Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Autoerythrocyte sensitivity. With autoerythrocyte sensitivity, painful ecchymoses appear either singly or in groups, usually preceded by local itching, burning, or pain. Common associated findings include epistaxis, hematuria, hematemesis, and menometrorrhagia. Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, syncope, a headache, and chest pain are also common.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC can cause varying degrees of purpura, depending on its severity and underlying cause. Rarely, the patient develops life-threatening purpura fulminans, with symmetrical cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions on the arms and legs. Or, he may have cutaneous oozing, hematemesis, or bleeding from incision or needle insertion sites. Other findings include acrocyanosis; nausea; dyspnea; seizures; severe muscle, back, and abdominal pain; and signs of acute tubular necrosis such as oliguria.

Dysproteinemias. With multiple myeloma, petechiae and ecchymoses accompany other bleeding tendencies: hematemesis, epistaxis, gum bleeding, and excessive bleeding after surgery. Similar findings occur with cryoglobulinemia, which may also produce malignant maculopapular purpura. Hyperglobulinemia typically begins insidiously with occasional outbreaks of purpura over the lower legs and feet. These outbreaks eventually become more frequent and extensive, involving the entire lower leg and possibly the trunk. The purpura usually occurs after prolonged standing or exercise and may be heralded by skin burning or stinging. Leg edema, knee or ankle pain, and a low-grade fever may precede or accompany the purpura, which gradually fades over 1 to 2 weeks. Persistent pigmentation develops after repeated outbreaks.

Easy bruising syndrome. Easy bruising syndrome is characterized by recurrent bruising on the legs, arms, and trunk, either spontaneously or following minor trauma. Bruising may be preceded by pain and is more common in women than in men, especially during menses.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). Besides petechiae, EDS is marked by easy bruising, epistaxis, gum bleeding, hematuria, melena, menorrhagia, and excessive bleeding after surgery. EDS characteristically produces soft, velvety, hyperelastic skin; hyperextensible joints; increased skin and blood vessel fragility; and repeated dislocations of the temporomandibular joint.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Chronic ITP typically begins insidiously, with scattered petechiae that are usually found on the distal arms and legs. Deep-lying ecchymoses may also occur. Other findings include epistaxis, easy bruising, hematuria, hematemesis, and menorrhagia.

Leukemia. Leukemia produces widespread petechiae on the skin, mucous membranes, retina, and serosal surfaces that persist throughout the course of the disease. Confluent ecchymoses are uncommon. The patient may also exhibit swollen and bleeding gums, epistaxis, and other bleeding tendencies. Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are common.

Acute leukemias also produce severe prostration and a high fever and may cause dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, and abdominal or bone pain. Confusion, a headache, seizures, vomiting, papilledema, and nuchal rigidity may occur late in the disease. Chronic leukemias begin insidiously with minor bleeding tendencies, malaise, fatigue, pallor, a low-grade fever, anorexia, and weight loss.

Myeloproliferative disorders. Myeloproliferative disorders, which include polycythemia vera, paradoxically can cause hemorrhage accompanied by ecchymoses and ruddy cyanosis. The oral mucosa takes on a deep purplish red hue, and slight trauma causes swollen gums to bleed. Other findings include pruritus, urticaria, and such nonspecific signs and symptoms as lethargy, weakness, fatigue, and weight loss. The patient typically complains of a headache, a sensation of fullness in the head, and rushing in the ears; dizziness and vertigo; dyspnea; paresthesia of the

fingers; double or blurred vision and scotoma; and epigastric distress. He may also experience intermittent claudication, hypertension, hepatosplenomegaly, and impaired mentation.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may produce purpura accompanied by other cutaneous findings, such as scaly patches on the scalp, face, neck, and arms; diffuse alopecia; telangiectasia; urticaria; and ulceration. The characteristic butterfly rash appears in the disorder’s acute phase. Common associated signs and symptoms include nondeforming joint pain and stiffness, Raynaud’s phenomenon, seizures, psychotic behavior, photosensitivity, a fever, anorexia, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Generalized purpura, hematuria, vaginal bleeding, jaundice, and pallor are among the usual presenting signs and symptoms in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Most patients have a fever, and some also experience fatigue, weakness, a headache, nausea, abdominal pain, arthralgia, and hepatosplenomegaly. Possible neurologic effects include seizures, paresthesia, cranial nerve palsies, vertigo, and an altered level of consciousness. Renal failure may also occur.

Trauma. Traumatic injury can cause local or widespread purpura.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Invasive procedures, such as venipuncture and arterial catheterization, may produce local ecchymoses and hematomas due to extravasated blood.

Drugs. The anticoagulants heparin and warfarin can produce purpura. Administration of warfarin can result in painful areas of erythema that become purpuric and then necrotic with an adherent black eschar. The lesions develop between the 3rd and 10th day of drug administration. Surgery and other procedures. Any procedure that disrupts circulation, coagulation, or platelet activity or production can cause purpura. These include pulmonary and cardiac surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hemodialysis, multiple blood transfusions with platelet-poor blood, and the use of plasma expanders such as dextran.

Special Considerations

Reassure the patient that purpuric lesions aren’t permanent and will fade if the underlying cause can be successfully treated. Warn him not to use cosmetic fade creams or other products in an attempt to reduce pigmentation. If he has a hematoma, apply pressure and cold compresses initially to help reduce bleeding and swelling. After the first 24 hours, apply hot compresses to help speed blood absorption.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests. These may include a peripheral blood smear, bone marrow examination, and blood tests to determine platelet count, bleeding and coagulation times, capillary fragility, clot retraction, one-stage prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen levels.

Patient Counseling

Reassure the patient that the purpuric lesions aren’t permanent and will fade if the underlying cause can be successfully treated. Warn the patient not to use fade creams as an attempt to reduce pigmentation.

Pediatric Pointers

Neonates commonly exhibit petechiae, particularly on the head, neck, and shoulders, after vertex deliveries. Thought to result from the trauma of birth, these petechiae disappear within a few days. Other causes in infants include thrombocytopenia, vitamin K deficiency, and infantile scurvy.

The most common type of purpura in children is allergic purpura. Other causes in children include trauma, hemophilia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Gaucher’s disease, thrombasthenia, congenital factor deficiencies, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, acute ITP, von Willebrand’s disease, and the rare but life-threatening purpura fulminans, which usually follows bacterial or viral infection.

As a child grows and tests his motor skills, the risk of accidents multiplies, and ecchymoses and hematomas commonly occur. However, when you assess a child with purpura, be alert for signs of possible child abuse: bruises in different stages of resolution, from repeated beatings; bruise patterns resembling a familiar object, such as a belt, hand, or thumb and finger; and bruises on the face, buttocks, or genitalia, areas unlikely to be injured accidentally.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Pustular Rash

A pustular rash is made up of crops of pustules — a visible collection of pus within or beneath the epidermis, commonly in a hair follicle or sweat pore. These lesions vary greatly in size and shape and can be generalized or localized to the hair follicles or sweat glands. (See Recognizing Common Skin Lesions, page 549.) Pustules can result from a skin or systemic disorder, the use of certain drugs, or exposure to a skin irritant. For example, people who’ve been swimming in salt water commonly develop a papulopustular rash under the bathing suit or elsewhere on the body from irritation by sea organisms. Although many pustular lesions are sterile, a pustular rash usually indicates an infection. A vesicular eruption, or even acute contact dermatitis, can become pustular if secondary infection occurs.

History and Physical Examination

Have the patient describe the appearance, location, and onset of the first pustular lesion. Did another type of skin lesion precede the pustule? Find out how the lesions spread. Ask what medications the patient takes and if he has applied topical medication to his rash. If so, what type and when did he last apply it? Find out if he has a family history of a skin disorder.

Examine the entire skin surface, noting if it’s dry, oily, moist, or greasy. Record the exact location and distribution of the skin lesions and their color, shape, and size.

Medical Causes

Acne vulgaris. Pustules typify inflammatory lesions of acne vulgaris, which is accompanied by papules, nodules, cysts, open comedones (blackheads), and closed (whiteheads) comedones. Lesions commonly appear on the face, shoulders, back, and chest. Other findings include pain on pressure, pruritus, and burning. Chronic recurrent lesions produce scars.

Blastomycosis. Blastomycosis is a fungal infection that produces small, painless, nonpruritic macules or papules that can enlarge to well-circumscribed, verrucous, crusted, or ulcerated lesions edged by pustules. Localized infection may cause only one lesion; systemic infection may cause many lesions on the hands, feet, face, and wrists. Blastomycosis also produces signs of pulmonary infection, such as pleuritic chest pain and a dry, hacking or productive cough with occasional hemoptysis.

Folliculitis. Folliculitis is a bacterial infection of hair follicles that produces individual pustules, each pierced by a hair and possibly accompanied by pruritus. “Hot tub” folliculitis produces pustules on areas covered by a bathing suit.

Furunculosis. A furuncle is an acute, deep-seated, red, hot, tender abscess that evolves from a staphylococcal folliculitis. Furuncles usually begin as small, tender red pustules at the base of hair follicles. They’re likely to occur on the face, neck, forearm, groin, axillae, buttocks, and legs or areas that are prone to repeated friction. The pustules usually remain tense for 2 to 4 days and then become fluctuant. Rupture discharges pus and necrotic material. Then, pain subsides, but erythema and edema may persist.

Impetigo contagiosa. Impetigo contagiosa, a vesiculopustular eruptive disorder that occurs in nonbullous and bullous forms, is usually caused by streptococci or staphylococci. Vesicles form and break, and a crust forms from the exudate: a thick, yellow crust in streptococcal impetigo and a thin, clear crust in staphylococcal impetigo. Both forms usually produce painless itching.

Monkey pox. A pustular rash with raised fluid-filled bumps that later become crusted, scab over, and fall off is characteristic of a monkey pox viral infection. Macular, papular, vesicular lesions can also occur with a monkey pox rash. Additionally, symptoms may include fever, headache, backache, lymphadenopathy, sore throat, cough, and fatigue.

Pustular miliaria. Pustular miliaria is an anhidrotic disorder that causes pustular lesions that begin as tiny erythematous papulovesicles located at sweat pores. Diffuse erythema may radiate from the lesion. The rash and associated burning and pruritus worsen with sweating.

Pustular psoriasis. Small vesicles form and eventually become pustules in pustular psoriasis. The patient may report pruritus, burning, and pain. Localized pustular psoriasis usually affects the hands and feet. Generalized pustular psoriasis may erupt suddenly in a patient with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or exfoliative psoriasis; although rare, this form of psoriasis can occasionally be fatal.

Rosacea. Rosacea is a chronic hyperemic disorder that commonly produces telangiectasia with acute episodes of pustules, papules, and edema. Characterized by persistent erythema, rosacea may begin as a flush covering the forehead, malar region, nose, and chin. Intermittent episodes gradually become more persistent, and the skin — instead of returning to its normal color — develops varying degrees of erythema.

Scabies. Threadlike channels or burrows under the skin characterize scabies, which can also produce pustules, vesicles, and excoriations. The lesions are a few millimeters long, with a swollen nodule or red papule that contains the itch mite.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

In men, crusted lesions commonly develop on the glans, shaft, and scrotum. In women, lesions may form on the nipples. In both genders, these lesions have a predilection for skin folds. Crusty excoriated lesions also develop on wrists, elbows, axillae, waistline, behind the knees, and ankles. Related pruritus worsens with inactivity and warmth.

Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms include a high fever, malaise, prostration, a severe headache, a backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust and, later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

Varicella zoster. When immunity to varicella declines, the virus reactivates along a dermatome, producing extremely painful and pruritic vesicles and pustules (herpes zoster, or shingles). Even with resolution of the rash, patients may experience chronic pain (postherpetic neuralgia) that may persist for months.

Other Causes

Drugs. Bromides and iodides commonly cause a pustular rash. Other drug causes include corticotropin, corticosteroids, dactinomycin, trimethadione, lithium, phenytoin, phenobarbital, isoniazid, hormonal contraceptives, androgens, and anabolic steroids.

Special Considerations

Observe wound and skin isolation procedures until infection is ruled out by a Gram stain or culture and sensitivity test of the pustule’s contents. If the organism is infectious, don’t allow drainage to touch unaffected skin. Instruct the patient to keep his bathroom articles and linens separate from those of other family members. Associated pain and itching, altered body image, and the stress of isolation may result in loss of sleep, anxiety, and depression. Give medications to relieve pain and itching, and encourage the patient to express his feelings.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the disorder, the treatment options, and methods to prevent the spread of infection. Provide emotional support and information about relieving pain and itching.

Pediatric Pointers

Among the various disorders that produce a pustular rash in children are varicella, erythema toxicum neonatorum, candidiasis, impetigo, infantile acropustulosis, and acrodermatitis enteropathica.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

R

Raccoon Eyes

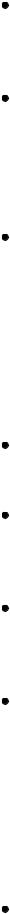

Raccoon eyes are bilateral periorbital ecchymoses that don’t result from facial soft tissue trauma. Usually an indicator of basilar skull fracture, this sign develops when damage at the time of fracture tears the meninges and causes the venous sinuses to bleed into the arachnoid villi and the cranial sinuses. Raccoon eyes may be the only indicator of a basilar skull fracture, which isn’t always visible on skull X-rays. Their appearance signals the need for careful assessment to detect underlying trauma because a basilar skull fracture can injure the cranial nerves, blood vessels, and brain stem. Raccoon eyes can also occur after a craniotomy if the surgery causes a meningeal tear.

History and Physical Examination

After raccoon eyes are detected, check the patient’s vital signs and try to find out when the head injury occurred and the nature of the head injury. (See Recognizing Raccoon Eyes, page 626.) Then, evaluate the extent of underlying trauma.

Start by evaluating the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) using the Glasgow Coma Scale. (See Glasgow Coma Scale, page 439.) Next, evaluate cranial nerve (CN) function, especially CN I (olfactory), III (oculomotor), IV (trochlear), VI (abducens), and VII (facial). Assess for signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure. If the patient’s condition permits, also test his visual acuity and gross hearing. Note irregularities in the facial or skull bones as well as swelling, localized pain, Battle’s sign, or face or scalp lacerations. Check for ecchymoses over the mastoid bone. Inspect for hemorrhage or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the nose or ears.

Also, test drainage with a sterile 4″ × 4″ gauze pad, and note whether you find a halo sign — a circle of clear fluid that surrounds the drainage, indicating CSF. Also, use a glucose reagent stick to test clear drainage for glucose. An abnormal test result indicates CSF, because mucus doesn’t contain glucose.

Medical Causes

Basilar skull fracture. A basilar skull fracture produces raccoon eyes after head trauma that doesn’t involve the orbital area. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the fracture site and may include pharyngeal hemorrhage, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, otorrhea, and a bulging tympanic membrane from blood or CSF. The patient may experience difficulty hearing, a headache, nausea, vomiting, cranial nerve palsies, and an altered LOC. He may also exhibit a positive Battle’s sign.

Other Causes

Surgery. Raccoon eyes occurring after craniotomy may indicate a meningeal tear and bleeding into the sinuses.

Special Considerations

Keep the patient on complete bed rest. Perform frequent neurologic evaluations to reevaluate his LOC. Also, check his vital signs hourly; be alert for such changes as bradypnea, bradycardia, hypertension, and a fever. To avoid worsening a dural tear, instruct the patient not to blow his nose, cough vigorously, or strain. If otorrhea or rhinorrhea is present, don’t attempt to stop the flow. Instead, place a sterile, loose gauze pad under the nose or ear to absorb drainage. Monitor the amount and test it with a glucose reagent strip to confirm or rule out CSF leakage.

Recognizing Raccoon Eyes

It’s usually easy to differentiate raccoon eyes from the “black eye” associated with facial trauma. Raccoon eyes (shown at right) are always bilateral. They develop 2 to 3 days after a closed head injury that results in a basilar skull fracture. In contrast, the periorbital ecchymosis that occurs with facial trauma can affect one eye or both. It usually develops within hours of injury.

To prevent further tearing of the mucous membranes and infection, never suction or pass a nasogastric tube through the patient’s nose. Observe the patient for signs and symptoms of meningitis, such as a fever and nuchal rigidity, and expect to administer a prophylactic antibiotic.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as skull X-ray and, possibly, a computed tomography scan. If the dural tear doesn’t heal spontaneously, contrast cisternography may be performed to locate the tear, possibly followed by corrective surgery.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms of neurologic deterioration the patient should report and which activity limitations he needs. Instruct the patient on how to care for a scalp wound.

Pediatric Pointers

Raccoon eyes in children are usually caused by a basilar skull fracture after a fall.

Reference

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Rebound Tenderness[Blumberg’s sign]

A reliable indicator of peritonitis, rebound tenderness is intense, elicited abdominal pain caused by rebound of palpated tissue. The tenderness may be localized, as in an abscess, or generalized, as in perforation of an intra-abdominal organ. Rebound tenderness usually occurs with abdominal pain, tenderness, and rigidity. When a patient has sudden, severe abdominal pain, this symptom is usually elicited to detect peritoneal inflammation.

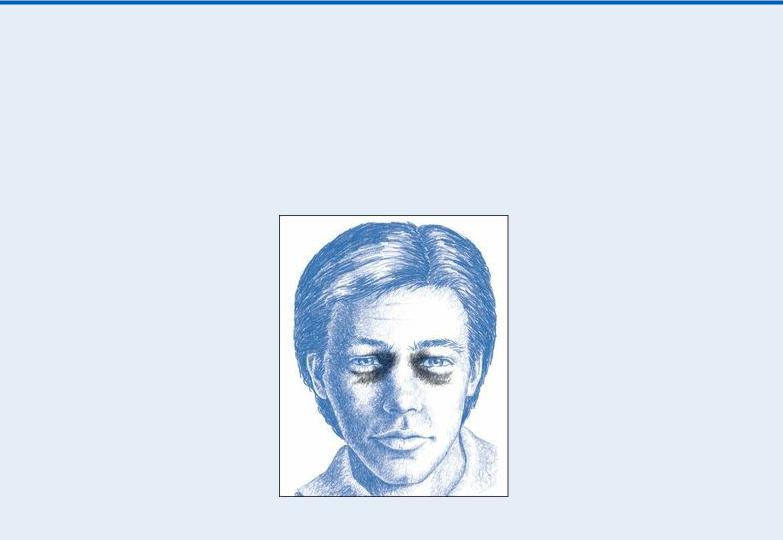

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting Rebound Tenderness

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting Rebound Tenderness

To elicit rebound tenderness, help the patient into a supine position with his knees flexed to relax the abdominal muscles. Push your fingers deeply and steadily into his abdomen (as shown). Then, quickly release the pressure. Pain that results from the rebound of palpated tissue

— rebound tenderness — indicates peritoneal inflammation or peritonitis.

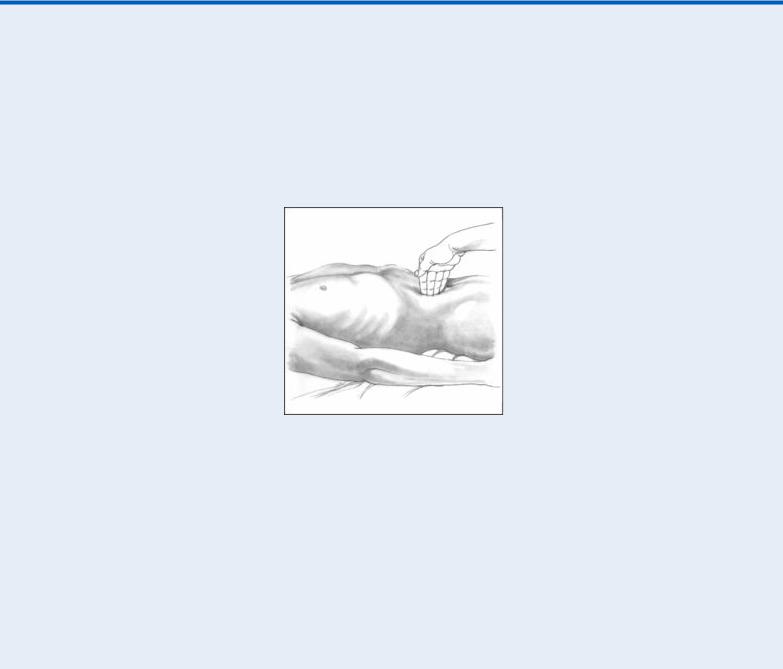

You can also elicit this symptom on a miniature scale by percussing the patient’s abdomen lightly and indirectly (as shown). Better still, simply ask the patient to cough. This allows you to elicit rebound tenderness without having to touch the patient’s abdomen and may also increase his cooperation because he won’t associate exacerbation of his pain with your actions.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

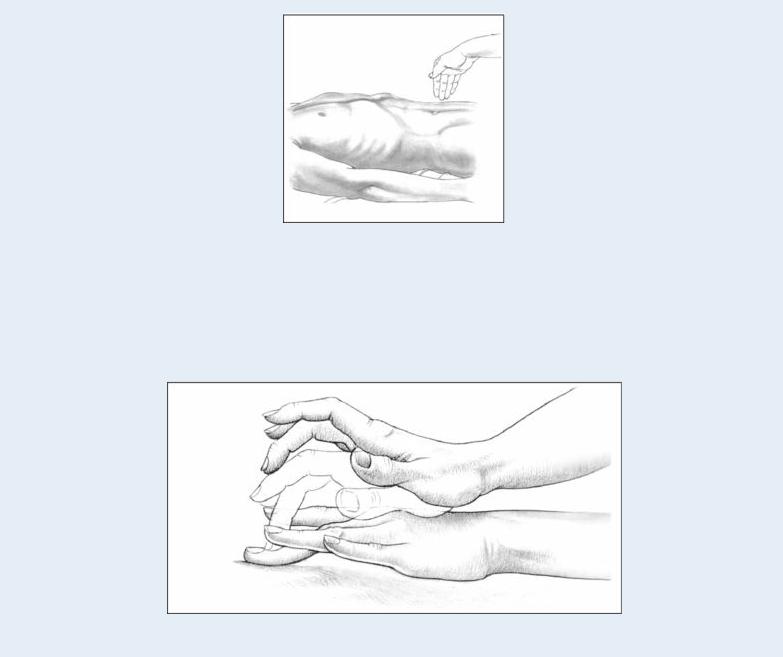

If you elicit rebound tenderness in a patient who’s experiencing constant, severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter, and begin administering I.V. fluids. Also, insert an indwelling urinary catheter, and monitor intake and output. Give supplemental oxygen as needed, and continue to monitor the patient for signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him to describe the events that led up to the tenderness. Does movement, exertion, or another activity relieve or aggravate the tenderness? Also, ask about other signs and symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, a fever, or abdominal bloating or distention. Inspect the abdomen for distention, visible peristaltic waves, and scars. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds and characterize their motility. Palpate for associated rigidity or guarding, and percuss the