust: Yellow brown collection of keratin and serum

Comedones

Comedones are due to keratin plugs that form within follicular ostia and they can be open or closed (Fig. 25.11).

Fig. 25.9: Lichenification, Thickening and hyperpigmentation of skin with increased skin markings

Figs 25.8A and B: Erosions and ulcers, (A) Erosions are due to complete or partial loss of epidermis with no loss of dermis; (B) ulcer is a defect in the skin which extends into the dermis or deeper and heals with scarring

Fig. 25.10: Burrow: Serpentine, thread-like, grayish curvilinear lesion, diagnostic of scabies