Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

smooth, slightly elevated patches with well-defined erythematous margins and pale centers of various shapes and sizes. It’s produced by the local release of histamine or other vasoactive substances as part of a hypersensitivity reaction. (See Recognizing Common Skin Lesions, page 549.)

Acute urticaria evolves rapidly and usually has a detectable cause, commonly hypersensitivity to certain drugs, foods, insect bites, inhalants, or contactants, emotional stress, or environmental factors. Although individual lesions usually subside within 12 to 24 hours, new crops of lesions may erupt continuously, thus prolonging the attack.

Urticaria lasting longer than 6 weeks is classified as chronic. The lesions may recur for months or years, and the underlying cause is usually unknown. Occasionally, a diagnosis of psychogenic urticaria is made.

Angioedema, or giant urticaria, is characterized by the acute eruption of wheals involving the mucous membranes and, occasionally, the arms, legs, or genitals.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

In an acute case of urticaria, quickly evaluate respiratory status, and take vital signs. Ensure patent I.V. access if you note any respiratory difficulty or signs of impending anaphylactic shock. Also, as appropriate, give local epinephrine or apply ice to the affected site to decrease absorption through vasoconstriction. Clear and maintain the airway, give oxygen as needed, and institute cardiac monitoring. Have resuscitation equipment at hand, and be prepared to begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Intubation or a tracheostomy may be required.

History

If the patient isn’t in distress, obtain a complete history. Does he have any known allergies? Does the urticaria follow a seasonal pattern? Do certain foods or drugs seem to aggravate it? Is there a relationship to physical exertion? Is the patient routinely exposed to chemicals on the job or at home? Has the patient recently changed or used new skin products or detergents? Obtain a detailed drug history, including prescription and over-the-counter drugs. Note any history of chronic or parasitic infection, skin disease, or a GI disorder.

Medical Causes

Anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis — an acute reaction — is marked by the rapid eruption of diffuse urticaria and angioedema, with wheals ranging from pinpoint to palm size or larger. Lesions are usually pruritic and stinging; paresthesia commonly precedes their eruption. Other acute findings include profound anxiety, weakness, diaphoresis, sneezing, shortness of breath, profuse rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, dysphagia, and warm, moist skin.

Hereditary angioedema. With hereditary angioedema — an autosomal dominant disorder — cutaneous involvement is manifested by nonpitting, nonpruritic edema of an extremity or the face. Respiratory mucosal involvement can produce life-threatening acute laryngeal edema.

Lyme’s disease. Although not diagnostic of Lyme’s disease — a tick-borne disease — urticaria may result from the characteristic skin lesion (erythema chronicum migrans). Later effects include constant malaise and fatigue, intermittent headache, fever, chills, lymphadenopathy,

neurologic and cardiac abnormalities, and arthritis.

Other Causes

Drugs. Drugs that can produce urticaria include aspirin, codeine, dextrans, immune serums, insulin, morphine, penicillin, quinine, sulfonamides, and vaccines.

Radiographic contrast medium. Radiographic contrast medium, especially when administered I.V., commonly produces urticaria.

Special Considerations

To help relieve the patient’s discomfort, apply a bland skin emollient or one containing menthol and phenol. Expect to give an antihistamine, a systemic corticosteroid, or, if stress is a suspected contributing factor, a tranquilizer. Tepid baths and cool compresses may also enhance vasoconstriction and decrease pruritus.

Teach the patient to avoid the causative stimulus, if identified.

Patient Counseling

Emphasize the importance of wearing medical identification for allergies. Stress ways to prevent anaphylaxis; explain the risks of delayed symptoms and which signs and symptoms to report. Also, teach the patient the proper use of an anaphylaxis kit.

Pediatric Pointers

Pediatric forms of urticaria include acute papular urticaria (usually after insect bites) and urticaria pigmentosa (rare). Hereditary angioedema may be causative.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

V

Vaginal Bleeding, Postmenopausal

Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding — bleeding that occurs 6 or more months after menopause — is an important indicator of gynecologic cancer. But it can also result from infection, a local pelvic disorder, estrogenic stimulation, atrophy of the endometrium, and physiologic thinning and drying of the vaginal mucous membranes. Bleeding from the vagina may be indicative of bleeding from another gynecological location, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, or vagina. Bleeding usually occurs as slight, brown or red spotting developing either spontaneously or following coitus or douching, but it may also occur as oozing of fresh blood or as bright red hemorrhage. Many patients

— especially those with a history of heavy menstrual flow — minimize the importance of this bleeding, delaying diagnosis.

History and Physical Examination

Determine the patient’s age and her age at menopause. Ask when she first noticed the abnormal bleeding. Then, obtain a thorough obstetric and gynecologic history. When did she begin menstruating? Were her periods regular? If not, ask her to describe any menstrual irregularities. How old was she when she first had intercourse? How many sexual partners has she had? Has she had any children? Has she had fertility problems? If possible, obtain an obstetric and gynecologic history of the patient’s mother, and ask about a family history of gynecologic cancer. Determine if the patient has any associated symptoms and if she’s taking estrogen.

Observe the external genitalia, noting the character of any vaginal discharge and the appearance of the labia, vaginal rugae, and clitoris. Carefully palpate the patient’s breasts and lymph nodes for nodules or enlargement. The patient will require pelvic and rectal examinations.

Medical Causes

Atrophic vaginitis. When bloody staining occurs, it usually follows coitus or douching. Characteristic white, watery vaginal discharge may be accompanied by pruritus, dyspareunia, and a burning sensation in the vagina and labia. Sparse pubic hair, a pale vagina with decreased rugae and small hemorrhagic spots, clitoral atrophy, and shrinking of the labia minora may also occur.

Cervical cancer. Early invasive cervical cancer causes vaginal spotting or heavier bleeding, usually after coitus or douching but occasionally spontaneously. Related findings include persistent, pink-tinged, and foul-smelling vaginal discharge and postcoital pain. As the cancer spreads, back and sciatic pain, leg swelling, anorexia, weight loss, hematuria, dysuria, rectal bleeding, and weakness may occur.

Cervical or endometrial polyps. Cervical or endometrial polyps are small, pedunculated growths that may cause spotting (possibly as a mucopurulent, pink discharge) after coitus, douching, or straining to defecate. Many endometrial polyps are asymptomatic, however.

Endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. Bleeding occurs early, can be brownish and scant or bright red and profuse, and usually follows coitus or douching. Bleeding later becomes heavier and more frequent, leading to clotting and anemia. Bleeding may be accompanied by pelvic, rectal, lower back, and leg pain. The uterus may be enlarged.

Ovarian tumors (feminizing). Estrogen-producing ovarian tumors can stimulate endometrial shedding and cause heavy bleeding unassociated with coitus or douching. A palpable pelvic mass, increased cervical mucus, breast enlargement, and spider angiomas may be present.

Vaginal cancer. Characteristic spotting or bleeding may be preceded by a thin, watery vaginal discharge. Bleeding may be spontaneous but usually follows coitus or douching. A firm, ulcerated vaginal lesion may be present; dyspareunia, urinary frequency, bladder and pelvic pain, rectal bleeding, and vulvar lesions may develop later.

Other Causes

Drugs. Unopposed estrogen replacement therapy is a common cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding. This can usually be reduced by adding progesterone (in women who haven’t had a hysterectomy) and by adjusting the patient’s estrogen dosage.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as ultrasonography to outline a cervical or uterine tumor; endometrial biopsy, colposcopy, or dilatation and curettage with hysteroscopy to obtain tissue for histologic examination; testing for occult blood in the stool; and vaginal and cervical cultures to detect infection. Discontinue estrogen until a diagnosis is made.

Patient Counseling

Reassure the patient that postmenopausal bleeding may be benign, but careful assessment is still needed.

Geriatric Pointers

Some 80% of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding is benign. However, the American Cancer Society recommends that any postmenopausal vaginal bleeding be evaluated. Malignancy should be ruled out.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Vaginal Discharge

Common in women of childbearing age, physiologic vaginal discharge is mucoid, clear or white,

nonbloody, and odorless. Produced by the cervical mucosa and, to a lesser degree, by the vulvar glands, this discharge may occasionally be scant or profuse due to estrogenic stimulation and changes during the patient’s menstrual cycle. However, a marked increase in discharge or a change in discharge color, odor, or consistency can signal disease. The discharge may result from infection, sexually transmitted disease, reproductive tract disease, fistulas, and certain drugs. In addition, the prolonged presence of a foreign body, such as a tampon or diaphragm, in the patient’s vagina can cause irritation and an inflammatory exudate, as can frequent douching, feminine hygiene products, contraceptive products, bubble baths, and colored or perfumed toilet papers.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient to describe the onset, color, consistency, odor, and texture of her vaginal discharge. How does the discharge differ from her usual vaginal secretions? Is the onset related to her menstrual cycle? Also, ask about associated symptoms, such as dysuria and perineal pruritus and burning. Does she have spotting after coitus or douching? Ask about recent changes in her sexual habits and hygiene practices. Is she or could she be pregnant? Next, ask if she has had vaginal discharge before or has ever been treated for a vaginal infection. What treatment did she receive? Did she complete the course of medication? Ask about her current use of medications, especially antibiotics, oral estrogens, and hormonal contraceptives.

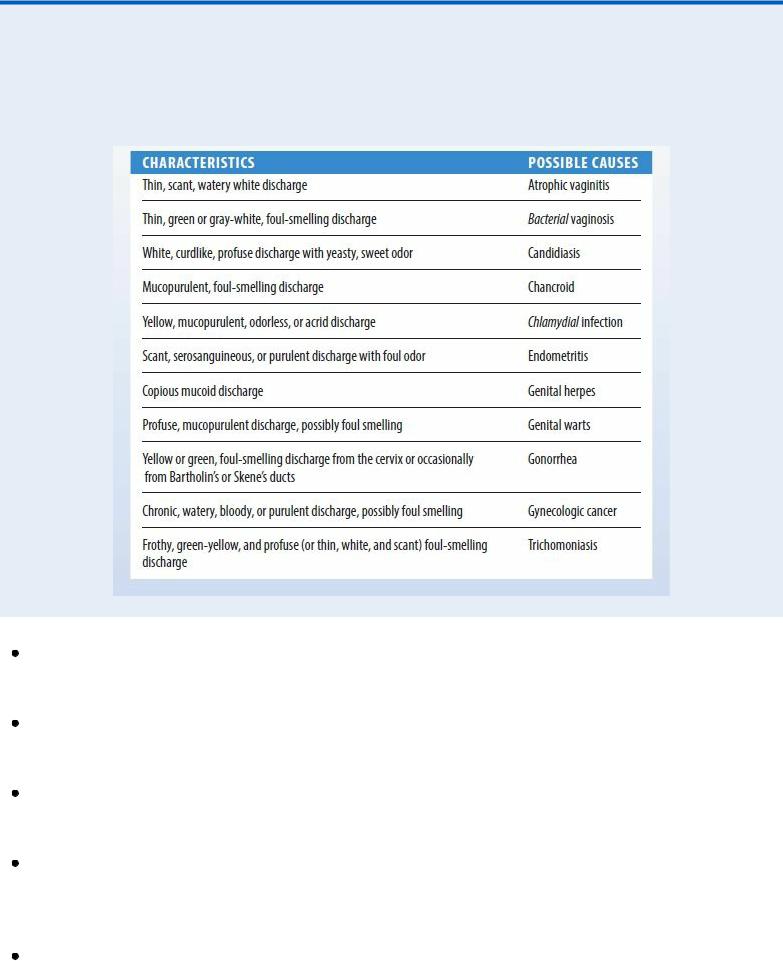

Examine the external genitalia, and note the character of the discharge. (See Identifying Causes of Vaginal Discharge.) Observe vulvar and vaginal tissues for redness, edema, and excoriation. Palpate the inguinal lymph nodes to detect tenderness or enlargement, and palpate the abdomen for tenderness. A pelvic examination may be required. Obtain vaginal discharge specimens for testing.

Medical Causes

Atrophic vaginitis. With atrophic vaginitis, a thin, scant, watery white vaginal discharge may be accompanied by pruritus, burning, tenderness, and bloody spotting after coitus or douching. Sparse pubic hair, a pale vagina with decreased rugae and small hemorrhagic spots, clitoral atrophy, and shrinking of the labia minora may also occur.

Bacterial vaginosis. Bacterial vaginosis (formerly called Gardnerella vaginalis and Haemophilus vaginalis) results from an ecologic disturbance of the vaginal flora. Causing a thin, foul-smelling, green or gray-white discharge, it adheres to the vaginal walls and can be easily wiped away, leaving healthy-looking tissue. Pruritus, redness, and other signs of vaginal irritation may occur but are usually minimal.

Candidiasis. Infection with Candida albicans causes a profuse, white, curdlike discharge with a yeasty, sweet odor. Onset is abrupt, usually just before menses or during a course of antibiotics. Exudate may be lightly attached to the labia and vaginal walls and is commonly accompanied by vulvar redness and edema. The inner thighs may be covered with a fine, red dermatitis and weeping erosions. Intense labial itching and burning may also occur. Some patients experience external dysuria.

Chancroid. Chancroid — a rare but highly contagious sexually transmitted disease — produces a mucopurulent, foul-smelling discharge and vulvar lesions that are initially erythematous and later ulcerated. Within 2 to 3 weeks, inguinal lymph nodes (usually unilateral) may become tender and enlarged, with pruritus, suppuration, and spontaneous drainage of nodes. Headache, malaise, and fever up to 102.2°F (39°C) are common.

Identifying Causes of Vaginal Discharge

The color, consistency, amount, and odor of your patient’s vaginal discharge provide important clues about the underlying disorder. For quick reference, use this chart to match common characteristics of vaginal discharge and their possible causes.

Chlamydial infection. Chlamydial infection causes a yellow, mucopurulent, odorless, or acrid vaginal discharge. Other findings include dysuria, dyspareunia, and vaginal bleeding after douching or coitus, especially following menses. Many women remain asymptomatic.

Endometritis. A scant, serosanguineous discharge with a foul odor can result from bacterial invasion of the endometrium. Associated findings include fever, lower back and abdominal pain, abdominal muscle spasm, malaise, dysmenorrhea, and an enlarged uterus.

Genital warts. Genital warts are mosaic, papular vulvar lesions that can cause a profuse, mucopurulent vaginal discharge, which may be foul smelling if the warts are infected. Patients frequently complain of burning or paresthesia in the vaginal introitus.

Gonorrhea. Although 80% of women with gonorrhea are asymptomatic, others have a yellow or green, foul-smelling discharge that can be expressed from Bartholin’s or Skene’s ducts. Other findings include dysuria, urinary frequency and incontinence, bleeding, and vaginal redness and swelling. Severe pelvic and lower abdominal pain and fever may develop.

Gynecologic cancer. Endometrial or cervical cancer produces a chronic, watery, bloody, or purulent vaginal discharge that may be foul smelling. Other findings include abnormal vaginal bleeding and, later, weight loss; pelvic, back, and leg pain; fatigue; urinary frequency; and

abdominal distention.

Herpes simplex (genital). A copious mucoid discharge can result from herpes simplex, but the initial complaint is painful, indurated vesicles and ulcerations on the labia, vagina, cervix, anus, thighs, or mouth. Erythema, marked edema, and tender inguinal lymph nodes may occur with fever, malaise, and dysuria.

Trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis can cause a foul-smelling discharge, which may be frothy, green-yellow, and profuse or thin, white, and scant. Other findings include pruritus; a red, inflamed vagina with tiny petechiae; dysuria and urinary frequency; and dyspareunia, postcoital spotting, menorrhagia, or dysmenorrhea. About 70% of patients are asymptomatic.

Other Causes

Contraceptive creams and jellies. Contraceptive creams and jellies can increase vaginal secretions.

Drugs. Drugs that contain estrogen, including hormonal contraceptives, can cause increased mucoid vaginal discharge. Antibiotics, such as tetracycline, may increase the risk of a candidal vaginal infection and discharge.

Radiation therapy. Irradiation of the reproductive tract can cause a watery, odorless vaginal discharge.

Special Considerations

Teach the patient to keep her perineum clean and dry. Also, tell her to avoid wearing tight-fitting clothing and nylon underwear and to instead wear cotton-crotched underwear and pantyhose. If appropriate, suggest that the patient douche with a solution of 5 T of white vinegar to 2 qt (2 L) of warm water to help relieve her discomfort.

If the patient has a vaginal infection, tell her to continue taking the prescribed medication even if her symptoms clear or she menstruates. Also, advise her to avoid intercourse until her symptoms clear and then to have her partner use condoms until she completes her course of medication. If her condition is sexually transmitted, instruct her on safe sex methods.

Patient Counseling

Emphasize the importance of keeping the perineum clean and dry and avoiding tight-fitting clothing. Suggest douching with vinegar and water to relieve discomfort, if appropriate, and stress compliance with the prescribed drug regimen. Instruct the patient to avoid intercourse until symptoms of infection clear, and provide information on safer sex practices.

Pediatric Pointers

Female neonates who have been exposed to maternal estrogens in utero may have a white mucous vaginal discharge for the first month after birth; a yellow mucous discharge indicates a pathologic condition. In the older child, a purulent, foul-smelling, and possibly bloody vaginal discharge commonly results from a foreign object placed in the vagina. The possibility of sexual abuse should also be considered.

Geriatric Pointers

The postmenopausal vaginal mucosa becomes thin due to decreased estrogen levels. Together with a rise in vaginal pH, this reduces resistance to infectious agents, increasing the incidence of vaginitis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Vertigo

Vertigo is an illusion of movement in which the patient feels that he’s revolving in space (subjective vertigo) or that his surroundings are revolving around him (objective vertigo). He may complain of feeling pulled sideways, as though drawn by a magnet.

A common symptom, vertigo usually begins abruptly and may be temporary or permanent and mild or severe. It may worsen when the patient moves and subside when he lies down. It’s often confused with dizziness — a sensation of imbalance and light-headedness that is nonspecific. However, unlike dizziness, vertigo is commonly accompanied by nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, and tinnitus or hearing loss. Although the patient’s limb coordination is unaffected, vertiginous gait may occur.

Vertigo may result from a neurologic or otologic disorder that affects the equilibratory apparatus (the vestibule, semicircular canals, eighth cranial nerve, vestibular nuclei in the brain stem and their temporal lobe connections, and eyes). However, this symptom may also result from alcohol intoxication, hyperventilation, and postural changes (benign postural vertigo). It may also be an adverse effect of certain drugs, tests, or procedures.

History and Physical Examination

Ask your patient to describe the onset and duration of his vertigo, being careful to distinguish this symptom from dizziness. Does he feel that he’s moving or that his surroundings are moving around him? How often do the attacks occur? Do they follow position changes, or are they unpredictable? Find out if the patient can walk during an attack, if he leans to one side, and if he’s ever fallen. Ask if he experiences motion sickness and if he prefers one position during an attack. Obtain a recent drug history, and note any evidence of alcohol abuse.

Perform a neurologic assessment, focusing particularly on eighth cranial nerve function. Observe the patient’s gait and posture for abnormalities.

Medical Causes

Acoustic neuroma. Acoustic neuroma is a tumor of the eighth cranial nerve that causes mild, intermittent vertigo and unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Other findings include tinnitus, postauricular or suboccipital pain, and — with cranial nerve compression — facial paralysis.

Benign positional vertigo. With benign positional vertigo, debris in a semicircular canal produces vertigo on head position change, which lasts a few minutes. It’s usually temporary and can be effectively treated with positional maneuvers.

Brain stem ischemia. Brain stem ischemia produces sudden, severe vertigo that may become episodic and later persistent. Associated findings include ataxia, nausea, vomiting, increased blood pressure, tachycardia, nystagmus, and lateral deviation of the eyes toward the side of the lesion. Hemiparesis and paresthesia may also occur.

Head trauma. Persistent vertigo, occurring soon after injury, accompanies spontaneous or positional nystagmus and, if the temporal bone is fractured, hearing loss. Associated findings include headache, nausea, vomiting, and decreased LOC. Behavioral changes, diplopia or visual blurring, seizures, motor or sensory deficits, and signs of increased intracranial pressure may also occur.

Herpes zoster. Infection of the eighth cranial nerve produces sudden onset of vertigo accompanied by facial paralysis, hearing loss in the affected ear, and herpetic vesicular lesions in the auditory canal.

Labyrinthitis. Severe vertigo begins abruptly with labyrinthitis, an inner ear infection. Vertigo may occur in a single episode or may recur over months or years. Associated findings include nausea, vomiting, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, and nystagmus.

Ménière’s disease. With Ménière’s disease, labyrinthine dysfunction causes abrupt onset of vertigo, lasting minutes, hours, or days. Unpredictable episodes of severe vertigo, hearing loss, and unsteady gait may cause the patient to fall. During an attack, any sudden motion of the head or eyes can precipitate nausea and vomiting.

Multiple sclerosis (MS). Episodic vertigo may occur early and become persistent. Other early findings include diplopia, visual blurring, and paresthesia. MS may also produce nystagmus, constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, and ataxia.

Seizures. Temporal lobe seizures may produce vertigo, usually associated with other symptoms of partial complex seizures.

Vestibular neuritis. With vestibular neuritis, severe vertigo usually begins abruptly and lasts several days, without tinnitus or hearing loss. Other findings include nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Caloric testing (irrigating the ears with warm or cold water) can induce vertigo.

Drugs and alcohol. High or toxic doses of certain drugs or alcohol may produce vertigo. These drugs include salicylates, aminoglycosides, antibiotics, quinine, and hormonal contraceptives. Surgery and other procedures. Ear surgery may cause vertigo that lasts for several days. Also, administration of overly warm or cold eardrops or irrigating solutions can cause vertigo.

Special Considerations

Place the patient in a comfortable position, and monitor his vital signs and LOC. Keep the side rails up if he’s in bed, or help him to a chair if he’s standing when vertigo occurs. Darken the room and keep him calm. Administer drugs to control nausea and vomiting and meclizine or dimenhydrinate to

decrease labyrinthine irritability.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as electronystagmography, EEG, and X-rays of the middle and inner ears.

Patient Counseling

Explain the need for moving around with assistance. Emphasize the need to avoid sudden position changes and performing dangerous tasks.

Pediatric Pointers

Ear infection is a common cause of vertigo in children. Vestibular neuritis may also cause this symptom.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Vesicular Rash

A vesicular rash is a scattered or linear distribution of blister-like lesions — sharply circumscribed and filled with clear, cloudy, or bloody fluid. The lesions, which are usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter, may occur singly or may occur in groups. (See Recognizing Common Skin Lesions, page 551.) They sometimes occur with bullae — fluid-filled lesions that are larger than 0.5 cm in diameter.

A vesicular rash may be mild or severe and temporary or permanent. It can result from infection, inflammation, or allergic reactions.

History and Physical Examination

Ask your patient when the rash began, how it spread, and whether it has appeared before. Did other skin lesions precede eruption of the vesicles? Obtain a thorough drug history. If the patient has used a topical medication, what type did he use and when was it last applied? Also, ask about associated signs and symptoms. Find out if he has a family history of skin disorders, and ask about allergies, recent infections, insect bites, and exposure to allergens.

Examine the patient’s skin, noting if it’s dry, oily, or moist. Observe the general distribution of the lesions, and record their exact location. Note the color, shape, and size of the lesions, and check for crusts, scales, scars, macules, papules, or wheals. Palpate the vesicles or bullae to determine if they’re flaccid or tense. Slide your finger across the skin to see if the outer layer of epidermis separates easily from the basal layer (Nikolsky’s sign).

Medical Causes

Burns (second degree). Thermal burns that affect the epidermis and part of the dermis cause vesicles and bullae, with erythema, swelling, pain, and moistness.