Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Dermatitis. With contact dermatitis, a hypersensitivity reaction produces an eruption of small vesicles surrounded by redness and marked edema. The vesicles may ooze, scale, and cause severe pruritus.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a skin disease that’s most common in men between ages 20 and 50 (and is occasionally associated with celiac disease, organ malignancy, or immunoglobulin A immunotherapy) and produces a chronic inflammatory eruption marked by vesicular, papular, bullous, pustular, or erythematous lesions. Usually, the rash is symmetrically distributed on the buttocks, shoulders, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and sometimes the face, scalp, and neck. Other symptoms include severe pruritus, burning, and stinging.

With nummular dermatitis, groups of pinpoint vesicles and papules appear on erythematous or pustular lesions that are nummular (coinlike) or annular (ringlike). Often, the pustular lesions ooze a purulent exudate, itch severely, and rapidly become crusted and scaly. Two or three lesions may develop on the hands, but the lesions typically develop on the extensor surfaces of the limbs and on the buttocks and posterior trunk.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute inflammatory skin disease that’s heralded by a sudden eruption of erythematous macules, papules and, occasionally, vesicles and bullae. The characteristic rash appears symmetrically over the hands, arms, feet, legs, face, and neck and tends to reappear. Although vesicles and bullae may also erupt on the eyes and genitalia, vesiculobullous lesions usually appear on the mucous membranes — especially the lips and buccal mucosa — where they rupture and ulcerate, producing a thick, yellow or white exudate. Bloody, painful crusts, a foul-smelling oral discharge, and difficulty chewing may develop. Lymphadenopathy may also occur.

Herpes simplex. Herpes simplex is a common viral infection that produces groups of vesicles on an inflamed base, most commonly on the lips and lower face. In about 25% of cases, the genital region is the site of involvement. Vesicles are preceded by itching, tingling, burning, or pain; develop singly or in groups;, are 2 to 3 mm in size; and do not coalesce. Eventually, they rupture, forming a painful ulcer followed by a yellowish crust.

Herpes zoster. With herpes zoster, a vesicular rash is preceded by erythema and, occasionally, by a nodular skin eruption and unilateral, sharp, pain along a dermatome. About 5 days later, the lesions erupt and the pain becomes burning. Vesicles dry and scab about 10 days after eruption. Associated findings include fever, malaise, pruritus, and paresthesia or hyperesthesia of the involved area. Herpes zoster involving the cranial nerves produces facial palsy, hearing loss, dizziness, loss of taste, eye pain, and impaired vision.

Insect bites. With insect bites, vesicles appear on red hivelike papules and may become hemorrhagic.

Pemphigoid (bullous). Generalized pruritus or an urticarial or eczematous eruption may precede pemphigoid — a classic bullous rash. Bullae are large, thick walled, tense, and irregular, typically forming on an erythematous base. They usually appear on the arms, legs, trunk, mouth, or other mucous membranes.

Pompholyx (dyshidrosis or dyshidrosis eczema). Pompholyx is a common, recurrent disorder that produces symmetrical vesicular lesions that can become pustular. The pruritic lesions are more common on the palms than on the soles and may be accompanied by minimal erythema.

Porphyria cutanea tarda. Bullae — especially on areas exposed to sun, friction, trauma, or heat

— result from abnormal porphyrin metabolism. Photosensitivity is also a common sign. Papulovesicular lesions evolving into erosions or ulcers and scars may appear. Chronic skin

changes include hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, hypertrichosis, and sclerodermoid lesions. Urine is pink to brown.

Scabies. Small vesicles erupt on an erythematous base and may be at the end of a threadlike burrow. Burrows are a few millimeters long, with a swollen nodule or red papule that contains the mite. Pustules and excoriations may also occur. Men may develop burrows on the glans, shaft, and scrotum; women may develop burrows on the nipples. Both sexes may develop burrows on the webs of the fingers, wrists, elbows, axillae, and waistline. Associated pruritus worsens with inactivity and warmth and at night.

Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include high fever, malaise, prostration, severe headache, backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust. Later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

Tinea pedis. Tinea pedis is a fungal infection that causes vesicles and scaling between the toes and, possibly, scaling over the entire sole. Severe infection causes inflammation, pruritus, and difficulty walking.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is an immune reaction to drugs or other toxins, in which vesicles and bullae are preceded by a diffuse, erythematous rash and followed by large-scale epidermal necrolysis and desquamation. Large, flaccid bullae develop after mucous membrane inflammation, a burning sensation in the conjunctivae, malaise, fever, and generalized skin tenderness. The bullae rupture easily, exposing extensive areas of denuded skin. (See Drugs That Cause Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis.)

Special Considerations

Any skin eruption that covers a large area may cause substantial fluid loss through the vesicles, bullae, or other weeping lesions. If necessary, start an I.V. line to replace fluids and electrolytes. Keep the patient’s environment warm and free from drafts, cover him with sheets or blankets as necessary, and take his rectal temperature every 4 hours because increased fluid loss and increased blood flow to inflamed skin may lead to hyperthermia.

Drugs That Cause Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Various drugs can trigger toxic epidermal necrolysis — a rare but potentially fatal immune reaction characterized by a vesicular rash. This type of necrolysis produces large, flaccid bullae that rupture easily, exposing extensive areas of denuded skin. The resulting loss of fluid and electrolytes — along with widespread systemic involvement — can lead to such life-threatening complications as pulmonary edema, shock, renal failure, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Here’s a list of some drugs that can cause toxic epidermal necrolysis:

Allopurinol

Aspirin

Barbiturates

Chloramphenicol

Chlorpropamide

Gold salts

Nitrofurantoin

Penicillin

Phenytoin

Primidone

Sulfonamides

Tetracycline

Obtain cultures to determine the standard causative organism. Use precautions until infection is ruled out. Tell the patient to wash his hands often and not to touch the lesions. Be alert for signs of secondary infection. Give the patient an antibiotic, and apply corticosteroid or antimicrobial ointment to the lesions.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of frequent hand washing and the need to avoid touching the lesions. Instruct the patient to use tepid baths or cold compresses to relieve itching.

Pediatric Pointers

Vesicular rashes in children are caused by staphylococcal infections (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a life-threatening infection occurring in infants), varicella, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, contact dermatitis, and miliaria rubra.

Reference

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Violent Behavior

Marked by sudden loss of self-control, violent behavior refers to the use of physical force to violate, injure, or abuse an object or person. This behavior may also be self-directed. It may result from an organic or psychiatric disorder or from the use of certain drugs.

History and Physical Examination

During your evaluation, determine if the patient has a history of violent behavior. Is he intoxicated or suffering symptoms of alcohol or drug withdrawal? Does he have a history of family violence, including corporal punishment and child or spouse abuse? (See Understanding Family Violence.)

Watch for clues indicating that the patient is losing control and may become violent. Has he

exhibited abrupt behavioral changes? Is he unable to sit still? Increased activity may indicate an attempt to discharge aggression. Does he suddenly cease activity (suggesting the calm before the storm)? Does he make verbal threats or angry gestures? Is he jumpy, extremely tense, or laughing? Such intensifying of emotion may herald loss of control.

If your patient’s violent behavior is a new development, he may have an organic disorder. Obtain a medical history, and perform a physical examination. Watch for a sudden change in his level of consciousness. Disorientation, failure to recall recent events, and display of tics, jerks, tremors, and asterixis all suggest an organic disorder.

Medical Causes

Organic disorders. Disorders resulting from metabolic or neurologic dysfunction can cause violent behavior. Common causes include epilepsy, brain tumor, encephalitis, head injury, endocrine disorders, metabolic disorders (such as uremia and calcium imbalance), and severe physical trauma.

Psychiatric disorders. Violent behavior occurs as a protective mechanism in response to a perceived threat in psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. A similar response may occur in personality disorders, such as antisocial or borderline personality.

Understanding Family Violence

Effectively managing the violent patient requires an understanding of the roots of his behavior. For example, his behavior may be spawned by a family history of corporal punishment or child or spouse abuse. His violent behavior may also be associated with drug or alcohol abuse and fixed family roles that stifle growth and individuality.

CAUSES OF FAMILY VIOLENCE

Social scientists suggest that family violence stems from cultural attitudes fostering violence and from the frustration and stress associated with overcrowded living conditions and poverty. Albert Bandura, a social learning theorist, believes that individuals learn violent behavior by observing and imitating other family members who vent their aggressive feelings through verbal abuse and physical force. (They also learn from television and the movies, especially when the violent hero gains power and recognition.) Members of families with these characteristics may have an increased potential for violent behavior, thus initiating a cycle of violence that passes from generation to generation.

Other Causes

Drugs and alcohol. Violent behavior is an adverse effect of some drugs, such as lidocaine and penicillin G. Alcohol abuse or withdrawal, hallucinogens, amphetamines, and barbiturate withdrawal may also cause violent behavior.

Special Considerations

Violent behavior is most prevalent in emergency departments, critical care units, and crisis and acute psychiatric units. Natural disasters and accidents also increase the potential for violent behavior, so be on guard in these situations.

If your patient becomes violent or potentially violent, your goal is to remain composed and to establish environmental control. First, protect yourself. Remain at a distance from the patient, call for assistance, and don’t overreact. Remain calm, and make sure you have enough personnel for a show of force to subdue or restrain the patient if necessary. Encourage the patient to move to a quiet location — free from noise, activity, and people — to avoid frightening or stimulating him further. Reassure him, explain what’s happening, and tell him that he’s safe.

If the patient makes violent threats, take them seriously, and inform those at whom the threats are directed. If ordered, administer a psychotropic medication.

Remember that your own attitudes can affect your ability to care for a violent patient. If you feel fearful or judgmental, ask another staff member for help.

Patient Counseling

Reassure the patient, explain what’s happening, and tell him that he is safe. After the patient is calm, explain the reason for his violent behavior, if known.

Pediatric Pointers

Adolescents and younger children often make threats resulting from violent dreams or fantasies or unmet needs. Adolescents who exhibit extreme violence can come from families with a history of physical or psychological abuse. These children may display violent behavior toward their peers, siblings, and pets.

Vision Loss

Vision loss — the inability to perceive visual stimuli — can be sudden or gradual and temporary or permanent. The deficit can range from a slight impairment of vision to total blindness. It can result from an ocular, a neurologic, or a systemic disorder or from trauma or the use of certain drugs. The ultimate visual outcome may depend on early, accurate diagnosis and treatment.

History and Physical Examination

Sudden vision loss can signal an ocular emergency. (See Managing Sudden Vision Loss .) Don’t touch the eye if the patient has perforating or penetrating ocular trauma.

If the patient’s vision loss occurred gradually, ask him if the vision loss affects one eye or both and all or only part of the visual field. Is the visual loss transient or persistent? Did the visual loss occur abruptly, or did it develop over hours, days, or weeks? What is the patient’s age? Ask the patient if he has experienced photosensitivity, and ask him about the location, intensity, and duration of any eye pain. You should also obtain an ocular history and a family history of eye problems or systemic diseases that may lead to eye problems, such as hypertension; diabetes mellitus; thyroid, rheumatic, or vascular disease; infections; and cancer.

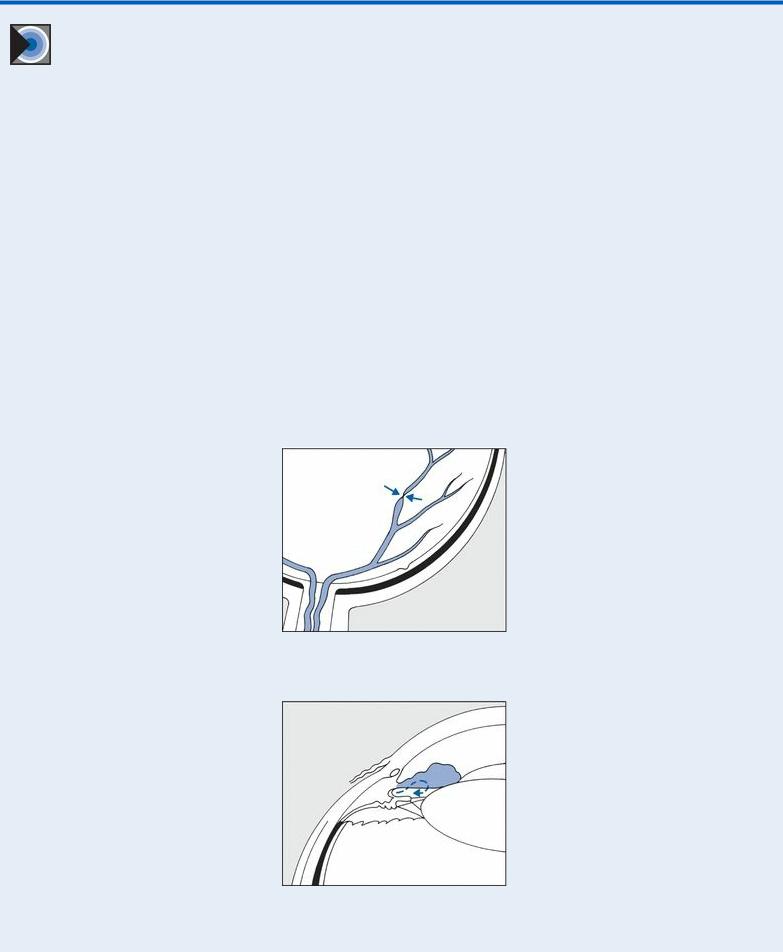

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS Managing Sudden Vision

Loss

Sudden vision loss can signal central retinal artery occlusion or acute angle-closure glaucoma — ocular emergencies that require immediate intervention. If your patient reports sudden vision loss, immediately notify an ophthalmologist for an emergency examination, and perform these interventions:

For a patient with suspected central retinal artery occlusion, perform light massage over his closed eyelid. Increase his carbon dioxide level by administering a set flow of oxygen and carbon dioxide through a Venturi mask, or have the patient rebreathe in a paper bag to retain exhaled carbon dioxide. These steps will dilate the artery and, possibly, restore blood flow to the retina.

For a patient with suspected acute angle-closure glaucoma, measure intraocular pressure (IOP) with a tonometer. (You can also estimate IOP without a tonometer by placing your fingers over the patient’s closed eyelid. A rock-hard eyeball usually indicates increased IOP.) Expect to instill pressure-reducing drops, and administer I.V. acetazolamide to help decrease IOP.

Suspected Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

Suspected Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

The first step in performing the eye examination is to assess visual acuity, with best available correction in each eye. (See Testing Visual Acuity, page 740.)

Carefully inspect both eyes, noting edema, foreign bodies, drainage, or conjunctival or scleral redness. Observe whether lid closure is complete or incomplete, and check for ptosis. Using a flashlight, examine the cornea and iris for scars, irregularities, and foreign bodies. Observe the size, shape, and color of the pupils, and test the direct and consensual light reflex (see Pupils, Nonreactive, pages 613 to 616.) and the effect of accommodation. Evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze. (See Testing Extraocular Muscles, page 240.)

Medical Causes

Amaurosis fugax. With amaurosis fugax, recurrent attacks of unilateral vision loss may last from a few seconds to a few minutes. Vision is normal at other times. Transient unilateral weakness, hypertension, and elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) in the affected eye may also occur.

Cataract. Typically, painless and gradual visual blurring precedes vision loss. As the cataract progresses, the pupil turns milky white.

Concussion. Immediately or shortly after blunt head trauma, vision may be blurred, double, or lost. Generally, vision loss is temporary. Other findings include headache, anterograde and retrograde amnesia, transient loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, irritability, confusion, lethargy, and aphasia.

Diabetic retinopathy. Retinal edema and hemorrhage lead to visual blurring, which may progress to blindness.

Endophthalmitis. Typically, endophthalmitis — an intraocular inflammation — follows penetrating trauma, I.V. drug use, or intraocular surgery, causing possibly permanent unilateral vision loss; a sympathetic inflammation may affect the other eye.

Glaucoma. Glaucoma produces gradual visual field loss that may progress to total blindness. Acute angle-closure glaucoma is an ocular emergency that may produce blindness within 3 to 5 days. Findings are rapid onset of unilateral inflammation and pain, pressure over the eye, moderate pupil dilation, nonreactive pupillary response, a cloudy cornea, reduced visual acuity, photophobia, and perception of blue or red halos around lights. Nausea and vomiting may also occur.

Chronic angle-closure glaucoma has a gradual onset and usually produces no symptoms, although blurred or halo vision may occur. If untreated, it progresses to blindness and extreme pain.

Chronic open-angle glaucoma is usually bilateral, with an insidious onset and a slowly progressive course. It causes peripheral vision loss, aching eyes, halo vision, and reduced visual acuity (especially at night).

Macular degeneration (age related). Occurring in elderly patients, age-related macular degeneration causes painless blurring or loss of central vision. Vision loss may proceed slowly or rapidly, eventually affecting both eyes. Visual acuity may be worse at night.

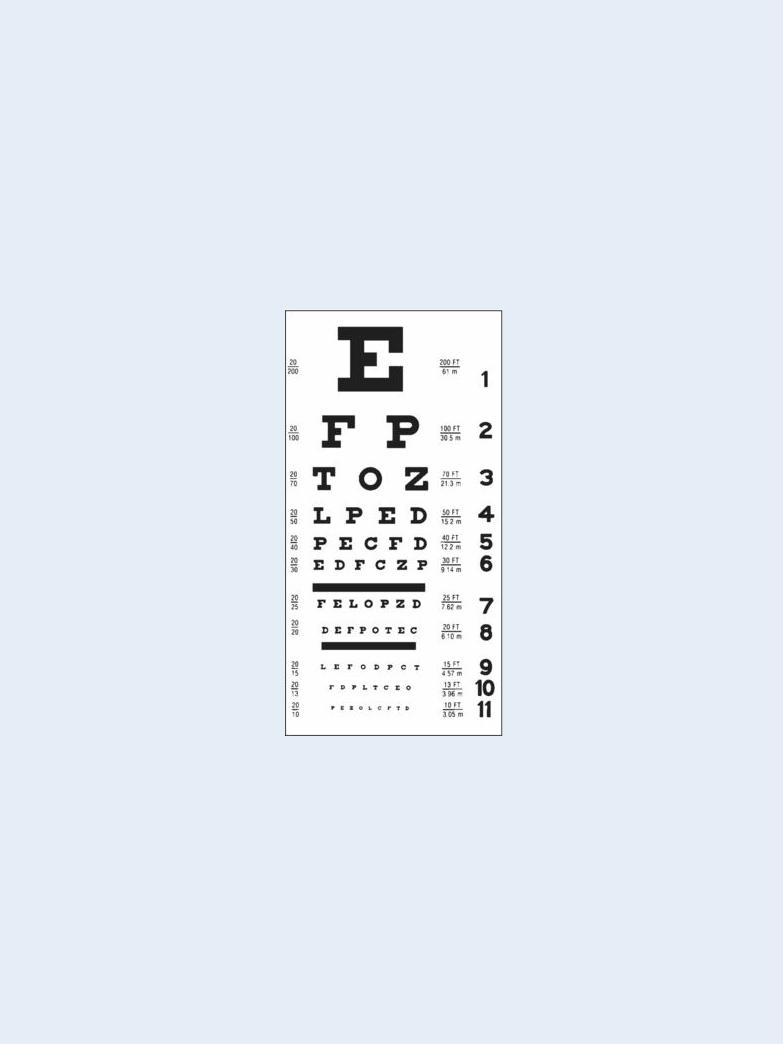

EXAMINATION TIP Testing Visual Acuity

EXAMINATION TIP Testing Visual Acuity

Use a Snellen letter chart to test visual acuity in the literate patient older than age 6. Have the

patient sit or stand 20′ (6 m) from the chart. Then, tell him to cover his left eye and read aloud the smallest line of letters that he can see. Record the fraction assigned to that line on the chart (the numerator indicates distance from the chart; the denominator indicates the distance at which a normal eye can read the chart). Normal vision is 20/20. Repeat the test with the patient’s right eye covered.

If your patient can’t read the largest letter from a distance of 20′ (6 m), have him approach the chart until he can read it. Then, record the distance between him and the chart as the numerator of the fraction. For example, if he can see the top line of the chart at a distance of 3′ (1 m), record the test result as 3/200.

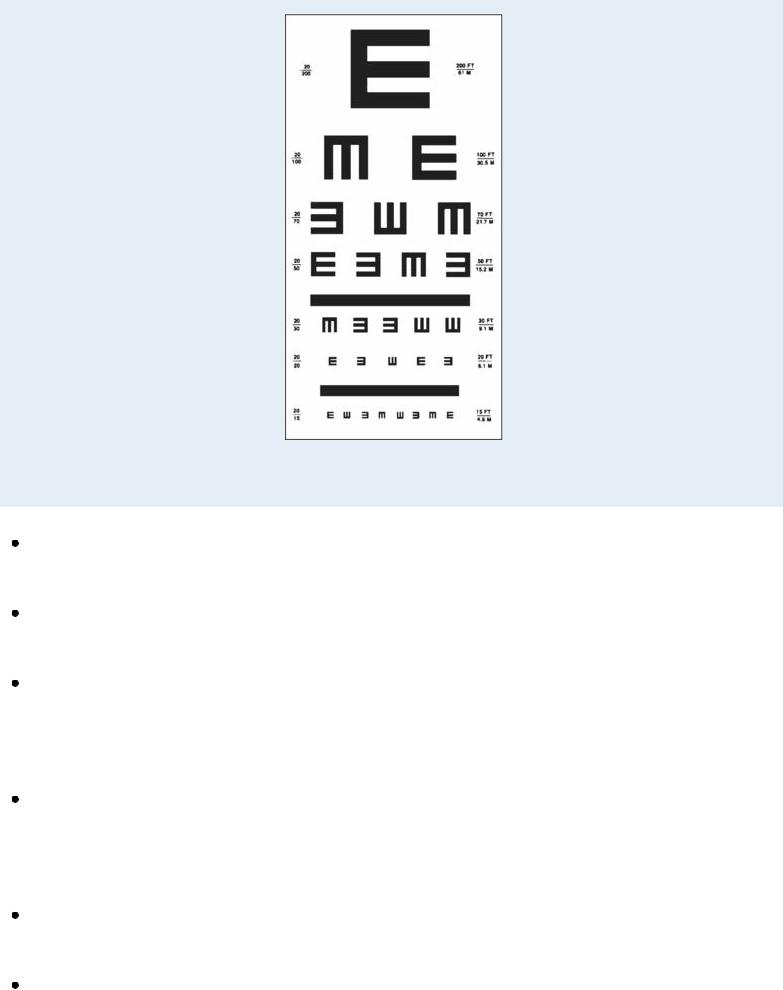

Use a Snellen symbol chart to test children ages 3 to 6 and patients who are illiterate. Follow the same procedure as for the Snellen letter chart, but ask the patient to indicate the direction of the E’s fingers as you point to each symbol.

Snellen Letter Chart

Snellen Symbol Chart

Ocular trauma. Following eye injury, sudden unilateral or bilateral vision loss may occur. Vision loss may be total or partial and permanent or temporary. The eyelids may be reddened, edematous, and lacerated; intraocular contents may be extruded.

Optic atrophy. Degeneration of the optic nerve, optic atrophy can develop spontaneously or follow inflammation or edema of the nerve head, causing irreversible loss of the visual field with changes in color vision. Pupillary reactions are sluggish, and optic disk pallor is evident.

Optic neuritis. An umbrella term for inflammation, degeneration, or demyelinization of the optic nerve, optic neuritis usually produces temporary but severe unilateral vision loss. Pain around the eye occurs, especially with movement of the globe. This may occur with visual field defects and a sluggish pupillary response to light. Ophthalmoscopic examination commonly reveals hyperemia of the optic disk, blurred disk margins, and filling of the physiologic cup.

Paget’s disease. Bilateral vision loss may develop as a result of bony impingements on the cranial nerves. This occurs with hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, and severe, persistent bone pain. Cranial enlargement may be noticeable frontally and occipitally, and headaches may occur. Sites of bone involvement are warm and tender, and impaired mobility and pathologic fractures are common.

Pituitary tumor. As a pituitary adenoma grows, blurred vision progresses to hemianopia and, possibly, unilateral blindness. Double vision, nystagmus, ptosis, limited eye movement, and headaches may also occur.

Retinal artery occlusion (central). Retinal artery occlusion is a painless ocular emergency that causes sudden unilateral vision loss, which may be partial or complete. Pupil examination reveals a sluggish direct pupillary response and a normal consensual response. Permanent

blindness may occur within hours.

Retinal detachment. Depending on the degree and location of detachment, painless vision loss may be gradual or sudden and total or partial. Macular involvement causes total blindness.

With partial vision loss, the patient may describe visual field defects or a shadow or curtain over the visual field as well as visual floaters.

Retinal vein occlusion (central). Most common in geriatric patients, retinal vein occlusion — a painless disorder — causes a unilateral decrease in visual acuity with variable vision loss.

Rift Valley fever. Rift Valley fever is a viral disease that causes inflammation of the retina and may result in some permanent vision loss. Typical signs and symptoms include fever, myalgia, weakness, dizziness, and back pain. A small percentage of patients may develop encephalitis or may progress to hemorrhagic fever that can lead to shock and hemorrhage.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Corneal scarring from associated conjunctival lesions produces marked vision loss. Purulent conjunctivitis, eye pain, and difficulty opening the eyes occur. Additional findings include widespread bullae, fever, malaise, cough, drooling, inability to eat, sore throat, chest pain, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgias, arthralgias, hematuria, and signs of renal failure.

Temporal arteritis. Vision loss and visual blurring with a throbbing, unilateral headache characterize this disorder. Other findings include malaise, anorexia, weight loss, weakness, low-grade fever, generalized muscle aches, and confusion.

Vitreous hemorrhage. With vitreous hemorrhage, sudden unilateral vision loss may result from intraocular trauma, ocular tumors, or systemic disease (especially diabetes, hypertension, sickle cell anemia, or leukemia). Visual floaters and partial vision with a reddish haze may occur. The patient’s vision loss may be permanent.

Other Causes

Drugs. Chloroquine therapy may cause patchy retinal pigmentation that typically leads to blindness. Phenylbutazone may cause vision loss and increased susceptibility to retinal detachment. Digoxin, indomethacin, ethambutol, quinine sulfate, and methanol toxicity may also cause vision loss.

Special Considerations

Any degree of vision loss can be extremely frightening to your patient. To ease his fears, orient him to his environment and make sure it’s safe, and announce your presence each time you approach him. If the patient reports photophobia, darken the room and suggest that he wear sunglasses during the day. Obtain cultures of any drainage, and instruct him not to touch the unaffected eye with anything that has come in contact with the affected eye. Instruct him to wash his hands often and to avoid rubbing his eyes. If necessary, prepare him for surgery.

Patient Counseling

Orient the patient to his environment. Explain safety measures to prevent injury, and emphasize the importance of frequent hand washing and avoid rubbing his eyes. If vision loss is progressive or permanent, refer the patient to appropriate social service agencies for assistance with adaptation and equipment.