Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

myalgia, and arthralgia. Inspection reveals an exudate on the tonsil or tonsillar fossae, uvular edema, soft palate erythema, and tender cervical lymph nodes.

Also known as thrush, fungal pharyngitis causes diffuse sore throat — commonly described as a burning sensation — accompanied by pharyngeal erythema and edema. White plaques mark the pharynx, tonsil, tonsillar pillars, base of the tongue, and oral mucosa; scraping these plaques uncovers a hemorrhagic base.

With viral pharyngitis, findings include diffuse sore throat, malaise, fever, and mild erythema and edema of the posterior oropharyngeal wall. Tonsillary enlargement may be present along with anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

Sinusitis (acute). Sinusitis may cause sore throat with purulent nasal discharge and postnasal drip, resulting in halitosis. Other effects include headache, malaise, cough, fever, and facial pain and swelling associated with nasal congestion.

Tongue cancer. With tongue cancer, the patient experiences localized throat pain that may occur around a raised white lesion or ulcer. The pain may radiate to the ear and be accompanied by dysphagia.

Tonsillar cancer. Sore throat is the presenting symptom in tonsillar cancer. Unfortunately, the cancer is usually quite advanced before the appearance of this symptom. The pain may radiate to the ear and is accompanied by a superficial ulcer on the tonsil or one that extends to the base of the tongue.

Tonsillitis. With acute tonsillitis, mild to severe sore throat is usually the first symptom. The pain may radiate to the ears and be accompanied by dysphagia and headache. Related findings include malaise, fever with chills, halitosis, myalgia, arthralgia, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Examination reveals edematous, reddened tonsils with a purulent exudate.

Chronic tonsillitis causes mild sore throat, malaise, and tender cervical lymph nodes. The tonsils appear smooth, pink, and, possibly, enlarged, with purulent debris in the crypts. Halitosis and a foul taste in the mouth are other common findings.

Unilateral or bilateral throat pain just above the hyoid bone occurs with lingual tonsillitis. The lingual tonsils appear red and swollen and are covered with exudate. Other findings include a muffled voice, dysphagia, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy on the affected side.

Uvulitis. Uvulitis may cause throat pain or a sensation of something in the throat. The uvula is usually swollen and red but, in allergic uvulitis, it’s pale.

Other Causes

Treatments. Endotracheal intubation and local surgery, such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, commonly cause sore throat.

Special Considerations

Provide analgesic sprays or lozenges to relieve throat pain. Also, prepare the patient for throat culture, complete blood count, and a monospot test.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of completing the full course of antibiotic treatment and discuss ways to soothe the throat.

Pediatric Pointers

Sore throat is a common complaint in children and may result from many of the same disorders that affect adults. Other pediatric causes of sore throat include acute epiglottiditis, herpangina, scarlet fever, acute follicular tonsillitis, and retropharyngeal abscess.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Thyroid Enlargement

An enlarged thyroid can result from inflammation, physiologic changes, iodine deficiency, thyroid tumors, and drugs. Depending on the medical cause, hyperfunction or hypofunction may occur with resulting excess or deficiency, respectively, of the hormone thyroxine. If no infection is present, enlargement is usually slow and progressive. An enlarged thyroid that causes visible swelling in the front of the neck is called a goiter.

History and Physical Examination

The patient’s history commonly reveals the cause of thyroid enlargement. Important data includes a family history of thyroid disease, onset of thyroid enlargement, any previous irradiation of the thyroid or the neck, recent infections, and the use of thyroid replacement drugs.

Begin the physical examination by inspecting the patient’s trachea for midline deviation. Although you can usually see the enlarged gland, you should always palpate it. To palpate the thyroid gland, you’ll need to stand behind the patient. Give the patient a cup of water, and have him extend his neck slightly. Place the fingers of both hands on the patient’s neck, just below the cricoid cartilage and just lateral to the trachea. Tell the patient to take a sip of water and swallow. The thyroid gland should rise as he swallows. Use your fingers to palpate laterally and downward to feel the whole thyroid gland. Palpate over the midline to feel the isthmus of the thyroid.

During palpation, be sure to note the size, shape, and consistency of the gland, and the presence or absence of nodules. Using the bell of a stethoscope, listen over the lateral lobes for a bruit. The bruit is often continuous.

Medical Causes

Hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism is most prevalent in women and usually results from a dysfunction of the thyroid gland, which may be due to surgery, irradiation therapy, chronic autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease), or inflammatory conditions, such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis. Besides an enlarged thyroid, signs and symptoms include weight gain despite anorexia; fatigue; cold intolerance; constipation; menorrhagia; slowed intellectual and motor activity; dry, pale, cool skin; dry, sparse hair; and thick, brittle nails. Eventually, the face assumes a dull expression with periorbital edema.

Iodine deficiency. A goiter may result from a lack of iodine in the diet. If the goiter arises from

a deficiency of iodine in the food or water of a particular area, it’s called an endemic goiter. Associated signs and symptoms of an endemic goiter include dysphagia, dyspnea, and tracheal deviation. This condition is uncommon in developed countries with iodized salt.

Thyroiditis. Thyroiditis, an inflammation of the thyroid gland, may be classified as acute or subacute. It may be due to bacterial or viral infections, in which case associated features include fever and thyroid tenderness. The most prevalent cause of spontaneous hypothyroidism, however, is an autoimmune reaction, as occurs in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Autoimmune thyroiditis usually produces no symptoms other than thyroid enlargement.

Thyrotoxicosis. Overproduction of thyroid hormone causes thyrotoxicosis. The most common form is Graves’ disease, which may result from genetic or immunologic factors. Associated signs and symptoms include nervousness; heat intolerance; fatigue; weight loss despite increased appetite; diarrhea; sweating; palpitations; tremors; smooth, warm, flushed skin; fine, soft hair; exophthalmos; nausea and vomiting due to increased GI motility and peristalsis; and, in females, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea.

Tumors. An enlarged thyroid may result from a malignant tumor or a nonmalignant tumor (such as an adenoma). A malignant tumor usually appears as a single nodule in the neck; a nonmalignant tumor may appear as multiple nodules in the neck. Associated signs and symptoms include hoarseness, loss of voice, and dysphagia.

Thyroid tissue contained in ovarian dermoid tumors can function autonomously or in combination with thyrotoxicosis. Pituitary tumors that secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a rare type, are the only cause of normal or high TSH levels in association with thyrotoxicosis. Finally, high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, as seen in trophoblastic tumors and pregnant women, can cause thyrotoxicosis.

Other Causes

Goitrogens. Goitrogens are drugs — such as lithium, sulfonamides, and para-aminosalicylic acid — and substances in foods that decrease thyroxine production. Foods containing goitrogens include peanuts, cabbage, soybeans, strawberries, spinach, rutabagas, and radishes.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient with an enlarged thyroid for scheduled tests, which may include needle aspiration, ultrasound, and radioactive thyroid scanning. Also prepare him for surgery or radiation therapy, if necessary. If the patient has a goiter, support him as he expresses his feelings related to his appearance.

The hypothyroid patient will need a warm room and moisturizing lotion for his skin. A gentle laxative and stool softener may help with constipation. Provide a high-bulk, low-calorie diet, and encourage activity to promote weight loss. Warn the patient to report any infection immediately; if he develops a fever, monitor his temperature until it’s stable. After thyroid replacement begins, watch for signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as restlessness, sweating, and excessive weight loss. Avoid administering a sedative, if possible, or reduce the dosage because hypothyroidism delays metabolism of many drugs. Check arterial blood gas levels for indications of hypoxia and respiratory acidosis to determine whether the patient needs ventilatory assistance.

For patients with thyroiditis, give an antibiotic and watch for elevations in temperature, which

may indicate developing resistance to the antibiotic. Check vital signs, and examine the patient’s neck for unusual swelling or redness. Provide a liquid diet if the patient has difficulty swallowing. Check for signs of hyperthyroidism, such as nervousness, tremor, and weakness, which are common with subacute thyroiditis. The patient with severe hyperthyroidism (thyroid storm) will need close monitoring of temperature, volume status, heart rate, and blood pressure.

After thyroidectomy, check vital signs every 15 to 30 minutes until the patient’s condition stabilizes. Be alert for signs of tetany secondary to parathyroid injury during surgery. Monitor postoperative serum calcium levels, monitor the patient for a positive Chvostek and Trousseau signs, and keep 10% calcium gluconate available for I.V. use as needed. Evaluate dressings frequently for excessive bleeding, and watch for signs of airway obstruction, such as difficulty in talking, increased swallowing, or stridor. Keep tracheotomy equipment handy.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism to report. Also explain thyroid hormone replacement therapy and signs of thyroid hormone overdose. Discuss posttreatment precautions and the need for radioactive iodine therapy.

Pediatric Pointers

Congenital goiter, a syndrome of infantile myxedema or cretinism, is characterized by mental retardation, growth failure, and other signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism. Early treatment can prevent mental retardation. Genetic counseling is important, as subsequent children are at risk.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Tics

A tic is an involuntary, repetitive movement of a specific group of muscles — usually those of the face, neck, shoulders, trunk, and hands. This sign typically occurs suddenly and intermittently. It may involve a single isolated movement, such as lip smacking, grimacing, blinking, sniffing, tongue thrusting, throat clearing, hitching up one shoulder, or protruding the chin. Or it may involve a complex set of movements. Mild tics, such as twitching of an eyelid, are especially common. Tics differ from minor seizures in that tics aren’t associated with transient loss of consciousness or amnesia.

Tics are usually psychogenic and may be aggravated by stress or anxiety. Psychogenic tics often begin between ages 5 and 10 as voluntary, coordinated, and purposeful actions that the child feels compelled to perform to decrease anxiety. Unless the tics are severe, the child may be unaware of them. The tics may subside as the child matures, or they may persist into adulthood. However, tics are also associated with one rare affliction — Tourette syndrome, which typically begins during childhood.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the parents how long the child has had the tic. How often does the child have the tic? Can they identify any precipitating or exacerbating factors? Can the patient control the tics with conscious effort? Ask about stress in the child’s life such as difficult school work. Next, carefully observe the tic. Is it a purposeful or involuntary movement? Note whether it’s localized or generalized, and describe it in detail.

Medical Causes

Tourette’s syndrome. Tourettes syndrome, which is thought to be largely a genetic disorder, typically begins between ages 2 and 15 with a tic that involves the face or neck. Indications include both motor and vocal tics that may involve the muscles of the shoulders, arms, trunk, and legs. The tics may be associated with violent movements and outbursts of obscenities (coprolalia). The patient snorts, barks, and grunts and may emit explosive sounds, such as hissing, when he speaks. He may involuntarily repeat another person’s words (echolalia) or movements (echopraxia). At times, this syndrome subsides spontaneously or undergoes a prolonged remission, but it may persist throughout life.

Special Considerations

Psychotherapy and administration of a tranquilizer may be helpful in providing relief. Many patients with Tourette’s syndrome receive haloperidol, pimozide, or another antipsychotic to control tics. Help the patient identify and eliminate any avoidable stress and learn positive ways to deal with anxiety. Offer emotional support to the patient and family.

Patient Counseling

Help the patient identify and eliminate any avoidable stress, and discuss positive ways to deal with his anxiety. Offer emotional support.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus literally means ringing in the ears, although many other abnormal sounds fall under this term. For example, tinnitus may be described as the sound of escaping air, running water, the inside of a seashell, or as a sizzling, buzzing, or humming noise. Occasionally, it’s described as a roaring or musical sound. This common symptom may be unilateral or bilateral and constant or intermittent. Although the brain may adjust to or suppress constant tinnitus, tinnitus may be so disturbing that some patients contemplate suicide as their only source of relief.

Tinnitus can be classified in several ways. Subjective tinnitus is heard only by the patient; objective tinnitus is also heard by the observer who places a stethoscope near the patient’s affected ear. Tinnitus aurium refers to noise that the patient hears in his ears; tinnitus cerebri, to noise that he hears in his head.

Tinnitus is usually associated with neural injury within the auditory pathway, resulting in altered, spontaneous firing of sensory auditory neurons. Commonly resulting from an ear disorder, tinnitus may also stem from a cardiovascular or systemic disorder or from the effects of drugs. Nonpathologic

causes of tinnitus include acute anxiety and presbycusis. (See Common Causes of Tinnitus.)

Common Causes of Tinnitus

Tinnitus usually results from a disorder that affects the external, middle, or inner ear. Below are some of its more common causes and their locations.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient to describe the sound he hears, including its onset, pattern, pitch, location, and intensity. Ask whether it’s accompanied by other symptoms, such as vertigo, headache, or hearing loss. Next, take a health history, including a complete drug history.

Using an otoscope, inspect the patient’s ears and examine the tympanic membrane. To check for hearing loss, perform the Weber and Rinne tuning fork tests. (See Differentiating Conductive from Sensorineural Hearing Loss, page 372.)

Also, auscultate for bruits in the neck. Then compress the jugular or carotid artery to see if this affects the tinnitus. Finally, examine the nasopharynx for masses that might cause eustachian tube dysfunction and tinnitus.

Medical Causes

Acoustic neuroma. An early symptom of acoustic neuroma — an eighth cranial nerve tumor — unilateral tinnitus precedes unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo. Facial paralysis, headache, nausea, vomiting, and papilledema may also occur.

Atherosclerosis of the carotid artery. With atherosclerosis of the carotid artery, the patient has constant tinnitus that can be stopped by applying pressure over the carotid artery. Auscultation over the upper part of the neck, on the auricle, or near the ear on the affected side may detect a bruit. Palpation may reveal a weak carotid pulse.

Cervical spondylosis. With degenerative cervical spondylosis, osteophytic growths may compress the vertebral arteries, resulting in tinnitus. Typically, a stiff neck and pain aggravated by activity accompany tinnitus. Other features include brief vertigo, nystagmus, hearing loss, paresthesia, weakness, and pain that radiates down the arms.

Eustachian tube patency. Normally, the eustachian tube remains closed, except during swallowing. However, persistent patency of this tube can cause tinnitus, audible breath sounds, loud and distorted voice sounds, and a sense of fullness in the ear. Examination with a pneumatic otoscope reveals movement of the tympanic membrane with respirations. At times, breath sounds can be heard with a stethoscope placed over the auricle.

Glomus jugulare (tympanicum tumor). A pulsating sound is usually the first symptom of this tumor. Other early features include a reddish blue mass behind the tympanic membrane and progressive conductive hearing loss. Later, total unilateral deafness is accompanied by ear pain and dizziness. Otorrhagia may also occur if the tumor breaks through the tympanic membrane.

Hypertension. Bilateral, high-pitched tinnitus may occur with severe hypertension. Diastolic blood pressure exceeding 120 mm Hg may also cause severe, throbbing headache, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, seizures, and decreased level of consciousness.

Labyrinthitis (suppurative). With labyrinthitis, tinnitus may accompany sudden, severe attacks of vertigo, unilateral or bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, nystagmus, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting.

Ménière’s disease. Most common in adults — especially in men between ages 30 and 60 — Ménière’s disease is a labyrinthine disease that’s characterized by attacks of tinnitus, vertigo, a feeling of fullness or blockage in the ear, and fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss. These attacks last from 10 minutes to several hours; they occur over a few days or weeks and are followed by a remission. Severe nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and nystagmus may also occur during attacks.

Ossicle dislocation. Acoustic trauma, such as a slap on the ear, may dislocate the ossicle, resulting in tinnitus and sensorineural hearing loss. Bleeding from the middle ear may also occur.

Otitis externa (acute). Although not a major complaint with otitis externa, tinnitus may result if debris in the external ear canal impinges on the tympanic membrane. More typical findings include pruritus, foul-smelling purulent discharge, and severe ear pain that’s aggravated by manipulation of the tragus or auricle, teeth clenching, mouth opening, and chewing. The external ear canal typically appears red and edematous and may be occluded by debris, causing partial hearing loss.

Otitis media. Otitis media may cause tinnitus and conductive hearing loss. However, its more

typical features include ear pain, a red and bulging tympanic membrane, high fever, chills, and dizziness.

Otosclerosis. With otosclerosis, the patient may describe ringing, roaring, or whistling tinnitus or a combination of these sounds. He may also report progressive hearing loss, which may lead to bilateral deafness, and vertigo.

Presbycusis. Presbycusis is an otologic effect of aging that produces tinnitus and a progressive, symmetrical, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, usually of high-frequency tones.

Tympanic membrane perforation. With tympanic membrane perforation, tinnitus and hearing loss go hand in hand. Tinnitus is usually the chief complaint in a small perforation; hearing loss is usually the chief complaint in a larger perforation. These symptoms typically develop suddenly and may be accompanied by pain, vertigo, and a feeling of fullness in the ear.

Other Causes

Drugs and alcohol. An overdose of salicylates commonly causes reversible tinnitus. Quinine, alcohol, and indomethacin may also cause reversible tinnitus. Common drugs that may cause irreversible tinnitus include the aminoglycoside antibiotics (especially kanamycin, streptomycin, and gentamicin) and vancomycin.

Noise. Chronic exposure to noise, especially high-pitched sounds, can damage the ear’s hair cells, causing tinnitus and a bilateral hearing loss. These symptoms may be temporary or permanent.

Special Considerations

Tinnitus is typically difficult to treat successfully. After ruling out any reversible causes, it’s important to educate the patient about strategies for adapting to the tinnitus, including biofeedback and masking devices.

In addition, a hearing aid may be prescribed to amplify environmental sounds, thereby obscuring tinnitus. For some patients, a device that combines features of a masker and a hearing aid may be used to block out tinnitus.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of avoiding excessive noise, ototoxic agents, and other factors that may cause cochlear damage. Educate the patient about strategies for adapting to tinnitus, including biofeedback and masking devices.

Pediatric Pointers

An expectant mother’s use of ototoxic drugs during the third trimester of pregnancy can cause labyrinthine damage in the fetus, resulting in tinnitus. Many of the disorders described above can also cause tinnitus in children.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Tracheal Deviation

Normally, the trachea is located at the midline of the neck — except at the bifurcation, where it shifts slightly toward the right. Visible deviation from its normal position signals an underlying condition that can compromise pulmonary function and possibly cause respiratory distress. A hallmark of lifethreatening tension pneumothorax, tracheal deviation occurs with disorders that produce mediastinal shift due to asymmetrical thoracic volume or pressure. A nonlesion pneumothorax can produce tracheal deviation to the ipsilateral side. (See Detecting Slight Tracheal Deviation.)

Emergency Interventions

Be alert for signs and symptoms of respiratory distress (tachypnea, dyspnea, decreased or absent breath sounds, stridor, nasal flaring, accessory muscle use, asymmetrical chest expansion, restlessness, and anxiety). If possible, place the patient in semi-Fowler’s position to aid respiratory excursion and improve oxygenation. Give supplemental oxygen, and intubate the patient if necessary. Insert an I.V. line for fluid and drug administration. In addition, palpate for subcutaneous crepitation in the neck and chest, a sign of tension pneumothorax. Chest tube insertion may be necessary to release trapped air or fluid and to restore normal intrapleural and intrathoracic pressure gradients.

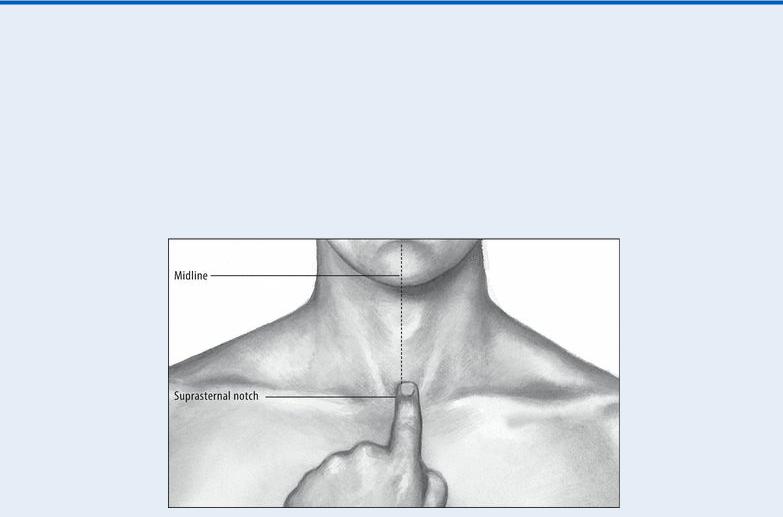

EXAMINATION TIP Detecting Slight Tracheal Deviation

Although gross tracheal deviation is visible, detection of slight deviation requires palpation and perhaps even an X-ray. Try palpation first.

With the tip of your index finger, locate the patient’s trachea by palpating between the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Then compare the trachea’s position to an imaginary line drawn vertically through the suprasternal notch. Any deviation from midline is usually considered abnormal.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient doesn’t display signs of distress, ask about a history of pulmonary or cardiac disorders, surgery, trauma, or infection. If he smokes, determine how much. Ask about associated signs and symptoms, especially breathing difficulty, pain, and cough.

Medical Causes

Atelectasis. Extensive lung collapse can produce tracheal deviation toward the affected side. Respiratory findings include dyspnea, tachypnea, pleuritic chest pain, dry cough, dullness on percussion, decreased vocal fremitus and breath sounds, inspiratory lag, and substernal or intercostal retraction.

Hiatal hernia. Intrusion of abdominal viscera into the pleural space causes tracheal deviation toward the unaffected side. The degree of attendant respiratory distress depends on the extent of herniation. Other effects include pyrosis, regurgitation or vomiting, and chest or abdominal pain. Kyphoscoliosis. Kyphoscoliosis can cause rib cage distortion and mediastinal shift, producing tracheal deviation toward the compressed lung. Respiratory effects include dry coughing, dyspnea, asymmetrical chest expansion, and, possibly, asymmetrical breath sounds. Backache and fatigue are also common.

Mediastinal tumor. Often producing no symptoms in its early stages, a mediastinal tumor, when large, can press against the trachea and nearby structures, causing tracheal deviation and dysphagia. Other late findings include stridor, dyspnea, brassy cough, hoarseness, and stertorous respirations with suprasternal retraction. The patient may experience shoulder, arm, or chest pain as well as edema of the neck, face, or arm. His neck and chest wall veins may be dilated.

Pulmonary tuberculosis. With a large cavitation, tracheal deviation toward the affected side accompanies asymmetrical chest excursion, dullness on percussion, increased tactile fremitus, amphoric breath sounds, and inspiratory crackles. Insidious early effects include fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, fever, chills, and night sweats. Productive cough, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea develop as the disease progresses.

Retrosternal thyroid. Retrosternal thyroid — an anatomic abnormality — can displace the trachea. The gland is felt as a movable neck mass above the suprasternal notch. Dysphagia, cough, hoarseness, and stridor are common. Signs of thyrotoxicosis may be present.

Tension pneumothorax. Tension pneumothorax is an acute, life-threatening condition that produces tracheal deviation toward the unaffected side. It’s marked by a sudden onset of respiratory distress with sharp chest pain, dry cough, severe dyspnea, tachycardia, wheezing, cyanosis, accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, air hunger, and asymmetrical chest movement. Restless and anxious, the patient may also develop subcutaneous crepitation in the neck and upper chest, decreased vocal fremitus, decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side, jugular vein distention, and hypotension.

Thoracic aortic aneurysm. Thoracic aortic aneurysm usually causes the trachea to deviate to the right. Highly variable associated findings may include stridor, dyspnea, wheezing, brassy cough, hoarseness, and dysphagia. Edema of the face, neck, or arm may occur with distended