Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

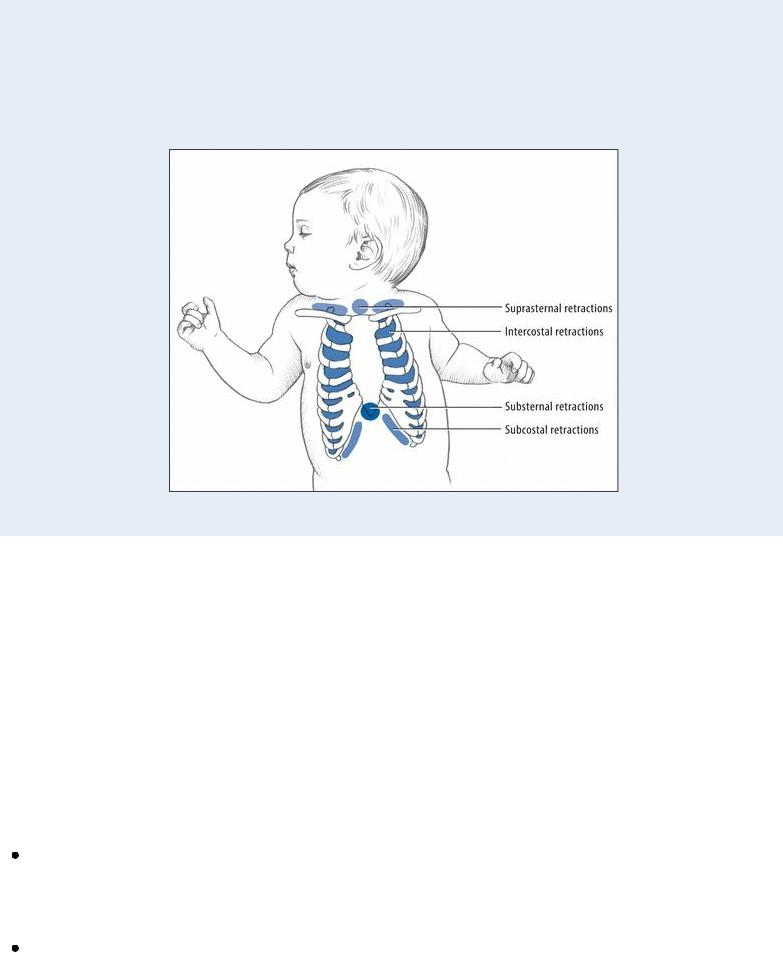

substernal retractions usually result from lower respiratory tract disorders; suprasternal retractions, from upper respiratory tract disorders.

Mild intercostal retractions alone may be normal. However, intercostal retractions accompanied by subcostal and substernal retractions may indicate moderate respiratory distress. Deep suprasternal retractions typically indicate severe distress.

History and Physical Examination

If the child’s condition permits, ask his parents about his medical history. Was he born prematurely? Was he born with a low birth weight? Was the delivery complicated? Ask about recent signs of an upper respiratory tract infection, such as a runny nose, a cough, and a low-grade fever. How often has the child had respiratory problems during the past year? Does he participate in a day care program or have school-aged siblings? Has he been in contact with anyone who has had a cold, the flu, or other respiratory ailments? Did he ever have respiratory syncytial virus? Did he aspirate food, liquid, or a foreign body? Inquire about a personal or family history of allergies or asthma.

Medical Causes

Asthma attack. Intercostal and suprasternal retractions may accompany an asthma attack. They’re preceded by dyspnea, wheezing, a hacking cough, and pallor. Related features include cyanosis or flushing, crackles, rhonchi, diaphoresis, tachycardia, tachypnea, a frightened, anxious expression, and, in patients with severe distress, nasal flaring.

Epiglottiditis. Epiglottiditis is a life-threatening bacterial infection that may precipitate severe respiratory distress with suprasternal, substernal, and intercostal retractions; stridor; nasal flaring; cyanosis; and tachycardia. Early features include a sudden onset of a barking cough and high fever, a sore throat, hoarseness, dysphagia, drooling, dyspnea, and restlessness. The child

becomes panicky as edema makes breathing difficult. Total airway occlusion may occur in 2 to 5 hours.

Heart failure. Usually linked to a congenital heart defect in children, heart failure may cause intercostal and substernal retractions along with nasal flaring, progressive tachypnea, and — in severe respiratory distress — grunting respirations, edema, and cyanosis. Other findings include a productive cough, crackles, jugular vein distention, tachycardia, right upper quadrant pain, anorexia, and fatigue.

Laryngotracheobronchitis (acute). With laryngotracheobronchitis, a viral infection, substernal and intercostal retractions typically follow a low to moderate fever, runny nose, poor appetite, a barking cough, hoarseness, and inspiratory stridor. Associated signs and symptoms include tachycardia; shallow, rapid respirations; restlessness; irritability; and pale, cyanotic skin.

Pneumonia (bacterial). Pneumonia begins with signs and symptoms of acute infection, such as a high fever and lethargy, which are followed by subcostal and intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, dyspnea, tachypnea, grunting respirations, cyanosis, and a productive cough. Auscultation may reveal diminished breath sounds, scattered crackles, and sibilant rhonchi over the affected lung. GI effects may include vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal distention.

Respiratory distress syndrome. Substernal and subcostal retractions are an early sign of respiratory distress syndrome, a life-threatening syndrome, which affects premature neonates shortly after birth. Associated early signs include tachypnea, tachycardia, and expiratory grunting. As respiratory distress worsens, intercostal and suprasternal retractions typically occur, and apnea or irregular respirations replace grunting. Other effects include nasal flaring, cyanosis, lethargy, and eventual unresponsiveness as well as bradycardia and hypotension. Auscultation may detect crackles over the lung bases on deep inspiration and harsh, diminished breath sounds. Oliguria and peripheral edema may occur.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the child’s vital signs. Keep suction equipment and an appropriate-sized airway at the bedside. If the infant weighs less than 15 lb (6.8 kg), place him in an oxygen hood. If he weighs more, place him in a cool mist tent instead. Perform chest physical therapy with postural drainage to help mobilize and drain excess lung secretions. A bronchodilator or, occasionally, a steroid may also be used.

Prepare the child for chest X-rays, cultures, pulmonary function tests, and arterial blood gas analysis. Explain the procedures to his parents, and have them calm and comfort the child.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient or his family about the proper use of prescribed drugs at home and the need to maintain a humidified environment. Stress the importance of ensuring adequate hydration.

Pediatric Pointers

When examining a child for retractions, know that crying may accentuate the contractions.

Geriatric Pointers

Although retractions may occur at any age, they’re more difficult to assess in an older patient who’s

obese or who has chronic chest wall stiffness or deformity.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Rhinorrhea

Common but rarely serious, rhinorrhea is the free discharge of thin nasal mucus. It can be self-limiting or chronic, resulting from a nasal, sinus, or systemic disorder or from a basilar skull fracture. Rhinorrhea can also result from sinus or cranial surgery, excessive use of vasoconstricting nose drops or sprays, or inhalation of an irritant, such as tobacco smoke, dust, and fumes. Depending on the cause, the discharge may be clear, purulent, bloody, or serosanguineous.

History and Physical Examination

Begin the history by asking the patient if the discharge runs from both nostrils. Is the discharge intermittent or persistent? Did it begin suddenly or gradually? Does the position of his head affect the discharge?

Next, ask the patient to characterize the discharge. Is it watery, bloody, purulent, or foul smelling? Is it copious or scanty? Does the discharge worsen or improve with the time of day? Also, find out if the patient is using medications, especially nose drops or nasal sprays. Has he been exposed to nasal irritants at home or at work? Does he experience seasonal allergies? Did he recently experience a head injury?

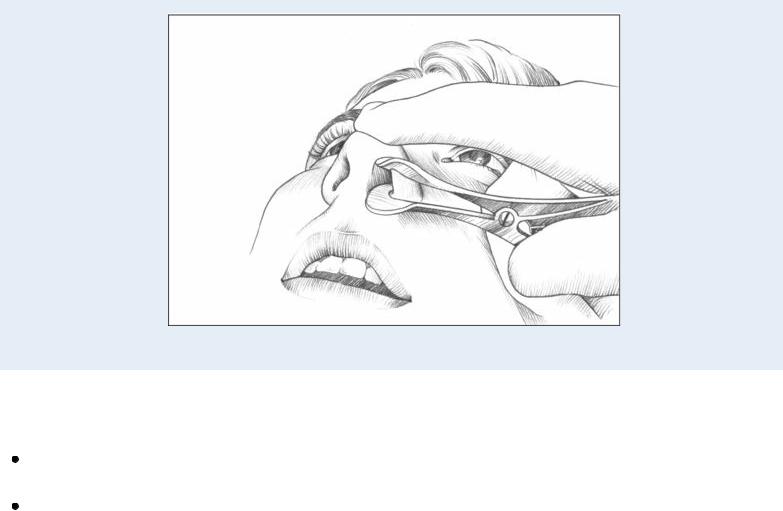

Examine the patient’s nose, checking airflow from each nostril. Evaluate the size, color, and condition of the turbinate mucosa (normally pale pink). Note if the mucosa is red, unusually pale, blue, or gray. Then, examine the area beneath each turbinate. (See Using a Nasal Speculum.) Make sure to palpate over the frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses for tenderness.

To differentiate nasal mucus from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), collect a small amount of drainage on a glucose test strip. If CSF (which contains glucose) is present, the test result will be abnormal. Finally, using a nonirritating substance, make sure to test for anosmia.

Medical Causes

Basilar skull fracture. A tear in the dura can lead to cerebrospinal rhinorrhea, which increases when the patient lowers his head. Other findings include epistaxis, otorrhea, and a bulging tympanum from blood or fluid. A basilar fracture may also cause a headache, facial paralysis, nausea and vomiting, impaired eye movement, ocular deviation, vision and hearing loss, a depressed level of consciousness, Battle’s sign, and raccoon eyes.

Common cold. An initially watery nasal discharge may become thicker and mucopurulent. Related findings include sneezing, nasal congestion, a dry and hacking cough, a sore throat, mouth breathing, and a transient loss of smell and taste. The patient may also experience

malaise, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, a slight headache, dry lips, and a red upper lip and nose. Nasal or sinus tumors. Nasal tumors can produce an intermittent, unilateral bloody or serosanguineous discharge that may be purulent and foul smelling. Nasal congestion, postnasal drip, and a headache may also occur. In advanced stages, paranasal sinus tumors may cause a cheek mass or eye displacement, facial paresthesia or pain, and nasal obstruction.

Rhinitis. Allergic rhinitis produces an episodic, profuse watery discharge. (A mucopurulent discharge indicates infection.) Typical associated signs and symptoms include increased lacrimation; nasal congestion; itchy eyes, nose, and throat; postnasal drip; recurrent sneezing; mouth breathing; an impaired sense of smell; and a frontal or temporal headache. Also, the turbinates are pale and engorged; the mucosa, pale and boggy.

With atrophic rhinitis, the nasal discharge is scanty, purulent, and foul smelling. Nasal obstruction is common, and the crusts may bleed on removal. The mucosa is pale pink and shiny. With vasomotor rhinitis, a profuse and watery nasal discharge accompanies chronic nasal obstruction, sneezing, recurrent postnasal drip, and pale, swollen turbinates. The nasal septum is pink; the mucosa, blue.

Sinusitis. With acute sinusitis, a thick and purulent nasal discharge leads to a purulent postnasal drip that results in throat pain and halitosis. The patient may also experience nasal congestion, severe pain and tenderness over the involved sinuses, fever, headache, and malaise.

With chronic sinusitis, the nasal discharge is usually scanty, thick, and intermittently purulent. Nasal congestion and low-grade discomfort or pressure over the involved sinuses can be persistent or recurrent. The patient may also be suffering from a chronic sore throat and nasal polyps.

With chronic fungal sinusitis, the clinical picture resembles that of chronic bacterial sinusitis. However, some cases — especially patients who are immunocompromised — may progress rapidly to exophthalmos, blindness, intracranial extension, and, eventually, death.

EXAMINATION TIP Using a Nasal Speculum

EXAMINATION TIP Using a Nasal Speculum

To visualize the interior of the nares, use a nasal speculum and a good light source such as a penlight. Hold the speculum in the palm of one hand and the penlight in the other hand. Have the patient tilt her head back slightly and rest it against a wall or other firm support, if possible. Insert the speculum blades about ½ (1.3 cm) into the nasal vestibule, as shown.

Place your index finger on the tip of the patient’s nose for stability. Carefully open the speculum blades. Shine the light source in the direction of the nares. Now, inspect the nares, as shown. The mucosa should be deep pink. Note any discharge, masses, lesions, or mucosal swellings. Check the nasal septum for perforation, bleeding, or crusting. Bluish turbinates suggest allergy. A rounded, elongated projection suggests a polyp.

Other Causes

Drugs. Nasal sprays or nose drops containing vasoconstrictors may cause rebound rhinorrhea (rhinitis medicamentosa) if used longer than 5 days.

Surgery. Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea may occur after sinus or cranial surgery.

Special Considerations

You may have to prepare the patient for X-rays of the sinuses or skull (if you suspect a skull fracture) and a computed tomography scan. You may also need to administer an antihistamine, a decongestant, an analgesic, or an antipyretic. Advise the patient to drink plenty of fluids to thin secretions.

Pregnancy causes physiologic changes that may aggravate rhinorrhea, resulting in eosinophilia and chronic irritable airways.

Patient Counseling

Explain the proper use of nasal over-the-counter sprays.

Pediatric Pointers

Be aware that rhinorrhea in children may stem from choanal atresia, allergic or chronic rhinitis, acute ethmoiditis, or congenital syphilis. Assume that unilateral rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction is caused by a foreign body in the nose until proven otherwise.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients may suffer increased adverse reactions to drugs used to treat rhinorrhea, such as elevated blood pressure or confusion.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Rhonchi

Rhonchi are continuous adventitious breath sounds detected by auscultation. They’re usually louder and lower pitched than crackles — more like a hoarse moan or a deep snore — though they may be described as rattling, sonorous, bubbling, rumbling, or musical. However, sibilant rhonchi, or wheezes, are high pitched.

Rhonchi are heard over large airways such as the trachea. They can occur in a patient with a pulmonary disorder when air flows through passages that have been narrowed by secretions, a tumor or foreign body, bronchospasm, or mucosal thickening. The resulting vibration of airway walls produces the rhonchi.

History and Physical Examination

If you auscultate rhonchi, take the patient’s vital signs, including oxygen saturation, and be alert for signs of respiratory distress. Characterize the patient’s respirations as rapid or slow, shallow or deep, and regular or irregular. Inspect the chest, noting accessory muscle use. Is the patient audibly wheezing or gurgling? Auscultate for other abnormal breath sounds, such as crackles and a pleural friction rub. If you detect these sounds, note their location. Are breath sounds diminished or absent? Next, percuss the chest. If the patient has a cough, note its frequency and characterize its sound. If it’s productive, examine the sputum for color, odor, consistency, and blood.

Ask related questions: Does the patient smoke? If so, obtain a history in pack-years. Has he recently lost weight or felt tired or weak? Does he have asthma or another pulmonary disorder? Is he taking any prescribed or over-the-counter medication?

During the examination, keep in mind that thick or excessive secretions, bronchospasm, or inflammation of mucous membranes may lead to airway obstruction. If necessary, suction the patient and keep equipment available for inserting an artificial airway. Keep a bronchodilator available to treat bronchospasm.

Medical Causes

Asthma. An asthma attack can cause rhonchi, crackles, and, commonly, wheezing. Other features include apprehension, a dry cough that later becomes productive, prolonged expirations, and intercostal and supraclavicular retractions on inspiration. The patient may also exhibit increased accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, tachypnea, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and flushing or cyanosis.

Bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis causes lower-lobe rhonchi and crackles, which coughing may help relieve. Its classic sign is a cough that produces mucopurulent, foul-smelling, and, possibly,

bloody sputum. Other findings include a fever, weight loss, exertional dyspnea, fatigue, malaise, halitosis, weakness, and late-stage clubbing.

Bronchitis. Acute tracheobronchitis produces sonorous rhonchi and wheezing due to bronchospasm or increased mucus in the airways. Related findings include chills, a sore throat, a low-grade fever (rising up to 102°F [38.9°C] in those with severe illness), muscle and back pain, and substernal tightness. A cough becomes productive as secretions increase.

With chronic bronchitis, auscultation may reveal scattered rhonchi, coarse crackles, wheezing, high-pitched piping sounds, and prolonged expirations. An early hacking cough later becomes productive. The patient also displays exertional dyspnea, increased accessory muscle use, barrel chest, cyanosis, tachypnea, and clubbing (a late sign).

Pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonias can cause rhonchi and a dry cough that later becomes productive. Related signs and symptoms — shaking chills, a high fever, myalgia, a headache, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia, dyspnea, cyanosis, diaphoresis, decreased breath sounds, and fine crackles — develop suddenly.

Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis causes rhonchi and wheezing. Other features include a cough with a fever, occasional chills, pleuritic chest pain, a sore throat, a headache, a backache, malaise, marked weakness, anorexia, hemoptysis, and an itchy macular rash.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Pulmonary function tests or bronchoscopy can loosen secretions and mucus, causing rhonchi.

Respiratory therapy. Respiratory therapy may produce rhonchi from loosened secretions and mucus.

Special Considerations

To ease the patient’s breathing, place him in semi-Fowler’s position, and reposition him every 2 hours. Administer an antibiotic, a bronchodilator, and an expectorant. Also, provide humidification to thin secretions, relieve inflammation, and prevent drying. Pulmonary physiotherapy with postural drainage and percussion can also help loosen secretions. Use tracheal suctioning, if necessary, to help the patient clear secretions and to promote oxygenation and comfort. Promote coughing and deep breathing and incentive spirometry.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as arterial blood gas analysis, pulmonary function studies, sputum analysis, and chest X-rays.

Patient Counseling

Explain deep breathing and coughing techniques and the need for increasing fluid intake. Discuss how increasing activity levels can help loosen secretions and improve oxygenation.

Pediatric Pointers

Rhonchi in children can result from bacterial pneumonia, cystic fibrosis, and croup syndrome. Because a respiratory tract disorder may begin abruptly and progress rapidly in an infant or a

child, observe closely for signs of airway obstruction.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

S

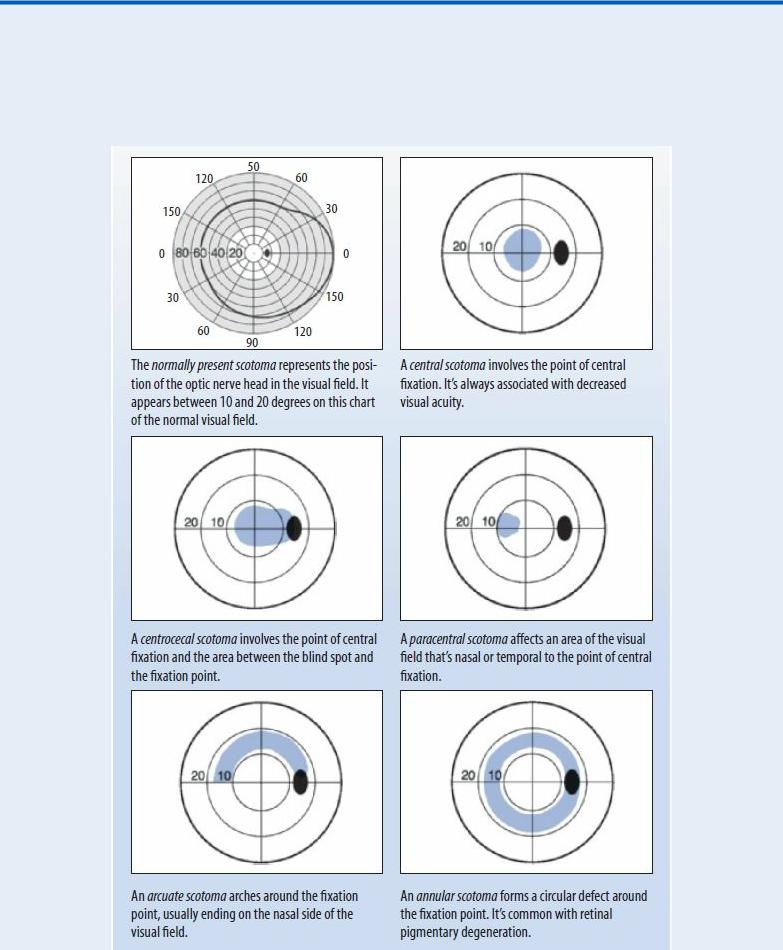

Scotoma

A scotoma is an area of partial or complete blindness within an otherwise normal or slightly impaired visual field. Usually located within the central 30-degree area, the defect ranges from absolute blindness to a barely detectable loss of visual acuity. Typically, the patient can pinpoint the scotoma’s location in the visual field. (See Locating Scotomas, page 646.)

A scotoma can result from a retinal, choroidal, or optic nerve disorder. It can be classified as absolute, relative, or scintillating. An absolute scotoma refers to the total inability to see all sizes of test objects used in mapping the visual field. A relative scotoma, in contrast, refers to the ability to see only large test objects. A scintillating scotoma refers to the flashes or bursts of light commonly seen during a migraine headache.

History and Physical Examination

First, identify and characterize the scotoma, using such visual field tests as the tangent screen examination, the Goldmann perimeter test, or the automated perimetry test. Two other visual field tests — confrontation testing and the Amsler grid — may also help in identifying a scotoma.

Next, test the patient’s visual acuity, and inspect his pupils for size, equality, and reaction to light. An ophthalmoscopic examination and measurement of intraocular pressure are necessary.

Explore the patient’s medical history, noting especially eye disorders, vision problems, or chronic systemic disorders. Find out if he takes medications or uses eye drops.

Medical Causes

Chorioretinitis. Inflammation of the choroid and retina can produce a scotoma. Ophthalmoscopic examination reveals clouding and cells in the vitreous, subretinal hemorrhage, and neovascularization. The patient may have photophobia along with blurred vision.

Macular degeneration. Any degenerative process or disorder affecting the fovea centralis results in a central scotoma. Ophthalmoscopic examination reveals changes in the macular area. The patient may notice subtle changes in visual acuity, in color perception, and in the size and shape of objects.

Optic neuritis. Inflammation, degeneration, or demyelination of the optic nerve produces a central, circular, or centrocecal scotoma. The scotoma may be unilateral with involvement of one nerve or bilateral with involvement of both nerves. It can vary in size, density, and symmetry. The patient may report severe vision loss or blurring, lasting up to 3 weeks, and pain

— especially with eye movement. Common ophthalmoscopic findings include hyperemia of the optic disk, retinal vein distention, blurred disk margins, and filling of the physiologic cup. Retinal pigmentary degeneration. Retinal pigmentary degeneration causes premature retinal cell changes leading to cell death. One disorder, retinitis pigmentosa, initially involves loss of peripheral rods; the resulting annular scotoma progresses concentrically until only a central field

of vision (tunnel vision) remains. The earliest symptom — impaired night vision — appears during adolescence. Associated signs include narrowing of the retinal blood vessels and pallor of the optic disk. Eventually, with invasion of the macula, blindness may occur.

Locating Scotomas

Scotomas, or “blind spots,” are classified according to the affected area of the visual field. The normal physiologic scotoma — shown in the temporal region of the right eye — appears in black in all the illustrations.