A Dictionary of Science

.pdf

saprotroph |

726 |

*corundum except ruby, especially the blue variety, but other colours of sapphire include yellow, brown, green, pink, orange, and purple. Sapphires are obtained from igneous and metamorphic rocks and from alluvial deposits. The chief sources are Sri Lanka, Kashmir, Burma, Thailand, East Africa, the USA, and Australia. Sapphires are used as gemstones and in record-player styluses and some types of laser. They are synthesized by the Verneuil Ûame-fusion process.

saprotroph (saprobe; saprobiont) Any organism that feeds by absorbing dead organic matter. Most saprotrophs are bacteria and fungi. Saprotrophs are important in *food chains as they bring about decay and release nutrients for plant growth. Compare parasitism.

sapwood (alburnum) The outer wood of a tree trunk or branch. It consists of living *xylem cells, which both conduct water and provide structural support. Compare

heartwood.

sarcoma See cancer.

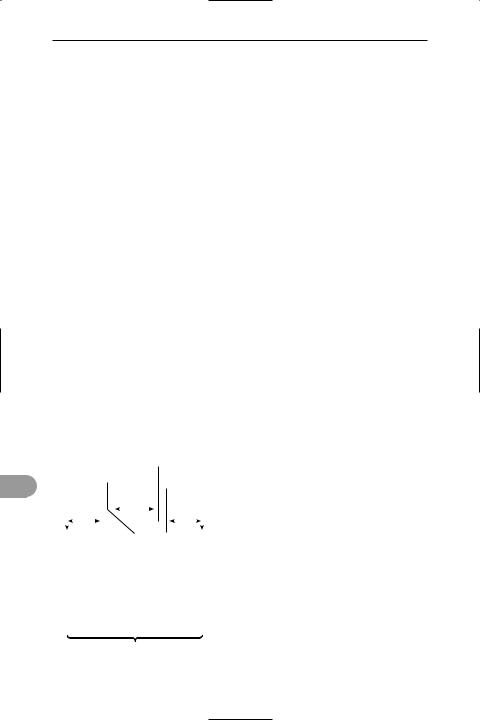

sarcomere Any of the functional units that make up the myoÜbrils of *voluntary muscle. Each sarcomere is bounded by two membranes (Z lines), which provide the points of attachment of *actin Ülaments; another membrane (the M band or line) is the point of attachment of the *myosin Ülaments. The sarcomere is di-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

thick (myosin) |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

filament |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

M band |

|

|

|

thin (actin) |

|||||||

|

s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

filament |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Z line |

H |

|

|

|

Z line |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

I band |

band |

|

|

|

I band |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sarcomere

Structure of a sarcomere

vided into various bands reÛecting the arrangement of the Ülaments (see illustration). During muscle contraction the actin and myosin Ülaments slide over each other and the length of the sarcomere shortens: the Z lines are drawn closer together and the I and H bands become narrower.

satellite 1. (natural satellite) A relatively small natural body that orbits a planet. For example, the earth’s only natural satellite is the moon. 2. (artiÜcial satellite) A man-made spacecraft that orbits the earth, moon, sun, or a planet. ArtiÜcial satellites are used for a variety of purposes. Communication satellites are used for relaying telephone, radio, and television signals round the curved surface of the earth (see synchronous orbit). They are of two types: passive satellites reÛect signals from one point on the earth’s surface to another; active satellites are able to amplify and retransmit the signals that they pick up. Astronomical satellites are equipped to gather and transmit to earth astronomical information from space, including conditions in the earth’s atmosphere, which is of great value in weather forecasting.

satellite DNA See repetitive dna.

saturated 1. (of a solution) Containing the maximum equilibrium amount of solute at a given temperature. In a saturated solution the dissolved substance is in equilibrium with undissolved substance; i.e. the rate at which solute particles leave the solution is exactly balanced by the rate at which they dissolve. A solution containing less than the equilibrium amount is said to be unsaturated. One containing more than the equilibrium amount is supersaturated. Supersaturated solutions can be made by slowly cooling a saturated solution. Such solutions are metastable; if a small crystal seed is added the excess solute crystallizes out of solution. 2. (of a vapour) See vapour pressure. 3. (of a ferromagnetic material) Unable to be magnetized more strongly as all the domains are orientated in the direction of the Üeld. 4. (of a compound) Consisting of molecules that have only single bonds (i.e. no double or triple bonds). Saturated compounds can un-

727 |

scales |

dergo substitution reactions but not addition reactions. Compare unsaturated.

saturation 1. See colour. 2. See supersaturation.

Saturn A planet having its orbit between those of Jupiter and Uranus. Its mean distance from the sun is 1426.72 × 106 km and its equatorial diameter

120 536 km; it has a sidereal period of

29.42 years. Although it is the second largest planet its mean density is lower than any other, its relative density being 0.7. It has at least 34 satellites, of which the largest, Titan, is the only planetary satellite to have a dense atmosphere. Saturn is believed to consist of a dense rocky core, surrounded by hydrogen compressed to such an extent that it behaves like a metal; this layer merges with an atmosphere of hydrogen. The planet is best known for the system of rings that surrounds it in an equatorial plane; the rings have an overall diameter of about 273 000 km. They are believed to consist of millions of particles of ice (possibly with a rock core) with diameters between <1 mm and 10 m. Saturn was given a preliminary examination by the satellite Pioneer II in 1979 and more detailed studies by Voyager I in 1980 and Voyager II in 1981.

savanna See grassland.

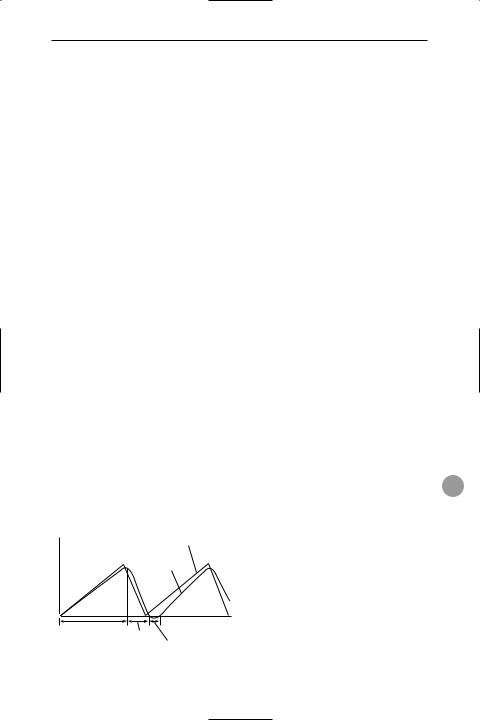

sawtooth waveform A waveform in which the variable increases uniformly with time for a Üxed period, drops sharply to its initial value, and then repeats the sequence periodically. The illustration shows the ideal waveform and the waveform generated by practical electrical circuits. Sawtooth generators are frequently used to provide a time base for electronic

V |

|

ideal waveform |

|

|

actual |

|

|

waveform |

|

active interval |

t |

|

flyback |

|

|

|

inactive interval

Sawtooth waveform

circuits, as in the *cathode-ray oscilloscope.

s-block elements The elements of the Ürst two groups of the *periodic table; i.e. groups 1 (Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs, Fr) and 2 (Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Ra). The outer electronic conÜgurations of these elements all have inert-gas structures plus outer ns1 (group 1) or ns2 (group 2) electrons. The term thus excludes elements with incomplete inner d-levels (transition metals) or with incomplete inner f-levels (lanthanoids and actinoids) even though these often have outer ns2 or occasionally ns1 conÜgurations. Typically, the s-block elements are reactive metals forming stable ionic compounds containing M+ or M2+ ions. See alkali metals; alkaline-earth metals.

scalar product (dot product) The product of two vectors U and V, with compo-

nents U1, U2, U3 and V1, V2, V3, respectively, given by:

U.V = U1V1 + U2V2 + U3V3.

It can also be written as UVcosθ, where U |

|

|

and V are the lengths of U and V, respec- |

|

|

tively, and θ is the angle between them. |

|

|

Compare vector product. |

|

|

scalar quantity A quantity in which di- |

|

|

rection is either not applicable (as in tem- |

|

|

perature) or not speciÜed (as in speed). |

|

|

Compare vector. |

|

|

scalar triple product See triple prod- |

|

|

uct. |

|

|

scalene Denoting a triangle having |

|

|

three unequal sides. |

|

|

scaler (scaling circuit) An electronic |

s |

|

counting circuit that provides an output |

|

|

when it has been activated by a pre- |

|

|

scribed number of input pulses. A decade |

|

|

scaler produces an output pulse when it |

|

|

has received ten or a multiple of ten input |

|

|

pulses; a binary scaler produces its output |

|

|

after two input pulses. |

|

|

scales The small bony or horny plates |

|

|

forming the body covering of Üsh and rep- |

|

|

tiles. The wings of some insects, notably |

|

|

the Lepidoptera (butterÛies and moths), |

|

|

are covered with tiny scales that are |

|

|

modiÜed cuticular hairs. |

|

|

In Üsh there are three types of scales. |

|

|

Placoid scales (denticles), characteristic of |

|

|

scandium |

728 |

cartilaginous Üsh, are small and toothlike, with a projecting spine and a Ûattened base embedded in the skin. They are made of *dentine, have a pulp cavity, and the spine is covered with a layer of enamel. Teeth are probably modiÜed placoid scales. Cosmoid scales, characteristic of lungÜsh and coelacanths, have an outer layer of hard cosmin (similar to dentine)

covered by modiÜed enamel (ganoine) and inner layers of bone. The scale grows by adding to the inner layer only. In modern lungÜsh the scales are reduced to large bony plates. Ganoid scales are characteristic of primitive ray-Ünned Üshes, such as sturgeons. They are similar to cosmoid scales but have a much thicker layer of ganoine and grow by the addition of material all round. The scales of modern teleost Üsh are reduced to thin bony plates.

In reptiles there are two types of scales: horny epidermal corneoscutes sometimes fused with underlying bony dermal osteoscutes.

scandium Symbol Sc. A rare soft silvery metallic element belonging to group 3 (formerly IIIA) of the periodic table; a.n. 21; r.a.m. 44.956; r.d. 2.989 (alpha form), 3.19 (beta form); m.p. 1541°C; b.p. 2831°C. Scandium often occurs in *lanthanoid ores, from which it can be separated on account of the greater solubility of its thiocyanate in ether. The only natural isotope, which is not radioactive, is scan- dium–45, and there are nine radioactive isotopes, all with relatively short half-

slives. Because of the metal’s high reactivity and high cost no substantial uses have been found for either the metal or its compounds. Predicted in 1869 by Dmitri Mendeleev, and then called ekaboron, the oxide (called scandia) was isolated by Lars Nilson (1840–99) in 1879.

scanning The process of repeatedly crossing a surface or volume with a beam, aerial, or moving detector in order to bring about some change to the surface or

volume, to measure some activity, or to detect some object. The Ûuorescent screen of a television picture tube is scanned by an electron beam in order to produce

the picture; an area of the sky may be scanned by the movable dish aerial of a

radio telescope in order to detect celestial bodies, etc.

scanning electron microscope See

electron microscope.

scanning tunnelling microscope

(STM) A type of microscope in which a Üne conducting probe is held close to the surface of a sample. Electrons tunnel between the sample and the probe, producing an electrical signal. The probe is slowly moved across the surface and raised and lowered so as to keep the signal constant. A proÜle of the surface is produced, and a computer-generated contour map of the surface is produced. The technique is capable of resolving individual atoms, but works better with conducting materials. See also atomic force microscope.

scapula (shoulder blade) The largest of the bones that make up each half of the *pectoral (shoulder) girdle. It is a Ûat triangular bone, providing anchorage for the muscles of the forelimb and an articulation for the *humerus at the *glenoid cavity. It is joined to the *clavicle (collar bone) in front.

scattering of electromagnetic radiation The process in which electromagnetic radiation is deÛected by particles in the matter through which it passes. In elastic scattering the photons of the radiation are reÛected; i.e. they bounce off the atoms and molecules without any change of energy. In this type of scattering, known as Rayleigh scattering (after Lord Rayleigh; 1842–1919), there is a change of phase but no frequency change. In inelastic scattering and superelastic scattering, there is interchange of energy between the photons and the particles. Consequently, the scattered photons have a different wavelength as well as a different phase. Examples include the *Raman effect and the *Compton effect. See also tyn-

dall effect.

scavenger An animal that feeds on dead organic matter. Scavengers (such as hyenas) may feed on animals killed by predators or they may be *detritivores.

Scheele, Karl Wilhelm (1742–86) Swedish chemist, who became an apothecary and in 1775 set up his own pharmacy

729 |

Schrödinger, Erwin |

at Köping. He made many chemical discoveries. In 1772 he prepared oxygen (see also lavoisier, antoine; priestley, joseph) and in 1774 he isolated chlorine. He also discovered manganese, glycerol, hydrocyanic (prussic) acid, citric acid, and many other substances.

scheelite A mineral form of calcium tungstate, CaWO4, used as an ore of tungsten. It occurs in contact metamorphosed deposits and vein deposits as colourless or white tetragonal crystals.

Schiaparelli, Giovanni Virginio

(1835–1910) Italian astronomer, who became director of the Milan Observatory in 1860. There he studied asteroids, meteors, and planets. In 1877 he described canali among the surface features of *Mars. The Italian word (which means ‘channels’) was mistranslated as ‘canals’, establishing a long controversy about the possibility of intelligent life on Mars.

Schiff’s base A compound formed by a condensation reaction between an aromatic amine and an aldehyde or ketone, for example

RNH2 + R′CHO → RN:CHR′ + H2O

The compounds are often crystalline and are used in organic chemistry for characterizing aromatic amines (by preparing the Schiff’s base and measuring the melting point). They are named after the German chemist Hugo Schiff (1834–1915).

Schiff’s reagent A reagent used for testing for aldehydes and ketones; it consists of a solution of fuchsin dye that has been decolorized by sulphur dioxide. Aliphatic aldehydes restore the pink immediately, whereas aromatic ketones have no effect on the reagent. Aromatic aldehydes and aliphatic ketones restore the colour slowly.

schist A group of coarse-grained metamorphic rocks characterized by the presence of platy minerals (e.g. micas, chlorite, talc, hornblende, and graphite) that show parallel alignment at right angles to the direction of stress. The original bedding of the rock is absent. Schists readily split into layers along schistosity planes, parallel to the alignment of the minerals.

schizocarp A dry indehiscent fruit formed from carpels that develop into separate one-seeded fragments called mericarps, which may be dehiscent, as in the *regma, or indehiscent, as in the *cremocarp and *carcerulus.

schizogeny The localized separation of plant cells to form a cavity (surrounded by the intact cells) in which secretions accumulate. Examples are the resin canals of some conifers and the oil ducts of caraway and aniseed fruits. Compare lysigeny.

Schleiden, Matthias Jakob See cell theory; schwann, theodor.

schlieren photography A technique that enables density differences in a moving Ûuid to be photographed. In the turbulent Ûow of a Ûuid, for example, short-lived localized differences in density create differences of refractive index, which show up on photographs taken by short Ûashes of light as streaks (German: Schliere). Schlieren photography is used in wind-tunnel studies to show the density gradients created by turbulence and the shock waves around a stationary model.

Schmidt camera See telescope.

schönite A mineral form of potassium sulphate, K2SO4.

Schottky defect See crystal defect.

Schottky effect A reduction in the *work function of a substance when an external accelerating electric Üeld is applied to its surface in a vacuum. The Üeld

reduces the potential energy of electrons s outside the substance, distorting the po-

tential barrier at the surface and causing *Üeld emission. A similar effect occurs when a metal surface is in contact with a *semiconductor rather than a vacuum, when it is known as a Schottky barrier. The effect was discovered by the German physicist Walter Schottky (1886–1976).

Schrieffer, John See bardeen, john.

Schrödinger, Erwin (1887–1961) Austrian physicist, who became professor of physics at Berlin University in 1927. He left for Oxford to escape the Nazis in 1933, returned to Graz in Austria in 1936, and then left again in 1938 for Dublin’s

Schrödinger equation |

730 |

Institute of Advanced Studies. He Ünally returned to Austria in 1956. He is best known for the development of *wave mechanics and the *Schrödinger equation, work that earned him a share of the 1933 Nobel Prize for physics with Paul Dirac (1902–84).

Schrödinger equation An equation used in wave mechanics (see quantum mechanics) for the wave function of a particle. The time-independent Schrödinger equation is:

2ψ + 8π2m(E – U)ψ/h2 = 0

where ψ is the wave function, 2 the Laplace operator (see laplace equation), h the Planck constant, m the particle’s mass, E its total energy, and U its potential energy. The equation can be solved exactly for simple systems, such as the harmonic oscillator and the hydrogen atom. It was devised by Erwin Schrödinger, who was mainly responsible for wave mechanics.

Schrödinger’s cat A thought experiment introduced by Erwin Schrïdinger in 1935 to illustrate the paradox in *quantum mechanics regarding the probability of Ünding, say, a subatomic particle at a speciÜc point in space. According to Niels Bohr, the position of such a particle remains indeterminate until it has been observed. Schrödinger postulated a sealed vessel containing a live cat and a device triggered by a quantum event, such as the radioactive decay of a nucleus. If the quantum event occurs, cyanide is released and the cat dies; if the event does not occur the cat lives. Schrödinger argued

s that Bohr’s interpretation of events in quantum mechanics means that the cat could only be said to be alive or dead when the vessel has been opened and the situation inside it had been observed.

Wigner’s friend is a variation of the Schrödinger’s cat paradox in which a friend of the physicist Eugene Wigner is the Ürst to look inside the vessel. The friend will either Ünd a live or dead cat. However, if Professor Wigner has both the vessel with the cat and the friend in a closed room, the state of mind of the friend (happy if there is a live cat but sad if there is a dead cat) cannot be determined in Bohr’s interpretation of quantum mechanics until the professor has

looked into the room although the friend has looked at the cat. This paradox has been extensively discussed since its introduction with many proposals made to resolve it. It is thought that the explanation depends on *decoherence.

Schwann, Theodor (1810–82) German physiologist, who trained in medicine. After working in Berlin, he moved to Belgium. In 1838 the German botanist Matthias Schleiden (1804–81) had stated that plant tissues were composed of cells. Schwann demonstrated the same fact for animal tissues, and in 1839 concluded that all tissues are made up of cells: this laid the foundations for the *cell theory. Schwann also worked on fermentation and discovered the enzyme *pepsin. *Schwann cells are named after him.

Schwann cell A cell that forms the *myelin sheath of nerve Übres (axons). Each cell is responsible for a given length of a particular axon (called an internode); adjacent internodes are separated by small gaps (nodes of Ranvier) where the axon is bare. During its development the cell wraps itself around the Übre, so the sheath consists of concentric layers of Schwann cell membrane. These cells are named after Theodor Schwann.

Schwarzschild radius A critical radius of a body of given mass that must be exceeded if light is to escape from that body. It equals 2GM/c2, where G is the gravitational constant, c is the speed of light, and M is the mass of the body. If the body collapses to such an extent that its radius is less than the Schwarzschild radius the escape velocity becomes equal to the speed of light and the object becomes a *black hole. The Schwarzschild radius is then the radius of the hole’s event horizon. It is named after Karl Schwarzschild (1873– 1916).

Schweizer’s reagent A solution made by dissolving copper(II) hydroxide in concentrated ammonia solution. It has a deep blue colour and is used as a solvent for cellulose in the cuprammonium process for making rayon. When the cellulose solution is forced through spinnarets into an acid bath, Übres of cellulose are reformed.

731 |

seamount |

scientiÜc notation See standard form.

scintillation counter A type of particle or radiation counter that makes use of the Ûash of light (scintillation) emitted by an excited atom falling back to its ground state after having been excited by a passing photon or particle. The scintillating medium is usually either solid or liquid and is used in connection with a *photomultiplier, which produces a pulse of current for each scintillation. The pulses are counted with a *scaler. In certain cases, a pulse-height analyser can be used to give an energy spectrum of the incident radiation.

scintillator See phosphor.

scion See graft.

sclera See sclerotic.

sclerenchyma A plant tissue whose cell walls have become impregnated with lignin. Due to the added strength that this confers, sclerenchyma plays an important role in support; it is found in the stems and also in the midribs of leaves. Mature sclerenchyma cells are dead, since the lignin makes the cell wall impermeable to water and gases. The presence of *plasmodesmata prevents lignin being deposited in areas of the cell wall called pits; these form shallow depressions enabling the exchange of substances between adjacent cells. Compare collenchyma (see ground tissues); parenchyma.

sclerometer A device for measuring the hardness of a material by determining the pressure on a standard point that is required to scratch it or by determining the height to which a standard ball will rebound from it when dropped from a Üxed height. The rebound type is sometimes called a scleroscope.

scleroprotein Any of a group of proteins found in the exoskeletons of some invertebrates, notably insects. Scleroproteins are formed by conversion of the relatively soft elastic larval protein by a natural tanning process (sclerotization) involving orthoquinones. These are secreted and form cross linkages between polypeptides of the proteins, producing a hard rigid covering.

sclerotic (sclera) The tough external layer of the vertebrate eye. At the front of the eye, the sclera is modiÜed to form the *cornea.

scorpions See arachnida.

scotopic vision The type of vision that occurs when the *rods in the eye are the principal receptors, i.e. when the level of illumination is low. With scotopic vision colours cannot be identiÜed. Compare photopic vision.

SCP See single-cell protein.

screen grid A wire grid in a tetrode or pentode *thermionic valve, placed between the anode and the *control grid to reduce the grid–anode capacitance. See also suppressor grid.

screw 1. A simple *machine effectively consisting of an inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder. The mechanical advantage of a screw is 2πr/p, where r is the radius of the thread and p is the pitch, i.e. the distance between adjacent threads of the screw measured parallel to its axis.

2. A symmetry element in a crystal lattice that consists of a combination of a rotation and a translation. See also glide.

scrotum The sac of skin and tissue that contains and supports the *testes in most mammals. It is situated outside the body cavity and allows sperm to develop at the optimum temperature, which is slightly lower than body temperature.

scurvy A disease caused by deÜciency of *vitamin C, which results in poor colla-

gen formation. Symptoms include s anaemia, skin discoloration, and tooth

loss. Scurvy was a common disease among sailors in the 16th–18th centuries, when no fresh food was available on long sea voyages.

S-drop See strange matter.

seaborgium Symbol Sg. A radioactive *transactinide element; a.n. 106. It was Ürst detected in 1974 by Albert Ghiorso and a team in California. It can be produced by bombarding californium–249 nuclei with oxygen–18 nuclei. It is named after the US physicist Glenn Seaborg (1912–99).

seamount An isolated steep-sided hill

search coil |

732 |

up to 1000 m tall on the sea Ûoor. Most are conical in shape and volcanic in origin, with summits 1000–2000 m below the sea surface. See also guyot.

search coil A small coil in which a current can be induced to detect and measure a magnetic Üeld. It is used in conjunction with a *Ûuxmeter.

Searle’s bar An apparatus for determining the thermal conductivity of a bar of material. The bar is lagged and one end is heated while the other end is cooled, by steam and cold water respectively. At two points d apart along the length of the bar the temperature is measured using a thermometer or thermocouple. The conductivity can then be calculated from the measured temperature gradient.

seaweeds Large multicellular *algae living in the sea or in the intertidal zone. They are commonly species of the *Chlorophyta, *Phaeophyta, and *Rhodophyta.

sebaceous gland A small gland occurring in mammalian *skin. Its duct opens into a hair follicle, through which it discharges *sebum onto the skin surface.

sebum The substance secreted by *sebaceous glands onto the surface of the *skin. It is a fatty mildly antiseptic material that protects, lubricates, and waterproofs the skin and hair and helps prevent desiccation.

secant 1. See trigonometric functions.

s2. A line that cuts a circle or other curve. sech See hyperbolic functions.

second 1. Symbol s. The SI unit of time equal to the duration of 9 192 631 770 pe-

riods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between two hyperÜne lev-

els of the ground state of the caesium–133 atom. 2. Symbol ″. A unit of angle equal to 1/3600 of a degree or 1/60 of a minute.

secondary alcohol See alcohols. secondary amine See amines.

secondary cell A *voltaic cell in which the chemical reaction producing the e.m.f. is reversible and the cell can therefore be charged by passing a current

through it. See accumulator; intercalation cell. Compare primary cell.

secondary colour Any colour that can be obtained by mixing two *primary colours. For example, if beams of red light and green light are made to overlap, the secondary colour, yellow, will be formed. Secondary colours of light are sometimes referred to as the pigmentary primary colours. For example, if transparent yellow and magenta pigments are overlapped in white light, red will be observed. In this case the red is a pigmentary secondary although it is a primary colour of light.

secondary consumer See consumer.

secondary emission The emission of electrons from a surface as a result of the impact of other charged particles, especially as a result of bombardment with (primary) electrons. As the number of secondary electrons can exceed the number of primary electrons, the process is important in *photomultipliers. See also auger effect.

secondary growth (secondary thickening) The increase in thickness of plant shoots and roots through the activities of the vascular *cambium and *cork cambium. It is seen in most dicotyledons and gymnosperms but not in monocotyledons. The tissues produced by secondary growth are called secondary tissues and the resultant plant or plant part is the secondary plant body. Compare primary growth.

secondary sexual characteristics External features of a sexually mature animal that, although not directly involved in copulation, are signiÜcant in reproductive behaviour. The development of such features is controlled by sex hormones (androgens or oestrogens); they may be seasonal (e.g. the antlers of male deer or the body colour of male sticklebacks) or permanent (e.g. breasts in women or facial hair in men). In humans they develop during *adolescence.

secondary structure See protein. secondary thickening See secondary

growth.

secondary winding The winding on

733 |

Seebeck effect |

the output side of a *transformer or *induction coil. Compare primary winding.

second convoluted tubule See distal

convoluted tubule.

second messenger A chemical within a cell that is responsible for initiating the response to a signal from a chemical messenger (such as a hormone, neurotransmitter, or growth factor) that cannot enter the target cell itself, for example because it is not lipid-soluble and is therefore unable to cross the plasma membrane. A common second messenger is *cyclic AMP; the signal for its formation within the cell is transmitted from hormone receptors on the cell surface by *G protein.

second-order reaction See order.

secretin A hormone produced by the anterior part of the small intestine (the *duodenum and *jejunum) in response to the presence of hydrochloric acid from the stomach. It causes the pancreas to secrete alkaline pancreatic juice and stimulates bile production in the liver. Secretin, whose function was Ürst demonstrated in 1902, was the Ürst substance to be described as a hormone.

secretion 1. The manufacture and discharge of speciÜc substances into the external medium by cells in living organisms. (The substance secreted is also called the secretion.) Secretory cells are often specialized and organized in groups to form *glands. The substances produced may be released directly into the blood (endocrine secretion; see endocrine gland) or through a duct (exocrine secretion; see exocrine gland). Secretions can be classiÜed according to the manner of their discharge. Merocrine (eccrine) secretion occurs without the secretory cells sustaining any permanent change; in apocrine secretion the cells release a secretory vesicle incorporating part of the secretory cell membrane; and holocrine secretion involves the disruption of the entire cell to release its accumulated secretory vesicles. 2. The process by which a substance is pumped out of a cell against a concentration gradient. Secretion has an important role in adjusting

the composition of urine as it passes through the *nephrons of the kidney.

secular magnetic variation See geomagnetism.

sedimentary rocks A group of rocks formed as a result of the accumulation and consolidation of sediments. Sedimentary rocks are one of the three major rock groups forming the earth’s crust (see also

igneous rocks; metamorphic rocks). Most sedimentary rocks are formed from pre-existing rocks that have been broken down through mechanical processes into small particles, which have then been transported and redeposited; these form the clastic sedimentary rocks. The clastic rocks are subdivided according to the size of the dominant constituent particles: arenaceous being composed largely of sand-grade particles (e.g. sandstone, grit), argillaceous of siltor clay-grade (e.g. mud, mudstone, clay, shale), and rudaceous of gravel-grade or larger particles (e.g. conglomerate). Chemical sedimentary rocks form the second large division of sedimentary rocks and originate as chemical precipitates at the site of deposition. These include the evaporites and sedimentary iron ores, and the organic sedimentary rocks, which are derived largely from the remains of plants and animals and include coal and many limestones.

sedimentation The settling of the solid particles through a liquid either to produce a concentrated slurry from a dilute suspension or to clarify a liquid containing solid particles. Usually this relies on

the force of gravity, but if the particles are s too small or the difference in density be-

tween the solid and liquid phases is too small, a *centrifuge may be used. In the simplest case the rate of sedimentation is determined by *Stokes’ law, but in practice the predicted rate is rarely reached. Measurement of the rate of sedimentation in an *ultracentrifuge can be used to estimate the size of macromolecules.

Seebeck effect (thermoelectric effect)

The generation of an e.m.f. in a circuit containing two different metals or semiconductors, when the junctions between the two are maintained at different temperatures. The magnitude of the e.m.f. depends on the nature of the metals and the

seed |

734 |

difference in temperature. The Seebeck effect is the basis of the *thermocouple. It was named after Thomas Seebeck (1770– 1831), who actually found that a magnetic Üeld surrounded a circuit consisting of two metal conductors only if the junctions between the metals were maintained at different temperatures. He wrongly assumed that the conductors were magnetized directly by the temperature difference. Compare peltier effect.

seed 1. (in botany) The structure in angiosperms and gymnosperms that develops from the ovule after fertilization.

Occasionally seeds may develop without fertilization taking place (see apomixis). The seed contains the *embryo and nutritive tissue, either as *endosperm or food stored in the *cotyledons. Angiosperm seeds are contained within a *fruit that develops from the ovary wall. Gymnosperm seeds lack an enclosing fruit and are thus termed naked. The seed is covered by a protective layer, the *testa. During development of the testa the seed dries out and enters a resting phase (dormancy) until conditions are suitable for germination.

Annual plants survive the winter or dry season as seeds. The evolution of the seed habit enabled plants to colonize the land, since seed plants do not depend on water for fertilization (unlike the lower plants). 2. (in chemistry) A crystal used to induce other crystals to form from a gas, liquid, or solution.

seed coat See testa.

sseed ferns See cycadofilicales. seed leaf See cotyledon.

seed plant Any plant that produces

seeds. Most seed plants belong to the phyla *Anthophyta (Ûowering plants) or *Coniferophyta (conifers).

Seger cones (pyrometric cones) A series of cones used to indicate the temperature inside a furnace or kiln. The cones are made from different mixtures of clay, limestone, feldspars, etc., and each one softens at a different temperature. The drooping of the vertex is an indication that the known softening temperature has been reached and thus the furnace temperature can be estimated.

segmentation 1. See metameric segmentation. 2. See cleavage.

segregation The separation of pairs of *alleles during the formation of reproductive cells so that they contain one allele only of each pair. Segregation is the result of the separation of *homologous chromosomes during *meiosis. See also mendel’s laws.

Segrè plot A plot of *neutron number (N) against *proton number (Z) for all stable nuclides. The stability of nuclei can be understood qualitatively on the basis of the nature of the strong interaction (see fundamental interactions) and the competition between this attractive force and the repulsive electrical force. The strong interaction is independent of electric charge, i.e. at any given separation the strong force between two neutrons is the same as that between two protons or between a proton or a neutron. Therefore, in the absence of the electrical repulsion between protons, the most stable nuclei would be those having equal numbers of neutrons and protons. The electrical repulsion shifts the balance to favour a greater number of neutrons, but a nucleus with too many neutrons is unstable, because not enough of them are paired with protons.

As the number of nucleons increases, the total energy of the electrical interaction increases faster than that of the nuclear interaction. The (positive, repulsive) electric potential energy of the nucleus increases approximately as Z2, while the (negative, attractive) nuclear potential energy increases approximately as N + Z with corrections for pairing effects. For large N + Z values, the electrical potential energy per nucleon grows much faster than the nuclear potential energy per nucleon, until a point is reached where the formation of a stable nucleus is impossible. The competition between the electric and nuclear forces therefore accounts for the increase with Z of the neutron–proton ratio in stable nuclei as well as the existence of maximum values for N + Z for stability. The plot is named after Emilio Segrè (1905–89). See binding energy; liq- uid-drop model; decay.

seif dune See dune.

735 |

selenium |

seismic waves A vibration propagated within the earth or along its surface as a result of an *earthquake or explosion.

Earthquakes generate two types of body waves that travel within the earth and two types of surface wave. The body waves consist of primary (or longitudinal) waves that impart a back-and-forth motion to rock particles along their path. They travel at speeds between 6 km per second in surface rock and 10.4 km per second near the earth’s core. Secondary (or transverse or shear) waves cause rock particles to move back and forth perpendicularly to their direction of propagation. They travel at between 3.4 km per second in surface rock and 7.2 km per second near the core.

The surface waves consist of Rayleigh waves (after Lord Rayleigh, who predicted them) and Love waves (after A. E. Love). The Love waves displace particles perpendicularly to the direction of propagation and have no longitudinal or vertical components. They travel in the surface layer above a solid layer of rock with different elastic characteristics. Rayleigh waves travel over the surface of an elastic solid giving an elliptical motion to rock particles. It is these Rayleigh waves that have the strongest effect on distant seismographs.

seismograph An instrument that records ground oscillations, e.g. those caused by earthquakes, volcanic activity, and explosions. Most modern seismographs are based on the inertia of a delicately suspended mass and depend on the measurement of the displacement between the mass and a point Üxed to the earth. Others measure the relative displacement between two points on earth. The record made by a seismograph is known as a seismogram.

seismology The branch of geology concerned with the study of earthquakes.

Selachii The major subclass of the Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous Üshes), containing the sharks, rays, skates, and similar but extinct forms. Their sharp teeth develop from the toothlike placoid *scales (denticles) and are rapidly replaced as they wear out.

selection (in biology) The process by

which one or more factors acting on a population produce differential mortality and favour the transmission of speciÜc characteristics to subsequent generations.

See artificial selection; natural selection; sexual selection.

selection pressure The extent to which organisms possessing a particular characteristic are either eliminated or favoured by environmental demands. It indicates the degree of intensity of *natural selection.

selection rules Rules that determine which transitions between different energy levels are possible in a system, such as an elementary particle, nucleus, atom, molecule, or crystal, described by quantum mechanics. Transitions cannot take place between any two energy levels. *Group theory, associated with the *symmetry of the system, determines which transitions, called allowed transitions, can take place and which transitions, called *forbidden transitions, cannot take place. Selection rules determined in this way are very useful in analysing the *spectra of quantum-mechanical systems.

selective breeding See breeding.

selectron See supersymmetry.

selenides Binary compounds of selenium with other more electropositive elements. Selenides of nonmetals are covalent (e.g. H2Se). Most metal selenides can be prepared by direct combination of the elements. Some are well-deÜned ionic compounds (containing Se2–), while others

are nonstoichiometric interstitial com- s pounds (e.g. Pd4Se, PdSe2).

selenium Symbol Se. A metalloid element belonging to group 16 (formerly VIB) of the periodic table; a.n. 34; r.a.m. 78.96; r.d. 4.81 (grey); m.p. 217°C (grey); b.p. 684.9°C. There are a number of allotropic forms, including grey, red, and black selenium. It occurs in sulphide ores of other metals and is obtained as a byproduct (e.g. from the anode sludge in electrolytic reÜning). The element is a semiconductor; the grey allotrope is lightsensitive and is used in photocells, xerography, and similar applications. Chemically, it resembles sulphur, and forms compounds with selenium in the