- •Introduction

- •1 Physical geography

- •5 The Sumerian language

- •6 History and chronology

- •15 Calendars and counting

- •17 Everyday life in Sumer

- •19 A note on Sumerian fashion

- •21 Death and burial

- •22 Sumerian mythology

- •23 Trade in the Sumerian World

- •26 Sumer, Akkad, Ebla and Anatolia

- •27 The Kingdom of Mari

- •29 Iran and its neighbors

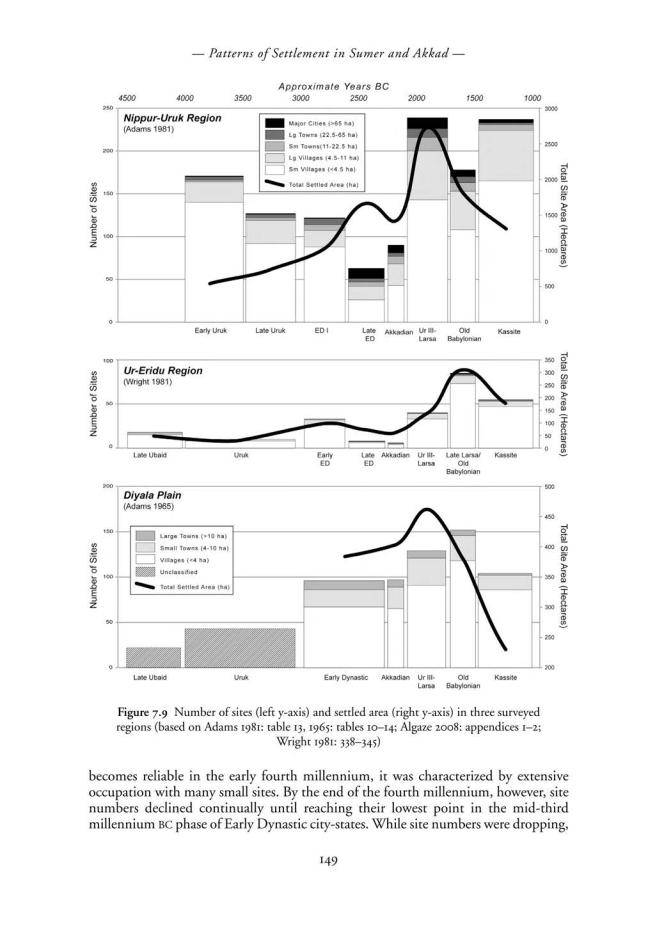

- •30 The Sumerians and the Gulf

- •32 Egypt and Mesopotamia

- •POSTSCRIPT

CHAPTER SIX

HISTORY AND CHRONOLOGY

Nicole Brisch

INTRODUCTION

The famous book title History Begins at Sumer that S. N. Kramer gave to a popular account of Mesopotamian ‘firsts’ in the history of humankind (first printing 1958) is in itself not without problems. Although the divide between history and prehistory is commonly marked by the invention of writing, the very earliest texts from Mesopotamia, when they can be read, offer only a small glimpse into archaic Mesopotamia, and moreover, only into the socio-economic history rather than chronology or a history of events. Additionally, the writing system of these earliest texts, which is referred to as either archaic or ‘proto-cuneiform,’ is still poorly under-

stood, in spite of giant steps towards its decipherment (Englund 1998).

The earliest history of Mesopotamia has often been associated with the Sumerians, who were credited with having invented writing and other markers of high civilisations, such as complex bureaucracies and trade systems (Algaze this volume). While there is an understandable wish to identify the actors who are behind the earliest history of ancient Mesopotamia, it should be emphasised at the beginning of this contribution, yet again, that the designation ‘Sumerian’ refers first and foremost to a language, not an ethnic group (see Michalowski 1999–2002, 2006: 159; Rubio 2005). The Sumerians referred to themselves as the ‘black-headed people’ (Sumerian: sag˜ g˜i6–ga) and called their homeland simply ‘native land’ (Sumerian: ki-en-gi, probably to be reconstructed as a word /kengi(r)/ = ki ‘place’ g˜ir ‘native’, see Steinkeller 1993: 112–113 n. 9). The Sumerian language was referred to as eme-g˜ir15, literally ‘native tongue/language’. In later sources, ki-en-gi is translated into Akkadian as ma¯t ˇumerims, the ‘Sumerian land’ or short ‘Sumer’, which encompasses the southern part of Mesopotamia (also referred to at a later date as Babylonia).

The origins of the Sumerians are shrouded in mystery. Beginning with the rediscovery of the ancient Near East in the West, scholars have debated whether the Sumerians were indigenous to southern Mesopotamia or not. This debate is often referred to as either the ‘Sumerian Problem’ or the ‘Sumerian Question’ (Potts 1997: 43–47 with previous literature; also see Postgate 1992: 23–24; Englund 1998: 73–81; Rubio 1999, 2005, 2007: 5–8; Crawford this volume) and has led some scholars, most notably Landsberger, to posit the existence of ‘Proto-Euphratean’ and ‘Proto-Tigridian’ substrate languages, which supposedly indicated an earlier, non-Sumerian speaking

111

–– Nicole Brisch ––

population that had been replaced by Sumerian speakers. Rubio (1999, 2005) has most convincingly discounted the arguments that have been brought forth in favour of reconstructing these ‘substrate’ languages. According to Rubio (1999), the words that were thought to have belonged to the substrate languages are either consistent with Sumerian or can be analysed as loanwords. The loanwords include words borrowed from a Semitic language, from Hurrian, or else they can be explained as ‘Arealwörter’, or ‘Wanderwörter’ (Rubio 1999, 2007: 7). Our difficulties in analysing word formation and morphographemic conventions are probably due to Sumerian being a linguistic isolate, that is, we cannot connect it with any other language or language family (see Cunningham this volume). However, one has to assume that there were several languages that must have belonged to the same family which did not survive because they were never written down (see Michalowski 2006: 162f.).

WRITTEN SOURCES

When discussing history and chronology, it is necessary to devote some space to the question of sources for the reconstruction of the most ancient history. For prehistoric or preliterate periods, archaeological indicators have to be used to distinguish time periods. These are stratigraphy and typology (Nissen 1988: 6). In ancient Mesopotamia, it is potsherds that offer the best chronological indicators for distinguishing time periods (Pollock 1999: 3). These methods of dating, while not without their problems, offer a relative chronology, by which is meant measuring time periods relative to each other to establish which is older and which is younger. Absolute chronology, that is, establishing the exact chronological distance to the present time, has to rely on other methods, such as radiocarbon dating (C14 method). However, in spite of great progress in calibrating radiocarbon dates, in particular of the earliest periods, they remain imprecise (Wright and Rupley 2001) and are difficult to connect to historical events (see already Crawford 1991: 18), and thus the chronology of the fourth and third millennia is rather insecure. Therefore, all the absolute dates mentioned in this chapter are rather tentative.

With the advent of writing–which was but one of several innovations that occurred around the same time–texts can be used to glean information on history. However, leaving issues of decipherment aside, as already mentioned above, the earliest texts offer little historical information if one is interested in a history of events. Textual genres that we encounter in early Mesopotamia are administrative texts, word or ‘lexical’ lists, literary texts, royal inscriptions and legal documents.

Administrative (or ‘archival’) texts are among the first texts that we encounter after the invention of writing. These texts recorded economic processes and are often associated with institutional administrations, thus offering important sources for the study of socio-economic histories. Beginning c.2500 BC, some administrative and legal texts are dated using the so-called year names. Kings began naming every year after a special event of the preceding year. Among the events are military conflicts (e.g. the conquest of cities), religious events (e.g. appointing high priestesses or fashioning of prestigious objects of worship), or building activities, such as the erecting of temples or city walls. In a few cases, ancient scribes compiled the individual year names into year lists, which can be used to reconstruct a particular king’s reign. However, it is not always clear whether the claims that were made in the year names can be taken at face value, because year names are also a convenient vehicle for royal propaganda.

112

–– History and chronology ––

Word lists (‘lexical lists’) were used to train scribes in writing (Civil 1995) and are also among the first text genres (Englund 1998: 82–110). Lexical texts enumerate and classify all ‘natural and cultural entities’ (Civil 1995: 2305). Among the earliest word lists are the list of professions, animals (pigs, fish, cattle) or other objects (wood, vessels, etc.). Some of the lists that are already known from proto-cuneiform texts, such as one of the lists of professions, were transmitted for more than a thousand years, even if they were not properly understood anymore.

The earliest literary texts did not appear until about six hundred years after writing was invented. Most of the very early literature is concerned with religion, praising deities and temples. However, the bulk of Sumerian literary texts date to the Old Babylonian period (c.1800 BC). Among the literary texts that have been popular sources for the reconstruction of history are the Royal Correspondence of Ur (Michalowski 2011b) and the Sumerian Kinglist (Jacobsen 1939; Steinkeller 2003). Although literary texts sometimes describe historical events, their use as primary sources for the reconstruction of history has been heavily critiqued (Liverani 1993b; Rubio 2007: 23–26; Michalowski 2011b).

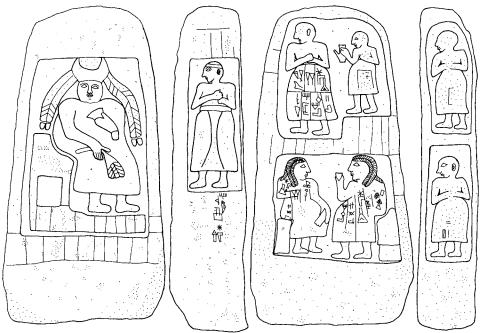

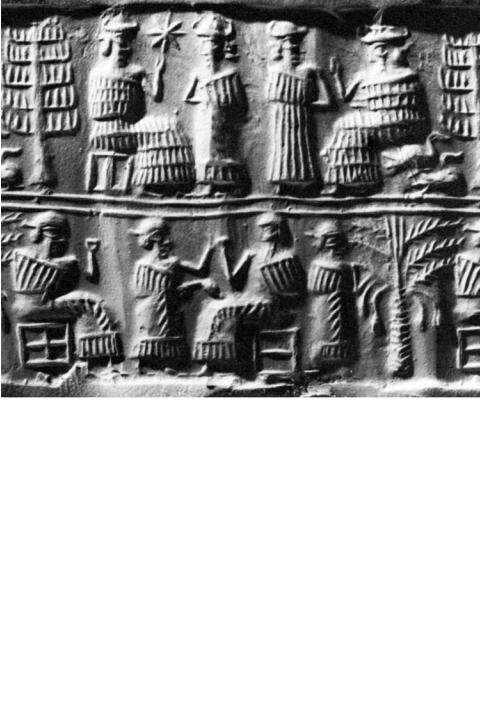

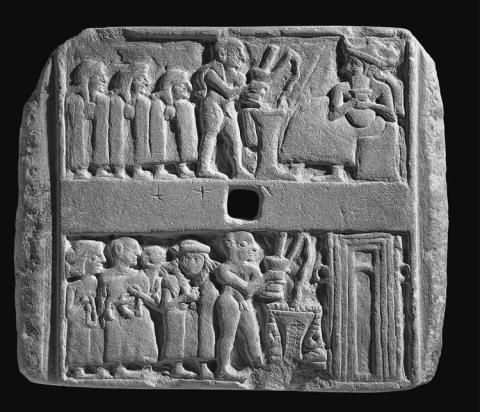

Royal inscriptions represent another important genre of the time periods described here. They are sometimes also called ‘monumental inscriptions’ (Hallo 1962) because they were inscribed upon objects (‘monuments’ in the widest sense). These inscriptions, which were written in the name of kings, or sometimes members of the royal family or other members of the elite, were either placed on architectural elements, such as bricks, clay nails, or clay cones, or on votive offerings for deities, such a stone vases, statues, or other precious objects. Some inscriptions were placed on stelae, possibly for public display (Cooper 1983a: 12), although it is unclear how many people would have been able to read the inscriptions. Some inscriptions only contain the name of a king, while other inscriptions, in particular of the later periods, can be long and include some narrations of events.

Legal texts, such as sale or loan documents, often show a list of witnesses to the transaction. They are also important sources for the study of socio-economic history. In addition, there are the so-called ‘law collections’ (Roth 1997), a mixture between royal inscriptions and legal pronouncements that modern scholars like to identify as ‘laws’.

None of the text genres mentioned here can be identified as historiographic literature in the strictest sense, although they may contain some, very limited information that will help in reconstructing history. Although a recent contribution on historiography seeks to redefine common conceptions of what historiography of early Mesopotamia is (Michalowski 2011a), it does not detract from the fact that most of the earliest texts were not only highly abbreviated, and thus rather enigmatic to the modern reader, but were also not composed to offer historically accurate information for future generations. Moreover, the textual evidence was part of the sphere of ancient elites. Thus, texts offer information on non-elite populations only as far as their spheres overlap. It is therefore important to recognize that our textual documentation for reconstructing this earliest history of ancient Mesopotamia is rather tenuous and biased.

An overview article such as the one presented here is necessarily abbreviated and many important contributions cannot be acknowledged. Writing on early Mesopotamian history poses a difficult task insofar as the sources are so varied and only attested for brief

113

–– Nicole Brisch ––

periods of time that are punctuated by long periods for which we have no written records. The information offered here is only designed as a starting point.

THE LATE URUK PERIOD: THE BEGINNINGS

The Uruk period, so named after the famous southern Mesopotamian city of Uruk, modern Warka, encompasses roughly the fourth millennium BC. The very end of the Uruk period sees the first emergence of state formation and the rise of urbanism and complex societies and the invention of writing. The Late Uruk period saw the birth of the city-state (Yoffee 2004), a form of political governance that remained important throughout the late fourth and third millennia.

The chronology of the fourth millennium, especially in southern Mesopotamia, is still rather vague, mainly due to lack of recent samples for radiocarbon dating (Wright and Rupley 2001) and most scholars avoid giving precise dates for the historical periods of the fourth and third millennia. Moreover, the chronology of northern Mesopotamia and other regions that were in contact with southern Mesopotamia, such as Anatolia, the Levant, and Southeast Iran, followed different prehistoric and chronological networks, which can only at times be linked to southern Mesopotamia.

As a result of a conference on the Uruk period (Rothman 2001), a new chronological framework for the Uruk period was developed. This framework sought to replace the common nomenclature of ‘Early’, ‘Middle’ and ‘Late Uruk period’ with the more neutral terms LC1–5, where LC stands for Late Chalcolithic (Rothman 2001: 7–8) (Table 6.1).

Radiocarbon dates from the city of Uruk itself, which would indicate that the Eanna precinct stratigraphic level IVa was built after 3500 BC, are problematic (Wright and Rupley 2001: 91–93), and radiocarbon samples from other areas indicate that the Late Uruk period (LC 5) came to end there before 3000 BC (northern Mesopotamia) and 3100 BC (south-western Iran) (Wright and Rupley 2001: 121). This has led some scholars to favour an end of the Late Uruk period (LC 5) at 3200/3150 BC (Nissen 2001: 152).

Although the city of Uruk itself was likely the most important and largest place of the Uruk period, it has been pointed out several times that there are problems regarding the stratigraphy and hence the dating of Uruk finds (Nissen 2001; 2004). In addition, excavations of Uruk period sites in southern Mesopotamia were rather restricted (Pollock 2001: 185), and thus our knowledge of the Uruk period in southern Mesopotamia is rather fragmentary.

As mentioned earlier, the Late Uruk period is important because it sees the emergence of states and the first cities (Algaze this volume; Nissen 1988; Pollock 1999). Among the innovations that can be observed are a great increase in settlements, leading to complex settlement patterns, a complex bureaucracy, the invention of writing, monumental art and architecture as well as other technological innovations. It is assumed that an increase in settlements, a trend that already began in the preceding Ubaid period, led to population growth and thus to a need for a higher degree of social organisation.

The earliest written records were found in rubbish layers that most likely date to the very end of the Late Uruk period (LC 5 = stratigraphic layer Eanna IVa) (Nissen 2001: 151). According to Nissen (2004: 6), ‘almost everything we ascribe to the (Late) Uruk period – whether architecture, or seals, or writing, or art – originates from the short

114

–– History and chronology ––

Table 6.1 |

Chronological framework for southern Mesopotamia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Date BC |

Southern Mesopotamia |

Uruk (Eanna) |

‘Late Chalcolithic’ |

|

|

|

|

3000 |

|

IVA |

|

|

Late Uruk |

Eanna |

LC 5 |

|

|

IVB–V |

|

|

|

|

Late |

|

|

Eanna |

|

|

|

VI |

|

3400 |

Late Middle Uruk |

Eanna |

LC 4 |

|

|

VII |

|

3600 |

Early Middle |

Eanna IX– |

LC 3 |

|

Uruk |

VIII |

|

3800 |

|

|

|

|

|

Eanna XI– |

Late |

|

|

X |

|

|

Early Uruk |

|

LC 2 |

4000 |

|

Eanna XII |

|

|

|

|

Early |

4200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

LC 1 |

|

Ubaid transitional |

Eanna |

|

|

Ubaid 4? |

XVI–XIV |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: after Rothman 2001: 7.

phase of Level IVa’, thus making our understanding of the processes of the Late Uruk period in the city of Uruk itself rather problematic.

The archaic or proto-cuneiform texts were divided into two groups, based on palaeographic distinction of the sign forms and comparisons to the slightly later site of Jamdat Nasr in southern Mesopotamia, Uruk IV and Uruk III, where Uruk III (c.3100–2900) is also referred to as Jamdat Nasr period.

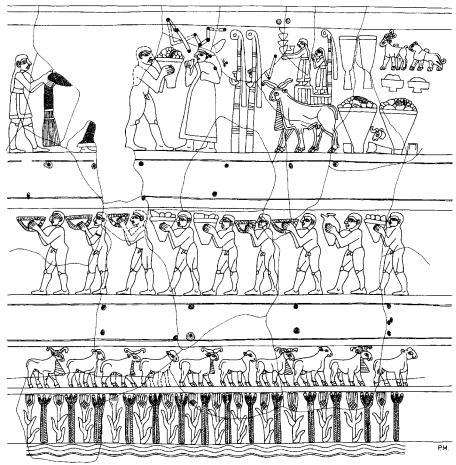

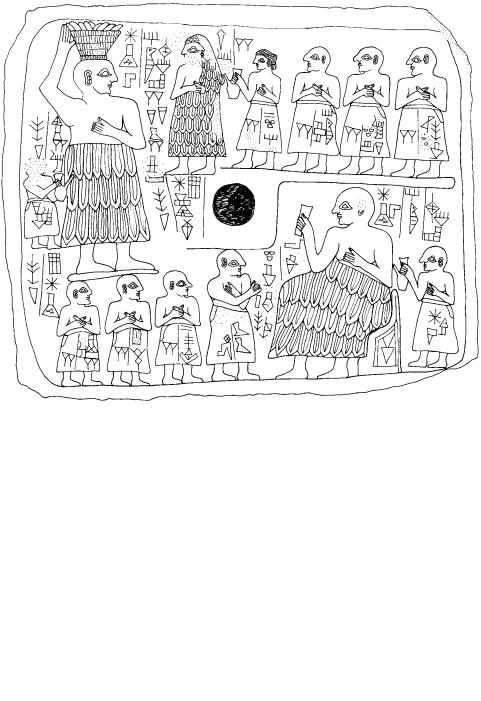

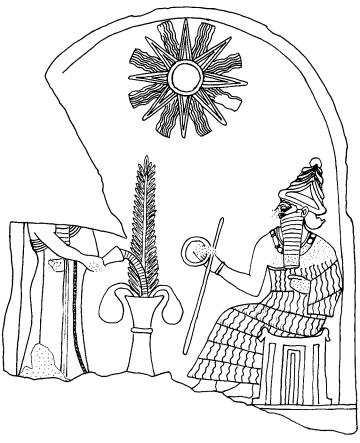

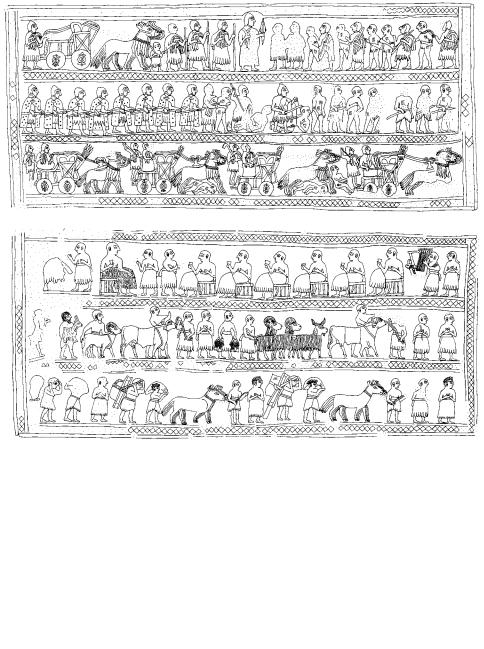

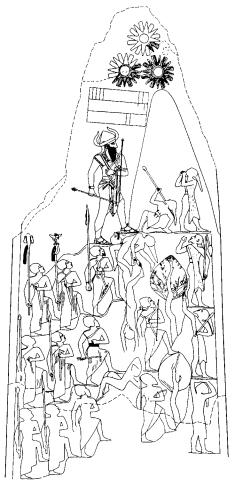

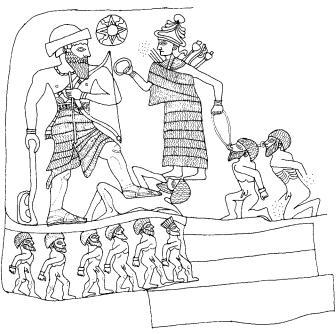

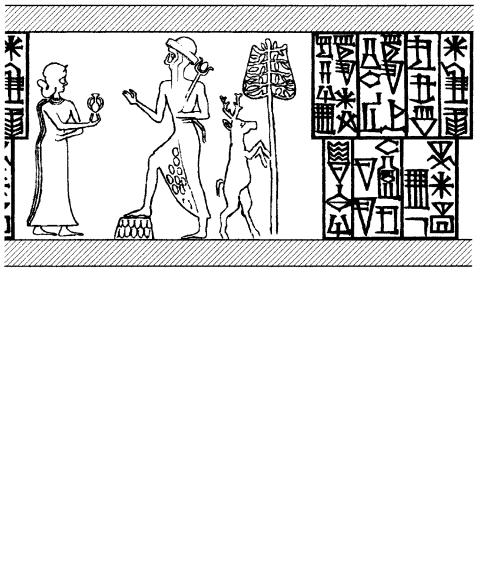

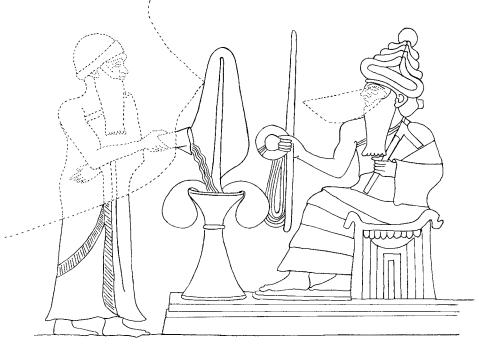

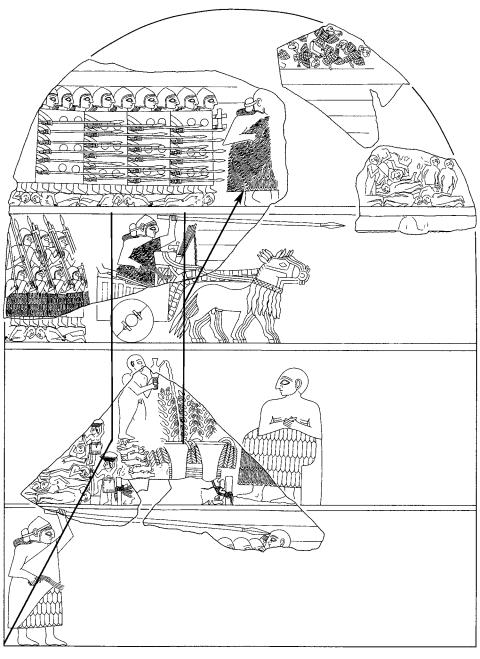

The ‘proto-cuneiform’ texts suggest that a complex and detailed administration of economic goods was maintained, dealing with, among other things, foods, such as fish, domesticated animals, grains, as well as labour, with some indications that slave labour may have been involved (Englund 1998: 176–183). Late Uruk society was probably organised hierarchically with a male figure as political leader. This is indicated by both visual representations of the so-called man in the net skirt, who is interpreted by some as depicting the concept of leadership rather than an individual leader (Pollock 1999: 184). In one monument, the man in the net skirt is depicted as hunting lions, a motif used to represent political leadership until the first millennium BC. Similarly, evidence from the word list of titles and professions (Englund 1998: 103–106 with further references) has led some scholars to argue that the list was sorted according to rank and

ˇ

that the first title, NAMESDA, describes the highest ranked individual, later equated with the Akkadian word ˇarrus ‘king’ (Nissen 2004: 13–14). Whether Late Uruk society was headed by a ‘priest-king’, whose claim to power was derived from religion, as some scholars have suggested (e.g. Van De Mieroop 2007: 27), is unclear (see the doubts raised by Nissen 2004: 14).

115

–– Nicole Brisch ––

THE EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD: WARRING CITY-STATES

Although not much is known about the Jamdat Nasr period, it is likely that southern Mesopotamia underwent profound changes during this period (Pollock 1999: 6). The Uruk ‘network’ of the Late Uruk period probably collapsed, as did some of the urban spaces (Pollock 1999: 6). In the following Early Dynastic (ED) period we gain a clearer picture of city-states and how they interacted with each other, especially for those periods when we have more and more written sources (Table 6.2).

Based on the stratigraphy from the excavations in the Diyala region of Iraq, the archaeologist Henri Frankfort divided the Early Dynastic period into three phases. ED III was then further subdivided into phases a and b (see below). There is a suggestion that the period ED II did not exist in southern Mesopotamia or outside of the Diyala region (Porada et al. 1992: 103). The term ‘Pre-Sargonic’, which is sometimes used to indicate the period immediately preceding the Old Akkadian period (ED IIIb), should probably be avoided, because it is relatively imprecise.

Levels of the Early Dynastic I–II period in southern Mesopotamia have been excavated in Nippur, Ur, Jamdat Nasr, Ubaid and Kish (Porada et al. 1992: 103–106). Radiocarbon dates from Nippur would support a date for the Early Dynastic I–II period in southern Mesopotamia of c.2900–2600 BC (Thomas 1992: 146). The most important archive of this period comes from the city of Ur (Burrows 1934) and can be dated into the late ED I period through stratigraphy (Porada et al. 1992: 105). Like the ‘proto-cuneiform’ texts, the archaic texts from Ur offer primarily information on the socio-economic history of this period. For example, the texts mention the title lugal, which later is translated as ‘king’, but it only occurs in personal names and there is no evidence that a lugal resided at Ur during this time (Wright 1969: 41). In addition, the texts mention both a temple(?) (AB) and a palace(?) (é-gal) (ibid.). And like the preceding periods, the textual evidence also indicates a specialisation of labour (Wright

1969: 122).

The above-mentioned Sumerian Kinglist (SKL), whose earliest manuscript dates to the Ur III period, is a list consisting of several dynasties that ruled over southern Mesopotamia. Many scholars have written and commented on the SKL, and not all their contributions can be acknowledged here. Several things are remarkable about the SKL: it lists individual dynasties according to the cities from which they ruled, listing

Table 6.2 Periods of third and early second millennium southern Mesopotamia

Dates BC |

Period |

|

|

c.3150/3100–2900 |

Jamdat Nasr Period (‘Uruk III’) |

c.2900–2600 |

Early Dynastic I–II |

c.2600–2500 |

Early Dynastic IIIa |

c.2500–2350 |

Early Dynastic IIIb |

c.2350–2200 |

Dynasty of Akkad/(Old) Akkadian |

c.2200–2112 |

Second Dynasty of Lagasˇ |

c.2112–2004 |

Third Dynasty of Ur/Ur III period |

c.2004–1595 |

Old Babylonian period |

|

(Early Old Babylonian c.2004–1763 [=Isin-Larsa period]; Old Babylonian |

|

c.1763–1595) |

|

|

116

–– History and chronology ––

every king individually including the number of years that they reigned. Especially the years for earlier kings are within the realm of fantasy: the first king of the city of Eridu is said to have reigned for 28,000 years! Moreover, at least the Old Babylonian version (c.1800 BC) begins with listing kings that ruled before the ‘Flood’, thus connecting mythical with historical times. All the dynasties that are mentioned in the SKL are listed as having reigned consecutively; even those dynasties that we now know were contemporaneous. Moreover, the dynasties of the city-state of Lagash were not mentioned at all, possibly indicating a rivalry between the authors of the SKL and the citystate of Lagash.

The early Mesopotamian concept of a royal dynasty was closely tied to the city that was its power base; this differs strongly from modern conceptions of royal dynasties, which are mainly defined through blood ties. Both royal inscriptions and the SKL only rarely give information on parentage of kings; instead, kings stated that their rule was legitimised through divine favour.

It has been suggested that the SKL created a fiction that southern Mesopotamia was always ruled by a single dynasty and therefore served as a tool of legitimisation for the Old Babylonian dynasty of Isin, who laid claim to a hegemonic rule over Mesopotamia (Michalowski 1983; Wilcke 1988). Although the new Ur III manuscript does not invalidate this claim, the differences between the two versions show that the Old Babylonian scribes took some liberties in transmitting the kinglist (Steinkeller 2003).

The passages of the SKL relating to what otherwise might be identified with the Early Dynastic I–II period seem particularly unreliable as historical sources: after the flood had swept over southern Mesopotamia, kingship first went to Kisˇ, then to Uruk, listing legendary kings of Uruk, such as Lugalbanda, Dumuzi and Gilgamesh. Because we are lacking information from other sources, such as royal inscriptions, that these kings ever existed (although they are mentioned in Sumerian myths, see Vanstiphout 2003), they have to be considered mythical. Moreover, as Steinkeller (2003: 285–286) has suggested, it is likely that the mythical kings of Uruk and other dynasties were only inserted into the SKL in the Old Babylonian period, in order to break up the long dynasty of Kish and show a higher turn-over rate between dynasties and cities, which then offered greater legitimacy to the kings of Isin, who saw themselves as the heirs to the Ur III state.

With the Early Dynastic III period, the fog of prehistory slowly begins to lift. The subdivision of the ED III period into a and b was made on the basis of texts, archaeologically there is no break between the two sub-phases (Porada et al. 1992: 111–112). However, the different terminology for ED IIIa and b is still unclear and ill defined (Porada et al. 1992: 108–109).

The two most important archives of ED III come from the cities of Fara (ancient Shurrupak) and Tell Abu Salabikh (possibly ancient Eresh). They are roughly contemporary and commonly dated to the ED IIIa period. Shurrupak is mentioned in the Old Babylonian version of the SKL as the last dynasty before the flood (Krebernik 1998: 241), yet no year dates or royal names appear in the archives. The language of the Fara and Abu Salabikh texts is overwhelmingly Sumerian, as are the personal names mentioned in these archives, but the first Semitic texts and personal names appear (Krebernik 1998: 260–270). Based on palaeography, it has been suggested that the archives are contemporary to king Mesalim (or Mesilim) of Kish (Krebernik 1998: 158f.). We know from royal inscriptions that Mesalim predates the kings mentioned in Table 6.3, but at this stage he cannot be placed within a relative or absolute chronology.

117

–– Nicole Brisch ––

Table 6.3 |

Some kings of Early Dynastic III |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||

Dates/ |

Ur I |

Lagash I |

Proposed |

ED IIIa/IIIb? |

||

Period |

|

|

|

|

Synchronisms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ED IIIa |

• |

Meskalamdug |

• |

Ur-Nansˇe |

Ur-Nansˇe and |

ED IIIb begins |

(c.2600– |

|

‘king of Kisˇ’ |

|

|

Akurgal = |

either with |

2500 BC) |

|

|

|

|

Meskalamdug |

Ur-Nansˇe of Lagasˇ |

|

|

|

|

|

and Akalamdug |

|

ED IIIb |

• |

Akalamdug |

• |

Akurgal |

Mesanepada of |

or with |

(c.2500– |

|

‘king of Ur’ |

|

|

Ur = Eannatum |

Mesanepada of |

2350 BC) |

|

(Meskalamdug’s |

|

|

of Lagasˇ |

Ur and Eannatum |

|

|

son?) |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Mesanepada |

• |

Eannatum |

|

|

|

|

‘king of Ur’, son |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of Meskalamdug |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Meskiagnun |

• |

Enannatum I |

|

|

|

|

‘king of Ur’ |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Elili ‘king of Ur’ |

• |

Enmetena |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Enannatum II |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Enentarzid |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

Lugalanda |

|

|

|

|

|

• |

UruKAgina/ IriKAgina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Only the first dynasties of Ur and Lagash and the kings that are attested in royal inscriptions are considered here. Royal names in bold script are kings mentioned in the Sumerian Kinglist.

While the administrative texts from Fara had for a long time been thought of as documents of a private administration, new research has shown that they were part of a centralised administration with a ruler at the helm (Krebernik 1998: 312 with further literature).

When the texts from Tell Abu Salabikh were published for the first time (Biggs 1974), they created a sensation, because some of the tablets were shown to be the first literary texts. Among them are the Kesh Temple Hymn and the ‘Instructions of Shurrupak’, both of which were transmitted into the Old Babylonian period, some seven hundred years later (Krebernik 1998: 317). Unfortunately, much of this earliest literature is difficult to understand because of the highly abbreviated nature of the early writing system and because of some early experiments with different orthographies (‘UD.GAL.NUN’).

There is some disagreement on where to put the dividing line between ED IIIa and IIIb. Porada et al. (1992: 108) place Ur-Nanshe of Lagash and his dynasty within the ED IIIa period and contemporary to the Fara and Tell Abu Salabikh tablets, whereas Biggs (1974: 26) and Bauer (1998: 432) assume that there are one to two generations between the Fara and Tell Abu Salabikh archives and the first ruler of Lagash, Ur-Nanshe (see Table 6.3). However, as Biggs (1974) already pointed out, palaeography is not a very reliable chronological indicator.

The earliest ruler from the SKL, whose existence can be verified through contemporary sources, namely royal inscriptions (Frayne 2008: 55–57), is Enmebaragesi

118

–– History and chronology ––

(Mebaragesi), whom the SKL identifies as the penultimate king of the first dynasty of Kish. In the SKL of the Old Babylonian period, the first dynasty of Kish is listed as the first dynasty after the ‘Flood’, whereas the Ur III version does not mention any floods and instead begins with the first dynasty of Kish. However, it is virtually impossible to place this king within the Early Dynastic period.

Some rulers of the Early Dynastic period claim a title lugal kisˇ ‘king of Kish’ even though their geographical affiliation is unknown otherwise (Frayne 2008: 67). It has been frequently suggested that this indicated that the city of Kish exercised some kind of hegemony over large parts of southern Mesopotamia. However, there no substantial evidence for this and it is possible that the title was just an honorific (ibid.: 67; Rubio

2007: 15–6 and n. 10).

The famous Royal Cemetery of Ur, which has yielded some of the most important archaeological finds of the Early Dynastic period (Vogel this volume), is also dated into ED IIIa, because the seals of Meskalamdug and Akalamdug were considered to be stylistically earlier than those of Mesanepada and his wife (Porada et al. 1992: 111). However, if one considers the ED IIIb period to have begun with Ur-Nanshe and Meskalamdug (see Table 6.3), it would lead to a dating of the Royal Cemetery of Ur to ED IIIb. For calibrated radiocarbon dates from the Royal Cemetery see Thomas (1992: 147), who points out general problems with dating the ‘Old Kingdom and Early Dynastic III horizon’.

The Early Dynastic IIIb period offers marginally more historical clarity. Most of the sources for ED IIIb come from the city-state of Lagash, whose capital was at first the city of Lagash (modern name: al-Hiba) and then moved to the city of Girsu (modern name: Tello). For the first time there is more extensive evidence in the texts that point to political and military conflicts, indicating a wish to expand the political territory of individual city-states and numerous conflicts between the city-states. The best known of such conflicts, which may have begun in the ED IIIa period already, was the border conflict between the city-states of Umma and Lagash, for which Mesalim had to be called in as a mediator (Cooper 1983a). Because our main sources for the conflict come from Lagash and are therefore biased in favour of Lagash’s rightful claims, it is difficult to find reliable information on the causes of the conflict. Yet the very fact of its existence and the fact that the conflict was recorded in writing show that a new era is slowly emerging.

Our main written source for the socio-economic history of this period is an important archive of ca. 1700 tablets from Lagash, which details the administrative procedures in the queen’s household (é-munus). The study of this archive had in the 1920s led to the assumption that temples dominated the economy. More recent studies show that the picture is much more complex and that the idea of the ‘Sumerian temple economy’ can no longer be upheld (Beld 2002).

In addition to military conflicts, the royal inscriptions of the ED III period often mention the building of temples in various cities. The first king in Mesopotamian history to institute reforms and release his citizens from work obligation, including debt, was Emetena (Entemena) (Bauer 1998: 471). This already points to internal economic and social problems that kings needed to address by occasionally instituting reforms, a phenomenon that is well known from later periods of Mesopotamian history. The best-known reform text is known from UruKAgina (IriKAgina), the last independent ruler of Lagash (Beld 2002: 79–84). Scholars have offered different opinions on this text. It appears clear that the UruKAgina sought to regulate central

119

–– Nicole Brisch ––

administration and some property that previously belonged to the ruler was now

officially held by gods (Ningirsu, Baba and ˇulsˇagana). However, it is likely that these

S

reforms, which had the goal of limiting the power of high-standing administrators, were actually designed to strengthen the ruler’s power (Beld 2002: 81).

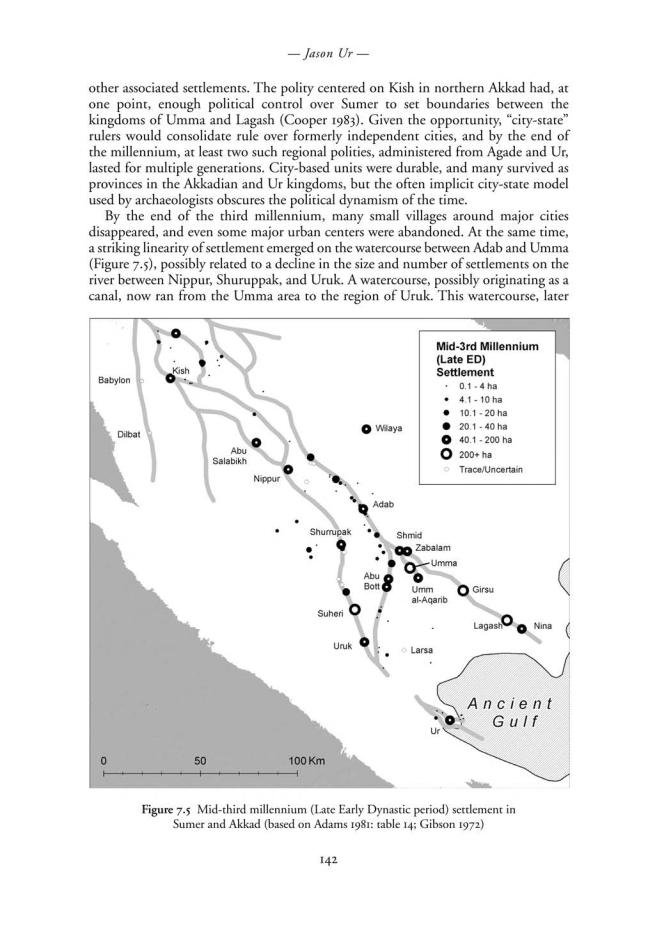

The frequent mention of military conflicts in the royal inscriptions of the ED IIIb period suggest that there were power struggles among the city-states. There are indications that several rulers attempted to expand their area of influence. This attempt seems to have culminated in the efforts of Lugalzagesi, a king of Umma. The SKL mentions him as the only ruler of a dynasty of Uruk that immediately preceded the dynasty of Akkad (see below). Lugalzagesi finally succeeds in conquering the city-state of Lagasˇ and deposes of its last independent ruler, UruKAgina. He claimed to have expanded his area of influence to the entire area of Sumer, that is, southern Mesopotamia, as well as foreign countries (Bauer 1998: 494).

THE FIRST EMPIRE? THE STATE OF AKKAD

The (Old) Akkadian period (c.2330–2200 BC), also called the Sargonic period, immediately follows the ED III period, and although historical information is slightly better than before, there still remain many uncertainties relating to history and chronology (Table 6.4). To cite A. Westenholz (1999: 18): ‘Almost everything pertaining to the Sargonic period is a matter of controversy.’

The state of Akkad has been celebrated as the ‘First World Empire’ (Liverani 1993a), although there is a still ongoing debate of how to define ancient empires. Notwithstanding, there is no doubt that the state of Akkad created a new paradigm of kingship and statehood in early Mesopotamia – that of the territorial state seeking to expand its boundaries and seeking to institute a centralised rule.

From about the middle of the third millennium until the end of the Old Babylonian period, one can observe that political governance went back and forth between these two forms of governing – the localised, relatively small city-state and the centralised, territorial state. While territorial states never lasted very long, the history of early Mesopotamia is full of instances in which hegemony was tried and achieved, yet only for brief periods of time.

Table 6.4 Kings of the Dynasty of Akkad

Sargon |

2334–2279 |

Rı¯musˇ |

2278–2270 |

Manisˇtusˇu |

2269–225 |

Nara¯m-Sîn |

2254–2218 |

ˇ |

2217–2193 |

Sar-kali-ˇarrı¯s |

|

Igigi |

|

Naniyum |

2192–2190 |

Imi |

|

Elulu |

|

Dudu |

2189–2169 |

ˇ |

2168–2154 |

Su-Turul |

Source: after Brinkman 1977.

120

–– History and chronology ––

It is possible that Lugalzagesi and Sargon, the first ruler of the dynasty of Akkad, overlapped for some time (McMahon 2006: 4). A. Westenholz (1999: 35) suggests that they overlapped for ten years before Sargon defeated Lugalzagesi while admitting that this number is ‘guesswork’, also because it is still unclear how long Sargon’s reign lasted. Although Sargon succeeded in defeating Lugalzagesi and although he is considered to be the founder of the Old Akkadian dynasty, it appears that he governed by leaving most of the administrative structures of the southern Babylonian city-states intact (A. Westenholz 1999: 50), leading to Liverani’s (1993a: 4) pointed assessment that Sargon himself is really ‘pre-Sargonic’. This serves to show that the boundaries between historical periods, in particular during the third millennium, are rather fluid, something that is also supported by the archaeological evidence from the city of Nippur (McMahon 2006), where no stratigraphic breaks can be observed in the transition from Early Dynastic to Akkad and material culture shows some continuity.

Historical information about the two most important kings of the dynasty of Akkad, Sargon and Nara¯m-Sîn, is difficult to disentangle, because both were immortalised in literary stories surrounding their lives and rule (J.G. Westenholz 1997). According to legend, Sargon began his career as a high-standing official (‘cup-bearer’) of king Urzababa in the city of Kish (A. Westenholz 1999: 35). There is a possibility that Sargon created for the first time in history a standing army, although this is also a matter of contention.

Through military campaigns Sargon was able to expand his area of influence, which certainly included all of southern Mesopotamia, yet it is not clear how far to the north and east his influence extended. The new capital of Sargon’s state was moved to the city of Akkad, which, it is assumed, lay somewhere in northern Babylonia, though no definite location has been identified as yet (A. Westenholz 1999: 31–34). Inscriptions seem to indicate that Sargon destroyed some of the cities of the south and replaced the previous rulers with local governors loyal to him (Postgate 1992: 40).

The new conquest of southern Babylonia led to several revolts of the southern citystates, which are reported under Rı¯mush and Nara¯m-Sîn. It is possible that the revolts were due to large-scale expropriations of land (Postgate 1992: 41). However, the most famous monument recording the (forced?) sale of land is the well-known Manisˇtusˇu obelisk (Gelb et al. 1991: 2 et passim), which records land sales of northern Babylonia (A. Westenholz 1999: 44). Since the revolt came mostly from the southern city-states, it is unclear whether land sales were a direct cause for rebellion and it is more likely that the revolts had multiple reasons, of which land expropriation was only one (A. Westenholz 1999: 46).

The more profound changes in the administration and territorial expansion seem to have come under Nara¯m-Sîn, who was Sargon’s grandson according to the SKL. Sargon and Nara¯m-Sîn led several campaigns that took them as far as areas that are today in northern Syria, Turkey and western Iran, going, in their own words, where no king had gone before. As Nara¯m-Sîn seems to have repeated some of the campaigns that already took place under Sargon, it is unlikely that they were more than raids (Van De Mieroop 2007: 67). Nara¯m-Sîn is also well known because of a great rebellion of southern Babylonia that occurred during his reign. Reliable information on the exact nature and circumstances of this rebellion is hard to come by, because we know of the rebellion mainly from Nara¯m-Sîn’s own inscriptions. As it is unclear whether Nara¯m-Sîn reigned for thirty-seven or fifty-four years (A. Westenholz 1999: 47), it is difficult to place the

121

–– Nicole Brisch ––

rebellion within his reign, although A. Westenholz (2000: 553) now seems to place it rather towards the end of Nara¯m-Sîn’s reign. Nara¯m-Sîn reports the successful defeat of the rebellion and declared that in response to his success the people of the city of Akkad asked him to be their god, making him the first deified king in Mesopotamian history.

Nara¯m-Sîn became immortalised as an Unglücksherrscher in the Sumerian tale of the Curse of Akkad (Cooper 1983b, 1993). The tale does not connect his misfortunes with his deification but rather states that the king failed to obtain the proper omen to build the god Enlil’s temple in Nippur. Enlil was already at that time the highest god in the Mesopotamian pantheon and Nippur was the religious centre, therefore, the failure to obtain the proper omen to build the temple can be seen as a serious failing on the king’s part and shows at the same time that the most important god had withdrawn his divine favour, thus depriving Nara¯m-Sîn of his legitimate right to reign and leading to Akkad’s downfall. As a literary tale it tells us about what Mesopotamians thought was the cause of Akkad’s collapse.

Administrative sources indicate that the state of Akkad began to collapse under

Nara¯m-Sîn’s successor ˇar-kali-ˇarrı¯,s probably due to a combination of internal and

S

external problems.

During the Old Akkadian period the first administrative documents written in Akkadian, the oldest Semitic language, appear, and royal inscriptions were also frequently written in Akkadian. In particular the history of the dynasty of Akkad has sometimes led modern scholars to see an ethnic (Sumerian–Akkadian) or geographic (southern–northern) dichotomy that clashed at various times in history. However, the construction of such dichotomies may be rather due more to the wish of modern scholars to explain complex historical processes than actual dichotomies (Rubio 2007).

The Second Dynasty of Lagash and the Third Dynasty of Ur: a Sumerian renaissance?

After the fall of Akkad, it appears that a group of non-indigenous peoples called Gutium took advantage of the power vacuum. This phase is sometimes referred to as the Post-Akkadian period (Porada et al. 1992: 116–117). Different dates are given for the end of the dynasty of Akkad. Porada et al. (1992: 116) put the end of the dynasty of Akkad at 2150, whereas some radiocarbon dates seem to indicate an end of Akkad at 2250 (Thomas 1992: 148). It is unclear how long this ‘intermediate’ period lasted, and because of the (almost complete) absence of written records it is difficult to reconstruct events between the Akkad dynasty and the Third Dynasty of Ur (also called Ur III, 2112–2004). Sources from around the beginning of the Ur III period frequently mention expelling the Gutium from Babylonia, first under Utuhegal, a king of Uruk, who overlapped with Ur-Namma of Ur, then under Ur-Namma himself.

The chronology of the Second Dynasty of Lagash remains difficult, not even the sequence of rulers is certain (Table 6.5). However, a synchronism between Gudea of Lagash, the best-known ruler of Lagasˇ, and Ur-Namma of Ur now seems fairly accepted (Steinkeller 1988; Suter 2000: 15–17, with further literature). Gudea is well known because a number of inscribed statues were excavated at Girsu and because two cylinders recorded how Gudea built the god Ningirsu’s temple at Girsu. The cylinders (Edzard 1997: 68–106), which probably were originally placed in a temple (Suter 2000:

122

–– History and chronology ––

Table 6.5 Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III)

Ur-Namma |

2112–2094 |

ˇ |

2095–2046 |

Sulgi |

|

Amar-Suen |

2045–2037 |

ˇ |

2036–2028 |

Su¯ -Sîn |

|

Ibbi-Sîn |

2027–2004 |

|

|

Source: after Brinkman 1977.

71), are the longest literary compositions written in Sumerian from the third millennium.

It is possible that Ur-Namma, the founder of the Ur III dynasty, was a brother (or son) of Utuhegal, a king of Uruk (Sallaberger 1999: 132 with older literature). Ur-Namma began as a general under Utuhegal and then seems to have become independent and founded his new state. Not much is known about the earliest phases of the state due to a lack of written sources.

The Ur III period has left an unprecedented quantity of administrative texts, written in Sumerian, indicating a very tight and possibly restrictive administration. The latest figures estimate a grand total of about 120,000 administrative texts from this period alone, of which about 75,000 have been published (Molina 2008). By contrast, there are very few literary and lexical texts and relatively few sale documents.

Ur-Namma is known for having built an extensive canal system throughout southern Mesopotamia, introducing some administrative reforms (Sallaberger 1999: 134–137), and building several temple towers (‘ziqqurats’) in major centres of the south: Ur, Uruk, Nippur and Eridu (Porada et al. 1992: 117). The first law code, a collection of legal statements written in the name of the king, can also be attributed to this king (Roth 1997: 13–22). There is a suggestion that Ur-Namma died on the battlefield, although this is only indicated from the Sumerian literary composition The Death of Ur-Namma (Flückiger-Hawker 1999: 93–182). Michalowski (2008) has argued that this must have put the relatively new state of Ur into disarray.

Ur-Namma’s son and successor ˇulgi built upon his father’s achievements and

S

introduced more administrative reforms that were designed to streamline and centralise

the Ur III administration (Steinkeller 1991; Sallaberger 1999: 140–163). ˇulgi reigned for

S

a total of forty-eight years, an exceedingly long time to reign for a Mesopotamian

monarch. ˇulgi was also deified, just like his predecessor Nara¯m-Sîn. This time we have

S

much more information on temples that were built for the worship of the living king as well as statues of deified kings and priests and priestesses that attended to their cult.

ˇ ˇ

Sulgi was succeeded by Amar-Suen and Su¯ -Sîn, both of whom reigned for a relatively short period of time (nine and seven years). Amar-Suen later on acquired a reputation as an unlucky ruler, as evidenced in a Sumerian literary text that was written about him.

During its apex, the state of Ur III reached as far as south-west Iran and into northern Mesopotamia, although it is likely that some provinces remained under relatively loose control.

Like all territorial states of the third millennium, the Ur III state was relatively fragile

and centred on charismatic rulers, such as Sargon, Nara¯m-Sîn, Ur-Namma and ˇulgi.

S

123

–– Nicole Brisch ––

It is with the last ruler of Ur III, Ibbi-Sîn, that the state began to collapse. A food shortage combined with sky-rocketing food prices during the reign of Ibbi-Sîn indicate the beginning collapse of the centralised administration (Sallaberger 1999: 174–178). Unfortunately, much of our information regarding the collapse of the Ur III state comes from the Royal Correspondence of Ur (Michalowski 2011b), a literary correspondence that is only known from Old Babylonian copies. Whether the correspondence is historically accurate cannot be established at this point.

It appears that one of Ibbi-Sîn’s generals, Isˇbi-Erra, decided to defect from Ibbi-Sîn and established a new dynasty in the northern Babylonian city of Isin. The dynasties of Isin and Larsa belong to a new era, the Old Babylonian period (c.2003–1595 BC). Some scholars refer to this period as the ‘Amorite age’ (Charpin 2004), because many of the Old Babylonian kings were presumably of Amorite origin; the overwhelming majority of Old Babylonian literature and royal inscriptions as well as year names continued to be written in Sumerian. Scholars are still debating whether Sumerian had died out as a spoken language in the Old Babylonian period. In fact, the majority of Sumerian literature is known from tablets dating to the Old Babylonian period. Nevertheless, Sumerian began a new life as a sacred language and continued to be used for sacred texts until the end of the cuneiform tradition.

CONCLUSION

Writing about history and chronology of the late fourth and third millennia in Mesopotamia shows that one cannot write one history but several histories that together form a patchwork of information with varying degrees of certainty. Because of these uncertainties, most scholars write cultural histories of early Mesopotamia that focus on socio-economic, religious, or other aspects of early Mesopotamian history. Here I have attempted to write a more linear history, whether successful or not is unclear. A few general tendencies may be observed: because of the lack of reliable information, historians frequently have to fill the gaps with suggestions, and often it is not easy to separate fact from ‘fiction’. While this contribution has focused on written sources, the archaeology may offer a different picture, and it is not always clear what impact changes in political governance had on people that were not members of the elites. But this has to remain subject to another study.

FURTHER READING

General introductions into the early history and culture of Mesopotamia can be found in Bauer et al. 1998; Crawford 1991; Nissen 1988; Pollock 1999; Postgate 1992; Sallaberger and A. Westenholz 1999; Van De Mieroop 2007; Yoffee 2004.

REFERENCES

Bauer, J. 1998. “Der Vorsargonische Abschnitt der Mesopotamischen Geschichte.” In Bauer et al., pp. 429–585.

Bauer, J., Englund, R.K., Krebernik, M. 1998. Mesopotamien. Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. Annäherungen, 1. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 160/1. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag.

Beld, S.G. 2002. “The Queen of Lagash: Ritual Economy in a Sumerian State.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: UMI.

124

–– History and chronology ––

Biggs, R.D. 1974. Inscriptions from Tell Abu¯ Sala¯bih. Oriental Institute Publications, 99. Chicago: The |

||

Oriental Institute. |

. |

˘ |

|

||

|

|

|

Brinkman, J.A. 1977. “Mesopotamian Chronology of the Historical Period.” Appendix in Ancient |

||

Mesopotamia. Portrait of a Dead Civilization, ed. A.L. Oppenheim, pp. 335–348. Revised edition completed by E. Reiner. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Burrows, E. 1934. Archaic Texts. Ur Excavations Texts, 2. London: Harrison and Sons, Ltd. Charpin, D. 2004. “Histoire Politique du Proche-Orient Amorite (2002–1595)”. In Mesopotamien:

die altbabylonische Zeit, eds. D. Charpin, D.O. Edzard, M. Stol, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 160/4, pp. 23–482. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag.

Civil, M. 1995. Ancient Mesopotamian Lexicography. In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, ed. J. Sasson, vol. IV, pp. 2305–2314. New York: Scribner.

Cooper, J.S. 1983a. Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions: the Lagash-Umma border conflict. Sources from the Ancient Near East, 2/1. Malibu: Undena.

——1983b. The Curse of Agade. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

——1993. “Paradigm and Propaganda. The Dynasty of Akkade in the 21st century.” In Liverani

1993a, pp. 11–23.

Crawford, H. 1991. Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edzard, D.O. 1997. Gudea and His Dynasty. Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Periods, 3/1. Toronto: The University of Toronto Press.

Englund, R.K. 1998. “Texts from the Late Uruk Period.” In Bauer et al., pp. 13–233. Flückiger-Hawker, E. 1999. Ur-Namma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition. Orbis Biblicus et

Orientalis, 166. Fribourg, Switzerland: University Press.

Frayne, D.R. 2008. Presargonic Period (2700–2350 BC). The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Periods, vol. I. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Gelb, I.J., Steinkeller, P. and Whiting, R.M. 1991. Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus. Oriental Institute Publications, 104. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

Hallo, W.W. 1962. “The Royal Inscriptions of Ur: A Typology.” Hebrew Union College Annual 33: 1–43. Jacobsen, T. 1939. The Sumerian Kinglist. Assyriological Studies, 11. Chicago: The Oriental Institute. Krebernik, M. 1998. “Die Texte aus Fa¯ra und Tell Abu¯ Sala¯bı¯h.” In Bauer et al., pp. 235–427.

Kramer, S.N. 1958. History Begins at Sumer. London: Thames˘and Hudson.

Liverani, M. 1993a. Akkad. The First World Empire. Structure, Ideology, Traditions. History of the Ancient Near East/Studies, vol. 5. Padova: Sargon srl.

—— 1993b. “Model and Actualization.” In Liverani 1993a, pp. 41–67.

McMahon, A. 2006. The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition. Oriental Institute Publications, 129. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

Michalowski, P. 1983. “History as a Charter. Some Observations on the Sumerian Kinglist.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 103: 237–248.

——1999–2002. “Histoire (de Sumer).” In Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible, eds. J. Briend and M. Quesnel, pp. 108–124. Paris: Letouzy & Ané.

——2006. “The Lives of the Sumerian Language.” In Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures, ed. S. Sanders, Oriental Institute Seminars, 2, pp. 159–184. Chicago: The Oriental Institute Press.

——2008. “The Mortal Kings of Ur. A Short Century of Divine Rule in Mesopotamia.” In Religion and Power. Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond, ed. N. Brisch, Oriental Institute Seminars, 4, pp. 33–45. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

——2011a. “Early Mesopotamia.” In The Oxford History of Historical Writing, eds. A. Feldherr and G. Hardy, pp. 5–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——2011b. Correspondence of the Kings of Ur. An Epistolary History of an Ancient Mesopotamian Kingdom. Mesopotamian Civilizations, 15. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

Molina, M. 2008. “The Corpus of Neo-Sumerian Tablets: an overview.” In The Growth of an Early State in Mesopotamia: Studies in Ur III Administration, eds. S.J. Garfinkle and J.C. Johnson, pp. 19–61. Biblioteca del Próxomo Oriente Antiguo, 5. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

125

–– Nicole Brisch ––

Nissen, H. 1988. The Early History of the Ancient Near East. 9000–2000 B.C. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

——2001. “Cultural and Political Networks in the Ancient Near East during the Fourth and Third Millennia B.C.” In Uruk Mesopotamia & Its Neighbors. Cross-Cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation, ed. M. Rothman, pp. 149–179. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

——2004. “Uruk: Key Site of the Period and Key Site of the Problem.” In Artefacts of Complexity: Tracking the Uruk in the Near East, ed. J.N. Postgate. Iraq Archaeological Reports, 5, pp. 1–16. Cambridge: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (2002; reprinted 2004).

Pollock, S. 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia. The Eden that Never Was. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— 2001. “The Uruk Period in Southern Mesopotamia.” In Rothman, 2001 pp. 191–232. Porada, E., Hansen, D.P., Dunham, S. and Babcock, S. 1992. “The Chronology of Mesopotamia, ca.

7000–1600 B.C.” In Chronologies in Old World Archaeology, ed. R.W. Ehrich (3rd edition), pp. 77–121. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Postgate, J.N. 1992. Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history. London: Routledge.

Potts, D.T. 1997. Mesopotamian Civilization. The Material Foundations. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Roth, M.T. 1997. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (2nd edition). SBL Writings from the Ancient World, 6. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

Rothman, M.S. (ed.) 2001. Uruk Mesopotamia & Its Neighbors. Cross-Cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Rubio, G. 1999. “On the Alleged ‘Pre-Sumerian Substratum’.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 51: 1–16.

——2005. “On the Linguistic Landscape of Early Mesopotamia.” In Ethnicity in Ancient Mesopotamia. Papers Read at the 48th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden 1–5 July 2002, ed. W.H. Van Soldt, pp. 316–332. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten.

——2007. “From Sumer to Babylon: Topics in the History of Southern Mesopotamia.” In Current Issues in the History of the Ancient Near East, ed. M.W. Chavalas. Publications of the Association of Ancient Historians, 8, pp. 5–51. Claremont: Regina Books.

Sallaberger, W. 1999. “Ur III-Zeit.” In Sallaberger and Westenholz, pp. 119–390.

Sallaberger, W. and Westenholz, A. 1999. Mesopotamien. Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 160/3. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universitätsverlag.

Steinkeller, P. 1988. “The Date of Gudea and his Dynasty.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 40: 47–53.

——1991. “The Administration and Economic Organization of the Ur III State: The Core and the Periphery.” In The Organization of Power: Aspects of Bureaucracy in the Ancient Near East, eds. M. Gibson and R.D. Biggs, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations, 46, pp. 15–33. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

——1993. “Early Political Development in Mesopotamia and the Origins of the Sargonic Empire.” In Liverani, pp.107–129.

——2003. “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List.” In Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift für Claus Wilcke, ed. W. Sallaberger, K. Volk, and A. Zgoll, pp. 267–292. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Suter, C. 2000. Gudea’s Temple Building. The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image. Cuneiform Monographs, 17. Groningen: Styx.

Thomas, H.L. 1992. “Historical Chronologies and Radiocarbon Dating.” Ägypten und Levante 3:

143–151.

Van De Mieroop, M. 2007. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–330 BC (2nd edition). Oxford: Blackwell.

Vanstiphout, H.L.J. 2003. Epics of Sumerian Kings. The Matter of Aratta. Writings from the Ancient World. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature.

Westenholz, A. 1999. “The Old Akkadian Period. History and Culture.” In Sallaberger and Westenholz, pp. 15–117.

126

––History and chronology ––

——2000. “Assyriologists, Ancient and Modern, on Naramsin and Sharkalisharri.” In Assyriologica et Semitica. Festschrift für Joachim Oelsner, eds. J. Marzahn and H. Neumann. Alter Orient und Altes Testament, 252, pp. 545–556. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Westenholz, J.G. 1997. Legends of the Kings of Akkade. Mesopotamian Civilizations, 7. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

Wilcke, C. 1988. “Die Sumerische Königsliste und erzählte Vergangenheit.” In Vergangenheit in mündlicher Überlieferung, eds. J. von Ungern-Sternberg und H. Reinau. Colloquium Rauricum, 1, pp. 113–140. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner.

Wright, H.T. 1969. The Administration of Rural Production in an Early Mesopotamian Town. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan.

Wright, H.T. and Rupley, E. 2001. “Calibrated Radiocarbon Age Determinations of Uruk-Related Assemblages.” In Uruk Mesopotamia & Its Neighbors. Cross-Cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation, ed. M. Rothman, pp. 85–122. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Yoffee, N. 2004. Myths of the Archaic State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

127

PART II

SUMERIAN SOCIETY:

THE MATERIAL REMAINS

CHAPTER SEVEN

PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT

IN SUMER AND AKKAD

Jason Ur

The settlement landscape of early Mesopotamia was characterized by great cities that housed great masses of people, kings and priests, and the gods themselves. From the Late Uruk period to the end of the Old Babylonian period (c.3500 to 1500 BC),

Mesopotamian cities contained all of the material manifestations of civilization that have fascinated archaeologists and epigraphers: palaces and temples with traditions of high art, administrative organization, and monumental architecture. These material remains gave clues to social and political institutions and their roles in maintaining urban society. The spatial scale of the settlement, on the other hand, reveals the extent to which these institutions successfully maintained social cohesion among the diverse kin and ethnic groups within the cities. In their absence, settlements inevitably split apart as disputes emerged that could not be resolved except via spatial distance between feuding parties. Such cycles of growth and fission in individual settlements had been ongoing since the start of sedentism in the Neolithic, until the fourth millennium BC.

The Mesopotamian plain witnessed shifting patterns of urban settlement at a time when almost all other human societies worldwide continued to live a village scale existence characterized by frequent settlement fission. The evolution of the urban settlement landscape was not a random process; the shifting constellation of settlements has much to reveal about the underlying social, political, economic, and environmental dynamics. These patterns were not merely reflective of, but became constitutive of, Mesopotamian society. As cities grew, they became meaningful places in the landscape, through association with kings, gods, and events. These enduring symbolic aspects explain why many of the great cities of the fourth and third millennia BC were still densely inhabited and maintained, sometimes at great expense, for several millennia thereafter.

These significant questions of geography and demography require a methodological approach that expands beyond excavation and epigraphy. Excavation opens windows into cities, but these windows have shrunk as archaeologists have appreciated how destructive their methods are, as they have expanded the range of data considered worthy of recording, and as their budgets have shrunk. Even if it were possible to excavate an entire city, these questions would still be out of reach, since urbanism cannot be studied at a single place: it is necessary to understand how the entire settlement landscape evolved, as populations coalesced at some places and abandoned others. For these reasons, Mesopotamian archaeologists were at the forefront of the

131

–– Jason Ur ––

development of survey and remote-sensing methods. When combined with excavation and textual analysis, these extensive methods are powerful tools for reconstructing the evolution of the Mesopotamian settlement landscape.

This chapter reviews settlement patterns in Sumer and Akkad from the end of the fourth to the middle of the second millennium BC. Before doing so, it is necessary to consider some definitions, and to review the strengths and weaknesses of the surveys thus far undertaken on the plain.

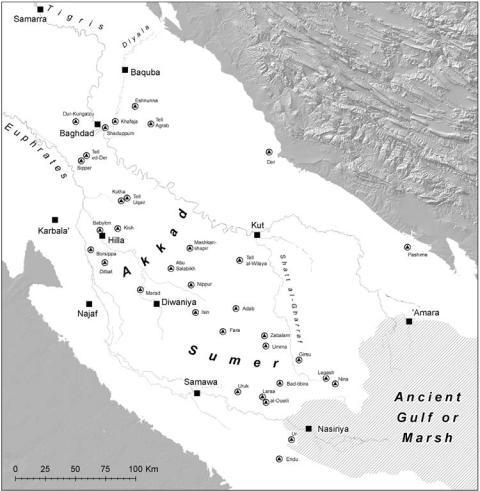

LANDSCAPE AND ENVIRONMENT

The history of settlement on the Mesopotamian plain (Figure 7.1) is inextricably bound to its physical environment (Sanlaville 1989; Verhoeven 1998, Wilkinson 2003: 74–97; Pournelle this volume). The region’s climatic aridity demands that human occupation be tethered closely to surface water sources: the two rivers throughout much of the plain, and marshes in the basins between them and especially at the rivers’ tail ends near the head of the Gulf (Adams 1981: 244). The plain might appear to be a flat and homogenous isotropic plain, but in fact it is a complex and diverse array of elevated river levees, isolated turtleback islands, dune fields, abandoned irrigation channels, and seasonal marshes that is constantly evolving. This landscape variability has implications not only for how its inhabitants adapted to it in the past but also for the elements that have survived for archaeologists to recover.

In the northwestern part of the plain (ancient Akkad), the rivers ran in meandering channels that were prone to shift during floods (Verhoeven 1998). When mapped regionally, settlements often occurred in linear arrays, on account of their close adherence to levees of the rivers and major canals. The Tigris and Euphrates dropped most of their suspended sediments in this upper part of the plain, resulting in substantial aggradation of silts that have buried the earliest sites. Further southeast, in the region between Nippur and the head of the Gulf (ancient Sumer), the rivers adopt more anastomosing or branching patterns. Sedimentation in this region has been less severe, with the result that prehistoric (Ubaid and Uruk) sites are more likely to be visible at the surface than in Akkad. Settlements clustered atop levees here, but the increased presence of marshes resulted in distinct “bird’s foot” deltas (Pournelle 2007:

43–44).

These landscapes were highly dynamic. The rivers themselves were prone to redirect themselves at times of great floods. River diversions could be intentional acts of war that could leave cities or entire regions suddenly without reliable water for irrigation, at which time they would have to be abandoned, or the watercourses restored with herculean effort. Closely related to shifts in the rivers were formation of marshes and steppe regions. In the fifth and fourth millennia, the Gulf extended to the hinterlands of Ur and Uruk, which were surrounded by marshes; gradually this marsh environment was pushed to the southeast. This environmental dynamism must be taken into consideration when evaluating the surviving settlement patterns and their interpretation.

ISSUES AND METHODS IN SETTLEMENT SURVEY

The basic raw data for the history of settlement are site numbers and their sizes, which are best acquired through the techniques of archaeological survey. Survey methods are

132

–– Patterns of Settlement in Sumer and Akkad ––

Figure 7.1 Southern Mesopotamia and adjacent regions. Land over 100 m is hillshaded.

based on two underlying assumptions. Most importantly, past human activities left traces that can be identified via surface observation. If various natural and cultural taphonomic processes can be ruled out, the surface distribution of artifacts and features is assumed to be related closely to the spatial location of ancient activities, most notably sedentary inhabitation. Furthermore, the extent of the surface distribution of artifacts is related to the scale of the ancient settlement and, by extension, its ancient population.

Field survey methodologies evolved, but most Mesopotamian surveys share similar characteristics. The predominant approach is an extensive one designed to recover quickly as many sites as possible over a large area. Known sites (identified from aerial photographs, maps, or local informants) were visited by vehicle, and in places of good visibility, systematic vehicular transects were made on 500 m to 1 km intervals. Cultivated areas were generally avoided, but where they were surveyed, it was necessary

133

–– Jason Ur ––

to follow the lines of canal levees. The surveyors recorded plans of the visible remains, and made opportunistic artifact collections with a particular focus on the edges of sites. Site locations were recorded by sighting on known points by optical compass. Most fieldwork was done rapidly by teams of only one or two archaeologists with an Iraqi government representative.

This methodology, which was employed by almost all surveys of the late twentieth century (Adams 1965; 1981; Adams and Nissen 1972; Gibson 1972; Wright 1981), has strengths and weaknesses. The primary advantage was above all the tremendous geographical extent of coverage, which has placed the Mesopotamian settlement dataset among the largest in world archaeology. Furthermore, it was a necessary concession to the uncertainty of future permits and fieldwork (Adams 1981: 38). For these reasons, most surveys attempted to cover a great area as quickly as possible.

This extensive approach came with some disadvantages, however. Vehicular survey finds the largest sites, but smaller sites can go unseen without a more intensive approach. Individual sites’ sizes were by necessity estimated by impressionistic visual inspection of the surface assemblage and aerial photographs, with the result that shifting patterns of occupation could be overlooked, and small and early occupations might be passed over.

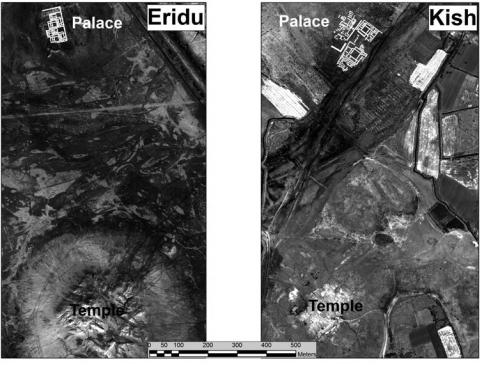

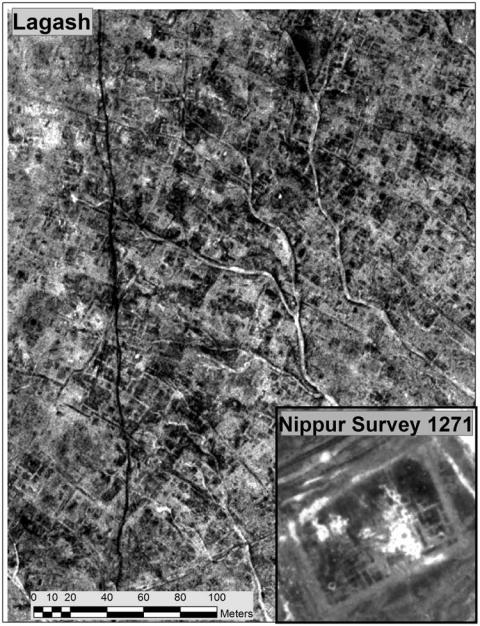

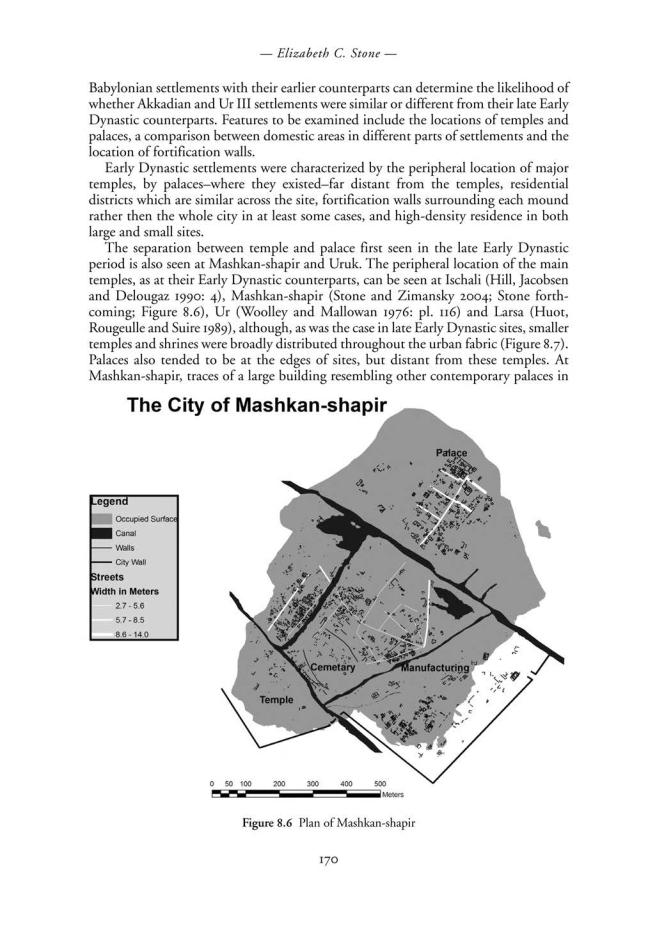

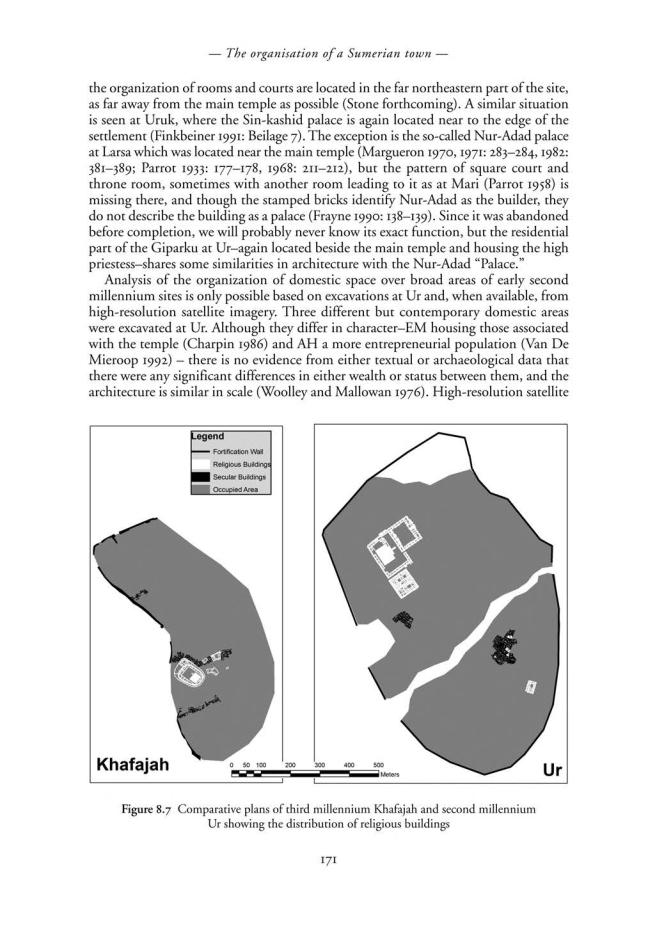

All surveys are by necessity a compromise between spatial extent and intensity of investigation, and Adams and his colleagues were well aware of the ramifications of their methodological decisions. For example, the survey of Uruk’s hinterland was intended as an initial reconnaissance, to be confirmed or corrected by subsequent systematic intensive surveys (Adams and Nissen 1972: ix–x). Unfortunately, no regional projects followed up on the initial surveys, largely because survey permits were not forthcoming (although see Wilkinson 1990 for Abu Salabikh; Armstrong 1992 for Dilbat). Several individual sites, however, have been subjected to intensive systematic surface analysis, most notably Uruk, Mashkan-shapir, Kish, and Lagash (Finkbeiner 1991; Stone and Zimansky 2004; Gibson 1972; Carter 1989–1990). These surveys subdivided the site surfaces into squares or topographical units that were then walked systematically; features and artifacts were mapped, collected, and analyzed by period. Other sites have been analyzed by opportunistically placed sample collection units (e.g., Nippur and Fara – Gibson 1992; Martin 1983). The Mashkan-shapir and Lagash surveys analyzed site functions, based on the distribution of kilns, walls, canals, and manufacturing debris; for most others, the emphasis has been on shifting patterns of growth and contraction as evidenced by the distribution of chronologically sensitive artifacts.

From its inception, the practitioners of survey in Mesopotamia have been concerned not only with sites but also with the landscape between them, especially the rivers, canals, and levees that make agricultural settlement possible. In Sumer, Adams used aerial photographs and site alignments to suggest river and canal alignments and their evolution. The most ambitious project was the multi-disciplinary Belgian and American research around the hinterland of Sippar and Tell ed-Der in Akkad, which involved the synthesis of topography, geoarchaeology, and cuneiform texts (Gasche and Tanret 1998; Heyvaert and Baeteman 2008). A study of channel development around Abu Salabikh also relied on geoarchaeological coring (Wilkinson 1990). Off-site sherd scatters, which are now recognized throughout the Near East and beyond (Wilkinson 2003: 117–118), have only been investigated in the hinterland of Mashkan-shapir (Wilkinson 2004).

134

–– Patterns of Settlement in Sumer and Akkad ––

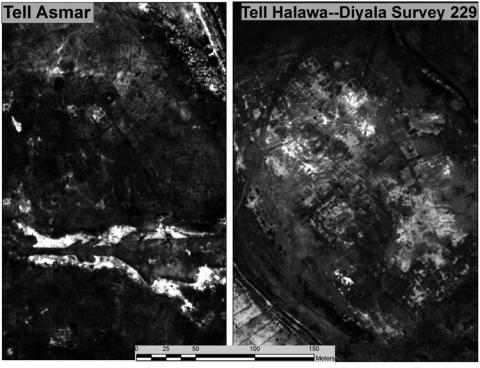

Survey and landscape studies benefit from a remote perspective, and most Mesopotamian research has attempted to include aerial photographs and remote sensing. The surveys of the 1960s and 1970s were allowed limited access to aerial photographs by the Iraqi government, but these were sufficient to identify sites and the traces of relict watercourses (Adams 1981: 28–32). The earliest Landsat imagery was too coarse for site identification but did prove useful for the recognition of abandoned levees (Adams 1981: 33, fig. 6). More recently, SPOT imagery (Verhoeven 1998; Stone 2003) and declassified photographs from the American CORONA intelligence satellite (Hritz 2004, 2010; Pournelle 2003, 2007) has been used to great effect. High-resolution commercial imagery from the Ikonos, DigitalGlobe QuickBird, and other platforms shows great promise (Stone 2007, 2008), as does topographic modeling using data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM; Hritz and Wilkinson 2006).

The great variety of textual sources allow historical geographies to be constructed, and indeed this was the primary aim of the earliest reconnaissances (e.g. Jacobsen 1954). The combination of survey data and textual analysis has been effective in reconstructing patterns of movement and the rural landscape of the third Dynasty of Ur (Steinkeller 2001, 2007). When examined closely, texts can add a human dimension to the shifting patterns of sites; for example, the movement of temple households from Uruk and Eridu to Kish and Ur, respectively, in the Old Babylonian period (Charpin 1986: 343–418), or the resettlement of Akkadian and Hurrian populations, some prisoners of war, in the Sumerian south under the kings of Ur (Steinkeller in press). Texts can also demonstrate abandonments that occur within a single ceramic phase, and are therefore invisible to survey; for example, the progressive abandonment of southern and central Sumer at the end of the Old Babylonian period (Stone 1977; Gasche 1989).

For survey data, chronological analysis is based on surface ceramics. For example, a site with many Uruk ceramics spread over an extensive area is assumed to have been a large settlement in the fourth millennium BC. The great benefit of this method is the incredible abundance of pottery on the surfaces of Mesopotamian sites, but reliance on ceramic chronology poses several challenges. Our ability to subdivide time is linked to the rate of technological and stylistic change in pottery production, but many ceramic types remain in use for centuries. Furthermore, surveyors are dependent on wellexcavated stratigraphic sequences of pottery to which they reference their surface finds. For many periods, such sequences simply do not exist. This problem is compounded in the later historical periods, when epigraphers and art historians prefer chronologies based on political dynasties that are wholly disconnected to patterns of ceramic production.

Evaluation of settlement patterns must include consideration of landscape taphonomy, the processes by which various landscape elements survive, are transformed, or are removed (Wilkinson 2003: 7–8, 41–43). These processes can be natural ones, such as river movements, alluviation, salinization, and wind deflation, or cultural, such as the expansion of irrigation canals and the resulting alluviation. The southern Mesopotamian plain is a palimpsest of many superimposed landscapes which are preserved in an increasingly fragmentary state as one looks further back in time (Hritz 2010; Pournelle this volume).

135

–– Jason Ur ––

HISTORY OF RESEARCH

Near Eastern settlement pattern studies originated with the Sumerologist Thorkild Jacobsen, who developed and applied survey methods on the Diyala plain (1936–1939) in the context of the Oriental Institute’s excavations (see Adams 1965 : viii, 119), and later in Sumer (Jacobsen 1954, 1969). Jacobsen’s work was especially innovative in his concern with spatial patterns of settlements and watercourses, unlike other reconnaissances of the time, which identified sites for excavation (e.g., Roux 1960).

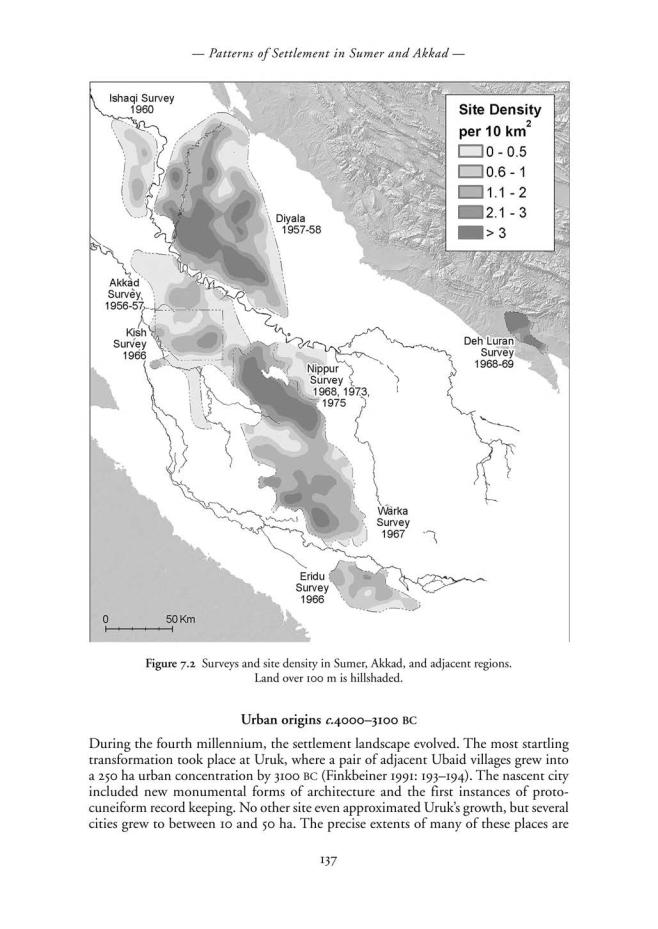

Systematic surveys began in earnest with the work of Robert McCormick Adams in the late 1950s and 1960s. He expanded and systematized the observations of Jacobsen in the Akkad region in 1956–1957 (Adams 1972b) and on the Diyala plain in 1957–1958 (Adams 1965). Surveys in 1966 by McGuire Gibson around Kish and Henry Wright in the Ur-Eridu region (Gibson 1972; Wright 1981) adhered to the methods of Jacobsen and Adams. In the following year, Adams and Hans Nissen surveyed the region of Uruk (Adams and Nissen 1972), after which Adams began a series of survey seasons around Nippur (Adams 1981). After 1969, the Iraqi government ceased issuing largescale survey permits, and with the exception of Adams’ short season around Nippur in 1975, no further extensive reconnaissances have been carried out by foreign archaeologists.

In the 1970s and 1980s, surface surveys focused on individual sites, providing a valuable check on the earlier reconnaissances. Low intensity sampling surveys targeted Fara and Nippur (Gibson 1992; Martin 1983). Intensive full coverage methods were used in the 1980s at Uruk, Lagash, and Mashkan-shapir (Finkbeiner 1991; Carter 1989–1990; Stone and Zimansky 2004). Only in 1990 did regional studies resume (Wilkinson 1990). The first Gulf War put an end to all foreign research up to the present, but Iraqi research led by Abdulamir al-Hamdani between 2003 and 2010 has identified about 1,000 sites in southern and eastern Sumer, particularly in the zones east of the Nippur, Uruk, and Eridu surveys (see al Hamdani 2008).

The efforts of Adams, Nissen, Gibson, and Wright have covered approximately 25,000 square kilometers of Sumer, Akkad, and adjacent regions of southern Mesopotamia, including well over 3,000 recorded sites (Figure 7.2). As a result, the Mesopotamian plains represent one of the benchmarks of global archaeological survey (Ammerman 1981).

THE EVOLUTION OF SETTLEMENT IN SUMER AND AKKAD,

C.3100–1500 BC

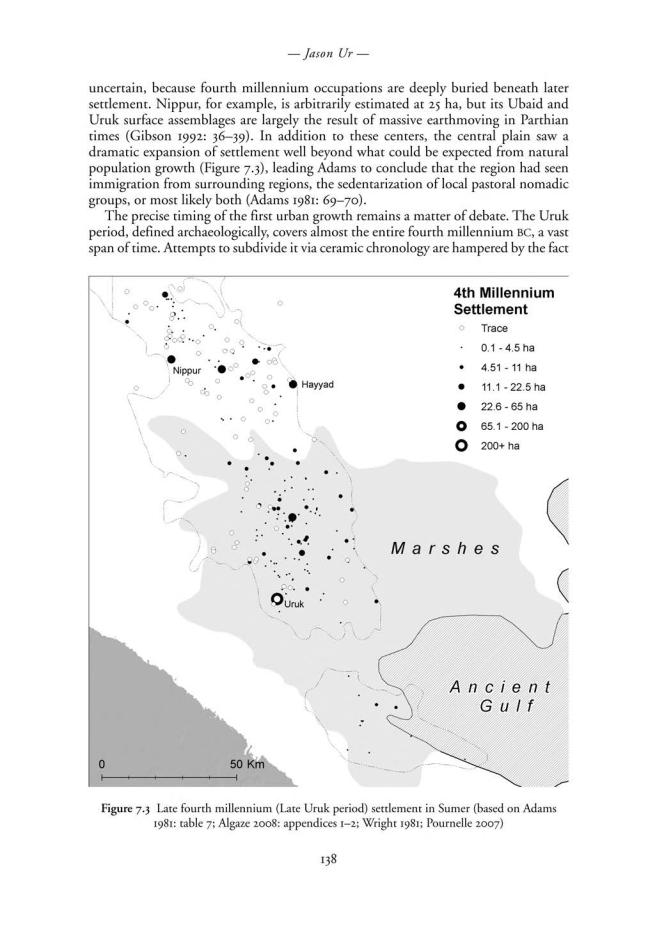

Archaeologically recognizable settlement appeared first on the Mesopotamain plain in the Ubaid period. Sites of that time are mostly small (less than 4 ha), although Ur and Eridu had grown to 10–12 hectares (Wright 1981: 324–325). Patterns of settlement in Akkad are unreliable because of heavy alluviation, but sites appear evenly dispersed in the region of Uruk, perhaps due to a reliance on pastoralism rather than agriculture (Adams 1981: 59). Recent remote-sensing studies have emphasized the marshland context of these earliest southern settlements, which sat amidst marshes on “turtleback” hills of possible Pleistocene date; this model proposes that marsh resources such as fish and reeds sustained the economies of Ubaid villages and also the earliest urban centers of the Uruk period (Pournelle 2003, 2007).

136

–– Patterns of Settlement in Sumer and Akkad ––

that few stratigraphic excavations through the fourth millennium exist, and none were undertaken using modern methods of ceramic seriation or employing absolute dating methods (Nissen 2002: 3–6).

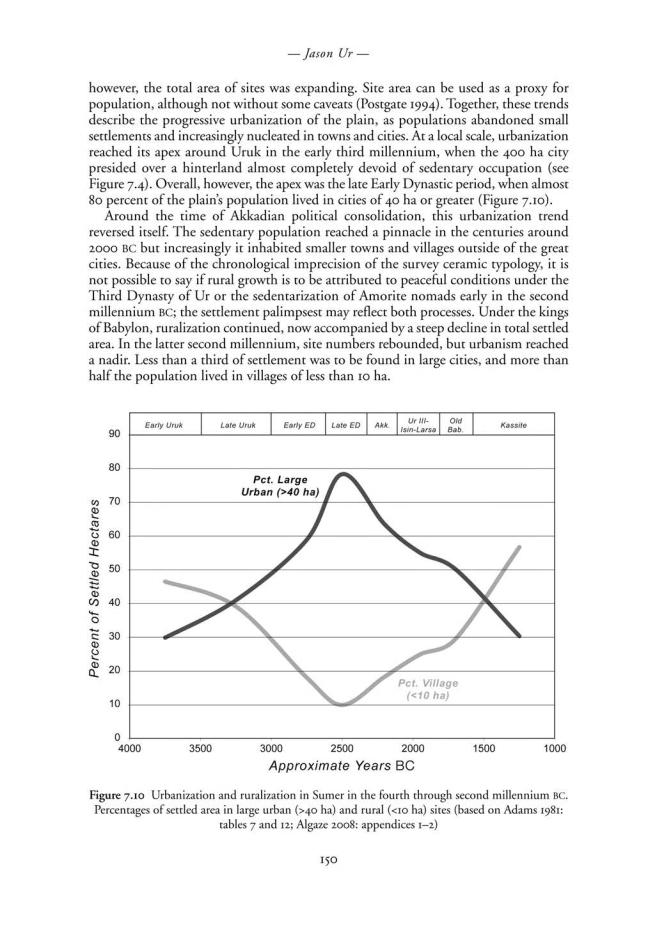

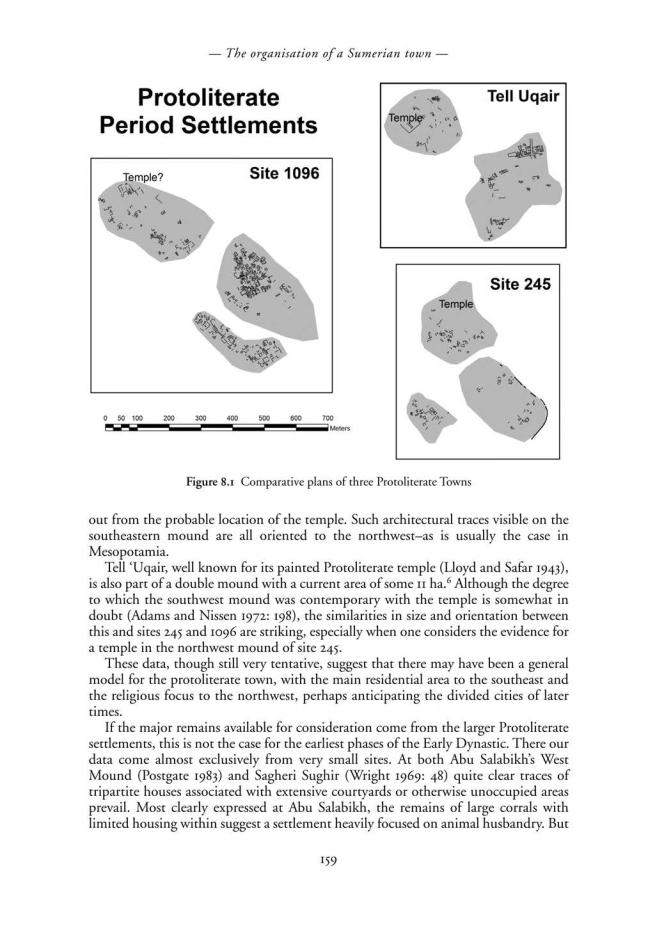

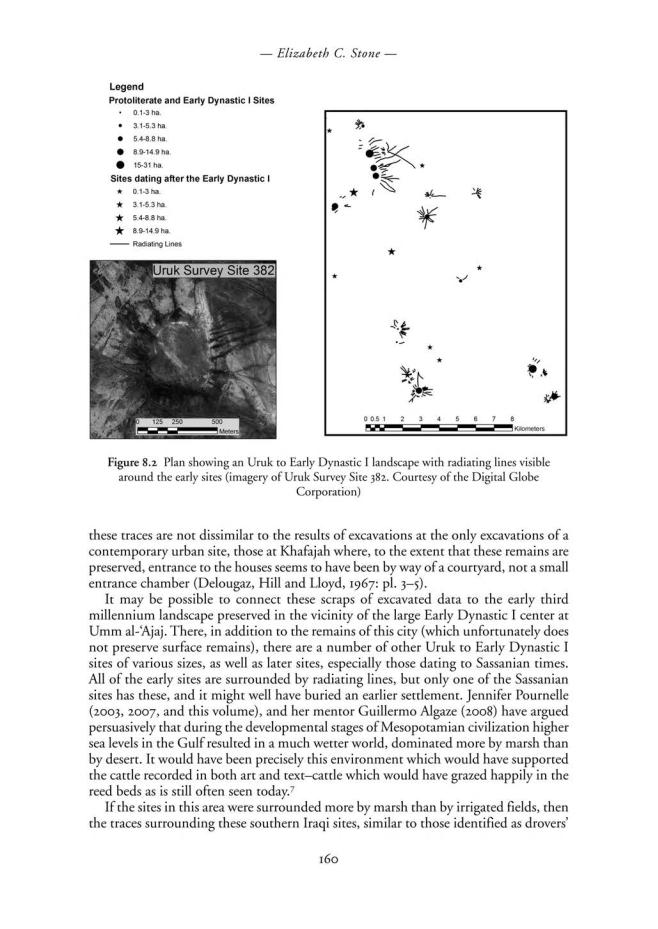

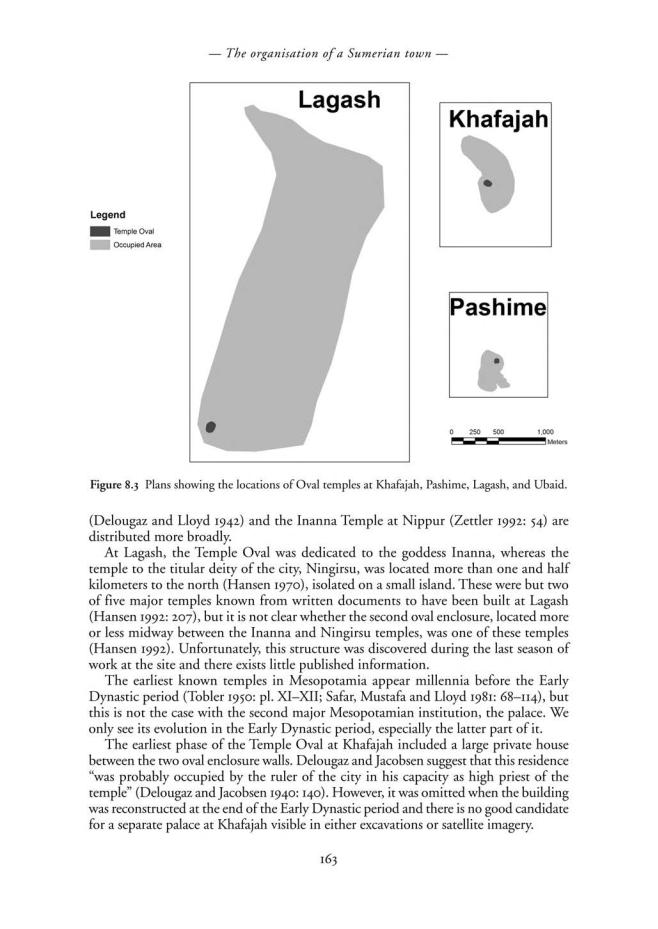

The spatial distribution of Uruk sites is far less linear than in subsequent periods, when linearity is directly related to river and canal alignments (Figure 7.3). For the southeastern part of the plain in particular, this dispersed arrangement may be related to an emphasis on marsh resources in the economy of the time, which beside agriculture and pastoralism represented a “third economic pillar” (Pournelle 2007: 46). Rather than the “pearls-on-a-string” model for later agricultural settlement, this dispersed pattern might result from settlement on elevated turtlebacks and bird’s-foot deltas. Such landforms are common at the ends of river systems that terminate in marshlands. This is at odds with the traditional understanding of Mesopotamian origins in an agro-pastoral economic niche, particularly with the centralization and redistribution of cereals and animal products by nascent temple households (see, e.g., Pollock 1999: 78–80).

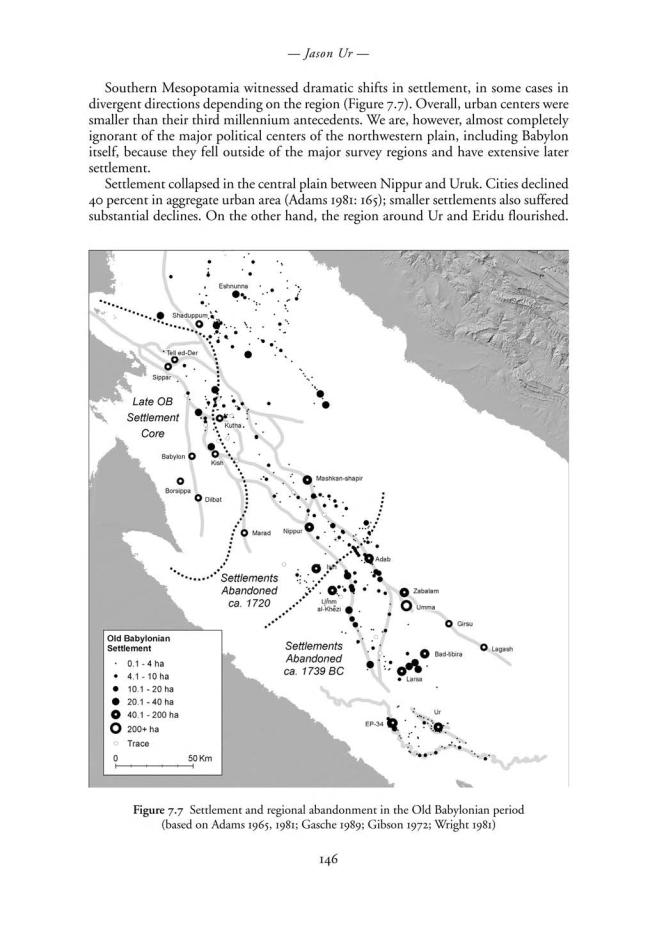

An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, possibility is that the dynamism of the rivers, combined with the inability of human communities to counteract it, forced villages to make frequent relocations. In such a case, the great numbers of sites might result from counting the same populations twice or more in their sequentially occupied settlements.