Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Cryptosporidiosis. Weight loss may occur with cryptosporidiosis, an opportunistic protozoan infection. Other findings include profuse watery diarrhea, abdominal cramping, flatulence, anorexia, malaise, fever, nausea, vomiting, and myalgia.

Depression. Weight loss or weight gain may occur with severe depression, along with insomnia or hypersomnia, anorexia, apathy, fatigue, and feelings of worthlessness. Indecisiveness, incoherence, and suicidal thoughts or behavior may also occur.

Diabetes mellitus. Weight loss may occur with diabetes mellitus, despite increased appetite. Other findings include polydipsia, weakness, fatigue, and polyuria with nocturia.

Esophagitis. Painful inflammation of the esophagus leads to temporary avoidance of eating and subsequent weight loss. Intense pain in the mouth and anterior chest occurs, along with hypersalivation, dysphagia, tachypnea, and hematemesis. If a stricture develops, dysphagia and weight loss will recur.

Gastroenteritis. Malabsorption and dehydration cause weight loss in gastroenteritis. The loss may be sudden in acute viral infections or reactions or gradual in parasitic infection. Other findings include poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, hypotension, diarrhea, abdominal pain and tenderness, hyperactive bowel sounds, nausea, vomiting, fever, and malaise. Leukemia. Acute leukemia causes progressive weight loss accompanied by severe prostration; high fever; swollen, bleeding gums; and bleeding tendencies. Dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, and abdominal or bone pain may occur. As the disease progresses, neurologic symptoms may eventually develop.

Chronic leukemia, which occurs insidiously in adults, causes progressive weight loss with malaise, fatigue, pallor, enlarged spleen, bleeding tendencies, anemia, skin eruptions, anorexia, and fever.

Lymphoma. Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cause gradual weight loss. Associated findings include fever, fatigue, night sweats, malaise, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Scaly rashes and pruritus may develop.

Pulmonary tuberculosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis causes gradual weight loss, along with fatigue, weakness, anorexia, night sweats, and low-grade fever. Other clinical effects include a cough with bloody or mucopurulent sputum, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Examination may reveal dullness on percussion, crackles after coughing, increased tactile fremitus, and amphoric breath sounds.

Stomatitis. Inflammation of the oral mucosa (usually red, swollen, and ulcerated) in stomatitis causes weight loss due to decreased eating. Associated findings include fever, increased salivation, malaise, mouth pain, anorexia, and swollen, bleeding gums.

Thyrotoxicosis. With thyrotoxicosis, increased metabolism causes weight loss. Other characteristic signs and symptoms include nervousness, heat intolerance, diarrhea, increased appetite, palpitations, tachycardia, diaphoresis, fine tremor, and possibly an enlarged thyroid and exophthalmos. A ventricular or atrial gallop may be heard.

Other Causes

Drugs. Amphetamines and inappropriate dosage of thyroid preparations commonly lead to weight loss. Laxative abuse may cause a malabsorptive state that leads to weight loss. Chemotherapeutic agents cause stomatitis or nausea and vomiting, which, when severe, causes

weight loss.

Special Considerations

Refer your patient for psychological counseling if weight loss negatively affects his body image. If the patient has a chronic disease, administer hyperalimentation or tube feedings to maintain nutrition and to prevent edema, poor healing, and muscle wasting. Take daily calorie counts, and weigh him weekly. Consult a nutritionist to determine an appropriate diet and nutritional supplements with adequate calories.

Patient Counseling

Provide guidance in proper diet and keeping a food diary. Instruct the patient in good oral hygiene. Provide a referral to psychological counseling, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

In infants, weight loss may be caused by failure-to-thrive syndrome. In children, severe weight loss may be the first indication of diabetes mellitus. Chronic, gradual weight loss occurs in children with marasmus — nonedematous protein-calorie malnutrition.

Weight loss may also occur as a result of child abuse or neglect; an infection causing high fevers; hand-foot-and-mouth disease, which causes painful oral sores; a GI disorder causing vomiting and diarrhea; or celiac disease.

Geriatric Pointers

Some elderly patients experience mild, gradual weight loss due to changes in body composition, such as loss of height and lean body mass, and lower basal metabolic rate, leading to decreased energy requirements. Rapid, unintentional weight loss, however, is highly predictive of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. Other nondisease causes of weight loss in this group include tooth loss, difficulty chewing, and social isolation. Alcoholism may also cause weight loss.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wheezing[Sibilant Rhonchi]

Wheezes are adventitious breath sounds with a high-pitched, musical, squealing, creaking, or groaning quality. They are caused by air flowing at a high velocity through a narrowed airway. When they originate in the large airways, they can be heard by placing an unaided ear over the chest wall or at the mouth. When they originate in smaller airways, they can be heard by placing a stethoscope over the anterior or posterior chest. Unlike crackles and rhonchi, wheezes can’t be cleared by coughing.

Usually, prolonged wheezing occurs during expiration when bronchi are shortened and narrowed. Causes of airway narrowing include bronchospasm; mucosal thickening or edema; partial obstruction from a tumor, a foreign body, or secretions; and extrinsic pressure, as in tension pneumothorax or goiter. With airway obstruction, wheezing occurs during inspiration.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Examine the degree of the patient's respiratory distress. Is he responsive? Is he restless, confused, anxious, or afraid? Are his respirations abnormally fast, slow, shallow, or deep? Are they irregular? Can you hear wheezing through his mouth? Does he exhibit increased use of accessory muscles; increased chest wall motion; intercostal, suprasternal, or supraclavicular retractions; stridor; or nasal flaring? Take his other vital signs, noting hypotension or hypertension and decreased oxygen saturation or an irregular, weak, rapid, or slow pulse.

Help the patient relax, administer humidified oxygen by face mask, and encourage him to take slow, deep breaths. Have endotracheal intubation and emergency resuscitation equipment readily available. Call the respiratory therapy department to supply intermittent positive pressure breathing and nebulization treatments with bronchodilators. Insert an I.V. line for administration of drugs, such as diuretics, steroids, bronchodilators, and sedatives. Perform the abdominal thrust maneuver, as indicated, for airway obstruction.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in respiratory distress, obtain a history. What provokes his wheezing? Does he have asthma or allergies? Does he smoke or have a history of a pulmonary, cardiac, or circulatory disorder? Does he have cancer? Ask about recent surgery, illness, or trauma or changes in appetite, weight, exercise tolerance, or sleep patterns. Obtain a drug history. Ask about exposure to toxic fumes or any respiratory irritants. If he has a cough, ask how it sounds, when it starts, and how often it occurs. Does he have paroxysms of coughing? Is his cough dry, sputum producing, or bloody?

Ask the patient about chest pain. If he reports pain, determine its quality, onset, duration, intensity, and radiation. Does it increase with breathing, coughing, or certain positions?

Examine the patient’s nose and mouth for congestion, drainage, or signs of infection, such as halitosis. If he produces sputum, obtain a sample for examination. Check for cyanosis, pallor, clamminess, masses, tenderness, swelling, distended jugular veins, and enlarged lymph nodes. Inspect his chest for abnormal configuration and asymmetrical motion, and determine if the trachea is midline. (See Detecting Slight Tracheal Deviation, page 703.) Percuss for dullness or hyperresonance, and auscultate for crackles, rhonchi, or pleural friction rubs. Note absent or hypoactive breath sounds, abnormal heart sounds, gallops, or murmurs. Also, note arrhythmias, bradycardia, or tachycardia. (See Evaluating Breath Sounds, page 764.)

Medical Causes

Anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is an allergic reaction that can cause tracheal edema or bronchospasm, resulting in severe wheezing and stridor. Initial signs and symptoms include fright, weakness, sneezing, dyspnea, nasal pruritus, urticaria, erythema, and angioedema.

Respiratory distress occurs with nasal flaring, accessory muscle use, and intercostal retractions. Other findings include nasal edema and congestion; profuse, watery rhinorrhea; chest or throat tightness; and dysphagia. Cardiac effects include arrhythmias and hypotension.

Aspiration of a foreign body. Partial obstruction by a foreign body produces sudden onset of wheezing and possibly stridor; a dry, paroxysmal cough; gagging; and hoarseness. Other findings include tachycardia, dyspnea, decreased breath sounds and, possibly, cyanosis. A retained foreign body may cause inflammation leading to fever, pain, and swelling.

Aspiration pneumonitis. With aspiration pneumonitis, wheezing may accompany tachypnea, marked dyspnea, cyanosis, tachycardia, fever, productive (eventually purulent) cough, and pink, frothy sputum.

Asthma. Wheezing is an initial and cardinal sign of asthma. It’s heard at the mouth during expiration. An initially dry cough later becomes productive with thick mucus. Other findings include apprehension, prolonged expiration, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions, rhonchi, accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, and tachypnea. Asthma also produces tachycardia, diaphoresis, and flushing or cyanosis.

Blast lung injury. An acute onset of wheezing is a common sign of respiratory distress in blast lung injury. Associated respiratory findings include dyspnea, hemoptysis, cough, tachypnea, hypoxia, apnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and hemodynamic instability. Treatment is based on the nature of the explosion, the environment in which it occurred, and any chemical or biological agents involved.

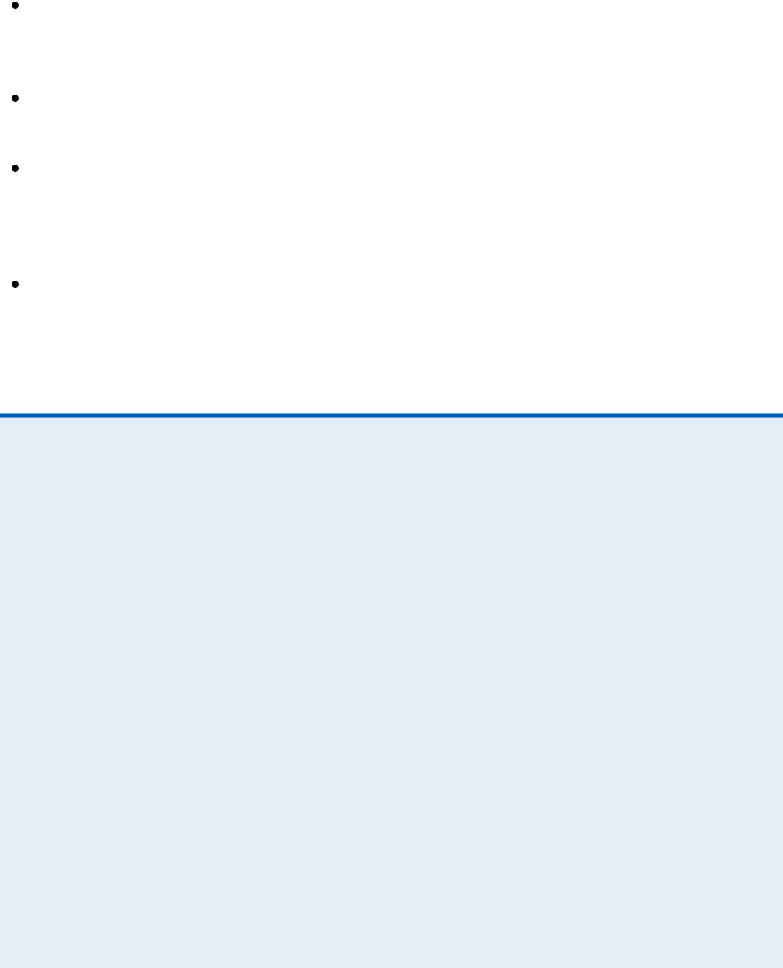

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Breath Sounds

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Breath Sounds

Diminished or absent breath sounds indicate some interference with airflow. If pus, fluid, or air fills the pleural space, breath sounds will be quieter than normal. If a foreign body or secretions obstruct a bronchus, breath sounds will be diminished or absent over distal lung tissue. Increased thickness of the chest wall, such as with a patient who is obese or extremely muscular, may cause breath sounds to be decreased, distant, or inaudible. Absent breath sounds typically indicate loss of ventilation power.

When air passes through narrowed airways or through moisture, or when the membranes lining the chest cavity become inflamed, adventitious breath sounds will be heard. These include crackles, rhonchi, wheezes, and pleural friction rubs. Usually, these sounds indicate pulmonary disease.

Follow the auscultation sequences shown to assess the patient's breath sounds. Have the patient take full, deep breaths, and compare sound variations from one side to the other. Note the location, timing, and character of any abnormal breath sounds.

Bronchial adenoma. Bronchial adenoma, an insidious disorder, produces unilateral, possibly severe wheezing. Common features are chronic cough and recurring hemoptysis. Symptoms of airway obstruction may occur later.

Bronchiectasis. Excessive mucus commonly causes intermittent and localized or diffuse wheezing. A copious, foul-smelling, mucopurulent cough is classic. It’s accompanied by hemoptysis, rhonchi, and coarse crackles. Weight loss, fatigue, weakness, exertional dyspnea, fever, malaise, halitosis, and late-stage clubbing may also occur.

Bronchitis (chronic). Bronchitis causes wheezing that varies in severity, location, and intensity. Associated findings include prolonged expiration, coarse crackles, scattered rhonchi, and a hacking cough that later becomes productive. Other effects include dyspnea, accessory muscle use, barrel chest, tachypnea, clubbing, edema, weight gain, and cyanosis.

Bronchogenic carcinoma. Obstruction may cause localized wheezing. Typical findings include a productive cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis (initially blood-tinged sputum, possibly leading to massive hemorrhage), anorexia, and weight loss. Upper extremity edema and chest pain may also occur.

Emphysema. Mild to moderate wheezing may occur with emphysema, a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Related findings include dyspnea, malaise, tachypnea, diminished breath sounds, peripheral cyanosis, pursed-lip breathing, anorexia, and malaise. Accessory muscle use, barrel chest, a chronic productive cough, and clubbing may also occur.

Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis may cause wheezing and rhonchi along with cough, fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain, headache, weakness, malaise, anorexia, and macular rash.

Pulmonary edema. Wheezing may occur with pulmonary edema, a life-threatening disorder. Other signs and symptoms include coughing, exertional and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and, later, orthopnea. Examination reveals tachycardia, tachypnea, dependent crackles, and a diastolic gallop. Severe pulmonary edema produces rapid, labored respirations; diffuse crackles; a productive cough with frothy, bloody sputum; arrhythmias; cold, clammy, cyanotic skin; hypotension; and thready pulse.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Wheezing typically occurs with RSV bronchiolitis, an

infection of the lower respiratory tract commonly seen in children under age 1 year. Other acute respiratory symptoms include apnea, coughing, rapid breathing, nasal flaring, fever, and chest retractions. Most children recover from RSV infection within 8 to 15 days without sequelae. Premature infants and those with underlying respiratory, cardiac, neuromuscular, and immunological conditions require special consideration.

Tracheobronchitis. Auscultation may detect wheezing, rhonchi, and crackles. The patient also has a cough, slight fever, sudden chills, muscle and back pain, and substernal tightness. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Wegener’s granulomatosis may cause mild to moderate wheezing if it compresses major airways. Other findings include a cough (possibly bloody), dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hemorrhagic skin lesions, and progressive renal failure. Epistaxis and severe sinusitis are common.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as chest X-rays, arterial blood gas analysis, pulmonary function tests, and sputum culture.

Ease the patient’s breathing by placing him in a semi-Fowler’s position and repositioning him frequently. Perform pulmonary physiotherapy as necessary.

Administer an antibiotic to treat infection, a bronchodilator to relieve bronchospasm and maintain patent airways, a steroid to reduce inflammation, and a mucolytic or expectorant to increase the flow of secretions. Provide humidification to thin secretions.

Patient Counseling

Provide the patient information about his prescribed drugs, and explain how to promote drainage and prevent pooling of secretions, if needed. Also, explain deep breathing and coughing techniques and the importance of increasing fluid intake.

Pediatric Pointers

Children are especially susceptible to wheezing because their small airways allow rapid obstruction. Primary causes of wheezing include bronchospasm, mucosal edema, and accumulation of secretions. These may occur with such disorders as cystic fibrosis, aspiration of a foreign body, acute bronchiolitis, and pulmonary hemosiderosis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

LESS COMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

POTENTIAL AGENTS OF BIOTERRORISM

COMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH HERBS

OBTAINING A HEALTH HISTORY

SELECTED REFERENCES

INDEX

LESS COMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

This appendix supplements the main text of Handbook of Signs & Symptoms, Fifth Edition, which provides detailed coverage of more than 250 signs and symptoms that are familiar, diagnostically significant, or indicative of an emergency. This section, in contrast, provides the definition and common causes of about 250 less-familiar, accessory, or nonspecific signs and symptoms. For an elicited sign, such as Chaddock’s sign, it also includes the technique for evoking the patient’s response.

The section also covers selected pediatric signs, such as low-set ears and Allis’ sign; psychiatric symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations; and nail and tongue signs, such as nail plate hypertrophy and tongue discoloration.

A

Aaron’s sign Pain in the chest or abdominal (precordial or epigastric) area that’s elicited by applying gentle but steadily increasing pressure over McBurney’s point. A positive sign indicates appendicitis.

Abadie’s sign Spasm of the levator muscle of the upper eyelid. This sign may be slight or pronounced and may affect one eye or both eyes. It reflects an exophthalmic goiter in Graves’ disease.

adipsia Abnormal absence of thirst. This symptom commonly occurs in hypothalamic injury or tumor, head injury, bronchial tumor, and cirrhosis.

agnosia Inability to recognize and interpret sensory stimuli, even though the principal sensation of the stimulus is known. Auditory agnosia refers to the inability to recognize familiar sounds. Astereognosis, or tactile agnosia, is the inability to recognize objects by touch or feel. Anosmia is the inability to recognize familiar smells; gustatory agnosia, the inability to recognize familiar tastes . Visual agnosia refers to the inability to recognize familiar objects by sight. Autotopagnosia is the inability to recognize body parts. Anosognosia refers to the denial or lack of awareness of a disease or defect (especially paralysis).Agnosias stem from lesions that affect the association areas of the parietal sensory cortex. They’re a common sequela of stroke.

agraphia Inability to express thoughts in writing. Aphasic agraphia is associated with spelling and grammatical errors, whereas constructional agraphia refers to the reversal or incorrect ordering of correctly spelled words. Apraxic agraphia refers to the inability to form letters in the absence of significant motor impairment.Agraphia commonly results from a stroke.

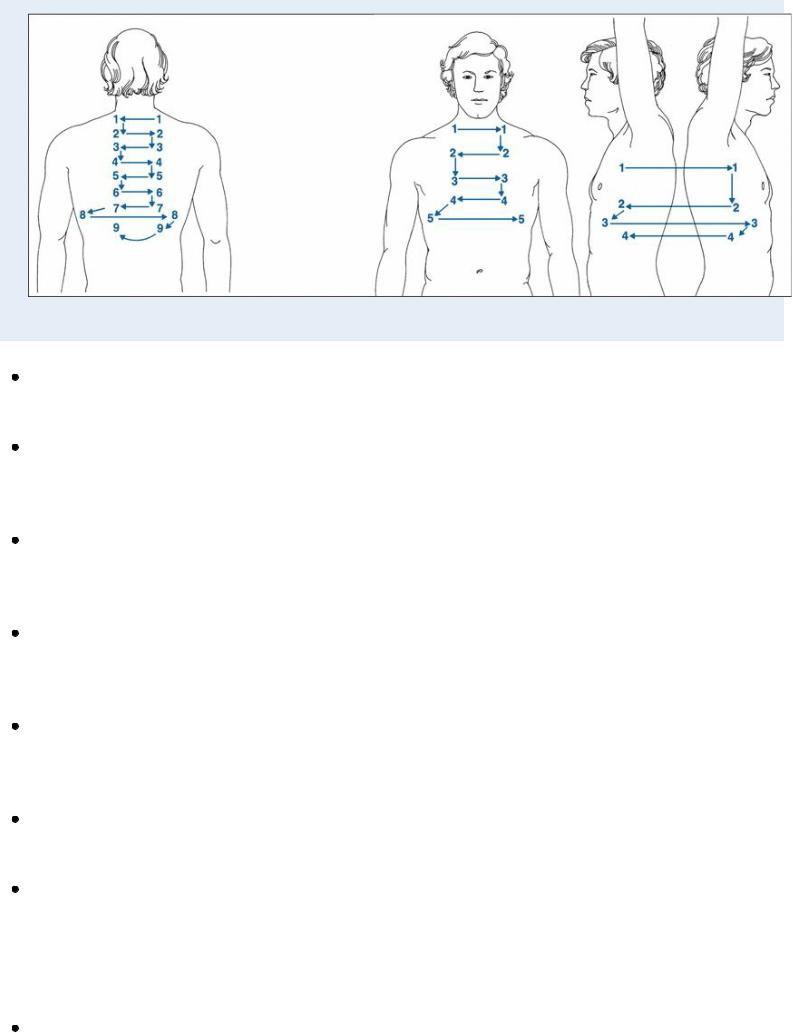

Allis’ sign In an adult: relaxation of the fascia lata between the iliac crest and greater trochanter due to fracture of the neck of the femur. To detect this sign, place a finger over the area between the iliac crest and greater trochanter and press firmly. If your finger sinks deeply into this area, you’ve detected Allis’ sign.In an infant: unequal leg lengths due to hip dislocation. To detect this sign, place the infant on the back with the pelvis flat. Then flex both legs at the knee and hip with the feet even. Next, compare the height of the knees. If they differ, suspect hip dislocation in the shorter leg.

ALLIS’ SIGN

ambivalence Simultaneous existence of conflicting feelings about a person, idea, or object (such as both love and hate). It causes uncertainty or indecisiveness about which course to follow. Severe, debilitating ambivalence can occur in schizophrenia.

Amoss’ sign A sparing maneuver to avoid pain upon flexion of the spine. To detect this sign, ask the patient to rise from a supine to a sitting position. The sign is observed when the patient places both hands on the examination table behind the back for support.

anesthesia Absence of cutaneous sensation of touch, temperature, and pain. This sensory loss may be partial or total, unilateral or bilateral. To detect anesthesia, ask the patient to close the eyes. Then touch the patient and ask him or her to specify the location. If the patient’s verbal skills

are immature or poor, watch for movement or changes in facial expression in response to your touch.

anisocoria A difference of 0.5 to 2 mm in pupil size. Anisocoria occurs normally in about 2% of people, in whom the pupillary inequality remains constant over time and despite changes in light. However, if anisocoria results from fixed dilation or constriction of one pupil or from slowed or impaired constriction of one pupil in response to light, it may indicate neurologic disease. Determining whether the abnormal pupil is dilated or constricted aids diagnosis.

apathy Absence or suppression of emotion or interest in the external environment and personal affairs. This indifference can result from many disorders, chiefly neurologic, psychological, respiratory, and renal — as well as from alcohol and drug use and abuse. It’s associated with many chronic disorders that cause personality changes and depression. In fact, apathy may be an early indicator of a severe disorder, such as a brain tumor or schizophrenia.

aphonia Inability to produce speech sounds. This sign may result from overuse of the vocal cords, disorders of the larynx or laryngeal nerves, psychological disorders, or muscle spasm.

Argyll Robertson pupil A small, irregular pupil that constricts normally in accommodation for near vision but poorly or not at all in response to light. Response to mydriatics also is poor or absent. This condition may be unilateral, bilateral, or asymmetrical and most commonly results from chronic syphilitic meningitis or other forms of late syphilis.

arthralgia Joint pain. This symptom may have no pathologic importance or may indicate such disorders as arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

asthenocoria Slow dilation or constriction of the pupils in response to light changes. Photophobia may be present if constriction occurs slowly. Asthenocoria occurs in adrenal insufficiency. It’s also known as

Arroyo’s sign.

asynergy Impaired coordination of muscles or organs that normally function harmoniously. This extrapyramidal symptom stems from disorders of the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

atrophy Shrinkage or wasting away of a tissue or organ due to a reduction in the size or number of its cells. Its etiology may be physiologic, as can be seen in ovary, brain, and skin atrophy, or pathologic, such as atrophy commonly associated with neurologic disorders or spleen, liver, and thyroid abnormalities. This symptom is normally observed using inspection and palpation techniques.

attention span decrease Inability to focus selectively on a task while ignoring extraneous stimuli. Anxiety, emotional upset, and any dysfunction of the central nervous system may decrease the attention span.

autistic behavior Exaggerated self-centered behavior marked by a lack of responsiveness to other people. It’s characterized by highly personalized speech and actions that are not meaningful

to an observer. For example, the patient may rock his or her body or repeatedly bang the head against the floor or wall. Autistic behavior may occur in schizophrenic children and adults.

B

Ballance’s sign A fixed mass or area of dullness found by palpation and percussion of the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It may indicate subcapsular or extracapsular hematoma following splenic rupture.

Ballet’s sign Ophthalmoplegia or paralysis of the external ocular muscles. The patient displays no control of voluntary eye movement but has normal reflexive movement and pupillary light reflexes. This sign is an indicator of thyrotoxicosis.

Barlow’s sign An indicator of congenital dislocation of the hip, detected during the first 6 weeks of life. To elicit this sign, place the infant supine with the hips flexed 90 degrees and the knees fully flexed. Place your palm over the infant’s knee with your thumb in the femoral triangle opposite the lesser trochanter and your index finger over the greater trochanter. Bring the hip into midabduction while gently exerting posterior and lateral pressure with your thumb and posterior and medial pressure with your palm. If you detect a click of the femoral head as it dislocates across the posterior lip of the acetabular socket, you’ve elicited this sign.

Barré’s pyramidal sign Inability to hold the lower legs still with the knees flexed. To detect this sign, help the patient into a prone position, and flex the knees 90 degrees. Then ask him or her to hold the lower legs still. If he or she can’t maintain this position, you’ve observed this sign of pyramidal tract or prefrontal brain disease.

Barré’s sign Delayed contraction of the iris, seen in mental deterioration.

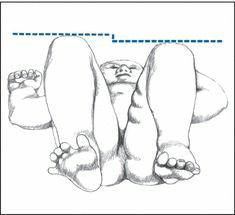

Beau’s lines Transverse white linear depressions on the fingernails. These lines may develop after any severe illness or toxic reaction. Other common causes include malnutrition, nail bed trauma, and coronary artery occlusion.

BEAU’S LINES

Beevor’s sign Upward movement of the umbilicus upon contraction of the abdominal muscles. To detect this sign, help the patient into a supine position, and then ask him or her to sit up. If the umbilicus moves upward, you’ve observed this sign — an indicator of paralysis of the lower