Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

History and Physical Examination

If the patient complains of dyspepsia, begin by asking him to describe it in detail. How often and when does it occur, specifically in relation to meals? Do drugs or activities relieve or aggravate it? Has he had nausea, vomiting, melena, hematemesis, a cough, or chest pain? Ask if he’s taking prescription drugs and if he has recently had surgery. Does he have a history of renal, cardiovascular, or pulmonary disease? Has he noticed a change in the amount or color of his urine?

Ask the patient if he’s experiencing an unusual or overwhelming amount of emotional stress. Determine the patient’s coping mechanisms and their effectiveness.

Focus the physical examination on the abdomen. Inspect for distention, ascites, scars, obvious hernias, jaundice, uremic frost, and bruising. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds, and characterize their motility. Palpate and percuss the abdomen, noting tenderness, pain, organ enlargement, or tympany.

Finally, examine other body systems. Ask about behavior changes, and evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness. Auscultate for gallops and crackles. Percuss the lungs to detect consolidation. Note peripheral edema and any swelling of the lymph nodes.

Medical Causes

Cholelithiasis. Dyspepsia may occur with gallstones, usually after eating fatty foods. Biliary colic, a more common symptom of gallstones, causes acute pain that may radiate to the back, shoulders, and chest. The patient may also have diaphoresis, tachycardia, chills, a low-grade fever, petechiae, bleeding tendencies, jaundice with pruritus, dark urine, and clay-colored stools.

Cirrhosis. With cirrhosis, dyspepsia varies in intensity and duration and is relieved by taking an antacid. Other GI effects are anorexia, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal distention, and epigastric or right upper quadrant pain. Weight loss, jaundice, hepatomegaly, ascites, dependent edema, a fever, bleeding tendencies, and muscle weakness are also common. Skin changes include severe pruritus, extreme dryness, easy bruising, and lesions, such as telangiectasis and palmar erythema. Gynecomastia or testicular atrophy may also occur.

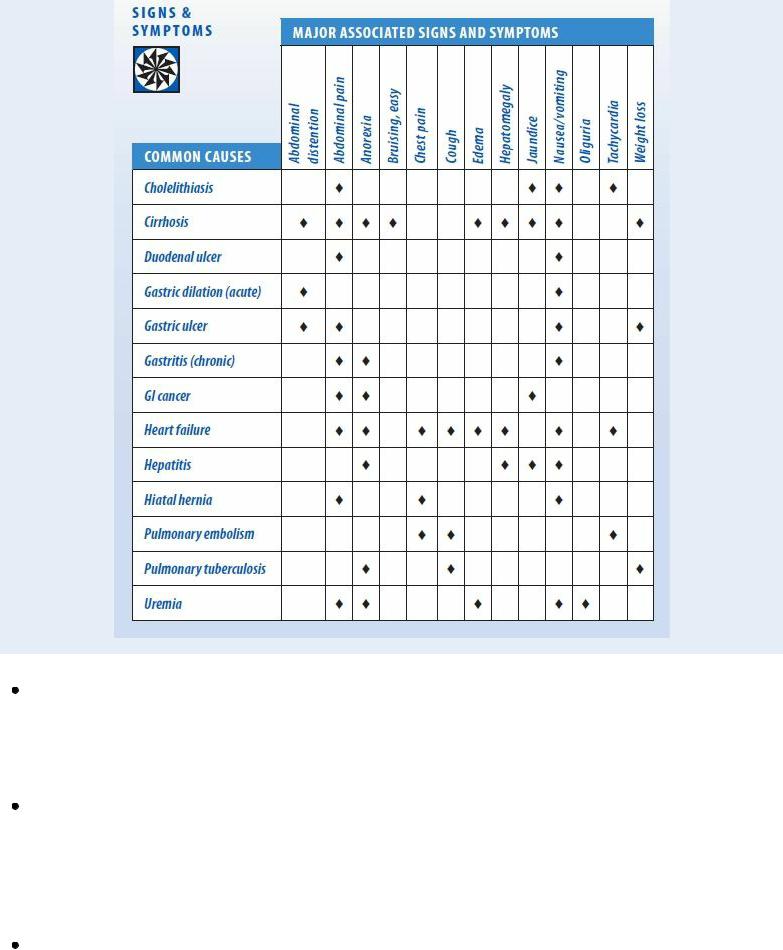

Dyspepsia: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Duodenal ulcer. A primary symptom of a duodenal ulcer, dyspepsia ranges from a vague feeling of fullness or pressure to a boring or aching sensation in the middle or right epigastrium. It usually occurs 1½ to 3 hours after a meal and is relieved by eating food or taking an antacid. The pain may awaken the patient at night with heartburn and fluid regurgitation. Abdominal tenderness and weight gain may occur; vomiting and anorexia are rare.

Gastric dilation (acute). Epigastric fullness is an early symptom of gastric dilation, a lifethreatening disorder. Accompanying dyspepsia are nausea and vomiting, upper abdominal distention, succussion splash, and apathy. The patient may display signs and symptoms of dehydration, such as poor tissue turgor and dry mucous membranes, and of electrolyte imbalance, such as an irregular pulse and muscle weakness. Gastric bleeding may produce hematemesis and melena.

Gastric ulcer. Typically, dyspepsia and heartburn after eating occur early in gastric ulcer. The cardinal symptom, however, is epigastric pain that may occur with vomiting, fullness, and abdominal distention and may not be relieved by eating food. Weight loss and GI bleeding are also characteristics.

Gastritis (chronic). With chronic gastritis, dyspepsia is relieved by antacids; lessened by smaller, more frequent meals; and aggravated by spicy foods or excessive caffeine. It occurs with anorexia, a feeling of fullness, vague epigastric pain, belching, nausea, and vomiting.

GI cancer. GI cancer usually produces chronic dyspepsia. Other features include anorexia, fatigue, jaundice, melena, hematemesis, constipation, and abdominal pain.

Heart failure. Common with right-sided heart failure, transient dyspepsia may occur with chest tightness and a constant ache or sharp pain in the right upper quadrant. Heart failure also typically causes hepatomegaly, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, bloating, ascites, tachycardia, jugular vein distention, tachypnea, dyspnea, and orthopnea. Other findings include dependent edema, anxiety, fatigue, diaphoresis, hypotension, a cough, crackles, ventricular and atrial gallops, nocturia, diastolic hypertension, and cool, pale skin.

Hepatitis. Dyspepsia occurs in two of the three stages of hepatitis. The preicteric phase produces moderate to severe dyspepsia, a fever, malaise, arthralgia, coryza, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, an altered sense of taste or smell, and hepatomegaly. Jaundice marks the onset of the icteric phase, along with continued dyspepsia and anorexia, irritability, and severe pruritus. As jaundice clears, dyspepsia and other GI effects also diminish. In the recovery phase, only fatigue remains.

Hiatal hernia. Dyspepsia is a result of the lower portion of the esophagus and the upper portion of the stomach rising into the chest when abdominal pressure increases.

Pulmonary embolism. Sudden dyspnea characterizes pulmonary embolism, a potentially fatal disorder; however, dyspepsia may occur as an oppressive, severe, substernal discomfort. Other findings include anxiety, tachycardia, tachypnea, a cough, pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, syncope, cyanosis, jugular vein distention, and hypotension.

Pulmonary tuberculosis. Vague dyspepsia may occur along with anorexia, malaise, and weight loss. Common associated findings include a high fever, night sweats, palpitations on mild exertion, a productive cough, dyspnea, adenopathy, and occasional hemoptysis.

Uremia. Of the many GI complaints associated with uremia, dyspepsia may be the earliest and most important. Others include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, bloating, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, epigastric pain, and weight gain. As the renal system deteriorates, the patient may experience edema, pruritus, pallor, hyperpigmentation, uremic frost, ecchymoses, sexual dysfunction, poor memory, irritability, a headache, drowsiness, muscle twitching, seizures, and oliguria.

Other Causes

Drugs. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially aspirin, commonly cause dyspepsia. Diuretics, antibiotics, antihypertensives, corticosteroids, and many other drugs can cause dyspepsia, depending on the patient’s tolerance of the dosage.

Surgery. After GI or other surgery, postoperative gastritis can cause dyspepsia, which usually disappears in a few weeks.

Special Considerations

Changing the patient’s position usually doesn’t relieve dyspepsia, but providing food or an antacid may. Have food available at all times, and give an antacid 30 minutes before a meal or 1 hour after it.

Because various drugs can cause dyspepsia, give these after meals, if possible.

Classifying Dysphagia

Because swallowing occurs in three distinct phases, dysphagia can be classified by the phase that it affects. Each phase suggests a specific pathology for dysphagia.

PHASE 1

Swallowing begins in the transfer phase with chewing and moistening of food with saliva. The tongue presses against the hard palate to transfer the chewed food to the back of the throat; cranial nerve V then stimulates the swallowing reflex. Phase 1 dysphagia typically results from a neuromuscular disorder.

PHASE 2

In the transport phase, the soft palate closes against the pharyngeal wall to prevent nasal regurgitation. At the same time, the larynx rises and the vocal cords close to keep food out of the lungs; breathing stops momentarily as the throat muscles constrict to move food into the esophagus. Phase 2 dysphagia usually indicates spasm or cancer.

PHASE 3

Peristalsis and gravity work together in the entrance phase to move food through the esophageal sphincter and into the stomach. Phase 3 dysphagia results from lower esophageal narrowing by diverticula, esophagitis, and other disorders.

Provide a calm environment to reduce stress, and make sure that the patient gets plenty of rest. Discuss other ways to deal with stress, such as deep breathing and guided imagery. In addition, prepare the patient for endoscopy to evaluate the cause of dyspepsia.

Patient Counseling

Discuss the importance of small, frequent meals. Describe foods or fluids the patient should avoid. Discuss stress reduction techniques the patient can use.

Pediatric Pointers

Dyspepsia may occur in adolescents with peptic ulcer disease, but it isn’t relieved by food. It may also occur in congenital pyloric stenosis, but projectile vomiting after meals is a more characteristic sign. It may also result from lactose intolerance.

Geriatric Pointers

Most older patients with chronic pancreatitis experience less severe pain than younger adults; some have no pain at all.

REFERENCES

Aro, P. , Talley, N. J. , Ronkainen, J, Storskrubb, T. , Vieth, M. , Johansson, S. E., … Agréus, L. (2009) . Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology, 137, 94–100.

Lehoux, C. P. , & Abbott, F. V. (2011). Pain, sensory function, and neurogenic inflammatory response in young women with low mood.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70, 241–249.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia — difficulty swallowing — is a common symptom that’s usually easy to localize. It may be constant or intermittent and is classified by the phase of swallowing it affects. (See Classifying Dysphagia.) Among the factors that interfere with swallowing are severe pain, obstruction, abnormal peristalsis, an impaired gag reflex, and excessive, scanty, or thick oral secretions.

Dysphagia is the most common — and sometimes the only — symptom of esophageal disorders. However, it may also result from oropharyngeal, respiratory, neurologic, and collagen disorders or from the effects of toxins and treatments. Dysphagia increases the risk of choking and aspiration and may lead to malnutrition and dehydration.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient suddenly complains of dysphagia and displays signs of respiratory distress, such as dyspnea and stridor, suspect an airway obstruction and quickly perform abdominal thrusts. Prepare to administer oxygen by mask or nasal cannula or to assist with endotracheal intubation.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s dysphagia doesn’t suggest an airway obstruction, begin a health history. Ask the patient if swallowing is painful. If so, is the pain constant or intermittent? Have the patient point to where dysphagia feels most intense. Does eating alleviate or aggravate the symptom? Are solids or liquids more difficult to swallow? If the answer is liquids, ask if hot, cold, and lukewarm fluids affect him differently. Does the symptom disappear after he tries to swallow a few times? Is swallowing easier if he changes position? Ask if he has recently experienced vomiting, regurgitation, weight loss, anorexia, hoarseness, dyspnea, or a cough.

To evaluate the patient’s swallowing reflex, place your finger along his thyroid notch and instruct him to swallow. If you feel his larynx rise, the reflex is intact. Next, have him cough to assess his cough reflex. Check his gag reflex if you’re sure he has a good swallow or cough reflex. Listen closely to his speech for signs of muscle weakness. Does he have aphasia or dysarthria? Is his voice nasal, hoarse, or breathy? Assess the patient’s mouth carefully. Check for dry mucous membranes and thick, sticky secretions. Observe for tongue and facial weakness and obvious obstructions (for example, enlarged tonsils). Assess the patient for disorientation, which may make him neglect to swallow.

Medical Causes

Achalasia. Most common in patients ages 20 to 40, achalasia produces phase 3 dysphagia for solids and liquids. The dysphagia develops gradually and may be precipitated or exacerbated by stress. Occasionally, it’s preceded by esophageal colic. Regurgitation of undigested food, especially at night, may cause wheezing, coughing, or choking as well as halitosis. Weight loss, cachexia, hematemesis and, possibly, heartburn are late findings.

Airway obstruction. Life-threatening upper airway obstruction is marked by signs of respiratory distress, such as crowing and stridor. Phase 2 dysphagia occurs with gagging and dysphonia. When hemorrhage obstructs the trachea, dysphagia is usually painless and rapid in onset. When inflammation causes the obstruction, dysphagia may be painful and develop slowly.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Besides dysphagia, ALS causes muscle weakness and atrophy, fasciculations, dysarthria, dyspnea, shallow respirations, tachypnea, slurred speech, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), and emotional lability.

Bulbar paralysis. Phase 1 dysphagia occurs along with drooling, difficulty chewing, dysarthria, and nasal regurgitation. Dysphagia for solids and liquids is painful and progressive. Accompanying features may include arm and leg spasticity, hyperreflexia, and emotional lability.

Esophageal cancer. Phases 2 and 3 dysphagia is the earliest and most common symptom of esophageal cancer. Typically, this painless, progressive symptom is accompanied by rapid weight loss. As the cancer advances, dysphagia becomes painful and constant. In addition, the patient complains of steady chest pain, a cough with hemoptysis, hoarseness, and a sore throat. He may also develop nausea and vomiting, a fever, hiccups, hematemesis, melena, and halitosis. Esophageal compression (external). Usually caused by a dilated carotid or aortic aneurysm, esophageal compression — a rare condition — causes phase 3 dysphagia as the primary symptom. Other features depend on the cause of the compression.

Esophageal diverticulum. Esophageal diverticulum causes phase 3 dysphagia when the

enlarged diverticulum obstructs the esophagus. Associated signs and symptoms include food regurgitation, a chronic cough, hoarseness, chest pain, and halitosis.

Esophageal obstruction by foreign body. Sudden onset of phase 2 or 3 dysphagia, gagging, coughing, and esophageal pain characterize this potentially life-threatening condition. Dyspnea may occur if the obstruction compresses the trachea.

Esophageal spasm. The most striking symptoms of esophageal spasm are phase 2 dysphagia for solids and liquids and a dull or squeezing substernal chest pain. The pain may last up to an hour and may radiate to the neck, arm, back, or jaw; however, it may be relieved by drinking a glass of water. Bradycardia may also occur.

Esophageal stricture. Usually caused by a chemical ingestion or scar tissue, esophageal stricture causes phase 3 dysphagia. Drooling, tachypnea, and gagging may also be evident. Esophagitis. Corrosive esophagitis, resulting from ingestion of alkali or acids, causes severe phase 3 dysphagia. Accompanying it are marked salivation, hematemesis, tachypnea, a fever, and intense pain in the mouth and anterior chest that’s aggravated by swallowing. Signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia, may also occur.

Candidal esophagitis causes phase 2 dysphagia, a sore throat and, possibly, retrosternal pain on swallowing. With reflux esophagitis, phase 3 dysphagia is a late symptom that usually accompanies stricture development. The patient complains of heartburn, which is aggravated by strenuous exercise, bending over, or lying down and is relieved by sitting up or taking an antacid.

Other features include regurgitation; frequent, effortless vomiting; a dry, nocturnal cough; and substernal chest pain that may mimic angina pectoris. If the esophagus ulcerates, signs of bleeding, such as melena and hematemesis, may occur along with weakness and fatigue.

Gastric carcinoma. Infiltration of the cardia or esophagus by gastric carcinoma causes phase 3 dysphagia along with nausea, vomiting, and pain that may radiate to the neck, back, or retrosternum. In addition, perforation causes massive bleeding with coffee-ground vomitus or melena.

Laryngeal cancer (extrinsic). Phase 2 dysphagia and dyspnea develop late in laryngeal cancer. Accompanying features include a muffled voice, stridor, pain, halitosis, weight loss, ipsilateral otalgia, a chronic cough, and cachexia. Palpation reveals enlarged cervical nodes.

Lead poisoning. Painless, progressive dysphagia may result from lead poisoning. Related findings include a lead line on the gums, a metallic taste, papilledema, ocular palsy, footdrop or wristdrop, and signs of hemolytic anemia, such as abdominal pain and a fever. The patient may be depressed and display severe mental impairment and seizures.

Myasthenia gravis. Fatigue and progressive muscle weakness characterize myasthenia gravis and account for painless phase 1 dysphagia and possibly choking. Typically, dysphagia follows ptosis and diplopia. Other features include masklike facies, a nasal voice, frequent nasal regurgitation, and head bobbing. Shallow respirations and dyspnea may occur with respiratory muscle weakness. Signs and symptoms worsen during menses and with exposure to stress, cold, or infection.

Oral cavity tumor. Painful phase 1 dysphagia develops along with hoarseness and ulcerating lesions.

Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia is a common symptom with Parkinson’s disease. Other findings include masklike facies, drooling, muscle rigidity, difficulty walking, muscle weakness, and a stooped posture.

Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Plummer-Vinson syndrome causes phase 3 dysphagia for solids in some women with severe iron deficiency anemia. Related features include upper esophageal pain; atrophy of the oral or pharyngeal mucous membranes; tooth loss; a smooth, red, sore tongue; a dry mouth; chills; inflamed lips; spoon-shaped nails; pallor; and splenomegaly.

Rabies. Severe phase 2 dysphagia for liquids results from painful pharyngeal muscle spasms occurring late in this rare, life-threatening disorder. In fact, the patient may become dehydrated and possibly apneic. Dysphagia also causes drooling, and in 50% of cases, it’s responsible for hydrophobia. Eventually, rabies causes progressive flaccid paralysis that leads to peripheral vascular collapse, coma, and death.

Stroke (brain stem). A brain stem stroke is characterized by bulbar palsy resulting in the triad of dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia. The sudden development of any one or more of the following symptoms can indicate a stroke: dysphagia, hemiparesis, spasticity, drooling, numbness, tingling, decreased sensation, or vision changes.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE may cause progressive phase 2 dysphagia. However, its primary signs and symptoms include nondeforming arthritis, a characteristic butterfly rash, and photosensitivity.

Tetanus. Phase 1 dysphagia usually develops about 1 week after the patient receives a puncture wound. Other characteristics include marked muscle hypertonicity, hyperactive DTRs, tachycardia, diaphoresis, drooling, and a low-grade fever. Painful, involuntary muscle spasms account for lockjaw (trismus), risus sardonicus, opisthotonos, boardlike abdominal rigidity, and intermittent tonic seizures.

Other Causes

Procedures. Recent tracheostomy or repeated or prolonged intubation may cause temporary dysphagia.

Radiation therapy. When directed against oral cancer, this therapy may cause scant salivation and temporary dysphagia.

Special Considerations

Stimulate salivation by talking with the patient about food, adding a lemon slice or dill pickle to his tray, and providing mouth care before and after meals. Moisten his food with a little liquid if the patient has decreased salivation. Administer an anticholinergic or antiemetic to control excess salivation. If he has a weak or absent cough reflex, begin tube feedings or esophageal drips of special formulas.

Consult with the dietitian to select foods with distinct temperatures and textures. The patient should avoid sticky foods, such as bananas and peanut butter. If he has mucus production, he should avoid uncooked milk products. Consult a therapist to assess the patient for his aspiration risk and for swallowing exercises to possibly help decrease his risk. At mealtimes, take measures to minimize the risk of choking and aspiration. Place the patient in an upright position, and have him flex his neck forward slightly and keep his chin at midline. Instruct him to swallow multiple times before taking the next bite or sip. Separate solids from liquids, which are harder to swallow.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic evaluation, including endoscopy, esophageal manometry, esophagography, and the esophageal acidity test, to pinpoint the cause of dysphagia.

Patient Counseling

Discuss easy-to-swallow foods. Explain measures the patient can take to reduce the risk of choking and aspiration.

Pediatric Pointers

In looking for dysphagia in an infant or a small child, be sure to pay close attention to his sucking and swallowing ability. Coughing, choking, or regurgitation during feeding suggests dysphagia.

Corrosive esophagitis and esophageal obstruction by a foreign body are more common causes of dysphagia in children than in adults. However, dysphagia may also result from congenital anomalies, such as annular stenosis, dysphagia lusoria, esophageal atresia, and cleft palate.

Geriatric Pointers

In patients older than age 50, dysphagia is commonly the presenting complaint in cases of head or neck cancer. The incidence of such cancers increases markedly in this age group.

REFERENCES

Rihn, J. A., Kane, J., Albert, T. J., Vaccaro, A. R. , & Hilibrand, A. S. (2011). What is the incidence and severity of dysphagia after anterior cervical surgery? Clinical Orthopedic Related Research, 469, 658–665.

Siska, P.A. , Ponnappan, R.K., Hohl, J.B., Lee, J. Y. , Kang, J. D., & Donaldson, W. F., III . (2011). Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: A prospective study using the swallowing-quality of life questionnaire and analysis of patient comorbidities . Spine, 36, 1387–1391.

Dyspnea

Typically a symptom of cardiopulmonary dysfunction, dyspnea is the sensation of difficult or uncomfortable breathing. It’s usually reported as shortness of breath. Its severity varies greatly and is usually unrelated to the severity of the underlying cause. Dyspnea may arise suddenly or slowly and may subside rapidly or persist for years.

Most people normally experience dyspnea when they exert themselves, and its severity depends on their physical condition. In a healthy person, dyspnea is quickly relieved by rest. Pathologic causes of dyspnea include pulmonary, cardiac, neuromuscular, and allergic disorders. It may also be caused by anxiety. (See Dyspnea: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 264 and 265.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If a patient complains of shortness of breath, quickly look for signs of respiratory distress, such as tachypnea, cyanosis, restlessness, and accessory muscle use. Prepare to administer oxygen by nasal cannula, mask, or endotracheal tube. Ensure patent I.V. access, and begin cardiac monitoring and oxygen saturation monitoring to detect arrhythmias and low oxygen saturation, respectively. Expect to insert a chest tube for severe pneumothorax and to administer continuous positive airway pressure or apply rotating tourniquets for pulmonary edema.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient can answer questions without increasing his distress, take a complete history. Ask if the shortness of breath began suddenly or gradually. Is it constant or intermittent? Does it occur during activity or while at rest? If the patient has had dyspneic attacks before, ask if they’re increasing in severity. Can he identify what aggravates or alleviates these attacks? Does he have a productive or nonproductive cough or chest pain? Ask about recent trauma, and note a history of upper respiratory tract infection, deep vein phlebitis, or other disorders. Ask the patient if he smokes or is exposed to toxic fumes or irritants on the job. Find out if he also has orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or progressive fatigue.

Dyspnea: Common Causes and Associated Findings