Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Biliary cirrhosis. Clay-colored stools typically follow unexplained pruritus that worsens at bedtime, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain; these features may be present for years. Associated findings include jaundice, hyperpigmentation, and signs of malabsorption, such as nocturnal diarrhea, steatorrhea, purpura, and bone and back pain due to osteomalacia. The patient may also develop firm, nontender hepatomegaly; hematemesis; ascites; edema; and xanthomas on his palms, soles, and elbows.

Cholangitis (sclerosing). Characterized by fibrosis of the bile ducts, cholangitis, a chronic inflammatory disorder, may cause clay-colored stools, chronic or intermittent jaundice, pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, chills, and a fever.

Cholelithiasis. Stones in the biliary tract may cause clay-colored stools when they obstruct the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis). However, if the obstruction is intermittent, the stools may alternate between normal and clay colored. Associated symptoms include dyspepsia and — in sudden, severe obstruction — characteristic biliary colic. This right upper quadrant pain intensifies over several hours, may radiate to the epigastrium or shoulder blades, and is unrelieved by antacids. The pain is accompanied by tachycardia, restlessness, nausea, intolerance to certain foods, vomiting, upper abdominal tenderness, a fever, chills, and jaundice. Hepatic cancer. Before clay-colored stools develop, the patient usually experiences weight loss, weakness, and anorexia. Later, he may develop nodular, firm hepatomegaly, jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, ascites, dependent edema, and a fever. A bruit, hum, or rubbing sound may be heard on auscultation if the cancer involves a large part of the liver.

Hepatitis. With viral hepatitis, clay-colored stools signal the start of the icteric phase and are typi-cally followed by jaundice within 1 to 5 days. Associated signs include mild weight loss and dark urine as well as continuation of some preicteric findings, such as anorexia and tender hepatomegaly. During the icteric phase, the patient may become irritable and develop right upper quadrant pain, splenomegaly, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and severe pruritus. After jaundice disappears, the patient continues to experience fatigue, flatulence, abdominal pain or tenderness, and dyspepsia, although his appetite usually returns and hepatomegaly subsides. The posticteric phase generally lasts from 2 to 6 weeks, with full recovery in 6 months.

With cholestatic nonviral hepatitis, clay-colored stools occur with other signs of viral hepatitis. Pancreatic cancer. Common bile duct obstruction associated with pancreatic cancer may cause clay-colored stools. Classic associated features include abdominal or back pain, jaundice, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, weakness, and a fever. Other possible effects include diarrhea, skin lesions (especially on the legs), emotional lability, splenomegaly, and signs of GI bleeding. Auscultation may reveal a bruit in the periumbilical area and left upper quadrant.

Pancreatitis (acute). Pancreatitis is an inflammatory disorder that may cause clay-colored stools, dark urine, and jaundice. Typically, it also causes severe epigastric pain that radiates to the back and is aggravated by lying down. Associated findings include nausea and vomiting, a fever, abdominal rigidity and tenderness, hypoactive bowel sounds, and crackles at the lung bases. With severe pancreatitis, findings include marked restlessness, tachycardia, mottled skin, and cold, sweaty extremities.

Other Causes

Biliary surgery. Biliary surgery may cause bile duct stricture, resulting in clay-colored stools.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as liver enzyme and serum bilirubin levels, hepatitis panels, sonograms, a computed tomography scan, endoscopy, retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and stool analysis.

Patient Counseling

Explain dietary modifications, the importance of avoiding alcohol, the need for rest, and ways to reduce abdominal pain.

Pediatric Pointers

Clay-colored stools may occur in infants with biliary atresia.

Geriatric Pointers

Because elderly patients with cholelithiasis have a greater risk of developing complications if the condition isn’t treated, surgery should be considered early on for treatment of persistent systems.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Stridor

A loud, harsh, musical respiratory sound, stridor results from an obstruction in the trachea or larynx. Usually heard during inspiration, this sign may also occur during expiration in severe upper airway obstruction. It may begin as low-pitched “croaking” and progress to high-pitched “crowing” as respirations become more vigorous.

Life-threatening upper airway obstruction can stem from foreign-body aspiration, increased secretions, an intraluminal tumor, localized edema or muscle spasms, and external compression by a tumor or aneurysm.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you hear stridor, quickly check the patient’s vital signs, including oxygen saturation, and examine him for other signs of partial airway obstruction — choking or gagging, tachypnea, dyspnea, shallow respirations, intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, tachycardia, cyanosis, and diaphoresis. (Be aware that abrupt cessation of stridor signals complete obstruction in which the patient has inspiratory chest movement but absent breath sounds. Unable to talk,

he quickly becomes lethargic and loses consciousness.)

If you detect signs of airway obstruction, try to clear the airway with back blows or abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver). Next, administer oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask, or prepare the patient for emergency endotracheal (ET) intubation or tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation. (See Emergency Endotracheal Intubation, page 678.) Have equipment ready to suction aspirated vomitus or blood through the ET or tracheostomy tube. Connect the patient to a cardiac monitor, and position him upright to ease his breathing.

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a patient history from him or a family member. First, find out when the stridor began. Has he had it before? Does he have an upper respiratory tract infection? If so, how long has he had it?

Ask about a history of allergies, tumors, and respiratory and vascular disorders. Note recent exposure to smoke or noxious fumes or gases. Next, explore associated signs and symptoms. Does stridor occur with pain or a cough?

Then, examine the patient’s mouth for excessive secretions, foreign matter, inflammation, and swelling. Assess his neck for swelling, masses, subcutaneous crepitation, and scars. Observe the patient’s chest for delayed, decreased, or asymmetrical chest expansion. Auscultate for wheezes, rhonchi, crackles, rubs, and other abnormal breath sounds. Percuss for dullness, tympany, or flatness. Finally, note burns or signs of trauma, such as ecchymoses and lacerations.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Emergency Endotracheal Intubation

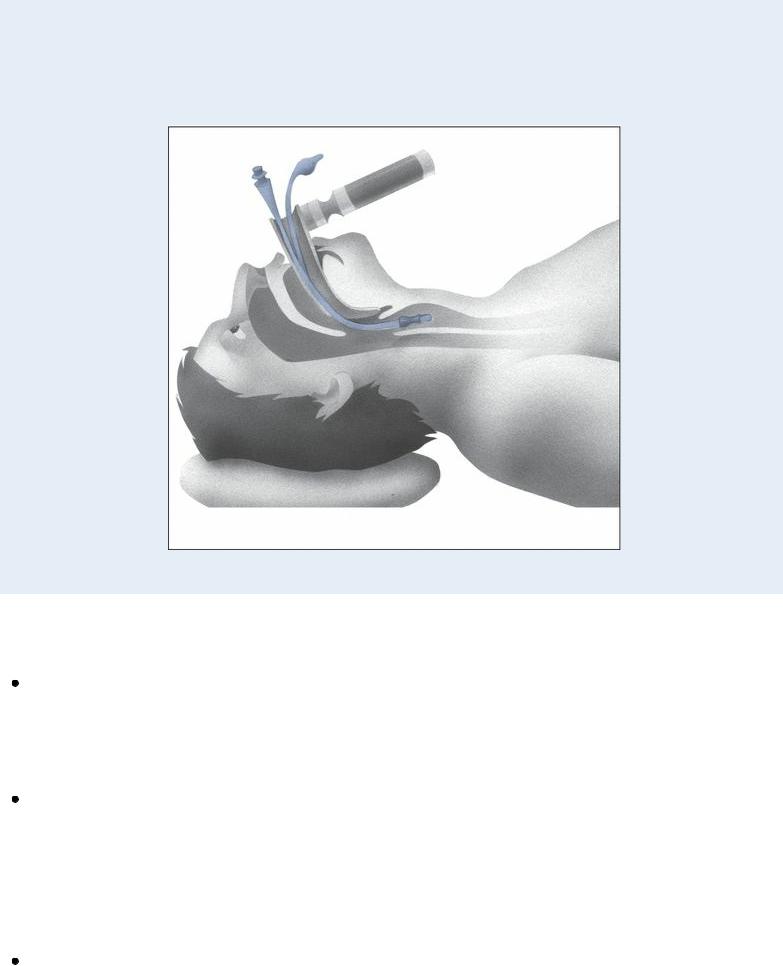

For a patient with stridor, you may have to perform emergency endotracheal (ET) intubation to establish a patent airway and administer mechanical ventilation. Just follow these essential steps:

Gather the necessary equipment. Explain the procedure to the patient.

Place the patient flat on his back with a small blanket or pillow under his head. This position aligns the axis of the oropharynx, posterior pharynx, and trachea.

Check the cuff on the ET tube for leaks.

After intubation, inflate the cuff, using the minimal leak technique.

Check tube placement by auscultating for bilateral breath sounds or using a capnometer; observe the patient for chest expansion, and feel for warm exhalations at the ET tube’s opening.

Insert an oral airway or bite block.

Secure the tube and airway with an ET tube holder or tape.

Suction secretions from the patient’s mouth and the ET tube as needed. Administer oxygen or initiate mechanical ventilation (or both).

After the patient has been intubated, suction secretions as needed and check cuff pressure once every shift (correcting any air leaks with the minimal leak technique). Provide mouth care every 2 to 3 hours and as needed. Prepare the patient for chest X-rays to check tube placement, and restrain and reassure him as needed.

Medical Causes

Airway trauma. Local trauma to the upper airway commonly causes acute obstruction, resulting in the sudden onset of stridor. Accompanying this sign are dysphonia, dysphagia, hemoptysis, cyanosis, accessory muscle use, intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, tachypnea, progressive dyspnea, and shallow respirations. Palpation may reveal subcutaneous crepitation in the neck or upper chest.

Anaphylaxis. With a severe allergic reaction, upper airway edema and laryngospasm cause stridor and other signs and symptoms of respiratory distress: nasal flaring, wheezing, accessory muscle use, intercostal retractions, and dyspnea. The patient may also develop nasal congestion and profuse, watery rhinorrhea. Typically, these respiratory effects are preceded by a feeling of impending doom or fear, weakness, diaphoresis, sneezing, nasal pruritus, urticaria, erythema, and angioedema. Common associated findings include chest or throat tightness, dysphagia, and, possibly, signs of shock, such as hypotension, tachycardia, and cool, clammy skin.

Anthrax (inhalation). Initial signs and symptoms are flulike and include a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain. The disease generally occurs in two stages with a period of recovery after the initial symptoms. The second stage develops abruptly with rapid deterioration marked by stridor, a fever, dyspnea, and hypotension generally leading to death within 24 hours.

Radiologic findings include mediastinitis and symmetric mediastinal widening.

Aspiration of a foreign body. Sudden stridor is characteristic in foreign-body aspiration, a lifethreatening situation. Related findings include an abrupt onset of dry, paroxysmal coughing; gagging or choking; hoarseness; tachycardia; wheezing; dyspnea; tachypnea; intercostal muscle retractions; diminished breath sounds; cyanosis; and shallow respirations. The patient typically appears anxious and distressed.

Hypocalcemia. With hypocalcemia, laryngospasm can cause stridor. Other findings include paresthesia, carpopedal spasm, and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs.

Inhalation injury. Within 48 hours after inhalation of smoke or noxious fumes, the patient may develop laryngeal edema and bronchospasms, resulting in stridor. Associated signs and symptoms include singed nasal hairs, orofacial burns, coughing, hoarseness, sooty sputum, crackles, rhonchi, wheezes, and other signs and symptoms of respiratory distress, such as dyspnea, accessory muscle use, intercostal retractions, and nasal flaring.

Mediastinal tumor. Commonly producing no symptoms at first, a mediastinal tumor may eventually compress the trachea and bronchi, resulting in stridor. Its other effects include hoarseness, a brassy cough, a tracheal shift or tug, dilated neck veins, swelling of the face and neck, stertorous respirations, and suprasternal retractions on inspiration. The patient may also report dyspnea, dysphagia, and pain in the chest, shoulder, or arm.

Retrosternal thyroid. Retrosternal thyroid is an anatomic abnormality that causes stridor, dysphagia, a cough, hoarseness, and tracheal deviation. It can also cause signs of thyrotoxicosis.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Bronchoscopy or laryngoscopy may precipitate laryngospasm and stridor. Treatments. After prolonged intubation, the patient may exhibit laryngeal edema and stridor when the tube is removed. Aerosol therapy with epinephrine may reduce stridor. Reintubation may be necessary in some cases. Neck surgery, such as thyroidectomy, may cause laryngeal paralysis and stridor.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs closely. Prepare him for diagnostic tests, such as arterial blood gas analysis and chest X-rays.

Patient Counseling

Teach about the underlying condition and explain all procedures and treatments.

Pediatric Pointers

Stridor is a major sign of airway obstruction in a child. When you hear this sign, you must intervene quickly to prevent total airway obstruction. This emergency can happen more rapidly in a child because his airway is narrower than an adult’s.

Causes of stridor in children include foreign-body aspiration, croup syndrome, laryngeal diphtheria, pertussis, retropharyngeal abscess, and congenital abnormalities of the larynx.

Therapy for partial airway obstruction typically involves hot or cold steam in a mist tent or hood,

parenteral fluids and electrolytes, and plenty of rest.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Syncope

A common neurologic sign, syncope (or fainting) refers to a transient loss of consciousness associated with impaired cerebral blood supply or cerebral hypoxia. It usually occurs abruptly and lasts for seconds to minutes. An episode of syncope usually starts as a feeling of light-headedness. A patient can usually prevent an episode of syncope by lying down or sitting with his head between his knees. Typically, the patient lies motionless with his skeletal muscles relaxed but sphincter muscles controlled. However, the depth of unconsciousness varies — some patients can hear voices or see blurred outlines; others are unaware of their surroundings.

In many ways, syncope simulates death: The patient is strikingly pale with a slow, weak pulse, hypotension, and almost imperceptible breathing. If severe hypotension lasts for 20 seconds or longer, the patient may also develop convulsive, tonic-clonic movements.

Syncope may result from cardiac and cerebrovascular disorders, hypoxemia, and postural changes in the presence of autonomic dysfunction. It may also follow vigorous coughing (tussive syncope) and emotional stress, injury, shock, or pain (vasovagal syncope, or common fainting). Hysterical syncope may also follow emotional stress but isn’t accompanied by other vasodepressor effects.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you see a patient faint, ensure a patent airway and the patient’s safety, and take his vital signs. Then, place the patient in a supine position, elevate his legs, and loosen tight clothing. Be alert for tachycardia, bradycardia, or an irregular pulse. Meanwhile, place him on a cardiac monitor to detect arrhythmias. If an arrhythmia appears, give oxygen and insert an I.V. line for medications or fluids. Be ready to begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cardioversion, defibrillation, or insertion of a temporary pacemaker may be required.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports a fainting episode, gather information about the episode from him and his family. Did he feel weak, light-headed, nauseous, or sweaty just before he fainted? Did he get up quickly from a chair or from lying down? During the fainting episode, did he have muscle spasms or incontinence? How long was he unconscious? When he regained consciousness, was he alert or confused? Did he have a headache? Has he fainted before? If so, how often does it occur?

Next, take the patient’s vital signs and examine him for any injuries that may have occurred during his fall.

Medical Causes

Aortic arch syndrome. With aortic arch syndrome, the patient experiences syncope and may exhibit weak or abruptly absent carotid pulses and unequal or absent radial pulses. Early signs and symptoms include night sweats, pallor, nausea, anorexia, weight loss, arthralgia, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. He may also develop hypotension in the arms; neck, shoulder, and chest pain; paresthesia; intermittent claudication; bruits; vision disturbances; and dizziness.

Aortic stenosis. A cardinal late sign, syncope is accompanied by exertional dyspnea and angina. Related findings include marked fatigue, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, palpitations, and diminished carotid pulses. Typically, auscultation reveals atrial and ventricular gallops as well as a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo systolic ejection murmur that’s loudest at the right sternal border of the second intercostal space.

Cardiac arrhythmias. Any arrhythmia that decreases cardiac output and impairs cerebral circulation may cause syncope. Other effects — such as palpitations, pallor, confusion, diaphoresis, dyspnea, and hypotension — usually develop first. However, with Adams-Stokes syndrome, syncope may occur without warning. During syncope, the patient develops asystole, which may precipitate spasm and myoclonic jerks if prolonged. He also displays an ashen pallor that progresses to cyanosis, incontinence, a bilateral Babinski’s reflex, and fixed pupils.

Hypoxemia. Regardless of its cause, severe hypoxemia may produce syncope. Common related effects include confusion, tachycardia, restlessness, and incoordination.

Orthostatic hypotension. Syncope occurs when the patient rises quickly from a recumbent position. Look for a drop of 10 to 20 mm Hg or more in systolic or diastolic blood pressure as well as tachycardia, pallor, dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, and diaphoresis.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Marked by transient neurologic deficits, TIAs may produce syncope and a decreased level of consciousness. Other findings vary with the affected artery, but may include vision loss, nystagmus, aphasia, dysarthria, unilateral numbness, hemiparesis or hemiplegia, tinnitus, facial weakness, dysphagia, and a staggering or an uncoordinated gait.

Other Causes

Drugs. Quinidine may cause syncope — and possibly sudden death — associated with ventricular fibrillation. Prazosin may cause severe orthostatic hypotension and syncope, usually after the first dose. Occasionally, griseofulvin, levodopa, and indomethacin can produce syncope.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs closely. Prepare him for an electrocardiogram and Holter monitor, carotid duplex, carotid Doppler, and electrophysiology studies.

Patient Counseling

Discuss with the patient the underlying condition, and encourage him to pace his activities. Explain

that he should avoid standing for prolonged periods and what measures to take if he feels faint.

Pediatric Pointers

Syncope is much less common in children than in adults. It may result from a cardiac or neurologic disorder, allergies, or emotional stress.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

T

Tachycardia

Easily detected by counting the apical, carotid, or radial pulse, tachycardia is a heart rate greater than 100 beats/minute. The patient with tachycardia usually complains of palpitations or of a “racing” heart. This common sign normally occurs in response to emotional or physical stress, such as excitement, exercise, pain, anxiety, and fever. It may also result from the use of stimulants, such as caffeine and tobacco. However, tachycardia may be an early sign of a life-threatening disorder, such as cardiogenic, hypovolemic, or septic shock. It may also result from a cardiovascular, respiratory, or metabolic disorder or from the effects of certain drugs, tests, or treatments. (See What Happens in Tachycardia, page 684.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After detecting tachycardia, take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). If the patient has increased or decreased blood pressure and is drowsy or confused, administer oxygen and begin cardiac monitoring. Perform electrocardiography (ECG) to examine for reduced cardiac output, which may initiate or result from tachycardia. Insert an I.V. line for fluid, blood product, and drug administration, and gather emergency resuscitation equipment.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, take a focused history. Find out if he has had palpitations. If so, how were they treated? Explore associated symptoms. Is the patient dizzy or short of breath? Is he weak or fatigued? Is he experiencing episodes of syncope or chest pain? Next, ask about a history of trauma, diabetes, or cardiac, pulmonary, or thyroid disorders. Also, obtain an alcohol and drug history, including prescription, over-the-counter, and illicit drugs.

Inspect the patient’s skin for pallor or cyanosis. Assess pulses, noting peripheral edema. Finally, auscultate the heart and lungs for abnormal sounds or rhythms.

Medical Causes

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Besides tachycardia, ARDS causes crackles, rhonchi, dyspnea, tachypnea, nasal flaring, and grunting respirations. Other findings include cyanosis, anxiety, decreased LOC, and abnormal chest X-ray findings.

Adrenocortical insufficiency. With adrenocortical insufficiency, tachycardia commonly occurs with a weak pulse as well as progressive weakness and fatigue, which may become so severe that the patient requires bed rest. Other signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, altered bowel habits, weight loss, orthostatic hypotension, irritability, bronze skin,

decreased libido, and syncope. Some patients report an enhanced sense of taste, smell, and hearing.

What Happens in Tachycardia

Tachycardia represents the heart’s effort to deliver more oxygen to body tissues by increasing the rate at which blood passes through the vessels. This sign can reflect overstimulation within the sinoatrial node, the atrium, the atrioventricular node, or the ventricles.

Because heart rate affects cardiac output (cardiac output = heart rate × stroke volume), tachycardia can lower cardiac output by reducing ventricular filling time and stroke volume (the output of each ventricle at every contraction). As cardiac output plummets, arterial pressure and peripheral perfusion decrease. Tachycardia further aggravates myocardial ischemia by increasing the heart’s demand for oxygen while reducing the duration of diastole — the period of greatest coronary flow.

Anaphylactic shock. With life-threatening anaphylactic shock, tachycardia and hypotension develop within minutes after exposure to an allergen, such as penicillin or an insect sting. Typically, the patient is visibly anxious and has severe pruritus, perhaps with urticaria and a pounding headache. Other findings may include flushed and clammy skin, a cough, dyspnea, nausea, abdominal cramps, seizures, stridor, change or loss of voice associated with laryngeal edema, and urinary urgency and incontinence.

Anemia. Tachycardia and bounding pulse are characteristic with anemia. Associated signs and symptoms include fatigue, pallor, dyspnea, and, possibly, bleeding tendencies. Auscultation may reveal an atrial gallop, a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries, and crackles.

Aortic insufficiency. Accompanying tachycardia with aortic insufficiency are a “waterhammer” bounding pulse and a large, diffuse apical heave. With severe insufficiency, widened pulse pressure occurs. Auscultation reveals a hallmark diastolic murmur that starts with the second heart sound; is decrescendo, high-pitched, and blowing; and is heard best at the left sternal border of the second and third intercostal spaces. An atrial or ventricular gallop, an early systolic murmur, an Austin Flint murmur (apical diastolic rumble), or Duroziez’s sign (a murmur over the femoral artery during systole and diastole) may also be heard. Other findings include angina, dyspnea, palpitations, strong and abrupt carotid pulsations, pallor, and signs of heart failure, such as crackles and jugular vein distention.

Aortic stenosis. Typically, aortic stenosis — a valvular disorder — causes tachycardia, a weak, thready pulse, and an atrial gallop. Its chief features, however, are exertional dyspnea, angina, dizziness, and syncope. Aortic stenosis also causes a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo systolic ejection murmur that’s loudest at the right sternal border of the second intercostal space. Other findings include palpitations, crackles, and fatigue.

Cardiac arrhythmias. Tachycardia may occur with an irregular heart rhythm. The patient may be hypotensive and report dizziness, palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. Depending on his heart rate, he may also exhibit tachypnea, decreased LOC, and pale, cool, clammy skin.

Cardiac contusion. The result of blunt chest trauma, cardiac contusion may cause tachycardia, substernal pain, dyspnea, and palpitations. Assessment may detect sternal ecchymoses and a