- •Introduction

- •1 Physical geography

- •5 The Sumerian language

- •6 History and chronology

- •15 Calendars and counting

- •17 Everyday life in Sumer

- •19 A note on Sumerian fashion

- •21 Death and burial

- •22 Sumerian mythology

- •23 Trade in the Sumerian World

- •26 Sumer, Akkad, Ebla and Anatolia

- •27 The Kingdom of Mari

- •29 Iran and its neighbors

- •30 The Sumerians and the Gulf

- •32 Egypt and Mesopotamia

- •POSTSCRIPT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

IRAN AND ITS NEIGHBORS

C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky

The emergence of Mesopotamian civilization, contrary to the manner in which it is typically portrayed, was not a solo performance. It did not appear sui generis, fulfilling its own destiny in the absence of “the other.” From at least the middle of the fourth millennium, Mesopotamia experienced continuous contact with the indigenous cultures of its southern neighbor, the Arabian Peninsula, the northern reaches of Anatolia and the Caucasus, and to the east with the numerous and distinctive cultures of the Iranian Plateau, the Indus Valley, and Central Asia. The nature, chronology, and extent of these cultural contacts form the substance of an extensive literature and debate. This chapter shall emphasize the substance as well as the theory that char-

acterized these contacts during the third millennium.

PROLOGUE

Stretching across the seventh millennium landscape, from the Euphrates River to Central Asia and the Indus River, are distinctive archaeological cultures. Contact and interaction between these largely self-sufficient communities remained a local affair. There is little evidence to support the presence of substantial interaction tying the communities into networks of trade and exchange. That there was communication, however, is supported by the fact that virtually all settlements shared a common technique for the production of pottery (Vandiver 1987) and the manufacture of metal artifacts (Thornton 2009). If important technologies were shared so too was their dependence upon a common subsistence economy: domesticated sheep, goat, cattle, and cereal production.

By the middle of the fifth millennium substantial changes were underway. On the one hand, Mesopotamia was blessed with rich agricultural potential able to support a burgeoning population. On the other hand, it was virtually devoid of natural resources, save for clay, reeds, and some stones. Mesopotamia’s emerging demand for copper, timber, a variety of desirable stones, that is, lapis lazuli, carnelian, turquoise and agate, as well as silver and gold, guaranteed Mesopotamia as an important center of economic demand and the Iranian Plateau as a significant source of supply. By the end of the fifth millennium, the domestication of the donkey facilitated the transport of goods while specialized routes of communication, across the Zagros Mountains, brought Mesopotamia into increasing contact with the east (D. Potts 1999: 10–42; T. Potts 1994:

36–49).

559

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

In Mesopotamia, the Ubaid Culture of the mid-fifth to late fourth millennium experiences a substantial cultural expansion extending from the Arabian Peninsula and the Iranian shores of the Persian Gulf (Masry 1997; Carter and Crawford 2010) to northern Mesopotamia and western Iran. The nature of the Ubaid Expansion, whether resulting from colonization, migration and/or acculturation, are subjects of considerable debate, as is the directionality and timing of its expansion (for a full discussion see the articles in Carter and Philip 2010). The Ubaid Culture is treated in the literature as a foundational stage in the emergence of Mesopotamian cultural complexity, seen as a complex chiefdom or an early state formation.

There is little doubt that Ubaid influences were felt in Iran. In western Iran, the major site of Susa and its Khuzistan neighborhood (Jowi 1 and Bendebal 1) show strong parallels with Ubaid pottery, as do several sites within the Zagros Mountains. Regional differences in settlement organization, architecture, and environment suggest that community organization differed through time and space. Throughout the Ubaid horizon, southern Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran had a two-tiered settlement regime suggesting a pattern of small centers controlling three or four neighboring villages (Wright and Johnson 1975).

The extensive distribution of the Ubaid Culture must be seen within the context of its material presence within local indigenous cultures. Its impact on the political economy within different regions varied from negligible to significant. In Iran it tended to the former rather than the later. It is of importance to point out that the distinctive cultures of the Zagros Mountains and the Khuzistan steppes were, from the earliest periods, profoundly different from that of southern Mesopotamia. Their relationships, as we shall see, were characterized by enmity and outright warfare. In a single instance, and that in the Susa Necropole of southwestern Iran, Ubaid ceramics may be argued as having prestige, even ritual significance (Berman 1994). At Susa toward the end of the fifth millennium, a truly massive platform of two stages was constructed. Adjacent to the platform, a cemetery was excavated containing approximately 2,000 burials and 4,000 Ubaid-like ceramics, fifty-five copper axes and an assortment of other metal objects. A number of seals and sealings with figurative designs were recovered from the burials. From the seventh millennium, seals and sealings were used to secure goods within the household. Commodities were placed in jars or in storerooms, their openings fastened by string and clay which was then impressed by a seal that could be broken only by one having authorized access. Frank Hole (2010: 232) who has studied the monumental architecture and its associated cemetery asks “What does this mean?”:

The evidence suggests that the people at Susa engaged in a massive building campaign that resulted in the great platform which one can plausibly connect to rituals that had become more elaborate and important. These developments occurred during a period of increasing duress, as evidenced by a region-wide decline in settlements, abandonment of regions of Iran and the successive burnings of the buildings atop the great platform.

To Frank Hole (2010: 238) the Susa A platform, “the largest construction of its time in the ancient world,” represents the institutionalization of ritual, the emergence of priestly authority, and their eventual failure in guiding human events. This, in turn, he believes resulted in the destruction of the buildings atop the platform and the

560

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

contemporaneous burial of 2,000 individuals. It is equally plausible that this destructive evidence was brought upon the Susa A community by its Mesopotamian neighbors. This, as we shall see, would be in keeping with third millennium evidence for hostility and conflict, interrupted by periods of rare alliance, that tied Elam, the cultures of the Iranian Plateau, to their neighboring Sumerian city-states throughout the third millennium.

Not all regions of the greater Ubaid horizon experienced the collapse and abandonment experienced in southwestern Iran. Settlements in northern Mesopotamia seem to transition in a seamless manner to a post-Ubaid world while those along the shores of the Persian Gulf, whether in Arabia or Iran, are abandoned. Ubaid and Ubaid-style ceramics are widely distributed but the processes involved in their distribution, the nature of interregional interaction, the varieties of political organization and their socio-economic complexity remain topics for future research. The cessation of archaeological research in southern Mesopotamia and the fluorescence of excavation on large sites in northern Mesopotamia (Tell Brak and Hamoukar) has led some to suggest that centralized states arose, if not earlier, then at least contemporaneously to those of southern Mesopotamia (Gibson and Maktash 2000; Oates 2002).

URUK AND ITS EXPANSION

Following the Ubaid Culture, the Uruk lends its name to both a chronological period, c.4000–3200 BC, and to the largest city in southern Mesopotamia. It was a period of momentous social change. Monumental temples were constructed forming engines of innovation and social change. The temples coincided with the invention of a technology of social control that included writing, standard units of weights and measurements, and the use of seals and sealings for establishing the authenticity of contracts. Temples, under the direction of priests, were supervised by one called an En. Temple institutions directed an administrative bureaucracy of scribes devoted to the recording and control of production, consumption as well as labor, and the redistribution of agricultural produce.

At c.3600/3500 BC a remarkable process was initiated. Uruk settlements were established in distant and foreign lands. Uruk settlements and material remains are found on numerous archaeological sites far distant from Mesopotamia. These Uruk settlements are of considerable size, as at Susa in Iran, some are more modest as Hassek hüyük on the Euphrates River in Turkey, while others are Uruk populations situated within a community of indigenous residents, as at Godin, also in Iran (for a general discussion, chronology, and Uruk expansion sites see Rothman 2001).

What impelled the peoples of southern Mesopotamia to build new towns in foreign lands or settle within foreign communities? The subject has been addressed in several books (Algaze 2005; Stein 1999; Collins 2000) and countless articles. Guillermo Algaze (2005) has been a major architect constructing both hypotheses and explanations of the “Uruk Expansion.” He advances four “causes” that favored the Mesopotamian (Sumerian) “take-off” meant to explain why Mesopotamian civilization holds pride of place.

1. Trade, organized for the “control of coveted resources” (p. 8) involved the import of elite goods, preciosities: metals, precious stones, timber, etc. derived from distant

561

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

peripheries. “Where trade flows, its ramifications in the form of increasing social complexity and urbanism follow” (p. 100).

2. The rich natural landscape, with a variety of complementary ecosystems was the “trigger” (p. 40) that offered environmental and geographic advantages that, in turn, allowed for a “created landscape,” riverine and canal systems that allowed for water transport (being up to four times more efficient than land transport) and communication.

3. New forms of organized labor. Corvée labor attached to central institutions, that is temples, for the construction of monumental buildings, irrigation systems, agricultural projects, warfare, etc.

4. New forms of record keeping with administrative bureaucracies: writing, seals, sealings standard measurements – weights, volume, distance.

Algaze’s “Sumerian take-off” is essentially an economic one. Emphasis is upon cores and peripheries (neighbors). Mesopotamia is portrayed as a dominant core that is extractive, controlling, colonizing, and exploitative of its underdeveloped, subservient, and manipulated neighbors. The establishment of Uruk colonies in northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Iran “may be conceptualized as unwittingly creating the world’s earliest world system” (p. xv). World Systems Theory (hereafter WST) takes its lead from Immanuel Wallerstein’s (1974) study of the emergence of capitalism in the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries. It has had a major influence upon archaeologists working in different parts of the world (Kardulias 1999). WST insists upon three assumptions, none of which are applicable to the Bronze Age of the Near East:

1. The core dominates the periphery [read neighbors], be it by organizational efficiency, military means, or ideological agency.

2. The core exploits the periphery by asymmetric trade; the extraction of valuable resources from the periphery by exporting cheap goods from the core.

3. The politics of the periphery are structured by the cores’ organization of trade and exchange.

Algaze’s faith in WST is firmly alleged but when considering the evidence weakly demonstrated. As Marshall Sahlins (1994: 412–413) has observed, in denying agency to its neighbors “world systems theory becomes the superstructural expression of the very imperialism it despises.” For Algaze the periphery, be it Anatolia, Iran, or the Arabian Peninsula, is a benign entity, neither described nor explored, an ill-defined entity whose presence is to serve southern Mesopotamia’s colonization and quest for resources. In discussing core–periphery relations, Mario Liverani (2006: 69–70) is more to the point:

The [Mesopotamian] population supports itself with agro-pastoral resources, on which inter-regional exchange has no influence . . . It is certain that, in the period of concern here [the Uruk] the economic exploitation pertained to resources that were of secondary character only [elite goods] . . . it contributed to an increase in the local socio-economic stratification and it strengthened the elite’s hold over the general population.

562

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

Far more preferable, and consistent with the evidence, are the views of Nick Kardulias (2007) and Gil Stein (1999). Kardulias writes of a “negotiated periphery” in which the periphery negotiates its own rules for inclusion or exclusion from a core. Stein views the Uruk Expansion as having nothing to do with colonization, domination, and asymmetric relations but as independent enclaves in which the “foreigners were an autonomous diaspora rather than a dominant colonial elite . . . The Mesopotamian and Anatolian [and, one might add, Iranian] communities produced, exchanged, and consumed goods with their own encapsulated social domain” (Stein 2002: 58). What matters most in these distinctive and distant Mesopotamian foreign enclaves is not the dominance and exploitation by a Mesopotamian core over a distant neighbor but the existence of a political, economic and social connectivity; that is, the recognition of the existence of numerous independent and interdependent cultures in which Mesopotamia, beginning in the Ubaid period, is but one actor among many that were in contact with “the other.”

Such contacts had their own rhythm. After 3100 BC, Uruk cultural remains all but disappear from foreign lands. Was this the result of assimilation? Voluntary abandonment? Or conflict? Each has its advocate but none are persuasive. The demise of the Uruk Expansion goes unexplained. In northern Mesopotamia, the indigenous communities, introduced to the technology of writing by Uruk immigrants, do not adopt its technology for another 500 years.

There is another significant migration of foreign peoples into Anatolia, northern Mesopotamia, and Iran. They may, in fact, be implicated in the withdrawal of the Uruk peoples from the north. The Kura–Araxes Culture from the Caucasus takes its name from the Kura and Araxes Rivers in Georgia (Palumbi 2008). This pastoral nomadic culture, with its highly diagnostic burnished red-and-black ceramics, domestic architecture, characteristic hearths, and superb metallurgical inventory, is contemporary with the Uruk Culture. The Kura–Araxes Culture can be identified on numerous sites in northwestern Iran where the settlements of Godin IV, Yanik Tepe, and Geoy Tepe (see the articles in Lyonnet 2007) and the burial tumuli of Se Gardan (Muscarella 1973) have been excavated. Its most southern extension reaches northern Palestine where the pottery is known as Khirbet Kerak (Amiran 1968). The nature and impact of the Kura–Araxes cultures in these regions are the topic of considerable recent research. In Anatolia, the arrival of the Kura–Araxes at the site of Arslan Tepe coincides with both its destruction and the disappearance of the Uruk Culture (Sagona and Zemansky 2009; Kohl 2005: 86–102). Similarly, the abandonment of the Uruk community at Godin Tepe coincides with the arrival of these Transcaucasian settlers. Can the pastoral nomadic peoples of the Caucasus be implicated in the disturbances that led to the abandonment of Uruk influence in the north? Ongoing research in Anatolia and northern Syria may answer this question.

Finally, with regard to the Uruk Expansion only within one community, and that an extremely significant one, Susa, in southwestern Iran, can one argue for an Uruk settlement that profoundly influenced its indigenous inhabitants. The Uruk settlement in Susa was directly followed by the Proto-Elamite culture. The Proto-Elamites adopt many of the material attributes of the Uruk Culture and transform them to their own purpose and style, namely, writing, mathematical constructs, seals, specific ceramic types, and units of measurement.

563

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

THE PROTO-ELAMITES AND THEIR EXPANSION

In the early years of the twentieth century more than 1,600 tablets with distinctive signs were recovered from Susa. These Proto-Elamite texts were initially thought to be related to the later Elamite language. Today their linguistic affiliation remains uncertain although its derivation from the earlier cuneiform of the Uruk period is well established (Damerow and Englund 1989). The Proto-Elamite texts, like their Mesopotamian counterparts, record administrative transactions mirroring the book-keeping techniques and numerical systems of their Uruk neighbors. Jacob Dahl (2009: 28) writes “It is at present only possible to distinguish very basic semantic categories in the signary, such as numerical signs, owner signs, object signs, and signs used in a complex way to describe owners.” Presumably, as in Mesopotamia, the “owners” are those individuals or institutions involved in recording the production, consumption or redistribution of the goods, land, or labor being recorded.

The Proto-Elamite tablets, dated between 3400 and 2900 BC are but one, yet, the most characteristic signifier, of this culture. Specific pottery types, cylinder seals, and sealings identify their presence while the size of bricks are a common feature of ProtoElamite administrative structures. It is assumed that the Proto-Elamite Culture (hereafter P-E) emerges in southwestern Iran where its presence is recorded on two of the regions’ largest sites: Susa and Choga Mish. At Susa levels 18–22 were settlements (colonies?) of the Uruk Culture and were succeeded directly by the P-E levels 17–14 (LeBrun 1978; Canal 1978).

One of the most characteristic, and shared, pottery types of the Uruk and P-E periods are referred to as “bevel-rim bowls” (hereafter BRB). This unattractive, yet functional, pottery is handmade and/or mold made, chaff tempered, characterized by a highly porous fabric, and fired at low temperatures. In discussions concerning the function of the BRBs, two hypotheses dominate. Hans Nissen was first to advance the hypothesis that the BRBs were used as a standard measure for distributing rations (grain) to workers. Alternatively, their similarity to Egyptian bread molds suggest a similar function for the BRB (for an excellent review on all matters and references pertaining to the BRB see Potts 2000). The BRB has been recorded on over 100 different sites on the Iranian Plateau. The expansive distribution and the presence of P-E tablets, seals, and sealings on numerous sites throughout Iran brings us to a consideration of the P-E Expansion.

While many trees have been lost to the production of paper for writing on the Uruk Expansion, the slightly later and even greater geographical expanse of the P-E Expansion is all but ignored. This is in keeping with the Mesopotamocentric perspective of Near Eastern archaeology wherein Mesopotamian concerns dominate the literature. Assuming that archaeologists are correct in their belief that southwestern Iran (Khuzistan: Susa and Choga Mish) was the origin of the P-E, its characteristic material culture is subsequently found on sites distributed across the Iranian Plateau (Tepe Sialk, Malyan, Tal-i Ghazir, Tepe Yahya, Tepe Sofali, Tepe Hissar, Shahr-i Sokhta, Tepe Godin) with BRBs extending to distant Pakistan Baluchistan (Benseval 1997; LambergKarlovsky 1978). The recent excavations at Tepe Sofali on the Tehran plain contains an Uruk settlement “followed by settlement continuity in the Proto-Elamite period and then deserted” (Yousefi and Hessari 2008: n.p.). To date, over 100 Proto-Elamite tablets have been recovered from Tepe Sofali. The authors write “Certain it is that at Tepe

564

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

Sofalin there is continuity in the use of texts, beveled-rim bowls, standardized units, sealings, and cylinder seals from Late Uruk to the Proto-Elamite Period.” Also, the recent excavations at Tepe Sialk uncovered a Late Uruk (3750–3350 BC – Sialk III) settlement indicating Mesopotamian contact with the central plateau. The excavation of Late Uruk metallurgical installations, involving the production of silver, gold, lead, and copper, suggest the initiative for Uruk contact. Although no administrative building was uncovered, the presence of cylinder seals and sealings suggest an administrative centralization within a “proto-urban social structure” (Nokandeh 2010).

The “cause(s)” of the P-E expansion, even if seldom addressed, mirror those for the Uruk Expansion: trade and the exploitation of distant resources. The exploitation of metal resources at Tepe Sialk, the transshipment of lapis lazuli from Shar-i Sokhta, the presence of elaborate carnelian beads of Indus manufacture, or the production of carved chlorite vessels in southeastern Iran, all representative of artifacts recovered from tombs and temples in Mesopotamia, are frequently cited as evidence for Mesopotamia’s reliance on Iran for its acquisition of precious goods. The majority of P-E sites, however, lack evidence for the production of commodities and are not adjacent to significant resources. There is, in fact, little, if any, evidence to support the notion that the Proto-Elamite world was directed by a centralized authority or represented a solitary state. Harriet Crawford (1973) has drawn our attention to “invisible exports,” commodities that do not survive the archaeological record. Their existence is undeniable and of significance, but one wonders what they might have been to fuel so extensive a migration, colonization, and distribution of either the Uruk or the P-E culture communities.

It is instructive to review the nature of the P-E tablets at Tepe Yahya so productively examined by Peter Damerow and Robert Englund (1989). The large bulk of the tablets (twenty-one of twenty-seven) are concerned with the measurement of quantities of grain. Damerow and Englund’s summary (1989: 62–63) remains the best to date on the nature and function of P-E tablets, and may, with little variation, apply to other P-E settlements on the Iranian Plateau.

1. “The similarity of the proto-elamite texts from these outlying sites to those from Susa seems, in fact, less suggestive of political or economic control of these settlements by interests centered in or around Susa – or for that matter any other external center

– than of the mundane functioning of more or less independent economic units.” 2. “The texts, so far as we have been able to classify them, record however the dispensation of product from agricultural activity, in particular the rationing of quantities of grain to presumable workers under the direction of household administrators, and possibly the disbursement of grain for the purpose of sowing, as we think, rather unimposing fields. The level of these administrative notations, the size of the recorded numbers of animals and humans and the measures of grain, are without

exception entirely within the range of expected local activity.”

3. “There was no archaeological evidence in Yahya suggesting that this apparent foreign element had assumed administrative control of the settlement by force might be indicative of a peaceful coexistence between an indigenous population and administrators of foreign origin.”

4. “The complete absence of references in these texts to the exploited resources of the regions, in particular of metals or stone, suggested that such exploitation, if at all

565

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

recorded, will have been secondary to primary agricultural activities in the respective settlements.”

5. “Material remains and to a substantially lesser extent early texts inform us that such societies, which may themselves be termed ‘archaic’, operated at a stage well removed from that of so-called primitive cultures. The mere fact of a centralized administration, be it local or regional, as well as the quantity of goods and workers registered in archaic texts document, in our opinion, an at least inchoate form of class division into a functioning administrative elite and laborers, probably with a concomitant shift of ownership of in particular productive land to a small group in the community. This more advanced organization replaced tribal or simply familial organization in village settings.”

We are left to wonder whether there ever was an Uruk or Proto-Elamite Expansion or whether there was a wholesale adoption, emulation and assimilation of a social technology, one that used tablets, incorporated an administrative bureaucracy, with distinctive styles of cylinder seals, BRBs, and numerical systems. To what extent could the invention of this social technology, devoted largely to serve the needs of an elite, be the movement and adoption of concepts and their underlying social structures rather than the large scale migration of people?

The settlements of the P-E, like those of the Uruk Expansion, did not endure. Their chronologies differed dramatically. While the Uruk Expansion appears to be a process that unfolded over the course of millennium, the Proto-Elamite Expansion endured from 3300 to 2900. The social experiment, cast over the Iranian Plateau, collapsed. As the Iranian Plateau reverted to its distinctive regional cultures literacy disappeared not to re-emerge for a millennia. The distinguished art historian Pierre Amiet (1993: 26) is concise: “The proto-Elamite civilization collapsed as from a single blow, without any previous sign of decadence . . . the proto-Elamite highlands went over completely to a nomadism that is imperceptible in the archaeological record, Susa fell back again for many centuries into the Mesopotamian orbit.” In the next section, we will have more to say about the role of pastoral nomadism.

CULTURE, ETHNICITY, AND NATION

The history of relations between the peoples of Mesopotamia, the Sumerians, and the Iranian Plateau, the Elamites, is best derived from the written texts of the third millennium. Referring to place and people with a single term both simplifies and falsifies. Assyriologists remain uncertain as to the language(s) of the earliest texts. There is a greater consensus that the earliest texts of southern Mesopotamia are in Sumerian rather than that the Proto-Elamite texts are Elamite. Sumerian and Elamite are extinct linguistic families without any modern descendants. We must appreciate that in both regions there was a mosaic of linguistic representation. In Mesopotamia there was Sumerian, Semitic, and even Indo-European languages spoken in the north, while the nature of languages spoken in the Arabian peninsula and on the Iranian Plateau remain unknown. By the end of the third millennium there is even an inscribed cylinder seal depicting a translator from the Indus Civilization, with entourage, sitting on the lap of a Mesopotamian King (Possehl 2002, for illustration see Lamberg-Karlovsky 1981: 390). Geographic and cultural diversity complemented this linguistic mosaic. Although

566

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

Mesopotamia is referred to as the ‘lowlands” in contrast to the “highlands” of the Iranian Plateau, both have a considerable diversity of climate and environment.

In the first half of the third millennium, Mesopotamia consisted of independent city-states each dominating a hinterland of towns and villages. Internal competition between independent city-states often resulted in warfare while foreign campaigns against the Elamites offered the promise of wealth and prestige within their homeland. Initially “Sumer” and “Elam” were neither “nations” nor “states.” Elam consisted of a loosely, and poorly understood, confederation of distinctive cultures and tribes inhabiting the Zagros Mountains and beyond. Whether it be Sumer or Elam, integration never fully replaced fragmentation. Elam designated the Iranian highlands and never referred specifically to a city, that is, Susa or a region Khuzistan (Susiana). Dynastic transformations negated issues of decline and fall. Piotr Michalowski (2008: 112–113) is a good guide to Elam’s definition:

In the language of thirdand second-millennium Mesopotamian inscriptions and literary texts, Elam seems to refer to the southeastern half of the highlands (Zagros Mountains) bordering on Mesopotamia, while Subir covers the northeastern part. This is a very general notion and cannot be pinpointed on the map . . . In all these instances, Elam is a general geographical term and does not refer to a political entity

. . . It may be that most people in the general area that Mesopotamians referred to as Elam spoke versions of the language we call Elamite, but at the same time it is likely that the general area of Subir was home to a variety of tongues, including Gutian and Lulubean, not to mention Semitic . . . by Old Babylonian times (mid second millennium) the semantic scope of Elam had changed: it was now a political as well as geographical term and it included Susiana.

Throughout the third millennium, hostility and warfare was the leitmotif that characterized the relations between Sumer and Elam. This would have had a debilitating impact on overland trade crossing the Iranian Plateau. Hostile relations may explain why there is more evidence for maritime trade uniting the Indus Civilization, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula than the more restricted overland trade between these regions and the Iranian Plateau (Lamberg-Karlovsky 1996: 73–108; Possehl 2002: 215–236). The evidence, or “cause” for the hostility between Sumer and Elam must be sought in the cultural divide that separated the two. Their political organization (city-state vs. tribe), their subsistence pattern (agricultural villages vs. pastoral nomadism), and their environment (alluvial floodplain vs. mountain highlands) offered distinctions with real difference. The cultural boundary that separated the two can be traced back to the sixth millennium (Oates and Oates 1976; Mortensen 1974). Pastoral nomadism was a dominant subsistence pattern in western Iran already in the sixth millennium. The presence of pastoral nomads in the sixth millennium is demonstrated archaeologically at Tepe Tula’i in northern Khuzistan and at Hakalan and Parchineh in Luristan (Hole 2004; van den Berghe 1987).

By the late third millennium, archaeological cultures are complemented by historical texts that refer to the Guti, Lululubi, Simurrum, Shimashki, Harashi, Tukrish, Marhasi, Anshan, Hurti, Kimash, and Aratta as inhabiting the Zagros and beyond. The geographical positioning of these groups and their relations to Mesopotamia is a constant theme within the archaeological and textual literature (for a comprehensive

567

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

treatment of Elam see D. Potts 1999). Recently, Abbas Alizadeh (2006, 2010) has offered an insightful model for the emergence of the Elamite world. To inform the archaeological record, Alizadeh avails himself of modern ethnographic as well as ethnoarchaeological data. The role of pastoral nomadism and their antagonistic relations with centralized states is his central theme. It is an old one. The resistance to central authority by the tribes of the Zagros is also a persistent theme in early travel literature, that is, Henry Layard’s (1887) travels through the Zagros in 1840–1842.

Alizadeh’s model, based upon the archaeological and textual record:

revolves around the idea that social hierarchy could develop in the Zagros valleys with arable land and enough precipitation for dry farming and that circumscribed conditions of these valleys would encourage the expansion of the political and economic base of the tribal khans to include the demographic and economic resources of the lowlands [southwestern Iran: Susiana]. Successful unification of the highland and lowland resources as well as easily defensible heartlands in the mountains, control of major trade routes, and the preservation of a tribal structure with strong bonds between rulers and the ruled created a series of durable and strong states that eventually gave rise to the historical “federative” state of Elam . . .

highland pastoralists were in a position to dominate the lowlands [Susiana] and create a diversified political economy that included farming, herding and trade . . .

the gradual development of state organizations in the early fifth millennium, such as an increase in regional population, improvement of agricultural techniques, the development of local elites, increased demand for goods not locally available, increase in overlapping territories and hostile contact, ambitious khans vying for more power and expansion . . . culminated with the integration of the lowlands and the highlands enabling the highlanders to establish a durable and powerful state that under different dynasties lasted for more than 2000 years.

(2010: 360, 375)

Almost fifty years ago Robert Adams (1962: 115), with far less information at hand than available to Alizadeh already observed that:

Elamite military prowess did not derive from a large, densely settled peasantry occupying irrigated lowlands in what is loosely considered the heart of Elam. Instead, the enclave around Susa must have been merely one component in a more heterogeneous and loosely structured grouping of forces.

The first half of the third millennium experienced endemic competition for an elusive hegemony among the Mesopotamian city-states as well as periodic confrontations with Elam. Half a millennium of periodic conflict resulted in the supremacy of Sargon’s unification of Mesopotamia (2350 BC). It was not to last. Sargon’s empire was to endure for only six generations before succumbing to defeat by the highlanders from the Zagros. For the next 1,500 years Mesopotamia and Elam experienced an oscillation between unification and fragmentation. The single constant was conflict and warfare. Textual evidence now dominates our understanding of the relations between Sumer and Elam.

568

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

SUMER AND ELAM IN THE TEXTS

Textual knowledge is assymetrical; meaning that the texts of the third millennium come exclusively from Mesopotamia, their neighbors remain illiterate. The texts are referred to as being “historical–literary” in which mythology and propaganda are mixed with historical “facts,” which themselves require careful scrutiny (Michalowski 1992,

1995; Liverani 2006, 2004).

One of the most famous such texts is “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta” (Vanstiphout 2003; Cohen 2000). Enmerkar, the ruler of Uruk, is engaged in negotiations with the ruler of Aratta who lives far to the east. Enmerkar wishes to obtain precious stones, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and other preciosities, to embellish his temple of Inanna. Messengers go back and forth. Favorable negotiations bring a consignment of precious goods to Enmerkar in return for a donkey caravan of grain. The negotiations include a battle of wits between Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, a timeless motif between contending kings. The epic contains fantasy, riddles, legend, and myth wrapped around elusive kernels of history from which many extract interpretation and models of economic relationship (Kohl 1973). The epic poem is taken to illustrate: Sumerian supremacy over foreign countries; the importance of its principal exports: wheat, manufactured goods, and textiles; the invention of long distance trade, and, most significantly, writing. In fact, third millennium Mesopotamian texts involving long distance trade are exceedingly scarce. Mesopotamian trade was largely restricted to exchange between city-states involving textiles, fleece, grain, perfumes, fats, and dried fish. Trade in luxury commodities as gold, silver, lapis, carnelian, in general all luxury goods, were under the control, and for the consumption of the elites.

The texts afford us glimpses of the political relatons that characterized Mesopotamian–Elamite relations. Below we list Sumerian Kings, dates, and their relationship with their Elamite counterparts (adopted with alterations from Giovanni Pettinato 1972).

Enmebaragesi |

2680(?) |

Mentioned in the Sumerian King |

|

|

Lists as the King of Kish, during its |

|

|

First Dynasty, who reined for 900 |

|

|

years and as “the one [who] broke the |

|

|

weapons of Elam.” |

Elamite Dynasty |

2600–2500(?) |

The city of Ur was defeated. The |

of Awan |

|

Sumerian King list states it “kingship |

|

|

taken to Awan’” (Jacobsen 1939: 95, |

|

|

iv, 117). |

Second Dynasty of Kish |

2550 |

Awan was defeated its kingship taken |

|

|

to Kish. |

Elamite Dynasty of |

(?) |

Power shifts to Elamites. |

Hamazi |

|

|

Lugalannemundu of Adab |

(?) |

Warred with Dynasty of Marhashi |

|

|

and Gutium and received tribute |

|

|

from a governor of Elam. |

569

|

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky –– |

|

Eannatum |

2470 |

Conquered Elam: “Elam in her mountain was |

|

|

thrown down.” |

Enetarzi |

2400/2370 |

Elamites plunder the city of Lagash and are |

|

|

defeated. |

Sargon of Akkad |

2340–2284 |

Unifies Mesopotamia. Conquered Elam and |

|

|

its allies Marhashi, Anshan, and Tukrish. |

Rimush |

2283–2275 |

Revolt suppressed in Mesopotamia. |

|

|

Conquered Barahshum, Zahara and Elam. |

|

|

“Rimush, king of the totality, rules now |

|

|

Elam.” |

Manishtusu |

2274–2260 |

Campaigns against Elam. |

Naram-Sin |

2259–2223 |

Major buildings constructed at Susa; Elam |

|

|

reduced to a vassal state. |

Sharkalisharri |

2222–2198 |

Fights defensive battles against Elamites led |

|

|

by Puzur-Inshushinak, King of Awan, and the |

|

|

Elamite confederation. |

Gudea of Lagash |

2144–2124 |

Defeats Anshan and brings Elamite craftsmen |

|

|

to Lagash. |

Utu-Hegal |

2116–2110 |

Guti defeated. Elam declares independence. |

Shulgi |

2093–2046 |

Diplomatic alliances: in eighteenth year of |

|

|

reign married his daughter to King of |

|

|

Marhasi, thirty-second year marries daughter |

|

|

to King of Anshan. After ten campaigns in |

|

|

year forty-five of his reign he conquers |

|

|

Shimurrum and Lullubum. His three-year |

|

|

campaign against Kimash and Hurti secured |

|

|

for him the Great Khorasan Road and an |

|

|

access route to Babylonia. |

Shu-Sin |

2036–2928 |

Marries his daughter to Prince of Anshan. |

|

|

Campaigned against the Elamites in northern |

|

|

Zagros. |

Ibbi-Sin |

2027–2003 |

Last of the kings of the Ur III dynasty. Elam |

|

|

and Shimashki unite to plunder Ur: “Hills of |

ruin and places of desolation.” Ibbi-Sin carried off in chains to Anshan. Almost certainly it was King Kindattu of Elam who was responsible for the destruction of Ur and the end of Ur III empire.

The Ur III empire was founded by Ur-Namma whose contemporary and protagonist was Puzur-Inshushinak the governor of Susa and “General of the land of Elam.” Although the Elamites contested the Akkadian Dynasty prior to the founding of the

570

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

Ur III period, it was Puzur-Inshushinak whose conquests within the Iranian highlands consolidated an Elamite confederation and allowed for his conquest of northern Babylonia and the city of Akkade, capital of the Akkadian Empire. Following PuzurInshushinak’s capture of Akkade he bestowed upon himself the title “powerful one” and “ruler over the four quarters of the world.” The Akkadian king Naram Suen was the first Near Eastern monarch to adopt this title. Puzur-Inshushinak’s assumption of this title clearly suggest the transfer of power to the hands of the Elamites. To those titles he added the ancient and prestigious title “King of Awan,” the highest distinction an Elamite could aspire to. Awan’s location remains unknown.

Of the numerous constituencies that formed the Elamite confederation we conclude with a discussion of two: Marhasi and Simashki. The location of these two polities is subject to contending views while both regions are targets of recent archaeological campaigns.

MARHASI/PARAHSHUM

The name Marhasi in Sumerian, Parahshum in Akkadian, appears in the Mesopotamian texts from Akkadian to Old Babylonian times, c.2300–1700 BC. They inform us that the Akkadian kings Sargon and Rimush conquered Marhasi, that messengers from Marhasi were dispatched to Ur, and that Sarkalisharri, when crown prince, traveled to Marhasi. Significantly, Shulgi, pre-eminent King of the Ur III empire, gave his daughter in marriage to the Marhasian ruler, thus, cementing an important and enduring political alliance. Marhasi was the source of plants and animals (dog, sheep, bear, monkeys, elephant, and zebu) and certain stones sent to Mesopotamia (Steinkeller 1982; D. Potts 2002). Although many Marhasian names are Elamite, the texts indicate that it lay beyond the lands of Elam. Its location is contested. Given the identity and distribution of the animals, Françoise Vallat (1985) places Marhasi in Baluchistan, while Steinkeller (1982, 2006) positions it in southeastern Iran, and Francfort and Tremblay (2010) place it in Central Asia. Both southeastern Iran and Central Asia are theaters of recent, and highly significant, excavations. In southeastern Iran, two excavation programs are of importance. Massimo Vidale (personal communication) has been excavating Mathoutabad, a site with long fourth and third millennium occupational sequences with numerous bevil-rim bowls that indicate a Proto-Elamite presence. Yosef Majidzadeh has been excavating the nearby site of Konar Sandal. Both sites are situated in the Jiroft Valley in the proximity of the Halil Rud River where preliminary surveys indicate the presence of at least 300 prehistoric settlements. Beginning in 2000, the Jiroft was the scene of illicit digging involved in the looting of a large cemetery. Hundreds of beautifully carved and inlaid chlorite bowls were recovered (Madjidzadeh 2001). Identical decorated bowls, many in the process of manufacture, were recovered in the excavations of nearby Tepe Yahya (Lamberg-Karlovsky 1988). These chlorite bowls are referred to as having an ‘Intercultural Style” for they have been recovered on numerous sites in Mesopotamia, islands of the Persian Gulf, and in the Indus Valley. Certain it is that they are an indigenous product of southeastern Iran. Recently, Steinkeller (2007, n.d.) suggests that the word duh-shi-a mentioned in the texts as a stone coming from Marhasi, refers to chlorite. As the carved bowls of the “intercultural style” were manufactured of chlorite, the identity of duh-shi-a as chlorite takes on added significance. Excavations

571

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

at Konar Sandal recovered dozens of illicitly excavated decorated chlorite bowls, monumental architecture, including evidence for the origin of the “ziggurat” (Vallat 2003), seals and sealings, some with Mesopotamian motifs, an important sequence of pottery, and controversial tablets (Madjidzadeh and Pittman 2008). Of special interest, and of questionable nature and context, is the recovery of four “documents” from Konar Sandal. These “texts” cannot be readily paralleled with either the Proto-Elamite signary or the millennia later Linear Elamite texts. A preliminary analysis has been undertaken by Françoise Desset. It is argued that the “texts” represent a wholly new type (language?) called “eastern script” by Steinkeller, “kermanite” by Vallat, and “geometriform” by Desset (françoise.desset@wanadoo.fr).

Certainly the importance of the kingdom of Marhasi, as indicated in the texts, is complemented by the distinctive and complex culture(s) recovered by archaeologists working in southeastern Iran. Yet, as indicated above, the geographical location of Marhasi remains contested. Textually, Marhasi is the single most documented foreign country in contact with Mesopotamia. In the Akkadian period, King Rimush claims that his military defeat of Marhasi removed its “roots ‘ from Elam, implying that Marhasi and Elam were separate entities. Another text refers to Marhasi as a neighbor of Meluhha (the Indus Civilization).

SHIMASHKI

Piotr Steinkeller (1982) has convincingly demonstrated that the ethnicon “Su-People” is an alternative writing for the geographical term “Shimashki,” referred to in the texts of the Akkadian to Old Babylonian periods. Steinkeller (2007), in an important review of Shimashki’s rulers, places the kingdom in the highlands of the north-central Zagros. In an earlier study, Henrickson (1984), utilizing evidence of archaeological survey and excavation, reached the same conclusion. Daniel Potts (2008), taking both the archaeological and textual record into consideration, places Shimashki in Central Asia, specifically identifying it as the Oxus Civilization, c.2200–1700 BC (a.k.a. the Bactrian Margiana Archaeological Complex [BMAC]). On the other hand, Steinkeller (forthcoming) identifies the Oxus Civilization as Tukrish, yet another eastern, resource-rich land, famed for its presence of lapis lazuli and gold.

The Oxus Civilization was discovered and prolifically described by Victor Sarianidi (1997, 2003, 2004, 2007, 2010). Its distinctive material culture is found on numerous sites throughout the Iranian Plateau (Amiet 1986) and the Indus Civilization (Possehl 2002). Its large fortified structures, distinctive seals and sealings, rich metallurgical tradition, distinctive pottery, and extensive contacts with an outside world, as well as its unique oases settlements, all attest to its cultural complexity. Indeed, its technological achievements and aesthetic products compare favorably with Mesopotamia. It lacks but one attribute: writing. Steinkeller (forthcoming) identifies the Oxus Civilization with Tukrish, an easternmost land, and one noted for its lapis lazuli and gold. This identification is troubled by the fact that the texts mentioning Tukrish date to between 1900 and 1400 BC, a time in which the Oxus Civilization has all but disappeared.

In the Ur III period, texts speak of twenty separate Shimashkian lands stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian and Zagros ranges. Shimashki, as portrayed in the texts, does not seem to offer an accurate picture of our understanding of the archaeology of the Oxus Civilization (Michalowski 1986: 132):

572

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

The Shimashkians who do not consecrate nugig and lukur priestesses in the place of the gods. Whose population is as numerous as grass, whose seed is widespread, who live in a tent, and knows not the place of gods, who mates just like an animal, and knows not how to make offerings of flour, [Even] the evil namtar demon and the dangerous asag demon do not [dare to] approach him, One who, profaning the name of god, violates taboos.

Certainly, this description casts doubt on Potts’ identification of Shimashki with the Oxus Civilization. Settlements of the Oxus cannot be characterized as tent-dwellers while seals, architectural attributes, and rich burials attest to the presence of divinities and offerings. The final verdict on the geographical locale for both Marhasi and Shimashki remains contested.

The recent and extensive archaeological excavations on numerous sites in Iran and Central Asia have led to specific identifications of geographical regions with named political identities. Whether Central Asia is to be identified as Shimashki as D. Potts would have us believe, or Marhasi as Francfort and Tremblay prefer, or Tukrish as Steinkeller indicates, suggest that either archaeology and texts offer contradictory testimony or the evidence from both is insufficient for precise identification.

Political entities need not be coincident with cultural identity. Steinkeller’s attempt to identify Marhasi as inclusive of such sites as Tepe Yahya, Shahr-i Sokhta, Hissar, Bampur, and even extending to the Oxus Civilization, is simply not supported by the archaeological evidence for cultural diversity. This vast region is represented by a plethora of distinctive archaeological cultures. Playing the “name game,” as seen from the distorted political perspective of Mesopotamian texts, simplifies the complexity of the third millennium cultural mosaic that typifies the Iranian Plateau. On analogy, the European Union (as with Elam) is an ambiguously centralized political entity consisting of numerous distinctive cultures, languages, and religions. So it was on the Iranian Plateau. To identify political entities within specific geographical locales casts a political centrality over a far more complex and autonomous cultural complexity. Additionally, identifying the name of any of the above places has, to date, offered virtually no understanding of the indigenous social, religious, economic, and political structure(s) of the named region. Wherever Shimashki is located we know that its king, Kindattu, conquered Ur and after a twenty-year occupation was expelled from Babylonia.

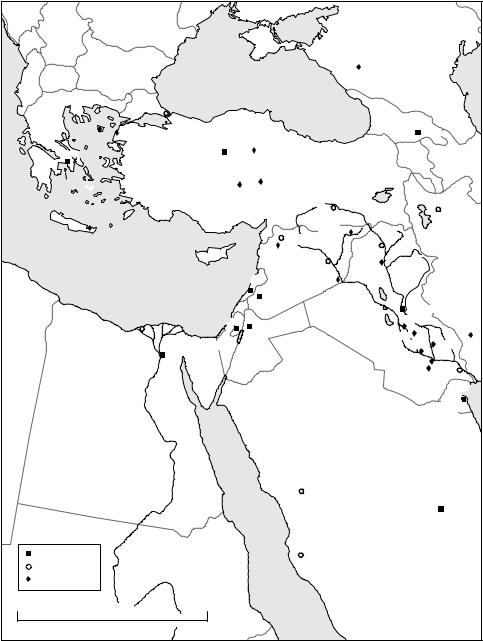

The interaction that characterized each region was, no doubt, different with respect to its nature, structure and specific date. Nevertheless, each region was in contact with others between 2400 and 1800 BC. This period represented an unparalleled degree of cultural exchange and contact. Figure 29.1 does not include Mesopotamia’s interaction with the Eastern Mediterranean, the Levant and Egypt. The figure does, however suggest a series of asymmetric relations. Thus, the Indus Civilization, and the contemporary communities of the Iranian Plateau, are in contact with all of the other regions. Mesopotamian materials are all but absent in the Indus while present in all other regions. The Oxus maintains contact with regions save for Mesopotamia.

Figure 29.1 summarizes the extensive interaction that characterized the late third millennium. Never before, and not again until the rise of the major empires (the Egyptian, Hittite, and Assyrian of the mid-second millennium) was the greater Near East to experience such extensive cultural interaction. The specific “causes” that

573

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RUSSIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maikop |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

Black Sea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

p |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

Istanbul |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

AS |

US |

MTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

R |

|

|

Tbilisi |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Troy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GI |

|

|

|

|

|||||

Poliochni |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Ankara |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Alaca Höyük |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

Athens |

|

TURKEY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M |

|

E |

R |

BA |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

IJAN |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

ANATOLIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Aigina |

Cyclades |

|

Acemhöyük |

Kültepe |

|

|

|

|

|

Lake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Van |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

MTS |

|

R. |

T |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

igris |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tabriz |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

Diyarbakir |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

T |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lake |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tell Brak |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

CRETE |

Mochlos |

|

|

|

|

|

Aleppo |

|

|

Great |

|

|

|

Urmia |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

u |

Mosul |

Zab |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Ebla |

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

leZab |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

CYPRUS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K |

|

|

|

t |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deir ez-Zor |

|

. |

|

Ashur |

it |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

L |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LEBANON |

|

SYRIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Mediterranean Sea |

|

Mari |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

l |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

R. |

Eu |

|

|

|

|

iya |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

Beirut |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ph |

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Damascus |

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

Baghdad |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Jerusalem |

Amman |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kish |

|

|

|

|

|

Susa |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IRAQ |

Nippur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Alexandria |

ISRAEL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uruk |

|

Girsu |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Cairo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

JORDAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SINAI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eridu Basra |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KUWAIT |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kuwait |

|||

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGYPT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medina |

|

|

|

|

SAUDI ARABIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Riyadh |

||

|

|

|

|

Red |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modern capital |

|

|

Sea |

|

Mecca |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Modern city |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ancient site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

Kilometres |

1000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Figure 29.1 Late third millennium interaction spheres

(courtesy of Hélène David, CNRS. Adopted with permission and alterations)

574

–– Iran and its neighbors ––

brought about this late third millennium interaction remain elusive. However, the texts, supported by the archaeological record indicate that powerful centers of cultural cohesion from Mesopotamia to the Indus and from Central Asia to the Arabian Peninsula were characterized by economic and political alliances, gift exchange, and even market economies. The collapse of this pioneering interregional interaction brought prosperity, and what can be called the first classical age, to an end.

In discussing the enduring merits of “classicism,” Glen Bowersock (2010: 135) observes, “if Plato and Cicero must stand alongside Confucius, Ammonites and Ibn Khaldun that has to be judged an enhancement of us all.” As with individuals, so with cultures and nations. When Mesopotamia, so used to its exceptional treatment, is positioned alongside its interacting neighbors–Anatolia, the Caucasus, the Arabian Peninsula, the Iranian Plateau, Central Asia and the Indus Civilization–it too offers an enhancement to our understanding of the significance of remote antiquity.

REFERENCES

Adams, Robert McC. 1962 Agriculture and Urban Life in Early Southwestern Iran. Science, 136:

109–122.

Algaze, Guillermo 2005 The Uruk System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization (second edition). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Alizadeh, Abbas 2006 Origins of State Organizations in Highland Iran: The Evidence from Tall-e Bakun A. Chicago: Oriental Institute.

—— 2010 The Rise of the Highland Elamite State in Southwestern Iran. Current Anthropology, 51

(3): 353–379.

Amiet, Pierre 1986 L’age des échanges inter-iraniens. 3500–1700 avant J.-C. Paris: Editions de RMN. —— 1993 The Period of Irano-Mesopotamian Contacts 3500 B.C-1600 B.C. In Early Mesopotamia

and Iran, ed. John Curtis, pp. 23–30. London: British Museum.

Amiran, Ruth 1988 Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Barth, Frederik 1969 Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. Boston: Little Brown.

Benseval, Roland 1997 Entre le Sud-Est iranien et la plaine de l’Indus: Le Kech-Makran- Recherches archéologiques sur le peuplement ancien d’une marche des confines indo-iraniens. Arts Asiatiques

52: 5–35.

Berman, Judith 1994 The Ceramic Evidence for Sociopolitical Organization in “Ubaid Southwestern Iran.” In Chiefdoms and Early States in the Near East: The Organizational Dynamics of Complexity, ed. G.J. Stein and M.S. Rothman, pp. 22–33. Monographs in World Archaeology 18. Madison: Prehistory Press.

Bowersock, Glen 2010 Mosaics as History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Canal, Denis 1978 La Terrase haute de l’Acropole de Susa. Délégations Archéologique Française en Iran, 1–57. Paris: Association Paléorient.

Carter, Robert and Harriet Crawford 2010 Maritime Interaction in the Arabian Neolithic. Leiden/ Boston: Brill.

Carter, Robert and Graham Philip 2010 Beyond the Ubaid; Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. Chicago: Oriental Institute.

Cohen, Sol 2000 Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D. Ann Arbor Michigan Microfilms.

Collins, Paul 2000 The Uruk Phenomenon: The Role of Social Ideology in the Expansion of the Uruk Culture during the Fourth Millennium BC British Archaeological Reports International Series 900. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Crawford, H.E.W. 1973 Mesopotamia’s Invisible Exports in the Third Millennium. World Archaeology 5: 232–241.

575

–– C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky ––

Dahl, Jacob L. 2009 Early Writing in Iran: A Reappraisal. Iran, XLVII: 23–31.

Damerow, Peter and Robert K. Englund 1989 The Proto-Elamite Texts from Tepe Yahya. The American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 39. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Francfort, Henri-Paul and Xavier Tremblay 2010 Marhasi et la Civilisation de lOxus. Iranica Antiqua, XLV: 51223.

Gibson, McGuire and Muhammed Maktash 2000 Tell Hamoukar; Early City in Northeastern Syria.

Antiquity 74: 477–478.

Henrickson, Robert C. 1984 Simashki and Central Western Iran: The Archaeological Evidence.

Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 74 (1): 98–122.

Hole, Frank 2004 Campsites of the Seasonally Mobile. In From Handaxe to Khan: Essay Presented to Peder Mortensen on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, ed. K. von Folsach, H. Thrane and K. Frifelt,

pp. 67–85. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

——2010 A Monumental Failure; The Collapse of Susa. In Beyond the Ubaid Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Near East, ed. Robert A. Carter and Graham Philip, pp. 227–244. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 63. Chicago: Oriental Institute.

Jacobsen, T. 1939 The Sumerian King List. Assyriological Studies 11. Chicago: Oriental Institute. Johnson, Gregory A. 1973 Local Exchange and Early State Development in Southwestern Iran.

Anthropological Papers 51. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Kardulias, Nick P. 1999 World Systems Theory in Practice. London: Rowman and Littlefield. Kardulias, Nick 2002 Rethinking World Systems. American Journal of Archaeology 105 (44): 719–721. Kohl, Philip L. 1973 The Balance of Trade in Southwestern Asia in the mid-Third Millennium.

Current Anthropology 19: 463–492.

—— 2005 The Making of Bronze Age Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C. 1978 The Proto-Elamites on the Iranian Plateau. Antiquity LII, 205:

114–120.

——1981 Afterword. The Bronze Age Civilization of Central Asia, ed. Philip Kphl. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe.

——1988 The Intercultural Style Carved Vessels. Iranica Antiqua XXIII/I: 45–97.

——1996 The Archaeological Evidence for International Commerce; Public and/or Private Enterprise in Mesopotamia. In Privatization in the Ancient Near East and Classical World, ed. Michael Hudson and Baruch A. Levine, pp. 73–108. Peabody Museum Bulletin 5. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Layard, Henry 1887 Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana and Babylonia. New York: Longman, Green and Co.

LeBrun, Alain 1978 Le Niveau 17B de l’Acropole de Suse (campagne de Délegation Archéologique Française en Iran. Paris: Association Paléorient, 9: 57–155.

Liverani, Mario 2004 Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

—— 2006 Uruk: The First City.London: Equinox.

Lyonnet, B. 2007 Les Cultures de Caucasus Vie-IIIe millénnaires avant notre ère leurs relations avec le Proche Orient. Paris: CNRS.

Madjidzadeh, Yosef 2001 Jiroft. The Earliest Oriental Civilization. Teheran: Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

Madjidzadeh, Y. and H. Pittman 2008 Excavations at Konar Sandal in the Region of the Jiroft in the Halil Basin: First Preliminary Report (2002–2008). Iran XLVI: 70–103.

Masry, A.H. 1997 Prehistory in Northeastern Arabia. The Problem of Interregional Interaction. London: Kegan Paul International.

Michalowski, Piotr 1986 Mental Maps and Ideology: Reflections on Subartu. In The Origins of Cities in Dry Farming Syria and Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium, ed. Harvey Weiss. Guilford, CN: Four Quarters Publishing.

576

––Iran and its neighbors ––

——1995 Sumerian Literary Traditions: An Overview. In Civilization of the Ancient Near East, ed. Jack Sasoon. New York: Scribners.

——2008 Observations on “Elamites” and “Elam” in Ur III Times. In On the Third Dynasty of Ur, ed. Piotr Michalowski. The Journal of Cuneiform Studies Supplemental Series, Vol. 1, pp. 109–124. Boston: American School of Oriental Research.

Michalowski, Piotr 2008 On the Third Millennium of Ur. Boston: American School of Oriental Research.

Mortensen, Peter 1974 A Survey of Prehistoric Settlements in Northern Luristan. Acta Archaelogica

45: 1–47.

Muscarella, Oscar 1973 The Date of the Tumuli at Sè Girdan. Iran 11: 178–180.

Nokandeh, Jebrael 2010 Neue Unteruchingen zur Sialk III Periode im Zentraliranischen Hochland. dissertation.de/buch.php3?buch-6112.

Oates, David and Joan Oates 1976 The Rise of Civilization. London: Elsevier Phaidon.

Oates, Joan 2002 Tell Brak: The Fourth Millennium Sequence and its Implications. In Artifacts of Complexity; Tracking the Uruk in the Near East, ed. Nicholas Postgate, pp. 111–22. Iraq Archaeological Reports 5. Warminster: British School of Archaeology in Iraq.

Palumbi, G. 2008 The Red and the Black, Social and Cultural Interaction Between the Upper Euphrates and Souhern Caucasus Communities in the Fourth and Third Millennium. Roma: Sapienza Universitá di Roma Dipartmento di Scienze Storiche Archeologiche dell’ Antichitá.

Pettinato, G. 1972 Il Commercio con l’Estero della Mesopotamia Meridionale nel 3 Milenio av. Cr. Alla Luce della Fonti Letterarie e Lessicali Sumeriche. Mesopotamia 7, pp. 43–166. Rome.

Possehl, Gregory 2002 The Indus Civilization A Contemporary Perspective. New York: Altamira Press/Rowman and Littlefield.

Potts, Daniel T. 1999 The Archaeology of Elam Fornation and Transformation of an Iranian State.

Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

——2000 Bevel-rim Bowls and Bakeries: Evidence and Explanations from Iran and the IndoIranian Borderlands. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 61: 24.

——2002 Total Prestaton in Ur-Marhasi Relations. Iranica Antiqua XXXVII: 343–358.