Political Theories for Students

.pdf

C o n s e r v a t i s m

tings, the business of social welfare. Priorities rapidly shifted, however, on September 11, 2001, when the World Trade Center in New York was destroyed, killing several thousand people in the worst act of terrorism known to America. The Pentagon building outside Washington D.C., in a simultaneous attack, was also severely damaged.

THEORY IN DEPTH

True political conservatism argues that the survival of any institution such as marriage, the pledge of allegiance, or free enterprise, means it has successfully served a need. Accordingly, its continuation is necessary for that society or government. Conservative statesman Benjamin Disraeli once argued that constant change should at least defer to “the manners, the customs, the laws, the traditions of the people.” That notion is at the heart of true conservatism. Conservatism is acutely sensitive to the cost of radical change or reconstruction; until the full consequences are understood, such changes may lead to harmful, unintended consequences or other negative or unanticipated effects.

Conservatism vigorously defends the premise that not all people are equal. It supports the idea that all people are created equal with regard to personal freedoms and rights. But it argues strongly for the inherent inequality in talent and initiative. Conservatism considers it a folly to try to level society by social engineering. Accordingly, attempts to distribute wealth evenly or give equal say to those who have earned no vested interest in a matter are clearly suspect.

Persistent themes of traditional conservatism include a universal moral order sanctioned by organized religion, the primary role of private property and a defense of the social order. On the other end is the criticism that true conservatism is interested only in maintaining existing inequalities or restoring lost ones.

The Conservative Split

Traditionalists and reformers differ on issues, but still consider themselves overall conservatives. As President Ronald Reagan once quipped after being confronted with differences among his aides, “Sometimes our right hand doesn’t know what our far–right hand is doing.”

Traditionalists and libertarians splintered following World War II. One of the key thinkers of that period was Richard M. Weaver (1910–1963), who defended the old, agrarian hierarchical values of the

antebellum South. The agrarians argued that a strictly commercial society and civilization, divorced from the land and from tradition, lacked the necessary traditional and spiritual roots to survive. “Southern” conservatism took on its own character, still resenting a strong central government that had taken away states’ rights to secede from the Union, to maintain a slave population and to engage in commerce without federal interference. They would have concluded similarly on their own, they argued, but the issue was the federal government telling them what to do. As Reagan said, “The nine most terrible words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’”

Russell Kirk (1918–1994), who admired Weaver, attempted to define American conservatism as having existed and sometimes dominated Anglo–American culture since the late eighteenth century. Kirk’s conservatism paralleled the nineteenth century British version in proclaiming that social hierarchy was necessary for world order. There were also re–affirma- tions of the divine sources of traditional morality, and a strong belief that property and freedom were inseparable. Kirk adopted and re–promoted many of Edmund Burke’s original views about the natural law doctrine. Kirk found further support in the writings of two Harvard University alumni, Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More. Ultimately, a shared distaste for social engineering and manipulation united traditionalists and libertarians; their shared beliefs included economic libertarianism, social/cultural traditionalism, strong local government, and militant anti–Commu- nism.

Their most common theme was the moral and social good of private property. There was a general support for private enterprise. By the mid–1950s, libertarians and traditionalists regarded personal liberties as virtually incompatible with a welfare state. Communism, therefore, became their nemesis.

John Kekes, in his book, A Case for Conservatism, calls the source of conservatism “a natural attitude that combines the enjoyment of something valued with the fear of losing it.” According to Kekes, all political theorists agree that certain political conditions are necessary to benefit citizens. Those include general civility and equality, freedom, healthy environment, justice, and peace. Kekes argued that even though these conditions are important to all political theories, liberals and conservatives differ by priority. The conservative premise that there are latent effects of social, economic, and moral policies not always readily apparent, and that changing them without un-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 1 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

derstanding their relationship to the whole system may inadvertently alter things for the worse.

Common to conservative thinking has been affirming the need for an orderly, disciplined, unequal society that benefits from appropriate leadership. All political ideologies, arguably, would desire an orderly, disciplined society. The “unequal” element separates conservatism from liberal socialism. Differences among conservatives have focused on exercising “appropriate leadership.” For free–market conservatives, society consists of a hierarchy of talent and achievement, in which an entrepreneurial minority reaps the rewards of its hard work, which gives the minority the incentive to continue creating the prosperity that ultimately will benefit many. Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1925– ) called this the “trickle down” effect.

Patrician conservatives Patrician conservatives, by contrast, might argue continuing the hierarchy of privileges and obligations, but also safeguarding the majority from capitalistic excess. This requires a delicate balance of laws and protections, because “hand–outs” discourage individual responsibility and negate work incentive. Likewise, those who work hard and succeed would lose the incentive, were their wealth distributed to those who did nothing to earn it.

Both views, however, support the need for a solid framework of law and order which counteracts human weaknesses. These flaws weaken society and tear it apart. The key to rewarding capitalistic venture is apparent. But it is harder to find just the right formula to provide minimum protections for the less fortunate without removing their incentive to change their lives. Thus, social welfare programs or a “welfare state” in which government takes on the responsibility for caring for the needy is viewed narrowly and cautiously. For patrician conservatives, each man is responsible for his or her own life, and only those incapable of earning an honest living should receive economic aid.

Some critics challenge that conservatives are also more likely to resist changes to the U.S. Constitu- tion—one dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Conservatives, believing in responsibility for one’s own life, resent shifting such responsibility to government. Pure conservatism supports the idea of equality in man’s basic inherent rights, but not in talents, resources, or in benefits achieved through hard work.

Over the years and mostly as a result of twenti- eth–century immigration and urbanization, the country’s growing diversity contributed greatly to disparate views about government’s role. One can start to see

the connection of these events to the development of American conservatism and liberalism. What is also apparent is the fallacy in trying to attach labels to partisan political views. America’s early Republicans were reformers and revolutionaries. But in the early twenty-first century, the Republicans were generally viewed as the more conservative of the two major parties. Historians have attempted to attach such categories as “neo–conservatism,” “American conservatism,” “the New Conservatism,” and “the New Right.” Each term, however, relates to a period when the issues of the time were redefining political conservatism. But conservatism more recently has usually referred to economic conservatism and social traditionalism.

The Essentials of Conservatism

Conservatism endeavors to preserve the existing order or the continuance of existing institutions, principles, and policies. Its cautious resistance to change is premised upon the belief that would–be reformers do not fully comprehend the interrelationship and interdependency of their proposed change upon other elements of the larger system in which it is a component. English statesman Edmund Burke is most often credited with inspiring the form of conservatism that has its roots in the Western Hemisphere. American conservatism, although vacillating on a continuum, is generally characterized by economic conservatism (maintenance of a free–enterprise system without government interference) and social traditionalism (the upholding of values and principles as envisioned by the founding fathers).

THEORY IN ACTION

Perhaps nowhere has conservatism established deeper political roots than in the Western Hemisphere. Wherever the politics of tradition, wealth, and aristocracy have been a historic force, one will find a strong conservative presence in government. Examples include the Tories or Conservative Party of Great Britain, the Republican Party of the United States, the prior Gaullists of France, the largely dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) of Japan (which, despite its name, is conservative), and the Swatantra Party of India.

Similar polities exist in other countries. In Italy’s May 2001 general election, the right–of–center alliance known as the Casa delle Liberta (House of Freedom) prevailed over the center–left coalition which had ruled the country for the five previous years. In Switzerland, run for more than a century with the Lib-

7 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

erals governing and the Conservatives in opposition a four–party coalition known as the “magic formula” now runs the government. Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has created a parliament. Its two main political forces are the conservative right’s Yabloko and a loose coalition of liberal parties known as the Union of Rightist Forces (URF). Iran has suffered relatively bitter power struggles between conservatives and reformers since 1989.

Conservatism in Great Britain

Britain produced the most famous conservative statesman of the twentieth century, Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965). Twice elected prime minister of the United Kingdom, Churchill conveyed the image of invincible strength and carried his nation through World War II with admirable resolve. He distinguished himself from pre–war Conservative leaders who wanted to negotiate appeasement policies with Adolf Hitler (1889–1945). Churchill refused Hitler’s offers and organized one of the boldest military strategies ever. Together with Allied forces, Britain held off the Germans.

The war, however, had devestated Britain. Then, in one of the most striking reversals in political history, Churchill’s Conservative Party was soundly defeated by the Labour Party in the general election in July, 1945. Rather than a personal vote of censure against Churchill, the defeat was probably a reaction against twenty years of Conservative rule, a desire for social reconstruction, and uncertainty about the aggressive international policies espoused by the Conservatives. He easily won a seat in his new district of Woodford, which he held for the last nineteen years he spent in Parliament. He immediately resigned as prime minister. The resulting Labour government passed a National Insurance Act and a National Health Service Act.

Churchill, as leader of the opposition from 1945 to 1951, continued to enjoy a worldwide reputation and warned the Western democracies to stand firm in the face of the growing threat of the Soviet Union. Churchill’s speeches created a storm of protest and controversy in the West, but events soon confirmed his views of world events and the rapidly developing Cold War. The Conservatives won a narrow victory in 1951, and Churchill was returned to his position as prime minister.

One positive aspect of conservatism was that Britain’s Conservative Party did not alter any of the social welfare programs enacted by the Labour Party in the late–1940s—although the Conservatives probably did not do so because they had no mandate, not

Sir Winston Churchill. (The Library of Congress)

much money to spend, and the programs were popular and were working in the relative prosperity of the early–1950s. More so than the Labour Party, however, the Conservatives wanted to maintain a colonial presence on many of Britain’s possessions around the world, but economic problems at home and the waves of independence ferver rendered this impossible, and the British Empire continued its rapid decline.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s leadership in the Conservative Party enjoyed a clear majority from 1979 through 1990. Thatcher vowed to reverse Britain’s economic decline and reduce government’s role in the economy. Her policies included abolishing free milk in the schools, curbing trade union power, expanding private–sector roles in health services and pensions, and deregulating some sectors to break up monopolies. Thatcher is also remembered for her strong position over the Falkland Islands, which Argentina and the United Kingdom both claimed during a crisis in 1982. When Argentine forces occupied the islands, Thatcher’s government sent troops to defeat them. Thatcher, despite high unemployment rates, led the Conservatives to a sweeping victory in the parliamentary elections of 1983, bolstered mostly by her successful Falkland Islands policy.

Eventually, even influential figures in Thatcher’s Conservative Party resisted some of her changes, es-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 3 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Sir Winston Churchill

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, the famous British prime minister, soldier, and author, was the quintessential conservative. Churchill, born into a military family and educated at private schools in England with unremarkable academic achievement, was first commissioned as an officer in the 4th hussars and served his time in India and the Sudan. After resigning his commission, he made a name for himself as a journalist after writing about his own capture, imprisonment, and escape from the Boers. He was elected to Parliament in 1900 as a Conservative, but switched to the Liberal Party and was appointed, respectively, as undersecretary for the colonies, president of the Board of Trade (1908), home secretary (1910), first lord of the admiralty (1911), minister of munitions (1917), secretary of state for war and air (1918), and colonial secretary (1921), where he helped negotiate the treaty that created an Irish Free State.

Churchill eventually returned to the House of Commons and became prime minister in a Conservative government. He enjoyed great success and faced harsh criticism for many of his ideas and policies. He was a great orator and war leader whose resolve and refusal to appease Adolf Hitler was an important fortifier for European resistance, and ultimately contributed to the Allied victory in World War II. Churchill despised all forms of totalitarian and Communist governments, and steadfastly believed in the moral superiority of democracy and its eventual triumph. He warned the House of Commons in 1935 not only of the importance of “self–preservation but also of the human and the world cause of the preservation of free governments and of Western civilization against the ever advancing sources of authority and despotism.” Churchill, who coined the expression, “Iron Curtain,” was the first to warn the U.S. of the threat of Soviet expansion. An eloquent and talented literary writer, Churchill won the Nobel Prize in Literature for The History of the Second World War. He resigned from office in 1955 due to poor health and died ten years later. Churchill remains the most admired hero of many politicians, including U.S. President George W. Bush and New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

pecially the controversial poll tax and her negative attitudes toward the then European Community (EC). John Major, a New Democrat, replaced her in 1992. Ultimately, the reign of the New Democrats was short–lived when the Labour Party, downtrodden and traditionally identified with the poor and the pub- lic–housing tenants, built a more dynamic image around new leader Tony Blair (1953– ). His party remained in control in 2001.

America’s Own Breed of Conservatism

Democracy and industrialism proved more potent forces than Edmund Burke’s principles. And America had its own signature conservative, Henry Ford (1863–1947). The quintessential capitalist and automobile manufacturer was the most conservative of men in his personal habits and opinions. Known for his anti–union labor policies, he employed spies and company police to prevent workers from unionizing his Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. He promoted Christian values and principles among his laborers, and monitored personal habits and lives, such as discouraging smoking and alcohol, and providing family housing, counseling, and community events. He also published a weekly journal, the Dearborn Independent, which contained several anti–Semitic articles in its first issues. Ford, however, won respect as an inspiration for change.

McCarthyism

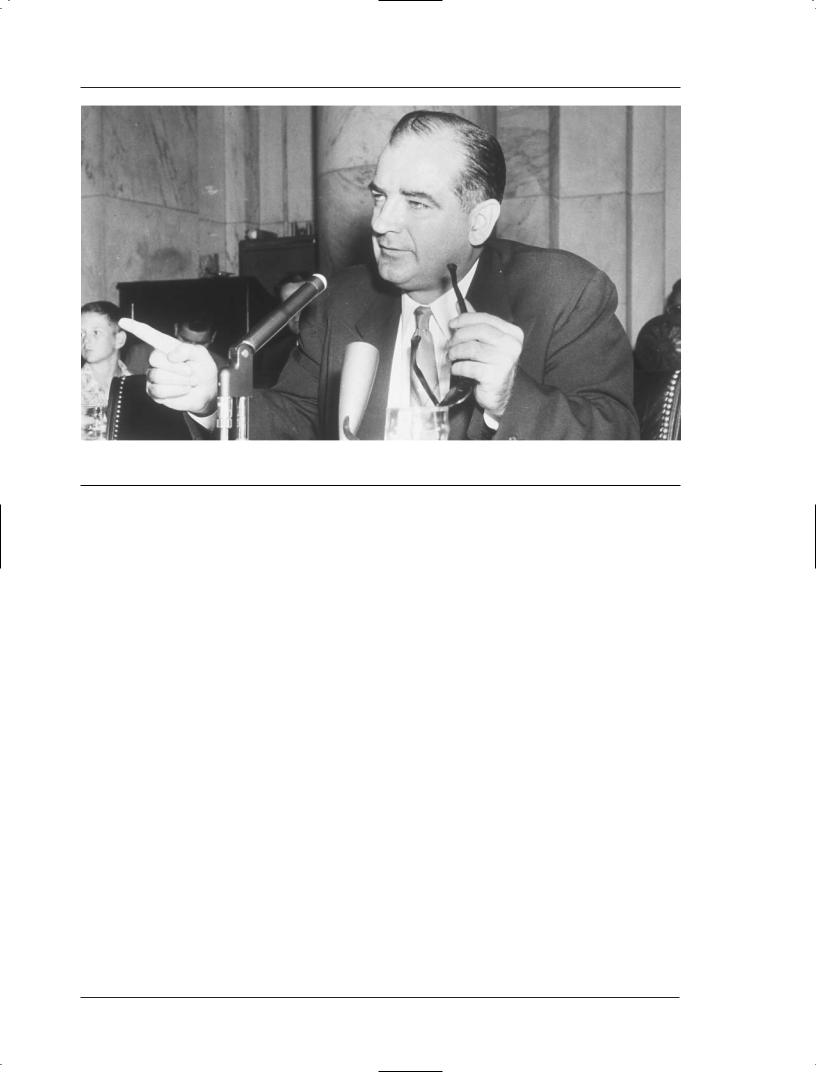

Forever linked to extreme post–war conservatism is Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph R. McCarthy (1909–1957), the man ultimately responsible for the label “McCarthyism.” His U.S. Senate tenure occurred during the Cold War and America’s fight to rid itself of Communism. In her book, The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History With Documents, author Ellen Schrecker described the shift from American tolerance for Communism to American antagonism. She noted that comparative tolerance grew out of a World War II alliance with the Soviet Union, but turned into an aggressive stance against Communism, premised mostly upon the growing hostile relationship with the Soviet Union following the war. In the first five years after the war, the Soviet Union attempted government takeover of the countries it had helped liberate from Hitler’s regime during the war. It overtook Poland’s government in 1945, pressured Turkey and Iran in 1946, partly instigated the Greek Civil War in 1947, caused the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia and the blockade of Berlin in 1948, and detonated an atomic bomb one year later. Peaceful coexistence no longer appeared viable, and the United States remained the only free nation strong enough to stave off

7 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy during a hearing. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Communist aggression. The world actually hovered on the verge of another world war. Moreover, the threat of internal infiltration of Communist party members and spies caused near panic in America.

As Schrecker wrote, “An important element of the power of a modern state is its ability to set the political agenda and to define the crucial issues of the moment, through its actions as well as its words.” This is particularly important when we consider the difference between conservative versus liberal interpretation of the perceived “Communist threat” to the world or to America in the 1940s. In any event, the threat was real, and based on real evidence, and it is true that individual Communists who had infiltrated the government did steal secrets. It is also true that Communist agitators had infiltrated America’s labor unions. However, the response to the threat bordered on frenzy and serious violations of civil liberties. In the late 1940s, for example, the Immigration and Naturalization Service began to round up foreign–born Communists and labor leaders for deportation and detention without bail. It has been argued in retrospect that the Truman administration, fearing a Republican Congress that might not allocate enough funds for anti–communist activities or the Administration’s foreign policy programs, exaggerated the Communist threat. In March 1947, the president went before a special session of Congress and pled the case for the as-

sessment of Communist infiltration within American society. Congress then created the House Un– American Activities Committee (HUAC) to investigate the extent of the perceived threat. The institutions which best exemplify the McCarthy era were these congressional investigative committees.

Red Scare begins Politically, the move backfired. In 1947, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (1895–1972) testified before the HUAC and created such fear of an internal Communist threat that the Republican–domi- nated Congress launched an all–out attack on anti–American sentiment and activity. Communists were summarily dehumanized and transformed into ideological criminals. Protecting the nation from this danger became the American political theme of that era, which continued well into the 1950s.

The First Amendment’s freedom of speech and press does not protect those preaching the violent overthrow of the government. Therefore, Congress, under the HUAC, began a concerted effort to investigate, expose, and prosecute Communist sympathizers. Communist labor leaders were involved in many highly publicized strikes in U.S. defense industries. Although the Communist–dominated Fur and Leather Workers union posed little threat to national security, the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) as well as various maritime unions, were of more

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 5 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

concern. The politically left–led union leaders became the subjects of investigation and exposure, and many, along with other party leaders, were prosecuted and incarcerated for alleged anti–American activity. The government also implemented an anti–Communist loyalty–security program for government employees in March 1947. Major prosecution trials of espionage agents such as Alger Hess and Ethel (1915–1953) and Julius (1918–1953) Rosenberg received enormous publicity and enhanced the credibility of a real threat to the country. The notorious spy cases of the early Cold War period seemed to punctuate J. Edgar Hoover’s contention that “every American Communist was, and is, potentially an espionage agent of the Soviet Union.” The Smith Act trials of the top leaders of the American Communist Party in 1949 helped the U.S. government unify all the anti–American themes to bolster its contention that the Communist Party represented an illegal conspiracy under Soviet control and direction.

Using these events to punctuate their criticism of the liberal social policies of the New Deal during the previous Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration, conservative politicians, mostly Republican, accused the Democrats of being soft on Communism. Congressional investigating committees, such as McCarthy’s Permanent Investigating Subcommittee of the Government Operations Committee, and Senator Pat McCarran’s Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, paralleled the activities of the HUAC. But “McCarthyism” stood for the publicizing or directing of accusations of disloyalty, regardless of evidence.

McCarthy goes too far McCarthy directed his attention to the media and the educational systems because they were viewed as shapers and molders of public opinion. One by one, Hollywood producers, actors, and artists, as well as college educators, were subpoenaed to testify before the congressional subcommittees about their knowledge of and/or affiliation with the Communist Party. Hollywood blacklisted actors who named their colleagues. Witnesses who refused to testify were prosecuted for contempt of Congress, labeled “unfriendly witnesses,” and stigmatized equally. The work of the Congressional subcommittees trickled down to state and local levels with their own Un–American Activities Committees. Private employers cooperated in the probes, resulting in public exposure of Communist sympathizers, who then lost their jobs and generally faced ostracism from a patriotic public.

The official manifestations of McCarthyism— public hearings, FBI investigations, and criminal pros- ecutions—ultimately proved mild compared to the

horrors of Stalin’s Russia. Nonetheless, in retrospect, they have negatively represented conservatism in the extreme. The government’s characterization of the Soviet/Communist threat invoked the criminal justice system and enhanced the American public’s perception of domestic Communists as criminals. However, according to Schrecker, even at its peak, the Communist Party had a high turnover rate, and by the early 1950s, most party members had actually quit. The “Red Scare” resulted in numerous violations of civil liberties and freedoms of those whose ties with Communism may have been only incidental or not threatening to the United States.

Here again, is another application of conservative versus liberal sentiment. Extreme conservatism may favor incidental or mild abridgments of civil liberties as a necessary price to secure free enterprise and a way of life that nurtures such freedoms. Alternatively, liberalism believes personal freedom and liberty trump the needs of national freedom from foreign or internal threat. In retrospect, McCarthy–era critics call it the worst kind of conservatism. On the other hand, conservative politicians argue that such tactics would not have been necessary but for the lax policies of liberal politicians and/or the socialistic policies of the New Deal. They argue that such policies ultimately created an environment in which workers felt they were entitled to equal shares of economic prosperity, regardless of personal input. The ultimate fall of Communism and the Soviet empire during the late twentieth century, and a commensurate rise in global free–enterprise systems and governments, emphasize their point.

Ultra–Right Conservatism

Important to the application of the freedom of speech and association to extremist groups, such as the Communist Party, is that they may enjoy First Amendment protections, even if their views are repugnant to some or outside the mainstream. If Communism is associated with liberal socialism near one extremity, then ultra–conservative groups such as the Moral Majority and John Birch Society might occupy the other end. These groups have grown over the years, particularly stimulated into activism during periods of comparative liberal political thought. Many of them have targeted a growing federal bureaucracy and the recovery of perceived lost liberties and/or freedoms (not to be confused with the work of the ultra–liberal American Civil Liberties Union).

Private citizen Robert Welch (1899–1985) founded the John Birch Society in 1958 to preserve and promote America as it was originally established:

7 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

a Constitutional Republic. It embodies what is perceived as extreme right–wing conservatism, even though many Americans not part of the Society’s membership agree with its principles. Because the Society refers to the country’s Judeo–Christian heritage and moral values, it is often criticized as having a religious agenda or representing the Christian Right. Yet, looking to the country’s history, the values the Society promotes are similar than those the new republic promoted in the late 1700s: a belief in the family as the primary social unit, a support for a free–mar- ket system and competitive capitalism, and a protection of the personal freedoms the original framers of the Constitution contemplated.

John Birch (1918–1945) was a Christian missionary the Chinese Communists killed following World War II. His death symbolized for the Society a unified resistance to a “new world order,“ a love for freedom, and the rejection of totalitarianism “under any label.” According to the Society’s Internet website (http://www.jbs.org), its members believe “that the rights of the individual are endowed by his Creator, not by governments...”

In America’s early days, the John Birch Society may not have been able to accommodate the number of persons clamoring to join such an organization. But in the twenty–first century, the multiplicity of cultures, values, and religions within the United States has alienated the Society from those who favor diversity. Despite the Society’s invitation to “individuals from every walk of life and from all ethnic, racial, and religious backgrounds” who share a love for liberty, the Society remains stigmatized as representative of an ul- tra–right minority attempting to turn back the clock. For example, attitudes toward the “family” as a primary social unit have changed tremendously, particularly in the last century, when single parenthood, one–parent families, and homosexual marriages affected many lives. Another issue polarizing the Society against more “liberal” conservatives is the Christian theme, admittedly representing the majority of citizens and the country’s heritage, but no longer considered “politically correct” within a diverse contemporary citizenry. This serves as a good example of the changing nature of conservatism and its relevance to time along a continuum: what was once considered mainstream thought later becomes threatened and must be defended.

Media Bias

Another important consideration affecting the balance of conservatism versus liberalism in the U.S. is the presence or absence of media bias. Over the years, various accusations have been directed at both

sides, claiming that the media attempts to advance its own political agenda by slanting the news. There is apparently some truth in this, straight from the media itself. In The Media Elite, authors S. Robert Lichter, Stanley Rothman and Linda S, Lichter summarized the results of their interviews with 238 journalists from the entire spectrum of mass media. This included reporters, editors, executives, anchors, correspondents, and department heads from America’s most influential media outlets: New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Time, Newsweek, U.S. News & World Report, CBS, NBC, ABC, and PBS, among others. The results, though dated, (1990), tend to support what many have claimed for years. A majority, 54 percent, described themselves as left of center. Only 17 percent described themselves as right of center. While 56 percent responded that they believed their colleagues were on the left, only eight percent responded that their colleagues were on the right.

Moreover, journalists’ descriptions of themselves on a wide range of social and political issues revealed the following: 90 percent believed in abortion rights; 75 percent believed homosexuality is not wrong; 53 percent believed adultery is not wrong; and 68 percent believed government should reduce the income gap.

The criticism against a biased media is, of course, that the American people deserve to know all, and not select, facts on any given issue, and that journalists should be compelled to impartially present them. Eva Thomas, Washington bureau chief for Newsweek magazine, commenting on House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s (1943– ) charge that the media was biased, noted, “Particularly at the networks, at the lower levels, among the editors and the so–called infrastructure, there is liberal bias.” And Bernard Goldberg, CBS News correspondent, wrote in an editorial for the Wall Street Journal, stated that the liberal bias in the media is so “blatantly true that it’s hardly worth discussing anymore.” It’s usually not something the media plans to do—or is necessarily even conscious of doing. Goldberg added that bias is something that comes out of reporters naturally, whether they like it or not.

According to a 1996 Freedom Forum/Roper Center survey of 139 Washington–based bureau chiefs and congressional correspondents, 89 percent voted for Democrat Bill Clinton. (Figures for the 2000 election were not yet available.) Richard Harwood, former assistant managing editor and ombudsman for the Washington Post, also noted in 1996 that, while the majority of American journalists do their best to remain

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 7 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

impartial, “the journalist without those allegiances is rare indeed...”

Conservatism in the Courtroom

One of the most important ways in which conservatism affects the daily lives of Americans is reflected in political appointments to judicial posts, particularly those by U.S. presidents of justices to the higher federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. Since these are appointments for life, they are not taken lightly.

Only federal judges, and a handful of state judges, are appointed for life, barring impeachment. In all other states and in local governments, most judges are elected and reelected by popular vote, and for a specific term. In the abstract, it has always been the desire to make judges, in the words of John Adams’s Massachusetts constitution, “as free, impartial and independent as the lot of humanity will admit.” But in a political system where social issues define party pol- itics—and where jurisprudence largely affects social issues—alignment and/or labeling is inevitable. A judge, whether elected or appointed, assumes his or her post based on how others perceive he or she will run the bench—conservatively or liberally. Nowhere is it more important that a justice stay politically independent than on the U.S. Supreme Court, for the “supremacy clause” of Article VI of the U.S. Constitution makes the Constitution and treaties “the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby.” The top court has the final opinion on Constitutional interpretation.

A president’s conservative or liberal leanings, however, may greatly affect his judicial selections. Of course, the Constitution provides a check and balance power of review and confirmation by the Senate for each presidential selection.

The Supreme Court decides some of society’s most profound issues, and its ideological makeup during any era may affect decisions on sensitive matters: rights and protections of the unborn, rights of minorities, rights of speech and personal freedom, employee rights, the rights of the accused, rights of the incarcerated, and rights of non–citizens and aliens, among others. Although conservative or liberal leanings may suggest bias in interpreting a law or constitutional provision, a minimum of four other justices would have to agree in order to carry a majority in a decision.

Although a Supreme Court decision may be labeled conservative or liberal, there is a distinction between political conservatism and judicial conservatism. Politicians make the laws; justices interpret

them. When the terms refer to court decisions, conservatism usually means a narrow interpretation of existing law, limited most often by the plain or express language contained therein. This is sometimes called “strict constructionism.” Conversely, courts rendering what may be labeled as a liberal opinion in any matter have broadly interpreted the plain language of a law in order to fit the specifics of the case before them.

Conservatism of justices In one sense, the conservatism of justices parallels true conservatism more so than that of politicians. Justices and judges are extremely hesitant to interpret a law in such a way that it undermines the original legislative intent; in fact, they will often go beyond the arguments made by attorneys in the case, and take it upon themselves to seek the legislative history of the law in question. This is true even if a more liberal or broad interpretation may be more just or favorable under the certain sets of facts before the Court. A court of law has no power to alter or amend existing law, and many times it will state in its opinion that the litigants need to seek legislative rather than judicial relief, i.e., consult their local state representatives or senators to discuss amendments to the written law. However, courts may and often do find certain laws to be unconstitutional under state or federal constitutions, and such a decision by the highest court with jurisdiction over the matter renders the previous law void. And if, in retrospect, a court deems an earlier decision has had far too liberal or conservative effects when applied to other situations, it will attempt to delineate or contain that decision in a subsequent one.

Thus, often in subsequent cases that would require the application of the same law or decision, but with a different set of facts, the Supreme Court will chip away exceptions to the general rule, resulting in a more narrow application of its earlier decision. Although the Supreme Court is empowered to reverse its own decisions, it rarely does. The justices take ultimate care that their decisions are legally and constitutionally sound.

Miranda rights Take, for example, the case of Miranda v. Arizona (1966), in which a liberal Supreme Court held that confessions or responses accused persons gave when law enforcement officials interrogated them could not be used as evidence in court unless the accused had first been advised of such legal rights as not speaking and having legal counsel. These have since been generally called “Miranda rights.” While this decision may have been constitutionally sound at the time, the reality of its sweeping effect and/or its

7 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

application to real cases convinced many Americans that perhaps the Court had been a little too liberal in its constitutional interpretation of the rights of the accused. As a result of the Court’s decision, repeat offenders and many persons accused of violent and/or heinous crimes were being released from custody or incarceration. This could have been because of some minor technical oversight or stress–induced mistake on the part of an arresting officer who may have failed to fully advise an accused person of his or her rights.

Since 1966, the Supreme Court has invoked Miranda many times, making exceptions or clarifying the general rule. In the 2000 case of Tankleff v. Senkowski, the Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Martin Tankleff, convicted of murdering his parents in Belle Terre, New York. Tankleff claimed that his confession, given after he was read his Miranda rights, was nonetheless tainted by police questioning that occurred before they advised him of his rights. This case established no legal precedent.

Supreme balance Conservatives and liberals try to affect the Supreme Court through congressional pressure to increase the number of justices on the Court. Since justices are appointed for life, members of Congress often want to neutralize the effect of sitting justices. The most recent attempt came during the Clinton administration. Even though Clinton had already nominated two justices during his tenure, liberals Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933–) and Stephen Breyer (1938–), Congress considered a measure to add two more. Ostensibly it was argued as a measure to reduce a backlog of cases, but in reality it was an attempt to affect the conservative/liberal balance. Congress has the constitutional authority to fix the number of associate justices on the Court; the current number under the chief justice is eight. This most recent attempt to increase the number failed.

In fact, the nine justices who sat on the court going into the new millennium may represent one of the most balanced groups of justices ever to sit concurrently. Three are known conservatives, three are known liberals, and three often provide the “swing vote,” which may carry the Court one way or the other in a given case.

William Rehnquist, originally appointed as associate justice in 1971 by a conservative President Nixon, was nominated chief justice by Reagan in 1986. He is known for his hard–line conservative position on most constitutional matters. Another conservative is Clarence Thomas (1948– ), whom Bush the elder nominated in 1991. Antonin Scalia (1936– ), nominated by Reagan, took his oath in 1986. He is the

third traditionally conservative justice sitting on the top court.

Ginsburg, nominated by Clinton in 1993, is widely known as a liberal. So is Breyer, appointed in 1994 to replace Harry Blackmun (1908–1999). The third liberal justice is John Paul Stevens (1920– ). Conservative President Gerald Ford (1913– ) nominated him to the top court in 1975. After his appointment, however, he shifted to the left.

Although Reagan appointed justices Sandra Day O’Connor (1930– ) and Anthony Kennedy (1936– ), in 1981 and 1986, respectively, they have, in fact, proved to be middle–of–the–roaders, often taking moderate stances independent of any other justice. This has also been true of David Souter (1939– ), a Bush nominee in 1990. Souter, Kennedy, and O’Connor, therefore, play particularly important roles in delicate decisions the public may erroneously perceive as conservatively or liberally biased.

The Court faced such an accusation following its decision in the Bush–Gore presidential campaign of 2000 involving as many as 15,000 absentee ballots from Florida’s Seminole County. The U.S. Supreme Court found that the manual recount of votes ordered by the Florida Supreme Court violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution by treating voters’ ballots differently and by conducting it erratically and arbitrarily without proper standards. The media wasted no time labeling judicial players by race, party, and political and personal preferences. Over the years, Democratic governors had appointed all seven Florida Supreme Court justices. But the U.S. Supreme Court comprised a mix of Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives. When the majority ruled against the Florida court, some liberals in the media were openly skeptical about an undercurrent of a “re- sults–oriented” majority seeking a high–minded legal rationale to front their own political leanings. The Supreme Court, however, simply but firmly denied the inference.

ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL RESPONSE

In his essay entitled, “Conservatism Is a Vital Political Ideology,” found in Politics in America: Opposing Viewpoints, Heritage Foundation president Edwin J. Feulner Jr. attributed to conservatism the conquering of Soviet Communism, the promotion of democracy throughout the world, and the strengthening of the U.S. economy. Feulner argued in his essay that the governments of Eastern Europe were turning to conservative Americans and their free–market ideas

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 9 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

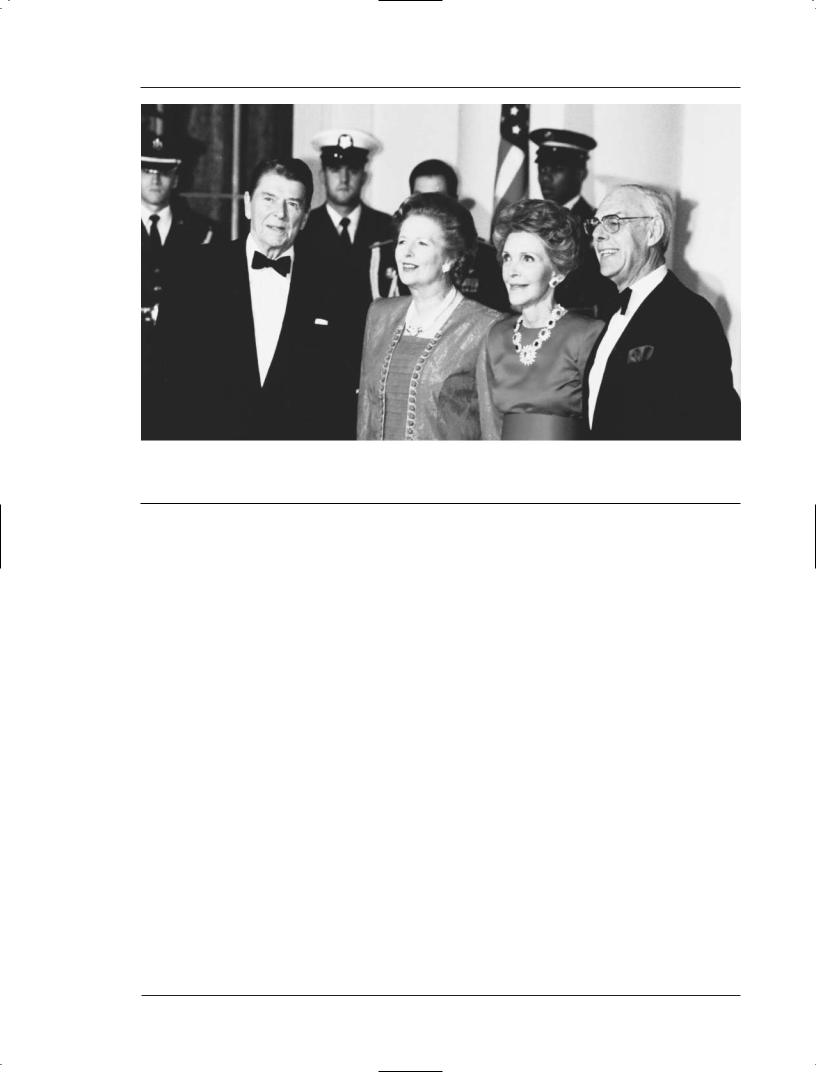

U.S. President Ronald Reagan (left) with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, First Lady Nancy Reagan, and Lord Dennis Thatcher at a White House State Dinner in 1983. (Corbis-Bettmann)

for advice. In Warsaw and Prague, Feulner said, the people wanted capitalism, not lectures on capitalist exploitation.

In an opposing viewpoint entitled, “Conservatism is a Declining Political Ideology,” Democrat David Dinkins, former New York mayor (1989-1993), argued that with the fall of the Soviet Union, conservatism lost its cause, i.e., in Dinkins’s words, “No Enemy, No Energy.” He also blamed the fear of Communism for “block[ing] the path to progress here at home.” Said Dinkins:

The conservatives regaled us with tales of resurgence while the rest of the world went whizzing by. So now we can remember the touching speeches and sentimental images of the 1980s while we travel across roads and bridges that are crumbling, to take our kids to schools that aren’t teaching, to prepare them for life in a global economy that suddenly threatens to leave them behind...Military might [has become] the sole measure of national security, leaving no room in our calculation of American strength for infant mortality, literacy, or economic opportunity.

When the Republicans gained control of Congress in 1994 it often led to policy standoffs with the president which resulted in government shutdowns, and opinion polls showed that people sided with Clinton. “Given the political excitement in the 1980s, the governmental failings of conservatism in the 1990s are nothing short of astonishing,” wrote Alan Wolfe in an article in the June 7, 1999 issue of The New Republic. Conservative figures such as Pat Buchanan (1938–), Newt Gingrich, and Bob Dole (1923–) were stereotyped as politicans who looked out for big business while not showing much concern for ordinary people facing economic hardship. Sometimes the stereotype was justified, often it was not, but it stuck. Indeed, when George W. Bush campaigned for president in 2000, his platform called for the toned–down version of conservatism which he labeled “compassionate conservatism.” This softening of the conservative image may have given Bush the extra boost he needed in one of the closest elections in American history.

Conservatism ran into some problems in the 1990s, particularly in the United States. It was a belief held by many people—many registered voters—that conservatism was an ideology of the rich, and the 1992 election of Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton was in part a rejection of conservative politics.

Out of Touch?

Of course, the most consistent criticism of conservatism is that its resistance to change has resulted in it being outdated and out of touch with the real world. Liberals may argue that a demand for change is simply a corrective measure to bring forward a lag-

8 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |