Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE

Because dyspnea is subjective and can be exacerbated by anxiety, listening carefully to the words the patient uses to describe his dyspnea may help determine the underlying cause. Be

aware that patients from different cultures may use different words or phrases to describe their dyspnea.

During the physical examination, look for signs of chronic dyspnea such as accessory muscle hypertrophy (especially in the shoulders and neck). Also look for pursed-lip exhalation, clubbing, peripheral edema, barrel chest, diaphoresis, and jugular vein distention.

Check blood pressure, and auscultate for crackles, abnormal heart sounds or rhythms, egophony, bronchophony, and whispered pectoriloquy. Finally, palpate the abdomen for hepatomegaly, and assess the patient for edema.

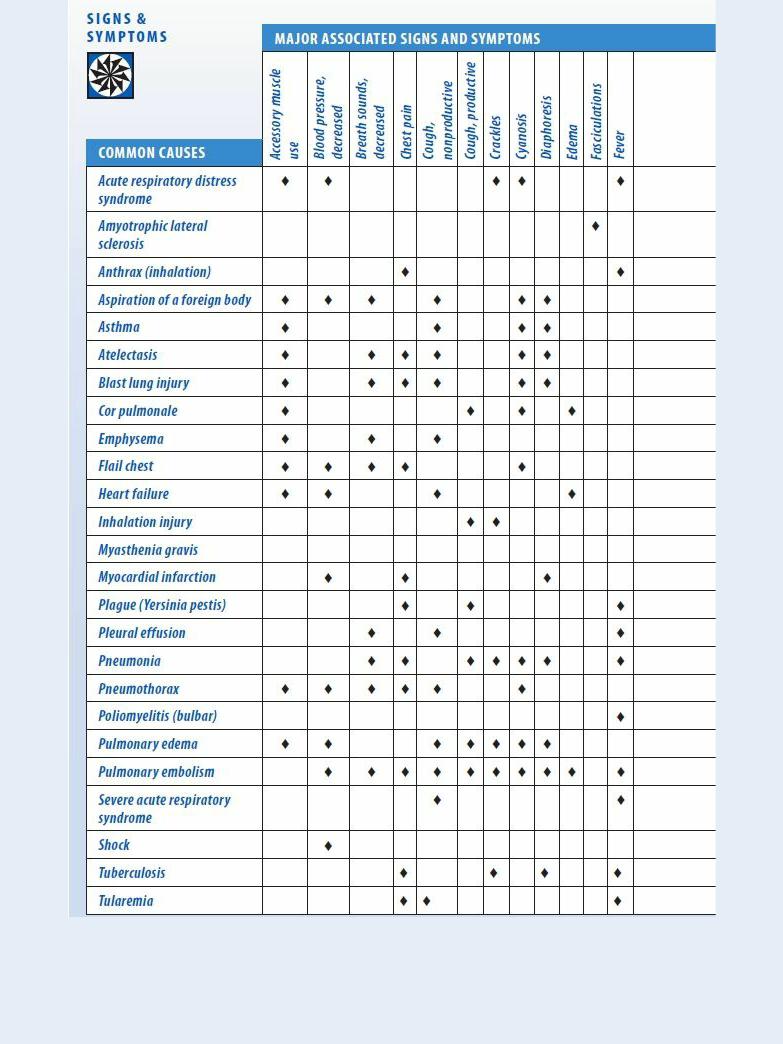

Medical Causes

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is a life-threatening form of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema that usually produces acute dyspnea as the first complaint. Progressive respiratory distress then develops with restlessness, anxiety, decreased mental acuity, tachycardia, and crackles and rhonchi in both lung fields. Other findings include cyanosis, tachypnea, motor dysfunction, and intercostal and suprasternal retractions. Severe ARDS can produce signs of shock, such as hypotension and cool, clammy skin.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS causes the slow onset of dyspnea that worsens with time. Other features include dysphagia, dysarthria, muscle weakness and atrophy, fasciculations, shallow respirations, tachypnea, and emotional lability.

Anthrax (inhalation). Dyspnea is a symptom of the second stage of anthrax, along with a fever, stridor, and hypotension (the patient usually dies within 24 hours). Initial symptoms of this disorder, which are due to the inhalation of aerosolized spores (from infected animals or as a result of bioterrorism) from the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, are flulike and include a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain.

Aspiration of a foreign body. Acute dyspnea marks this life-threatening condition, along with paroxysmal intercostal, suprasternal, and substernal retractions. The patient may also display accessory muscle use, inspiratory stridor, tachypnea, decreased or absent breath sounds, possibly asymmetrical chest expansion, anxiety, cyanosis, diaphoresis, and hypotension.

Asthma. Acute dyspneic attacks occur with asthma, along with audible wheezing, a dry cough, accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions, tachypnea, tachycardia, diaphoresis, prolonged expiration, flushing or cyanosis, and apprehension. Medications that block beta-receptors can exacerbate asthma attacks.

Atelectasis. In atelectasis, part or all of a lung is collapsed, resulting in decreased lung expansion. The patient experiences dyspnea and shortness of breath. Accompanying symptoms may include anxiety, tachycardia, cyanosis, diaphoresis, and a dry cough. A chest X-ray that shows the collapsed area confirms the diagnosis, along with physical examination findings of dullness to percussion, auscultation of decreased breath sounds, decreased vocal fremitus, inspiratory lag, and chest retractions.

Blast lung injury. People affected with a blast lung injury may experience a sudden onset of dyspnea following detonation of an explosive device that strews pieces of metal and chemical irritants toward them at a high velocity. Treatment for dyspnea should be immediate as prolonged dyspnea could result in poor oxygenation. Other symptoms include severe chest pain, skin tears and contusions, edema, hemorrhage of the lungs, hemoptysis, cough, tachypnea,

hypoxia, wheezing, apnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and hemodynamic instability. Global acts of terrorism have increased the incidence of this condition. Chest X-rays, arterial blood gas measurements, computerized tomography scans, and Doppler technology are common diagnostic tools. Although there are no definitive guidelines for caring for those with blast lung injury, treatment is based on the nature of the explosion, the environment in which it occurred, and any chemical or biological agents involved.

Cor pulmonale. Chronic dyspnea begins gradually with exertion and progressively worsens until it occurs even at rest. Underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease is usually present. The patient may have a chronic productive cough, wheezing, tachypnea, jugular vein distention, dependent edema, and hepatomegaly. He may also experience increasing fatigue, weakness, and light-headedness.

Emphysema. Emphysema is a chronic disorder that gradually causes progressive exertional dyspnea. A history of smoking, an alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, or exposure to an occupational irritant usually accompanies barrel chest, accessory muscle hypertrophy, diminished breath sounds, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, peripheral cyanosis, tachypnea, pursed-lip breathing, prolonged expiration and, possibly, a chronic productive cough. Clubbing is a late sign.

Flail chest. Sudden dyspnea results from multiple rib fractures and is accompanied by paradoxical chest movement, severe chest pain, hypotension, tachypnea, tachycardia, and cyanosis. Bruising and decreased or absent breath sounds occur over the affected side.

Heart failure. Dyspnea usually develops gradually in patients with heart failure. Chronic paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, palpitations, a ventricular gallop, fatigue, dependent peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, a dry cough, weight gain, and loss of mental acuity may occur. With acute onset, heart failure may produce jugular vein distention, bibasilar rates, oliguria, and hypotension.

Inhalation injury. Dyspnea may develop suddenly or gradually over several hours after the inhalation of chemicals or hot gases. Increasing hoarseness, a persistent cough, sooty or bloody sputum, and oropharyngeal edema may also be present. The patient may also exhibit thermal burns, singed nasal hairs, and orofacial burns, as well as crackles, rhonchi, wheezing, and signs of respiratory distress.

Myasthenia gravis. Myasthenia gravis causes bouts of dyspnea as the respiratory muscles weaken. With myasthenic crisis, acute respiratory distress may occur, with shallow respirations and tachypnea.

Myocardial infarction. Sudden dyspnea occurs with crushing substernal chest pain that may radiate to the back, neck, jaw, and arms. Other signs and symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, vertigo, hypertension or hypotension, tachycardia, anxiety, and pale, cool, clammy skin.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). Among the symptoms of the pneumonic form of plague are dyspnea, a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency. The onset of this virulent infection is usually sudden and includes such signs and symptoms as chills, a fever, a headache, and myalgia. If untreated, plague is one of the most potentially lethal diseases known.

Pleural effusion. Dyspnea develops slowly and becomes progressively worse with pleural effusion. Initial findings include a pleural friction rub accompanied by pleuritic pain that worsens with coughing or deep breathing. Other findings include a dry cough; dullness on

percussion; egophony, bronchophony, and whispered pectoriloquy; tachycardia; tachypnea; weight loss; and decreased chest motion, tactile fremitus, and decreased breath sounds. With infection, a fever may occur.

Pneumonia. Dyspnea occurs suddenly, usually accompanied by a fever, shaking chills, pleuritic chest pain that worsens with deep inspiration, and a productive cough. Fatigue, a headache, myalgia, anorexia, abdominal pain, crackles, rhonchi, tachycardia, tachypnea, cyanosis, decreased breath sounds, and diaphoresis may also occur.

Pneumothorax. Pneumothorax is a life-threatening disorder that causes acute dyspnea unrelated to the severity of the pain. Sudden, stabbing chest pain may radiate to the arms, face, back, or abdomen. Other signs and symptoms include anxiety, restlessness, a dry cough, cyanosis, decreased vocal fremitus, tachypnea, tympany, decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side, asymmetrical chest expansion, splinting, and accessory muscle use. In patients with tension pneumothorax, tracheal deviation occurs in addition to these typical findings. Decreased blood pressure and tachycardia may also occur.

Poliomyelitis (bulbar). Dyspnea develops gradually and progressively worsens. Additional signs and symptoms include a fever, facial weakness, dysphasia, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes, decreased mental acuity, dysphagia, nasal regurgitation, and hypopnea.

Pulmonary edema. Commonly preceded by signs of heart failure, such as jugular vein distention and orthopnea, pulmonary edema — a life-threatening disorder — causes acute dyspnea. Other features include tachycardia, tachypnea, crackles in both lung fields, a third heart sound (S3 gallop), oliguria, a thready pulse, hypotension, diaphoresis, cyanosis, and marked anxiety. The patient’s cough may be dry or may produce copious amounts of pink, frothy sputum.

Pulmonary embolism. Acute dyspnea that’s usually accompanied by sudden pleuritic chest pain characterizes pulmonary embolism, a life-threatening disorder. Related findings include tachycardia, a low-grade fever, tachypnea, a nonproductive or productive cough with bloodtinged sputum, a pleural friction rub, crackles, diffuse wheezing, dullness on percussion, decreased breath sounds, diaphoresis, restlessness, and acute anxiety. A massive embolism may cause signs of shock, such as hypotension and cool, clammy skin.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS is an acute infectious disease of unknown etiology; however, a novel Coronavirus has been implicated as a possible cause. Although most cases have been reported in Asia (China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand), cases have been documented in Europe and North America. The incubation period is 2 to 7 days, and the illness generally begins with a fever (usually greater than 100.4°F [38°C]). Other symptoms include a headache, malaise, a dry nonproductive cough, and dyspnea. The severity of the illness is highly variable, ranging from mild illness to pneumonia and, in some cases, progressing to respiratory failure and death.

Shock. Dyspnea arises suddenly and worsens progressively in shock, a life-threatening disorder. Related findings include severe hypotension, tachypnea, tachycardia, decreased peripheral pulses, decreased mental acuity, restlessness, anxiety, and cool, clammy skin.

Tuberculosis. Dyspnea commonly occurs with chest pain, crackles, and a productive cough. Other findings are night sweats, a fever, anorexia and weight loss, vague dyspepsia, palpitations on mild exertion, and dullness on percussion.

Tularemia. Also known as rabbit fever, tularemia causes dyspnea along with a fever, chills, a headache, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Special Considerations

Monitor the dyspneic patient closely. Be as calm and reassuring as possible to reduce his anxiety, and help him into a comfortable position — usually high Fowler’s or the forward-leaning position. Support him with pillows, loosen his clothing, and administer oxygen if appropriate.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as arterial blood gas analysis, chest X-rays, and pulmonary function tests. Administer a bronchodilator, an antiarrhythmic, a diuretic, and an analgesic, as needed, to dilate bronchioles, correct cardiac arrhythmias, promote fluid excretion, and relieve pain.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about pursed-lip and diaphragmatic breathing and chest splinting. Instruct the patient to avoid chemical irritants, pollutants, and people with respiratory infections.

Pediatric Pointers

Normally, an infant’s respirations are abdominal, gradually changing to costal by age 7. Suspect dyspnea in an infant who breathes costally, in an older child who breathes abdominally, or in any child who uses his neck or shoulder muscles to help him breathe.

Acute epiglottiditis and laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) can cause severe dyspnea in a child and may even lead to respiratory or cardiovascular collapse. Expect to administer oxygen, using a hood or cool mist tent.

Geriatric Pointers

Older patients with dyspnea related to chronic illness may not be aware initially of a significant change in their breathing pattern.

REFERENCES

Ditre, J. W. , Gonzalez, B. D., Simmons, V. N. , Faul, L. A., Brandon, T. H., & Jacobson, P. B. (2011). Associations between pain and current smoking status among cancer patients. Pain, 152, 60–65.

Gaguski, M. E., Brandsema, M., Gernalin, L., & Martinez, E. (2010). Assessing dyspnea in patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the acute care setting. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14, 509–513.

Dystonia

Dystonia is marked by slow, involuntary movements of large muscle groups in the limbs, trunk, and neck. This extrapyramidal sign may involve flexion of the foot, hyperextension of the legs, extension and pronation of the arms, arching of the back, and extension and rotation of the neck (spasmodic torticollis). It’s typically aggravated by walking and emotional stress and relieved by sleep. Dystonia may be intermittent — lasting just a few minutes — or continuous and painful. Occasionally, it causes permanent contractures, resulting in a grotesque posture. Although dystonia may be hereditary or idiopathic, it usually results from extrapyramidal disorders or drugs.

History and Physical Examination

If possible, include the patient’s family in the history taking; they may be more aware of behavior

changes than the patient is. Begin by asking them when dystonia occurs. Is it aggravated by emotional upset? Does it disappear during sleep? Is there a family history of dystonia? Obtain a drug history, noting especially if the patient takes a phenothiazine or an antipsychotic. Dystonia is a common adverse effect of these drugs, and the dosage may need to be adjusted to minimize this effect.

Next, examine the patient’s coordination and voluntary muscle movement. Observe his gait as he walks across the room; then, have him squeeze your fingers to assess muscle strength. (See Recognizing dystonia, page 270.) Check coordination by having him touch your fingertip and then his nose repeatedly. Follow this by testing gross motor movement of the leg: Have him place his heel on one knee, slide it down his shin to the top of his great toe, and then, return it to his knee. Finally, assess fine motor movement by asking him to touch each finger to his thumb in succession.

EXAMINATION TIP Recognizing Dystonia

EXAMINATION TIP Recognizing Dystonia

Dystonia, chorea, and athetosis may occur simultaneously. To differentiate between these three, keep these points in mind.

Dystonic movements are slow and twisting and involve large muscle groups in the head, neck (as shown below), trunk, and limbs. They may be intermittent or continuous. Choreiform movements are rapid, highly complex, and jerky.

Athetoid movements are slow, sinuous, and writhing, but always continuous; they typically affect the hands and extremities.

DYSTONIA OF THE NECK (Spasmodic Torticollis)

Medical Causes

Alzheimer’s disease. Dystonia is a late sign of Alzheimer’s disease, which is marked by slowly progressive dementia. The patient typically displays a decreased attention span, amnesia, agitation, an inability to carry out activities of daily living, dysarthria, and emotional lability.

Dystonia musculorum deformans. Prolonged, generalized dystonia is the hallmark of dystonia musculorum deformans, which usually develops in childhood and worsens with age. Initially, it causes foot inversion, which is followed by growth retardation and scoliosis. Late signs include twisted, bizarre postures, limb contractures, and dysarthria.

Hallervorden-Spatz disease. Hallervorden-Spatz disease is a degenerative disease that causes dystonic trunk movements accompanied by choreoathetosis, ataxia, myoclonus, and generalized rigidity. The patient also exhibits a progressive intellectual decline and dysarthria.

Huntington’s disease. Dystonic movements mark the preterminal stage of Huntington’s disease. Characterized by progressive intellectual decline, this disorder leads to dementia and emotional lability. The patient displays choreoathetosis accompanied by dysarthria, dysphagia, facial grimacing, and a wide-based, prancing gait.

Parkinson’s disease. Dystonic spasms are common with Parkinson’s disease. Other classic features include uniform or jerky rigidity, pill-rolling tremor, bradykinesia, dysarthria, dysphagia, drooling, masklike facies, a monotone voice, a stooped posture, and a propulsive gait.

Wilson’s disease. Progressive dystonia and chorea of the arms and legs mark Wilson’s disease. Other common signs and symptoms include hoarseness, bradykinesia, behavior changes, dysphagia, drooling, dysarthria, tremors, and Kayser-Fleischer rings (rusty brown rings at the periphery of the cornea).

Other Causes

Drugs. All three types of phenothiazines can cause dystonia. Piperazine phenothiazines, such as acetophenazine and carphenazine, typically produce this sign; aliphatics, such as chlorpromazine, cause it less commonly; and piperidines rarely cause it.

Haloperidol, loxapine, and other antipsychotics usually produce acute facial dystonia as well as antiemetic doses of metoclopramide, risperidone, metyrosine, and excessive doses of levodopa.

Special Considerations

Encourage the patient to obtain adequate sleep and avoid emotional upset. Avoid range-of-motion exercises, which can aggravate dystonia. If dystonia is severe, protect the patient from injury by raising and padding his bed rails. Provide an uncluttered environment if he’s ambulatory.

Patient Counseling

Educate the patient about dystonia and treatment options. Teach the importance of getting adequate sleep and avoiding emotional upset. Discuss available support groups and services of mental health professionals, if needed.

Pediatric Pointers

Children don’t exhibit dystonia until after they can walk. Even so, it rarely occurs until after age 10. Common causes include Fahr’s syndrome, dystonia musculorum deformans, athetoid cerebral palsy, and the residual effects of anoxia at birth.

REFERENCES

Andrews, C., Aviles-Olmos, I., Hariz, M., & Foltynie, T. (2010). Which patients with dystonia benefit from deep brain stimulation? A metaregression of individual patient outcomes. Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgical Psychiatry, 81, 1383–1389.

Brighina, F., Romano, M., Giglia, G., Saia, V., Puma, A., Giglia, F., … Giglia, F. (2009). Effects of cerebellar TMS on motor cortex of patients with focal dystonia: A preliminary report. Experimental Brain Research, 192, 651–656.

Dysuria

Dysuria — painful or difficult urination — is commonly accompanied by urinary frequency, urgency, or hesitancy. This symptom usually reflects lower urinary tract infection (UTI) — a common disorder, especially in women.

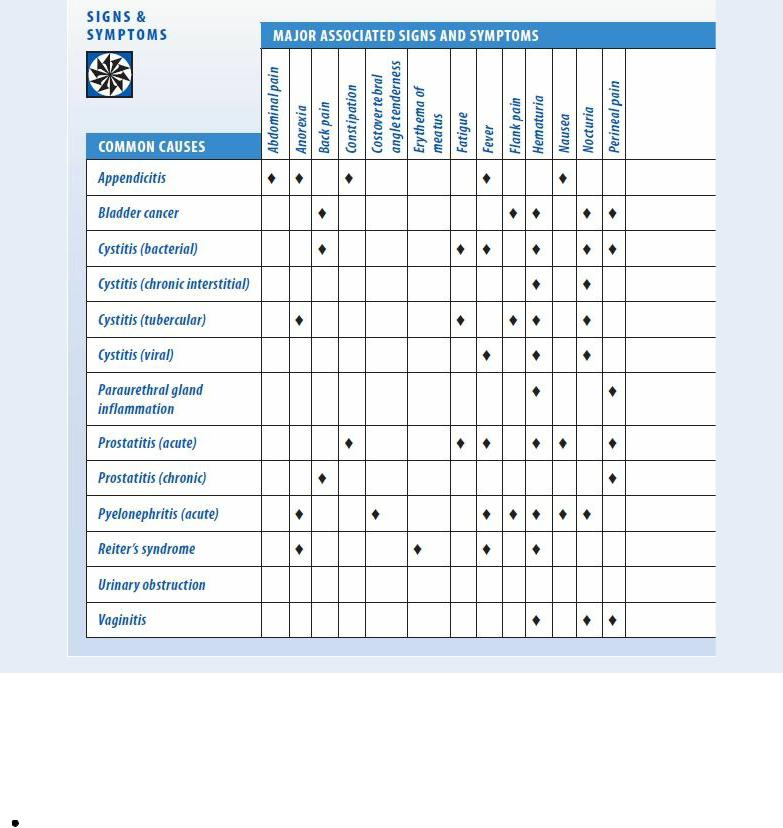

Dysuria results from lower urinary tract irritation or inflammation, which stimulates nerve endings in the bladder and urethra. The onset of pain provides clues to its cause. For example, pain just before voiding usually indicates bladder irritation or distention, whereas pain at the start of urination typically results from bladder outlet irritation. Pain at the end of voiding may signal bladder spasms; in women, it may indicate vaginal candidiasis. (See Dysuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings, Pages 272 and 273.)

History and Physical Examination

If the patient complains of dysuria, have her describe its severity and location. When did she first notice it? Did anything precipitate it? Does anything aggravate or alleviate it?

Next, ask about previous urinary or genital tract infections. Has the patient recently undergone an invasive procedure, such as cystoscopy or urethral dilatation, or had a urinary catheter placed? Also, ask if he has a history of intestinal disease. Ask the female patient about menstrual disorders and the use of products that irritate the urinary tract, such as bubble bath salts, feminine deodorants, contraceptive gels, or perineal lotions. Also ask her about vaginal discharge or pruritus.

Dysuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings

During the physical examination, inspect the urethral meatus for discharge, irritation, or other abnormalities. A pelvic or rectal examination may be necessary.

Medical Causes

Appendicitis. Occasionally, appendicitis causes dysuria that persists throughout voiding and is accompanied by bladder tenderness. Appendicitis is characterized by periumbilical abdominal pain that shifts to McBurney’s point, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation, a slight fever, abdominal rigidity and rebound tenderness, and tachycardia.