Body & Society-2005-Crossley-1-35

.pdf

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques:

On Body Modification and

Maintenance

NICK CROSSLEY

Much work in the sociology of the body has been devoted to an analysis of body modification and maintenance; that is, to practices such as diet, exercise, bodybuilding, tattooing, piercing, dress and cosmetic surgery (e.g. Crossley, 2004a, 2004b; DeMello, 2000; Entwistle, 2000; Featherstone, 1982, 2000; Gurney, 2000; Monaghan, 2001; Pitts, 1998, 2003; Rosenblatt, 1997; Sanders, 1988; Sassatelli, 1999a, 1999b; Smith, 2001; Sweetman, 1999; Turner, 1999). In this paper I seek to contribute to this work on two fronts. First, developing a theme already present in the literature, I explore the reflexive and embodied nature of practices of modification/maintenance. It is very easy when discussing this topic to slip into a dualistic framework, opposing the body to either self or society and seeming to suggest that the former is transformed by the latter. We talk, for example, about ‘my body’, what ‘I’ think of ‘it’, what ‘I’ put ‘it’ through and what ‘I’ want ‘it’ to look like. On one level this linguistic habit resonates with our experience. Our socially instituted capacity for reflexivity allows us to turn back upon and objectify ourselves, effecting a distinction between what Mead (1967) referred to as the ‘I’ and the ‘me’; the body as subject and the body as object. On this level

Body & Society © 2005 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi), Vol. 11(1): 1–35

DOI: 10.1177/1357034X05049848

www.sagepublications.com

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

2 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

we both are our bodies and we have a body (Crossley, 2001). However, it is necessary to recognize this split as reflexive rather than substantial in nature. It derives from our acquired capacity to assume the role of another and thereby to achieve an outside perspective on ourselves, a process which generates a sense of our being distinct from the qualities we identify with our self when assuming this ‘other’ role. It does not indicate a substantial distinction between mind/self and body. It does not often even reflect the emergent stratification between the body as a biochemical structure and the body as a sensuous, active agent. ‘My body’, the body I ‘have’, is a moral, aesthetic, acting and sensuous being. I worry as much about its appearance, performances and transgressions as I do about its biological structure. The best work in the sociology of the body recognizes this. It challenges dualism, insisting that ‘I’ am ‘my body’ and that body projects are therefore reflexive projects (see esp. Crossley, 2001, 2004a; Entwistle, 2000; Monaghan, 1999; Smith, 2001; Sweetman, 1999; Wacquant, 1995, 2004).

In this article I advance this idea through an exploration of what I call reflexive body techniques (RBTs), a concept which builds upon Marcel Mauss’s (1979) concept of body techniques (see also Crossley, 1995, 2004a, 2004c) and upon my own earlier work on reflexive embodiment (Crossley, 2001). The concept of RBTs, I will show, affords a powerful analytic purchase upon the embodied and reflexive processes and practices involved in projects of body modification/maintenance and, indeed, upon the reflexive separation of the embodied I and me.

The concept of RBTs also frames my second theme: the social distribution and diffusion of practices of modification. Specifically, I will demonstrate and seek to explain the fact that the overall repertoire of RBTs belonging to any group can always be differentiated into: (i) clusters which all members practise, (ii) clusters which the majority or a large minority practise and (iii) clusters which only a small minority practise. Furthermore, I will demonstrate and seek to explain the fact that within the ‘zone’ of less widely practised RBTs we find clusters which ‘go together’ thematically and/or in the sense of being statistically associated. Recognizing this pattern of distribution is important because it alerts us both to the different meanings attaching to specific clusters and to their variable conditions of diffusion and appropriation; their levels of accessibility and the different balance of costs and rewards that attach to them.

This is an important observation in relationship to our broader focus. General descriptions such as ‘body modification’ and ‘body maintenance’ can be misleading because they imply that we are dealing with a set of practices with a common identity, purpose, accessibility, etc. They fail to distinguish between the social logic of distinct sets of practices. This can lead to theoretical accounts which do likewise. Giddens’ (1991) theory of ‘the body in late modernity’, to take one

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 3

example, offers a single explanation of practices of body maintenance, based around the need for social agents to construct coherent self-narratives in an increasingly detraditionalized and risk-aware environment. This is arguably a good account in relationship to some practices of modification, perhaps diet and exercise (although see Crossley, 2004b). But it is far from obvious that it explains all modification practices. We are forced to ask whether other practices, including both more mundane and widespread practices, such as tooth-brushing and washing, and also more marginal practices, such as scarification and multiple piercing, can be explained in the same way. And even if they can we must question whether the difference in rates of uptake between such practices can be ignored, as it is by those who theorize body modification at a very high level of abstraction and generalization, in a largely undifferentiated fashion. The fact that some practices achieve an almost 100 percent rate of uptake in our society, whilst others are practised by less than 1 percent of the population, and others still by 30 percent, 40 percent or 50 percent is and should be question begging for sociologists of the body, as indeed should the clustering and association of specific techniques. They suggest the presence of a social dynamic we have not yet recognized or analysed.

There are, of course, many focused empirical studies which explore in detail the specificities of particular practices, such as bodybuilding, piercing or cosmetic surgery (Davis, 1995; DeMello, 2000; Irwin, 2001; Klein, 1993; Klesse, 1999; Kosut, 2000; Monaghan, 1999, 2001; Myers, 1992; Pitts, 1998; Rosenblatt, 1997; Sanders, 1988; St Martin and Gavey, 1996; Sweetman, 1999; Turner, 1999; Vail, 1999). These are an important antidote to overgeneralized theories and they shed light upon individual practices. However, their specificity denies us the possibility of a broader, comparative grasp of the spectrum of practices to be found in contemporary societies. What is needed, to complement these studies, and what I hope to move towards in this article, is a broad and differentiated framework for thinking about body modification/maintenance in general; a framework that can draw a diverse range of practices together, while remaining sensitive to their particularities. The article will not take us all of the way to this goal but I hope at least to take a few important steps in that direction.

A thorough analysis of patterns of differentiation, at least insofar as it includes consideration of different rates of uptake, requires that we integrate the qualitative methods and theoretical investigations common in the sociology of the body with certain more quantitative techniques, designed specifically to enable exploration of distributions, associations, clustering, etc. Any of a range of such techniques might be used, from quite basic frequency distributions through to more complex statistical techniques. In this article, alongside frequency

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

4 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

distributions and cross-tabulation, I will use ‘multi-dimensional scaling’ (MDS), a technique which allows us to visualize, in the form of scatterplots or ‘perceptual maps’, the statistical associations between large numbers of categorical variables (Canter, 1985; Kruskal and Wish, 1978). On an MDS plot we can see which RBTs ‘go together’, in the sense that practice of one is associated with practice of the other(s), because they form visible clusters. These statistical associations and clusters often reflect thematic clustering. RBTs are statistically associated because they belong to a common lifestyle, habitus or self-narrative. Their association at the level of meaning increases the probability that agents drawn to one will be drawn to the other(s), which in turn generates a statistical association between them.

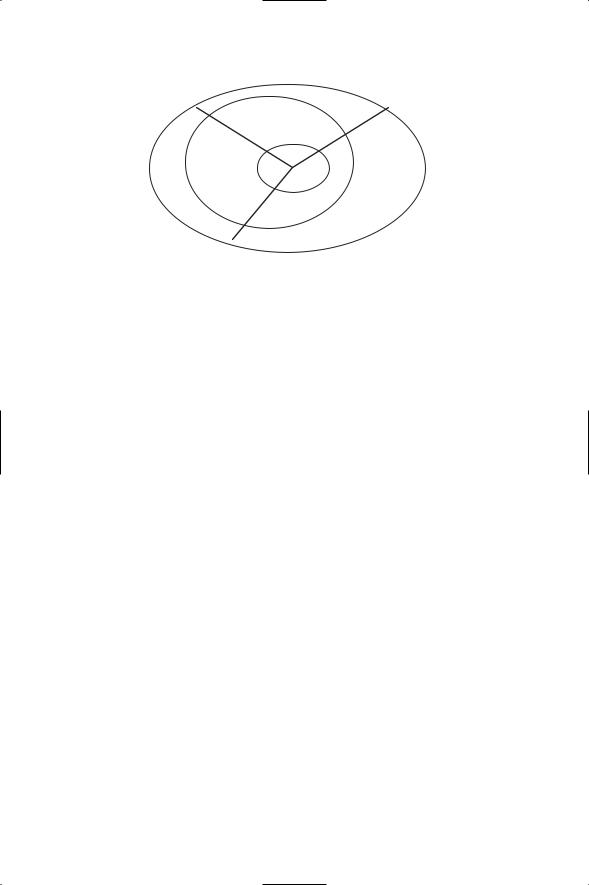

Moreover, under certain conditions an MDS plot allows us, simultaneously, to map frequency distributions. One example of this is a pattern of distribution/interpretation, which I return to later, known as the radex (Canter, 1985). In a radex, variables (e.g. body techniques) which occur most frequently in a population cluster towards the centre of the plot, or towards a point that we can treat as the centre. Most people do most of them and this causes them to congeal centrally on the plot. Less frequently occurring variables spread progressively outwards from this centre, with the least frequent appearing at the extremes of the plot. In our attempt to interpret such plots we can represent these frequency patterns by drawing concentric circles onto the plot which locate specific sets of variables in different frequency ‘zones’. In addition, however, as we move out from our innermost circle, we find that the less frequently occurring variables form distinct clusters in accordance with the other variables that they are positively and negatively associated with – and with which, as noted above, they may also therefore be thematically associated. This allows us to further subdivide our plot. We can mark out clusters at the ‘margins’ of our plot by way of segments. In Figure 1, for example, three concentric circles demarcate frequency zones into which hypothetical variables (represented by letters) fall. A and J are variables which occur most frequently (e.g. they might be very commonly practised body techniques). F, T, G, P and Q are variables which occur less frequently. And D, I and N are variables which occur relatively rarely (they might be techniques which very few people practise). In addition to mapping frequencies, however, the plot allows us to map out thematic clusters. We can divide our map into interpretable segments. We might seek to interpret the clustering D, T and G, for example, as evidence of their belonging to a common habitus or, following Giddens (1991), a specific narrative trajectory (A is too commonly practised to count). Perhaps they are all techniques which embody values of ‘health and fitness’, while P, Q and N

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 5

F I

T A J

D G N

P Q

Figure 1 A Radex

belong to a ‘modern primitivist’ habitus. How we divide the plot, where we draw our lines, will reflect our own theoretical judgements. We might wish to use theoretical understandings to formulate hypotheses regarding clustering prior to our mapping exercise or may simply use theory for retrospective interpretation. In either case, however, maps require theoretically based interpretation if they are to have any sense. We try to match clusters with theoretical accounts – always expecting that some anomalies will be thrown up along the way. What prevents this from being an interpretative ‘free for all’ is the underlying structure of the map we are working with – which is largely given by virtue of MDS technique.1 We have considerable room for manoeuvre when we slice the map up, but we are always restrained by the relative positioning of the variables (and our understanding of the technique that has produced it). We cannot pretend that two variables are close if they are not.

Aims, Method and Data

I begin the main body of the article by outlining the concept of RBTs, discussing certain thorny issues that attach to it, such as the problem posed by the idea of purpose, and elaborating its relationship to human selfhood. Having established the concept in this way, I then reflect upon the distribution of RBTs within the population, returning to the radex concept outlined above, showing how it relates to reflexive body techniques and positing a preliminary account for explaining the social distribution of RBTs. Before doing any of this, however, it is necessary to spell out the four primary aims of the article in a little more detail.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

6 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

First, I aim to advance our substantive understanding of practices of body modification/maintenance by formulating an approach, centred upon RBTs and their distribution, which allows us to deal with a broad range of practices, in a non-dualistic way, without subsuming them into an over-general theoretical account. Second, following Williams and Bendelow’s criticism that ‘Discourses on . . . the “reflexive” body continue to be pitched, for the most part, at the level of broad claims and sweeping generalisations with little concern for empirical detail’ (1998: 104), I aim to demonstrate a way in which the analysis of body modification/maintenance can be made more empirical. Moreover, it is my contention that the framework I posit, centred upon RBTs, lends itself equally to qualitative and quantitative forms of investigation. Indeed it demands both. The present article leans in the quantitative direction, but it flags up qualitative issues and I have researched RBTs in a more ethnographic and phenomenological way elsewhere (Crossley, 2004a). Third, I aim to advance both my own earlier attempts to build upon Mauss’s (1979) concept of ‘body techniques’, a concept which I believe to be crucial for the sociology of the body (see also Crossley, 1995, 2004a, 2004c) and my own earlier theorization of reflexive embodiment (Crossley, 2001). Finally, I aim by way of a discussion of statistical methods that have been little used in sociology, to explore a potential methodological innovation for the study of the body, and particularly for the analysis of body techniques.

To allow me to demonstrate this more fully I have conducted a small questionnaire survey (n = 304), focused upon the distribution and diffusion of a number of RBTs and ‘ensembles’ (defined below). The questions used in the survey were drawn from a consultation and piloting exercise, and also a media search. These preliminary investigations allowed me to build a rough picture of the current societal repertoire of RBTs and their ensembles. In the questionnaire itself respondents were asked to indicate whether they had engaged in any of these techniques within a given time-frame, which varied according to the practice. In some cases further elaboration was asked for (e.g. What sort of exercise? How many hours? How many tattoos? Where on your body?). A number of questions concerning consultation of body-related2 web-sites, magazines and magazine/newspaper articles – all potential sources of information on RBTs – were also included. Finally, I included a few basic demographic questions.

Sampling for the survey was opportunistic and snowballed. I approached friends, family, colleagues and students, asking them both to fill in the questionnaire and to distribute it within their own personal networks. The resulting sample was relatively balanced with respect to gender – though with slightly

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 7

more females3 – and involved representation from a variety of age,4 social class,5 ethnic6 and religious7 groups. I make no claim with respect to representativeness, however. The sample was convenient and sufficient for my present, preliminary investigations, but it is far from perfect. Nor do I suggest that the survey results are particularly startling. I found what I expected to find. The point of the survey, however, was to allow me to check that my assumptions were borne out amongst a population whom I have no reason to believe are unusual,8 to consider how we might move from assumptions to empirically verifiable models, and also to explore the above-mentioned methodological innovations.

With this said, we can turn to the main arguments of the article. I begin with a discussion of Mauss’s formulation of ‘body techniques’. My claim, to reiterate, is that we can conceptualize and analyse practices of body modification/maintenance as particular types of body technique, namely reflexive body techniques, and that there are advantages to doing so.

Body Techniques

Mauss (1979) arrived at the concept of body techniques after having observed both that certain embodied practices (e.g. spitting, hunting techniques and eating with a knife and fork) are specific to particular societies, and that others vary considerably in style across societies and social groups. Women walk differently to men, the bourgeoisie talk differently to the proletariat, the French military march and dig differently to British troops and so on. Building on these observations, he defines body techniques as ‘ways in which from society to society men [sic] know how to use their bodies’ (1979: 97). This definition is potentially problematic as it can seem to suggest, in the fashion warned against above, that ‘men’ and ‘their bodies’ are different things. Given the way in which Mauss pursues his point, however, it is reasonable to assume that this is not his intention. Indeed, the concept is used to effect a sophisticated, albeit often tacit innovation in non-dualistic sociology. Mauss’s description of body techniques as ‘habitus’ is an important point of entry for grasping this innovation. ‘Habitus’, he explains, is a Latin rendering of the Greek ‘hexis’ (or ‘exis’), a concept which is central to Aristotle’s philosophy, wherein it denotes acquired and embodied dispositions9 which constitute forms of practical reason or wisdom (see Aristotle, 1955). Habitus and thus body techniques have a double edge in this definition. They are forms of embodied, pre-reflective understanding, knowledge or reason. And they are social. They emerge and spread within a collective context, as the result of interaction, such that they can be identified with specific social groups or networks:

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

8 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

. . . I have had this notion of the social nature of ‘the habitus’ for many years. Please note that I use the Latin word – it should be understood in France – habitus. The word translates infinitely better than ‘habitude’ (habit or custom), the ‘exis’, the ‘acquired ability’ and ‘faculty’ of Aristotle (who was a psychologist). It does not designate those metaphysical habitudes, that mysterious ‘memory’, the subject of volumes or short and famous theses. These ‘habits’ do not vary just with individuals and their imitations; they vary between societies, educations, proprieties and fashions, prestiges. In them we should see the techniques and work of collective and individual practical reason rather than, in the ordinary way, merely the soul and its repetitive faculties. (Mauss, 1979: 101)

I will return to the question of how body techniques distinguish and differentiate social groups later. Here I am interested in the manner in which the concept simultaneously holds together social, corporeal and cognitive elements. In doing this ‘body techniques’ rejoins the Durkheimian tradition it derives from in two respects. First, it rejoins the concept of ‘social facts’, integrating it with a consideration of biological and psychological facts (see also Lévi-Strauss, 1987). Body techniques are social facts. They vary across societies and social groups. They pre-exist and will outlive the specific individuals who practise them at any point in time. Mauss even seeks to show – albeit somewhat problematically (Crossley, 1995, 2004a) – how they ‘constrain’ agents. At the same time, however, they presuppose biological structures and embody knowledge, reason and psychological properties. Styles of walking vary across social groups, for example, indicating a social basis, but all of these different styles presuppose bipedalism, not to mention the plasticity and intelligence that allow the organism to develop and learn different ways of walking. They thus have biological preconditions. Furthermore, styles of walking embody understanding and knowledge. Switching to ‘tiptoes’ when silence is required, for example, indicates a grasp of the conditions most conducive to minimizing noise, while walking a tightrope, and indeed walking per se, requires a practical grasp of principles of balance, force, etc. When we adjust our posture to steady ourselves we engage in practical physics. Finally, certain styles of walking, such as a proud march or arrogant strut, embody an emotional intention (in the phenomenological sense of ‘intention’) and may even be employed as a means of generating such an intention (see Crossley, 2004c). As both Sartre (1993) and Merleau-Ponty (1962) note, we can generate emotional intentions, putting ourselves into particular moods, by acting out the mood; that is, by performing the body techniques (partly) constitutive of it. This is a key function of body techniques within certain rituals (Crossley, 2004c). Thus, body techniques have a psychological dimension too.

Second, ‘body techniques’ extends the Durkheimian notion of collective representations, a notion that Mauss himself developed with Durkheim (Durkheim and Mauss, 1963). It identifies collective forms of wisdom and

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 9

reasoning which are pre-representational in form; that is, forms of pre-reflective knowledge (know-how) and understanding that consist entirely in a capacity to do certain sorts of things. The movements of the body, for Mauss, are not, as they were for the behaviourists and other writers of his time, mere movements. They are practical and embodied forms of knowledge and understanding. Importantly, this does not mean that movement is guided by knowledge but rather that certain forms of knowledge and understanding are inseparable from and consist entirely in particular forms of acquired, embodied competence. By the same token this means that certain forms of knowledge and understanding are inseparable from the capacity to do certain sorts of things, irrespective of whether representations or propositions are involved. Body techniques are ‘collective pre-representations’

– though, as we will see shortly, not everyone in the collective has equal access to them.

The ‘mindful’ aspect of body techniques is not very well developed in Mauss’s work and its lack of development is one among a number of problems. We need to engage more seriously with the embodied subjectivity and agency he hints at, drawing upon the work of other writers who have developed this theme (Crossley, 2001; Merleau-Ponty, 1962, 1965; Ryle, 1945; Sartre, 1969, 1972). Furthermore, we need to recognize more flexibility and room for imagination and improvisation in bodily action than he does (Crossley, 1995, 2004a). Finally, we need to do more to grasp the link between body techniques and the intercorporeal contexts in which they are practised. The sociality of body techniques, for Mauss, consists in their group specificity, but we must recognize also a form of sociality that consists in the way in which their performance is shaped to meet the interactive exigencies of specific situations (Crossley, 1995, 2004a). None of this detracts from the importance of Mauss’s innovation, however. His concept of ‘body techniques’ gives us a way of thinking sociologically about bodily activities, a way that prioritizes the social dimension while simultaneously building links to biology and psychology. This is a gain for theory, but it equally grows out of and facilitates solid empirical analysis, thereby providing muchneeded means to fill a gap within the sociology of the body.

Reflexive Body Techniques (RBTs)

Much of Mauss’s essay is devoted to an attempt to catalogue different body techniques according to their purposes and attributes. My concept of reflexive body techniques extends this effort. RBTs, as I define them, are those body techniques whose primary purpose is to work back upon the body, so as to modify, maintain or thematize it in some way. This might involve two embodied agents.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

10 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

Hairdressing, massage, dental work and cosmetic surgery, for example, usually entail that one ‘body’ is worked upon, physically, by another or by a team of embodied agents. It might even be extended to include such distanciated and mediated interactions as those that connect the manufacturers of pharmaceuticals to those who distribute and use them. Pill-popping is a socially complex, distanciated and mediated RBT. Equally, it can entail a single ‘body’ acting upon itself. This might involve one part of the body being used to modify/maintain another part; for example, when I use my hand to brush my hair or clean my teeth. It might, however, entail a total immersion of the body into a stream of activity whose purpose is to modify or maintain that body as a whole. When I jog, for example, I launch my whole body into action, in an effort to increase my fitness, burn off fat/calories, tone up my lower body, etc.

Each society or social group has a repertoire of RBTs. This repertoire is one element in the broader set of collective pre-representations of that society. And a portion of our daily routine is taken up performing techniques from this repertoire. We wash, clean our teeth, brush our hair, dress ourselves, perhaps shave and/or apply cosmetics. Other techniques from the repertoire are built into weekly or monthly routines. We exercise, shave parts of our body, have our hair cut, cut our finger nails, dress up for a night out, etc. And beyond our routines, we periodically venture ‘one-off’ modifications, such as a piercing, tattoos or cosmetic surgery, all of which involve bodily manipulation of the body; that is, RBTs. RBTs are techniques of the body, performed by the body and involving a form of knowledge and understanding that consists entirely in embodied competence, below the threshold of language and consciousness; but they are equally techniques for the body, techniques that modify and maintain the body in particular ways.

It might seem peculiar to regard the more mundane of these techniques as acquired aspects of a culture. As Mauss’s work shows, however, they do vary across societies. And, as Goffman has argued, they only seem mundane to those of us who have achieved sufficient temporal distance from the process of learning them to have forgotten that we did have to learn them, sometimes with difficulty:

To walk, to cross a road, to utter a complete sentence, to wear long pants, to tie one’s shoes, to add a column of figures – all these routines that allow the individual unthinking, competent performance were attained through an acquisition process whose early stages were negotiated in cold sweat. (Goffman, 1972: 293)

For practical purposes it also makes sense to refer to ‘ensembles’ of RBTs; that is, sets of techniques which are practised together for a common purpose. ‘Exercising’, ‘getting dressed’ and ‘putting on make-up’ are each examples of this. Each refers not to a single body technique but to a set (an ensemble) of techniques. It

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016