Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfSpecial Considerations

Closely monitor the patient after the seizure for recurring seizure activity. Prepare him for a computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging and EEG.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient’s family how to observe and record seizure activity, and explain the reasons for doing so. Emphasize the importance of compliance with drug therapy and follow-up, and explain possible adverse reactions to prescribed medications. Advise the patient to carry medical identification at all times.

Pediatric Pointers

Generalized seizures are common in children. In fact, between 75% and 90% of epileptic patients experience their first seizure before age 20. Many children between ages 3 months and 3 years experience generalized seizures associated with a fever; some of these children later develop seizures without a fever. Generalized seizures may also stem from inborn errors of metabolism, perinatal injury, brain infection, Reye’s syndrome, Sturge-Weber syndrome, arteriovenous malformation, lead poisoning, hypoglycemia, and idiopathic causes. The pertussis component of the DPT vaccine may cause seizures; however, this is rare.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Seizures, Simple Partial

Resulting from an irritable focus in the cerebral cortex, simple partial seizures typically last about 30 seconds and don’t alter the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). The type and pattern reflect the location of the irritable focus. Simple partial seizures may be classified as motor (including jacksonian seizures and epilepsia partialis continua) or somatosensory (including visual, olfactory, and auditory seizures).

A focal motor seizure is a series of unilateral clonic (muscle jerking) and tonic (muscle stiffening) movements of one part of the body. The patient’s head and eyes characteristically turn away from the hemispheric focus — usually the frontal lobe near the motor strip. A tonic-clonic contraction of the trunk or extremities may follow.

A Jacksonian motor seizure typically begins with a tonic contraction of a finger, the corner of the mouth, or one foot. Clonic movements follow, spreading to other muscles on the same side of the body, moving up the arm or leg, and eventually involving the whole side. Alternatively, clonic movements may spread to the opposite side, becoming generalized and leading to loss of consciousness. In the postictal phase, the patient may experience paralysis (Todd’s paralysis) in the

affected limbs, usually resolving within 24 hours.

Epilepsia partialis continua causes clonic twitching of one muscle group, usually in the face, arm, or leg. Twitching occurs every few seconds and persists for hours, days, or months without spreading. Spasms usually affect the distal arm and leg muscles more than the proximal ones; in the face, they affect the corner of the mouth, one or both eyelids, and, occasionally, the neck or trunk muscles unilaterally.

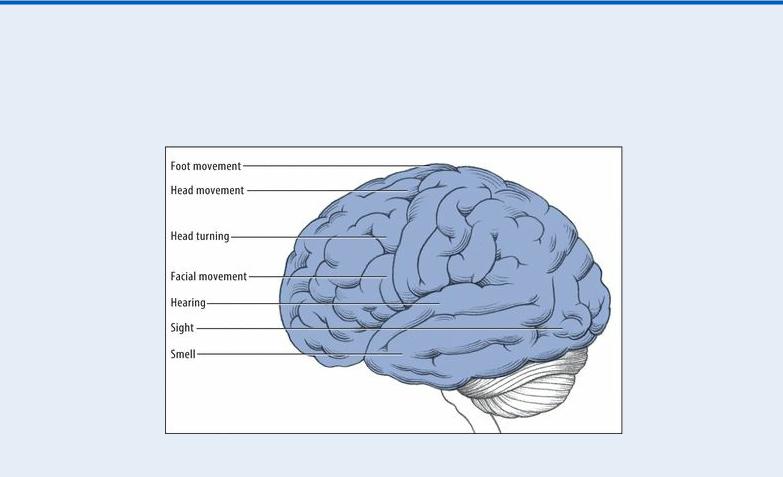

Body Functions Affected by Focal Seizures

The site of the irritable focus determines which body functions are affected by a focal seizure, as shown in the illustration below.

A focal somatosensory seizure affects a localized body area on one side. Usually, this type of seizure initially causes numbness, tingling, or crawling or “electric” sensations; occasionally, it causes pain or burning sensations in the lips, fingers, or toes. A visual seizure involves sensations of darkness or of stationary or moving lights or spots, usually red at first, then blue, green, and yellow. It can affect both visual fields or the visual field on the side opposite the lesion. The irritable focus is in the occipital lobe. In contrast, the irritable focus in an auditory or olfactory seizure is in the temporal lobe. (See Body Functions Affected by Focal Seizures.)

History and Physical Examination

Make sure to record the patient’s seizure activity in detail; your data may be critical in locating the lesion in the brain. Does the patient turn his head and eyes? If so, to what side? Where does movement first start? Does it spread? Because a partial seizure may become generalized, you’ll need to watch closely for loss of consciousness, bilateral tonicity and clonicity, cyanosis, tongue biting, and urinary incontinence. (See Seizures, Generalized Tonic-Clonic, pages 652 to 657.)

After the seizure, ask the patient to describe exactly what he remembers, if anything, about the seizure. Check the patient’s LOC, and test for residual deficits (such as weakness in the involved

extremity) and sensory disturbances.

Then, obtain a history. Ask the patient what happened before the seizure. Can he describe an aura or did he recognize its onset? If so, how — by a smell, a visual disturbance, or a sound or visceral phenomenon such as an unusual sensation in his stomach? How does this seizure compare with others he has had?

Also, explore fully any history — recent or remote — of head trauma. Check for a history of stroke or recent infection, especially with a fever, headache, or stiff neck.

Medical Causes

Brain abscess. Seizures can occur in the acute stage of abscess formation or after resolution of the abscess. A decreased LOC varies from drowsiness to deep stupor. Early signs and symptoms reflect increased intracranial pressure and include a constant, intractable headache; nausea; and vomiting. Later signs and symptoms include ocular disturbances, such as nystagmus, decreased visual acuity, and unequal pupils. Other findings vary according to the abscess site and may include aphasia, hemiparesis, and personality changes.

Brain tumor. Focal seizures are commonly the earliest indicators of a brain tumor. The patient may report a morning headache, dizziness, confusion, vision loss, and motor and sensory disturbances. He may also develop aphasia, generalized seizures, ataxia, a decreased LOC, papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, and widening pulse pressure. Eventually, he may assume a decorticate posture.

Head trauma. Any head injury can cause seizures, but penetrating wounds are characteristically associated with focal seizures. The seizures usually begin 3 to 15 months after injury, decrease in frequency after several years, and eventually stop. The patient may develop generalized seizures and a decreased LOC that may progress to coma.

Stroke. A major cause of seizures in patients older than age 50, a stroke may induce focal seizures up to 6 months after its onset. Related effects depend on the type and extent of the stroke, but may include a decreased LOC, contralateral hemiplegia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, and aphasia. A stroke may also cause visual deficits, memory loss, poor judgment, personality changes, emotional lability, a headache, urinary incontinence or retention, and vomiting. It may result in generalized seizures.

Special Considerations

No emergency care is necessary during a focal seizure, unless it progresses to a generalized seizure. (See Seizures, Generalized Tonic-Clonic , pages 652 to 657.) However, to ensure patient safety, you should remain with the patient during the seizure and reassure him.

Prepare the patient for such diagnostic tests as a computed tomography scan and EEG.

Patient Counseling

Teach the family how to record seizures and the importance of maintaining a safe environment. Emphasize the importance of complying with the prescribed medication regimen. Advise the patient to carry medical identification at all times.

Pediatric Pointers

Affecting more children than adults, focal seizures are likely to spread and become generalized. They typically cause the eyes, or the head and eyes, to turn to the side; in neonates, they cause mouth twitching, staring, or both.

Focal seizures in children can result from hemiplegic cerebral palsy, head trauma, child abuse, arteriovenous malformation, or Sturge-Weber syndrome. About 25% of febrile seizures present as focal seizures.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Setting Sun Sign[Sunset eyes]

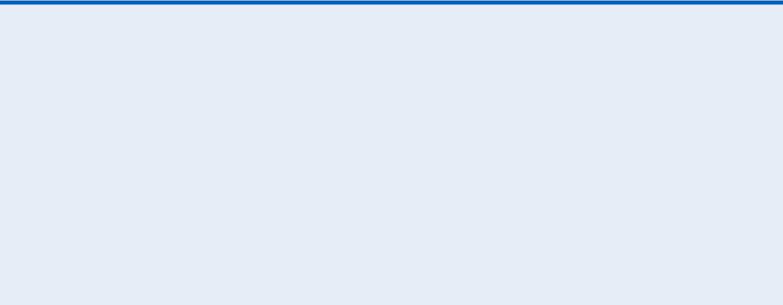

Setting sun sign refers to the downward deviation of an infant’s or a young child’s eyes as a result of pressure on cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. With this late and ominous sign of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), both eyes are rotated downward, typically revealing an area of sclera above the irises; occasionally, the irises appear to be forced outward. Pupils are sluggish, responding to light unequally. (See Identifying Setting Sun Sign.)

The infant with increased ICP is typically irritable and lethargic and feeds poorly. Changes in the level of consciousness (LOC), lower extremity spasticity, and opisthotonos may also be obvious. Increased ICP typically results from space-occupying lesions — such as tumors — or from an accumulation of fluid in the brain’s ventricular system, as occurs with hydrocephalus. It also results from intracranial bleeding or cerebral edema. Other signs include a globular appearance of the head (light bulb sign), a loss of upgaze, and distended scalp veins.

Setting sun sign may be intermittent — for example, it may disappear when the infant is upright because this position slightly reduces ICP. The sign may be elicited in a healthy infant younger than age 4 weeks by suddenly changing his head position, and in a healthy infant up to age 9 months by shining a bright light into his eyes and removing it quickly.

Identifying Setting Sun Sign

With this late sign of increased intracranial pressure in an infant or a young child, pressure on cranial nerves III, IV, and VI forces the eyes downward, revealing a rim of sclera above the irises.

History and Physical Examination

If you observe the setting sun sign in an infant, evaluate his neurologic status; then, obtain a brief history from his parents. Has the infant experienced a fall or even a minor trauma? When did this sign appear? Ask about early nonspecific signs of increasing ICP: Has the infant’s sucking reflex diminished? Is he irritable, restless, or unusually tired? Does he cry when moved? Is his cry high pitched? Has he vomited recently?

Next, perform a physical examination, keeping in mind that neurologic responses are primarily reflexive during early infancy. Assess the infant’s LOC. Is he awake, irritable, or lethargic? Keeping in mind his age and level of development, try to determine his ability to reach for a bright object or turn toward the sound of a music box. Observe his posture for normal flexion and extension or opisthotonos. Examine muscle tone, and observe for seizure automatisms.

Examine the infant’s anterior fontanelle for bulging, measure his head circumference and compare it to previous results, and observe his breathing pattern. (Cheyne-Stokes respirations may accompany increased ICP.) Also, check his pupillary response to light: Unilateral or bilateral dilation occurs as ICP rises. Finally, elicit reflexes that are diminished in increased ICP, especially Moro’s reflex. Keep endotracheal (ET) intubation equipment available.

Medical Causes

Increased ICP. Transient or intermittent setting sun sign usually occurs late in the infant with increased ICP. He may have bulging, widened fontanelles, an increased head circumference, and widened sutures. He may also exhibit a decreased LOC, behavioral changes, a high-pitched cry, pupillary abnormalities, and impaired motor movement as ICP increases. Other findings include increased systolic pressure, widened pulse pressure, bradycardia, changes in breathing pattern, vomiting, and seizures as ICP increases.

Special Considerations

Care of the infant with setting sun sign includes monitoring his vital signs and neurologic status. Elevate the head of the crib to at least 30 degrees, and monitor intake and output. Monitor ICP, restrict fluids, and insert an I.V. line to administer a diuretic. For severely increased ICP, ET intubation and mechanical hyperventilation may be required to reduce serum carbon dioxide levels and constrict cerebral vessels. Therapy to induce a barbiturate coma or hypothermia therapy may be required to lower the metabolic rate.

Try to maintain a calm environment and, when the infant cries, offer comfort to help prevent stress-related ICP elevations. Perform nursing duties judiciously because procedures may further increase ICP. Prepare the child and his family for surgical management of increased ICP and hydrocephalus, as appropriate. Encourage the parents’ help, and offer them emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the disorder and its treatment options. Orient the family to the care plan (surgical management of ICP and hydrocephalus) as appropriate.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Skin, Clammy

Clammy skin — moist, cool, and usually pale — is a sympathetic response to stress, which triggers release of the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine. These hormones cause cutaneous vasoconstriction and secretion of cold sweat from eccrine glands, particularly on the palms, forehead, and soles.

Clammy skin typically accompanies shock, acute hypoglycemia, anxiety reactions, arrhythmias, and heat exhaustion. It also occurs as a vasovagal reaction to severe pain associated with nausea, anorexia, epigastric distress, hyperpnea, tachypnea, weakness, confusion, tachycardia, and pupillary dilation or a combination of these findings. Marked bradycardia and syncope may follow.

History and Physical Examination

If you detect clammy skin, remember that rapid evaluation and intervention are paramount. (See Clammy Skin: A Key Finding.) Ask the patient if he has a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus or a cardiac disorder. Is he taking medications, especially an antiarrhythmic? Is he experiencing pain, chest pressure, nausea, or epigastric distress? Does he feel weak? Does he have a dry mouth? Does he have diarrhea or increased urination?

Next, examine the pupils for dilation. Also, check for abdominal distention and increased muscle tension.

Medical Causes

Anxiety. An acute anxiety attack commonly produces cold, clammy skin on the forehead, palms, and soles. Other features include pallor, a dry mouth, tachycardia or bradycardia, palpitations, and hypertension or hypotension. The patient may also develop tremors, breathlessness, a headache, muscle tension, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, diarrhea, increased urination, and sharp chest pain.

Arrhythmias. Cardiac arrhythmias may produce generalized cool, clammy skin along with mental status changes, dizziness, and hypotension.

Cardiogenic shock. Generalized cool, moist, pale skin accompanies confusion, restlessness, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, narrowing pulse pressure, cyanosis, and oliguria.

Heat exhaustion. In the acute stage of heat exhaustion, generalized cold, clammy skin accompanies an ashen appearance, a headache, confusion, syncope, giddiness, and, possibly, a subnormal temperature, with mild heat exhaustion. The patient may exhibit a rapid and thready pulse, nausea, vomiting, tachypnea, oliguria, thirst, muscle cramps, and hypotension.

Hypoglycemia (acute). Generalized cool, clammy skin or diaphoresis may accompany irritability, tremors, palpitations, hunger, a headache, tachycardia, and anxiety. Central nervous system disturbances include blurred vision, diplopia, confusion, motor weakness, hemiplegia, and coma. These signs and symptoms typically resolve after the patient is given glucose.

Hypovolemic shock. With hypovolemic shock, generalized pale, cold, clammy skin accompanies a subnormal body temperature, hypotension with narrowing pulse pressure, tachycardia, tachypnea, and a rapid, thready pulse. Other findings are flat neck veins, an increased capillary refill time, decreased urine output, confusion, and a decreased level of consciousness.

Septic shock. The cold shock stage causes generalized cold, clammy skin. Associated findings include a rapid and thready pulse, severe hypotension, persistent oliguria or anuria, and respiratory failure.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

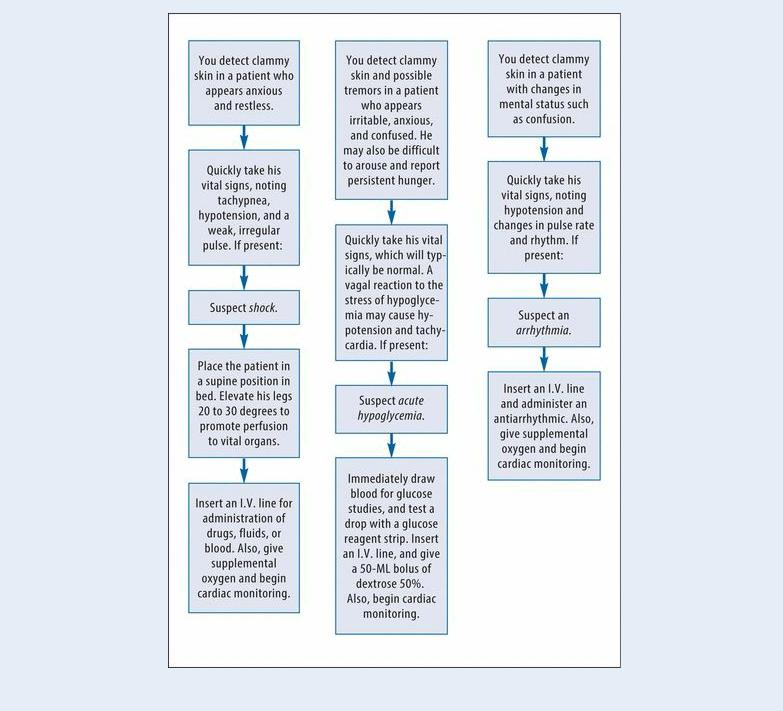

Clammy Skin: A Key Finding

Be alert for clammy skin because it commonly accompanies emergency conditions, such as shock, acute hypoglycemia, and arrhythmias. To know what to do, review these typical clinical situations.

Special Considerations

Take the patient’s vital signs frequently, and monitor urine output. If clammy skin occurs with an anxiety reaction or pain, offer the patient emotional support, administer pain medication, and provide a quiet environment.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying illness, and orient the patient and family to the intensive care unit, if applicable.

Pediatric Pointers

Infants in shock don’t have clammy skin because of their immature sweat glands.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients develop clammy skin easily because of decreased tissue perfusion. Always consider bowel ischemia in the differential diagnosis of older patients who present with cool, clammy skin — especially if abdominal pain or bloody stools occur.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Skin, Mottled

Mottled skin is patchy discoloration indicating primary or secondary changes of the deep, middle, or superficial dermal blood vessels. It can result from a hematologic, immune, or connective tissue disorder; chronic occlusive arterial disease; dysproteinemia; immobility; exposure to heat or cold; or shock. Mottled skin can be a normal reaction such as the diffuse mottling that occurs when exposure to cold causes venous stasis in cutaneous blood vessels (cutis marmorata).

Mottling that occurs with other signs and symptoms usually affects the extremities, typically indicating restricted blood flow. For example, livedo reticularis, a characteristic network pattern of reddish blue discoloration, occurs when vasospasm of the middermal blood vessels slows local blood flow in dilated superficial capillaries and small veins. Shock causes mottling from systemic vasoconstriction.

History and Physical Examination

Mottled skin may indicate an emergency condition requiring rapid evaluation and intervention. (See Mottled Skin: Knowing What to Do.) However, if the patient isn’t in distress, obtain a history. Ask if the mottling began suddenly or gradually. What precipitated it? How long has he had it? Does anything make it go away? Does the patient have other symptoms, such as pain, numbness, or tingling in an extremity? If so, do they disappear with temperature changes?

Observe the patient’s skin color, and palpate his arms and legs for skin texture, swelling, and temperature differences between extremities. Check the capillary refill time. Also, palpate for the presence (or absence) of pulses and for their quality. Note breaks in the skin, muscle appearance, and hair distribution. Also, assess motor and sensory function.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Mottled Skin: Knowing What to Do

If the patient’s skin is pale, cool, clammy, and mottled at the elbows and knees or all over, he may be developing hypovolemic shock. Quickly take his vital signs, and make sure to note

tachycardia or a weak, thready pulse. Observe the neck for flattened veins. Does the patient appear anxious? If you detect these signs and symptoms, place the patient in a supine position in bed with his legs elevated 20 to 30 degrees. Administer oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask, and begin cardiac monitoring. Insert a large-bore I.V. line for rapid fluid or blood product administration, and prepare to insert a central line or a pulmonary artery catheter. Also, prepare to catheterize the patient to monitor urine output.

Localized mottling in a pale, cool extremity that the patient says feels painful, numb, and tingling may signal acute arterial occlusion. Immediately check the patient’s distal pulses: If they’re absent or diminished, you’ll need to insert an I.V. line in an unaffected extremity, and prepare the patient for arteriography or immediate surgery.

Medical Causes

Acrocyanosis. With the rare disorder acrocyanosis, anxiety or exposure to cold can cause vasospasm in small cutaneous arterioles. This results in persistent symmetrical blue and red mottling of the affected hands, feet, and nose.

Arterial occlusion (acute). Initial signs of acute arterial occlusion include temperature and color changes. Pallor may change to blotchy cyanosis and livedo reticularis. Color and temperature demarcation develop at the level of obstruction. Other effects include sudden onset of pain in the extremity and, possibly, paresthesia, paresis, and a sensation of cold in the affected area. Examination reveals diminished or absent pulses, cool extremities, an increased capillary refill time, pallor, and diminished reflexes.

Arteriosclerosis obliterans. Atherosclerotic buildup narrows intra-arterial lumina, resulting in reduced blood flow through the affected artery. Obstructed blood flow to the extremities (most commonly the legs) produces such peripheral signs and symptoms as leg pallor, cyanosis, blotchy erythema, and livedo reticularis. Related findings include intermittent claudication (most common symptom), diminished or absent pedal pulses, and leg coolness. Other symptoms include coldness and paresthesia.

Buerger’s disease. Buerger’s disease, a form of vasculitis, produces unilateral or asymmetrical color changes and mottling, particularly livedo networking in the lower extremities. It also typically causes intermittent claudication and erythema along extremity blood vessels. During exposure to cold, the feet are cold, cyanotic, and numb; later they’re hot, red, and tingling. Other findings include impaired peripheral pulses and peripheral neuropathy. Buerger’s disease is typically exacerbated by smoking.

Cryoglobulinemia. Cryoglobulinemia is a necrotizing disorder that causes patchy livedo reticularis, petechiae, and ecchymoses. Other findings include a fever, chills, urticaria, melena, skin ulcers, epistaxis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, eye hemorrhages, hematuria, and gangrene.

Hypovolemic shock. Vasoconstriction from shock commonly produces skin mottling, initially in the knees and elbows. As shock worsens, mottling becomes generalized. Early signs include a sudden onset of pallor, cool skin, restlessness, thirst, tachypnea, and slight tachycardia. As shock progresses, associated findings include cool, clammy skin; a rapid, thready pulse; hypotension; narrowed pulse pressure; decreased urine output; subnormal temperature; confusion; and a decreased level of consciousness.

Livedo reticularis (idiopathic or primary). Symmetrical, diffuse mottling can involve the