3D Game Programming All In One (2004)

.pdf

358Chapter 11 ■ Structural Material Textures

With tools like Paint Shop Pro you have a wide variety of means for creating textures, including a specific Texture Effects tool in the Effects menu, as shown in Chapter 8. Figure 11.12 shows examples of textures created using the built-in features of Paint Shop Pro. I encourage you to explore this tool in depth. It can really be a timesaver. And you can use it to create some knockout textures.

|

|

Scaling Issues |

|||

|

|

When creating your textures, you will need to pay |

|||

|

|

attention to the issue of scale. The sizes of the things |

|||

|

|

within an image that is used to make a texture have a |

|||

|

|

particular relationship to other real-world objects. We |

|||

|

|

are subconsciously aware of many of these relation- |

|||

|

|

ships from our exposure to the world in general and |

|||

|

|

will notice when the textures are out of proportion to |

|||

|

|

the items they adorn. If it's bad enough the effect can |

|||

|

|

sometimes be similar to the sound of fingernails being |

|||

Figure 11.12 |

Example textures. |

||||

dragged across a chalkboard! |

|||||

|

|

|

|

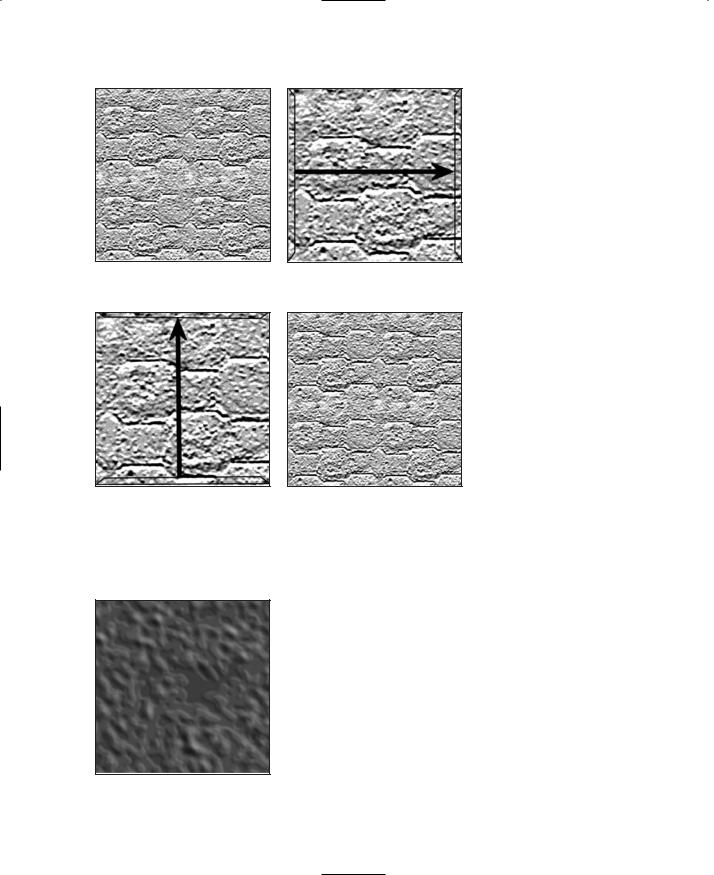

Figure 11.13 shows two stylized houses. |

|

|

|

|

|

The bricks in house A are far too large, |

|

|

|

|

|

while the bricks in house B are more |

|

|

|

|

|

appropriately sized, yet may still be a bit |

|

|

|

|

|

too large. Yes, there are some uses for |

|

|

|

|

|

stone blocks having proportions such as |

|

|

|

|

|

those in house A, but they are rarely |

|

|

|

|

|

used in bungalow-sized or two-story |

|

Figure 11.13 |

Scaling bricks. |

|

|

homes, as depicted in the figure. |

|

|

|

|

The scale issue can pop up anywhere, as you |

||

|

|

|

can see in Figure 11.14. The texture image in |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

the corrugated metal bridge surface is probably |

||

|

|

|

about 10 times larger than is appropriate. |

||

|

|

|

Sometimes you might need to redo the texture |

||

|

|

|

to match—other times you can adjust how the |

||

|

|

|

texture is applied to the polygons using the |

||

|

|

|

modeling tools. My rule of thumb is that if the |

||

|

|

|

texture image size is 64 pixels by 64 pixels or |

||

|

|

|

smaller and needs to be made larger, you |

||

|

|

|

should make a new texture at the larger size. |

||

Figure 11.14 |

Scaling error. |

|

The same goes the other way: If the image size |

||

Team LRN

Tiling 359

is larger than 64 pixels by 64 pixels and needs to be made smaller, then make a new texture at the smaller size.

Tiling

Many structures have large surfaces with repeating patterns. The best way to approach making textures for these surfaces is to create one smaller texture that is replicated many times across the surface, rather than simply making one large texture.

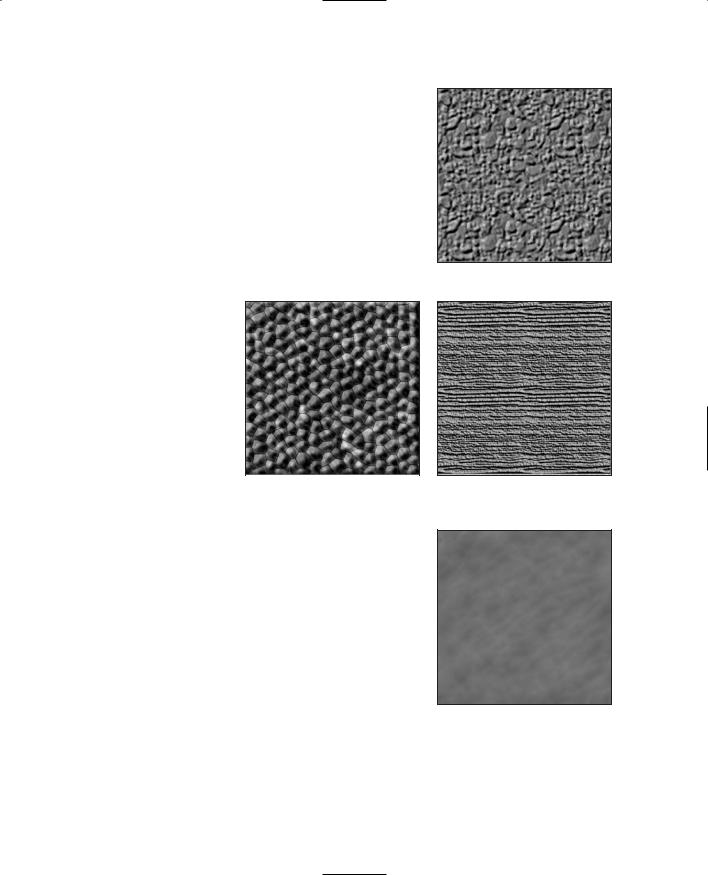

The replication will usually take place in two dimensions. It is important to make sure that the edges of the texture align properly when they meet. Figure 11.15 shows this to good effect. You can see the obvious horizontal as well as the more subtle artifacts in house A where the tiled brick textures don't quite line up. In house B, where care was taken to ensure that the texture edges matched up correctly, those artifacts aren't visible.

However, in house B in Figure 11.15 there |

|

is another obvious artifact of tiling, this |

|

time caused by asymmetric lighting |

|

effects in the texture shading. You can see |

|

each repeated texture tile—its position is |

|

marked by the presence of the darker |

|

shaded bricks in a repeated pattern. This |

|

effect can be quite subtle and difficult to |

|

detect in an image viewed in isolation. |

Figure 11.15 Tiled brick texture. |

Figure 11.16 shows the texture used in house B of Figure 11.15. Looking at it in isolation, you would be hard pressed to notice the subtly darker shaded bricks.

The simplest way to fix up a texture for use as a tiled texture is to copy the left edge, about 5 or 10 pixels wide, mirror the copy horizontally, and then paste the copy on the right side of the image. Do the same for the bottom edge. Of course, you can go from top to bottom or right to left as well. The important step is the mirroring.

After placing the mirrored edges, spend a little time blending their inner edges with the interior portions of the image.

Figure 11.17 shows a stone block texture that is a candidate for use in a tiling situation.

Figure 11.18 shows the texture tiled in a set of four. Again, you can see the artifacts caused by the mismatched edges.

Figure 11.16 The brick texture with asymmetric shading.

Figure 11.17 A stone texture.

Team LRN

360 Chapter 11 ■ Structural Material Textures

Figure 11.18 Poorly tiled stone texture.

Figure 11.20 Replicating the bottom edge.

Figure 11.19 Replicating the left edge.

Figure 11.21 Properly tiled stone texture.

Figure 11.19 shows the left edge being copied, mirrored, and placed on the right.

Figure 11.20 shows the same thing happening with the bottom edge.

Finally, Figure 11.21 shows the tiled result.

Texture Types

There are far too many texture types and classes of material appearances for me to enumerate them with any sort of thoroughness. Given that, there is a much smaller set of texture types that are found over and over in nature and man-made structures.

Most of the following textures are types that are used for buildings, bridges, and other man-made items in a game world.

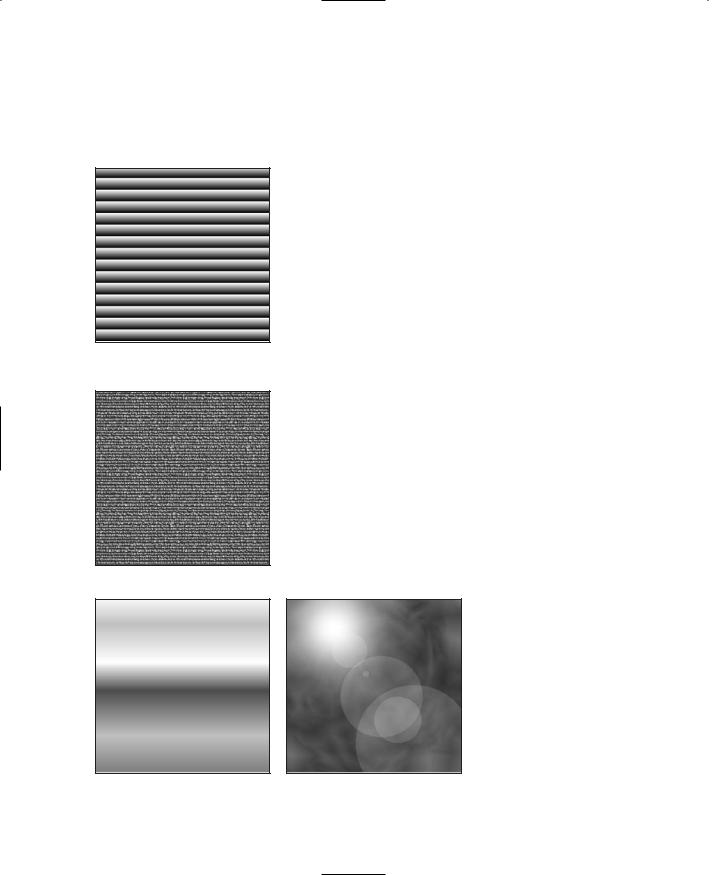

Irregular

Irregular textures tend to have a general disorder and random appearance, like that shown in Figure 11.22. Dirt and grass are examples of irregular textures. Quite often irregular textures are combined with other, different irregular textures in order to give a weathered or damaged appearance to an area or surface.

Figure 11.22 An irregular texture.

Team LRN

Rough

Rough textures, as shown in Figure 11.23, sometimes have somewhat the same sense about them as irregular textures. They are often used as tiles on a surface like a sidewalk or rough concrete walls.

Pebbled

Pebbled textures are another example of textures often used for paved surfaces and stone walls. Tarmacadam pavement is an example of a finely pebbled surface when viewed from a distance

of about 5 or 6 feet. Figure 11.24 shows a more obvious pebbled texture that could be used for a wall or decorative planter.

Woodgrain |

|

|

Figure 11.25 shows a |

|

|

woodgrain texture that |

|

|

Figure 11.24 A pebbled |

||

has many highly variant |

||

texture. |

||

bundles of lines rang- |

||

|

ing from fine to coarse that run roughly parallel to each other, sometimes interrupted by swirls and knots. Some kinds of stone have similar appearances.

Smooth

We all know when something is smooth—there are no discernable bumps or irregularities to our touch. Depicting smoothness in textures can be a little difficult. We usually create a rather bland surface look and then introduce a few soft and mild irregularities in order to emphasize the smoothness. Figure 11.26 shows a smooth texture.

Texture Types |

361 |

Figure 11.23 A rough texture.

Figure 11.25 A woodgrain texture.

Figure 11.26 A smooth texture.

Team LRN

362 Chapter 11 ■ Structural Material Textures

Patterned

Patterned textures are pretty straightforward. The intent is not necessarily to convey the contour, bumpiness, or feel of a surface, but rather to represent regular shapes or patterns that appear on an item. Figure 11.27 depicts a pattern that could be used to represent the louvers of an air duct

in a wall.

Figure 11.27 A patterned texture.

Fabric

Fabric textures emulate the appearance of things like canvas or carpet. Fabrics may be woven or not, but they all tend to exhibit fine repetitive shapes. Figure 11.28 shows a woven fabric texture that could be canvas.

Metallic

Metallic textures tend to have a dominant color, with a strong dark shadow that follows the outer contours of the metallic object and a bright accent color that runs along raised surfaces. Figure 11.29 shows a texture that could be used for a metal tube.

Reflective

A reflective texture simulates the effect of a light source in the scene reflecting strongly off the surface of the textured object. Figure 11.30 is such a texture that might be depicting a bright overhead light reflecting off a window.

Figure 11.28 A fabric texture.

Figure 11.29 A metallic texture.

Figure 11.30 A reflective texture.

Plastic

Plastic textures are similar to metallic textures in their manner of shading and highlighting. Plastic tends to have more of an oily appearance to it at times, so the shading and highlights are often more sinuous. As shown in Figure 11.31,

Team LRN

|

Moving Right Along |

363 |

the highlights tend to be less clearly defined than with |

|

|

|

|

|

metallic textures, while the light source often appears as |

|

|

a distinct highlight. |

|

|

Moving Right Along |

|

In this chapter, we examined how to collect images to use |

|

in applying textures to objects that represent real-world |

|

structures. We saw some of the processing techniques that |

|

we may need to use to prepare our images for use as tex- |

|

tures, like color matching and cropping. |

Figure 11.31 A plastic texture. |

|

Some of the areas that can be more problematic when

considering textures for structures are scaling the images and preparing them to be "tiled" if the texture will be used in a repeating fashion. A texture that can be tiled is one whose opposite edges can be mated together without producing a noticeable seam.

Finally, we explored some of the more common texture patterns and characteristics that are used in games.

In the next chapter, we will look at terrains, which are often used to provide that touch of realism in our game worlds. Some of the ideas we've covered in this chapter will certainly be useful in the next chapter as well.

Team LRN

This page intentionally left blank

Team LRN

chapter 12

Terrains

Many games take place exclusively inside buildings or structures, like tunnels. And many other games involve exclusive outdoor game play. Then there are some games that have a mix of each.

When your game has an outdoor component, you need to represent the terrain, which in game terms is the combination of the topography (hilliness, for example) and ground cover (grass, gravel, sand, and so on). The topography is modeled using a 3D model, and the ground cover is represented by textures.

In addition to representing the ground, you also need to represent the sky, if you want to have interesting outdoor game play. Typically, a construct called a skybox is used to represent all of the sky, from horizon to horizon.

Terrains Explained

To understand terrains in a game development context, we need to look at the characteristics of the terrain we want to model. These characteristics will drive our need for the data that defines the terrain we want to make and therefore will heavily influence how and where we obtain that data.

Terrain Characteristics

A basic unit of terrain is the tile. Essentially a terrain tile is a collection of polygons that form a

3D model that represents the terrain, as depict-

Figure 12.1 An untextured terrain tile. ed in Figure 12.1. 365

Team LRN

366Chapter 12 ■ Terrains

When we model terrain in a game, there are a number of choices we have to make. We need to decide the level of terrain fidelity we want to achieve. Another choice is to figure out the spread of the terrain. Finally, we need to decide what sort of freedom the terrain embodies. Table 12.1 lists characteristics and the ramifications of each of these choices.

Table 12.1 Terrain Characteristics

Characteristic Description

Fidelity |

Terrain fidelity measures how accurately the terrain reflects real topography found |

|

somewhere in the world—how realistic it is. The realism can be reflected in both the |

|

modeling and the textures. Modeling fidelity can be described as any of the following: |

|

Realistic: Accurate at 1:1 scale in all dimensions with high-resolution textures |

|

representing the terrain cover. |

|

Semirealistic: Accurately scaled, usually to a smaller size. Often the vertical |

|

scale is 1:1 while the horizontal scales are around 1:2. The game World War II |

|

Online by Cornered Rat Software has all of Western Europe modeled in this |

|

fashion. The game uses medium-to-low resolution textures to represent |

|

ground cover. |

|

Quasi-Realistic: Not accurately scaled in any dimension, but still attempts to |

|

represent a real location in the world. Usually employs high-resolution ground |

|

cover textures. The scales and textures are chosen to give a sense of the locale |

|

that works well in the game environment. NovaLogic's Delta Force series |

|

takes this approach. |

|

Unrealistic: Everything else! Unrealistic terrain is most commonly used to |

|

specifically enhance game play or the backstory of the game. |

Spread |

Terrain spread is the degree to which areas of the terrain are unique. Terrain is created in |

|

units called tiles. The spread is related to these tiles in one of three ways: |

|

Infinite: A square terrain region is repeated, or tiled, in all cardinal directions, such |

|

that when the player leaves a region to the west, he enters a new copy of the |

|

same terrain tile from the east. This continues for as long as the player keeps |

|

moving in that one direction. |

|

Finite: The terrain tiles are repeated in all directions, but at some point the |

|

repetition stops. |

|

Untiled: Terrain tiles are not repeated. |

Freedom |

Terrain freedom is the measure of how much the player's in-game movements are |

|

restricted by the terrain. Terrain freedom is closely coupled with terrain spread. There are |

|

really only two degrees of terrain freedom: |

|

Closed: Closed terrain limits player movements in all cardinal directions at some |

|

point. With closed terrain, at some point after a player has been moving in a |

|

particular direction, he cannot continue that way, either because there is a virtual |

|

physical barrier or because the program prevents further movement. In any case, |

|

the terrain is usually modeled beyond the barrier only as far as the player can |

|

see. After that—nothing. |

|

Open: Open terrain allows player movement in any direction for as long as the |

|

player wants. Some games will warp the player to the "other side" of the world, |

|

where he will keep crossing terrain tile copies until he returns to the place he started. |

Team LRN

Terrain Modeling |

367 |

There are practical considerations that direct our terrain design choices. Many game engines simply aren't capable of handling the distances involved in large-scale terrains or the number of objects required to appropriately populate them. Some game genres aren't suited to open terrains—the player needs to be confined in order to advance the game story as required.

Terrain Data

When you want to create a high-fidelity terrain model of a real place in the world, you are going to need to get the data from somewhere. If the area in question is small enough, you may be able to go out and gather the information yourself if you're handy with a theodolite (a surveyor's tool). You might be able to glean the necessary information from topographic maps. In either case there is a lot of work involved in the data gathering phase alone. You will need accurate distance measurements and altitudes, as well as photos of the ground cover.

But don't despair! There are sources for high-resolution terrain information available on the Internet. If you go to http://edcwww.cr.usgs.gov, the Web portal for the United States Geological Survey (USGS; part of the U.S. government), you can find a wealth of terrain data.

The data is available in several forms, but the standard form is the DEM (Digital Elevation Model). DEM-formatted data files have the .dem file extension. Another format in use is the DTM (Digital Terrain Model), which uses the .dtm file extension. Finally, a powerful and complex format called SDTS (Spatial Data Transfer Standard) also exists but is not in wide use outside of scientific niches. SDTS files are denoted by the .ddf file extension.

In any event, the ground cover information is not included in these various model formats, so you'll need to gather that as well. Again, the USGS comes in handy with its satellite imagery—some of it taken down to a resolution of less than a meter per image pixel.

DEM files provide elevation information for specific coordinates of places on Earth. DEM files can be converted to a format used by game engines called a height map. We won't go into detail about how to use DEM data for your game, but you can use several of the resources listed in the appendixes to locate the data and tools needed.

Terrain Modeling

There are basically two approaches that 3D game engines use to model terrain in a 3D world. In both cases 3D polygon models represent terrains.

In the external method we include the terrain as just another object in the game world. This method offers much freedom of manipulation. You can rotate the terrain model, skew it, and otherwise subject it to all manner of indignities. All 3D engines support this approach. While flexible, it is usually an inefficient way to render complex large terrains.

Team LRN