Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

hands, feet, arms, legs, buttocks, and trunk. Initially, networking is intermittent and most pronounced on exposure to cold or stress; eventually, mottling persists even with warming. Periarteritis nodosa. Skin findings in periarteritis nodosa include asymmetrical, patchy livedo reticularis, palpable nodules along the path of medium-sized arteries, erythema, purpura, muscle wasting, ulcers, gangrene, peripheral neuropathy, a fever, weight loss, and malaise. Polycythemia vera. Polycythemia vera is a hematologic disorder that produces livedo reticularis, hemangiomas, purpura, rubor, ulcerative nodules, and scleroderma-like lesions. Other symptoms include a headache, a vague feeling of fullness in the head, dizziness, vertigo, vision disturbances, dyspnea, and aquagenic pruritus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is a connective tissue disorder that can cause livedo reticularis, most commonly on the outer arms. Other signs and symptoms include a butterfly rash, nondeforming joint pain and stiffness, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, patchy alopecia, seizures, a fever, anorexia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, and emotional lability.

Other Causes

Immobility. Prolonged immobility may cause bluish mottling, most noticeably in dependent extremities.

Thermal exposure. Prolonged thermal exposure, as from a heating pad or hot water bottle, may cause erythema ab igne — a localized, reticulated, brown-to-red mottling.

Special Considerations

Mottled skin typically results from a chronic condition. Provide care to treat the underlying condition.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient to avoid wearing tight-fitting clothing and overexposure to cold and heating devices. Teach him to recognize flare-ups of the underlying condition.

Pediatric Pointers

A common cause of mottled skin in children is systemic vasoconstriction from shock. Other causes are the same as those for adults.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, decreased tissue perfusion can easily cause mottled skin. Besides arterial occlusion and polycythemia vera, conditions that commonly affect patients in this age group, bowel ischemia is typical in elderly patients who present with livedo reticularis, especially if they also have abdominal pain or bloody stools.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults

and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Skin, Scaly

Scaly skin results when cells of the uppermost skin layer (stratum corneum) desiccate and shed, causing excessive accumulation of loosely adherent flakes of normal or abnormal keratin. Normally, skin cell loss is imperceptible; the appearance of scale indicates increased cell proliferation secondary to altered keratinization.

Scaly skin varies in texture from fine and delicate to branlike, coarse, or stratified. Scales are typically dry, brittle, and shiny, but they can be greasy and dull. Their color ranges from whitish gray, yellow, or brown to a silvery sheen.

Usually benign, scaly skin occurs with fungal, bacterial, and viral infections (cutaneous or systemic), lymphomas, and lupus erythematosus; it’s also common in those with inflammatory skin disease. A form of scaly skin — generalized fine desquamation — commonly follows prolonged febrile illness, sunburn, and thermal burns. Red patches of scaly skin that appear or worsen in winter may result from dry skin (or from actinic keratosis, common in elderly patients). Certain drugs also cause scaly skin. Aggravating factors include cold, heat, immobility, and frequent bathing.

History and Physical Examination

Begin the history by asking how long the patient has had scaly skin and whether he has had it before. Where did it first appear? Did a lesion or skin eruption, such as erythema, precede it? Has the patient used a new or different topical skin product recently? How often does he bathe? Has he had recent joint pain, illness, or malaise? Ask the patient about work exposure to chemicals, use of prescribed drugs, and a family history of skin disorders. Find out what kinds of soap, cosmetics, skin lotion, and hair preparations he uses.

Next, examine the entire skin surface. Is it dry, oily, moist, or greasy? Observe the general pattern of skin lesions, and record their location. Note their color, shape, and size. Are they thick or fine? Do they itch? Does the patient have other lesions besides scaly skin? Examine the mucous membranes of his mouth, lips, and nose, and inspect his ears, hair, and nails.

Medical Causes

Bowen’s disease . Bowen’s disease is a common form of intraepidermal carcinoma that causes painless, erythematous plaques that are raised and indurated with a thick, hyperkeratotic scale and, possibly, ulcerated centers.

Dermatitis. Exfoliative dermatitis begins with rapidly developing generalized erythema. Desquamation with fine scales or thick sheets of all or most of the skin surface may cause lifethreatening hypothermia. Other possible complications include cardiac output failure and septicemia. Systemic signs and symptoms include a low-grade fever, chills, malaise, lymphadenopathy, and gynecomastia.

With nummular dermatitis, round, pustular lesions commonly ooze purulent exudate, itch severely, and rapidly become encrusted and scaly. Lesions appear on the extensor surfaces of the limbs, posterior trunk, and buttocks.

Seborrheic dermatitis begins with erythematous, scaly papules that progress to larger, dry or

moist, greasy scales with yellowish crusts. This disorder primarily involves the center of the face, the chest and scalp, and, possibly, the genitalia, axillae, and perianal regions. Pruritus occurs with scaling.

Dermatophytosis. Tinea capitis produces lesions with reddened, slightly elevated borders and a central area of dense scaling; these lesions may become inflamed and pus-filled (kerions). Patchy alopecia and itching may also occur. Tinea pedis causes scaling and blisters between the toes. The squamous type produces diffuse, fine, branlike scales. Adherent and silvery white, they’re most prominent in skin creases and may affect the entire dorsum of the foot. Tinea corporis produces crusty lesions. As they enlarge, their centers heal, causing the classic ringworm shape.

Lymphoma. Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma commonly cause scaly rashes. Hodgkin’s disease may cause pruritic scaling dermatitis that begins in the legs and spreads to the entire body. Remissions and recurrences are common. Small nodules and diffuse pigmentation are related signs. This disease typically produces painless enlargement of the peripheral lymph nodes. Other signs and symptoms include a fever, fatigue, weight loss, malaise, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma initially produces erythematous patches with some scaling that later become interspersed with nodules. Pruritus and discomfort are common; later, tumors and ulcers form. Progression produces nontender lymphadenopathy.

Parapsoriasis (chronic). Parapsoriasis produces small or moderate-sized maculopapular, erythematous eruptions, with a thin, adherent scale on the trunk, hands, and feet. Removal of the scale reveals a shiny brown surface.

Pityriasis. Pityriasis rosea, an acute, benign, and self-limiting disorder, produces widespread scales. It begins with an erythematous, raised, oval herald patch anywhere on the body. A few days or weeks later, yellow-tan or erythematous patches with scaly edges erupt on the trunk and limbs and sometimes on the face, hands, and feet. Pruritus also occurs.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris, an uncommon disorder, initially produces seborrheic scaling on the scalp, progressing to the face and ears. Later, scaly red patches develop on the palms and soles, becoming diffuse, thick, fissured, hyperkeratotic, and painful. Lesions also appear on the hands, fingers, wrists, and forearms and then on wide areas of the trunk, neck, and limbs.

Psoriasis. Silvery white, micaceous scales cover erythematous plaques that have sharply defined borders. Psoriasis usually appears on the scalp, chest, elbows, knees, back, buttocks, and genitalia. Associated signs and symptoms include nail pitting, pruritus, arthritis, and sometimes pain from dry, cracked, encrusted lesions.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE produces a bright-red maculopapular eruption, sometimes with scaling. Patches are sharply defined and involve the nose and malar regions of the face in a butterfly pattern — a primary sign. Similar characteristic rashes appear on other body surfaces; scaling occurs along the lower lip or anterior hairline. Other primary signs and symptoms include photosensitivity and joint pain and stiffness. Vasculitis (leading to infarctive lesions, necrotic leg ulcers, or digital gangrene), Raynaud’s phenomenon, patchy alopecia, and mucous membrane ulcers can also occur.

Tinea versicolor. Tinea versicolor is a benign fungal skin infection that typically produces macular hypopigmented, fawn-colored, or brown patches of varying sizes and shapes. All are slightly scaly. Lesions commonly affect the upper trunk, arms, and lower abdomen; sometimes the neck; and, rarely, the face.

Other Causes

Drugs. Many drugs — including penicillins, sulfonamides, barbiturates, quinidine, diazepam, phenytoin, and isoniazid — can produce scaling patches.

Special Considerations

If scaling results from corticosteroid therapy, wean the patient off the drug. Prepare the patient for such diagnostic tests as a Wood’s light examination, skin scraping, and skin biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient or caregiver in proper skin care, and explain the treatment of the underlying disorder.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, scaly skin may stem from infantile eczema, pityriasis rosea, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, psoriasis, various forms of ichthyosis, atopic dermatitis, a viral infection (especially hepatitis B virus, which can cause Gianotti-Crosti syndrome), seborrhea capitis (cradle cap), or an acute transient dermatitis. Desquamation may follow a febrile illness.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Skin Turgor, Decreased

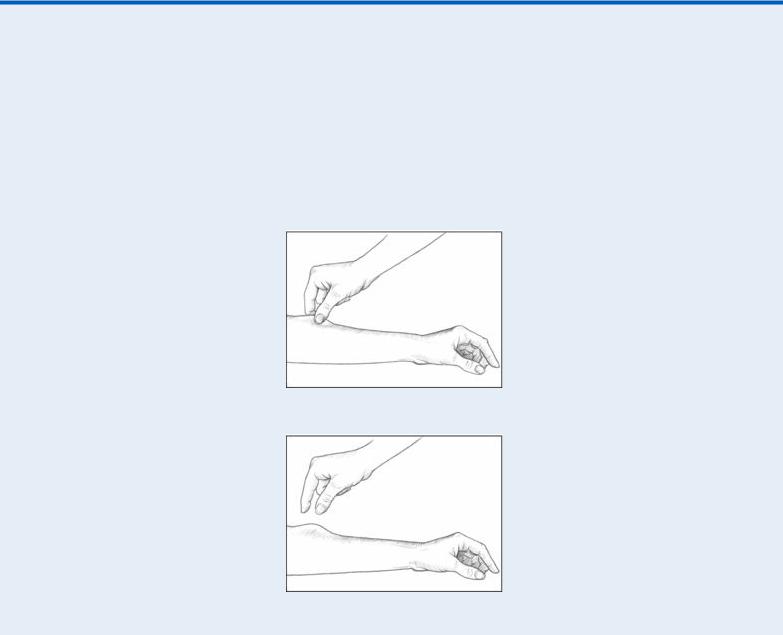

Skin turgor — the skin’s elasticity — is determined by observing the time required for the skin to return to its normal position after being stretched or pinched. With decreased turgor, pinched skin “holds” for up to 30 seconds and then slowly returns to its normal contour. Skin turgor is commonly assessed over the hand, arm, or sternum — areas normally free from wrinkles and with wide variations in tissue thickness. (See Evaluating Skin Turgor, page 670.)

Decreased skin turgor results from dehydration, or volume depletion, which moves interstitial fluid into the vascular bed to maintain circulating blood volume, leading to slackness in the skin’s dermal layer. It’s a normal finding in elderly patients and in people who have lost weight rapidly; it also occurs with disorders affecting the GI, renal, endocrine, and other systems.

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Skin Turgor

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Skin Turgor

To evaluate skin turgor in an adult, pick up a fold of skin over the sternum or the arm, as shown below left. (In an infant, roll a fold of loosely adherent skin on the abdomen between your thumb and forefinger.) Then, release it. Normal skin will immediately return to its previous contour. In decreased skin turgor, the skin fold will “hold,” or “tent,” as shown below right, for up to 30 seconds.

History and Physical Examination

If your examination reveals decreased skin turgor, ask the patient about food and fluid intake and fluid loss. Has he recently experienced prolonged fluid loss from vomiting, diarrhea, draining wounds, or increased urination? Has he recently had a fever with sweating? Is the patient taking a diuretic? If so, how often? Does he frequently use alcohol?

Next, take the patient’s vital signs. Note if his systolic blood pressure is abnormally low (90 mm Hg or less) when he’s in a supine position, if it drops 15 to 20 mm Hg or more when he stands, or if his pulse increases by 10 beats/minute when he sits or stands. If you detect these signs of orthostatic hypotension or resting tachycardia, start an I.V. line for fluids.

Evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) for confusion, disorientation, and signs of profound dehydration. Inspect his oral mucosa, the furrows of his tongue (especially under the tongue), and his axillae for dryness. Also, check his jugular veins for flatness, and monitor his urine output.

Medical Causes

Cholera. Cholera is characterized by abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting, which leads to severe water and electrolyte loss. These imbalances cause the following symptoms: decreased skin turgor, thirst, weakness, muscle cramps, oliguria, tachycardia, and hypotension. Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

Dehydration. Decreased skin turgor commonly occurs with moderate to severe dehydration. Associated findings include dry oral mucosa, decreased perspiration, resting tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, a dry and furrowed tongue, increased thirst, weight loss, oliguria, a fever, and fatigue. As dehydration worsens, other findings include enophthalmos, lethargy, weakness, confusion, delirium or obtundation, anuria, and shock. Hypotension persists even when the patient lies down.

Special Considerations

Even a small deficit in body fluid may be critical in patients with diminished total body fluid — young children, elderly people, obese people, and people who have rapidly lost a large amount of weight.

To prevent skin breakdown in a dehydrated patient with poor skin turgor, a decreased LOC, and impaired peripheral circulation, turn him every 2 hours, and frequently massage his back and pressure points. Monitor his intake and output, administer I.V. fluids, and frequently offer oral fluids. Weigh the patient daily at the same time on the same scale. Be alert for urine output that falls below 30 mL/hour and for continued weight loss. Also, closely monitor the patient for signs of electrolyte imbalance.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of fluid replacement and which signs and symptoms the patient should report.

Pediatric Pointers

Diarrhea secondary to gastroenteritis is the most common cause of dehydration in children, especially up to age 2.

Geriatric Pointers

Because it’s a natural part of the aging process, decreased skin turgor may be an unreliable physical finding in elderly patients. Other signs of volume depletion — such as dry oral mucosa, dry axillae, decreased urine output, or hypotension — must also be carefully evaluated.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Splenomegaly

Because it occurs with various disorders and in up to 5% of normal adults, splenomegaly — an enlarged spleen — isn’t a diagnostic sign by itself. Usually, however, it points to infection, trauma, or a hepatic, autoimmune, neoplastic, or hematologic disorder.

Because the spleen functions as the body’s largest lymph node, splenomegaly can result from any process that triggers lymphadenopathy. For example, it may reflect reactive hyperplasia (a response to infection or inflammation), proliferation or infiltration of neoplastic cells, extramedullary hemopoiesis, phagocytic cell proliferation, increased blood cell destruction, or vascular congestion associated with portal hypertension.

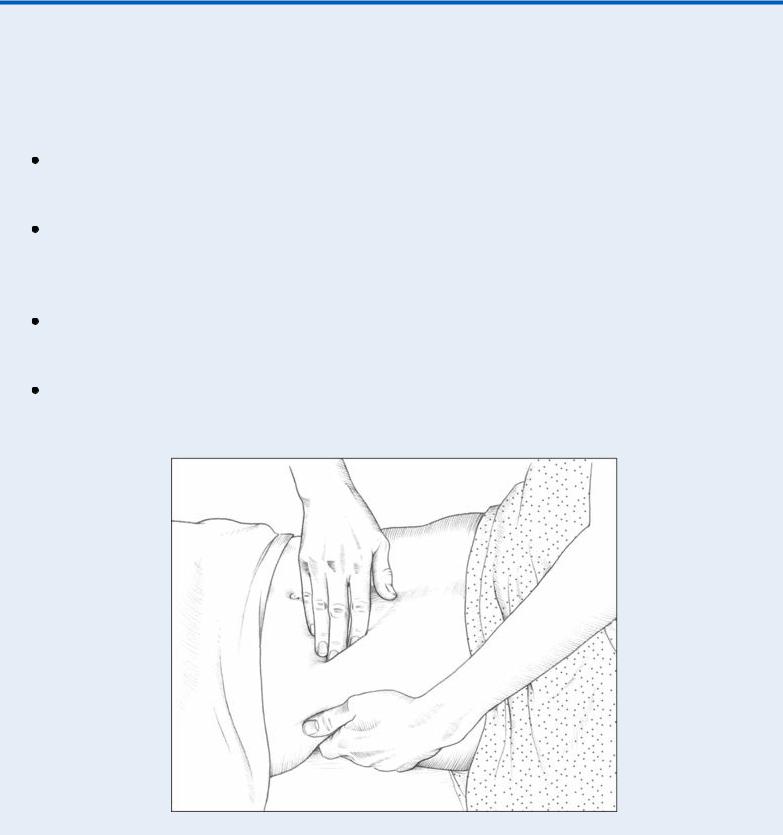

EXAMINATION TIP How to Palpate for Splenomegaly

EXAMINATION TIP How to Palpate for Splenomegaly

Detecting splenomegaly requires skillful and gentle palpation to avoid rupturing the enlarged spleen. Follow these steps carefully:

Place the patient in the supine position, and stand at her right side. Place your left hand under the left costovertebral angle, and push lightly to move the spleen forward. Then, press your right hand gently under the left front costal margin.

Have the patient take a deep breath and then exhale. As she exhales, move your right hand along the tissue contours under the border of the ribs, feeling for the spleen’s edge. The enlarged spleen should feel like a firm mass that bumps against your fingers. Remember to begin palpation low enough in the abdomen to catch the edge of a massive spleen.

Grade the splenomegaly as slight (½ to 1½″ [1 to 4 cm] below the costal margin), moderate (1½ to 3″ [4 to 8 cm] below the costal margin), or great (greater than or equal to 3″ [8 cm] below the costal margin).

Reposition the patient on her right side with her hips and knees flexed slightly to move the spleen forward. Then, repeat the palpation procedure.

Splenomegaly may be detected by light palpation under the left costal margin. (See How to Palpate for Splenomegaly.) However, because this technique isn’t always advisable or effective, splenomegaly may need to be confirmed by a computed tomography or radionuclide scan.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has a history of abdominal or thoracic trauma, don’t palpate the abdomen because this may aggravate internal bleeding. Instead, examine him for left upper quadrant pain and signs of shock, such as tachycardia and tachypnea. If you detect these signs, suspect splenic rupture. Insert an I.V. line for emergency fluid and blood replacement, and administer oxygen. Also, catheterize the patient to evaluate urine output, and begin cardiac monitoring. Prepare the patient for possible surgery.

History and Physical Examination

If you detect splenomegaly during a routine physical examination, begin by exploring associated signs and symptoms. Ask the patient if he has been unusually tired lately. Does he frequently have colds, sore throats, or other infections? Does he bruise easily? Ask about left upper quadrant pain, abdominal fullness, and early satiety. Finally, examine the patient’s skin for pallor and ecchymoses, and palpate his axillae, groin, and neck for lymphadenopathy.

Medical Causes

Brucellosis. With severe cases of brucellosis, a rare infection, splenomegaly is a major sign. Typically, brucellosis begins insidiously with fatigue, a headache, a backache, anorexia, arthralgia, a fever, chills, sweating, and malaise. Later, it may cause hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, and vertebral or peripheral nerve pain on pressure.

Cirrhosis. About one-third of patients with advanced cirrhosis develop moderate to marked splenomegaly. Among other late findings are jaundice, hepatomegaly, leg edema, hematemesis, and ascites. Signs of hepatic encephalopathy — such as asterixis, fetor hepaticus, slurred speech, and a decreased level of consciousness that may progress to coma — are also common. Besides jaundice, skin effects may include severe pruritus, poor tissue turgor, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, pallor, and signs of bleeding tendencies. Endocrine effects may include menstrual irregularities or testicular atrophy, gynecomastia, and a loss of chest and axillary hair. The patient may also develop a fever and right upper abdominal pain that’s aggravated by sitting up or leaning forward.

Felty’s syndrome . Splenomegaly is characteristic in Felty’s syndrome, which occurs with chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Associated findings are joint pain and deformity, sensory or motor loss, rheumatoid nodules, palmar erythema, lymphadenopathy, and leg ulcers.

Histoplasmosis. Acute disseminated histoplasmosis commonly produces splenomegaly and hepatomegaly. It may also cause lymphadenopathy, jaundice, a fever, anorexia, emaciation, and

signs and symptoms of anemia, such as weakness, fatigue, pallor, and malaise. Occasionally, the patient’s tongue, palate, epiglottis, and larynx become ulcerated, resulting in pain, hoarseness, and dysphagia.

Leukemia. Moderate to severe splenomegaly is an early sign of acute and chronic leukemia. With chronic granulocytic leukemia, splenomegaly is sometimes painful. Accompanying it may be hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, fatigue, malaise, pallor, a fever, gum swelling, bleeding tendencies, weight loss, anorexia, and abdominal, bone, and joint pain. At times, acute leukemia also causes dyspnea, tachycardia, and palpitations. With advanced disease, the patient may display confusion, a headache, vomiting, seizures, papilledema, and nuchal rigidity.

Mononucleosis (infectious). A common sign of mononucleosis, splenomegaly is most pronounced during the second and third weeks of illness. Typically, it’s accompanied by a triad of signs and symptoms: a sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, and fluctuating temperature with an evening peak of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C). Occasionally, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and a maculopapular rash may also occur.

Pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic cancer may cause moderate to severe splenomegaly if tumor growth compresses the splenic vein. Other characteristic findings include abdominal or back pain, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, GI bleeding, jaundice, pruritus, skin lesions, emotional lability, weakness, and fatigue. Palpation may reveal a tender abdominal mass and hepatomegaly; auscultation reveals a bruit in the periumbilical area and left upper quadrant.

Polycythemia vera. Late in polycythemia vera, the spleen may become markedly enlarged, resulting in easy satiety, abdominal fullness, and left upper quadrant or pleuritic chest pain. Signs and symptoms accompanying splenomegaly are widespread and numerous. The patient may exhibit deep, purplish red oral mucous membranes, a headache, dyspnea, dizziness, vertigo, weakness, and fatigue. He may also develop finger and toe paresthesia, impaired mentation, tinnitus, blurred or double vision, scotoma, increased blood pressure, and intermittent claudication. Other signs and symptoms include pruritus, urticaria, ruddy cyanosis, epigastric distress, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and bleeding tendencies.

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disorder that may produce splenomegaly and hepatomegaly, possibly accompanied by vague abdominal discomfort. Its other signs and symptoms vary with the affected body system, but may include a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, malaise, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, skin lesions, an irregular pulse, impaired vision, dysphagia, and seizures.

Splenic rupture. Splenomegaly may result from massive hemorrhage with splenic rupture. The patient may also experience left upper quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity, and Kehr’s sign. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura may produce splenomegaly and hepatomegaly accompanied by fever, generalized purpura, jaundice, pallor, vaginal bleeding, and hematuria. Other effects include fatigue, weakness, a headache, pallor, abdominal pain, and arthralgia. Eventually, the patient develops signs of neurologic deterioration and renal failure.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as a complete blood count, blood cultures, and radionuclide and computed tomography scans of the spleen.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient how to avoid infection, and emphasize the importance of complying with drug therapy.

Pediatric Pointers

Besides the causes of splenomegaly described above, children may develop splenomegaly in histiocytic disorders, congenital hemolytic anemia, Gaucher’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease, hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell disease, or beta-thalassemia (Cooley’s anemia). Splenic abscess is the most common cause of splenomegaly in immunocompromised children.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Stools, Clay Colored

Pale, putty-colored stools usually result from hepatic, gallbladder, or pancreatic disorders. Normally, bile pigments give the stool its characteristic brown color. However, hepatocellular degeneration or biliary obstruction may interfere with the formation or release of these pigments into the intestine, resulting in clay-colored stools. These stools are commonly associated with jaundice and dark “colacolored” urine.

History and Physical Examination

After documenting when the patient first noticed clay-colored stools, explore associated signs and symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and dark urine. Does the patient have trouble digesting fatty foods or heavy meals? Does he bruise easily?

Next, review the patient’s medical history for gallbladder, hepatic, or pancreatic disorders. Has he ever had biliary surgery? Has he recently undergone barium studies? (Barium lightens stool color for several days.) Also, ask about antacid use because large amounts may lighten stool color. Note a history of alcoholism or exposure to other hepatotoxic substances.

After assessing the patient’s general appearance, take his vital signs and check his skin and eyes for jaundice. Then, examine the abdomen: Inspect for distention and ascites, and auscultate for hypoactive bowel sounds. Percuss and palpate for masses and rebound tenderness. Finally, obtain urine and stool specimens for laboratory analysis.

Medical Causes

Bile duct cancer. Commonly a presenting sign of bile duct cancer, clay-colored stools may be accompanied by jaundice, pruritus, anorexia and weight loss, upper abdominal pain, bleeding tendencies, and a palpable mass.