A Dictionary of Science

.pdf

supplementary units |

796 |

upwards with the radius and ulna parallel.

Compare pronation.

supplementary units See si units.

suppressed-carrier transmission See transmitter.

suppressor grid A wire grid in a pentode *thermionic valve placed between the *screen grid and the anode to prevent electrons produced by *secondary emission from the anode from reaching the screen grid.

supramolecular chemistry A Üeld of chemical research concerned with the formation and properties of large assemblies of molecules held together by intramolecular forces (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals’ forces, etc.). One feature of supramolecular chemistry is that of selfassembly (see self-organization), in which the structure forms spontaneously as a consequence of the nature of the molecules. The molecular units are sometimes known as synthons. Another aspect is the study of very large molecules able to be used in complex chemical reactions in a fashion similar to, for example, the actions of the naturally occurring haemoglobin and nucleic acid molecules. Typical examples are the *helicate and *texaphyrin molecules and *dendrimers. Such molecules have great potential in such areas as medicine, electronics, and optics. The Üeld also includes host–guest chemistry, which is concerned with molecules speciÜcally designed to accept other molecules. Examples include *crown

sethers, *cryptands, and *calixarenes. suprarenal glands See adrenal glands.

surd A quantity that cannot be expressed as a *rational number. It consists

of the root of an arithmetic member (e.g. √3), which cannot be exactly determined, or the sum or difference of such roots.

surface tension Symbol γ. The property of a liquid that makes it behave as if its surface is enclosed in an elastic skin. The property results from intermolecular forces: a molecule in the interior of a liquid experiences a force of attraction from other molecules equally from all sides, whereas a molecule at the surface is only

attracted by molecules below it in the liquid. The surface tension is deÜned as the force acting over the surface per unit length of surface perpendicular to the force. It is measured in newtons per metre. It can equally be deÜned as the energy required to increase the surface area by one square metre, i.e. it can be measured in joules per metre squared (which is equivalent to N m–1).

The surface tension of water is very strong, due to the intermolecular hydrogen bonding, and is responsible for the formation of drops, bubbles, and meniscuses, as well as the rise of water in a capillary tube (capillarity), the absorption of liquids by porous substances, and the ability of liquids to wet a surface. Capillarity is very important in plants as it is largely responsible for the transport of water, against gravity, within the plant.

surfactant (surface active agent) A substance, such as a *detergent, added to a liquid to increase its wetting properties by reducing its *surface tension.

surveying The practice of accurately measuring and recording the relative altitudes, angles, and distances of features on, above, or below the land surface from which maps and plans can be plotted. Surveying is necessary to locate and measure property lines; to lay out buildings, bridges, roads, dams, and other constructions; and to obtain topographic information for mapping and charting. A number of methods are used depending on the degree of precision that is required. The chief methods include triangulation, trilateration, levelling (see level), plane tabling, and traversing.

susceptance Symbol B. The reciprocal of the *reactance of a circuit and thus the imaginary part of its *admittance. It is measured in siemens.

susceptibility 1. (magnetic susceptibility) Symbol χm. The dimensionless quantity describing the contribution made by a substance when subjected to a magnetic Üeld to the total magnetic Ûux density present. It is equal to µr – 1, where µr is the relative *permeability of the material. Diamagnetic materials have a low negative susceptibility, paramagnetic materials have a low positive susceptibility, and fer-

797 |

sympathetic nervous system |

romagnetic materials have a high positive value. 2. (electric susceptibility) Symbol

χe. The dimensionless quantity referring to a *dielectric equal to P/ε0E, where P is the electric polarization, E is the electric intensity producing it, and ε0 is the electric constant. The electric susceptibility is also equal to εr – 1, where εr is the relative *permittivity of the dielectric.

suspension A mixture in which small solid or liquid particles are suspended in a liquid or gas.

suture The line marking the junction of two body structures. Examples are the immovable joints between the bones of the skull and, in plants, the seam along the edge of a pea or bean pod.

swallowing See deglutition.

swash A surge of turbulent seawater that rushes up the shore after a wave breaks; it runs back down the slope as a backwash. The swash can carry materials, such as driftwood, seashells, and seaweed, which are often left on the beach as a line marking the extent of high tide. On a falling tide the backwash may form a series of channels.

sweat The salty Ûuid secreted by the *sweat glands onto the surface of the skin. Excess body heat is used to evaporate sweat, thereby resulting in cooling of the skin surface. Small amounts of urea are excreted in sweat.

sweat gland A small gland in mammalian skin that secretes *sweat. The distribution of sweat glands on the body surface varies between species: they occur over most of the body surface in humans and higher primates but have a more restricted distribution in other mammals.

swim bladder (air bladder) An air-Ülled sac lying above the alimentary canal in bony Üsh that regulates the buoyancy of the animal. Air enters or leaves the bladder either via a pneumatic duct opening into the oesophagus or stomach or via capillary blood vessels, so that the speciÜc gravity of the Üsh always matches the depth at which it is swimming. This makes the Üsh weightless, so less energy is required for locomotion. In lungÜsh it also has a respiratory function. The lungs

of tetrapods are homologous with the swim bladder, which has developed its hydrostatic function by specialization.

syconus A type of *composite fruit formed from a hollow Ûeshy inÛorescence stalk inside which tiny Ûowers develop. Small *drupes, the ‘pips’, are produced by the female Ûowers. An example is the Üg.

sylvite (sylvine) A mineral form of *potassium chloride, KCl.

symbiont An organism that is a partner in a symbiotic relationship (see symbiosis).

symbiosis An interaction between individuals of different species (symbionts). The term symbiosis is usually restricted to interactions in which both species beneÜt (see mutualism), but it may be used for other close associations, such as *commensalism. Many symbioses are obligatory (i.e. the participants cannot survive without the interaction); for example, a lichen is an obligatory symbiotic relationship between an alga or a cyanobacterium and a fungus.

symmetry 1. (in physics) The set of invariances of a system. Upon application of a symmetry operation on a system, the system is unchanged. Symmetry is studied mathematically using *group theory. Some of the symmetries are directly physical. Examples include reÛections and rotation for molecules and translation in crystal lattices. Symmetries can be discrete (i.e. have a Ünite number), such as the set of rotations for an octahedral molecule, or continuous (i.e. do not have a

Ünite number), such as the set of rotations s for atoms or nuclei. More general and ab-

stract symmetries can occur, as in the symmetries associated with *gauge theories. See also broken symmetry; supersymmetry. 2. (in biology) See bilateral

symmetry; radial symmetry.

sympathetic nervous system Part of the *autononomic nervous system. Its nerve endings release noradrenaline or adrenaline as a neurotransmitter and its actions tend to antagonize those of the *parasympathetic nervous system, thus achieving a balance in the organs they serve. For example, the sympathetic nervous system decreases salivary gland secretion, increases heart rate, and

sympatric |

798 |

constricts blood vessels, while the parasympathetic nervous system has opposite effects.

sympatric Describing groups of similar organisms that, although in close proximity and theoretically capable of interbreeding, do not interbreed because of differences in behaviour, Ûowering time, etc. See isolating mechanism. Compare allopatric.

symphysis A *joint that is only slightly movable; examples are the joints between the vertebrae of the vertebral column and that between the two pubic bones in the pelvic girdle. The bones at a symphysis articulate by means of smooth layers of cartilage and strong Übres.

symplast The system of *protoplasts in plants, which are interconnected by *plasmodesmata. This forms a continuous system of cytoplasm bounded by the plasma membranes of the cells. The movement of water through the symplast is known as the symplast pathway. It is the only means by which water crosses the *endodermis. Compare apoplast.

sympodium The composite primary axis of growth in such plants as lime and horse chestnut. After each season’s growth the shoot tip of the main stem

stops growing (sometimes terminating in a Ûower spike); growth is continued by the tip of one or more of the lateral buds.

Compare monopodium.

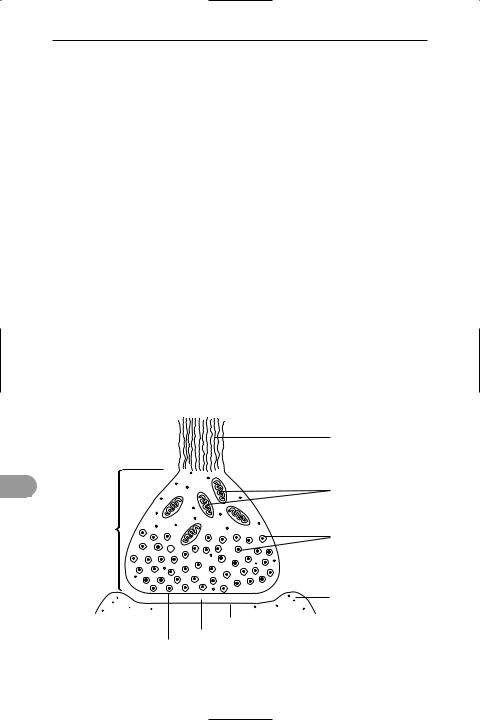

synapse The junction between two adjacent neurons (nerve cells), i.e. between the axon ending of one (the presynaptic neuron) and the dendrites of the next (the postsynaptic neuron). The swollen tip of the axon of the presynaptic neuron, called the synaptic knob, contains vesicles of *neurotransmitter substance. At a synapse, the membranes of the two cells (the pre- and postsynaptic membranes) are in close contact, with only a minute gap (the synaptic cleft) between them. A nerve *impulse is transmitted across the synapse by the release from the presynaptic membrane of neurotransmitter, which diffuses across the synaptic cleft to the postsynaptic membrane. This triggers the propagation of the impulse from the dendrite along the length of the postsynaptic neuron. Most neurons have more than one synapse. See also excitatory postsynaptic potential.

synapsis (in genetics) See pairing.

syncarpy The condition in which the female reproductive organs (*carpels) of a Ûower are joined to each other. It occurs,

end of axon of presynaptic neuron

s |

mitochondria |

synaptic knob

synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitter

dendrite of postsynaptic neuron

postsynaptic membrane

synaptic cleft presynaptic membrane

Structure of a synapse

799 |

synergism |

for example, in the primrose. Compare apocarpy.

synchrocyclotron A form of *cyclotron in which the frequency of the accelerating potential is synchronized with the increasing period of revolution of a group of the accelerated particles, resulting from their relativistic increase in mass as they reach *relativistic speeds. The accelerator is used with protons, deuterons, and alpha particles.

synchronous motor See electric motor.

synchronous orbit (geosynchronous orbit) An orbit of the earth made by an artiÜcial *satellite with a period exactly equal to the earth’s period of rotation on its axis, i.e. 23 hours 56 minutes 4.1 seconds. If the orbit is inclined to the equatorial plane the satellite will appear from the earth to trace out a Ügure-of-eight track once every 24 hours. If the orbit lies in the equatorial plane and is circular, the satellite will appear to be stationary. This is called a stationary orbit (or geostationary orbit) and it occurs at an altitude of 35 900 km. Most communication satellites are in stationary orbits, with three or more spaced round the orbit to give worldwide coverage.

synchronous rotation The rotation of a natural satellite in which the period of rotation is equal to its orbital period. The moon, for example, is in synchronous rotation about the earth and therefore always presents the same face to the earth.

synchrotron A particle accelerator used to impart energy to electrons and protons in order to carry out experiments in particle physics and in some cases to make use of the *synchrotron radiation produced.

The particles are accelerated in closed orbits (often circular) by radio-frequency Üelds. Magnets are spaced round the orbit to bend the trajectory of the particles and separate focusing magnets are used to keep the particles in a narrow beam. The radio-frequency accelerating cavities are interspersed between the magnets. The motion of the particles is automatically synchronized with the rising magnetic Üeld, as the Üeld strength has to increase as the particle energy increases; the fre-

quency of the accelerating Üeld also has to increase synchronously.

synchrotron radiation (magnetobremsstrahlung) Electromagnetic radiation that is emitted by charged particles moving at relativistic speeds in circular orbits in a magnetic Üeld. The rate of emission is inversely proportional to the product of the radius of curvature of the orbit and the fourth power of the mass of the particles. For this reason, synchrotron radiation is not a problem in the design of proton *synchrotrons but it is signiÜcant in electron synchrotrons. The greater the circumference of a synchrotron, the less important is the loss of energy by synchrotron radiation. In *storage rings, synchrotron radiation is the principal cause of energy loss.

However, since the 1950s it has been realized that synchrotron radiation is itself a very useful tool and many accelerator laboratories have research projects making use of the radiation on a secondary basis to the main high-energy research. The radiation used for these purposes is primarily in the ultraviolet and X-ray frequencies.

Much of the microwave radiation from |

|

|

celestial radio sources outside the Galaxy |

|

|

is believed to originate from electrons |

|

|

moving in curved paths in celestial mag- |

|

|

netic Üelds; it is also called synchrotron |

|

|

radiation as it is analogous to the radia- |

|

|

tion occurring in a synchrotron. |

|

|

syncline See fold. |

|

|

syncytium A group of animal cells in |

|

|

which cytoplasmic continuity is main- |

|

s |

|

||

|

|

|

tained. For example, the cells of striated |

|

|

muscle form a syncytium. In some syn- |

|

|

cytia the cells remain discrete but are |

|

|

joined together by cytoplasmic bridges. |

|

|

syndiotactic See polymer. |

|

|

synecology The study of ecology at the |

|

|

level of the *community. A synecological |

|

|

study aims to investigate the relationships |

|

|

between different species that form a |

|

|

community and their interactions with |

|

|

the surrounding environment. Synecology |

|

|

involves both *biotic and *abiotic factors. |

|

|

Compare autecology. |

|

|

synergism (summation) 1. The phe- |

|

|

nomenon in which the combined action |

|

|

syngamy |

800 |

of two substances (e.g. drugs or hormones) produces a greater effect than would be expected from adding the individual effects of each substance. 2. The combined action of one muscle (the synergist) with another (the agonist) in producing movement. Compare antagonism.

syngamy See fertilization.

synodic month (lunation) The interval between new *moons. It is equal to 29 days, 12 hours, and 44 minutes.

synodic period The mean time taken by any object in the solar system to move between successive returns to the same position, relative to the sun as seen from the earth. Since a planet is best observed at opposition the synodic period of a planet, S, is easier to measure than its *sidereal period, P. For inferior planets 1/S = 1/P – 1/E; for superior planets 1/S = 1/E – 1/P, where E is the sidereal period of the earth.

synoptic chart See synoptic meteorology.

synoptic meteorology The branch of meteorology concerned with the study and analysis of weather information that is obtained simultaneously over a large area. It is based on the analysis of the synoptic chart, which is built up from simultaneous observations at weather stations of such elements as wind speed and direction, air temperature, cloud cover, and air pressure over an area at a particular time. Synoptic meteorology is applied chieÛy to weather forecasting.

ssynovial membrane The membrane that lines the ligament surrounding a

freely movable joint (such as that at the hip or elbow). It secretes a Ûuid (synovial Ûuid) that lubricates the layers of cartilage forming the articulating surfaces of the joint.

synthesis The formation of chemical compounds from more simple compounds.

synthesis gas A mixture of two parts hydrogen and one part carbon monoxide

made from methane and steam heated under pressure. It is used in the manufacture of various organic chemicals, including hydrocarbons, methanol, and other alcohols. See also haber process.

synthetic Describing a substance that has been made artiÜcially; i.e. one that does not come from a natural source.

synthon See supramolecular chemistry.

syrinx The sound-producing organ of a bird, situated at the lower end of the trachea where it splits into the bronchi. It has a complex structure with a number of vibrating membranes.

systematics The study of the diversity of organisms and their natural relationships. It is sometimes used as a synonym for *taxonomy. The term biosystematics describes the experimental study of diversity, especially at the species level. Biosystematic methods include breeding experiments, biochemical work (known as chemosystematics), and cytotaxonomy.

See also molecular systematics.

Système International d’Unités See si units.

systemic circulation The part of the circulatory system of birds and mammals that transports oxygenated blood from the left ventricle of the heart to the tissues in the body and returns deoxygenated blood from the tissues to the right atrium of the heart. Compare pulmonary circulation. See double circulation.

systems software See applications software.

systole The phase of the heart beat during which the ventricles of the heart contract to force blood into the arteries.

Compare diastole. See blood pressure.

syzygy The situation that occurs when the sun, the moon (or a planet), and the earth are in a straight line. This occurs when the moon (or planet) is at *conjunction or *opposition.

T

2,4,5-T 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyethanoic acid): a synthetic *auxin formerly widely used as a herbicide and defoliant. It is now banned in many countries as it tends to become contaminated with the toxic chemical *dioxin.

tachometer An instrument for measuring angular speed, especially the number of revolutions made by a rotating shaft in unit time. Various types of instrument are used, including mechanical, electrical, and electronic devices. The widely used electrical-generator tachometer consists of a small generator in which the output voltage is a measure of the rate of rotation of the shaft that drives it.

tachyon A hypothetical particle that has a speed in excess of the *speed of light. According to electromagnetic theory, a charged particle travelling through a medium at a speed in excess of the speed of light in that medium emits *Cerenkov radiation. A charged tachyon would emit Cerenkov radiation even in a vacuum. No such particle has yet been detected. According to the special theory of *relativity, it is impossible to accelerate a particle up to the speed of light because its energy E, given by E = mc2/√(1 – v2/c2), would have to become inÜnite. The theory, however, does not forbid the existence of particles with v > c (where c is the speed of light). In such cases the expression in the brackets becomes negative and the energy would be imaginary.

tactic movement See taxis.

tactic polymer See polymer.

taiga A terrestrial *biome consisting mainly of evergreen coniferous forests (mainly pine, Ür, and spruce), which occurs across subarctic North America and Eurasia. In certain parts, such as northeastern Siberia, deciduous conifers and broadleaved trees, such as larch and birch, are dominant. Over most of the

taiga the ground is permanently frozen within about one metre of the surface, which prevents water from Ültering down to deeper levels in the soil. This means that bogs may form in depressions. For at least six months of the year temperatures are below freezing but there is a short growing season lasting 3–5 months. The soil in taiga areas is acidic and infertile. Compare tundra.

talc A white or pale-green mineral form of magnesium silicate, Mg3Si4O10(OH)2, crystallizing in the triclinic system. It forms as a secondary mineral by alteration of magnesium-rich olivines, pyroxenes, and amphiboles of ultrabasic rocks. It is soaplike to touch and very soft, having a hardness of 1 on the Mohs’ scale. Massive Üne-grained talc is known as soapstone or steatite. Talc in powdered form is used as a lubricant, as a Üller in paper, paints, and rubber, and in cosmetics, ceramics, and French chalk. It occurs chieÛy in the USA, Russia, France, and Japan.

Tamm, Igor See cerenkov, pavel.

tandem generator A type of particle generator, essentially consisting of a *Van de Graaff generator that maintains one electrode at a high positive potential; this electrode is placed between two earthed electrodes. Negative ions are accelerated from earth potential to the positively charged electrode, where surplus electrons are stripped from the ions to produce positive ions, which are accelerated again from the positive electrode back to earth. Thus the ions are accelerated twice over by a single high potential. This tandem arrangement enables energies up to 30 MeV to be achieved.

tangent 1. A line that touches a curve or a plane that touches a surface. 2. See trigonometric functions.

tangent galvanometer A type of galvanometer, now rarely used, in which a

tanh |

802 |

small magnetic needle is pivoted horizontally at the centre of a vertical coil that is adjusted to be parallel to the horizontal component of the earth’s magnetic Üeld. When a current I is passed through the coil, the needle is deÛected so that it makes an angle θ with its equilibrium position parallel to the earth’s Üeld. The value of I is given by I = (2Hrtanθ)/n, where H is the strength of the earth’s horizontal component of magnetizing force, r is the radius of the coil, and n is the number of turns in the coil. Although not now used for measuring current, the instrument provides a means of measuring the earth’s magnetizing force.

tanh See hyperbolic functions.

crystals of guanine, in the *choroid of the eye of many nocturnal vertebrates. It reÛects light back onto the retina, thus improving vision and causing the eyes to shine in the dark.

tapeworms See cestoda.

tap root See root.

tar Any of various black semisolid mixtures of hydrocarbons and free carbon, produced by destructive distillation of *coal or by *petroleum reÜning.

tarsal (tarsal bone) One of the bones that form the ankle (see tarsus) in terrestrial vertebrates.

tar sand See oil sand.

tannic acid A yellowish complex organic compound present in certain plants. It is used in dyeing as a mordant.

tannin One of a group of complex organic chemicals commonly found in leaves, unripe fruits, and the bark of trees. Their function is uncertain though the unpleasant taste may discourage grazing animals. Some tannins have commercial uses, notably in the production of leather and ink.

tantalum Symbol Ta. A heavy blue-grey metallic *transition element; a.n. 73; r.a.m. 180.948; r.d. 16.63; m.p. 2996°C; b.p. 5427°C. It is found with niobium in the ore columbite–tantalite (Fe,Mn)- (Ta,Nb)2O6. It is extracted by dissolving in hydroÛuoric acid, separating the tantalum and niobium Ûuorides to give K2TaF7, and reduction of this with sodium. The element contains the stable isotope tanta-

tlum–181 and the long-lived radioactive isotope tantalum–180 (0.012%; half-life >107 years). There are several other shortlived isotopes. The element is used in certain alloys and in electronic components. Tantalum parts are also used in surgery because of the unreactive nature of the metal (e.g. in pins to join bones). Chemically, the metal forms a passive oxide layer in air. It forms complexes in the +2,

+3, +4, and +5 oxidation states. Tantalum was identiÜed in 1802 by Anders Ekeberg (1767–1813) and Ürst isolated in 1820 by Jöns Berzelius.

tapetum A reÛecting layer, containing

tarsus The ankle (or corresponding part of the hindlimb) in terrestrial vertebrates, consisting of a number of small bones (tarsals). The number of tarsal bones varies with the species: humans, for example, have seven.

tartaric acid A white crystalline naturally occurring carboxylic acid, (CHOH)2(COOH)2; r.d. 1.8; m.p. 171–174°C. It can be obtained from tartar (potassium hydrogen tartrate) deposits from wine vats, and is used in baking powders and as a foodstuffs additive. The compound

is optically active (see optical activity). The systematic name is 2,3-dihydroxy- butanedioic acid.

tartrate A salt or ester of *tartaric acid.

tartrazine A food additive (E102) that gives foods a yellow colour. Tartrazine can cause a toxic response in the immune system and is banned in some countries.

taste 1. The sense that enables the Ûavour of different substances to be distinguished (see taste bud). 2. The Ûavour of a substance.

taste bud A small sense organ in most vertebrates, specialized for the detection of taste. In terrestrial animals taste buds are concentrated on the upper surface of the *tongue. They are sensitive to four types of taste: sweet, salt, bitter, or sour. The taste bud transmits information about a particular type of taste to the brain via nerve Übres. The four types of

803 |

t-distribution |

taste bud show distinct distribution patterns on the surface of the human tongue.

In Üshes, taste buds are distributed over the entire surface of the body and provide information about the surrounding water.

TATA box (Hogness box) A sequence of nucleotides that serves as the main recognition site for the attachment of RNA polymerase in the *promoter of eukaryotic genes. Located at around 25 nucleotides before the start of transcription, it consists of the seven-base *consensus sequence TATAAAA, and is analogous to the *Pribnow box in prokaryotic promoters.

Tatum, Edward See beadle, george wells.

tau particle See elementary particles; lepton.

tautomerism A type of *isomerism in which the two isomers (tautomers) are in equilibrium. See keto–enol tautomerism.

taxis (taxic response; tactic movement)

The movement of a cell (e.g. a gamete) or a microorganism in response to an external stimulus. Certain microorganisms have a light-sensitive region that enables them to move towards or away from high light intensities (positive and negative *phototaxis respectively). Many bacteria move in response to chemical stimuli (chemotaxis); a speciÜc example is aerotaxis, in which atmospheric oxygen is the stimulus. Taxic responses are restricted to cells that possess cilia, Ûagella, or some other means of locomotion. The term is usually not applied to the movements of higher animals. Compare kinesis; tropism.

taxon (pl. taxa) Any named taxonomic group of any *rank in the hierarchical *classiÜcation of organisms. Thus the taxa Papilionidae, Lepidoptera, Hexapoda, and Uniramia are named examples of a family, order, class, and phylum, respectively.

taxonomy The study of the theory, practice, and rules of *classiÜcation of living and extinct organisms. The naming, description, and classiÜcation of a given organism draws on evidence from a number of Üelds. Classical taxonomy is based on morphology and anatomy. Cytotaxonomy compares the size, shape, and number of chromosomes of different or-

ganisms. Numerical taxonomy uses mathematical procedures to assess similarities and differences and establish taxonomic groups. See also systematics.

Taylor series The inÜnite power series of derivatives into which a function f(x) can be expanded, for a Üxed value of the variable x = a:

f(x) = f(a) + f′(a)(x – a) + f″(a)(x – a)2/2! + …

When a = 0, the series formed is known as Maclaurin’s series:

f(x) = f(0) + f′(0)x + f″(0)x2/2! + …

The series was discovered by Brook Taylor (1685–1731) and the special case was named after Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746).

TCA cycle See krebs cycle.

T cell (T lymphocyte) Any of a population of *lymphocytes that are the principal agents of cell-mediated *immunity. T cells are derived from the bone marrow but migrate to the thymus to mature (hence T cell). Subpopulations of T cells play different roles in the immune response and can be characterized by their surface antigens (see cd). Helper T cells recognize foreign antigens provided these are presented by inducer cells (such as macrophages and B lymphocytes) bearing class II *histocompatibility antigens. The helper T cell carries T-cell receptors, which recognize the class II antigens on the inducer cell. Interleukin-1 released by inducer cells stimulates helper T cells to release inter- leukin-2, which in turn triggers the release of other cytokines (see interleukin). Consequently there is a proliferation of B lymphocytes and the generation of effec-

tor T cells, i.e. cytotoxic T cells, delayed t hypersensitivity T cells, and suppressor T

cells.

Cytotoxic T cells recognize foreign antigen on the surface of virus-infected cells and destroy the cell by releasing cytolytic proteins. Suppressor T cells are important in regulating the activity of other lymphocytes and are crucial in maintaining tolerance to self tissues. Delayed hypersensitivity T cells mediate delayed hypersensitivity by releasing various *lymphokines.

t-distribution In *statistics, a probability distribution made up of the means (see

tebi- |

804 |

average) of random samples from a collection of samples that have a *normal distribution of unknown *variance. See also normal distribution; poisson distribution.

tebi- See binary prefixes.

technetium Symbol Tc. A radioactive metallic *transition element; a.n. 43; m.p. 2172°C; b.p. 4877°C. The element can be detected in certain stars and is present in the Üssion products of uranium. It was Ürst made by Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè (1905–89) by bombarding molybdenum with deuterons to give tech- netium–97. The most stable isotope is technetium–99 (half-life 2.6 × 106 years); this is used to some extent in labelling for medical diagnosis. There are sixteen known isotopes. Chemically, the metal has properties intermediate between manganese and rhenium.

technicolour theory See higgs field.

teeth See deciduous teeth; permanent teeth; dentition; tooth.

television The transmission and reception of moving images by means of radio waves or cable. The scene to be transmitted is focused onto a photoelectric screen in the television *camera. This screen is scanned by an electron beam. The camera produces an electric current, the instantaneous magnitude of which is proportional to the brightness of the portion of the screen being scanned. In Europe the screen is scanned by 625 lines and 25 such frames are produced every second. In the USA 525 lines and 30 frames per second are used. The picture signal so produced is used to modulate a VHF or UHF carrier wave and is transmitted with an independent sound signal, but with colour information (if any) incorporated into the brief gaps between the picture lines. The signals received by the receiving aerial are demodulated in the receiver; the demodulated picture signal controls the electron beam in a cathode-ray tube, on the screen of which the picture is reconstructed. See also colour television.

television tube See cathode rays.

TeÛon Trade name for a form of *polytetraÛuoroethene.

tektite A small black, greenish, or yellowish glassy object found in groups on the earth’s surface and consisting of a silicaceous material unrelated to the geological formations in which it is found. Tektites are believed to have formed on earth as a result of the impact of meteorites.

telecommunications The study and application of means of transmitting information, either by wires or by electro-

tmagnetic radiation.

Teleostei The major superorder of the *Osteichthyes (bony Üsh), containing about 20 000 species. Teleosts have colonized an extensive variety of habitats and show great diversity of form. The group includes the eel, seahorse, plaice, and

salmon. They have been the dominant Üsh since the Cretaceous period (about 70 million years ago).

telescope An instrument that collects radiation from a distant object in order to produce an image of it or enable the radiation to be analysed. See Feature.

tellurides Binary compounds of tellurium with other more electropositive elements. Compounds of tellurium with nonmetals are covalent (e.g. H2Te). Metal tellurides can be made by direct combination of the elements and are ionic (containing Te2–) or nonstoichiometric interstitial compounds (e.g. Pd4Te, PdTe2).

tellurium Symbol Te. A silvery metalloid element belonging to *group 16 (formerly VIB) of the periodic table; a.n. 52; r.a.m. 127.60; r.d. 6.24 (crystalline); m.p. 449.5°C; b.p. 989.8°C. It occurs mainly as *tellurides in ores of gold, silver, copper, and nickel and it is obtained as a byproduct in copper reÜning. There are eight natural isotopes and nine radioactive isotopes. The element is used in semiconductors and small amounts are added to certain steels. Tellurium is also added in small quantities to lead. Its chemistry is similar to that of sulphur. It was discovered by Franz Müller (1740–1825) in 1782.

telomere The end of a chromosome, which consists of tandemly repeated short sequences of DNA that perform the function of ensuring that each cycle of *DNA replication has been completed.

805

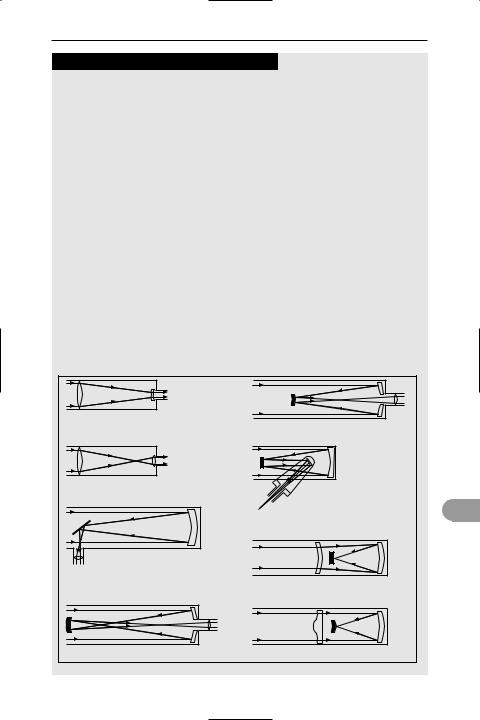

OPTICAL ASTRONOMICAL TELESCOPES

Optical astronomical telescopes fall into two main classes: refracting telescopes (or refractors), which use lenses to form the primary image, and reflecting telescopes (or reflectors), which use mirrors.

Refracting telescopes

The refracting telescopes use a converging lens to collect the light and the resulting image is magniÜed by the eyepiece. This type of instrument was Ürst constructed in 1608 by Hans Lippershey (1587–1619) in Holland and developed in the following year as an astronomical instrument by Galileo, who used a diverging lens as eyepiece. The Galilean telescope was later improved by Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), who substituted a converging eyepiece lens. This form is still in use for small astronomical telescopes (the Keplerian telescope).

Reflecting telescopes

The Ürst reÛecting telescope was produced by Newton in 1668. This used a concave mirror to collect and focus the light and a small secondary mirror at an angle of 45° to the main beam to reÛect the light into the magnifying eyepiece. This design is known as the Newtonian telescope. The Gregorian telescope, designed by James Gregory (1638–75), and the Cassegrainian telescope, designed by N. Cassegrain (Û. 1670s), use different secondary optical systems. The coudé telescope (French: angled) is sometimes used with larger instruments as it increases their focal lengths.

Catadioptic telescopes

Catadioptic telescopes use both lenses and mirrors. The most widely used astronomical instruments in this class are the Maksutov telescope and the

Schmidt camera.

(a) Galilean |

(e) Cassegrain |

|

|

(b) Keplerian |

|

|

t |

|

(f) Coudé |

(c) Newtonian |

|

|

(g) Maksutov |

(d) Gregorian |

(h) Schmidt |