- •CONTENTS

- •PREFACE

- •ABBREVIATIONS

- •GENERAL AND COLORECTAL

- •CASE 1:

- •ANSWER 1

- •CASE 2:

- •ANSWER 2

- •CASE 3:

- •ANSWER 3

- •CASE 4:

- •ANSWER 4

- •CASE 5:

- •ANSWER 5

- •CASE 6:

- •ANSWER 6

- •CASE 7:

- •ANSWER 7

- •CASE 8:

- •ANSWER 8

- •CASE 9:

- •ANSWER 9

- •CASE 10:

- •ANSWER 10

- •CASE 11:

- •ANSWER 11

- •CASE 12:

- •ANSWER 12

- •CASE 13:

- •ANSWER 13

- •CASE 14:

- •ANSWER 14

- •CASE 15:

- •ANSWER 15

- •CASE 16:

- •ANSWER 16

- •CASE 17:

- •ANSWER 17

- •CASE 18:

- •ANSWER 18

- •CASE 19:

- •ANSWER 19

- •CASE 20:

- •ANSWER 20

- •UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL

- •CASE 21:

- •ANSWER 21

- •CASE 22:

- •ANSWER 22

- •CASE 23:

- •ANSWER 23

- •CASE 24:

- •ANSWER 24

- •CASE 25:

- •ANSWER 25

- •CASE 26:

- •ANSWER 26

- •CASE 27:

- •ANSWER 27

- •CASE 28:

- •ANSWER 28

- •CASE 29:

- •ANSWER 29

- •CASE 30:

- •ANSWER 30

- •CASE 31:

- •ANSWER 31

- •CASE 32:

- •ANSWER 32

- •CASE 33:

- •ANSWER 33

- •CASE 34:

- •ANSWER 34

- •CASE 35:

- •ANSWER 35

- •CASE 36:

- •ANSWER 36

- •BREAST AND ENDOCRINE

- •CASE 37:

- •ANSWER 37

- •CASE 38:

- •ANSWER 38

- •CASE 39:

- •ANSWER 39

- •CASE 40:

- •ANSWER 40

- •CASE 41:

- •VASCULAR

- •CASE 42:

- •ANSWER 42

- •CASE 43:

- •ANSWER 43

- •CASE 44:

- •ANSWER 44

- •CASE 45:

- •ANSWER 45

- •CASE 46:

- •ANSWER 46

- •CASE 47:

- •ANSWER 47

- •CASE 48:

- •ANSWER 48

- •CASE 49:

- •ANSWER 49

- •CASE 50:

- •ANSWER 50

- •CASE 51:

- •ANSWER 51

- •CASE 52:

- •ANSWER 52

- •CASE 53:

- •ANSWER 53

- •CASE 54:

- •ANSWER 54

- •CASE 55:

- •ANSWER 55

- •CASE 56:

- •ANSWER 56

- •UROLOGY

- •CASE 57:

- •ANSWER 57

- •CASE 58:

- •ANSWER 58

- •CASE 59:

- •ANSWER 59

- •CASE 60:

- •ANSWER 60

- •CASE 61:

- •ANSWER 61

- •CASE 62:

- •ANSWER 62

- •CASE 63:

- •ANSWER 63

- •CASE 64:

- •ANSWER 64

- •ORTHOPAEDIC

- •CASE 65:

- •ANSWER 65

- •CASE 66:

- •ANSWER 66

- •CASE 67:

- •ANSWER 67

- •CASE 68:

- •ANSWER 68

- •CASE 69:

- •Questions

- •ANSWER 69

- •CASE 70:

- •ANSWER 70

- •CASE 71:

- •ANSWER 71

- •CASE 72:

- •ANSWER 72

- •CASE 73:

- •ANSWER 73

- •CASE 74:

- •ANSWER 74

- •CASE 75:

- •ANSWER 75

- •CASE 76:

- •ANSWER 76

- •CASE 77:

- •ANSWER 77

- •CASE 78:

- •ANSWER 78

- •CASE 79:

- •ANSWER 79

- •CASE 80:

- •ANSWER 80

- •CASE 81:

- •ANSWER 81

- •EAR, NOSE AND THROAT

- •CASE 82:

- •ANSWER 82

- •CASE 83:

- •ANSWER 83

- •CASE 84:

- •ANSWER 84

- •CASE 85:

- •ANSWER 85

- •NEUROSuRGERY

- •CASE 86:

- •ANSWER 86

- •CASE 87:

- •ANSWER 87

- •CASE 88:

- •ANSWER 88

- •CASE 89:

- •ANSWER 89

- •ANAESTHESIA

- •CASE 90:

- •ANSWER 90

- •CASE 91:

- •ANSWER 91

- •CASE 92:

- •ANSWER 92

- •CASE 93:

- •ANSWER 93

- •CASE 94:

- •ANSWER 94

- •POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

- •CASE 95:

- •ANSWER 95

- •CASE 96:

- •ANSWER 96

- •CASE 97:

- •ANSWER 97

- •CASE 98:

- •ANSWER 98

- •CASE 99:

- •ANSWER 99

- •CASE 100:

- •ANSWER 100

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

CASE 95: nutrition

history

On the ward round with your consultant, you see a patient on intensive care. The patient had an emergency laparotomy for faecal peritonitis 5 days previously. He underwent a Hartmann’s procedure for a perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. He is currently being ventilated and has developed a hospital-acquired pneumonia. He is likely to require ventilation on intensive care for a number of days and the staff are concerned because he has not received any nutrition since his operation.

Questions

•What are the two main methods of providing nutrition that you may consider?

•What are the routes of administration for each type?

•What are the advantages and disadvantages of each type?

•What is a Hartmann’s procedure?

•Which method of feeding would be most appropriate in this patient?

217

100 Cases in Surgery

ANSWER 95

Malnutrition leads to delayed wound healing, reduced ventilatory capacity, reduced immunity and an increased risk of infection. The nutritional status of a patient should be assessed daily.

The two main methods of feeding are either by the enteral route or the parenteral route.

Enteral feeding is via the gastrointestinal tract. It is less expensive and is associated with fewer complications than feeding by the parenteral route. Enteral feeding stimulates the bowel and encourages the production of mucosal factors, which maintain the normal physiological barrier to bacterial translocation. Patients who can take food orally can have their diet supplemented with nutritional drinks. If patients are not able to feed orally, then nasoenteral tube feeding should be considered. Nasogastric feeding is the mostly commonly used route. Tube tips can be placed in the duodenum or jejunum if there is pathology in the proximal part of the gastrointestinal tract. In the longer term, enteral feeding can be via a feeding gastrostomy or jejunostomy. These can be placed either endoscopically, radiologically or at the time of surgery. Disadvantages are that feeding tubes can become blocked or dislodged, leading to peritonitis.

The parenteral route should only be used if there is an inability to ingest, digest, absorb or propulse nutrients through the gastrointestinal tract. It can be administered by either a peripheral or central line. Peripheral parenteral nutrition can cause thrombophlebitis due to the hyperosmotic nature of the feed. Central parenteral nutrition needs to be delivered via a large central line – in the subclavian or jugular vein. Insertion of a central line carries a significant risk of complications, e.g. pneumothorax, haematoma, nerve injury and thrombosis. Sepsis is the most frequent and serious complication of centrally administered parenteral nutrition. The other serious complication relates to metabolic derangement, which occurs in up to 5 per cent of patients on parenteral nutrition.

A Hartmann’s procedure is a safe method of removing a diseased section of large bowel. After resection, the distal part of the bowel is closed and left in situ, and the proximal end is brought to the skin as an end colostomy. There is no anastamosis, which allows enteral nutrition to be started early.

KEY POINTS

•enteral feeding is preferred to parenteral feeding.

•a patient’s nutritional status should be assessed on a daily basis.

218

Postoperative Complications

CASE 96: poStoperative pyreXia

history

As the doctor on call, you have been asked to assess an 86-year-old male patient on the ward who is 1 day post perforated peptic ulcer repair. The nurse is concerned as he has spiked a temperature. The operations note reports that there was minimal peritoneal soiling at the time of the operation. He has a morphine infusion, but his pain is poorly controlled. A urinary catheter remains from his operation and the urine output is adequate. Prior to his surgery he was fit, but he was a heavy smoker.

examination

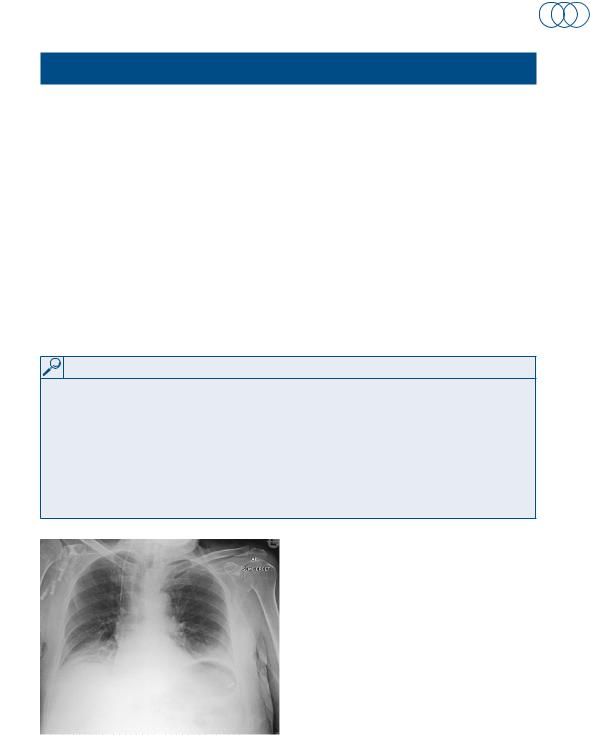

His blood pressure is 130/90 mmHg, pulse rate 110/min, respiratory rate 30/min and temperature 38°C. His saturations have remained at 99 per cent on 24 per cent oxygen. On examination of his chest, you can hear coarse basal crepitations bilaterally and the lung bases are dull on percussion. Abdominal examination reveals tenderness around the incision site and the urinalysis is clear. Blood tests and a portable chest x-ray (Figure 96.1) are ordered and shown below.

INVESTIGATIONS

|

|

Normal |

haemoglobin |

10.5 g/dl |

11.5–16.0 g/dl |

mean cell volume |

80 fl |

76–96 fl |

White cell count (WCC) |

12.2 × 109/l |

4.0–11.0 × 109/l |

platelets |

250 × 109/l |

150–400 × 109/l |

Sodium |

138 mmol/l |

135–145 mmol/l |

potassium |

3.6 mmol/l |

3.5–5.0 mmol/l |

urea |

5 mmol/l |

2.5–6.7 mmol/l |

Creatinine |

52 μmol/l |

44–80 μmol/l |

Figure 96.1 plain x-ray of the chest.

Questions

•What is the likely cause of the pyrexia in this patient?

•What are the risk factors?

•How should the patient be managed?

219

100 Cases in Surgery

ANSWER 96

The chest x-ray shows a reduction in lung volume bilaterally, and basal consolidation. The patient has basal atelectasis as a consequence of pulmonary collapse. The patient’s inability to cough leads to the failure of clearance of bronchial secretions from the lungs. Consequently, there is occlusion and collapse of the lung segments. The collapsed lung is at risk of secondary infection by inhaled organisms, leading to a pneumonia.

Atelectasis is more common in patients with pre-existing lung disease, obese patients and heavy smokers. Patients who have undergone thoracic or upper-abdominal surgery find chest expansion limited by pain, making them more prone to basal lung collapse. The patient in this case has a number of risk factors for developing basal atelectasis. He is a heavy smoker and has an upper midline incision with poor postoperative pain control.

Patients with basal atelectasis usually develop a pyrexia at about 48 h, with an accompanying tachycardia and tachypnoea. Examination reveals bronchial breathing, and reduced air entry bibasally with dullness on percussion. The chest x-ray shows consolidation and collapse in the affected areas. The patient should be treated aggressively with chest physiotherapy to prevent pneumonia. Patient position, regular nebulizers and deep breathing help to clear secretions and to keep the lungs fully expanded.

With elective operations, these patients can be identified preoperatively. A thoracic epidural, regular nebulizers and chest physiotherapy may help to prevent basal lung collapse.

KEY POINTS

•patients at risk of respiratory complications should be identified preoperatively.

•good pain control and chest physiotherapy will help prevent basal atelectasis.

220