- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •Foreword

- •Introduction

- •Cognitive therapy with in-patients

- •Why do cognitive therapy with in-patients?

- •Specific problems relating to cognitive therapy with in-patients

- •Case example (Anne)

- •Short case history and presentation

- •Assessment of suitability for cognitive therapy

- •Beginning of cognitive formulation of case

- •Session 2 (continuation of assessment for suitability for cognitive therapy)

- •Progress of therapy

- •Session 3

- •Session 4 (three days later)

- •Session 5 (next day—half an hour)

- •Session 6 (next day)

- •Sessions 7–26

- •Outcome

- •Ratings

- •Discussion

- •References

- •Cognitive treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia: a brief synopsis

- •A many layered fear of internal experience: the case of John

- •Second session

- •Tenth session

- •Postscript

- •References

- •Introduction

- •The behavioural model

- •Cognitive hypotheses of obsessive-compulsive disorder

- •The cognitive hypothesis of the development of obsessional disorders

- •The role of cognitive and behavioural factors in the maintenance of obsessional disorders

- •Applications of the cognitive model

- •General style of treatment

- •Assessment factors

- •Problems encountered in implementing assessment

- •Content

- •Effects of discussion

- •More specific concerns

- •Embarrassment

- •Chronicity

- •Broadening the cognitive focus of assessment

- •Treatment

- •Engagement and ensuring compliance

- •Further enhancing exposure treatments

- •Dealing with negative automatic thoughts

- •Dealing with concurrent depression

- •Dealing with obsessions not accompanied by compulsive behaviour

- •Relapse prevention

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Cognitive-behavioural hypothesis

- •Increased physiological arousal

- •Focus of attention

- •Avoidant behaviours

- •The importance of reassurance

- •Principles of cognitive treatment of hypochondriasis

- •Case 1

- •Treatment strategies and reattribution

- •Alternative hypotheses

- •Case 2

- •Cognitive-behavioural intervention

- •Case 3

- •Conclusions

- •Notes

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Prevalence of psychological problems in cancer patients

- •Why use cognitive behaviour therapy?

- •Specific issues in applying cognitive behaviour therapy to cancer patients

- •Grieving for the ‘lost self’

- •Locus of control

- •Physical status

- •Pain

- •Treatment issues

- •Longstanding deficits in coping strategies

- •Specific problems in applying cognitive behaviour therapy in cancer patients

- •Case study

- •Sessions 1 and 2

- •Session 3

- •Session 4

- •Sessions 5 to 7

- •Session 8

- •Sessions 9 and 10

- •Outcome

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Case history

- •Medical assessment

- •Psychological assessment

- •Treatment plan

- •Developing motivation for treatment

- •Rationale for treatment

- •Providing information and education

- •Weight restoration

- •Eating behaviour

- •Binge eating

- •Vomiting and laxative abuse

- •Identifying dysfunctional thoughts

- •Dealing with dysfunctional thoughts

- •Dealing with other areas of concern

- •Maintenance and follow-up

- •Being a therapist with anorexic and bulimic patients

- •References

- •Treatment of drug abuse

- •Drug withdrawal

- •General treatment measures

- •Cognitive models of drug abuse

- •A scheme for cognitive behaviour therapy with drug abusers

- •Engaging the patient

- •Establishing a therapeutic relationship

- •Motivation

- •Rationale

- •The role of negative cognitions in the process of engagement and commitment

- •Cue analysis

- •Problem solving and cue modification

- •Modifying situational factors

- •Cue exposure and aversion

- •Predicting and avoiding high-risk situations

- •Coping with high-risk situations

- •Modifying emotional factors

- •Underlying assumptions

- •Self-schemas in addiction

- •Modifying cognitive structures

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Other clinical approaches with the offender

- •Problems of working with offenders

- •Cognitive-behavioural techniques with offenders

- •General strategies

- •Explaining the role of cognitions

- •Developing trust

- •Collaboration

- •Common cognitive patterns in interaction with offenders

- •Self-defeat

- •Levels of involvement

- •Analysis of the offence

- •Assessing change; deciding on the need for therapy

- •Cognitive therapy

- •Case example

- •Presentation

- •Sessions one to three

- •Background

- •Exposure history

- •Analysis

- •The treatment decision

- •Session four

- •The issue of control

- •The issue of deterrents

- •Explaining the role of cognitions

- •The self-help task

- •Session five

- •Session six

- •Re-analysis

- •Session seven

- •Dependency

- •The issues of wanting to expose and pleasure

- •The issue of dissatisfactions

- •Session eight

- •Session nine

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Suicidal thoughts during therapy for depression

- •Secondary prevention immediately following deliberate self-harm

- •Outline for therapy

- •Vigilance for suicidal expression

- •Case transcripts

- •Reasons for living and reasons for dying

- •Evaluating negative thoughts within a session

- •Inability to imagine the future

- •Some common problems

- •Concluding remarks

- •References

- •Emergent themes

- •Cross-sectional and longitudinal assessment

- •Engagement in and explanation of cognitive therapy

- •Techniques for eliciting thoughts and feelings within the session

- •Dealing with dysfunctional attitudes

- •Other applications of cognitive therapy

- •Application of cognitive therapy to clients with a learning difficulty

- •Case 1

- •Case 2

- •Case 3: Cognitive Restructuring

- •The cognitive framework

- •Different cognitive levels

- •Implications of a ‘levels’ model for therapy methods

- •Theoretical cogency of a ‘levels’ model

- •Future Research

- •Basic research on cognitive processes

- •Future strategies for clinical research

- •Note

- •References

- •Index

96 COGNITIVE THERAPY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

to introspect and give an account of the circumstances of their last relapse. Others will find this more difficult and will need to practise self-monitoring before the factors emerge. For those few people who are unable to offer any cues it may be necessary to interview friends or family members to obtain the relevant information (see Table 7.3).

Problem solving and cue modification

The distinction between general problem-solving strategies as used in cognitive therapy with other disorders and interventions to prevent relapse is an artificial one. In practice many of the problems in the addict’s life link in with the risk of relapse in some way. We will therefore concentrate on how the common problems associated with internal and external trigger factors can be dealt with. The aims of cognitive therapy in this context are twofold: first, to teach the person effective problemsolving skills and coping strategies to deal with addiction, and second, to alter, wherever possible, the underlying predisposition to use drugs or engage in other maladaptive behaviour.

Modifying situational factors

Cue exposure and aversion

Situational factors come up frequently as cues for drug taking. The ideal course of action would be to make individuals invulnerable to the effects of visiting places where they have used drugs before, been with other addicts, seen people intoxicated, etc. This is rarely possible, and so strategies of avoidance and coping with craving need to be taught. There are, however, some behavioural methods which can be used to weaken the power that situational factors exert over the individual. These were initially developed out of classical conditioning theories of addiction, and involve variations of either aversion or exposure. Aversion therapy, which used punishments such as electric shocks or emetics, is less fashionable than in the past, and there is evidence to suggest it is less effective than cognitive-behavioural methods (Marlatt and George 1983). One form of aversion therapy, which uses imagery, may be suitable for selected patients. Cautela’s covert sensitisation (Cautela 1966, 1967) requires the

Table 7.4 Hierarchy of stimuli producing craving

Stimulus |

Estimated craving % |

|

|

Picture of doctor’s surgery |

50 |

Tourniquet and spoon |

60 |

Empty syringe |

65 |

Syringe and needle |

70 |

Syringe and needle containing physeptone |

80 |

Drawing up drug from an ampoule |

85 |

Sitting with syringe and needle against arm |

90 |

patient to visualise in detail a scene where the drug is being consumed, making sure that the cues which have been identified are part of the picture. During this imagery the therapist checks regularly that there is an affective response to the cognitive manipulation, i.e. anticipation and craving. At the point of injection, inhalation, or ingestion, when the addict would experience the effect of the drug, they are instructed to switch the image to an unpleasant one. One of the keys to the successful use of this technique seems to be selecting the most appropriately aversive image. Unpleasant physical experiences such vomiting are often effective, but for others social punishments might be aversive and therefore have more effect, e.g. being discovered intoxicated by your mother. This pairing of images is repeated several times within the session and then the addict practises it several times a day.

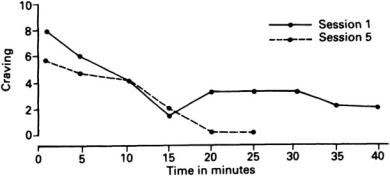

In Jane’s case we chose to use a form of cue exposure rather than covert conditioning. Her sensitivity to the ritualistic aspects of her drug use made it suitable to use an in vivo procedure where the stimuli were the materials of drug taking. Table 7.4 is the hierarchy of stimuli arranged in order of increasing importance. It can be seen that the more closely the situation approximated to actually taking the drug the greater the expected craving. Some of the data from the exposure sessions are presented in Figure 7.1. Within each session there was a reduction in both craving and anxiety over time. Across sessions the level of craving at the beginning of each session reduced, while the time taken for the craving to reduce became progressively shorter. This patient was one of the subjects for a pilot study of cue exposure with addicts (Bradley and Moorey 1987). The method and results presented so far are no different from any purely behavioural exposure task, but the technique was used as part of a cognitive-behavioural programme. There were a number of ways in which this intervention was

DRUG ABUSERS 97

Figure 7.1 Change in craving during exposure to stimulus (tourniquet)

cognitive as well as behavioural. First, the exposure was presented as a behavioural experiment in which the subject tested out her prior belief that in the presence of the stimulus the craving would not reduce. Emphasis was placed on the way that Jane was actively engaged in the process of coping with her craving. The whole exercise became a form of graded task assignment to increase her self-efficacy. Second, at 5-minute intervals Jane recorded her automatic thoughts and images, reinforcing the relevance of cognitive factors in her understanding of the problem. Third, the exercise was used to teach Jane two cognitive strategies, distraction and challenging cognitions, which she could use to cope if exposed to difficult situations in the future.

Thought monitoring during exposure The exposure task provided the therapist with valuable information about the cognitions which Jane experienced when she was craving. These thoughts seemed to be grouped into four main categories which are listed with examples:

Pleasant aspects of drug use

I’d enjoy a fix.

The heroin looks familiar and comforting.

Unpleasant aspects of drug use

I’m not even sure I would enjoy how this drug would make me feel.

Having a fix of heroin would be a hassle.

Intent to use the drug

I’d like to risk taking this linctus.

I want a fix.

Intent not to use the drug

I’m sure I wouldn’t fix this heroin.

I can’t wait to throw this heroin away.

As might be expected the cognitions which were more positive towards drug abuse were reported at the beginning of the sessions when craving was high. As craving reduced, the cognitions focused more on the negative aspects of the experience or the wish to give up drugs. This suggests a correlation between craving and cognitions and raises interesting questions about which changes first in the exposure, thoughts or urges. There may well be an interaction between cognitions and craving such as is found in other feeling states like anxiety and depression. This is a fruitful area for research which has, as yet, hardly begun to be explored. The experience of Jane and other addicts with whom this method has been tried is that over time they experience less and less craving in the face of the stimulus, and develop a sense of mastery over their craving. This method may be associated with high levels of craving at the beginning and it should be used with caution if a patient is already experiencing high craving.

Predicting and avoiding high-risk situations

Situational factors are often so powerful that it is a wise strategy to avoid them unless absolutely necessary. Most addicts are only too aware of this, but some have very rigid and absolute beliefs about the strength of volition, e.g. ‘I have to test myself out’, ‘If I’m strong enough to give up I will be strong enough to face any temptation’. Cognitive techniques can be used to challenge the validity and usefulness of these beliefs. The therapist can ask patients to look at the advantages and