- •THE BANK OF THE FUTURE

- •The ABCs of Digital Disruption in Finance

- •Contents

- •The Bank of the Future

- •A is for Artificial Intelligence and Automation

- •B Is for BigTech, Especially in Asia and Emerging Markets

- •C Is for Core Banking, Cloud, and Challengers

- •Where in the World?

- •Disruption by Product and Geography

- •Re-imaging versus Re-engineering Finance

- •Bank of the Future

- •Interview with Exponential View: Azeem Azhar

- •About Azeem Azhar

- •Evolution of AI – Why Now?

- •Industrialization of AI – Spending and Investing More

- •Banking & Securities Is the Largest Non-Tech Industry for AI

- •Interview with Citi Ventures: Ramneek Gupta

- •About Citi Ventures

- •About Ramneek Gupta

- •AI-driven Applications in Banking

- •Use Cases in Consumer Banking

- •Interview with Active.Ai: Ravi Shankar

- •About Active.AI

- •About Ravi Shankar

- •Use Cases in Commercial Banking

- •Use Cases in Capital Markets Banking

- •Interview with Behavox: Erkin Adylov

- •About Behavox

- •About Erkin Adylov

- •AI Enables FTE Reduction, Optimizes Distribution

- •Chinese BigTech and Financial Services

- •[A] Ant Financial Builds an Empire of Services

- •[B] Tencent's WeChat Is China's App for Everything

- •Interview with Kapronasia: Zennon Kapron

- •About Kapronasia

- •About Zennon Kapron

- •China and India on Different FinTech Paths

- •India on the Frontline of Digital Finance

- •India's Transformation Towards Digital

- •Google's m-wallet (Tez) Sees Early Success

- •New RBI Directive Could Threaten Digital Payments

- •About Aditya Menon

- •GAFAs at the Gate with PSD2; But Do Bank Clients Care?

- •What is PSD2?

- •The New Banking Model under PSD2

- •U.K.'s Open Banking Standard

- •Impact of PSD 2/Open Banking on Banks – Risk of Disintermediation?

- •Chapter C: Core Banking, Cloud and Challengers

- •Challenge of Legacy Core Banking Systems

- •Banks Face Multiple Pain Points

- •Do Banks Need To Update Core Systems?

- •IT Change: Incumbents, Neobanks and Vendors’ Views

- •[A] The Incumbent Banks’ View

- •[B] The Neobanks’ View

- •Case Study: Leveris Banking Core

- •Journey to the Cloud

- •Cloud Ecosystem – The Vision for Hardware, Applications and Data

- •There Are Many Different Ways to Move Applications to the Cloud…

- •Some Application Workloads Are Easier to Move to Cloud than Others

- •And Core Banking Applications Are the Hardest to Address

- •Interview with Ping An: Jonathan Larsen

- •About Jonathan Larsen

- •Chapter D: Digital Assets

- •Bitcoin, Blockchain and All Things Crypto

- •Internet vs. Blockchain Financial Value Capture

- •2017: The Year of Crypto

- •Who is Buying Bitcoins?

- •2018: The Year of Second-Layer Protocols?

- •About PwC – FinTech and RegTech Team

- •About Henri Arslanian

- •Blockchain Applications

- •A.] The Power of Smart Contracts

- •B.] KYC-Chain and Digital Identity

- •C.] Reg-Tech

- •D.] ICOs – A Risky New Paradigm?

- •Regulatory approach to ICOs differ significantly across countries

- •Regulatory Approaches to Bitcoin

- •About King & Wood Mallesons

- •About Urszula McCormack

- •What is Ripple? How is it Different?

- •Ripple XRP – The Cryptocurrency

- •Banks and the Ripple Protocol

- •How Are Central Bank Cryptocurrencies Different

- •What Are Central Bankers Saying on CBCCs?

- •Epilogue: Emerging Market BRATs beyond China and India

- •Introducing the BRATs

- •A.] Share Unique Banking Sector Characteristics

- •B.] Favorable Demographics

- •C.] Technology Enablers

- •FinTech Investments Trends

- •About Vostok Emerging Finance

- •About David Nangle

- •NOW / NEXT

- •Contents

- •Investment summary

- •Reporting schedule

- •Earnings revisions

- •Reporting trends: 2H18E vs 2H17

- •Reporting trends 2H18E vs 1H18

- •Results previews

- •Commodity price and exchange rate forecasts

- •Peer comp charts

- •African Rainbow Minerals

- •Alrosa

- •Anglo American

- •Assore

- •Exxaro

- •Glencore

- •Kumba Iron ore

- •NorNickel

- •Rio Tinto

- •Rusal

- •Vale

- •Gold Fields

- •Harmony

- •Polymetal

- •Anglo American Platinum

- •Lonmin

- •Northam

- •Royal Bafokeng Platinum

- •Acron

- •PhosAgro

- •Evraz

- •Disclosures appendix

vk.com/id446425943 |

|

123 |

March 2018 |

Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions |

NOW / NEXT

Key Insights regarding the future of Banking

|

INNOVATION |

Large incumbent banks lag digital natives and their technology stacks are struggling |

|

|

|

to compete in a world that is mobile first. / Banks are exploring AI uses in consumer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and wholesale banking with the help of robotics (automation of routine tasks), |

|

|

|

analytics (big data mining), chat bots (digital dialogue with customers), and |

|

|

|

cognitive (changing rules and adapting). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TECHNOLOGY |

Today’s global payment infrastructure moves money from one payment system to |

|

another through a series of internal transfers across institutions which makes the |

|

system slow, error prone, and costly. / The use of Blockchain will enable direct |

|

transfer of digital assets without the need for an intermediary or a centralized |

|

authority plus smart contracts/tokenization that can automate and execute pre- |

|

agreed conditions once they are met. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SHIFTING WEALTH |

The old question was whether new entrants — FinTech startups — were going to |

|

|

|

|

|

nibble away at incumbent bank’s profit. / The new question is how to stop |

|

|

|

|

|

established tech giants — BigTech — leveraging their strong customer bases, vast |

|

|

|

|

|

user data pools, agile tech platforms, and deep funding pools to disrupt banks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2018 Citigroup

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions |

© 2018 Citigroup |

www.citi.com/citigps |

|

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Central Bank of Russia

Wait-and-see mode

Update

Economic Research

5 February 2019

Economics

Russia

Oleg Kouzmin

+7 (495) 258-7770 x 4506 OKouzmin@rencap.com

On Friday (8 February), we expect the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) to keep the key interest rate at 7.75%. We expect no more rate hikes if inflation peaks at <6% in March-April and geopolitical risks do not increase in 1Q19.

We expect the CBR to keep the rate at 7.75% on Friday

The policy statement is due to be published at 1:30pm Moscow time (10:30am London time) on 8 February. We believe the CBR will keep the key rate unchanged, in line with Bloomberg consensus. After the previous meeting on 14 December, the CBR noted that it will assess the need for future policy tightening depending on inflation and economic developments, and external risks. We believe the CBR will maintain rates at the upcoming meeting just to see how inflation dynamics and its forecasts are affected by the recent VAT increase. We see a rise in inflation expectations – which we believe is expected by the CBR and the market (Figure 2).

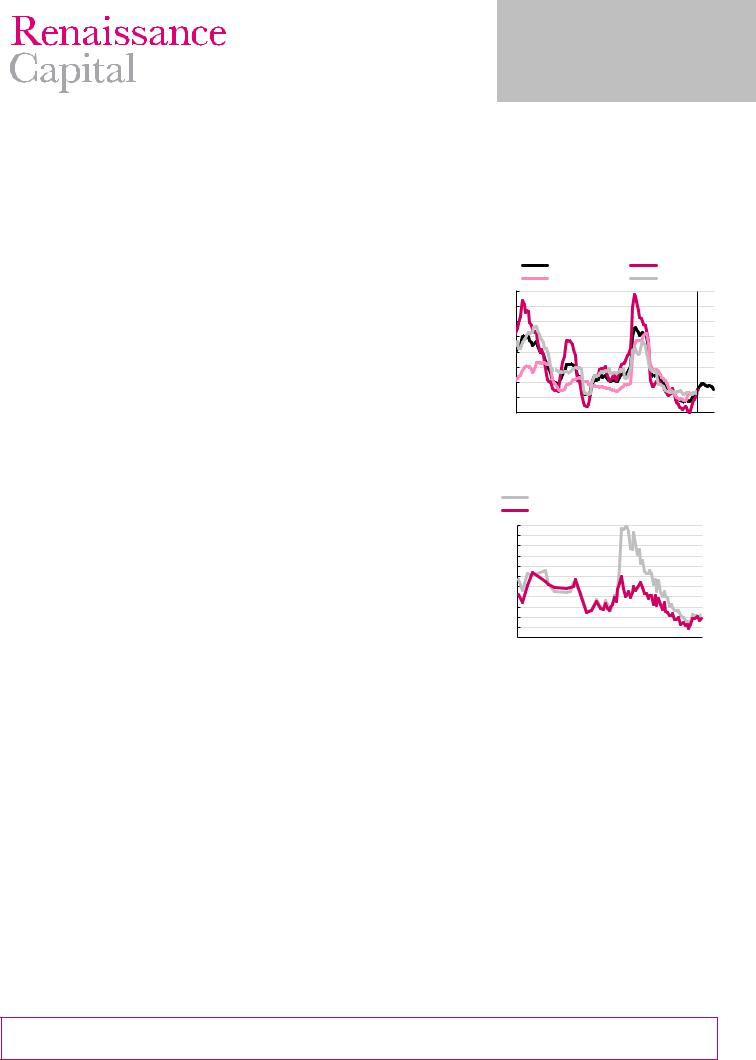

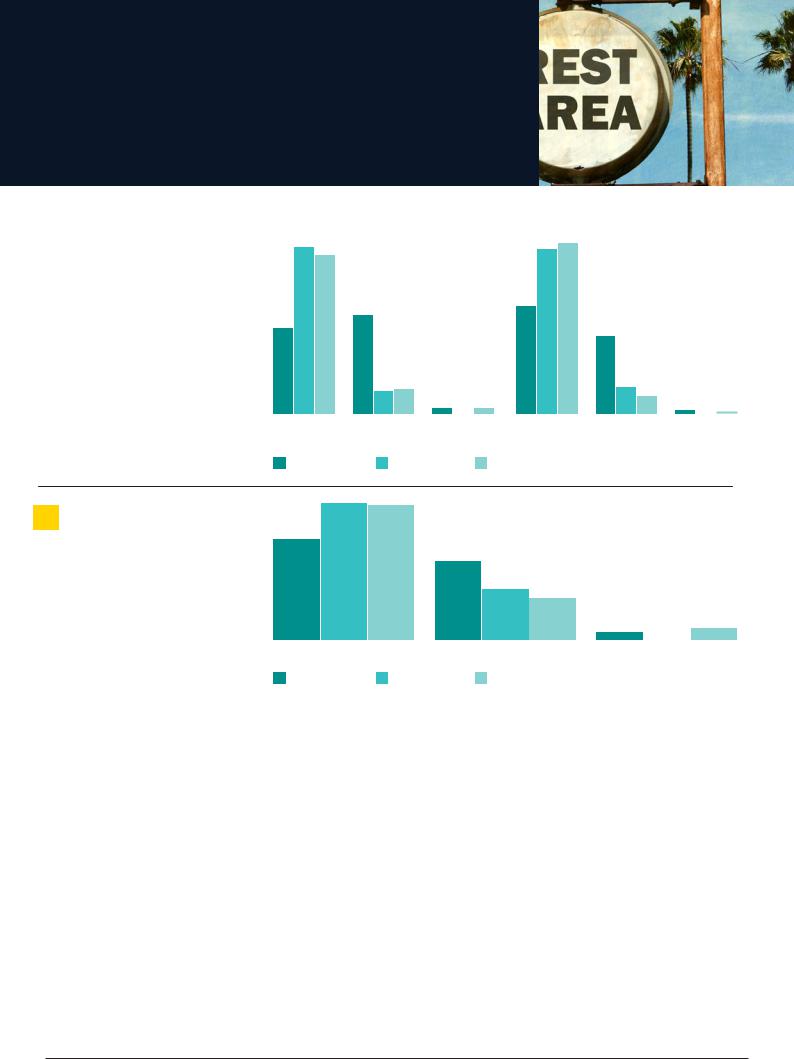

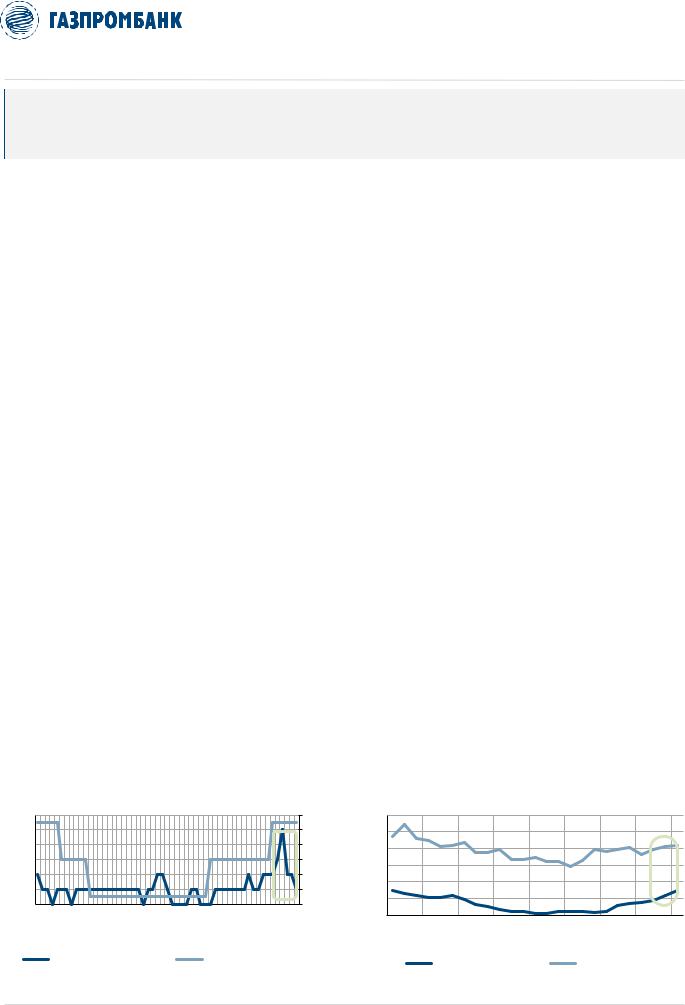

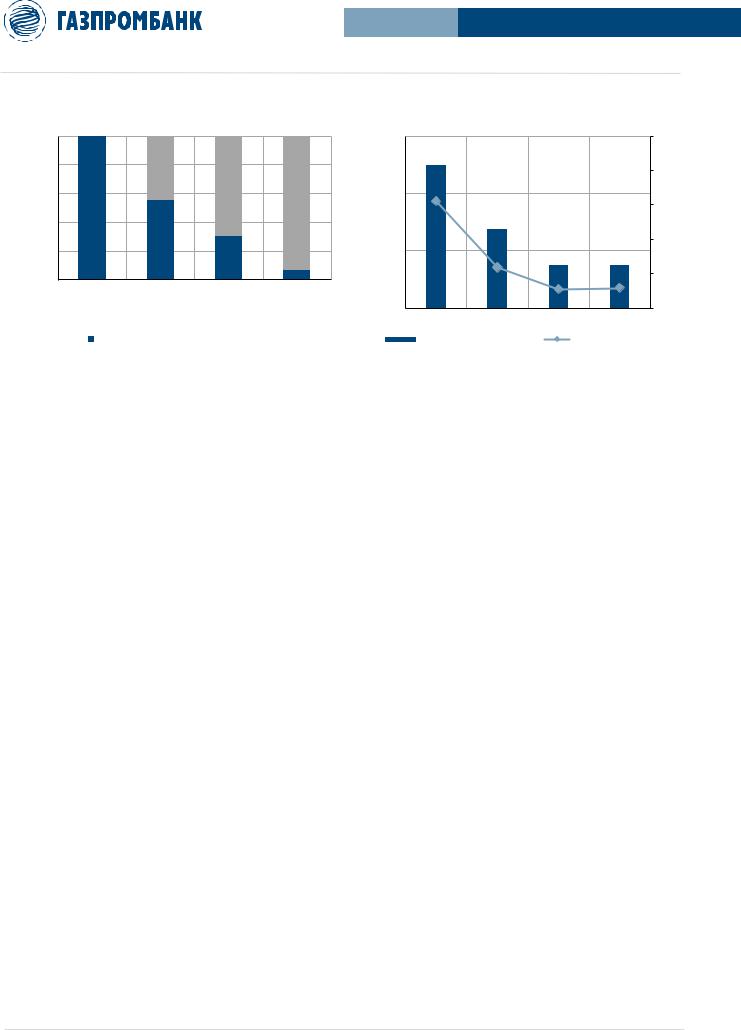

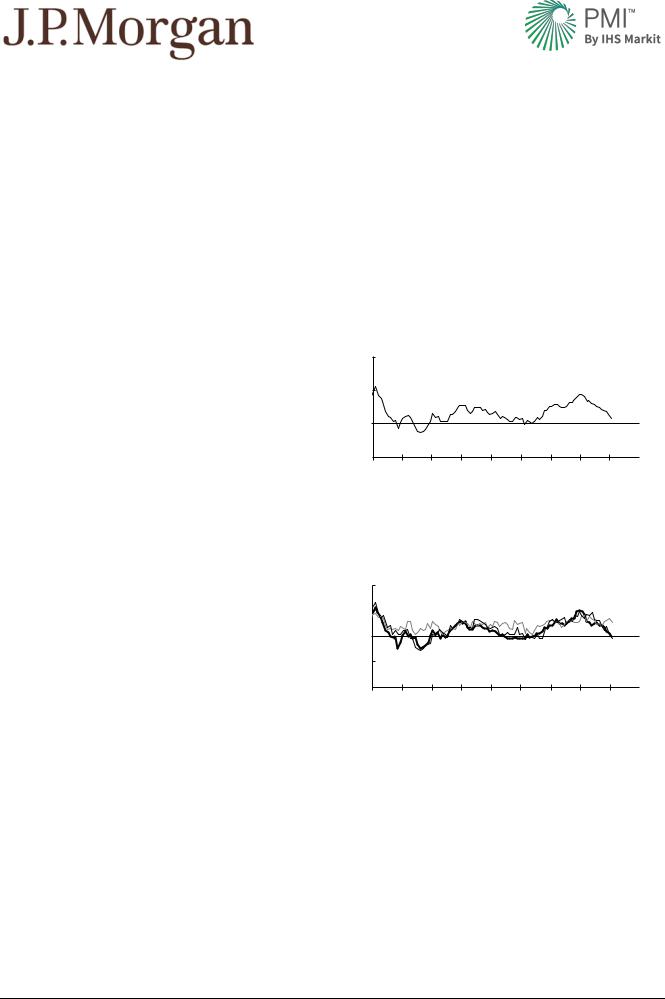

Figure 1: CPI and its components, % YoY

|

CPI |

|

|

Food |

|

|

Non-food |

|

Services |

||

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

2010 |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

Source: Rosstat, Renaissance Capital

No more hikes needed if CPI peaks at <6%

We believe future rate hikes could be avoided if headline inflation does not approach 6% in March-April (our forecast: it peaks at 5.6-5.7%). This could be a sign that inflation will only accelerate due to direct supply-side effects, while indirect effects (such as an acceleration of inflation due to worsening inflation expectations) remain muted meaning that future inflation trends remain under control (especially under cooling consumer demand growth).

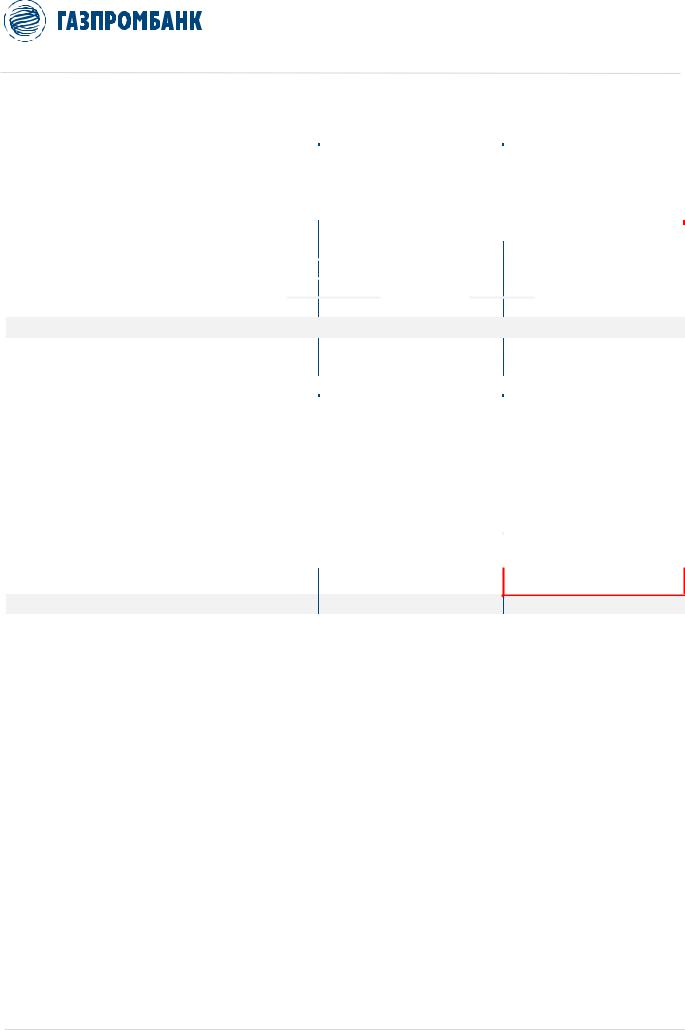

Potential sanctions are a major unknown

If we are wrong about the inflation forecast, and then the CBR makes another 25-bpt rate hike in March, it will definitely mark the end of the rate-hiking cycle, in our view…unless new sanctions arrive. Possible sanctions remain a major unknown, especially after newly elected members join the US Congress in 1Q19 and ahead of the Ukrainian presidential elections due on 31 March 2019. As our scenario analysis shows (Figures 3 and 8), if sanctions hurt Russia and the oil price remains close to current levels ($65/bl), then the rate might range from 9.25% to 11.5% at end-2019.

Russian 2018 GDP growth surprised positively (2.3%)

On 4 February, Rosstat reported that in 2018 Russian GDP expanded at the fastest pace in six years (2.3%). From the demand-side, the print was supported by a further acceleration of exports (6.3%) and stronger net domestic consumption (excluding imports). The sector breakdown shows that Russian growth primarily benefited from revised data of construction activity (5%), as well as the mining sector (4%), higher commodity prices supporting the financial sector (6%) and the World Cup, with hotels/restaurants up by 6%. We forecast that this year’s growth should be softer

(1.2%), while 2020 growth accelerates to 2.4%. In contrast with some media reports, we would not question the quality of the 2018 print. First, while late and significant data revisions are inconvenient, we do not think that a 2.3% GDP print is unachievable considering the dynamics of the second-tier economic indicators. Second, we note that although a preliminary estimate of c. 1.5% growth in 9M18 looked at odds and weaker than other indicators suggested, this disparity to the weaker side did not raise an issue of data credibility among the public.

Figure 2: Inflation expectations (direct)

Observed inflation, % YoY

Inflation expected in the next 12 months, % YoY

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apr-10 |

Apr-11 |

Apr-12 |

Apr-13 |

Apr-14 |

Apr-15 |

Apr-16 |

Apr-17 |

Apr-18 |

Source: CBR, FOM

Figure 3: Scenarios for contagion effects of potential sanctions on Russian state debt

Brent oil, $/bl |

|

65 |

|

‘Soft’ |

‘Hard’ |

Real GDP growth |

0.5% |

-0.8% |

RUB/$, annual avg |

70.8 |

75.7 |

Inflation, annual avg |

6.3% |

8.2% |

Policy rate by year-end |

9.25% |

11.5% |

Brent oil, $/bl |

50 |

80 |

||

|

‘Soft’ |

‘Hard’ |

‘Soft’ |

‘Hard’ |

Real GDP growth |

0.1% |

-1.3% |

0.8% |

-0.4% |

RUB/$, annual avg |

76.6 |

84.0 |

66.4 |

70.2 |

Inflation, annual avg |

8.2% |

11.0% |

5.5% |

6.2% |

Policy rate by year-end |

11.5% 14.0% |

8.25% 9.0% |

||

Source: Renaissance Capital estimates

© 2019 Renaissance Securities (Cyprus) Limited. All rights reserved. Regulated by the Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission (Licence No: KEPEY 053/04). Hyperlinks to important information accessible at www.rencap.com: Disclosures and Privacy Policy, Terms & Conditions, Disclaimer.

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Renaissance Capital

5 February 2019

Central Bank of Russia

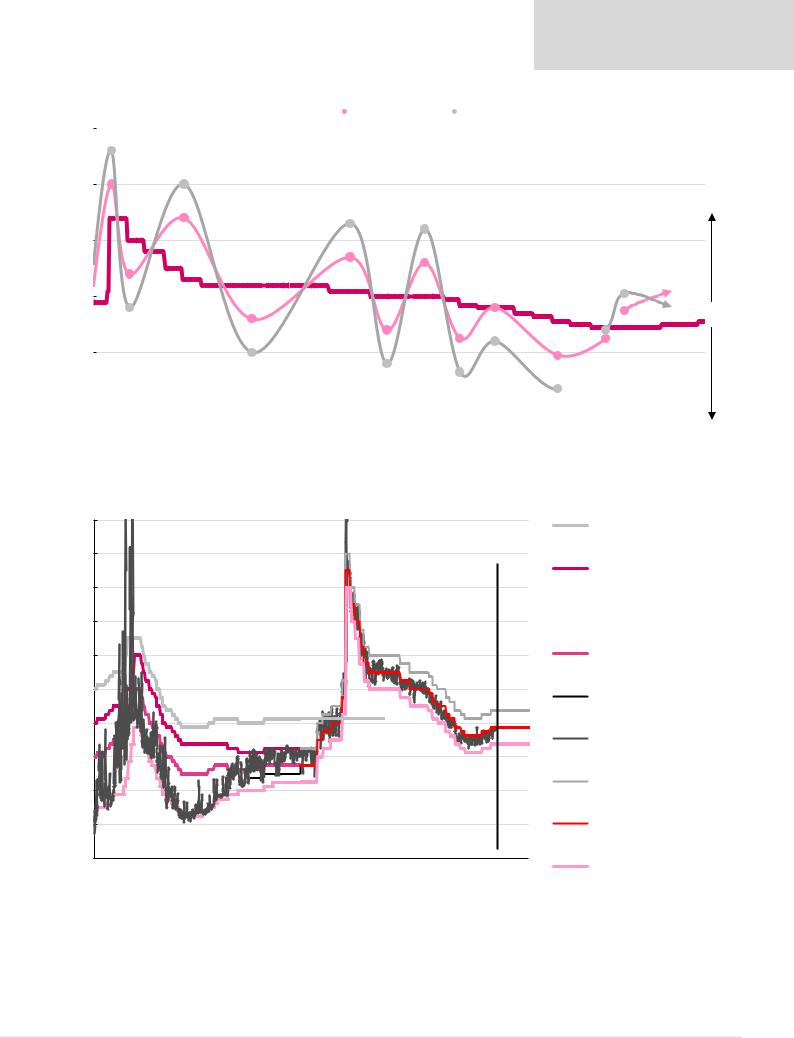

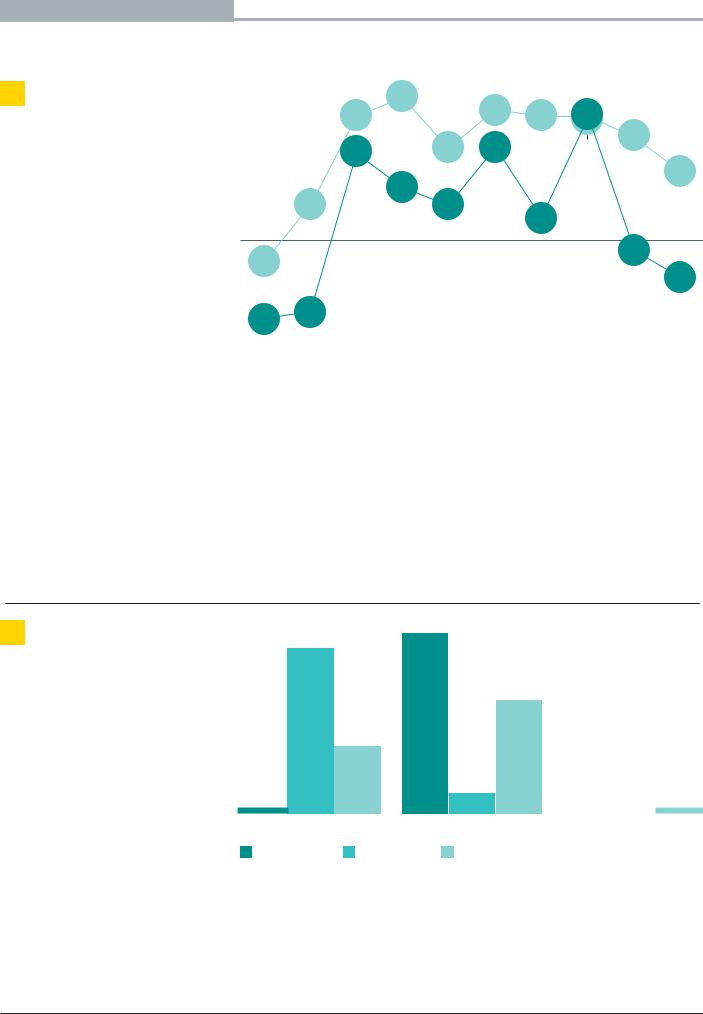

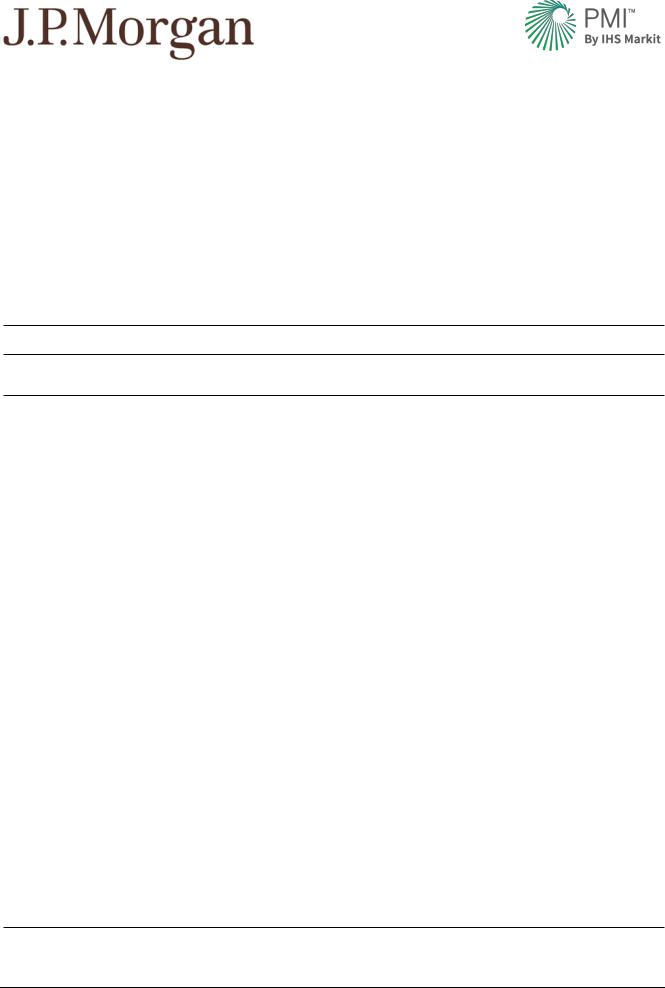

Figure 4: Cycles in the CBR’s policy stance (‘CBR mood’ in the chart, which we think tends to be exaggerated by market economists/analysts)

25 |

|

|

The CBR key rate |

|

|

'CBR mood' |

|

|

|

'Consensus interpretation' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dec 14: 'No rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

cuts until June!' |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Mid-15: 'The CBR are cutting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

20 |

slowly - not many cuts this year!' |

Mid-16: 'Rate cuts would be |

Start-17: 'Budget rule puts |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

limited - no budget |

pressures on the rouble |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

consolidation strategy!' |

and reduces the scope for |

|

2H18: |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the rate cuts!' |

|

|

|||

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

another |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jun 18: |

sanctions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mid-17: inflation 'spikes' |

& two front |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

announcement |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

to 4.4% due to delayed |

of VAT |

loaded |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

harvest supplies |

rate hikes |

||

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

increase |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jan 15: 'This is too early to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

cut rates - the CBR gives up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apr 18: new |

|

||

5 |

inflation targeting!' |

|

|

End-16: 'Rate cuts |

|

Apr 17: 'The rouble |

|

sanctions |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

End-15: 'Inflation would be crushed very |

|

is strong and |

4Q17-1Q18: front- |

|

||||||||

|

will happen soon as |

inflation is nearly at |

|

||||||||||

|

soon, and we'll see a 400 bps rate cuts as |

loaded rate cuts with |

|

||||||||||

|

the CBR lifts an oil |

|

4% - more cuts |

|

|||||||||

|

the CBR targets a 3% real policy rate!' |

|

CPI at 2-3% |

|

|||||||||

|

price outlook!' |

|

happeing soon!' |

|

|||||||||

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nov-14 Feb-15 May-15 Aug-15 Nov-15 Feb-16 May-16 |

|

Aug-16 Nov-16 Feb-17 |

May-17 Aug-17 Nov-17 Feb-18 |

May-18 Aug-18 |

Nov-18 |

||||||||

Too hawkish

Too dovish

Note: Consensus interpretation could be exaggerated in this chart; LHS shows CBR key rate in %; RHS is not a numerical axis.

Source: CBR, Renaissance Capital

Figure 5: CBR interest rate corridor and RUONIA rate, %

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

The CBR refinancing rate

The CBR stand-by REPO rate

The CBR stand-by deposit rate

The CBR stand-by deposit rate

The CBR minimum REPO rate

The CBR maximum deposit auction rate

Interbank market O/N rate (RUONIA / MIACR)

The unified rate on o/n stand-by refinancing operations

The CBR key rate

The CBR stand-by deposit rate

Source: CBR, Renaissance Capital

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

2 |

|

vk.com/id446425943

Renaissance Capital

5 February 2019

Central Bank of Russia

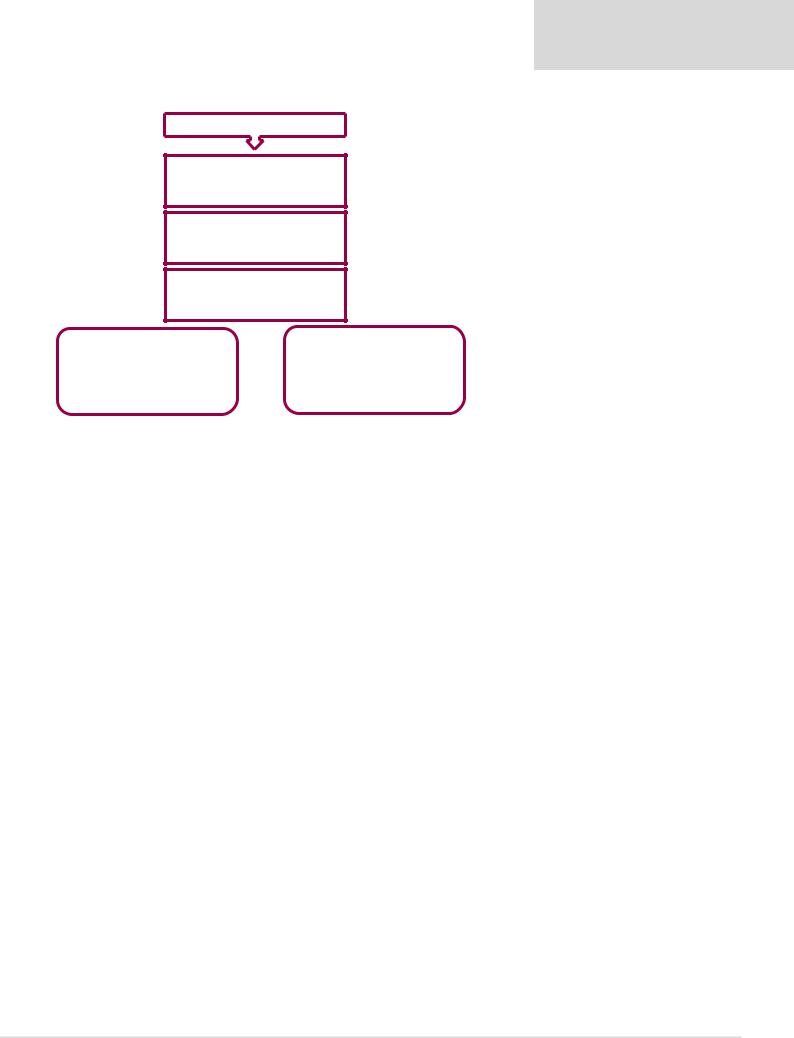

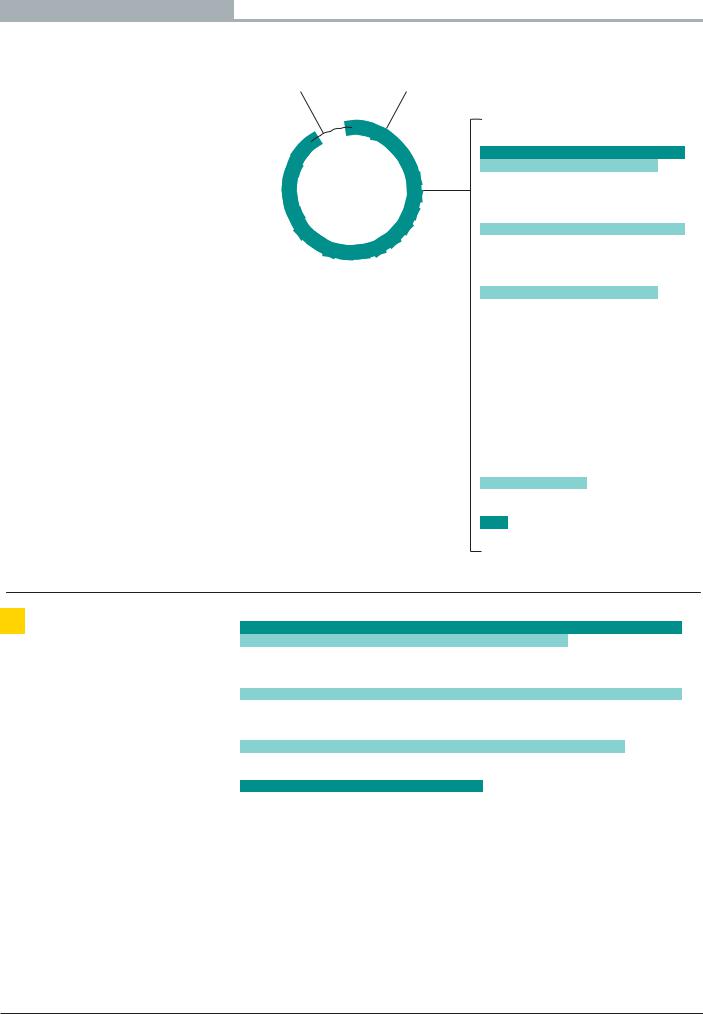

Figure 6: Approaches to calculate a neutral policy rate

Real ‘neutral’ rate

Equilibrium foreign policy rate (average between US & eurozone)

0.5-1.0%

Russian risk premium (CDS / Eurobond spreads)

1.0-1.5%

RUB REER depreciation

0-0.5%

1.5-3.0% (real rate) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.5-3.0% (real rate) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4% inflation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4%-plus inflation expectations |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.5-7.0% nominal rate |

|

|

|

|

|

5.5-7.0%-plus nominal rate |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Renaissance Capital |

||||

Figure 7: Oil scenarios for Russia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Year |

|

2018E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2019E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2020E |

||

Brent oil, $/bl |

|

|

72 |

|

90 |

80 |

70 |

65 |

|

60 |

|

55 |

50 |

|

40 |

|

30 |

|

60 |

||

|

|

|

Base case |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Real GDP growth |

|

|

2.3% |

|

1.8% |

|

1.5% |

1.3% |

1.2% |

|

1.1% |

0.9% |

0.6% |

|

0.3% |

|

-1.4% |

2.4% |

|||

RUB/$, annual avg |

|

|

62.8 |

|

60.8 |

63.9 |

65.6 |

66.3 |

|

67.4 |

69.8 |

71.1 |

|

73.2 |

|

81.0 |

68.5 |

||||

Inflation, annual avg |

|

|

2.9% |

|

5.0% |

|

5.1% |

5.3% |

5.4% |

|

5.5% |

5.8% |

6.1% |

|

6.7% |

|

8.4% |

3.8% |

|||

Policy rate by year-end |

|

|

7.75% |

|

7.5% |

7.5% |

7.5% |

7.75% |

|

7.75% |

8.0% |

8.5% |

|

11.0% 13.0% |

7.25% |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Current account, % of GDP |

|

|

6.7% |

|

7.3% |

6.6% |

5.7% |

5.4% |

|

4.9% |

4.8% |

3.9% |

|

2.4% |

|

3.0% |

4.1% |

||||

Budget balance, % of GDP |

|

|

2.0% |

|

4.1% |

|

3.4% |

2.5% |

2.0% |

|

1.5% |

0.8% |

0.5% |

|

-0.6% |

-2.0% |

0.8% |

||||

GDP, $bn |

|

|

1,629 |

1,845 |

1,723 |

1,641 |

1,618 |

|

1,574 |

1,365 |

1,456 |

|

1,364 |

|

1,172 |

1,643 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Renaissance Capital estimates |

||||||

Figure 8: Potential impact of new sanctions on Russian macro |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2019E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Brent oil, $/bl |

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

65 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Base |

‘Soft’ |

|

‘Hard’ |

Base |

‘Soft’ |

|

‘Hard’ |

|

Base |

‘Soft’ |

‘Hard’ |

|||||||||

|

case Sanctions sanctions |

case Sanctions sanctions |

case |

Sanctions sanctions |

|||||||||||||||||

Real GDP growth |

1.5% |

0.8% |

|

-0.4% |

1.2% |

0.5% |

|

-0.8% |

|

0.6% |

|

0.1% |

|

-1.3% |

|||||||

RUB/$, annual avg |

63.9 |

66.4 |

|

|

|

70.2 |

66.3 |

70.8 |

|

75.7 |

|

71.1 |

|

76.6 |

|

84.0 |

|||||

Inflation, annual avg |

5.1% |

5.5% |

|

6.2% |

5.4% |

6.3% |

|

8.2% |

|

6.1% |

|

8.2% |

|

11.0% |

|||||||

Policy rate by year-end |

7.5% |

8.25% |

9.0% |

7.75% |

9.25% |

|

11.5% |

|

8.5% |

|

11.5% |

|

14.0% |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Current account, $bn |

113 |

138 |

|

|

|

158 |

87 |

109 |

|

128 |

|

|

57 |

|

77 |

|

|

|

100 |

||

% of GDP |

6.6% |

10.1% |

|

8.3% |

5.4% |

7.1% |

|

8.9% |

|

3.9% |

|

5.6% |

|

7.9% |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

External debt, $bn |

459 |

454 |

|

|

|

447 |

453 |

445 |

|

438 |

|

444 |

|

436 |

|

|

427 |

||||

% of GDP |

27% |

27% |

|

|

|

28% |

28% |

29% |

|

30% |

|

30% |

|

32% |

|

33% |

|||||

FX reserves, $bn |

572 |

564 |

|

|

|

550 |

544 |

531 |

|

522 |

|

514 |

|

507 |

|

|

502 |

||||

Months of imports cover |

25 |

26 |

|

|

|

26 |

26 |

27 |

|

27 |

|

|

27 |

|

28 |

|

|

|

30 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

Budget balance, % of GDP |

3.4% |

3.7% |

4.2% |

2.0% |

2.4% |

|

3.0% |

|

0.5% |

|

1.0% |

|

1.6% |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

GDP, RUBtrn |

110.1 |

110.1 |

110.3 |

107.3 |

108.1 |

|

109.2 |

|

103.5 |

|

105.3 |

|

107.1 |

||||||||

GDP, $bn |

1,723 |

1,659 |

|

1,572 |

1,618 |

1,526 |

|

1,443 |

|

1,456 |

|

1,375 |

|

1,274 |

|||||||

Source: Renaissance Capital estimates

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

3 |

|

vk.com/id446425943

Renaissance Capital

5 February 2019

Central Bank of Russia

Figure 9: Russia – key economic indicators

Ratings (M/S&P/F): Ba1/BBB-/BBB- |

EODB Rank: 31 (35) – Strong |

Corruption Rank: 135 (131) – Weak |

RenCap Legal score: 50 (56) – Middle |

|

|||||||||||||

|

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018E |

2019E |

2020E |

||

Activity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP (% YoY) |

8.2 |

8.5 |

5.2 |

-7.8 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

3.5 |

1.3 |

0.7 |

-2.5 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

||

Private consumption (% YoY) |

|

12.2 |

14.3 |

10.6 |

-5.1 |

5.1 |

6.8 |

7.9 |

5.2 |

2.0 |

-9.4 |

-1.9 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

3.5 |

|

Government consumption (% YoY) |

2.3 |

2.7 |

3.4 |

-0.6 |

-1.5 |

1.4 |

2.6 |

0.9 |

-2.1 |

-3.1 |

1.4 |

2.5 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

||

Investment (% YoY) |

|

16.7 |

21.0 |

10.6 |

-14.4 |

5.9 |

9.1 |

5.0 |

1.3 |

-1.8 |

-11.2 |

0.7 |

5.5 |

2.3 |

1.5 |

3.6 |

|

Industrial production (% YoY) |

6.3 |

6.8 |

0.8 |

-9.2 |

8.3 |

4.8 |

2.5 |

0.3 |

1.7 |

-3.4 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

||

Unemployment rate (% YoY) |

|

7.2 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

8.4 |

7.5 |

6.6 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

5.9 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

|

Nominal GDP (RUBbn) |

26,917 |

33,248 |

41,277 |

38,807 |

46,309 60,283 68,164 73,134 79,200 |

83,101 |

86,010 |

92,089 102,245 107,303 112,552 |

|||||||||

Nominal GDP ($bn) |

|

990 |

1,299 |

1,658 |

1,224 |

1,523 |

2,050 |

2,199 |

2,293 |

2,052 |

1,353 |

1,285 |

1,579 |

1,628 |

1,618 |

1,643 |

|

Population (mn) |

142.8 |

142.8 |

142.7 |

142.9 |

142.9 |

143.0 |

143.3 |

143.3 |

143.7 |

146.8 |

147.1 |

147.4 |

147.7 |

147.9 |

148.1 |

||

GDP per capita ($) |

|

6,930 |

9,095 |

11,617 |

8,567 |

10,660 |

14,339 |

15,344 |

15,999 |

14,278 |

9,220 |

8,733 |

10,711 |

11,020 |

10,943 |

11,094 |

|

Gross domestic saving (% of GDP) |

29.0 |

29.3 |

28.8 |

19.4 |

24.4 |

29.2 |

27.8 |

24.6 |

25.0 |

26.8 |

25.9 |

26.5 |

27.3 |

27.8 |

27.3 |

||

Stock of bank credit to corp/ |

|

8,183 |

12,506 |

16,527 |

16,116 |

18,148 |

23,266 |

27,709 |

32,456 |

40,866 |

43,985 |

40,939 |

42,366 |

47,275 |

51,057 |

57,184 |

|

households (RUBbn) |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Stock of bank credit to corp/ |

30.4 |

37.6 |

40.0 |

41.5 |

39.2 |

38.6 |

40.6 |

44.4 |

51.6 |

52.9 |

47.6 |

46.0 |

46.2 |

47.6 |

50.8 |

||

households (% of GDP) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Deposits (RUBbn) |

|

8,340 |

11,890 |

14,749 |

17,131 |

21,081 |

26,082 |

30,120 |

34,931 |

43,814 |

51,907 |

50,003 |

53,703 |

60,147 |

65,561 |

72,117 |

|

Loan-to-deposit ratio |

98.1 |

105.2 |

112.1 |

94.1 |

86.1 |

89.2 |

92.0 |

92.9 |

93.3 |

84.7 |

81.9 |

78.9 |

78.6 |

77.9 |

79.3 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CPI (average % YoY) |

|

9.7 |

9.0 |

14.1 |

11.7 |

6.9 |

8.4 |

5.1 |

6.8 |

7.8 |

15.6 |

7.1 |

3.7 |

2.9 |

5.4 |

3.8 |

|

CPI (end-year % YoY) |

9.0 |

11.9 |

13.3 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

6.1 |

6.6 |

6.5 |

11.4 |

12.9 |

5.4 |

2.5 |

4.3 |

4.7 |

3.8 |

||

Nominal wages (monthly), RUB |

|

10,634 |

13,593 |

17,290 |

18,639 |

20,952 |

23,369 |

26,629 |

29,792 |

32,495 |

34,030 |

36,709 |

39,167 |

43,162 |

46,615 |

50,344 |

|

Wage rates (% YoY, nominal) |

24.3 |

27.8 |

27.2 |

7.8 |

12.4 |

11.5 |

14.0 |

11.9 |

9.1 |

4.7 |

7.9 |

6.7 |

10.2 |

8.0 |

8.0 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fiscal balance

Consolidated government balance (% of GDP)

Total public debt (% of GDP)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.4 |

5.4 |

4.1 |

-5.9 |

-3.5 |

1.6 |

0.0 |

-0.8 |

-0.5 |

-2.6 |

-3.4 |

-1.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

0.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11.1 |

9.1 |

7.8 |

11.1 |

11.7 |

11.0 |

9.9 |

13.0 |

14.8 |

15.7 |

16.5 |

15.5 |

14.2 |

15.2 |

16.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

External balance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exports ($bn) |

304.0 |

354.0 |

472.0 |

303.0 |

401.0 |

522.0 |

528.0 |

523.3 |

493.6 |

341.5 |

282.0 |

353.7 |

434.1 |

406.8 |

389.7 |

|

Imports ($bn) |

164.0 |

223.0 |

292.0 |

192.0 |

249.0 |

324.0 |

335.7 |

341.3 |

308.0 |

193.0 |

192.0 |

237.9 |

253.4 |

253.7 |

257.9 |

|

Trade balance ($bn) |

140.0 |

131.0 |

180.0 |

111.0 |

152.0 |

198.0 |

192.3 |

182.0 |

185.6 |

148.5 |

90.0 |

115.8 |

180.7 |

153.1 |

131.8 |

|

Trade balance (% of GDP) |

14.1 |

10.1 |

10.9 |

9.1 |

10.0 |

9.7 |

8.7 |

7.9 |

9.0 |

11.0 |

7.0 |

7.3 |

11.1 |

9.5 |

8.0 |

|

Current account balance ($bn) |

94.7 |

77.8 |

103.5 |

48.6 |

67.5 |

97.3 |

71.3 |

33.4 |

57.5 |

67.8 |

24.5 |

33.3 |

109.0 |

87.2 |

67.0 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

9.6 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

4.0 |

4.4 |

4.7 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

6.7 |

5.4 |

4.1 |

|

Gross FDI ($bn) |

37.6 |

55.9 |

74.8 |

36.6 |

43.2 |

55.1 |

50.6 |

69.2 |

22.0 |

6.9 |

32.5 |

28.6 |

15.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

Gross FDI (% of GDP) |

3.8 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

3.0 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

2.5 |

1.8 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Current account balance plus FDI (% of |

13.4 |

10.3 |

10.8 |

7.0 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

5.5 |

4.5 |

3.9 |

5.5 |

4.4 |

3.9 |

7.6 |

6.1 |

4.8 |

|

GDP) |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Exports (% YoY, value) |

24.6 |

16.4 |

33.3 |

-35.8 |

32.3 |

30.2 |

1.1 |

-0.9 |

-5.7 |

-30.8 |

-17.4 |

25.4 |

22.7 |

-6.3 |

-4.2 |

|

Imports (% YoY, value) |

31.2 |

36.0 |

30.9 |

-34.2 |

29.7 |

30.1 |

3.6 |

1.7 |

-9.8 |

-37.3 |

-0.5 |

23.9 |

6.5 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

Foreign exchange reserves ($bn) |

304 |

479 |

427 |

439 |

479 |

499 |

538 |

430 |

385 |

368 |

378 |

433 |

467 |

544 |

587 |

|

Import cover (months of merchandise imports) |

22.2 |

25.8 |

17.5 |

27.4 |

23.1 |

18.5 |

19.2 |

15.1 |

15.0 |

22.9 |

23.6 |

21.8 |

22.1 |

25.7 |

27.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Debt indicators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gross external debt year-end ($bn) |

313 |

464 |

480 |

466 |

489 |

539 |

636 |

716 |

600 |

518 |

512 |

518 |

456 |

453 |

438 |

|

Gross external debt (% of GDP) |

32 |

36 |

29 |

38 |

32 |

26 |

29 |

31 |

29 |

38 |

40 |

33 |

28 |

28 |

27 |

|

Gross external debt (% of exports) |

103 |

131 |

102 |

154 |

122 |

103 |

121 |

137 |

122 |

152 |

181 |

146 |

105 |

111 |

112 |

|

Total debt service ($bn) |

109.1 |

171 |

167 |

154.4 |

158 |

177 |

205 |

230 |

179 |

128 |

134 |

137 |

140 |

135 |

131 |

|

Total debt service (% of GDP) |

11 |

13 |

10 |

13 |

10 |

9 |

9 |

10 |

9 |

9 |

10 |

9 |

9 |

8 |

8 |

|

Total debt service (% of exports) |

36 |

48 |

35 |

51 |

39 |

34 |

39 |

44 |

36 |

37 |

47 |

39 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interest & exchange rates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Broad money supply (% YoY) |

48.7 |

43.5 |

0.8 |

17.7 |

31.1 |

22.3 |

11.9 |

14.6 |

2.2 |

11.4 |

9.2 |

9.5 |

10.5 |

8.5 |

11.0 |

|

Refinancing rate year-end (%) |

11.0 |

10.0 |

13.0 |

8.75 |

7.75 |

8.00 |

8.25 |

8.25 |

8.25 |

8.25 |

10.0 |

7.75 |

7.75 |

7.75 |

7.25 |

|

REPO rate year-end (%) |

6.5 |

6.5 |

9.5 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

5.25 |

5.50 |

5.50 |

17.0 |

11.0 |

10.0 |

7.75 |

7.75 |

7.75 |

7.25 |

|

Deposit rate year-end (%) |

2.3 |

2.8 |

7.25 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

4.00 |

4.25 |

4.50 |

16.0 |

10.0 |

9.0 |

6.75 |

6.75 |

6.75 |

6.25 |

|

3-month interest rate (MosPrime avg %) |

5.1 |

5.9 |

9.8 |

13.7 |

4.3 |

5.1 |

7.1 |

7.00 |

10.5 |

13.8 |

11.2 |

9.3 |

7.6 |

7.8 |

7.5 |

|

3-month rates minus $-LIBOR |

-0.1 |

0.6 |

6.8 |

13.0 |

4.0 |

4.8 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

10.3 |

13.5 |

10.4 |

8.0 |

5.3 |

4.8 |

4.4 |

|

Exchange rate (RUB/$) year-end |

26.3 |

24.5 |

29.4 |

30.2 |

30.5 |

32.1 |

30.5 |

32.7 |

56.2 |

72.9 |

61.5 |

57.7 |

69.4 |

68.0 |

70.0 |

|

Exchange rate (RUB/$) annual average |

27.2 |

25.6 |

24.9 |

31.7 |

30.4 |

29.4 |

31.0 |

31.9 |

38.6 |

61.4 |

67.0 |

58.3 |

62.8 |

66.3 |

68.5 |

|

Exchange rate (RUB/EUR) year-end |

34.7 |

35.9 |

42.7 |

43.3 |

40.8 |

41.7 |

40.3 |

44.9 |

68.4 |

79.6 |

64.7 |

69.3 |

79.5 |

81.6 |

86.8 |

|

Exchange rate (RUB/EUR) annual average |

34.1 |

35.0 |

36.5 |

44.1 |

40.3 |

40.9 |

39.9 |

42.4 |

50.9 |

68.1 |

74.1 |

65.9 |

74.0 |

78.2 |

83.6 |

Source: Rosstat, CBR, Finance Ministry, Federal Treasury, Bloomberg, IMF, World Bank, Renaissance Capital estimates

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

4 |

|

vk.com/id446425943

Davos edition 2019

Research

Institute

AI & The Future of Work

Thought leadership from Credit Suisse Research and the world's foremost experts

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Introduction

Big data and advances in computing power have triggered a technological revolution that have enormous bearing on the workplace and the labor market. Machines and robots are improving their capacities rapidly through artificial intelligence (AI) and innovations in design and structure. But how this digital revolution will affect firms, workers and their livelihoods is yet to be better understood.

Headline-grabbing assessments of the future of work predict polarizations and an increasing

number of individuals in good and bad jobs, while hollowing out the middle class. Trends since the

1970s confirm this specter of polarization in the USA and the UK, but so far not in continental European countries. However, while the future transformation will be profound, it may be relatively slow, leaving time for many workers

to adapt to the changes in the demand for labor.

There is an inherent difficulty for established companies to truly unleash the full potential of AI as their core strategy. It may now be time for management to think beyond the process of innovation, and also consider alternative budgeting approaches and capital structures to fuel the critical work surrounding AI.

Platforms that facilitate the exchange of goods and services are fostering an ever-growing gig economy, an employment concept in which people are paid for each specific short-term task. The most important challenge is to ensure that incomes are predictable and high enough to ensure a reasonable quality of life. However, too much regulation of freelance work could result in the curtailing or even demise of the gig economy.

While AI promises substantial advances in productivity, it should not threaten or violate human dignity. Accordingly, the legal and ethical challenges of free entrepreneurship and the need to gather vast amounts of data to develop AI are discussed in the final section of this report.

We hope that our findings will prove valuable and

I wish you a most insightful and enjoyable read.

Urs Rohner

Chairman of the Board of Directors

Credit Suisse Group AG

2

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

02 Introduction

05

What technological change means for the future of work

Rafael Lalive

Daniel Oesch

11

How to make AI transformation more likely to succeed

Howard Yu

Jialu Shan

21

Economic security in the gig economy

Giuliano Bonoli

27

AI: Legal and ethical challenges

Bettina Hummer

31 References

34

About the authors

36

General disclaimer / important information

CREDIT SUISSE AG

Research Institute Paradeplatz 8 CH-8070 Zurich Switzerland

research.institute@credit-suisse.com credit-suisse.com/researchinstitute

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

AI & The Future of Work |

3 |

|

|

vk.com/id446425943

4

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943What technological change means for the future of work

Rafael Lalive and Daniel Oesch

University of Lausanne

Big data and advances in computing power have triggered a technological revolution that may have enormous bearing on the workplace and the labor market. Machines and robots are improving their capacities rapidly through artificial intelligence (AI) and innovations in design and structure. Digital assistants organize schedules, plan trips, and provide answers

to many questions people have. Autonomous cars drive around on our streets and can bring customers from the pick-up point to any place they desire.

These developments in technology are exciting, and bring enormous improvements, especially for consumers and entrepreneurs, but they also fuel fears that expanding artificial intelligence and machine capabilities may make humans obsolete in the production process. Our objective is to discuss how and why these fears come about, whether they were true in the recent past, and to what extent they will apply in the near future. Specifically, we first sketch a framework that allows us to discuss the effects of machines on employment. This framework is an abstraction of the real world, but is useful to assess how machines affect employment.

Second, we review how technology has affected employment in the recent past. Third, we discuss what the future of work could look like.

Analytical framework

We adopt a framework developed by Acemoglu and Autor (2011) on task allocation to discuss how technology affects employment. The framework starts with the premise that firms employ workers to fulfill tasks. A task is a unit of work that is directly needed in production. Tasks differ in terms of complexity. Workers supply effort to perform tasks and differ in terms of their skills, where “skill” refers to the capability to perform tasks. Simple tasks can be performed easily by skilled and unskilled workers, but complex tasks

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

can only be performed easily by skilled workers. Workers earn wages that are in line with their skills. In this context, firms will allocate tasks in a very intuitive fashion. The low-skilled workers perform the least complex tasks because their comparative advantage, the ratio of output to cost, is highest in these tasks. The high-skilled workers will perform the most complex tasks, and intermediate-skilled workers perform the skills of intermediate complexity. Workers perform the tasks that correspond to their level of skill.

Technology in the form of machines, robots or digital assistants competes with humans for tasks. Machines in factories and computers in workplaces have taken on the repetitive, but cognitively demanding work of, for instance, office clerks (automatic teller machines). Fewer workers with intermediate skills are needed to execute tasks of intermediate complexity, and these workers then compete with both lowskilled and high-skilled workers for lowand high-complexity tasks. Intermediate-level jobs will fare less well, with lower employment and lower wages. According to this line of reasoning, technology has led to a hollowing out of the middle class, a phenomenon called polarization. However, technology may also have been used to replace workers of low complexity. In this case, employment in highly-paid jobs grows

AI & The Future of Work |

5 |

vk.com/id446425943

strongest, and lower-paid jobs disappear, a phenomenon called educational upgrading. The framework identifies the primary drivers of the employment effects of technology, but only empirical analysis can tell which of the two scenarios, polarization or upgrading, is more relevant.

Machines and employment in the recent past

The view that the labor markets are polarizing has become widely accepted in economics

(Autor and Dorn 2013, Goos et al. 2014). So far, the empirical evidence for job polarization is largely limited to the USA and the UK (Wright and Dwyer 2003, Goos and Manning 2007, Autor and Dorn 2013). In contrast, most studies for Western Europe point toward the upgrading of the occupational structure (Fernandez-Macias 2012, Oesch 2013, Fernandez-Macias and Hurley 2016), which is particularly true for Switzerland (Murphy and Oesch 2018).

We assess whether polarization or upgrading is relevant for four large European economies,

Germany, Spain, Sweden and the UK. Changes in the employment structure can be empirically

analyzed by adopting the analytical strategy of job-quality quintiles (Wright and Dwyer 2003).

Its building blocks are occupations that are rankordered on the basis of their median earnings. These rank-ordered occupations are then grouped into five job-quality quintiles, with quintile 1 comprising the least-paid – and thus least-skilled – occupations and quintile 5 comprising the best-paid – and thus most advantageous – occupations. Each quintile comprised 20% of total employment at the beginning of the period under study, i.e. the early 1990s.

This allows us to calculate occupational change up to 2015 by tracing employment changes in each of the five quintiles.

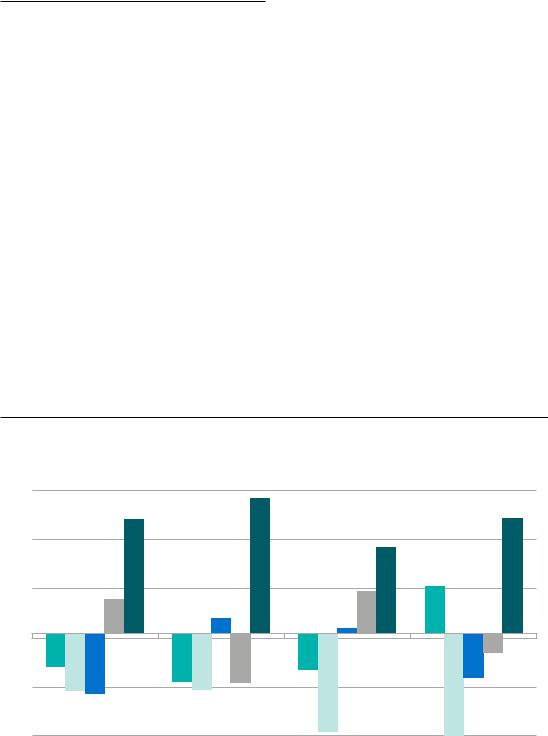

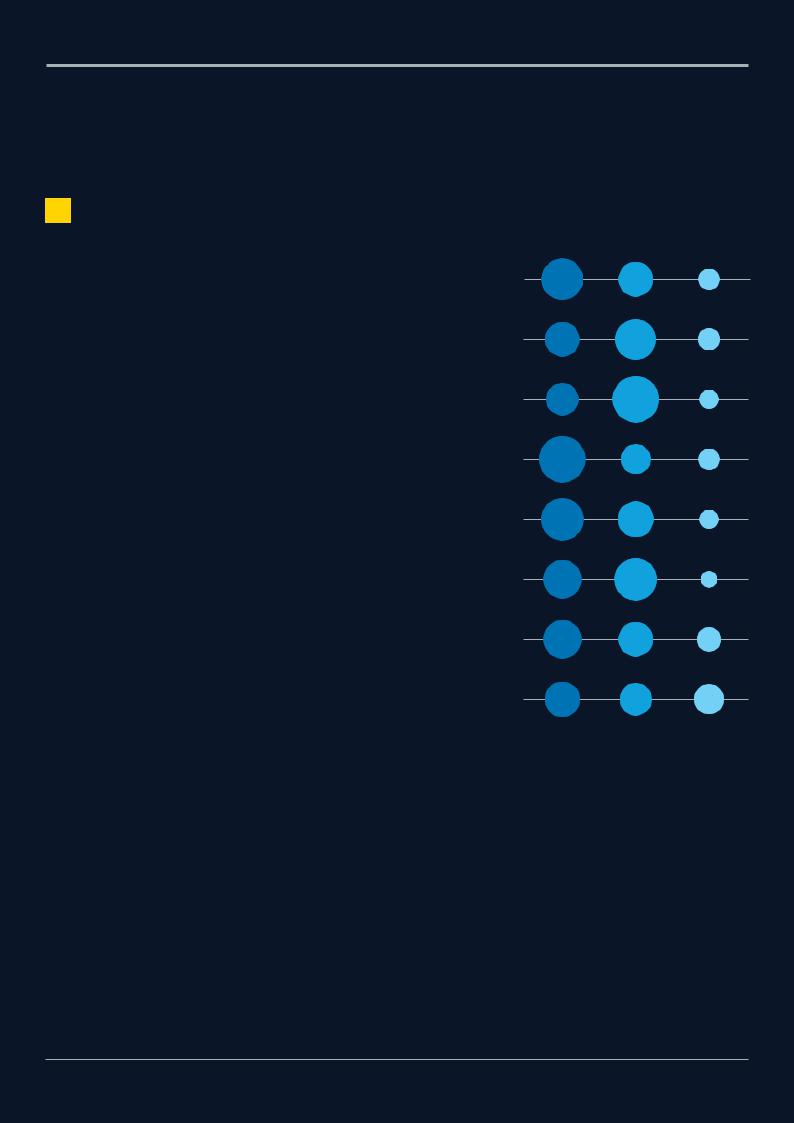

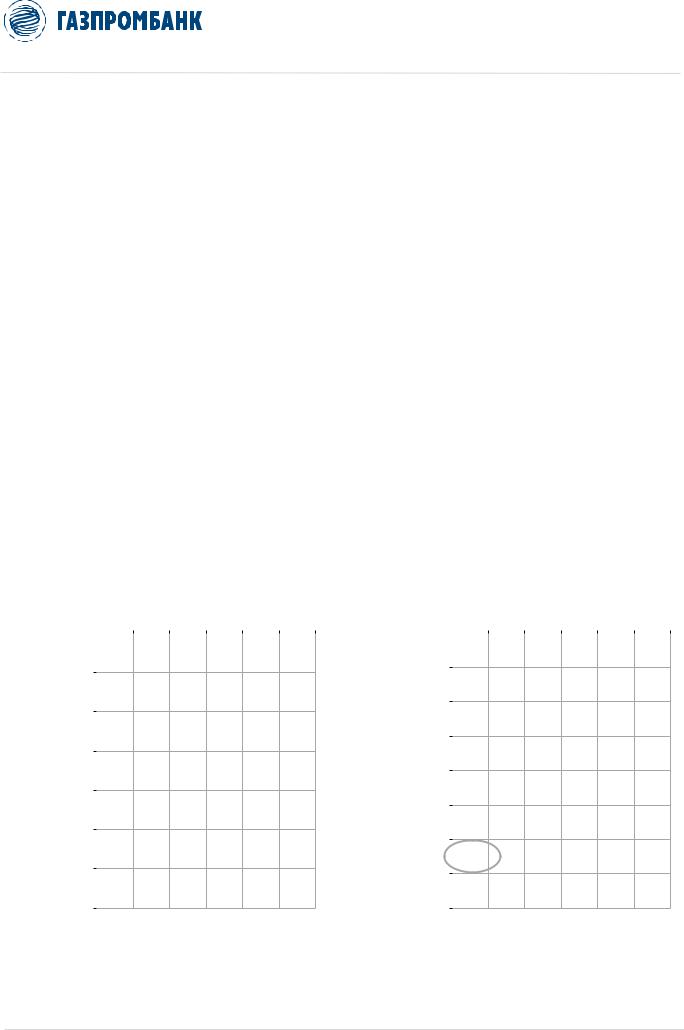

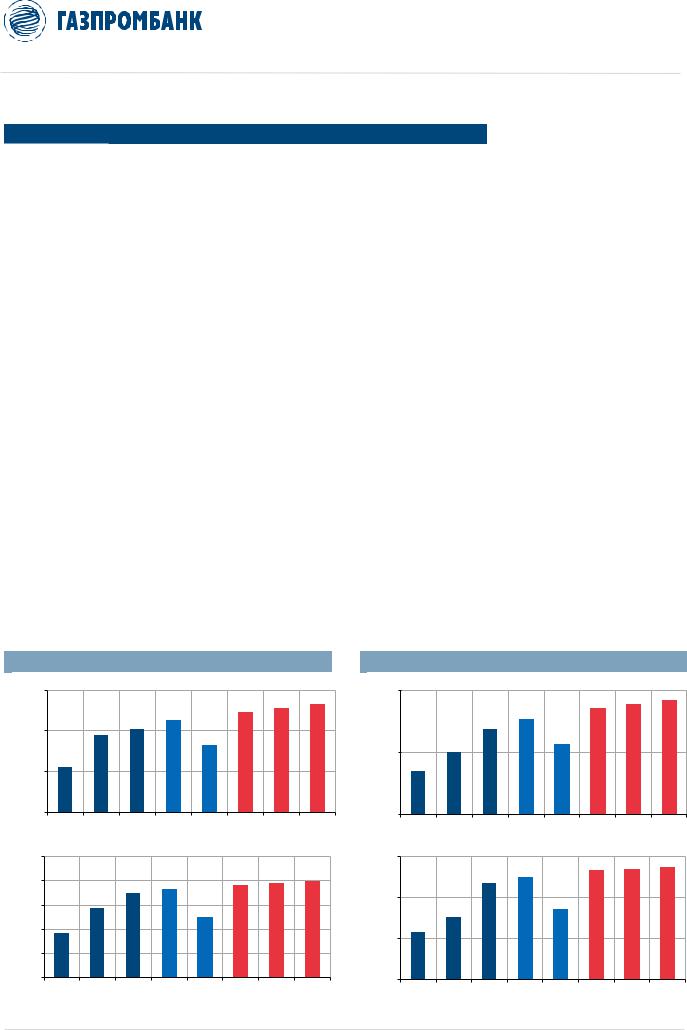

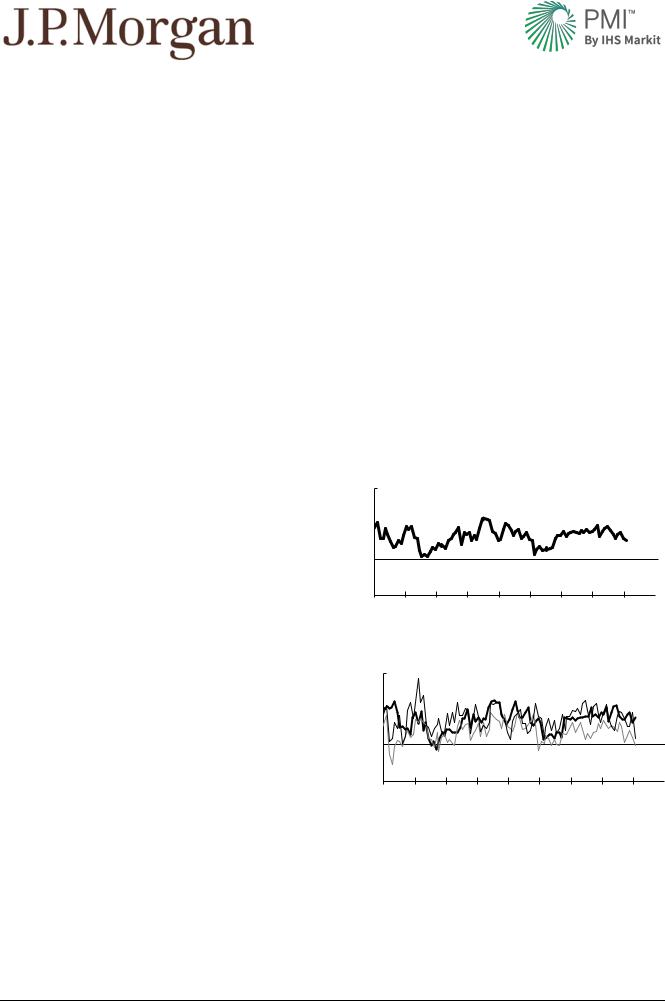

Figure 1 shows the pattern of occupational change for Germany, Spain, Sweden and the

UK over the last two decades. In each one of these four European countries, employment expanded most strongly in the top quintile and either fell or stagnated in the three lowest

job-quality quintiles. The pattern of occupational upgrading is clear-cut in Germany, Sweden and Spain, whereas it has a polarizing thrust in the UK, where employment also increased in the least-paid occupations.

Figure 1: Relative change in employment across job-quality quintiles 1992–2015

In percentage points

15

10

5

0

-5

-10

|

Germany |

|

|

Spain |

|

|

Sweden |

UK |

|||

|

Quintile 1 (bottom) |

|

Q2 |

|

|

Q3 |

|

Q4 |

|

Quintile 5 (top) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

Data: EU-LFS (Labor Force Survey) 1992–2015 for Germany, Spain and the UK, 1997–2015 for Sweden.

Reading example: in Germany 1992–2015, the share of total employment set in the lowest-paid occupations of quintile 1 fell by 3.3 percentage points, whereas it increased by 11.7 percentage points in the highest-paid occupations of quintile 5.

Source: Oesch and Piccitto (forthcoming).

6

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Over the last three decades, European economies have been most successful in the automation and offshoring of low-paid, low-skilled and low-status occupations such as farm workers and plant operators, data-entry clerks and sales assistants. In parallel, job expansion was most vigorous among higher-paid and better-skilled positions in management and the professions (Oesch 2013).

As a result, labor-market opportunities expanded for the salaried (upper) middle class, whereas the core of the traditional working class and subordinate white-collar employees lost ground.

For the polarization thesis to hold, we should also have observed job growth in low-skilled services among interpersonal service workers. However, this mostly female class did not substantially increase its employment share in Western Europe

(Oesch and Piccitto, forthcoming).

While the doom scenario of polarization and middle-class erosion may make newspaper headlines, it is not in line with the secular trends in Western Europe’s employment structure. Given the extent of educational expansion over the last few decades, this is good news. As technical colleges and universities were sending out highly educated workers in greater numbers, the economy was also creating more jobs in occupations requiring higher education. However, it is an altogether different question whether upgrading trends from the past translate into the future.

Disruption versus continuous change

Adopting the framework we sketched out earlier, Frey and Osborne (2017) questioned a group of machine learning experts and examined job descriptions to identify computerization bottleneck tasks that would preclude an occupation from being computerized. They estimated the share of jobs that are exposed to automation to account for 47% of total employment in the USA.

However, other scholars present very different assessments of how technology will affect the labor market of the future. Two recent OECD studies expect that 9%–14% of all jobs could be easily automated in the near future (Arntz et al. 2016, Nedelkovska and Quintini 2018). Since the OECD studies focus on individual tasks rather than entire occupations, the estimates therefore diverge widely and are very sensitive to assumptions. They point to two very distinct future scenarios: a first scenario predicts a deep break with sudden and disruptive changes, while a second scenario holds continuous and progressive change as more likely.

Automation and employment: The scenario of disruptive change

According to the scenario of disruptive change, the next wave of automation should replace employment in a wide range of activities, including agriculture, industrial production and logistics (through robotization), ground transportation (through unmanned machinery), secretarial and administrative support (through new software and Big Data), sales (through self-checkout), cleaning (through robots) and even construction (through prefabrication).

Most studies suggest that the degree of automation is negatively correlated with the level of training in a given profession. Low-skilled occupations would therefore be more exposed to technological change than occupations requiring a high level of training. More specifically for Switzerland, a recent analysis suggests that vocational education and training (VET) graduates are more threatened by automation than university graduates. While 65% of the jobs held by the former would be threatened, this is only the case for 25% of the jobs held by academics.

The disruption scenario predicts de-industrial- ization and therefore a decreasing demand for production workers employed in manufacturing.

Through its impact on the secretariat, payment management, IT maintenance and e-com- merce, digitalization would also jeopardize the jobs of commercial employees, sales assistants and retail managers. More generally, structural changes in the labor market should mainly affect the weakest areas – both in terms of educational level and geographical setting, with the peripheral regions of countries being more affected than the service centers of large cities.

Automation and employment:

The scenario of continuous change

The second scenario predicts a much more gradual change. Widespread automation will not take years, but decades in the second scenario – and will depend on various factors such as the feasibility and costs of new technological solutions as well as their legal, social and political acceptance.

The technical feasibility of automating a process does not necessarily mean that an activity will be automated and employment will disappear any time soon. Moreover, workers continuously adapt to technological change and the multiple tasks that make up an occupation will constantly evolve over time.

Some tasks appear difficult to automate, especially if they involve social skills (negotiating, coordinating, teaching or care-giving) or creative skills (inventing new products and services, creating art and culture). Therefore, automation does not seem to threaten the bulk of employment in areas such as management,

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

AI & The Future of Work |

7 |

|

|

vk.com/id446425943

engineering, science, education, medicine, culture or the police. New product innovation will create new tasks, and new tasks are typically given to workers who explore and develop them before they are encoded and entrusted to a machine.

New technologies will certainly lead to a decrease in jobs in some occupations and industries. Yet, at the same time, they will also generate many new jobs. By way of illustration, it can be noted that, despite strong technological progress, more than 860,000 net jobs have been created in

Switzerland over the last two decades. The

Federal Council (2017) therefore expects the adoption of digital technology, as with previous technological innovations, to contribute to job growth in Switzerland. While studies are abundant on jobs that are lost through automation, it is very difficult to estimate the number of new jobs that will be created as a result of the digital shift.

Overall, this second scenario is therefore much more optimistic. However, it does not deny that there is a need to continually adapt the population’s skills.

Which jobs in the future?

Using the second step-by-step scenario as a starting point, the employment evolution can be projected for different occupational groups using two sources. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics provides projections for employment trends between 2016 and 2026. These projections do not share the alarmism of the disruptive scenario.

On the contrary, it forecasts an increase in total employment of 7% between 2016 and 2026.

For five occupational groups, growth is expected to be much higher. The most spectacular surge is predicted for workers in health care (+24%) and personal services (+15%), particularly among home helpers, care givers and medical assistants. Two other major groups that are also expected to grow strongly are health specialists, including therapists and nurses (+15%) and computer and mathematical experts (+15%).

The largest decline is projected in the USA for production occupations (–4%), particularly among metal and mechanical engineering

workers. Employment is expected to stagnate in the agricultural trades as well as in administrative support jobs, commonly associated with the back office (0%). A third intermediate group includes occupations that are expected to grow at the same rate as the overall labor market, such as jobs in construction, catering, management and education.

A plausibility test consists of comparing these projections with the indicators that assess the current employment demand for skilled labor in

Switzerland (shortage indicators). As structural

changes in the labor market are slow, these indicators should provide us with information on the evolution of the labor market in the coming years. Shortage indicators also suggest that labor demand will remain particularly vigorous in health, where many jobs have been created over the last fifteen years (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs [SECO] 2016). It is likely that demographic aging will continue to stimulate demand for manpower in an area where the potential for automation seems limited. In

Switzerland, however, it is mainly the highly qualified professions – such as doctors or pharmacists – that are showing signs of shortage, while this is less the case for, say, dental assistants or pharmacy assistants. Switzerland also has a shortage in the so-called “MINT” professions (mathematics/information technology/natural sciences/technology) among engineers and computer scientists, as well as among specialists in management, law and education. Finally, there are no visible shortages in agriculture, the food industry, textiles, catering, commercial and administrative professions or cleaning. In

general, occupations showing the most signs of shortages have training requirements that are significantly higher than average, while the opposite is true for occupations with no shortages

(SECO 2016).

New technologies will certainly lead to a decrease in jobs in

some occupations and industries. Yet, at the same time, they will also generate many new jobs.

Technology will affect how firms recruit workers. In many markets, many workers want the same job, and many employers want the same worker.

This situation generates the problem of congested labor markets. All workers apply to the same firm, all employers invite the same candidate, and both workers and firms need to wait until the market clears. Digital platforms can use information about the preferences of workers and firms, a bit like the online dating app Tinder does

8

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

in the context of matching partners. Additional information will help speed up the matching process, especially if the market provides workers and firms with information on the feasibility of matches. More information can also lead to more inequality because information helps workers and firms pair up exactly, while currently luck is an important element of forming an employment relationship.

Conclusion

Are we heading toward a future where computers, robots and AI replace human labor and lead to mass unemployment? Warnings about a future of widespread technological unemployment are as old as the industrial revolution. They have been periodically voiced, most prominently by Jeremy Rifkin in 1992 with his book “The End of Work.” When Rifkin made his prophecy of a jobless future, the USA had a civilian labor force of 118 million people. In

2018, civilian employment increased to 155 million people – a figure that becomes truly astounding when compared to the 29 million gainfully employed workers in 1900 – among whom 40% were still employed in agriculture. Despite the huge labor-saving potential of combustion engines, assembly lines, nuclear power and micro-chips, many more people are working today in the USA than 120 years ago

– and the USA is not alone. Between 1950 and 2015, the total volume of work performed in Switzerland grew from 5.5 billion to 7.8 billion working hours (Siegenthaler 2017).

How can labor-saving technology be introduced without leading to the end of work? Computers and robots will only be used where they lead to productivity gains and, consequently, additional income. These productivity gains can benefit three groups of stakeholders: (1) the workforce whose productivity has increased in the form of wage increases; (2) business owners who benefit from an increase in their profits; or

(3) consumers who benefit from lower prices. In practice, productivity gains tend to benefit all three groups to some extent. These three groups will then use their increased income to acquire more goods and services, which should in turn lead to employment growth.

Hence our argument would be that there is no shortage of work to be done in contemporary economies. Rather, there is a lack of financial means to pay for all the work that would be socially desirable. It suffices to think of the development and maintenance of public infrastructure (public transport), healthcare (care of the elderly) or education (affordable quality pre-schools).

Rather than a jobless economy, the two great challenges in the labor market may then be massive dislocation on the one hand and the distribution of productivity gains on the other. While technological change will not lead to the end of work, it will certainly displace people from occupations and sectors. In this context, broad access to initial and further education will become increasingly important for people’s life chances. Likewise, popular support for technological progress may grow weak and weaker if the resulting productivity gains continue to be pocketed by a small elite of winners – rather than be shared widely across the workforce as was the case during the post-war decades.

Western societies benefited in the post-war decades from an institutional framework that responded well to the technological challenge created by Fordist mass production: the Keynesian class compromised with full-employment policies, strong unions and the development of the welfare state. The

democratic challenge of the next decades will be to develop a new institutional framework that allows modern societies to fully harness – and broadly share – the potential of the digital revolution.

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

AI & The Future of Work |

9 |

|

|

vk.com/id446425943

10

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943How to make AI transformation more likely to succeed

Howard Yu and Jialu Shan

IMD

To get the most out of artificial intelligence (AI), companies need more than just data, infrastructure, and off the-shelf analytics; they need to redesign their investment processes. In this chapter, we examine the inherent difficulty for established companies to truly unleash the full potential of AI as their core strategy. We conclude that senior executives must think beyond the process of innovation as well as consider an alternative budgeting approach and capital structure to fuel the critical work surrounding AI.

What are we learning about artificial intelligence in financial services?” asked Ms. Lael Brainard, one of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve. “My focus today is the branch of artificial intelligence known as machine learning, which is the basis of many recent advances and commercial applications,” the governor told her audience in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania. “Due to an early commitment to open-source principles, AI algorithms from some of the largest companies are available to even nascent start-ups... So it is no surprise that many financial services firms are devoting so much money, attention, and time to developing and using AI approaches.”

JPMorgan Chase is reportedly devoting some USD 10.8 billion to its tech budget in 2018.

Europe’s largest bank, HSBC, is spending USD

15 billion on new technology. And the biggest spender of all, Bank of America, has set an annual global budget of nearly USD 16 billion for technology and operations. That figure is at least USD 3 billion more than Intel, Microsoft or Apple spent on research and development in

2018. As Andrew S. Grove, the long-time chief executive and chairman of Intel Corporation, told a Stanford researcher in 1991, “Don’t ask managers, ‘What is your strategy?’ Look at what they do!

Because people will pretend.” Whether they are pretending or not, the resource allocation patterns suggest that banks are now effectively IT companies.

What Grove saw as the actual strategy of a firm is the cumulative effect of day-to-day prioritizations or decisions made by middle managers, engineers, salespeople, and financial staff – decisions that are made despite, or in the absence of, intentions. And that

is where the problem lies. Money for new investments accounted for only 27% of bank spending on information technology in 2017.

According to Celent, a research and consulting company based in Boston, the rest – close to 73% of spending – was allocated to system maintenance. Of the nearly USD 10 billion JPMorgan Chase spent on IT in 2016, only USD 600 million was in fact devoted to fintech solutions and projects for mobile or online banking, although CEO Jamie Dimon warned shareholders in his letter that “Silicon

Valley is coming.”

This knowing-doing gap is no simple pretension by senior leadership. Financial institutes we have spoken with have (1) all organized employee seminars inviting motivational speakers to talk about innovation; (2) established corporate venture funds to invest in innovative startups;

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts |

AI & The Future of Work |

11 |

|

|

vk.com/id446425943

(3) practiced open innovation, posted challenges online, and run tournaments with external inventors; (4) organized “design thinking” workshops for employees to re-think customer solutions outside the mainstream; and (5) installed Lean Startup methodologies that allow employees to fail fast

in order to succeed early. So widespread is the innovation process, and yet, managers continue to face unyielding organizations whose core business is being encroached on by Google and

Amazon, if not Tencent or Alibaba or some other digital upstarts. “Tell me one thing that I should do but haven’t done,” hissed an executive the moment we mentioned Google Venture. It seems that no matter how hard these in-house innovation experts try, their companies simply will not budge.

The ships are not just big; they cannot turn. Why?

Seizing a window of opportunity is not necessarily about being the first, but

about getting it right first.

Too many innovation experts are focusing solely on the nuts and bolts of everyday implementation: gathering data, tweaking formulas, iterating algorithms in experiments and different combinations, prototyping products, and experimenting with business models. They often forget that the underlying technologies – AI in this case – never stay constant. Seizing a window of opportunity is not necessarily about being the first, but about getting it right first. In this instance, that means getting it right for banking clients. Doing so takes courage and determination, as well as vast resources and deep talent. But the banking industry is not where

Silicon Valley comes first – the auto industry is.

How likely is it that your industry will be disrupted by the Valley?

No automaker today would speak to investors without mentioning “future mobility.” BMW is “a supplier of individual premium mobility with

innovative mobility services.” General Motors aims to “deliver on its vision of an all-electric, emis- sions-free future.” Toyota possesses the “passion to lead the way to the future of mobility and an enhanced, integrated lifestyle.” And Daimler,

maker of Mercedes, sees the future as “connected, autonomous, and smart.” In contrast to the personally owned, gasoline-powered, human-driven vehicles that dominated the last century, automakers know they are transitioning to mobility services based on driverless electric vehicles paid for by the trip, by the mile, by monthly subscription, or a combination of all three. In the past, mobility was created by individual cars automakers sold; in the future, mobility will be produced by service companies operating various kinds of self-driving vehicles in fleets over time. At the

BMW Museum, anyone can witness the gravity of this vision first-hand, articulated by its chairman of the board.

Walking up the spiral ramp of a rotunda inside the BMW Museum, one sees flashes of pictures about BMW history that display in variable sequences, slipping in and out of view like mirages. At the very top of the museum is a “themed area” of about 30 stations demon-

strating an emissions-free, autonomously driven future. These are not only a vision, but a real project, begun in earnest in the autumn of 2007 by then-CEO Norbert Reithofer and his chief strategist Friedrich Eichiner. The two men tasked engineer Ulrich Kranz, who had revived the Mini brand in 2001, to “rethink mobility.”

The task force soon grew to 30 members and moved into a garage-like factory hall inside BMW’s main complex.

“I had the freedom to assemble a team the way I wanted. The project was not tied to one of the company’s brands, so it could tackle any problem,” Kranz said in an interview with Automotive News Europe in 2013. “The job was to position

BMW for the future—and that was in all fields: from materials to production, from technologies to new vehicle architectures.” And so Kranz and his team decided to explore uncharted territory that included “the development of sustainable mobility concepts, new sales channels, and marketing concepts, along with acquiring new customers.” The starting point for “Project i” was, in other words, a blank sheet of paper.

“We traveled to a total of 20 megacities, including Los Angeles, Mexico City, London, Tokyo, and Shanghai. We met people who live in metropolises and who indicated that they had a sustainable lifestyle. We lived with them, traveled with them to work, and asked questions,” Kranz recalled. “We wanted to know the products that they would like from a car manufacturer, how their commute to work could be improved, and how they imagined their mobility in the future. As a second step, we asked the mayors and city planners in each metropolis about their infrastructure problems, the regulations for internal combustion engines, and the advantages of electric vehicles.”

12

http://new.guap.ru/i04/contacts

vk.com/id446425943

Once the findings came back, Kranz expanded his team by seeking out “the right employees both internally and externally.” The result was BMW’s gas-electric i8 sports coupe and all-electric i3 people mover, which shimmered under white lights at BMW World, where

the company’s top automotive offerings are showcased. The i3 had almost no hood, and the front grille was framed by plastic slits that looked like a pair of Ray-Bans. It came in a fun-looking burnt orange. The front seats were so vertically poised, with the dashboard stretching out, that they exuded a “loft on wheels” vibe. Like the interior, made of recycled carbon fiber and faux-wood paneling, the electric motor of the i3 was geared to urban dwellers in megacities who yearned for a calm, relaxing drive.

What made BMW all the more remarkable was its timing. Almost two years before Tesla’s

Model S was introduced, BMW had presented the battery-powered car as a revolutionary product, and committed to build it and deliver it to showrooms by 2013. When the BMW i3 went on sale, Tesla’s Model S had spent just over a year on the US market. The 2014 i3 went on to win a World Green Car award, as did the 2015 model, the i8. In short, BMW was fast and early.

Then something terrible happened – or really nothing happened.

The i3 is now five years old, and the i8 is four.

The BMW i brand includes the services Drive-