Political Theories for Students

.pdf

C o m m u n i s m

nized similarly to Soviet party organization. The Politburo governed the party, followed by the Central Committee.

In 1973, Kim began the Three Revolution Team Movement. His goal was to speed economic development and eliminate old ideas. He sent teams of young intellectuals to factories and businesses to guide them into modernity until 1975.

Kim continued to rule until his death on July 8, 1994. His son, Kim Jong II, became the next leader in North Korea. In the 1990s, many high officials left the country and the economy struggled. There were also serious food shortages. U.S. sanctions decreased when a summit between North and South Korea improved their relationship. North Korea is still communist.

ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL RESPONSE

Twentieth century communism has had disappointing results. The Soviet Union, her satellite states, China, Vietnam and East Germany have all gone through massive bloodshed in the name of communism. There are several speculations on why communism has met with so much trouble.

When the Bolsheviks came into power in the Soviet Union in 1917, the Soviets were weary from their tsarist history. They were poor, uneducated, and desperate for food. Their economy and industry was in the gutter and they were tired of losing their sons to war. Lenin pledged to change all of that, bringing goods to those who needed them and ending the war. He did get his country out of the war and he tried to create collective agriculture which provided for the country, but a shortage of resources meant that the little produce that existed was confiscated and given to his Red Army.

Many communist governments’ programs of forcing socialism or modernization on its people met with disastrous results. In China, Mao’s Great Leap Forward was a nightmare for many areas of society, particularly the education sector. The government interfered with teachers in the universities, and revolutionary ideals and nationalism replaced the standard curriculum.

Modern day China, with its economy thriving largely due to concessions to capitalism, is perhaps one of the strongest indictments against communism. Even the most dedicated Marxist would have a tough time arguing that the capitalist reforms of Deng haven’t been good for China. With continuing pressure from abroad regarding the government’s human rights poli-

cies and with Tiananmen Square still fresh in the minds of the people, many analysts feel Chinese communism won’t survive the twenty–first century.

And yet, there are many communist thinkers today who believe China is on the perfect Marxian path, that its economy was never truly socialist in Mao’s time, but rather an updated version of feudalism. With its introduction to capitalist reforms in the late twen- tieth–century, these communist thinkers say that China’s economy will become more capitalist until it has fully matured and will then make way for the true socialist revolution.

In the summer of 2001, Chinese President Jiang Zemin announced that the Communist Party would begin to accept private entrepreneurs as party members. However, even a small step toward democracy such as this probably had ulterior motives; it remains to be seen.

Another problem with communism could be the justification of the end by the means. Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and other leaders proclaimed a desire for communism that would provide equality and freedom for the people. In order to reach such a state, however, the leaders ignored equality and freedom. They forced compliance with their decrees and crushed anything in their path. Millions of people were killed in order to reach utopian socialism, which has yet to occur.

The violent tactics used by most communist leaders have created a worldwide distaste for communism. The word conjures up images of East Germany misery, of the Tiananmen Square uprising in 1989 when protesters were killed, and of Fidel Castro’s control of Cuba. Communism has seemed to come in tandem with dictatorship. This has meant a lasting dictatorship and an abuse of power rather than an ideal state which provides for everyone and exists without crime.

Marx felt that with marxism, crime would dissolve. He argued that criminals were driven to act because of their poverty and misery, but that with socialism there would be no such misery and, therefore, crime would dissipate. Rather than a lessening of crime, communism seemed to create a justification for heinous abuses of power. Because of dictatorships and forced compliance, leading members of the Communist parties were able to induce fear and acquire virtually anything they wanted. Their control allowed them to do as they pleased, and many of them did.

Marx also argued that the ruling class would only surrender after violence. Because of this, marxism and communism came to power after bloody struggles, both to overthrow the previous government and to convince the population of the need for communism. Violence is not the only option, however. All over

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

6 1 |

C o m m u n i s m

Europe, slavery was abolished on paper and the ruling class allowed the slaves to improve their positions without a violent fight. Perhaps the bloody beginnings of communism led to its bloody future.

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•What are the similarities between the versions of communism set down by Plato and Joseph Stalin? Are there more differences than there are commonalities? How would Plato feel about communism as it evolved over the centuries? How would Stalin feel about Plato’s Republic?

•Would Plato have been in favor of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution?

•Will communism survive in Cuba after Castro?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Binyon, Michael. Life in Russia, New York: Berkley Books, 1983.

Ebenstein, Alan, William Ebenstein, and Edwin Fogelman. Today’s Isms, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1985.

Feinberg, Barbara Silberdick. Marx and Marxism, New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

Hudson, G.F. Fifty Years of Communism: Theory and Practice, 1917–1967, New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, 1968.

Kort, Michael G. China Under Communism, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, 1994.

Kort, Michael G. Marxism In Power—The Rise and Fall of a Doctrine, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, 1993.

Laidler, Harry W. History of Socialism, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1968.

Martin, Joseph. A Guide to Marxism, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick. The Communist Manifesto, New York: Verso, 1998.

The Latin American Alliance, “Cuba.” Available at http://www.latinsynergy.org/cuba.html, 1997.

Further Readings

Barker, Ernst. Political Thought of Plato and Aristotle, New York: Holt, 1915. Gives a detailed analysis of the thought behind Plato’s works and those of his teacher, Aristotle.

Binyon, Michael. Life in Russia, New York: Berkeley Books, 1983. A journalist from the West chronicles Russian culture and the life of the ordinary Soviet citizen during his time in Moscow from 1978 to 1982.

Davies, John Llewellyn and Vaughan, David, translators. The Republic of Plato, New York: A.J. Burt Co., many editions. Plato’s idea of a utopia, and the first such example to be written down so extensively.

SEE ALSO

Marxism, Socialism, Totalitarianism

6 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

OVERVIEW

Conservatism is generally more reactive than proactive. It is more the presentation of collective responses to other principles and tenets than a collection of its own pure ideologies. Politically, opposing forces are most often called liberal, or favoring reform, and conservative, favoring the preservation of existing order or law and/or cautiously regarding proposals for change. Either term generally refers to an orientation toward facts, laws, policies, or events.

Conservative political tenets vary by country. Whereas socialism and fascism imply certain universal principles, conservatism promotes more parochial continuation. British conservative Lord Falkland once said, “When it is not necessary to change, then it is necessary not to change,” begetting the more common, “If it’s not broken, don’t try to fix it.” More moderate conservatives might cautiously change any practice or policy that seemingly has worked successfully for so long. In the alternative, conservatism supports returning to “traditional” or inherited political platforms and tenets as an argument for change.

But historical repetition itself defines what is considered “traditional.” Therefore, political conservatism can survive only where governments have been established long enough to secure social, economic, or political traditions. General characteristics include support for the “status quo”; cautiously considering or resisting change; and relying upon traditional values. Conservative ideology has been called “the right” or

Conservatism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? Elected officials, with

some appointed

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Popular vote

of the majority

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Vote for

representatives

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The owners

of capital

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The owners

of capital

MAJOR FIGURES Edmund Burke; Ronald Reagan

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE Great Britain in the 1980s

6 3

C o n s e r v a t i s m

CHRONOLOGY

1215: Magna Carta (The Great Charter) established under King John at Runnymede, England, giving birth to English political and civil liberties.

1787: “Great Compromise” at Constitutional Convention in 1787, establishes U.S. House of Representatives and Senate as representing national and federal principles, respectively.

1790: Edmund Burke’s “Reflections on the Revolution in France” forms the basis of conservatism.

1854: Republican Party, evolved from the Whigs, forms in the United States to oppose the Democratic Party.

1940: Winston Churchill becomes prime minister of Great Britain and will lead country through World War II.

1940s–1950s: “McCarthyism,” a period of intense conservatism in the United States marked by anti–Communist fears and criticism of liberal social policies, named after Senator Joseph McCarthy.

1955: The periodical National Review emerges, directed by Yale University graduate William F. Buckley, Jr., with anti–Communism, anti–feder- alism, individualism, and libertarianism its central issues.

1979: Margaret Thatcher of the Conservative Party, urging a reversal to Great Britain’s economic decline and a reduced role of government, becomes prime minister.

1980: Ronald Reagan, campaigning on such traditional themes as family and American pride, elected U.S. president and serves two terms.

2000: George W. Bush elected U.S. president.

“right–wing” segment of a theoretical political continuum which radical, reformative, and “liberal” elements define on the left.

Conservative or liberal inclinations are products of one’s educational, social, and political environment. Conservative or liberal bias in the media, educational institutions, the courts, and global affairs can greatly

affect daily life and one’s independent beliefs. One does not often hear about socialistic, communistic, fascist, collectivist, or totalitarian biases in schools or media. One may often hear, however, that conservative or liberal bias has affected a certain policy, rule, decision, vote, or presentation of facts. Under such polarization, there is a tendency to label all political ideas wanting reform or change in government as “liberal.” Conversely, any notion that supports continuing the controlling force or government is considered conservative, even if it means maintaining the status quo of an existing “liberal” government: Everything is relative. In any group of two or more persons discussing or arguing the merits of change, the voice of cautious resistance will be deemed conservative.

Historically, political conservatism in the United States has been most often associated with the Republican Party in an essentially bi–partisan system. On the other hand, and although other political parties have appeared sporadically, the Democratic Party has been most often identified with liberals wanting substantive government change to accommodate social needs. Labels, however, are deceptive. In an effort to capture more votes, political candidates have increasingly muddied partisan political waters. Thus, the constituency may often have to decide whether to elect an apparent liberal Republican or conservative Democrat. There are conservative liberals, liberal conservatives, progressive Republicans, and reactionary Democrats, so party labels often reflect political strategy more than ideology, generating more confusion.

U.S. President George W. Bush (1946– ), attempting to bridge political gaps, has extolled “compassionate conservatism.” In this century, partisan politics and “labels” may diminish as the U.S. attempts to establish parameters of conservative and liberal policies and principles.

HISTORY

Since conservatism generally does not involve strict adherence to tenets but rather the continuation of those in place, there is no tangible origin. Still, in every country in which government has existed long enough to establish social, economic, or political traditions, there will most likely be some form of conservative element in its legislative or executive ruling bodies, or in opposition. The emphasis here is on the Western Hemisphere.

Several world figures, such as Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), Cicero (106–143), Saint Augustine (354–430), Saint Thomas Aquinas (c. 1224–1274), Richard Hooker

6 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

(1554–1600), and John Locke (1632–1704), have pioneered conservative political thought. But Edmund Burke (1729–1797) is considered the founder of modern conservative thought. His “Reflections on the Revolution in France” (1790) form the basis of conservatism as a distinct political ideology. Burke’s form, however, has been, and remains, a Western phenomenon, and continues to defend most values of Western society. Thus, over the years, the United Kingdom and the United States have become the greatest proponents of conservatism, and even between these two great powers, conservative principles have differed substantially.

Great Britain

The United Kingdom consists of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; the first three constitute Great Britain. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire and the Norman invasion of England in 1066, the area was politically organized under the old feudal system, which entailed large–scale grants of land by William the Conqueror (c. 1027–1087) to his Norman followers. These followers were to become the dominant element of the country’s nobility. But the Anglo–Saxon influence contributed to the establishment of English political and civil liberties granted by the Magna Carta (The Great Charter) under King John (1167–1216) at Runnymede in 1215. As one provision in the Carta declared, “The barons shall elect twenty–five of their number to keep, and cause to be observed with all their might, the peace and liberties granted and confirmed to them by this charter.”

England’s Parliament is descended from the original councils of these barons, feudal landlords, and high–ranking clergy who advised the king on various matters. In the late thirteenth century, additional members of the Great Council were elected from town shires. A bicameral “Parliament” evolved, consisting of members appointed by the king (House of Lords), and elected tradesman, noblemen, guilders, educators, and merchants (House of Commons). From those councils and sessions came the differences in opinions that eventually led to further factions and parties within the House of Commons.

Great Britain’s Conservative Party traces to the founding of the Tory Party in 1689. Ironically, the term first applied to Irishmen who, dispossessed by the English in the mid–seventeenth century, became bandits. It then became, sequentially, a term for any marauder, an Irish Catholic royalist, and a supporter of James II (1633–1701). After 1689, it applied to any member of the English party that initially opposed the “Glorious Revolution” during which King James II was dethroned in a bloodless battle, and his daughter and son–in–law, William (1650–1702) and Mary

(1662–1694) of Holland, were invited to assume the throne. Thus, Tory resistance to this change in events may have contributed to their eventual association with conservatism. The Tories were to grow into the party that always supported the monarchy and opposed political reform. Their fear of having the French Revolution repeat itself in England directly relates to their conservative stance of upholding law and order. The Tory Party eventually split into Liberals and Traditionalists, losing their political hold to the Whigs for many years. The terms Tory Party and Conservative Party are often used interchangeably.

The Whigs, short for “Whigamore,” one of a body of seventtenth–century Scottish insurgents, were formed in the 18th century as opposition to the Tories. They favored high tariffs, more parliamentary control, and liberal interpretation of laws and charters. Britain’s Liberal Party is the heir to the old Whig Party. Following World War I (1914–1918), the Labour Party displaced the Liberal Party as the main opponent to Britain’s Conservative Party.

The Roots of Conservatism in America

In the United States, one must look to its founding fathers to understand American political theories, institutions, and moral order. Eventually, as an America independent of England began to form, so also did the rudiments of conservative versus liberal political thought, and their association with certain political parties. Party names and affiliations shifted, mostly the result of conflicting conservative and liberal opinions within.

In colonial America, anyone who could read was certain to have one book: the Bible. This unified New England pilgrims who may have otherwise differed. They established their commonwealth according to the Ten Commandments and it is fair to say that contemporary American democratic society rests upon inherited Puritan and Calvinistic influences. As Clinton Rossiter observed in Seedtime of the Republic: the Origin of the American Tradition of Political Liberty, from this Christian heritage comes “the contract and all its corollaries; the higher law as something more than a brooding omnipresence in the sky; the concept of the competent and responsible individual; certain key ingredients of economic individualism; the insistence on a citizenry educated to understand its rights and duties; and middle class virtues, that high plateau of moral stability on which, so Americans believe, successful democracy must always build.” The influence of New England Puritan Christianity and the work ethic of later immigrants from Western Europe were the underlying forces in establishing the rudiments of

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

6 5 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Edmund Burke

Noted politician, writer, and statesman Edmund Burke was the son of a Dublin attorney. He abandoned his own law studies in favor of literary work. After serving briefly as Secretary to the Marquis of Rockingham in 1765, Burke entered parliament as a Whig, a member of the people’s party. These were times of great upheaval, marked by coercion of the American colonies, and accompanying corruption, extravagance, and reaction. Burke, who greatly respected the wisdom of the ages, fought for liberty in his writings and speeches. But the key element in his early and best works was that liberty must relate to order. This required a sound, constitutional, and consistent statesmanship that enlarged the bounds of liberty only with caution. To him, a nation was a great living society, its constitution an exquisite balance of social forces, premised on complex relations and history interwoven with its institutions.

In the mid–1770s, Burke spoke against proposals to tax the American colonies and to regulate the government of Massachusetts. He did not dispute that the imperial government had the right to take such actions, but he did question the worthiness of such rights. To make his point, Burke delivered two impassioned speeches in the House of Commons: one dwelt on the matter of American taxation by duties and the other urged a reconciliation between the imperial Parliament and the colonies. When the American War for Independence did come, Burke opposed it; he perceived it a danger to the liberties of the colonies, and, therefore, of all English subjects.

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, was the most conspicuous development to coincide with Burke’s career. In 1790 he published Reflections on the French Revolution as a warning to fellow English subjects and admirers that the loss of monarchy and liberty could also occur in England, as it had in France, if preventive action was not taken. This most famous of his works went into an eleventh printing before the year ended and served to create an English response to the French Revolution.

Burke retired from political life soon after his son Richard died of consumption (tuberculosis) in August, 1794. In 1796, he opened a neighborhood school school for foreign and immigrant children who would not otherwise have been educated. Early the next year his health began to decline, and he died on July 9, 1797. Despite a move to have him interred, with public honors, in Westminster Abbey, Burke’s own will stipulated he be buried in the yard of the parish church of Beaconsfield.

Because the balance and tranquility of a great nation took so many years and so many components to achieve, Burke always argued against hasty change. He believed that only cautious and delicate adjustment to accommodate pressing events should be attempted, lest the unraveling of latent or unknown components that contributed to the whole would inadvertently cause its demise. Burke’s writings inspired many monarchs and leaders through their own confrontations with revolution or reform. His defense of preserving existing institutions and orders became the foundation for Western conservative thought.

the America’s capitalist democratic republic. It also served to influence the ordered liberty and principles found in the U.S. Constitution.

The Constitutional debates Yet, there were early political and cultural divides. This is apparent from the constitutional debates between the Federalists, who were essentially nationalists, and the Anti–Federalists, who rallied against strong central government in favor of state power. Both sides, however, were concerned with preserving liberty, having just fought a war to protect it. The Federalists believed there were enough checks and balances in the Constitution as written to

protect liberty. The Anti–Federalists wanted the Constitution to spell out specific liberties. Between 1787 and early 1788, five states (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut) had ratified the Constitution as written. Massachusetts was the first holdout. The Federalists penned a series of 85 papers composed for publication in New York newspapers under the title of “The Federalist,” hoping to sway public opinion. Of the papers’ three main authors, Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804), James Madison (1751–1836), and John Jay (1745–1829), Madison, in “The Federalist No. 10,” argued persuasively for a strong federal government. They said:

6 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States: a religious sect, may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the Confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national Councils against any danger from that source: a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the Union, than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular country or district, than an entire State.

But the Anti–Federalist Patrick Henry (1736–1799) of Virginia rebutted:

The first thing I have at heart is American liberty, the second thing is American Union. The rights of conscience, trial by jury, liberty of the press, all your immunities and franchises, all pretensions to human rights and privileges, are rendered insecure, if not lost, by this change so loudly talked of by some . . . You are not to inquire how your trade may be increased, nor how you are to become a great and powerful people, but how your liberties can be secured; for liberty ought to be the direct end of your Government.

The Bill of Rights The Anti–Federalists wanted a Bill of Rights written into the Constitution. Ultimately, the Federalists proposed ratifying the Constitution as written, with adding a Bill of Rights the first order. This compromise enabled Massachusetts and all other states, except Maryland, to ratify. The document took effect June 21, 1788, when New Hampshire became the ninth state.

George Washington (1732–1799) himself understood well the importance of his Anti–Federalist adversaries. He wrote,

Upon the whole, I doubt whether the opposition to the Constitution will not ultimately be productive of more good than evil; it has called forth, in its defence (sic), abilities which would not perhaps been otherwise exerted, that have thrown new light upon the science of Government, they have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion, and explained them in so clear and forcible a manner as cannot fail to make a lasting impression....

The Constitution of the United States of America had its first ten amendments, now commonly called the Bill of Rights. So much contention and debate had occurred among the States that Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), asked by a citizen what kind of government the Constitutional Convention had proposed for the country, replied, “A republic . . . if you can keep it.” America’s political system invites the free expression of opposing and diverse views, a right so fundamental that liberty would have little meaning without it. As Washington said in 1789, “The sacred

fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are . . . deeply and finally staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

Neither the Constitution nor its framers contemplated separate political parties as playing a role in the legislative process. Under the “Great Compromise” reached at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the delegates agreed that a House of Representatives would represent the “national principle,” while the Senate would be an expression of the “federal principle.” The Federalists had succeeded in having their proposed Constitution ratified, with the addition of the Bill of Rights; Washington was unanimously voted in as a non–partisan first president, and Federalist sentiments controlled the nation’s first Congress. John Adams, the second president, was a strong Federalist. But starting with Thomas Jefferson, the third president and an Anti–Federalist, many of America’s first presidents were “Democratic Republicans,” including James Madison and James Monroe after Jefferson. It was not until 1828 that the Democratic and Republican parties split into two under Andrew Jackson, who called himself a Democrat and the Federalist Party was dissolved.

Hamilton’s views Fundamental differences even ran through Washington’s cabinet, between Jefferson, the secretary of state, and Alexander Hamilton, the treasury secretary. Jefferson, an aristocratic Virginia planter and landowner, considered himself a progressive proponent of the “European Enlightenment“ movement and fully supported the French Revolution. He defended local government and viewed rural society as the bearer of democratic sentiment in a struggle against the commercial aristocracy of cities. Jefferson became increasingly conservative in his political sentiments, remaining essentially against centralized government and eventually, international commerce.

Hamilton, by contrast, admired the British constitution and staunchly opposed the French Revolution. The House as well as the Senate, upon receiving Hamilton’s first financial plan, began to exhibit a spirit of partisanship. Hamilton and his followers banded together as Federalists, and their opponents, representing agrarian (land–owning) aristocracy, led by Jefferson and Madison, became known as Democratic Republicans in 1792.

Hamilton and his followers, meanwhile, inspired the eventual creation of Henry Clay’s National Republicans and Whigs. Decades later, a formal Republican Party was formed from the Whigs in 1854 to

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

6 7 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

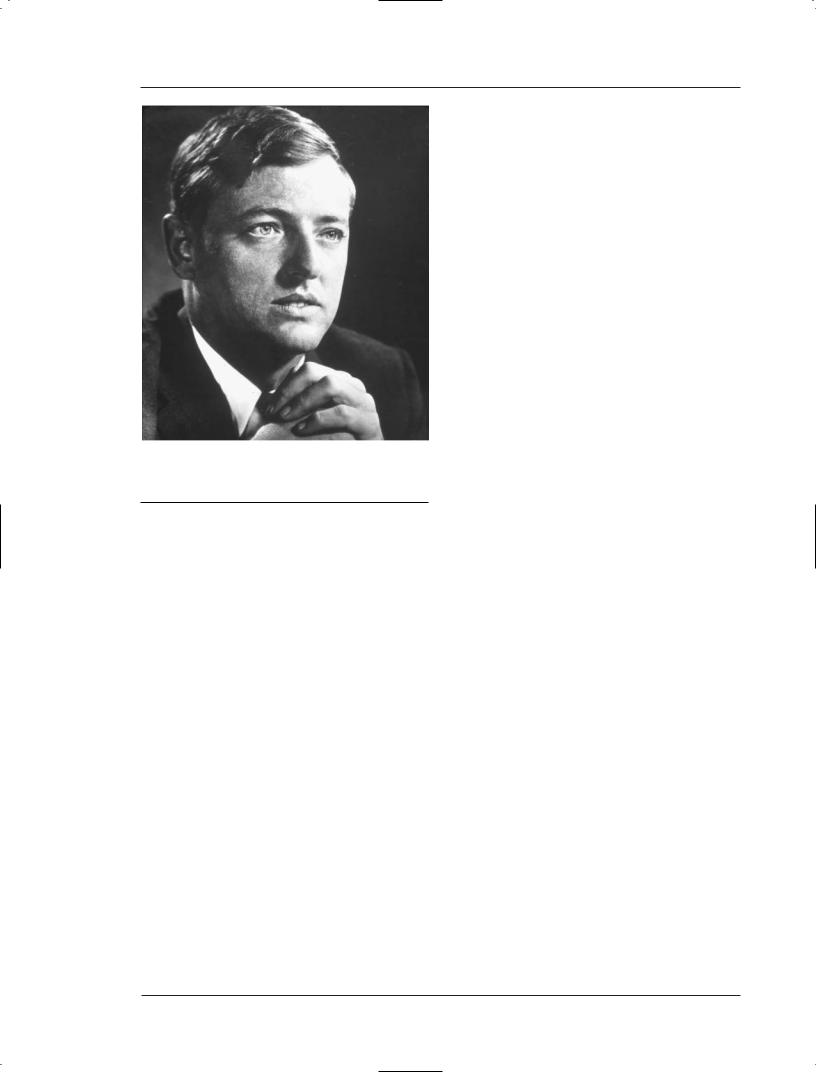

National Review editor William F. Buckley.

(Archive Photos, Inc.)

oppose the Democratic Party. This ended the American factions of Whigs and Tories, inherited from England. American Whigs supported the Revolution; American Tories opposed it. Since 1832, the Tories were considered the conservative party, and remained so in England (opposite the Whigs, and later, the Labour Party). In America, however, the Republicans (the prior Whigs) eventually became known for their conservatism.

Progressive movement Later in that century, a group calling themselves “populists,” or “People’s Party,” most prominently led by William Jennings Bryan, made Jefferson their hero, even though they advocated such policies as public ownership of utilities which would have horrified Jefferson. The Populist Party formed to represent agrarian interests in the presidential election of 1892. They advocated a more equitable distribution of wealth and power, big business and small independent businesses, a graduated federal income tax, and an increased currency with free coinage of gold and silver.

The Progressive Movement also aligned with Jeffersonian Populists, particularly in the Midwest and South. Jefferson had previously interpreted “Whig” to represent those in favor of change, and “Tory” to mean those opposed to change, that is, conservative. Those

supporting change do so in the name of progress, hence the term “progressive.” Throughout the late nineteenth century, the Progressive Movement fought for state ownership of railroads and utilities, hoping to break up monopolies and cartels hostile to rural farmers who relied on rail for shipment of their grains and produce. They also tended toward isolationism, non–interference in world affairs, and opposed imperialism on both moral and practical grounds. They promoted support for local government as a means to prevent wealth and political power from concentrating.

In the early twentieth century, however, the Populist and Progressive movements again splintered. A new progressivism, associated with Theodore Roosevelt and eventually Woodrow Wilson, was taking hold. This more liberal progressivism tracked similar events and times occurring during the Industrial Revolution in England. It promoted nationalism and imperialism, and saw American involvement in World War I as an opportunity to centralize economic control.

Later, during the lengthy period when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) controlled a Democratic administration, anti–New Deal conservatives and old–time Progressives united again in their opposition of World War II. They also wanted the repeal of the income tax amendment and passage of an amendment to prohibit deficit spending. The Roosevelt administration opposed them and attempted to rally support by labeling them German sympathizers and “Copperheads.” But the attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, nearly ended the argument for isolationism and the increasing threat of Communism sent the isolationists into decline. The only part of conservatism that continued after the New Deal and World War II was a suspicion of big government and big business. This thinking was eventually referred to as the post–war “Old Right.”

Conservatism After World War II

Still another shift occurred when Ohio Republican Senator Robert Taft (1889–1953) took over as the political leader of the Old Right. Taft was anti–Com- munist, favored free enterprise, and opposed most of New Deal social welfare legislation. Because the American conservative movement had changed ideologically so many times, the post–war Old Right stood out for its commitment to local liberties and local government, and a concerted dislike for the “collectivist” modern state. American conservatism of the 1940s and 1950s attracted big–business Republicans and other heirs of Alexander Hamilton, but was still under libertarian influence that opposed war, conscription, and imperialism.

6 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

From the turn of the century to the 1950s, there had been an increase in administrative consolidation. Government now controlled wages; the national civil service had grown tremendously; executive and congressional authority had empowered labor unions; and federal and state taxes had steadily increased to pay for all this. It appeared to conservatives that old– fashioned libertarianism had become endangered in its own country of origin. Big Government and Big Brother now ruled. The turn of events in post–war England was even more dramatic, when socialists swept to power in the summer of 1945. The newly elected Labour government entered Parliament and sung the “Red Flag” and other songs the revolutionary left had popularized starting in the 1930s.

Anti–Communism and opposition to Soviet imperialism became the driving forces of post–war conservatism. In 1955, the periodical National Review appeared. Directed by Yale University graduate William F. Buckley, Jr., the periodical’s central issues of anti–Communism, anti–federalism, individualism, and libertarianism were to shape American conservative politics during through the 1960s and beyond.

Post–war conservatism began during these years and coincided with the Cold War against the Communist Soviet Union. Clearly the galvanizing influence of this conservatism was American anti–Com- munism, generally called the “Red Scare.” President Harry Truman (1884–1972) used the Communist threat to justify his administration’s Marshall Plan, the European recovery program following World War II and an economic boost for American industry. Truman concurrently appeared before Congress to request extra funds to create congressional subcommittees to investigate and round up Communist insurgents within U.S. borders.

In a 1962 editorial for National Review, Buckley defended the House Committee on Un–American Activities and other congressional investigations by appealing to the notion of a “clear and present danger” to America were Communism left unchecked. Buckley balanced libertarian constitutional rights of freedom of speech with the threat of atom bombs and Marxist revolutionaries. Likewise, National Review writer Will Herberg, a Jewish theologian, wrote, “It is only when ‘un–American’ propaganda becomes a part of a conspiratorial movement allied with a foreign enemy, bent on the destruction of our nation, of freedom, and of Western civilization that it becomes a proper subject for congressional inquiry, disclosure, and legislation.” Thus, the influential Buckley and his colleagues actually helped promote the conservative premise of maintaining the free–enterprise system against the Communist threat.

Civil rights movement As the conservative movement entered the 1960s, it widened its focus and became more polarized against the growing civil rights movement. To diehard conservatives, the movement represented the destruction of communities that to date had been free of bureaucratic control. They resented government social engineering and considered it an abridgement of their private rights of contract and association.

But separating principle from policy created yet another splintering. There was internal dissent over civil rights, particularly feminism and what was seen as black radicalism. Orthodox libertarians also differed over strong laws regarding pornography. A “fusion” and alignment of issues occurred. Conservatism in America came to represent all of these: economic libertarianism, cultural traditionalism, strong local government, and militant anti–Communism. This fusionist concept united both libertarian and traditionalist factions and became the vital center of what came to be known as neo–conservatism.

This time marked the era of the new Campus Right as well. By the late 1950s, Yale had become a breeding ground such conservative activists as Buckley. In his first published book, God and Man at Yale (1952), Buckley protested the pervasive liberalism of Yale’s professors. Catholic universities such as Fordham, Notre Dame, and St. John’s in New York became important centers of conservative activity. The Catholic component of the intellectual right defended anti–Communist and anti–secularist views and promoted activism to stamp out these threats. They assumed strong positions of political and global involvement to save America Communism’s threatening spread. These views separated them, however, from the Southern and Midwestern Protestants, whose foreign policy views were still isolationist. The abortion controversy surfaced in the 1960s after mothers who had taken thalidomide drugs gave birth to deformed babies. Again, the Catholic and Protestant conservatives splintered over this issue, the Catholics being patently anti–abortion. Irish–American Catholics also rallied against liberal social policies such as forced busing. Racial tensions, court–ordered busing, and violent crimes during the 1960s started to move traditionally Democratic Catholic communities in the North toward the conservative Right. Concerned about the expanding welfare system, they demanded harder eligibility tests for welfare recipients.

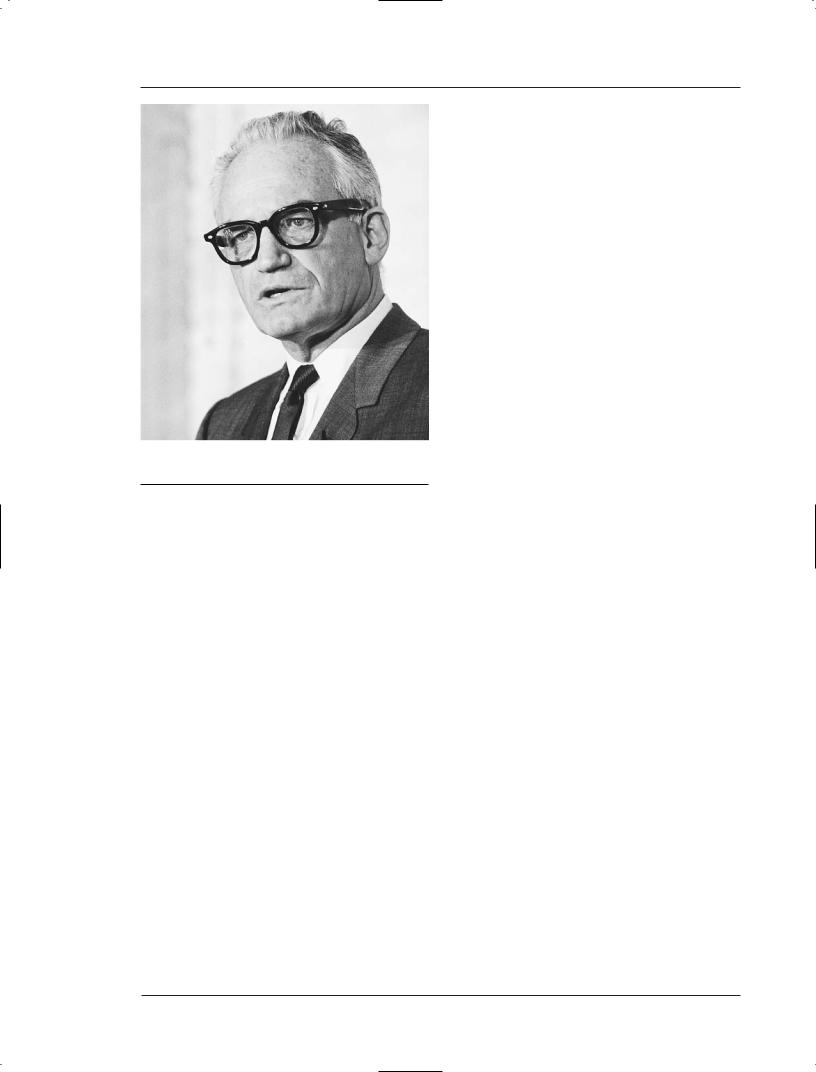

The conservative movement of the 1960s promoted economic deregulation, a strong military commitment, and a vigorous struggle against Soviet power. Republican Party presidential candidate Barry Goldwater’s (1909–1998) ultra–conservative platform

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

6 9 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

Barry Goldwater. (The Library of Congress)

included notions of a “breakdown of moral fiber in the United States,” a big–government conspiracy theory, and an ominous forecast of a Communist takeover of the country. Big business, nonetheless, withheld support from Goldwater–type purists, fearing the loss of lucrative contracts with an expanded federal government and civil service. In 1964, big business backed the more liberal Republican, Nelson Rockefeller (1908–1979). Goldwater won the Republican nomination that year, but lost the November election to incumbent Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973), who was completing the term of assassinated President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963). About this time, the Christian libertarian, Frank Meyer, who continued to prophesize until his death in 1972, warned that a conservative political majority would again rise in America when its citizens realized the harm liberal policies had caused to their constitutional and moral legacies.

The next political crisis was the Vietnam War, which also started in the mid–1960s. Involvement in the war had divided the nation, torn between conservative and liberal sentiments. A liberal Democrat had gotten the U.S. into the war, it was argued, so Republican President Richard M. Nixon (1913–1994) would end it. Nixon, however, resigned in 1974 during preliminary impeachment hearings following the Watergate scandal. The old conservative distrust of

big government returned, but this time, it involved one of their own.

The Reagan era For the 1980 presidential race, California Republican Governor Ronald W. Reagan (1911– ) was the conservatives’ dream candidate. As president, he was optimistic and humorous, his manner easy. Amid recession, he spoke of economic growth and hope. Reagan spoke firmly about containing Soviet and Communist expansionism. He was comfortable with his traditional views of family and American pride. He revived national pride and helped unite an economically troubled people. The economy during his administration (1981–1989) embarked on a twenty–year growth pattern that did not slow down until after the millennium, and big business supported him all the way. Conservatism was back in vogue.

Reagan, like Goldwater, spoke of a “moral crisis of our times,” and during his administration extreme right conservative organizations such as the “Moral Majority” surfaced. Ironically, for all the great things that Reagan did for the name “conservative,” the term became increasingly associated with the extreme religious right, a stereotype that also carried into the millennium.

Reagan’s rise also spawned different kind of populism, according to Richard Viguerie, publisher of

Conservative Digest. In a commentary for the National Review in 1984, Viguerie wrote, “To say that every populist is a demagogue is as wrong as accusing every conservative of racism,” he wrote. “The 1980s–style populists I describe in The Establishment vs. the People are anti–racist, compassionate, anti–Communist, future–oriented, and grounded in traditional values while sympathetic to libertarianism.”

George Herbert Walker Bush (1924– ), vice president under Reagan, was elected in 1988. Although there was no scandal associated with Bush’s term, liberal forces were brewing. Out of virtually nowhere came Arkansas Democratic Governor Bill Clinton (1946– ). From 1993 to 2001, Clinton occupied the White House during continued economic prosperity. Many of his liberal policies, however, such as admitting China into the World Trade Organization, drew fire from conservatives, and his intentions for a national health plan never materialized.

In the contested presidential election of 2000, Republican George W. Bush, son of the former president, defeated Clinton’s incumbent vice president, Al Gore (1948– ). Bush pledged to govern with “compassionate conservatism,” a call to return to the private sector, in voluntary social and faith–based set-

7 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |