- •Introduction

- •1 Physical geography

- •5 The Sumerian language

- •6 History and chronology

- •15 Calendars and counting

- •17 Everyday life in Sumer

- •19 A note on Sumerian fashion

- •21 Death and burial

- •22 Sumerian mythology

- •23 Trade in the Sumerian World

- •26 Sumer, Akkad, Ebla and Anatolia

- •27 The Kingdom of Mari

- •29 Iran and its neighbors

- •30 The Sumerians and the Gulf

- •32 Egypt and Mesopotamia

- •POSTSCRIPT

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

EGYPT AND MESOPOTAMIA

Alice Stevenson

INTRODUCTION

On 2 June 1923 the London Illustrated News published an article entitled ‘The most important historical relic ever found in Egypt’ detailing a lecture in which Flinders Petrie described a recent purchase by the Louvre. The photograph central to the piece was of a carved ivory handle, bearing distinctly Mesopotamian imagery, into which was set a quintessential Egyptian Predynastic ripple-flaked knife: the Gebel elArak knife. For Petrie, the find had re-opened the ‘whole question of the relations of early civilisation in Egypt’ (Petrie 1917: 26). He viewed it as proof that Sumer and Susa were the originating area for his ‘Dynastic race’, who he believed had invaded Egypt at the end of the prehistoric period and instigated Dynastic civilisation. Although his theory continued to be advanced for many years by some (e.g. Emery 1961: 39–40) more sophisticated accounts of the manner in which Mesopotamian elements were incorporated into the early Egyptian world were being formulated. Henri Frankfort (1924, 1941, 1951) rejected Petrie’s model and was the first to synthesise comprehensively

the evidence for the impact of these supposed Eastern imports:

Egypt, in a period of intensified creativity, became acquainted with achievements in Mesopotamia; that it was stimulated; and that it adapted to its own development such elements as seemed compatible with its efforts. It mostly transformed what it borrowed and after a time rejected even these modifications.

(1951: 110)

His eloquent characterisation of the role of Mesopotamian cultural elements in Egypt of the late fourth and early third millennium BC (Frankfort 1951: 110) remains today, some sixty years later, succinctly accurate.

Egypt has long been compared to Mesopotamia (e.g. Trigger 1993; Baines and Yoffee 1998). As Frankfort noted, however, for the study of the development of Egyptian society from the mid-fourth to early third millennium BC Uruk period, Sumer is more than a convenient comparative case study; it was a source and a mediator of some exotic goods and imagery that influenced the indigenous formation of elite cultures in Egypt, as the Gebel el-Arak knife materialises. Nevertheless, in the Egyptian first dynasty of the early third millennium BC, Mesopotamian influences disappear from the archaeological record completely. This marks the end of centuries of selective and

620

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

opportunistic borrowings that include raw materials such as lapis lazuli, a handful of cylinder seals, artistic inspiration from a limited number of glyptic motifs, a few tenuous pottery parallels and, more controversially, the concept of niched architecture. In contrast, no material correlates of reciprocal borrowings from Egypt are currently known from Mesopotamia.

The source, scale and nature of such borrowings in early Egypt has been continually scrutinised since the beginning of the twentieth century. Frankfort’s ideas were enthusiastically taken up by Kantor (1942, 1952), Baumgartel (1955) and Ward (1964) who all drew attention to further artefacts of possible Mesopotamian derivation. The latter part of the twentieth century saw further syntheses by scholars such as Moorey (1987, 1990) and Smith (1992). The validity of specific identifications of some of the imports they describe has been debated persistently as reflected by a vast literature of opinion. It is not the intention here to provide another exhaustive review of the same set of data. Rather the concern is how Egypt became ‘acquainted with achievements in Mesopotamia’ and why certain elements were borrowed in the way they were. To this end, the possible networks of communities through which material could travel should be considered, as there is a tendency to simply juxtapose two ‘great civilisations’ at the expense of appreciating the role of surrounding societies. The analysis of networks through which material flowed from the East to Egypt has in the last few decades focused on the ‘Uruk expansion’ and connections through Syria. This does not, however, preclude the possibility of additional points of entry for exotica and ongoing consideration ought to be given to the wider field of social networks extending across and around the Arabian peninsula. Such an attempt remains complicated by outstanding problems of chronological synchronisation and gaps in the archaeological evidence, but it is still possible to challenge definitive statements about the movement of ideas and materials in prehistory. A second theme explored below concerns how foreign imports may have been socially evaluated through consideration of the reception and incorporation of exotic materials and images. Overall, this review is not intended to be conclusive as many questions remain concerning the dating, materials and routes of exchange, and this field is always open to new findings and interpretations.

PREDYNASTIC AND EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT

In the winter of late 1894 and early 1895, the pioneering archaeologist Flinders Petrie excavated a vast cemetery in Upper Egypt at Naqada. Some 3,000 graves were opened over the course of the season and Petrie was struck by the seemingly ‘wholly unEgyptian’ (Petrie and Quibell 1896: 8) character of the burial assemblages found within. At that time prehistoric Egypt was only a vague concept without tangible reference points and Petrie did not at first recognise that what he had documented at Naqada were in fact the forebears for the better-known dynastic culture. Following similar discoveries, however, the true significance of Naqada as a prehistoric necropolis was accepted. Petrie’s innovative sequence dating of the grave assemblages from both Naqada and cemeteries around Diospolis Parva formed the material framework for what became known as the Predynastic period (Table 32.1).

In stark contrast to Uruk period evidence, mortuary contexts have remained the primary source of data for the interpretation of the Egyptian Predynastic, especially

621

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Table 32.1 Absolute and relative dates compared (adapted from Hendrickx 2006: tab. II.1.7; but cf. Joffe 2000: fig. 1)

Hendrickx period |

Description |

cal. BC |

|

|

|

Naqada IIIC1–IIID |

First–Second Dynasty/Early Dynastic Period |

c.3150/3100–2686 |

Naqada IIIA1–IIIB |

Late Predynastic |

c.3350–3150 |

Naqada IIC–IID2 |

Middle Predynastic (Gerzean) |

c.3600–3350 |

Naqada IA–IIB |

Early Predynastic (Amratian) |

c.4000/3900–3600 |

|

|

|

from the southern part of the country, Upper Egypt. These contexts attest to increasing inequalities in society as the millennium progressed and the establishment of regional elites at the Upper Egyptian centres of Naqada, Hierakonpolis and Abydos (Kemp 2006: fig. 22). More recent work has redressed the bias towards examination of simply the funerary arena. Ongoing excavations at sites such as Hierakonpolis have disclosed a wider picture of social complexity based upon settlement, cemetery, ceremonial and industrial spaces of activity (e.g. Friedman 2004: 2). Publications over the last thirty years have also extended the scope of analysis to include more data from the northern Delta region. This includes the identification of communities living in Lower Egypt around Maadi and Buto in the early–mid Predynastic that were distinct from their Upper Egyptian neighbours in both social practices and material culture (Rizkana and Seeher 1987, 1989). By the end of the fourth millennium BC, Egypt was seemingly unified politically, with those individuals interred in the main burial chambers in the Umm el-Qa’ab at Abydos being recognised as the embodiment of divine kingship, whose role in maintaining order over chaos was paramount.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

Although some form of political unity is understood to have been in place in Egypt by the first dynasty, the process of social and cultural integration had been underway for centuries and the Naqada IIC period in particular was pivotal. In this phase, social practices and material culture associated with Upper Egypt – the so-called ‘Naqadan culture’ – began to appear in Lower Egypt as economic and social centralisation gathered pace. Not only do Upper Egyptian burial traditions become rooted in the Fayum region at this same time, but also an increasing presence of Egyptian goods is noted along the southern coastal plain of the Levant as the introduction of the donkey as pack-horse transformed overland exchange (Wengrow 2006: 39). The spread of material out of Upper Egypt from Naqada IIC is also apparent to the south in Lower Nubia amongst the burials of the ‘A-group’ communities. These groups had been interring their dead in this area since at least Naqada IC, but in Naqada IIC the presence of Upper Egyptian material becomes marked.

The material associated with this Naqada IIC expansion is distinctive and as such it forms a clear relative dating horizon. For instance, a new type of harder pottery fabric, marl clay, was introduced in Naqada IIC. Within this medium forms inspired by foreign material culture appear, such as wavy handles (Petrie’s W-ware) borrowed from Levantine imports. Such objects thus materialised the expanding interaction

622

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

spheres of the Nile’s inhabitants who incorporated outside influences within their own technologies. However, despite the horizon’s distinctiveness in relative terms, its absolute resolution oscillates over a 200-year time range. High chronologies favour a date c.3600 BC for the beginning of the Naqada IIC phase (e.g. Hendricx 2006), while lower estimates place its onset at c.3400 BC (e.g. Joffe 2000). The restricted number of currently available radiocarbon dates does not permit greater resolution, but new datasets may in future clarify some issues (cf. Bronk et al. 2010). Whether full synchronisation is truly possible remains to be seen, however, as temporal signatures in separate regions are based on different contexts and taphonomic environments.

In comparison, the Mesopotamian temporal framework has been refined over the last ten years, providing a longer duration for the Uruk expansion (Joffe 2000; Schwartz 2001; Wright and Rupley 2001). In place of a short-lived phenomenon restricted to the Late Uruk period, an extension of Uruk material into Syria is recognised in LC4, dated roughly to 3600–3400 BC, which still corresponds approximately with the Naqada IIC phase. These new estimates accommodate the evidence for Mesopotamian influences in Egypt far better than had ever previously been the case (Joffe 2000). This is particularly so with regard to the occurrence of lapis lazuli, cylinder seals, glyptic motifs and (perhaps) niched architecture.

LAPIS LAZULI

The overlap of social networks radiating out from both Egypt and Mesopotamia is first signalled in the Egyptian archaeological record by the striking semi-precious stone lapis lazuli. This vibrant blue and speckled pyrite material is one of the most direct pieces of evidence archaeologists have for the links extending from the East to Egypt, for it is unknown in Egypt itself, as are the geological conditions necessary for its formation (Bavay 1997: 80). The most likely provenance is in the Badkhshan province of Afghanistan, although an alternate source in the Chagai Hills of Pakistan (Casanova 1992) remains unsubstantiated for this time period. An estimated 167 Egyptian Predynastic graves out of some 15,000 known contained lapis (Hendrickx and Bavay 2002: tab. 3.3), but given the statistical vagaries introduced by tomb robbing and the limitations of early excavation reports, this occurrence is likely to have been higher. Nevertheless, the amount of lapis in circulation was still limited and contact with the East is likely to have only been small scale and indirect.

Lapis first appears sporadically in one or two graves in Naqada I/II, but it is not until Naqada IIC that a definite presence of lapis across Upper Egyptian communities is established (Hendrickx and Bavay 2002: tab. 3.3). It has been found in a cross-section of Upper Egyptian burial contexts, from small, basically furnished burials to large tombs with more elaborate assemblages. By the first dynasty, however, lapis appears to be restricted to only the most elite of contexts, including the burials of the first rulers. Yet in the succeeding second and third dynasties not a single example can be cited and some lapis found in the tomb of King Qa’a, the final king of the Egyptian first dynasty (Hendrickx and Bavay 2002: 66), is the last known example for almost half a millennium. It is not until the fourth dynasty that it appears again, notably in the burial of Queen Hetepheres, a wife of King Sneferu (c.2613–2589 BC). Whether this is a true hiatus in lapis availability is uncertain, as second dynasty contexts are very poorly attested relative to the previous dynasty.

623

–– Alice Stevenson ––

As it stands, however, this parabolic pattern of lapis lazuli occurrence over time does coincide with the ebb and flow of social networks across the Egyptian and Sumerian worlds. For instance, one of the earliest cemeteries in Lower Egypt associated with the northwards spread of Naqadan social practices is el-Gerzeh, founded in Naqada IIC and which notably has a high concentration of lapis (Stevenson 2009: 118–119). Out of 298 graves, sixteen were found to contain lapis, the highest percentage of graves with lapis known from any Predynastic cemetery of that date. The high incidence of lapis at el-Gerzeh relative to other cemeteries may be attributable to the unusually intact condition in which the majority of tombs were found. It might also, however, point to the social ability of community members here to acquire material through the new opportunities afforded by closer proximity to the expanding social currents in Mesopotamia.

Passage through the Uruk colonies in Syria and then across a sea route from the northern Levant is currently the favoured model (Kantor 1992; Moorey 1987, 1990; Tessier 1987) and certainly the discovery of lumps of raw lapis at Jebel Aruda (van Driel and van Driel-Murray 1979: 19–20) is suggestive of such a route. The role of Byblos on the Levantine coast has been noted in this context as a possible intermediary between the Uruk and the Egyptian worlds (Prag 1986). This, however, is disputed (e.g. Philip 2002: 219) and not until the first half of the third millennium BC does the port definitely occupy a central position in inter-regional trade. This in itself is part of a wider pattern of shifting exchange interests and opportunities. Just as the upturn in the quantity of lapis coming into Egypt coincides with a meeting of the Uruk and Naqada expansions, its seeming disappearance at the end of the first dynasty corresponds with the retraction of the Uruk sphere of influence.

The coincidence of lapis in both Egypt and Syria, however, does not necessarily prove a direct or exclusive ‘trade’ route (contra Marks 1997). As a visually striking substance, lapis invited complex biographies as it circulated through communities and travelled far from its geological point of origin. At el-Gerzeh, as at most Predynastic sites, lapis is most usually found in the form of small disc beads that comprise part of longer composite strings of beadwork. Such beads are frequently so tiny and so few in number that they were not visually prominent in the wider set. In such small quantities, lapis could have been transported the 4000 km to Egypt by any number of routes, through multiple hands and via several stops (Sherratt and Sherratt 1991: 357). Thus while lapis was likely propelled north through Sumer, it could also have become entangled in other geographies of exchange bypassing Sumer entirely. For instance, it has been noted (Smith 1992: 245) that the earliest parallels for glyptic art found in Egypt (see below) are with Susa, rather than Sumer suggesting that the former could have been the southern Mesopotamian intermediary for the transmission of imports, such as lapis, to the Nile Valley.

A sea route around or a land route across Arabia, for instance, has long been mooted. In the earlier twentieth century, this was considered to be the direct link between Egypt and Mesopotamia (e.g. Frankfort 1951: 110–111; Kantor 1952: 250; Petrie 1917), with the Wadi Hammamat in Egypt’s Eastern desert seen as providing the crucial channel connecting the Nile to the Red Sea. Early rock art depicting high-prowed boats was cited as evidence to support this maritime connection (Winkler 1938: 26), as were the boats carved on the Gebel el-Arak handle (Petrie 1917). Yet as Moorey noted (1987: 39) Winkler’s boat distinctions are not clear cut and their distribution is not restricted to

624

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

the Wadi Hammamat, as they are also found some 130 km south of the First Cataract. As for the Gebel el-Arak handle, Moorey has drawn attention to the Egyptian attire of the so-called invaders, casting doubt on ‘whether the ships with rising prows and sterns have anything to do with Mesopotamia,’ (Moorey 1987: 39).

Notwithstanding these issues, sea contact cannot be categorically ruled out. The Arabian peninsula occupies a central juncture between the Indian subcontinent and Africa and is noted as witnessing some of the earliest known maritime trade activities and seafaring routes (Boivin et al. 2009). It is only in the last decade or so that details from new archaeological work in countries such as Oman have been forthcoming, providing new evidence that communities in this part of the world were embedded within a wider nexus of exchange relations encompassing the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia, often mediated in the early second millennium by Dilmun. Similarly, the extent of Indus valley activities has also begun to be revealed (Agrawal et al. 2010) and lapis bead working is noted in the earliest levels at Harappa, c.3300–2800 BC (Kenoyer 1997: 267). These activities largely post-date the introduction of lapis into Egypt and most of the reported evidence concerns the later third and early second millennium BC. Nevertheless, this evidence highlights how a range of societies made up possible chains of connections and it is clear that future investigations have the potential to alter our understanding of the dynamics of exchange across this region in earlier periods. Communities in Egypt at least seem to have tapped into networks on the side of the Red Sea early on as evidenced by the presence of obsidian in several Predynastic graves (Hendrickx and Bavay 2002). Recent studies of obsidian artefacts suggest that several had an origin either in the hinterland of western Yemen on the Arabian peninsula, or from a region on the Eritrean coast and the northern part of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia (Aston et al. 2000: 46; Bavay et al. 2000; Zarins 1989: 367). Other studies indicate that Anatolian sources were also being exploited, and unworked obsidian has been found on the Lebanese coast suggesting a northern maritime route (e.g. Bavay et al. 2000). Obsidian thus demonstrates the multiple pathways of exchange around Egypt at this time. Although international connections for lapis are attested from the mid-third millennium BC at places such as Tarut, an island in the Gulf close to the Arabian coast (e.g. Aruz 2003: 324), lapis is currently not attested in the archaeological record of the Arabian peninsula for the fourth or early third millennium BC. It thus remains, for the time being, an unproven possible avenue of early exchange between Egypt and the East.

The lack of inter-regional evidence may in itself turn out to be significant. For example, the disparity between the conspicuous impact of Mesopotamian imports on communities in the Nile valley at the end of the fourth millennium BC and the minimal evidence for an equivalent influence on the Levant is notable. Philip (2002: 225) suggests that this may be attributed to the social contexts of reception whereby, despite widespread contacts, only certain communities with favourable social or political circumstances accommodated foreign elements within their own traditional practices. In this regard, the timing of Uruk expansion was fortuitous and rather than instigating developments in Egypt, communities of the Nile Valley seem to have been particularly receptive to exotic resources that could be creatively incorporated into already developing cosmologies (see below). Moreover, Egypt had particular contexts of consumption in the form of display-orientated burial practices which have been more favourable to the preservation of material culture than is the case elsewhere.

625

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Regardless of its route, at lapis’ final point of consumption in the funerals of Predynastic Egyptians, its actual source was probably not known to the mourners. It would, however, have been recognised as non-Egyptian and exotic from its vibrant, unusual appearance and for that very reason it was a substance of significance and, potentially, a source of social power. As Helms (1988) has argued, long-distance interests for ‘prestige goods’ are not merely trade pathways, as geographical distance is a symbolic construction invested with power. Exotica, she contends, involve intangible knowledge of distant landscapes regaled in shared oral narratives that are made manifest by the materials from those places. Power may be acquired by access to imported goods and those individuals or groups who obtain such items may lay claim to the esoteric, specialist knowledge that such things imply. It is not merely the peculiar nature of such knowledge that is significant, but also the politics that are involved in accessing such information. In this manner, material from the Sumerian World could serve as potent resources for those attempting to negotiate their own social environments.

CYLINDER SEALS

One Predynastic Egyptian burial in which lapis beads were placed was T29 at Naqada, the site first excavated by Petrie in 1894. The burial is one of the more unusual Predynastic tombs in that it appears to have been a large, communal interment, as were many in Naqada Cemetery T. This necropolis was also separated spatially from the main cemetery where single inhumations were the norm. What is particularly notable about the burial assemblage is that it also contained a cylinder seal, a hallmark of ancient Near Eastern cultures. The seal’s geometric design is made up of three ovals enclosed in irregular borders, which can be compared with examples known from Telloh and Susa. The co-occurrence of lapis and cylinder seal in this grave is perhaps suggestive of a common transmission route. A second example was discovered in the main cemetery, in grave 1863, and is now in the Petrie Museum, London (UC5374). The piece, carved in brown limestone, is incised with curved lines including what may be the representation of fish swimming in water, similar to designs from Ur, Tell Brak and Tepe Gawra. These pieces are two of only approximately twenty known cylinder seals in Egypt (Boehmer 1974a; Podzorski 1988) although, unlike the Naqada examples, some might be local imitations. Neither context at Naqada allows for a precise date as diagnostic pottery is absent from both, but they can be placed broadly in mid to late Naqada II. Notably, many of the earliest cylinder seals formed part of composite bead sets and may thus have been valued in the context of personal display, in a similar way to lapis, rather than indicative of administrative activities (Podzorksi 1988; Wengrow

2006: 187).

In addition to cylinder seals, at least one if not two stamp seals are also known: one from Naga-ed-Der from an otherwise unremarkable tomb (Podzorski 1988), the other possibility being a red jasper example from Harageh (Engelbach and Gunn 1923). In the context of transmission routes, it is perhaps significant that the latter is a site close to Gerzeh in Lower Egypt and the seal is said to be Syrian in origin (Moorey 1990: 63). While stamp seals do not seem to have inspired the production of local imitations, cylinder seals were quickly adopted. Moreover, recent discoveries in six Naqada IID graves in Abydos Cemetery U demonstrate that the practice of sealing was known by

626

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

then (Hartung 1998; Hill 2004). These sealings were all made in local Nile mud and incorporated distinctively Egyptian imagery. Thus, like the wavy-handled pottery, an import was quickly appropriated to convey manifestly Egyptian concepts.

MOTIFS

Such foreign cylinder seals may have been the medium for the transmission of Near Eastern glyptic art (Amiet 1980), another category of import that has long been recognised. However, the imported examples in Egypt, like those at Naqada, all carry schematic rather than figurative designs. It is possible, however, that figural seals were also introduced into Egypt as even in Mesopotamia there are few protoliterate figural seals known outside of Uruk (Pittman 1996: 16). It is also conceivable that seal impressions themselves may have made it to Egypt.

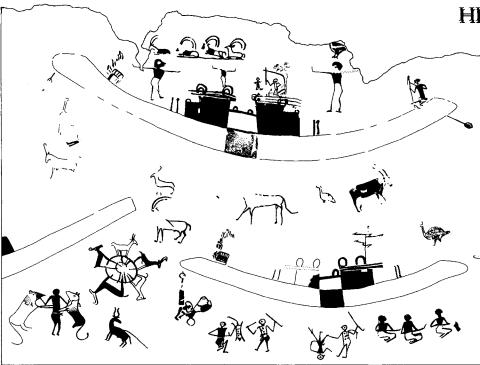

The range of motifs adopted was selective and only a handful are recognised including: felines with long necks, the winged griffin, the master of beasts, snakes twisted around rosettes and animals in procession and in human attitudes. They were not incorporated into an Egyptian glyptic, but translated into relief carvings on characteristically Egyptian ceremonial objects such as knife handles, like the Gebel elArak knife, and palettes of the latter part of the fourth millennium (Asselberghs 1961: pls. 43–52, 122–23, 127–28, 151, 168–169; Boehmer 1974b). Just a single motif has been found fixed in its original context, painted on the wall of the only known decorated tomb from the entire Predynastic period. Dated to Naqada IIC, Hierakonpolis tomb 100 is one of the largest known burials of the era (Kemp 1973; Quibell and Green 1902). Across the white mud-plastered background of the subterranean chamber were images of animals, boats and humans in combat. In the midst of this scene is a motif more familiar from round button seals and impressions from Susa than anything in the Egyptian repertoire; that of the hero/ruler as master of animals (Amiet 1980; Smith 1992). At Hierakonpolis the figure holds back two opposing feline creatures (Figure 32.1), perhaps lions, and it represents the earliest borrowed design in Egyptian art. It is certainly lions that are featured on the Gebel el-Arak knife handle. So striking is this image that it has been suggested that it forms evidence for the presence of Mesopotamian craftsmen in Egypt (Sievertsen 1992: 58; Trigger 1993: 39–40). Yet given the occurrence of lapis and cylinder seals in Egypt, it is clear that objects were entangled within wider currents of material circulation that could easily have brought images to Egypt, not necessarily itinerant craftsmen.

Such knives tend to date to Naqada IIC/IID, but as luxury artefacts they may have been in circulation for generations before being reworked to accommodate decorated handles. Most known examples have appeared on the art market without provenance, leaving assessments reliant upon art historical parallels that generally placed the carvings in Naqada III. Recent finds of seven similar ivory handles in the elite cemetery U at Abydos, however, have provided Naqada IID contexts (Dreyer 1999). Glyptic images are less apparent on the ceremonial palettes. Plain siltstone palettes were relatively common throughout the Predynastic and were used as a surface on which to grind cosmetic pigments. Towards the end of the fourth millennium BC these were appropriated by the elite as a vehicle for conveying the ideology of kingship and incorporated some foreign elements to this end. The most prominent example, two felines with long entwined necks, appears on the famous Narmer palette.

627

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Figure 32.1 Portion of the painted wall of Naqada IIC tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis. A figure holding back two animals can be seen in the bottom left-hand corner, a motif seen first on round button seals from Susa, but later also common in the

Sumerian glyphic repertoire (Kemp 2006: 80)

The similarity of many of these images to Susan as opposed to Sumerian styles has been noted (e.g. Boehmer 1974a: 514; Moorey 1987: 39; Smith 1992: 245), but perhaps overstated as evidence of a transmission route that bypassed Sumer. Given that these iconographical features have been found in Northern Syria on the LC4–5 sites of Habuba Kabira, Sheikh Hassan and Jebel Aruda (Pittman 2001), it is not necessary to seek their direct origin as far as Susa. Ultimately, however, it is possible that seals and sealings were conveyed along several routes.

As other scholars have noted (e.g. Moorey 1987), the original meanings associated with these motifs within the Sumerian world may not have been known in Egypt and indeed could have been irrelevant as they were reinterpreted to fit the developing ideology of the Egyptian elite. Moorey suggested (1987: 43) that they were symbols of the authority and power of the distant people who controlled access to such exotic materials as lapis. Yet as with lapis, the potency of these images was as much bound up with their status simply as exotic imports and their inherent drama as in whatever they may have symbolised. Their fantastical nature lent them a unique position outside the indigenous repertoire of representation, which by contrast drew from the Egyptian’s natural environment (Pittman 1996: 19–22). Consequently, such images were appropriate references for the margins of the Egyptian’s known world. They were

628

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

thus easily accommodated within the developing elite’s concern with ‘the containment of unrule’ and the domination of order over chaos (Baines 1995: 13–14; Kemp 2006: 92–99). The potency of these images as representations of the dangerous edges of the habitable landscape may also explain the manner in which they were materially incorporated into the Egyptian world. The positioning of such images on the handles of knives, for example, made it possible for certain individuals to physically grasp them, effectively smothering and controlling these images of chaos. The association of ceremonial object and elite subject in this way, as Baines (1995) has suggested, restricted modes of communication and display to an inner elite and these images did not circulate beyond this enclosed social world.

OTHER EARLY IMPORTS

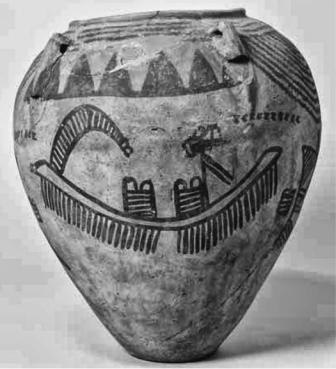

The case for directly imported Mesopotamian pottery is much weaker. Baumgartel (1955: 52–102) argued strongly for extensive Mesopotamian influence upon decorated pottery. Few scholars, however, regard the simple geometric patterns as evidence for the adoption of foreign designs and debate has focused instead on ceramic form. The most convincing parallels are triangular lug handles present on some painted vessels of Naqada IIC/IID (Petrie 1921: pl. XXXIV–V; Figure 32.2). The marl pottery fabric and the designs upon them are local, but the type of handles are known from Uruk pottery (Amiran 1992: 427–428) and form another example of the selective incorporation of foreign elements within the local oeuvre similar to the adoption of the Canaanite wavy handle. Imported prototypes are rare, but a sherd from Badari (Petrie Museum UC9796) and a vessel from Mostegedda (Brunton 1937: pl. 32.3) should be noted. More direct imports in the form of spouted vessels have also been claimed (e.g. Marks 1997; Wilkinson 2002), but the ware of many of these is local (contra Wilkinson 2002) and independent invention or local imitation is possible for this rather generic form (Hendrickx and Bavay 2002: 70). Thirteen sherds found in the Delta at Buto that were identified as Amuq F-ware ceramics from Northern Syria (Köhler 1992, 1998) remain contentious (Faltings 1998: 366–371). On the subject of pottery sherds, it should be noted that only one piece of evidence for Egyptian material in the Sumerian world has been proposed: a fragment of ‘black incised’ pottery (N-ware) found at Habuba KabiraSouth (Sürenhagen 1986: 22), a type of ceramic created in Egypt’s neighbouring Nubia. This fragment is, however, small (<5cm) and its identification is open to question.

The material elements so far mentioned are the most visible references in the archaeological record to wider exchanges from beyond Egypt. There remain, however, more ambiguous traces, such as the movement of resins, as these are more difficult materials to analyse. A wide variety of resins may have been exploited by Egyptians and while Levantine sources were more accessible, resources are widely distributed (Serpico 2000). Similarly, bitumen could have been available to Egyptians from a number of locations and deposits in the Near East (Serpico 2000: 454). More intangible still are supposed stimuli for technical concepts such as writing and faience production, for which Mesopotamian origins have been proffered (Dalley 1998: 11; Lucas and Harris 1962: 464–465), but for which no substantiation currently exists (Tite and Shortland 2008: 58). In the case of writing, recent evidence from tomb U-j at Abydos has certainly pushed back the date for the earliest notation in Egypt to Naqada IIIA1, but this is far from establishing whether this or the Mesopotamian system is older (Baines 2004: 176).

629

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Figure 32.2

Decorated pottery vessel from Predynastic Egypt, Naqada II, with triangular lug handles (E10758, courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

BUILT ENVIRONMENT

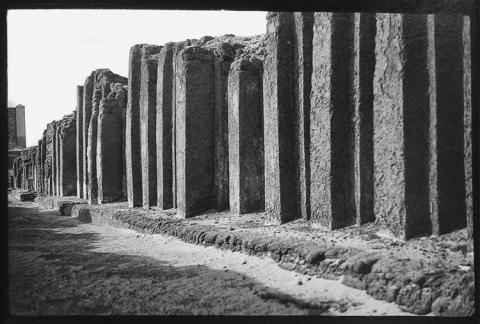

In contrast to the portable ceremonial artefacts that were the restricted preserve of a small inner circle of elites, are the once highly visible and imposing funerary monuments that appear in the first dynasty at sites such as Abydos, Saqqara (Figure 32.3), Naqada, Tarkhan, Naga-ed-Der, Giza and Abu Roash. The external façades of these mud-brick mastaba structures were niched in a manner that recalls Uruk temples. In Egypt, such architecture is often referred to as the ‘palace façade’ as it was long assumed to be connected with the appearance of the royal palace. This hypothesis was seemingly confirmed in the 1970s with the discovery of a monumental Early Dynastic gateway at Hierakonpolis (Fairservis et al. 1971–72: 29–33). The association of the palace façade with kingship was further encoded in the form of the serekh, introduced in the late Predynastic (Naqada III), which by the Early Dynastic period was the convention for framing the royal name.

When Frankfort (1924: 124) first postulated a Near Eastern origin for Egyptian buttress-recessed architecture, the only comparisons then available were from sites such as Ur. Further discoveries at Uruk and Tepe Gawra permitted Frankfort (1941) to further extend his thesis, but it was not until the 1970s and 1980s with the unexpected discovery of buttress-recessed structures at Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda that a wider comparative context was revealed. To many, these discoveries were further testament to the consequences of the ‘Uruk expansion’, and underscored the role of the ‘Syrian connection’ in introducing Uruk forms to Egypt (e.g. Moorey 1987: 40–46, 1990: 62).

630

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

Figure 32.3 First Dynasty niched mastaba at Saqqara (photograph in the Lucy Gura Archive, Egypt Exploration Society, courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society)

Others (e.g. Hendrickx 2001) have remained sceptical, rightly pointing out that the development of Egyptian architectural forms is difficult to substantiate given that early funerary superstructures were constructed in perishable materials, as is evident from the elite necropolis at Hierakonpolis where all that remain are post holes. Hendrickx (2001: 97) also cites differences in building technique between Uruk and Egyptian palace-facade forms.

Corroborative evidence for an external impetus seemed to come in the 1980s when it was reported that terracotta wall pegs of typical Uruk type, yet made in local Nile clay, had been recovered from Buto in the western Delta (von der Way 1987). These apparent architectural embellishments were not, however, found in the context of any structure and their identification as decorative nails has lost support, as has the idea of a Lower Egyptian origin for niched architecture (van den Brink 2001). Material references for contacts with Syria in the Delta archaeological record are thus, at present, threadbare. Circumstantially, it remains the case that the sudden appearance of the niched form in Egypt seems to occur against the backdrop of the much longer developmental sequence in Mesopotamia (Sievertsen 2008) and an external influence remains plausible. Frankfort also advanced the idea that it was not just the style of these buildings, but their very substance, mud-brick, that was introduced from Mesopotamia (see also Sieversten 2008: 791–794). He argued that there was no evidence for extensive use of mud-brick before the Dynastic period although there is now limited evidence for its development, at least from Naqada II (Kemp 2000). Others have proposed a Levantine influence (e.g. Rizkana and Seeher 1989: 49–56).

631

–– Alice Stevenson ––

If not the technology, but the appearance of niched architecture can be attributed to outside inspiration, it might be questioned whether it is necessary to rely on itinerant Near Eastern peoples to explain the construction of such monuments in Egypt (cf. Moorey 1987: 64; Hendrickx 2001: 97; Sievertsen 2008: 800; von der Way 1992: 220). Such a movement of people is admittedly conceivable, but the role of oral transmission of knowledge that accompanied the spread of lapis, seals and possible sealings cannot be discounted. Pictorial prompts to such narratives certainly occurred on Sumerian and Susan sealings, such as a sealing from the Red Temple at Uruk (Amiet 1980: pl. 200; Smith 1992: 238–240), and these might hypothetically have inspired their realisation in the Egyptian landscape, although this remains to be examined critically.

LEGACIES

The break in the evidence for Mesopotamian influence in Egypt is often explained by the apparent collapse of the Uruk expansion. Yet, this cession owes as much to shifts in the Egyptian world as it does the Sumerian. In the first dynasty, the Egyptian state sought to consolidate a bounded national identity through ‘internal colonisation’ (Wengrow 2006: 142–146) and relations were curtailed around a southern and a northern border; the Nubian A-group disappears and following the direct expansion of Egyptian groups into southern coastal Levant in Naqada IIIA–C1 (Levy and van den Brink 2002), the Egyptian presence recedes markedly.

The disappearance of Mesopotamian images from the elite visual repertoire in the first dynasty cannot be explained simply as a constriction in social networks as it was not just the motifs that disappeared: the very medium of their realisation vanished, never to be revived in subsequent dynasties. The ceremonial palettes, mace-heads and ivory knife handles are a distinctly late Predynastic phenomenon. As Wengrow (2006: 216) has suggested, such ceremonial objects confined these images to restricted material forms that impeded their incorporation into the wider social world in which they had little relevance. It would take another florescence in cultural creativity afforded by the fragmentation of the centralised Old Kingdom c.2160 BC for foreign motifs to once again find an available niche.

The ‘palace-façade’ architecture, on the other hand, was a more enduring feature perhaps because, unlike the ceremonial objects, they were so visibly rooted in Egyptian surroundings and thereby normalised. While by 3000 BC such structures had largely disappeared in Mesopotamia, niched façades remained in use for Egyptian tomb architecture until the late Old Kingdom and in the third dynasty was adopted for stone sarcophagi. In these contexts niched architecture was unmistakably Egyptian.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

By the time small lapis beads started to filter into the Nile Valley in the latter half of the fourth millennium BC, Egypt was already on a trajectory of increasing social complexity. Lapis was caught up in these developments as one material amongst many that could be drawn upon as a source of social power. Within centuries it was not just what could be held in the palm, but what could be perceived in the landscape that might represent most eloquently the impact of foreign imports in the Egyptian world. Regardless of whether or not specific cultural attributes were or were not Sumerian in

632

–– Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

origin, it is clear that any such influences were subject to local redefinition, resulting in a distinctly Egyptian material culture. Such conclusions are not new nor are they in dispute. Similarly, we cannot yet discount Frankfort’s (1951) closing observation of his seminal work that ‘the question where contact between Egypt and Sumer took place must remain, for the moment, a matter of surmise’. The question can be reformulated, however, for it presupposes a singular point of intersection. Rather, it is the social networks through which these elements traversed and the local contexts in which they were consumed that remain to be fully qualified, not just within the Egyptian and Sumerian worlds, but also in the spaces in between.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to Lisa Mawdsley and Paul Smeddle for commenting on an earlier draft of this text and to Harriet Crawford for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, D.P., Kharakwal, J.S., Rawat, Y.S., Osada, T and Goyal, P. (2010) ‘Redefining the Harappan hinterland’. Antiquity 84 (323). Online: http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/agrawal323/ (accessed

24/07/2010).

Amiet, P. (1980) La glyptique Mésopotamienne archaique. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Amiran, R. (1992) ‘Petrie’s F-ware’. In E.C.M. van den Brink (ed.) The Nile Delta in Transition:

4th–Third Millennium B.C.. Tel Aviv: Pinkhas.

Aruz, J. (2003) Art of the First Cities. The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus.

New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Asselberghs, H. (1961) Chaos en beheersing: Documenten uit aeneolithisch Egypte. Leiden: Brill. Aston, B., Harrell, J. and Shaw, I. (2000). ‘Stone’. In P. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds) Ancient Egyptian

Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baines, J. (1995) ‘Kingship, definition of culture, and legitimation’. In D. O’Connor and D.P. Silverman (eds) Ancient Egyptian Kingship. New investigations. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

—— (2004) ‘The Earliest Egyptian Writing: development, context, purpose’. In S.D. Houston (ed.)

The First Writing: Script invention as history and process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Baines, J. and Yoffee, N. (1998) ‘Order, legitimacy, and wealth in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia’.

In G.M. Feinman and J. Marcus (eds) Archaic States. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Baumgartel, E. (1955) The Cultures of Prehistoric Egypt. London: Oxford University Press.

Bavay, L . (1997) ‘Matière première et commerce à longue distance: le lapis-lazuli et l’ Égypte prédynastique’. Archéo-Nil 7: 79–100.

Bavay, L., de Putter, T., Adams, B., Navez, J. and Andre, L. (2000) ‘The origin of obsidian in Predynastic and Early Dynastic Upper Egypt’. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 46: 5–20.

Boehmer, R.M. (1974a) ‘Das Rollseiegel im prädynastischen Ägypten’. Ärchaologischer Anzeiger

4: 496–514.

—— (1974b) ‘Orientalische Einflässe auf verzierten Messergriffen aus dem prädynastischen Ägypten’. Archäeologischen Mitteilungen aus Iran 7: 15–40.

Boivin, N., Blench, R. and Fuller, D. (2009) ‘Archaeological, Linguistic and Historical Sources on Ancient Seafaring: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Early Maritime Contact and Exchange in the Arabian Peninsula’. in M. Petraglia. and J.I. Rose (eds) The Evolution of Human populations in Arabia. Netherlands: Springer Academic Publishers.

633

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Bronk Ramsey, C., Dee, M.W., Rowland, J.M., Higham, T.F.G., Harris, S.A. Brock, F., Quiles, A., Wild, E.M., Marcus, E.S. and Shortland, A.J. (2010) ‘Radiocarbon-based chronology for Dynastic Egypt’. Science 328: 1554–1557.

Brunton, G. (1937) Mostagedda and the Tasian Culture. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt.

Casanova M. (1992) ‘The sources of the lapis lazuli found in Iran’. In J. Gerry and R.H. Meadow (eds) South Asian Archaeology, 1989. Papers from the Tenth International Conference of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe. Madison: Prehistory Press.

Dalley, S. (1998) The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dreyer, G. (1999) ‘Motive und Datierung der dekorierten prädynastischen Messergriffe’. In C. Ziegler (ed.) L’Art de l’Ancien Empire égyptien. Paris: Documentation française.

Emery, W.B. (1961) Archaic Egypt. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Engelbach, R. and Gunn, B. (1923) Harageh. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt. Fairservis, W.A., Weeks, K. and Hoffman, M. (1971–72) ‘Preliminary report on the first two seasons

at Hierakonpolis’. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 9: 7–68.

Faltings, D. (1998) ‘Recent excavations at Tell el-Fara’in/Buto: New finds and their chronological implications’. In C.J. Eyre (ed.) Proceedings, 7th International Congress of Egyptologists. Leuven: Peeters.

Frankfort, H. (1924) Studies in Early Pottery of the Near East. Vol. 1: Mesopotamia, Syria, and Egypt and their earliest interrelations. London: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

——(1941) ‘The origin of monumental architecture in Egypt’. American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 63: 329–58.

——(1951) The Birth of Civilization in the Near East. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Friedman, R. (ed.) (2004) Nekhen News 16.

Hartung, U. (1998) ‘Prädynastiche Siegelbrollungen aus dem Friedhof U in Abydos (‘Umm elQa’ab)’. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäeologischen Institus. Abteilung Kairo 54: 187–217.

Helms, M. (1988) Ulysses’ Sail: An Ethnographic Odyssey of Power, Knowledge, and Geographical Distance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hendrickx, S. (2001) ‘Arguments for an Upper Egyptian origin of the palace-façade and the serekh during Late Predynastic–Early Dynastic times’. Göttinger Miszellen 184: 85–110.

——(2006) ‘Predynastic-Early Dynastic chronology’. In E. Hornung, R. Krauss and D. Warburton (eds) Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Hendrickx, S. and Bavay, L. (2002) ‘The relative chronological position of Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic tombs with objects imported from the Near East and the nature of interregional contacts’. In E.C.M. van den Brink and T. Levy (eds) Egypt and the Levant. Interrelations from the 4th through the Early third Millennium B.C.E.. London and New York: Leicester University Press.

Hill, J. (2004) Cylinder Seal Glyptic in Predynastic Egypt and Neighbouring Regions. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Joffe, A.H. (2000) ‘Egypt and Syro-Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium: implications of the New Chronology’. Current Anthropology 41: 113–123.

Kantor, H. (1942) ‘The early relations of Egypt with Asia’. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 1: 174–213.

——(1952) ‘Further evidence for early Mesopotamian relations with Egypt’. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 11: 239–250.

——(1992) ‘The relative chronology of Egypt and its foreign correlations before the Late Bronze Age’. In R.W. Ehrich (ed.) Chronologies in Old World Archaeology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kemp, B. (1973) ‘Photographs of the decorated tomb at Hierakonpolis’. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59: 36–43.

—— (2000) ‘Soil (including mud-brick architecture)’. In P. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds) Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

634

––Egypt and Mesopotamia ––

——(2006) Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (second edition). London: Routledge. Kenoyer, J.M. (1997) ‘Trade and technology of the Indus Valley: new insights from Harappa,

Pakistan’. World Archaeology 29(2): 262–80.

Köhler, C. (1992) ‘The preand early dynastic Pottery of Tell el-Fara’in (Buto)’. In E.C.M. van den Brink (ed.) The Nile Delta in Transition: 4th–third millennium B.C.. Tel Aviv: Pinkhas.

——(1998) Tell el-Fara’in – Buto III, Die Keramik von der späten Naqada-Kultur bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Shichten III bis VI). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Levy, T.E. and Van den Brink, E.C.M. (2002) ‘Interaction models, Egypt and the Levantine periphery’. In E.C.M. van den Brink and T.E Levy (eds) Egypt and the Levant: Interrelations from the 4th through the early third Millennium B.C.E.. London and New York: Leicester University Press.

Lucas, A. and Harris, J.R. (1962) Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (fourth edition). London: Arnold.

Marks, S. (1997) From Egypt to Mesopotamia. A study of Predynastic trade routes. Texas: A&M University Press.

Moorey, P.R.S. (1987) ‘On tracking cultural transfers in prehistory: the case of Egypt and Lower Mesopotamia in the Fourth Millennium B.C.’ In M. Rowlands, M. Larsen and K. Kristiansen (eds) Center and Periphery in the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1990) ‘From Gulf to Delta in the fourth millennium BCE: the Syrian connection’. Eretz-Israel

22: 62–69.

Petrie, W.M.F. (1917) ‘Egypt and Mesopotamia’. Ancient Egypt 1917: 26–36.

—— (1921) Corpus of Prehistoric Pottery and Palettes. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt.

Petrie, W.M.F. and Quibell, J. (1896) Naqada and Ballas. London: Bernard Quaritch.

Philip, G. (2002) ‘Contacts between the Uruk world and the Levant during the fourth millennium BC: evidence and interpretation’. In N. Postgate (ed.) Artefacts of Complexity: Tracking the Uruk in the Near East. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq.

Pittman, H. (1996) ‘Constructing context: the Gebel el-Arak knife: Greater Mesopotamian and Egyptian interaction in the late fourth millennium BC’. In J.S. Cooper and G.M. Schwartz (eds)

The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Winoana Lake: Eisenbrauns.

—— (2001) ‘Mesopotamia Intraregional relations reflected through glyptic evidence in the Late Chalcolithic 1–5 periods’. In M.S. Rothman (ed.) Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors. Crosscultural interactions in the era of state formation. Santa Fe: School of the American Research Press.

Podzorski, P. (1988) ‘Predynastic Egyptian seals of known provenience in the R.H. Lowie Museum of Anthropology’. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 47: 259–268.

Prag, K. (1986) ‘Byblos and Egypt in the fourth millennium B.C.’ Levant 18: 59–73. Quibell, J. and Green, F.W. (1902) Hierakonpolis II. London: Egyptian Research Account.

Rizkana, I. and Seeher, J. (1987) Maadi I. The Pottery of the Predynastic Settlement. Excavations at the Predynastic Site of Maadi and its Cemeteries conducted by Mustafa Amer and Ibrahim Rizkana on behalf of the Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts of Cairo University 1930–1953. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

—— (1989) Maadi III. The Non-Lithic Small Finds and the Structural Remains of the Predynastic Settlements. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Schwartz, G.M. (2001) ‘Syria and the Uruk expansion’. In M.S. Rothman (ed.) Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors. Cross-Cultural interactions in the era of state formation. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Serpico, M. (2000) ‘Resins, amber and bitumen’. In P. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds) Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sherratt, A.G. and Sherratt, E.S. (1991) ‘From luxuries to commodities: the nature of Mediterranean Bronze Age trading systems’. In N. Gale (ed.) Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean. Jonsered:

˚

Paul Aström.

635

–– Alice Stevenson ––

Sievertsen, U. (1992) Das Messer vom Gebel el-Arak. Baghdader Mitteilungen 23:1–75.

——(2008) ‘Niched architecture in Early Mesopotamia and Early Egypt’. In B. Midant-Reynes and Y. Tristant (eds) Egypt at its Origins 2. Leuven: Peeters Publishers.

Smith, H.S. (1992) ‘The making of Egypt: a review of the influence of Susa and Sumer on Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia in the 4th millennium B.C.’ In R. Friedman and B. Adams (eds) The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Oxford: Oxbow.

Stevenson, A. (2009) The Predynastic Egyptian cemetery of el-Gerzeh. Leuven: Peeters.

Sürenhagen, S. (1986) ‘The dry farming belt: the Uruk period and subsequent developments’. In H. Weiss (ed.), The Origin of Cities in Dry-Farming Syria and Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium B.C. Guilford: Four Quarters.

Tessier, B. (1987) ‘Glyptic evidence for a connection between Iran, Syro-Palestine and Egypt in the fourth and third millennia’. Iran 25: 27–53.

Tite, M.S. and Shortland, A. (2008) Production Technology of Faience and Related Early Vitreous Materials. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Trigger, B. (1993) Early Civilizations. Ancient Egypt in Context. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

van den Brink, E.C.M. (2001) ‘Some comments in the margins of The Origin of the Palace-Façade as Representation of Lower Egyptian Elites. Göttinger Miszellen 183: 99–111.

van Driel, G. and van Driel-Murray, C. (1979) ‘Jebel Aruda, 1977–1978’. Akkadica 33: 2–28.

von der Way, T. (1987) ‘Tell el-Fara’in Buto: 2. Bericht’. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 43: 241–257.

—— (1992) Indication of architecture with niches at Buto. In R. Friedman, and B. Adams (eds)

The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Ward, W. (1964) ‘Relations between Egypt and Mesopotamia from prehistoric times to the end of the Middle Kingdom’. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 7: 1–45, 121–35. Wengrow, D. (2006) The Archaeology of Early Egypt. Social transformations in north-east Africa, 10,000

to 2650 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkinson, T. (2002) ‘Uruk into Egypt: imports and imitations’. In N. Postgate (ed.) Artefacts of Complexity: Tracking the Uruk in the Near East. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq.

Winkler, H. (1938) Rock Drawings of Southern Upper Egypt. London: Egypt Exploration Society. Wright, H.T. and Rupley, E.S.A. (2001) ‘Calibrated radiocarbon age determinations of Uruk-related

assemblages’. In M.S. Rothman (ed.) Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors. Cross-Cultural interactions in the era of state formation. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Zarins, J. (1989) ‘Ancient Egypt and the Red Sea trade: the case for obsidian in the predynastic and Archaic periods’. In A. Leonard and B.B. Williams (eds) Essays in Ancient Civilization Presented to Helene J. Kantor. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

636