Body & Society-2005-Crossley-1-35

.pdf

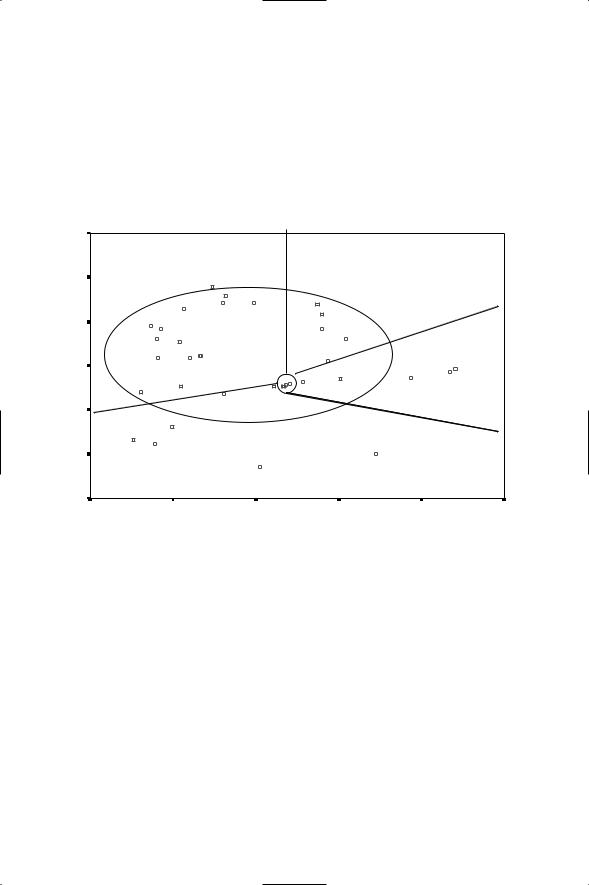

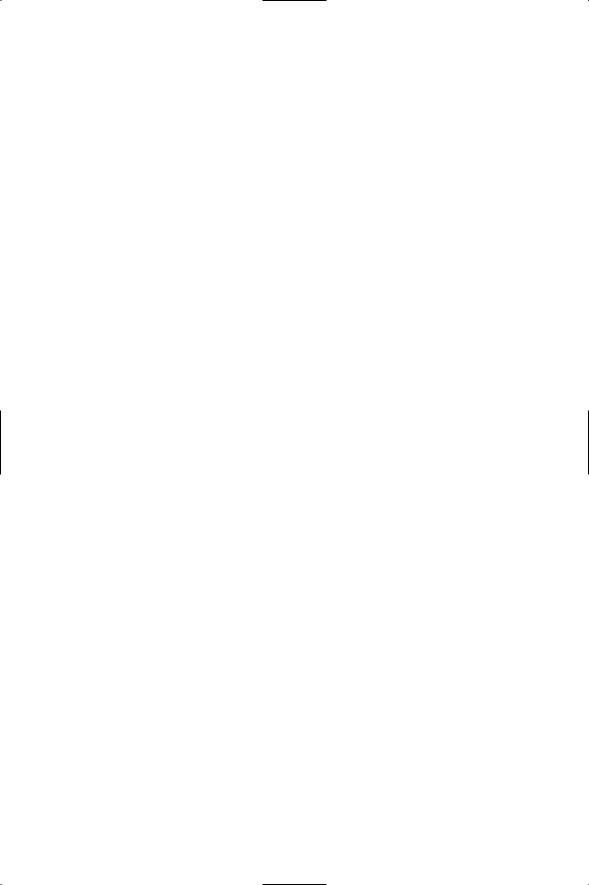

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 21

and competing subcultures, for example, such that placing them side by side in a common ‘marginal’ category paints a misleadingly homogeneous picture. To do justice to this we can attempt a two-, rather than a one-dimensional mapping of RBTs, using multi-dimensional scaling (see Figure 4).

As with all forms of multivariate statistics, multi-dimensional scaling offers contrasting methods for mapping data. As such we are forced to select the most

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

diet |

|

|

|

|

|

cossurg |

|

|

|

|

dyehair |

manicurecareful eat |

quick tan |

|

|

|

bellybutton |

|

floss |

|

|

|

|

sunbed |

|

|

|

1 |

paint f nails |

|

|

|

|

paint t nails |

|

vitamin supp |

|

|

|

|

cosmetics |

|

|

|

|

|

legpithair |

food supplement |

|

|

|

|

braceletnecklace |

steroid |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

breathfreshner |

bodybuilding supplem |

|

|

|

5-9hrs exercise |

|

||

|

earring |

after/perfumesunbathe |

|

|

|

|

combbath/swbruwwashnti/deohateethfaceairowernds |

|

|

||

|

1-4 hrs exercise |

ring |

|

|

|

–1 |

1-3 tattoos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

eyebrow |

|

|

|

|

|

tongue |

|

>3 tattoos |

|

|

–2 |

|

|

|

||

|

other pierce |

|

|

|

|

–3 |

|

|

|

|

|

–2 |

–1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Figure 4 A Radex Model Key

Reflexive techniques located in the inner circle of the radex. In the last 7 days: washed hair, used deodorant or antiperspirant, used perfume or aftershave, had a bath or shower, washed hands, washed face, brushed teeth.

Reflexive body techniques located outside of the inner circle but within the wider oval. In the last 7 days: worn a ring, worn a necklace, used cosmetics, worn an earring, worn a bracelet, eaten carefully for purposes of weight management, done between 1 and 4 hrs exercise. In last 4 weeks: shaved armpit hair, shaved leg hair, used a breath/mouth freshener, flossed, had or done a manicure, painted toenails, painted fingernails, dyed or coloured hair. In last 6 months: used any food supplement, used any vitamin supplement. In last 12 months: sunbathed, used a sunbed, used quick tan lotion. Had bellybutton pierced.

Reflexive body techniques located outside of the oval: got 1, 2 or 3 tattoos, got more than 3 tattoos, got an eyebrow piercing, got a tongue piercing, got another more ‘exotic’ piercing, done between 5 and 9 hrs exercise in the last week, used a bodybuilding supplement in the last 6 months, used steroids for bodybuilding purposes in the last 6 months, ever had cosmetic surgery, currently on a diet.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

22 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

appropriate mapping of variables from among a number of possibilities.12 Furthermore, outlying variables can skew maps inappropriately and sometimes have to be removed from the analysis. Nevertheless, with these points conceded, it is possible, as Figure 4 demonstrates, to map RBTs in the form of a ‘radex’ (as described earlier). Concentric circles demarcate frequency zones (from high to low as we move outwards from the centre), while segments demarcate seemingly meaningful and coherent clusters of practices. Our core zone is represented on this map by a tiny circle near its centre, containing a tight cluster of those RBTs which are nearly universally practised amongst the population surveyed. The techniques mapped here are so close in space that their labels overlap and are impossible to read (they are listed in the key to the map along with a fuller explanation of all labels). These core RBTs are less important for present purposes, however, than those orbiting them. The broader oval drawn around the inner circle is the boundary between the intermediate zone and the marginal zone. Those RBTs on the inside of the oval are intermediate, those on the outside are marginal. Most of the labels in these zones are easier to read but there is a slightly obscured cluster to the upper left of the central core, to the right of ‘bracelet’ (i.e. worn a bracelet in the last seven days), which contains ‘shaved leg hair’ and ‘shaved armpits’ (in previous four weeks), and overlaps slightly with ‘necklace’ (i.e. worn necklace in previous seven days).

This arrangement of concentric circles only tells us what the graph in Figure 3 tells us. The two-dimensional nature of the plot allows us to differentiate further among our RBTs, however. Specifically, we find that, as we move outwards from the central core, less frequently practised techniques begin to separate out from and cluster with one another in patterns which can be interpreted in broadly thematic terms. I have marked these clusters by way of segments. Thus, towards the top left of the map we find a cluster specifically related to the doing of femininity. Certain RBTs at either end of that cluster, such as exercising 1–4 hours a week, wearing a ring and being careful about what one eats (for reasons of weight management) are less gender specific but sandwiched between them we find all of the strongly (feminine) gendered RBTs. Moving clockwise from that segment we come to a more heterogeneous segment of techniques, which perhaps indicate an elevated level of ‘body consciousness’ relative to the norm but have little thematic unity apart from that. This segment involves techniques which serve both exclusively aesthetic (use of sunbed) and exclusively health-oriented (taking vitamins) ends, as well as techniques which could serve either/both end(s). It is possible, using MDS, to further differentiate the techniques in this section. Doing so I found that the techniques more closely associated with appearance tend to separate out from those associated with health, with

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 23

the ‘either/and’ techniques falling between, such that we can regard health and appearance as distinct thematic segments. I do not have the space to explore this any further here, however.

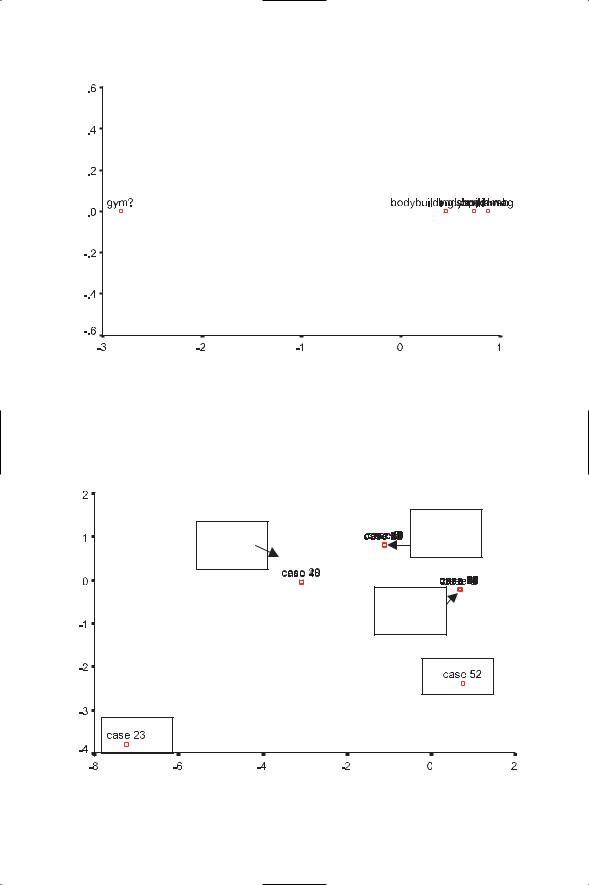

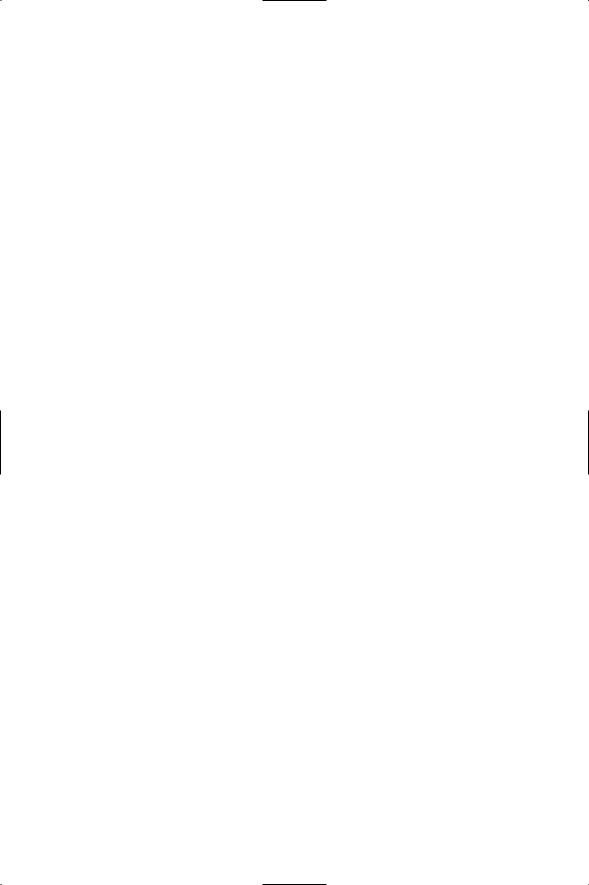

As we move further round we come to another more distinctive cluster, comprising 5–9 hours exercise a week, use of bodybuilding supplements and use of anabolic steroids for bodybuilding purposes. We might be tempted to deem this a bodybuilding cluster. As with any cluster, however, we can push our analysis further and differentiate within it. In this case, for purposes of illustrating MDS technique as much anything else, I have done this. In the first instance I selected from my sample only those respondents who had done more than five hours’ exercise in the previous seven days. I then reran the MDS analysis,13 selecting all variables with a direct relationship to bodybuilding: namely, working out with weights in a gym, reading bodybuilding magazines, visiting bodybuilding web-sites, taking bodybuilding food supplements and taking steroids (for bodybuilding purposes). The results, displayed in Figure 5(A), suggest a polarity between gym work and other bodybuilding practices. This indicates, as one might guess, that working out with weights in a gym is by no means indicative of ‘bodybuilding’. Many more people ‘work out’ than ‘bodybuild’.

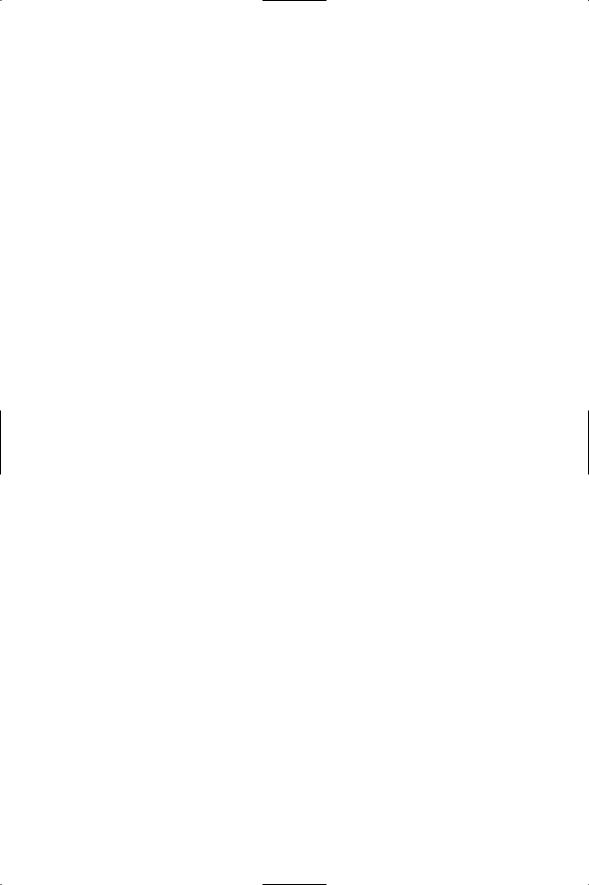

Pushing this further still, I ran the MDS analysis again,14 using the same respondents and variables, but this time mapping respondents (cases) rather than the variables. Using MDS in this way allows us to conduct a form of cluster analysis. We are able to see what sorts of ‘camps’ our respondents fall into when clustered according to specific variables, and which respondents fall into which camps.

The results for this analysis are given in Figure 5(B). In all, the 82 respondents who exercised for more than five hours in the seven days prior to filling in my questionnaire break down into five clear clusters which we can profile in terms of their relationship to the basic variables we have used in our MDS analysis (I double-checked this using hierarchical cluster analysis and achieved the same results).15 Seventy-eight of the respondents fall into one of two clusters (Cluster B and Cluster C). Cluster C contains all respondents who exercised for more than five hours but did not work out in the gym or engage in any bodybuilding-related practice (n = 55). Cluster B contains respondents who did work out in the gym but didn’t do any other bodybuilding-related activity (n = 23). Cluster A, to the left, contains two respondents, both of whom worked out in the gym and used a bodybuilding supplement. Further left again, in the bottom left corner, we have a single respondent (case 23) who registered positively for all indicators of bodybuilding, including steroid use. Finally, towards the bottom right of the plot we have ‘case 52’, a respondent

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

24 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

Figure 5(A) The ‘Bodybuilding’ Segment

(The obscured because overlapping variables at the right of Figure 5(A), are, from left to right, ‘use of a bodybuilding supplement’, ‘use of steroids’ and ‘consultation of bodybuilding websites’ [in identical positions], then ‘readership of a bodybuilding magazine’.)

|

Cluster B |

Cluster A |

n = 23 |

n = 2 |

|

|

Cluster C |

|

n = 55 |

Figure 5(B) A Cluster Analysis

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 25

who had exercised for over five hours in the previous seven days and had read a bodybuilding magazine in the previous month, but hadn’t worked out in the gym and hadn’t done anything else bodybuilding related. In effect then, the association between five hours+ exercise in a week and the various ‘bodybuilding’ variables turn out to be more complex than Figure 4 suggests. Most of the 82 respondents who did a lot of exercise didn’t do it in the gym, with weights, and the majority of those who did, did not engage in any other ‘bodybuilding’ RBTs. Only three respondents out of the 82 really ‘profile’ like bodybuilders on the closer inspection that this further analysis affords us. In addition, ‘case 52’ indicates that a person may do a lot of exercise and read about bodybuilding but not engage in the central RBT of the bodybuilding world (i.e. working out in the gym).

Having identified our clusters in this way we could, in a more detailed analysis, proceed to profile our clusters socially and, if we had the data, perhaps biographically also. I am not going to push the analysis in this direction, however. My purpose has simply been to show how we can use MDS to further extend the analysis of Figure 4. At which point we can return to it.

At the bottom of Figure 4 we have a cluster of tattooingand piercingrelated variables. These are widely spread, reflecting the fact that the ‘>3 tattoos’ and ‘1–3 tattoos’ variables are coded in a mutually exclusive fashion in the data set and so could not be positively associated, but their very distinct location, low on the plot, suggests a genuinely meaningful cluster based around these less conventional (perhaps primitivist-inspired) modifications. Interestingly, bellybutton piercing, which is also included on the plot, is located at some distance from this cluster (in the ‘feminine’ segment), suggesting that this particular type of piercing has a different location within the societal repertoire of RBTs. It has migrated beyond the bounds of an ‘alternative’ subculture on the margins into the mainstream (that is, the intermediate zone/feminine segment).

As my discussion of the ‘heavy exercise’ cluster demonstrates, Figure 4 is just the beginning of what could be a much more detailed analysis. Each cluster can be further analysed and mapped. As it stands, however, Figure 4 and my analysis of it are useful because they allow us to conceive of body modification/maintenance as a structured and differentiated social space. Moreover, they locate concrete practices in that space in accordance with real frequency distributions and real statistical associations. As such they invite and facilitate explanations that will advance our understanding of ‘body work’. In the final section of the article I offer a preliminary explanatory framework.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

26 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

Explaining Zones and Segments

Much work in the sociology of the body, as noted earlier, has tended to offer either very general accounts of body modification/maintenance, treating the RBTs which fall under this rubric as manifestations of a single phenomenon, or they have focused very specifically upon particular clusters of practices. The analysis above allows us to begin to move beyond both of these approaches. It facilitates an approach which focuses upon the whole range of modification/maintenance techniques but differentiates and distinguishes between them. Or again, which focuses upon the specificity of particular techniques/clusters but seeks, in doing so, to locate them on a broader map. Reconfiguring the problematic of body modification/maintenance in this way allows us to consider the different meanings of the techniques in these zones and the different types of circumstances in which they emerge; their different social logics. I can only hope to offer a preliminary analysis along these lines in this article, not least because a full analysis would require much more research. Nevertheless we can make a fruitful start.

The Core Zone

The core zone constitutes a cluster of practices which are ‘normal’ in both the statistical sense that most agents practise them and in the sense that they reflect pervasive social (moral) norms – specifically norms of hygiene in this case. The techniques belonging to this zone are integral to the construction of a self but not in the ‘choice’ and narrative-based sense suggested by Giddens (1991). They are too widely practised to reflect anything distinctive about the self, as Giddens’ conception of distinct narrative trajectories suggests, and their practice is too much a part of the taken-for-granted texture of the contemporary lifeworld to appear to agents as a matter of choice. One doesn’t choose to do these techniques in any meaningful sense. One just does them as matter of course. They are, to borrow Bourdieu’s (1979, 1989) term, doxic. This was revealed in my survey through the reactions of respondents to my questions. Several made it clear they felt it odd that I should ask about such matters as washing one’s face – ‘of course’ they had washed their face in the last seven days! Moreover others jokingly feigned offence at being asked.

The fact that respondents were able to claim moral injury is important as it indicates the normative aspect that attaches to these practices and suggests that, insofar as they play a role in the construction of selfhood, these techniques attach to a very basic level of selfhood and recognition. Techniques in the core zone represent a threshold that must be crossed if the agent is to be accepted as a

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 27

competent member of their society. Indeed, it is not uncommon for workers in mental health and other welfare services to take non-performance of these techniques as indications that intervention is necessary because the agent being scrutinized is unable to ‘care for themselves’. They are deemed ‘incompetent’. This is another reason why I would say that these techniques are not chosen. They are enforced and expected. Non-compliance is punished, usually through the informal sanctions of peers but sometimes through the specialized interventions of a variety of agents of normalization who collectively comprise the ‘carceral network’ of late modern societies (Foucault, 1979, 1980). The other side of this is that agents are expected to have a right to perform these RBTs. Commentators on life in total institutions, for example, often suggest that restricted access to the equipment required for these techniques and/or loss of effective control over them is extremely damaging and represents a powerful assault upon self (Bettelheim, 1986; Goffman, 1961).

The techniques in the core zone are much more likely to be oriented to maintenance than modification of the body, at least in the sense that they reproduce sameness through time. Moreover, their temporal structure is more likely to be repetitive than transitional. They structure, by punctuating, the lived time of the agent in a predictable because repetitive pattern. What belongs to this core zone is historically variable in the longer term, however. A cursory glance at Elias’s (1984) account of the civilizing process or Nettleton’s (1992) genealogy of dentistry, for example, indicates that these core practices of contemporary society have not always been so (see also Gurney, 2000; Mort, 1987). The question of how these practices emerge and achieve both their extensive diffusion and their taken-for-grantedness goes beyond the remit of this article. There is no reason to suppose that there is only one path to the ‘core zone’. And I cannot begin to trace the many distinct paths that specific RBTs and ensembles have followed. However, drawing from the accounts cited above one might tentatively suggest that the core zone identified in my survey is the effect of: (i) a search for distinction among aspiring groups, whose techniques have then been variously adopted by ‘the lower orders’ on account of their kudos and/or imposed upon them by charitable and philanthropic movements representing those (once aspiring now dominant) groups, extending their dominance; (ii) the struggles of different professional groups (e.g. dentists and public health officials) and the strong position they have been able to secure for themselves within the power balances of welfare societies; (iii) the influence of the hygiene and cosmetics industries. Struggles for domination and balances of power are central in each case here and, as such, my designation of the core zone, following Bourdieu (1979, 1989), as doxic, is doubly apposite. The taken-for-grantedness of the techniques falling

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

28 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

within this zone is an effect of power balances which enforce their normalcy and involves a forgetting of the historical struggles involved in the achievement of that state of normalcy.

The Intermediate Zone

As we move out from the core zone, into the intermediate zone, we enter a more differentiated space (as indicated by the segmentation which cross-cuts the intermediate zone), which cannot be accounted for by a single explanation. What we find in this zone, on one hand, are techniques that demarcate key categorical distinctions in our society, particularly those of gender; techniques that, for the incumbents of these categories, might still be doxic. In fact, as we saw in Table 1, there is a frequency distribution of these RBTs among females too; some are core, some intermediate and some marginal. Given more space for analysis we might construct a radex of these RBTs too, drawing out not only their broad frequency distribution but equally their thematic/associational clustering (pushing the analysis further as I did for the bodybuilding segment in Figure 5). For the present it must suffice to say that the doxic nature of ‘core’ feminine techniques is as likely an effect of struggles and power balances as those of the more general core zone. This is, of course, the argument of many key accounts of the doing of femininity (Bartky, 1993; Connell, 1987).

The gender segment is only one among a number in the intermediate zone, however. In addition we find a selection of practices relating variously to the health and appearance of the body. These RBTs, arguably, are better accounted for by notions of choice and active self-construction. Fewer people practise them, so that they can serve to distinguish and mark out a distinct identity. And because they are less widely practised their appropriation is less likely to be obvious, taken for granted and expected, and more likely to be a matter of choice. Although informal pressures may attach to these RBTs no formal institutional mechanisms exist to enforce them, beyond the seductive allure of the fashion and advertising industries. Having said this, these techniques may well become habitual and routinized for specific agents. Moreover, we should not discount the possibility that an agent’s choices and narratives are affected by their resources (economic, cultural, symbolic and social), by the exigencies of their situation, by the particularities of their biographical trajectory and by features of the collective habitus which they share with similarly resourced/situated agents. As noted above, the statistical evidence for a class–RBTs association is weak. A wider and more focused analysis might find differences here, however. And of course other broad social groupings or categories may mark out their distinction within this zone too, forming a distinct segment within it – as in the feminine segment.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 29

Like the core zone, the intermediate zone is historically variable. It is subject to the movements of fashion, and contains practices which might previously have belonged either to the core or the marginal zone. Indeed, it is not at all uncommon for techniques from the marginal zone, a zone of innovation and experimentation, to migrate into the intermediate zone after being appropriated by the fashion and advertising industries. Likewise, when these techniques fall out of fashion they will tend to fall back into the marginal zone. And migration can occur between the core and intermediate zones also. Once fashionable techniques, appropriated because they mark distinction, can, as noted above, be appropriated by moralizing movements intent on imposing them upon society as a whole, or alternatively can become so fashionable as to outgrow fashion (and certainly their power of distinction) to become normal.

The Marginal Zone

The marginal zone too is highly differentiated. It is, as noted above, a site of innovation and proto-fashion but also perhaps a wasteland for démodé techniques. The techniques in this zone are statistically deviant. Some will belong to distinct social movements or social fields, such as modern primitivism or bodybuilding. And some of these, such as primitivism, will represent a current of resistance against the doxa and orthodoxy of the mainstream and core zones. They express a resistance or activist habitus (see Crossley, 2002 and esp. 2003). Some, like bodybuilding, will involve practices, such as the use of steroids, which are illegal. Some, however, might be socially defined as manifestations of individual ‘psychopathology’. The practices associated with ‘deliberate selfharm’, ‘anorexia nervosa’ and ‘bulimia nervosa’ (not included in my survey) are examples of this (on these practices and the social movements mobilizing around them see Cresswell, 2003). In some cases these ‘psychopathological’ RBTs are very difficult to dissociate from the more extreme techniques of, for example, modern primitivism; particularly as the former have become a focus of social movement mobilization and subcultural elaboration. Mobilization blurs the distinction, often used by psychiatrists, between individual ‘pathology’ and subcultural variation. They are at least distinct, however, in the sense that they have not achieved the recognition afforded to primitivism, performance art (another movement at the margin) and bodybuilding. The latter, while regarded as weird and immoral by many, and often criticized because they are said to involve damage to the body, have achieved at least a sufficient degree of acceptance to keep the agents of psy-complex at bay. They are not completely free of attempts to regulate and police them, on account of the belief that they often transgress the law (e.g. steroid use) or basic standards of decency, but

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

30 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

they are not officially pathologized as deliberate self-harm as the eating disorders are.

The politics and deviancy attaching to techniques in the marginal zone sets them aside from the practices of the intermediate zone – even if some of them eventually make it into that zone. These techniques are not accepted as legitimate choices and generally have social sanctions, formal and informal, attached to them. To engage with them one must disengage from the broader societal community, whether deliberately or not. As such they betray a different social logic to that of practices in the intermediate and core zones. On one level it is arguable, following Giddens (1991), that they reflect existential projects and choices (see also Monaghan, 1999; Sweetman, 1999), perhaps profoundly so. However, there is an element of transgression here that is not adequately captured by a generic and undifferentiated existential account. Electing to be branded with red hot irons or to push one’s muscular development to the level of the bodybuilder, given the social stigmatization and other sanctions that attach to such modifications, and that practitioners know attach to them, distinguishes them clearly from RBTs which are accepted, encouraged or enforced. They thus require a different type of explanation. The practices in this zone reflect relatively closed social fields, which valorize otherwise disvalued practices, offering alternative configurations of meaning for them, and/or relatively closed individual phenomenological fields which do likewise. To fully understand the segments in this zone we would need to look to a form of social movement or subcultural analysis and/or methods more sensitive to individual biographical trajectories and phenomenological fields, such as ‘existential psychoanalysis’ (Sartre, 1969). Moreover, to distinguish between segments in this field it might also be necessary to focus upon the relative balances of power and social conditions that allow some (e.g. performance artists and modern primitives) to successfully pass off their activities as subversive actions, while the actions of others (e.g. self-harmers) are effectively pathologized.

As noted above, however, the marginal zone too is historically variable. Most techniques begin life as the practices of a small minority, and some of these practices will go on to become the techniques of a majority or large minority, perhaps even normal techniques within a given society or group. Their marginality, at least qua practices, is in this sense a relational phenomenon. Any account of RBTs must be sensitive to such historical movement across zones.

There is much more work to be done to fill out this explanatory framework. I have not even begun to address the fact, for example, that ‘body work’ is located in a context that engenders all kinds of involuntary bodily changes which, in turn, agents seek to compensate for and ‘correct’ – the contemporary trend

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016