Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfchest wall and jugular veins. The patient may also experience substernal, neck, shoulder, or lower back pain, possibly with paresthesia or neuralgia.

Special Considerations

Because tracheal deviation usually signals a severe underlying disorder that can cause respiratory distress at any time, monitor the patient’s respiratory and cardiac status constantly, and make sure that emergency equipment is readily available. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as chest X- rays, bronchoscopy, an electrocardiogram, and arterial blood gas analysis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to perform coughing and deep breathing exercises, and explain which signs and symptoms of respiratory difficulty to report.

Pediatric Pointers

Keep in mind that respiratory distress typically develops more rapidly in children than in adults.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, tracheal deviation to the right commonly stems from an elongated, atherosclerotic aortic arch, but this deviation isn’t considered abnormal.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Tracheal Tugging[Cardarelli’s Sign, Castellino’s

Sign, Oliver’s Sign]

A visible recession of the larynx and trachea that occurs in synchrony with cardiac systole, tracheal tugging commonly results from an aneurysm or a tumor near the aortic arch and may signal dangerous compression or obstruction of major airways. The tugging movement, best observed with the patient’s neck hyperextended, reflects abnormal transmission of aortic pulsations because of compression and distortion of the heart, esophagus, great vessels, airways, and nerves.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you observe tracheal tugging, examine the patient for signs of respiratory distress, such as tachypnea, stridor, accessory muscle use, cyanosis, and agitation. If the patient is in distress, check airway patency. Administer oxygen, and prepare to intubate the patient if necessary. Insert an I.V. line for fluid and drug access, and begin cardiac monitoring.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, obtain a pertinent history. Ask about associated symptoms, especially pain, and about history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, chest surgery, or trauma.

Then examine the patient’s neck and chest for abnormalities. Palpate the neck for masses, enlarged lymph nodes, abnormal arterial pulsations, and tracheal deviation. Percuss and auscultate the lung fields for abnormal sounds, auscultate the heart for murmurs, and auscultate the neck and chest for bruits. Palpate the chest for a thrill.

Medical Causes

Aortic arch aneurysm. A large aneurysm can distort and compress surrounding tissues and structures, producing tracheal tugging. The cardinal sign of this aneurysm is severe pain in the substernal area, sometimes radiating to the back or side of the chest. A sudden increase in pain may herald impending rupture — a medical emergency. Depending on the aneurysm’s site and size, associated findings may include a visible pulsatile mass in the first or second intercostal space or suprasternal notch, a diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation, and an aortic systolic murmur and thrill in the absence of any peripheral signs of aortic stenosis. Dyspnea and stridor may occur with hoarseness, dysphagia, brassy cough, and hemoptysis. Jugular vein distention may also develop along with edema of the face, neck, or arm. Compression of the left main bronchus can cause atelectasis of the left lung.

Hodgkin’s disease. A tumor that develops adjacent to the aortic arch can cause tracheal tugging. Initial signs and symptoms include usually painless cervical lymphadenopathy, sustained or remittent fever, fatigue, malaise, pruritus, night sweats, and weight loss. Swollen lymph nodes may become tender and painful. Later findings include dyspnea and stridor; dry cough; dysphagia; jugular vein distention; edema of the face, neck, or arm; hepatosplenomegaly; hyperpigmentation, jaundice, or pallor; and neuralgia.

Thymoma. Thymoma is a rare tumor that can cause tracheal tugging if it develops in the anterior mediastinum. Cough, chest pain, dysphagia, dyspnea, hoarseness, a palpable neck mass, jugular vein distention, and edema of the face, neck, or upper arm are common findings.

Special Considerations

Place the patient in semi-Fowler’s position to ease respiration. Administer a cough suppressant and prescribed pain medications, but be alert for signs of respiratory depression.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic procedures, which may include chest X-rays, computed tomography scan, lymphangiography, aortography, bone marrow biopsy, liver biopsy, echocardiography, and a complete blood count.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the disorder and its treatment options. Discuss which positions will help ease the patient’s breathing.

Pediatric Pointers

In infants and children, tracheal tugging may indicate a mediastinal tumor, as occurs in Hodgkin’s

disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This sign may also occur in Marfan’s syndrome.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Tremors

The most common type of involuntary muscle movement, tremors are regular rhythmic oscillations that result from alternating contraction of opposing muscle groups. They’re typical signs of extrapyramidal or cerebellar disorders and can also result from certain drugs.

Tremors can be characterized by their location, amplitude, and frequency. They’re classified as resting, intention, or postural. Resting tremors occur when an extremity is at rest and subside with movement. They include the classic pill-rolling tremor of Parkinson’s disease. Conversely, intention tremors occur only with movement and subside with rest. Postural (or action) tremors appear when an extremity or the trunk is actively held in a particular posture or position. A common type of postural tremor is called an essential tremor.

Tremor-like movements may also be elicited, such as asterixis — the characteristic flapping tremor seen in hepatic failure. (See Asterixis, pages 70 to 72.)

Stress or emotional upset tends to aggravate a tremor. Alcohol commonly diminishes postural tremors.

History and Physical Examination

Begin the patient history by asking the patient about the tremor’s onset (sudden or gradual) and about its duration, progression, and any aggravating or alleviating factors. Does the tremor interfere with the patient’s normal activities? Does he have other symptoms? Ask the patient and his family and friends about behavioral changes or memory loss.

Explore the patient’s personal and family medical history for a neurologic (especially seizures), endocrine, or metabolic disorder. Obtain a complete drug history, noting especially the use of phenothiazines. Also, ask about alcohol use.

Assess the patient’s overall appearance and demeanor, noting mental status. Test range of motion and strength in all major muscle groups while observing for chorea, athetosis, dystonia, and other involuntary movements. Check deep tendon reflexes and, if possible, observe the patient’s gait.

Medical Causes

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Acute alcohol withdrawal after long-term dependence may first be manifested by resting and intention tremors that appear as soon as 7 hours after the last drink and progressively worsen. Other early signs and symptoms include diaphoresis, tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, anxiety, restlessness, irritability, insomnia, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Severe withdrawal may produce profound tremors, agitation, confusion,

hallucinations, and, possibly, seizures.

Alkalosis. Severe alkalosis may produce a severe intention tremor along with twitching, carpopedal spasms, agitation, diaphoresis, and hyperventilation. The patient may complain of dizziness, tinnitus, palpitations, and peripheral and circumoral paresthesia.

Benign familial essential tremor. Benign familial essential tremor, a tremor of early adulthood, produces a bilateral essential tremor that typically begins in the fingers and hands and may spread to the head, jaw, lips, and tongue. Laryngeal involvement may result in a quavering voice.

Cerebellar tumor. An intention tremor is a cardinal sign of cerebellar tumor; related findings may include ataxia, nystagmus, incoordination, muscle weakness and atrophy, and hypoactive or absent deep tendon reflexes.

Graves’ disease. Fine tremors of the hand, nervousness, weight loss, fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, and increased heat intolerance are some of the typical signs of Graves’ disease. It’s also characterized by an enlarged thyroid (goiter) and exophthalmos.

Hypercapnia. Elevated partial pressure of carbon dioxide may result in a rapid, fine intention tremor. Other common findings include headache, fatigue, blurred vision, weakness, lethargy, and decreasing level of consciousness (LOC).

Hypoglycemia. Acute hypoglycemia may produce a rapid, fine intention tremor accompanied by confusion, weakness, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cool, clammy skin. Early patient complaints typically include mild generalized headache, profound hunger, nervousness, and blurred or double vision. The tremor may disappear as hypoglycemia worsens and hypotonia and decreased LOC become evident.

Multiple sclerosis (MS). An intention tremor that waxes and wanes may be an early sign of MS. Commonly, visual and sensory impairments are the earliest findings. Associated effects vary greatly and may include nystagmus, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, ataxic gait, dysphagia, and dysarthria. Constipation, urinary frequency and urgency, incontinence, impotence, and emotional lability may also occur.

Parkinson’s disease. Tremors, a classic early sign of Parkinson’s disease, usually begin in the fingers and may eventually affect the foot, eyelids, jaw, lips, and tongue. The slow, regular, rhythmic resting tremor takes the form of flexion-extension or abduction-adduction of the fingers or hand, or pronation-supination of the hand. Flexion-extension of the fingers combined with abduction-adduction of the thumb yields the characteristic pill-rolling tremor.

Leg involvement produces flexion-extension foot movement. Lightly closing the eyelids causes them to flutter. The jaw may move up and down, and the lips may purse. The tongue, when protruded, may move in and out of the mouth in tempo with tremors elsewhere in the body. The rate of the tremor holds constant over time, but its amplitude varies.

Other characteristic findings include cogwheel or lead-pipe rigidity, bradykinesia, propulsive gait with forward-leaning posture, monotone voice, masklike facies, drooling, dysphagia, dysarthria, and occasionally oculogyric crisis (eyes fix upward, with involuntary tonic movements) or blepharospasm (eyelids close completely).

Thalamic syndrome. Central midbrain syndromes are heralded by contralateral ataxic tremors and other abnormal movements, along with Weber’s syndrome (oculomotor palsy with contralateral hemiplegia), paralysis of vertical gaze, and stupor or coma.

Anteromedial-inferior thalamic syndrome produces varying combinations of tremor, deep sensory loss, and hemiataxia. However, the main effect of this syndrome may be an

extrapyramidal dysfunction, such as hemiballismus or hemichoreoathetosis.

Thyrotoxicosis. Neuromuscular effects of thyrotoxicosis include a rapid, fine intention tremor of the hands and tongue, along with clonus, hyperreflexia, and Babinski’s reflex. Other common signs and symptoms include tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, palpitations, anxiety, dyspnea, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, an enlarged thyroid, and, possibly, exophthalmos.

Wernicke’s disease. An intention tremor is an early sign of Wernicke’s disease — a thiamine deficiency. Other features include ocular abnormalities (such as gaze paralysis and nystagmus), ataxia, apathy, and confusion. Orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia may also develop.

West Nile encephalitis. This brain infection is caused by West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus endemic to Africa, the Middle East, western Asia, and the United States. Mild infections are common and include fever, headache, and body aches, commonly accompanied by rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infections are marked by headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional seizures, paralysis, and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

Drugs. Phenothiazines (particularly piperazine derivatives such as fluphenazine) and other antipsychotics may cause resting and pill-rolling tremors. Infrequently, metoclopramide and metyrosine also cause these tremors. Lithium toxicity, sympathomimetics (such as terbutaline and pseudoephedrine), amphetamines, and phenytoin can all cause tremors that disappear with dose reduction.

Special Considerations

Severe intention tremors may interfere with the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living. Assist the patient with these activities as necessary, and take precautions against possible injury during such activities as walking or eating.

Patient Counseling

Reinforce the patient’s independence, and instruct him in the use of assistive devices as needed.

Pediatric Pointers

A normal neonate may display coarse tremors with stiffening — an exaggerated hypocalcemic startle reflex — in response to noises and chills. Pediatric-specific causes of pathologic tremors include cerebral palsy, fetal alcohol syndrome, and maternal drug addiction.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Tunnel Vision[Gun Barrel Vision, Tubular Vision]

Resulting from severe constriction of the visual field that leaves only a small central area of sight, tunnel vision is typically described as the sensation of looking through a tunnel or gun barrel. It may be unilateral or bilateral and usually develops gradually. (See Comparing Tunnel Vision with Normal Vision .) This abnormality can result from chronic open-angle glaucoma or advanced retinal degeneration. Tunnel vision may also result from laser photocoagulation therapy, which aims to correct retinal detachment. Also a common complaint of malingerers, tunnel vision can be verified or discounted by visual field examination performed by an ophthalmologist.

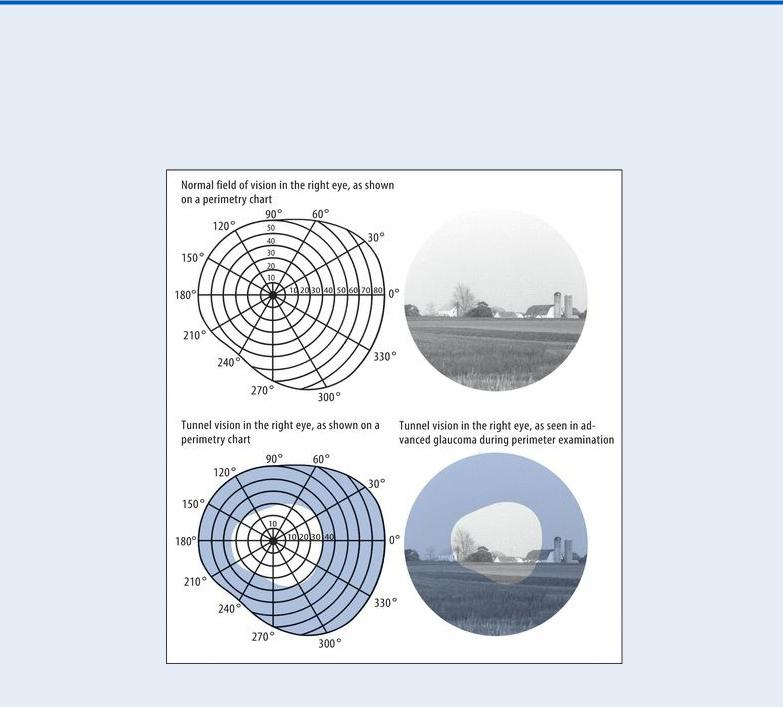

Comparing Tunnel Vision with Normal Vision

The patient with tunnel vision experiences drastic constriction of his peripheral visual field. The illustrations here convey the extent of this constriction, comparing test findings for normal and tunnel vision.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed a loss of peripheral vision, and have him describe the progression of vision loss. Ask him to describe in detail exactly what and how far he can see peripherally. Explore the patient’s personal and family history for ocular problems, especially progressive blindness that began at an early age.

To rule out malingering, observe the patient as he walks. A patient with severely limited peripheral vision typically bumps into objects (and may even have bruises), whereas the malingerer manages to avoid them.

If your examination findings suggest tunnel vision, refer the patient to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation.

Medical Causes

Chronic open-angle glaucoma. With chronic open-angle glaucoma, bilateral tunnel vision occurs late and slowly progresses to complete blindness. Other late findings include mild eye pain, halo vision, and reduced visual acuity (especially at night) that isn’t correctable with glasses.

Retinal pigmentary degeneration. Retinal pigmentary degeneration disorders, a group of hereditary disorders such as retinitis pigmentosa, produces an annular scotoma that progresses concentrically, causing tunnel vision and eventually resulting in complete blindness, usually by age 50. Impaired night vision, the earliest symptom, typically appears during the first or second decade of life. An ophthalmoscopic examination may reveal narrowed retinal blood vessels and a pale optic disc.

Special Considerations

To protect the patient from injury, be sure to remove all potentially dangerous objects and orient him to his surroundings. Because vision impairment is frightening, reassure the patient, and clearly explain diagnostic procedures, such as tonometry, perimeter examination, and visual field testing.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to compensate for tunnel vision and avoid bumping into objects.

Pediatric Pointers

In children with retinitis pigmentosa, night blindness foreshadows tunnel vision, which usually doesn’t develop until later in the disease process.

REFERENCES

Biswas, J. , Krishnakumar, S., & Ahuja, S. (2010) . Manual of ocular pathology. New Delhi, India: Jaypee—Highlights Medical Publishers.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

U

Urethral Discharge

This excretion from the urinary meatus may be purulent, mucoid, or thin; sanguineous or clear; and scant or profuse. It usually develops suddenly, most commonly in men with a prostate infection.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed the discharge, and have him describe its color, consistency, and quantity. Does he experience pain or burning on urination? Does he have difficulty initiating a urine stream? Does he experience urinary frequency? Ask the patient about other associated signs and symptoms, such as fever, chills, and perineal fullness. Explore his history for prostate problems, sexually transmitted disease, or urinary tract infection. Ask the patient if he has had recent sexual contacts or a new sexual partner.

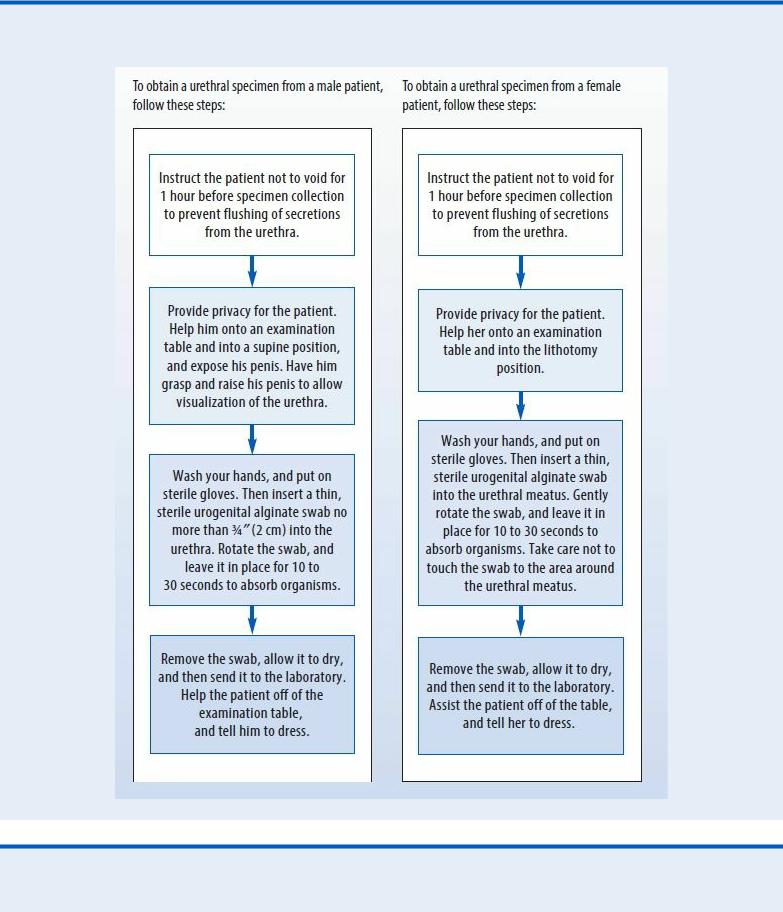

Inspect the patient’s urethral meatus for inflammation and swelling. Using proper technique, obtain a culture specimen. (See Collecting a Urethral Discharge Specimen .) Then, obtain a urine sample for urinalysis, culture, and possibly a three-glass urine sample. (See Performing the ThreeGlass Urine Test, page 714.) In the male patient, the prostate gland may have to be palpated.

Medical Causes

Prostatitis. Acute prostatitis is characterized by purulent urethral discharge. Initial signs and symptoms include sudden fever, chills, lower back pain, myalgia, perineal fullness, and arthralgia. Urination becomes increasingly frequent and urgent, and the urine may appear cloudy. Dysuria, nocturia, and some degree of urinary obstruction may also occur. The prostate may be tense, boggy, tender, and warm. Prostate massage to obtain prostatic fluid is contraindicated.

Chronic prostatitis, although often asymptomatic, may produce a persistent urethral discharge that’s thin, milky, or clear and sometimes sticky. The discharge appears at the meatus after a long interval between voidings, as in the morning. Associated effects include a dull aching in the prostate or rectum, sexual dysfunction such as ejaculatory pain, and urinary disturbances such as frequency, urgency, and dysuria.

Reiter’s syndrome. In Reiter’s syndrome — a self-limiting syndrome that usually affects males

— urethral discharge and other signs of acute urethritis occur 1 to 2 weeks after sexual contact. Asymmetrical arthritis, conjunctivitis of one or both eyes, and ulcerations on the oral mucosa, glans penis, palms, and soles may also occur with Reiter’s syndrome.

Urethritis. Urethritis, which is usually sexually transmitted (as in gonorrhea), commonly produces scant or profuse urethral discharge that’s thin and clear, mucoid, or thick and purulent. Other effects include urinary hesitancy, urgency, and frequency; dysuria; and itching and burning around the meatus.

Special Considerations

To relieve prostatitis symptoms, suggest that the patient take hot sitz baths several times daily, increase his fluid intake, void frequently, and avoid caffeine, tea, and alcohol. Monitor him for urine retention.

Collecting a Urethral Discharge Specimen

Performing the Three-Glass Urine Test

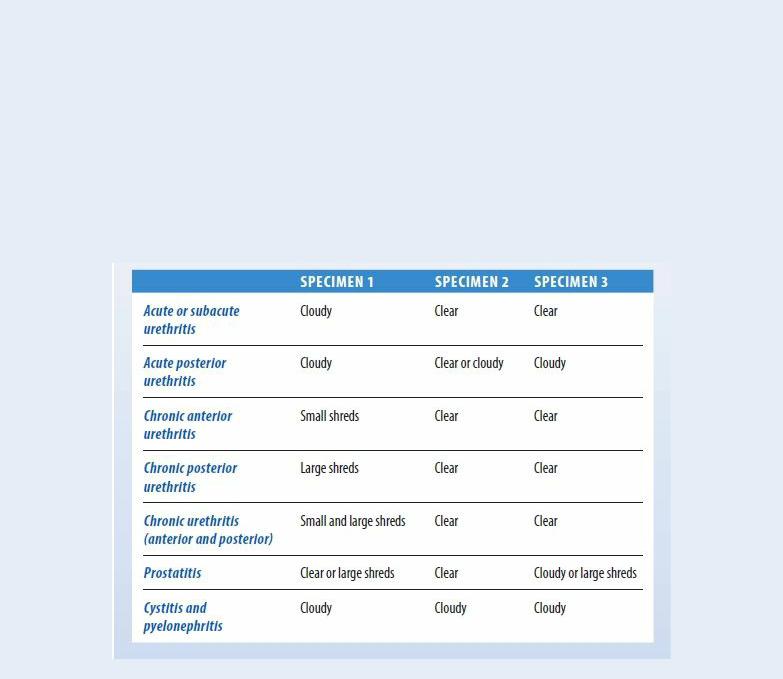

If your male patient complains of urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, flank or lower back pain, or other signs or symptoms of urethritis, and if his urine specimen is cloudy, perform the three-glass urine test.

First, ask him to void into three conical glasses labeled with numbers 1, 2, and 3. Firstvoided urine goes into glass #1, midstream urine into glass #2, and the remainder into glass #3. Tell the patient to avoid interrupting the stream of urine when shifting glasses, if possible.

Next, observe each glass for pus and mucus shreds. Also, note urine color and odor. Glass #1 will contain matter from the anterior urethra; glass #2, matter from the bladder; and glass #3, sediment from the prostate and seminal vesicles.

Some common findings are shown here. However, confirming diagnosis requires microscopic examination and a bacteriology report.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient with acute prostatitis about the importance of avoiding sexual activity until acute symptoms subside. Conversely, explain to the patient with chronic prostatitis that symptoms may be relieved by engaging in regular sexual activity.

Pediatric Pointers

Carefully evaluate a child with urethral discharge for evidence of sexual and physical abuse.

Geriatric Pointers

Urethral discharge in elderly males isn’t usually related to a sexually transmitted disease.

Reference