Political Theories for Students

.pdf

F a s c i s m

order to elevate his status as Il Duce to that of an all–powerful and all–knowing ruler of his people. Every public appearance was carefully choreographed to ensure his physical appearance and gestures were appropriate for each specific situation, and experts were employed to ensure the correct use of setting, lighting and music, especially for photographs, which were invariably taken from below to disguise his diminutive stature.

Fascism Permeates Life

Throughout Italian society the ideology and symbols of Fascism were inescapable. It appeared that almost every official, from local to government, wore a different uniform each day, and all street corners were clothed in nationalist images and the painting of Fascist slogans. The teaching of Fascist values and ideals and the promotion of the qualities required to create the new Italy invaded all aspects of daily life—in schools, at work, in leisure pursuits, in the press, and in the media. The principal target of manipulative policies were the young, who embodied the desired Fascist attributes of strength, energy, and loyalty, and they were exposed to indoctrination, not only in school but also in the Fascist promotion of sport and physical fitness, and in political youth organizations, such as “Little Italian Girls” and “The Sons of the She Wolf.” For these groups, the focus was on cultivating the importance of militarism and conformity, with boys as young as seven receiving training in military drill and gun skills, and the program’s popularity resulted in over five million young members by the 1930s. Sport also played an important role in the advancement of Fascist propaganda with its wide appeal, its ability to divert the public’s attention from other matters, and its manifestation of Fascist belief in national pride and a sense of belonging. These sentiments were echoed in the media, who were tightly controlled and prohibited from printing or broadcasting anything which the Fascist censors considered would shed a poor light on the image of either Mussolini or his regime.

One area of policy that could not disguise its consequences with censorship or propaganda was the complex relationship that existed between the Fascist regime and the economy. Initially, the inconsistent economic and social policies introduced by Mussolini failed to address the deep–rooted crisis that consumed Italy in the aftermath of World War I. The continual rise of unemployment was exacerbated by the Fascists’ unsuccessful attempts to manipulate the value of the lire, which they carried out in the hope of improving their economic competitiveness. The arrival of the international depression in 1929 deepened Italy’s problems and, by 1932, wages had halved in

real terms, becoming the lowest in western Europe. Although Mussolini readily acknowledged the drop in the Italian standard of living under Fascism, his response of “fortunately, the Italian people were not used to eating much and therefore feel the privation less acutely than others” did not fill his supporters with any measure of confidence.

The decision amongst the PNF was for an increase in government intervention, with the immediate result that strikes became illegal, and in exchange employers were forced to offer improved wages and conditions to their workers. Italy then moved towards becoming a corporate state, in which each industry came under the control of a corporation consisting of representatives of employers, workers, and government officials, though ultimately these corporations were under the control of Mussolini. In practice, the labor force received very little consideration and the state effectively stepped back and encouraged employers to manage their own affairs, the only apparent measure of intervention occurring when the state rewarded big business with state investment and government contracts.

There then followed a period of consolidation, during which measures introduced by the Fascist Regime—such as the “Battle for Grain,” in which offering farmers incentives to increase production ensured almost total self–sufficiency in wheat produc- tion—created substantial improvements in the country’s economic and social conditions. Mussolini also introduced a vast program of public works, under which the Pontine Marshes were drained, public buildings were improved, ancient monuments were restored, and hydro–electric power was developed to counterbalance Italy’s lack of coal and oil. This phase of Fascism also witnessed the creation of the autostrada (motor ways), and the improvements he made to the railways and airlines gave rise to the myth that Mussolini’s power was so great that he could even make the trains run on time.

Italian Foreign Policy

One of the most significant and enduring legacies of Italian Fascism was Mussolini’s signing of the Lateran Treaties with Pope Pius XI (1857–1939) in 1929. This gave official recognition of the Vatican as an independent state and confirmed Catholicism as the state religion, in the process bringing to an end a half–cen- tury of discord between the state and the Church. These successes, and the growing confidence that they instilled in Mussolini’s regime, led to the development of an aggressive foreign policy, beginning with the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and culminating in the “Pact of Steel,” signed in 1939 to cement the alliance between Italy and Nazi Germany.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 0 1 |

F a s c i s m

Militarism, and the belief that war was essential to the creation of the new order, was a central element of Italian Fascist ideology and figured highly in Mussolini’s plans from the moment he secured power. He temporarily seized the Greek island of Corfu in 1923, but it was his invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935 that won him acclaim from within all sections of Italian society and inspired him to proclaim the beginning of the new Italian Empire. However, some of the barbarous methods employed to secure victory included chemical warfare and mass executions of native tribesmen, a radical departure from previous campaigns. Shortly afterwards, the sanctions imposed on Italy by the League of Nations, in response to Italian military aggression, led to Mussolini forging closer links with Germany, who had stood by Italy over the Ethiopian invasion. The “brutal friendship” was affirmed by the signing of the Rome–Berlin Axis in 1936 and later tightened by the “Pact of Steel” in 1939. Both countries joined in supporting Francisco Franco’s nationalist revolt in the Spanish Civil War and, as the specter of World War II rapidly approached, it was apparent that Mussolini and Italian Fascism were becoming increasingly influenced by the ruthlessness and success of Nazism.

Adopting Hitler’s belief in its purely nationalistic nature, Mussolini curtailed his promotion of “universal fascism,” in which he had invested a considerable amount of capital and effort to encourage foreign forms of fascism, including the British Union of Fascists. Of greater concern to the Italian people, and to governments throughout Europe, was the introduction, in 1938, of anti–Semitic laws into official Italian policy. Until this development, anti–Semitism had no place in Italian Fascism, with the PNF including a number of Jews among their membership, and its introduction proved unpopular throughout Italian society and provoked opposition from many organizations, including the Vatican. By the time the Second World War broke out, a great deal of division existed within Italy—and within the PNF—over the association with Germany, and cracks began to appear in Il Duce’s veneer of invincibility.

World War II

When war broke out in September 1939, Mussolini, who was fully aware of his country’s military weakness, initially reneged on the “Pact of Steel” because he had previously informed Hitler that Italy would not be prepared for war before 1942. This declaration of neutrality only lasted until June 1940 when Mussolini, exhibiting his capacity for opportunism, sensed that a German victory was imminent and feared missing out on a share of the spoils. Still

harboring hopes of extending his Italian Empire into the Balkans and Africa, Mussolini’s aspirations had outgrown his military capabilities and German forces had to come to the Italians’ rescue, both in Albania and North Africa. For the remainder of the war, Italy tagged along as the weaker member of the Axis partnership, with Italy’s interests becoming subordinate to those of Germany, resulting in the erosion of Mussolini’s authority.

Support for the Fascist regime collapsed in the face of constant military defeats and, with the invasion of Sicily and southern Italy by the Allies in 1943, there was a rapid growth of partisan resistance throughout Italy, plunging the country into civil war. As a result, many of the Fascist Grand Council turned on their leader and, on July 25, 1943, King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed, then arrested, Mussolini, and surrendered Italy to the Allies. In an attempt to regain control over Italy, Hitler rescued Mussolini from imprisonment and installed him as the puppet ruler of a brutal Social Republic in the north of Italy. With the aid of the Black Brigades, which were the vicious secret police force controlled by the Nazi SS, Mussolini endeavored to recreate his original vision of a Fascist state, but his personal stature had now crumbled and there was a total lack of support for his philosophy. The demise of Il Duce and Italian Fascism reached a violent conclusion when, on April 28, 1945, while fleeing from the approaching Allies, Mussolini was captured and shot by Italian partisans, who then strung his body upside down in Milan as a powerful symbol of the death of Italian Fascism.

Fascist Government Rule in Germany

The only other fascist regime to assume the power of government was the National–sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist Party of German Workers), who became universally known as the Nazis. After rising to power through democratic means in January 1933, the party wasted no time in diminishing the authority of the Reichstag, and establishing the creation of a Nazi state. One month after the elections the parliament buildings were destroyed by fire and Communist agitators were accused of arson. Using this as vindication, the Communist and the Social Democratic parties were subject to mass attacks and violent suppression, with neither offering any resistance. By the time the Enabling Act was passed in March 1933, removing all legislative powers from the Reichstag and passing them to Hitler’s Cabinet, all opposition parties had been abolished and it became a criminal act to even attempt the creation of any new party. The Enabling Act, which had effectively granted dictatorial powers to Hitler and signified the

1 0 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Adolf Hitler

The architect of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889 in Braunau on the River Inn, Austria. The son of an Austrian customs official, Hitler followed an undistinguished school career at Linz and Steyr, with an equally unremarkable spell as a would–be art student in Vienna. By 1914, he had cultivated a lifelong hatred for academics, Jews, and socialists, while his voracious reading had instilled him with a fervent belief in German nationalism and anti–Marxism.

Hitler moved to Munich and, on the outbreak of World War I, enlisted in a Bavarian regiment. Acting as a messenger between Regional and Company Headquarters on the Western front, he was wounded twice and received the Iron Cross for bravery in action. Germany’s defeat, and the humiliating conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, reinforced Hitler’s anti–Semitic and racist ideology, while strengthening his belief in the greatness of Germany and the virtue of war. In September 1919, Hitler joined and became the seventh member of the German Workers’ Party, a group founded by Anton Drexler (1884–1942) in order to promote a nationalist program to workers. By 1920 the party had changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis) and in July 1921, when Hitler became party chairman, its membership had increased to 3,000.

In November 1923 he made his first attempt to seize power when he tried to violently overthrow the Bavarian state government, in the Munich putsch, or bid for power. The attempt failed and Hitler received a five year jail sentence for treason.

Hitler contested the presidential election of April 1932, narrowly losing to the incumbent, Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934). However, the relentless growth of support for the Nazi party resulted in President Hindenburg appointing Hitler as chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. To national acclaim, Hitler pursued a policy of expanding German territory, an act which sparked the horrific death and destruction of World War II.

Throughout the war Hitler pursued his desire to build a “new order” in Europe, one that centered on the creation of a master Aryan race. Hitler’s Final Solution to rid the world of the Jewish population was an event of such incomprehensible horror and inhumanity that it has left the German nation a legacy that will haunt them for generations to come.

Although he remained popular with the masses, one group of army officers and civilians, under the guidance of Col. Claus von Stauffenberg (1907– 1944), attempted to assassinate Hitler in July 1944 but failed, and paid with their lives. By then, however, the Allied forces were closing in and Hitler, who was deteriorating both physically and mentally, acknowledged defeat but planned to reduce Germany to rubble for failing him. At this final hour his lieutenants turned against him and refused to carry out his orders. On April 30, 1945 Hitler and his wife of a few hours, Eva Braun (1912–1945), committed suicide in his Berlin bunker, their bodies then being taken into the Chancellery gardens and burned.

end of the German Weimar Republic, was reinforced in December 1933 with the passing of a further law, which declared the Nazi party “indissolubly joined to the state.” Hitler’s development of the Nazi state involved eliminating all working class and liberal democratic opposition, so he exploited the aftermath of the Reichstag fire not only for the suppression of the Communist and Social Democratic parties, but also for abolishing many constitutional and civil rights.

Thereafter, the Nazi party and the state became indistinguishable and Germany was under the control of a totalitarian regime. Party members who were of

“pure” German blood and were over eighteen years of age were required to swear allegiance to the Führer after which, according to Reich law, they became answerable for their actions only in special Nazi Party courts. At its peak, the Nazi Party had an estimated membership of seven million and although the majority had willingly joined, a great many more were forced to join against their will, including many civil servants who were required to become members.

As with Mussolini in Italy, Hitler’s powerful personal charisma, aided by his meticulously organized public appearances and the saturation of everyday life

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 0 3 |

F a s c i s m

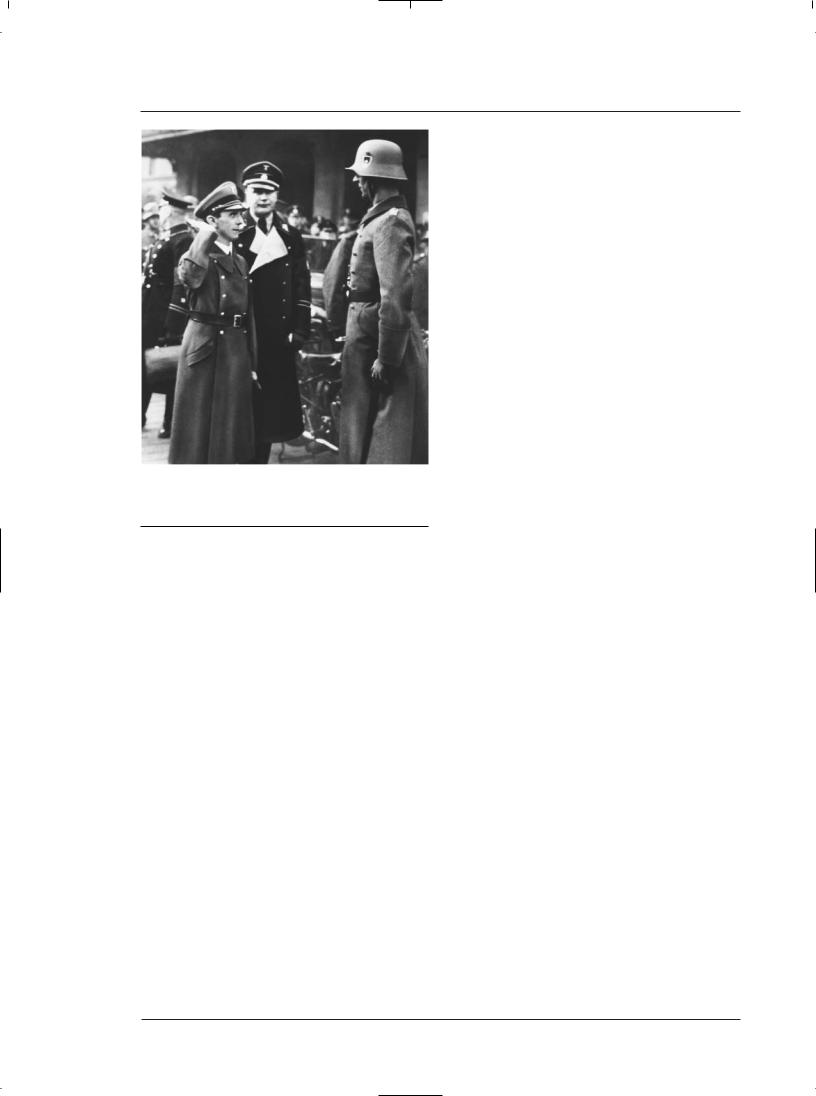

Joseph Goebbels, Propaganda Director for the Third Reich.

with Nazi symbols, posters, and indoctrination, established him as the infallible, hero–worshiped savior of the German people. Despite the fact that his repressive totalitarian regime had abolished many of their basic liberties, and that just about every area of their lives was pervaded and controlled by state police organizations, many of the German people responded with uncritical loyalty to their leader and a frightening willingness to obey all state–issued directives. The Nazification of German society was greatly assisted by the efforts of the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under the control of Joseph Goebbels, which was highly effective at promoting the Hitler regime as a “well–oiled Nazi machine,” by means of mass rallies, military parades, and sophisticated manipulation and censorship of the media.

That being said, the ordinary German citizen still lived a relatively normal life—as long as that ordinary citizen didn’t happen to be a Jew or a gypsy and did- n’t question the policies of the Nazi regime. Most people in Nazi Germany did not live in constant terror. Many had normal families, satisfying careers, and social lives closely resembling that of 1930s Americans. Author Walter Laqueur, in Fascism: Past, Present and Future, notes that people were “not told what games to play, what movies to watch, what ice cream to eat,

or where to spend their holidays.” In other words, a person could feel “free” as long as he kept his mouth shut and did not show much of an interest in politics. Conversely, if most people kept quiet and did not cause trouble, there was not really a need for the regime to risk agitating the populace by interfering in every aspect of life.

State agencies The principle auxiliary organization of the Nazi regime was the Brown Shirts or SA , often termed the “vanguard of National Socialism,” whose functions included the official training of the German youth in the ideology of National Socialism. The SA was also responsible for the organization of the Nazi program against the Jews in 1938, and throughout World War II they ensured the indoctrination of the German army and coordinated the Reich’s home defenses.

Another organization to prove crucial in maintaining state control was the SS, whose special combat divisions were invariably called upon to support the regular army in times of crisis. Assisted by the Sicherheitsdienst or SD, the espionage agency of the regime, the SS controlled the Nazi party in the latter years of the war, while the SD also operated the concentration camps for the victims of Nazi persecution. Other auxiliary agencies included the Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth organization) who prepared teenage boys for membership within the party, and the Auslandsorganisation (Foreign Organization) who promoted propaganda and the formation of Nazi organizations among Germans abroad. However, the most brutal and oppressive of all the state agencies was the infamous Geheime Staatspolizei (secret state police), known as the Gestapo, which was formed in 1933 to suppress all opposition to Hitler’s regime. Upon its official incorporation into the state, in 1936, the Gestapo was declared to be exempt from all legal restraints and was responsible only to its chief, Heinrich Himmler, and to Hitler.

By 1935 the last remnants of Germany’s democratic structure were replaced by the Nazi centralized state. The Reichstag no longer performed any legislative functions, but was retained to be used for ceremonial purposes, and the autonomy which provincial governments had previously exerted had been removed and replaced with local governments which were nothing more than strictly controlled instruments of central government. The process of coordination (Gleichschaltung) ensured that all private organizations, such as business, education, culture, and agriculture were also subject to party direction and control. Not even the church escaped the pervasive domination of Nazi doctrines.

1 0 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

Economy Upon taking control of the German economy, the most pressing problem to face the party leadership was unemployment, which at that time was in the region of six and a half million. Included in this figure were large numbers of Nazi party members who rapidly became disillusioned when Hitler failed to fulfill his anti–capitalist pledge to put an end to large businesses and cartels and to rejuvenate German industry by promoting the extensive growth in small businesses. The party rank and file demanded a “second revolution” and Hitler was faced with a choice between appeasing the working classes or forging an alliance with Germany’s industrialists. He decided on the latter course of action and, on the evening of June 30, 1934, which would come to be known as the Night of the Long Knives he issued orders for the SS to assassinate members of the SA, a group who had a mainly working–class membership and who Hitler now feared would attempt to threaten the social stability and agitate the Reichswehr (the regular army), with whom they sought a closer affiliation. A number of prominent SA members, including their leader Ernst Rohm (1887–1934), and over 400 of their followers were killed, most of whom had no intention of opposing Hitler.

Although it proved a powerful warning to other agitators, this ruthless display of state terror did not solve the underlying cause of the unrest, the problem of unemployment. To resolve this issue, Hitler had to regenerate German industry, and he proposed to accomplish this with the creation of the “new order.” In common with the Italian vision, the German “new order” was based on the premise of regenerating the Germany nation and restoring it to a position of strength and leadership in world politics, industry, and finance. In addition, Hitler sought it necessary to ensure that he possessed an adequate merchant fleet, and that he constructed modern air, rail and motor transport systems. To achieve total implementation of his plans required Hitler’s reversal of the economic and political restrictions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, which he was aware would ultimately result in war. Therefore the Nazi economy, by stockpiling raw materials and resources, and insulating itself from the international economy, was reorganized essentially as a war economy. Hitler’s reputation was enhanced when, in the years 1937 and 1938, the German economy made a dramatic recovery and the country achieved full employment, due mainly to the increasing level of rearmament, introduced in preparation for war, and to enable his policy of Lebensraum, which advocated the eastward expansion of German territory.

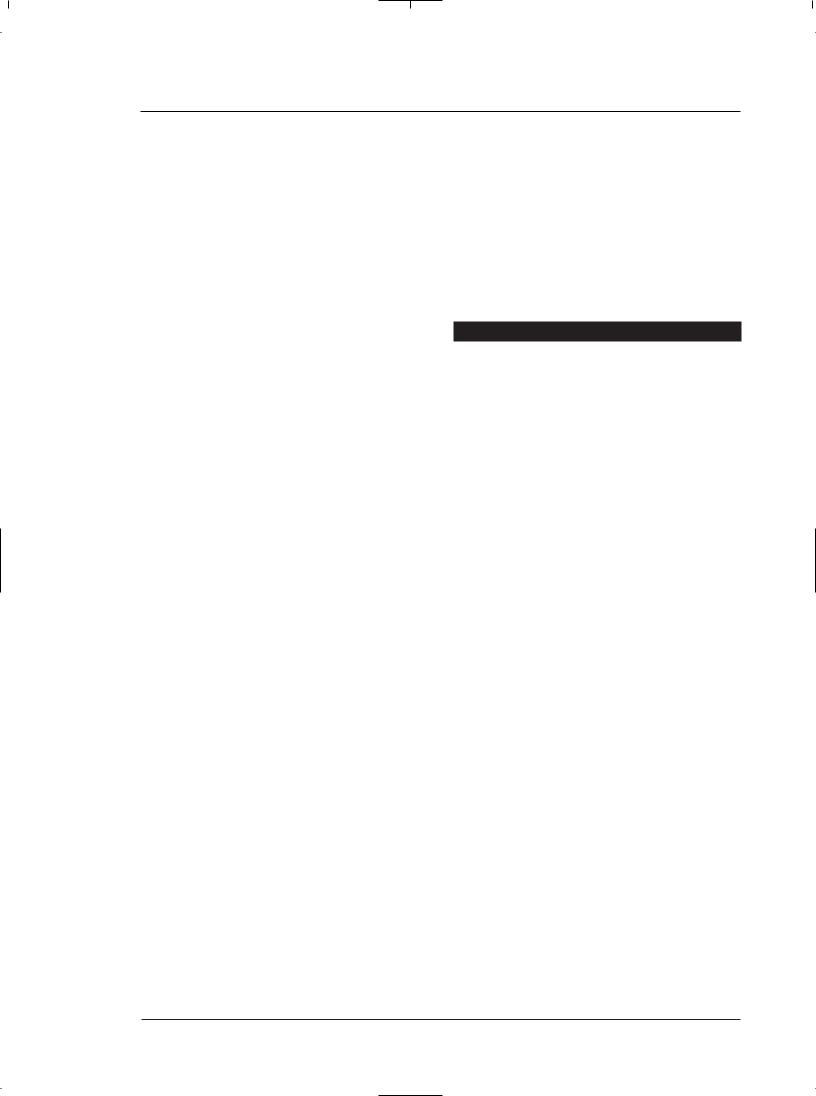

The creation of the new order also resulted in the banning of strikes, the abolition of trade unions

Adolf Hitler gives the Nazi salute. (United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum)

(including the confiscation of their assets), and the termination of all forms of collective bargaining between workers and their employer. In their place, a team of government officials, appointed by the Minister of National Economy, adjudicated on any issues relating to wages and conditions of employment. Official directives also empowered the Ministry of Economy to expand any existing cartels and introduce policies designed to merge entire industries into powerful conglomerates. Private property rights were preserved and previously nationalized companies were “re–privatized,” which returned them to private ownership but subjected the owners to rigid state controls. The introduction of these measures eliminated competition and ensured that the new order was economically dominated by four banks and a relatively small number of huge conglomerates. One of those to prosper was the notorious Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie

(I.G. Farben), an enormous consortium composed of over four hundred businesses, many of which exploited millions of prisoners of war and immigrants from conquered nations as slave labor. These cartels also readily supplied the materials and expertise that were employed in the systematic and scientific extermination of millions of innocent people under Nazism’s racial doctrines.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 0 5 |

F a s c i s m

Expansions and Expectations

Above all, Nazism was a nationalist movement, and Hitler’s plans for the Thousand Year Reich were based on the construction of a greater German state that would initially include Austria and the other Ger- man–speaking people who had been lost to Poland and Czechoslovakia in 1919, but would ultimately unite all of Europe’s Germans and rise to world supremacy. From 1933 to 1939, Hitler continually proclaimed that he was merely asserting the national rights of Germany, and most Germans agreed with his declaration that the imposed terms of the Treaty of Versailles had been a “shame and a disgrace.” Even those who despised the Nazi party methods, and much of its doctrine, supported its nationalist policies and acclaimed Hitler’s militarist program, which resulted in the reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936, the Anschluss or union with Austria in 1938 , the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and ultimately the start of World War II.

Genocide and Destruction of Lives

The most destructive aspect of German fascism was its racial and anti–Semitic doctrine. Drawing on the roots of German nationalism and anti–Semitism, which dated back to the nineteenth century, Hitler’s regime developed a hierarchy of “racial value” which was placed at the core of their vision of national rebirth and the creation of a “new order.” Human breeding programs were developed, called the Lebensborn experiment, in which SS members were used to sire Aryan (racially pure) children. Legislation was introduced which excluded Jews from the protection of German laws, and the Nuremberg Laws (1935) were passed, which withdrew citizenship from non–Aryans and forbade the marriage of Aryans to non–Aryans. Although several state–sponsored programs were implemented before 1939, such as the notorious Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) in November 1938, it was during the course of World War II that the Nazi regime displayed the full extent of its disregard for human rights and its capacity for murderous efficiency.

Although there is no evidence of a written order by Hitler authorizing the Holocaust, it is believed that he either issued a verbal order or, at the very least, made it clear to leading Nazis that this was his intention for the Final Solution. He did, however, officially endorse The Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseased Offspring which, by 1944, had enforced sterilization on over 400,000 women who were either mentally handicapped or considered at risk of passing on a hereditary illness. He also personally introduced a program of euthanasia which “put to sleep” more than 70,000 people, mostly children, who suffered from serious physical or mental disabilities. Of course, even

these atrocities were overshadowed by the policy of genocide which was pursued against all those considered “without value” by the Nazis. When the Allied forces finally brought the war to an end in 1945, the human cost of German fascism’s attempt to create a “new order” was the extermination of tens of millions of innocent lives and the infliction of terror and torture on countless others, while Europe had been reduced to rubble, and the political, economic, and geographical scars would remain for decades to come.

ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL RESPONSE

What perceptions and images come to mind when people consider the word fascism? Among the most common replies would probably be Hitler, the swastika, the Holocaust, inhumanity, and racism. These all appear to be perfectly rational and understandable reactions, based on what is known about fascist regimes, and their political, social, economic, and humanitarian ideology. Yet, understandable though they may be, these responses are wholly inaccurate, as what they affirm is the widespread confusion that has long existed between fascism and its notorious cohort, Nazism. The tendency to attribute the evils of Nazism to fascism in general paints a misleading picture of the values and motives of many fascist movements who denounced much of what Nazism advocated. It is important, therefore, when conducting an overall evaluation of fascism, that the abhorrent acts of inhumanity committed by Hitler’s regime do not affect the objectivity of the analysis.

Fascism as a political system was discredited and condemned after the Allied victory over the German and Italian regimes in 1945, and has since been unable to achieve any significant level of political power in its own right. However, considering its once dominant position, it is unsurprising that elements of fascist ideology have continued to exert a major influence in political movements and governments throughout the world. Yet, because of the lingering images of the human destruction and atrocities carried out in its name, these movements seek to avoid the label of “fascist” for fear of being perceived as guilty by association. This has resulted in neo–fascism and extreme nationalism devising far subtler and less apparent means of promoting their values and beliefs to a wider audience, in the hope of regaining a foothold on the ladder of political power. In order to identify and prevent any of these disguised strains of fascism from re–emerging from the shadows, it is important to construct a detailed understanding of its strengths and weaknesses, the conditions that are required for

1 0 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

its growth, and the techniques it employs to infiltrate society to attract support.

Fascism’s Limited Spread

Despite inspiring the development of countless groups and movements, fascism has only risen to power on two occasions, the Italian Fascists of Mussolini and Hitler’s Nazi party in Germany. Although it exerted varying degrees of influence in other countries, such as George Valois’ Le Faisceau in France and Oswald Mosley’s BUF in Britain, fascism consistently failed to convert this influence into significant political power. There were a number of reasons for fascism’s inability to successfully cast its net outside of the two Axis states, one of these factors being that, in the years between the First and the Second World Wars, Italy and Germany possessed the ideal combination of political, social, and economic conditions considered necessary for fascism to prosper, and their existing governments were too weak and unstable to provide effective resistance against the growing fascist bandwagon. In addition, the profound dissatisfaction with the apparent decline of their nation, and an intense fear of the threat posed by Communism had already established a desire, within the Italian and German public, for stronger and more nationalistic leadership.

In contrast, the fascist movements that arose in other European countries in the aftermath of World War I were denied the political space in which to develop, due to the long–established liberal traditions within these nations and the relative stability of their governments. However, before Nazism’s inhuman methods had caused fascism to become primarily associated with the atrocities of World War II, it was neither loathed nor condemned in those countries who had resisted it, but was accorded a certain degree of respect. Winston Churchill (1874–1965) is recorded as stating that, if he was Italian he would have been glad to be living under Mussolini’s Fascist regime. Even as late as the mid 1930s, many of Europe’s leaders continued to accept Italian Fascism as being a legitimate right wing reaction to Communism. Indeed, until Mussolini allowed Italian Fascism to become influenced by Hitler’s philosophy, the state was no more oppressive or violent than it had been under the liberal regime in the years leading up to 1922. It was those near–civil–war conditions that had led to the significant rise in Fascism’s support and enabled it to seize power from the previous government.

Also, at that time, Italian Fascism was strictly opposed to both anti–Semitism and biological racism, and even when Mussolini’s alliance with Hitler persuaded him to adopt these principles in 1938, the ma-

jority of his fascist regime and the Italian people rejected it, and on several occasions, the Italian military deliberately sabotaged the carrying out of anti–Jewish campaigns. During World War II the Italian General, Mario Roatta, disobeyed a German order to round up Jews because he viewed this as “incompatible with the honor of the Italian Army” which, in stark contrast to the German military, had pledged equality of treatment to all civilians.

These contradictions portray fascism as an extremely fluid ideology and one which enabled the modification of specific characteristics to accommodate the diverse nature of national traditions and values. Therefore, although all fascist movements asserted the importance of the nation, the need for strong authoritarian leadership, and the desire to create a “new order,” they frequently differed in regard to the methods they employed and the promises they made in order to attract support. Indoctrination and propaganda were other central tenets of fascist ideology, and these were also adapted to target each regime’s specific objectives. Italy tended to focus on promoting the “Italian national spirit” as being a tangible entity, relying on each individual’s support and effort for its survival and, in return, providing them with a sense of belonging and purpose. The majority of Italians did not view themselves as being governed by the state, to them it was a natural and integral organ of their existence, and in pledging their lives to pursue its success, they were willing to sacrifice their individualism. German fascism added a twist to this philosophy which, although in retrospect is viewed as evil and barbaric, at the time was an adaptation intended to reflect the German people’s cultural history of racism and anti–Semitism. For the German fascists it was not enough to simply become a unified nation with a greater standing within the world—they also focused their efforts on asserting German dominance within their own nation, through biological racism and ethnic persecution. This single modification of the classic fascist ideology led directly to the deaths of more than 30 million people. Although many fascist groups, who became generically termed the fifth column, assisted Nazism in these atrocities, a great many more opposed and condemned it just as strongly as those in liberal democracies.

Aims and Goals

The ultimate aim of fascism was to create a “new fascist man,” who would possess the desired strength and courage to earn the right to exist within a “new order.” A major element in the ideology behind this aim was the belief in the necessity and glorification of war, and it was this principle which ultimately led

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 0 7 |

F a s c i s m

to the defeat of Italy and Germany, thereby ending the era of fascism. In only twenty three years, from Mussolini’s seizing of power in 1922 until the Allied victory in 1945, fascism had indeed succeeded in reshaping society, though not with the outcome that they had intended. The reality that had been produced by fascist ideology included worldwide destruction, the senseless loss of millions of lives, the reduction of the major cities of Europe to rubble, and the permanent alteration of the political and geographical landscape of Europe. But what of the culpable nations? What had fascism achieved within its own countries that could justify the rest of humanity paying such a high price? The answer is...very little.

Economically, fascist countries did show some improvement as the government prepared for war. Many people came to compare the economies of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany to capitalist countries such as the United States, but this is inaccurate. There’s a big difference between a free–enterprise economy and one run by a government to achieve its own ends before those of its people.

Italy’s “national spirit” quickly disappeared, revealing a country which still possessed both class and regional divisions, while the introduction of corporatism had failed to shield the economy from the massive cost of the war effort. It had, however, left behind an improved relationship between politics and the papacy, the construction of the countries motor ways, and an increased level of self–sufficiency in food production. Under the Hitler regime, Nazism had succeeded in creating improved economic and social conditions for those groups in the upper levels of the racial hierarchy, but only at a huge humanitarian cost to the remainder of German society. As the full extent of the Nazi atrocities began to emerge in the aftermath of the war, the German people became the focus of the world’s hatred and condemnation. In his attempt to unite Germany and restore it to greatness and glory, Hitler and his regime had achieved the exact opposite and condemned his nation to years of control by their conquerors, during which time it became divided, both politically and geographically, for almost half a century.

There are, however, certain elements of the fascist style of government which have been incorporated into mainstream politics throughout the world. Every government and regime today acknowledge the importance of image in modern politics, and have developed the techniques used by Hitler and Mussolini to manipulate their audience. The carefully worded speeches, the stage–managed appearances, and the effective use of technology and the media have all been updated and employed with increasing sophistication. The majority of governments, even those in the ad-

vanced western democracies, favor a charismatic leader who will be considered an international statesman and the singularly authoritative spokesperson for his nation, and even the fascist’s use of symbolism and party slogans has gained widespread imitation.

Neo–fascism

Since 1945 no country has yet experienced a replica of the conditions which predisposed both Italy and Germany to the rise of fascism, but with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union have there has been a negative effect on the political stability of recent decades. In the 1990s there has been an increase in the support of neo–fascist movements and political parties with extreme nationalist agendas.The National Alliance led by Gianfranco Fini became part of an Italian coalition government, in France Jean–Marie Le Pen’s Front National regularly polls 20 percent in national elections, and the Austrian Freedom Party have amassed up to 28 percent of their country’s electoral vote. Other neo–fascist movements prefer to infiltrate established right–wing parties and exert their influence on immigration policy and on the increasingly popular platform of Euro–fascism, which advocates the strengthening of the European Union into a closely unified “super–state.”

Fascism has no concrete ideology, it has the ability to quickly adapt to changing circumstances to further its own aims. This capacity for improvisation assisted it to gain power in Italy and Germany, and it now allows neo–fascists and neo–Nazis to avoid the damaging associations of the past by disguising themselves in the cloak of the New Right and other mainstream havens of respectability. The need for political vigilance is succinctly stated in the words of Roger Eatwell: “Beware the men—and women—wearing smart Italian–style suits...the material is cut to fit the times, but the aim is still power.”

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•Compare the political ideology, style of government, and propaganda techniques employed by Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship in Iraq with those that exemplified Hitler’s Nazi regime before World War II.

•In 1945, Hitler and Mussolini both lost their lives in the final days of World War II, and after the Allied victory the fascist movements in Germany and Italy rapidly collapsed. Consider which of these two events, the loss of the war or the loss of their idolized dictators, was of greater signifi-

1 0 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

cance to the disintegration of fascism in those countries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Berwick, M. The Third Reich. London: Wayland Publishers, 1971.

Eatwell, R. Fascism: A History. London: Vintage, 1996.

Griffin, R. Fascism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Laqueur, Walter. Fascism: Past, Present and Future. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Thurlow, R. Fascism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Woolfe, S.J. European Fascism. London: Weidenfield and

Nicolson, 1981.

Further Readings

Adamson, W. Avant–Garde Florence: From Fascism to Modernism. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1993. A comprehensive study of the ideals and methods of the new nationalism.

Koon, T. Believe, Obey, Fight: Political Socialization of Youth in Fascist Italy 1922–43. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1985. Study of indoctrination and propaganda as used in education, sport, and other areas of interest.

Koonz, C. Mothers in the Fatherland. New York, 1976. A detailed and interesting account of life for women under the Nazi regime.

Lyttleton, A. The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy 1919–1929. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1997. A broad explanation of fascism’s formative years.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 0 9 |

OVERVIEW

Federalism divides sovereignty between a centralized state and regional or local states. This authority might be equal or hierarchical, shared or separate. Different republics, confederations, and unions have experimented with federalism across the years. The United States remains the most striking and enduring example of federalism; its system has changed radically as the relationship between state and national authority seeks to gain or regain balance.

HISTORY

The term federalism can be difficult to pin down. People discuss the federal government, but also talk the national, state, and local government. Which one is federal? At one point in the history of the United States, Federalists were those who supported the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. At another time, Federalists were members of a political party that advocated strong, centralized governmental authority. Some who were Federalists in the first case were not Federalists in the second. Add Anti–Federalists and definitions become more confusing.

The Earliest Years

Federalism dates to approximately 1200–1400 A.D., when the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Mohawks, and Cayugas ended their war and formed a fed-

Federalism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? Elected officials,

majority of power in national leaders

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Popular vote

of the majority

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Vote for

representatives

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The market

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The market

MAJOR FIGURES James Madison; Alexander Hamilton

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE United States

1 1 1