Political Theories for Students

.pdf

F a s c i s m

as an official political party for two reasons. First, Italy’s recent political past had caused most Italians to become disillusioned with traditional party politics and the ineffectual parliaments that they consistently created. This persuaded Mussolini and the Central Committee to seek an alternative, less rigid, vehicle for their policies. Secondly, an unofficial and flexible nature of the organization had been able to attract disaffected members from other political persuasions, which allowed Mussolini to present Fascism as an inclusive and holistic political movement. With this achieved, and with the ras now threatening his position, Mussolini convened a meeting of the Fascist Constitutional Congress in Rome and, after some shrewd negotiations, successfully pushed through his plan to envelop the Fascist movement within an organized political party, the National Fascist Party (PNF). With Mussolini at the helm, the PNF rapidly attracted mass support from all sections of Italian society and, in particular, the armed forces. There was also an underlying sense of cooperation between the fascists and those in political authority, which led to many of the squadristi attacks on socialists going unpunished, even quietly applauded by those with business interests. This newly found acceptance of Fascism was further enhanced when the Prime Minister, Giovanni Giolitti (1842–1928), invited Mussolini and the PNF to join the nationalist electoral coalition, which allowed them to compete in the May 1921 General Election as a respectable, parliamentary–style party. As a result, the PNF won thirty–five seats in the Chamber of Deputies (Italian parliament), providing them with a great deal of political influence and, more importantly, the appearance of a constitutionally respectable political party. At the end of 1920 the Fascis di Combattimento and its associated fascist movements had a total membership of just over 20,000, but by December 1921 the PNF had boosted this to almost 250,000. After centuries of intellectual and political development, Fascist ideology had finally secured itself a stable, organized, and united political base; a powerful, charismatic, and politically astute leader; and an increasing body of electoral support comprising a cross section of society. For the first time, Fascism appeared to be on the threshold of political power.

Fascists Gain Control

Throughout 1922 Italy suffered continued political and economic instability, culminating in a general strike which threatened to cripple the Italian economy and invoke considerable public unrest. Mussolini seized on this as the opportunity to strike at the heart of the weak, divided government and secure Fascist

control of Italy. In a carefully prepared exhibition of strength and showmanship, Mussolini and the PNF threatened to overthrow the existing regime by dispatching Fascist squads to simultaneously occupy key sites and buildings in all the major cities, while Mussolini, at the head of 30,000 squadristi, led the “March on Rome.” However, on the morning of October 28, 1922, the date set for the threatened coup, King Victor Emmanuel III (1869–1947) struck a deal with the Fascists and, instead of his proposed march into Rome, Mussolini arrived at the royal palace by train on October 30, 1922 and was duly appointed the youngest prime minister in Italian history.

The Fascist regime that took control of Italy that day would remain in power for more than two decades, and throughout that time, as the regime sought to consolidate its authority and achieve its vision of a powerful, regenerated Italy, the underlying Fascist ideology underwent considerable evolution. Its vision of a new dawn, where the Fascist state would provide strong leadership, economic and social development, and a renewed sense of national pride was replaced by the nightmare of human tragedy and inhuman atrocities which were carried out in the name of fascism. When that evil chapter of history was finally brought to a close in 1945, Italy’s Fascist regime had been removed from power and Mussolini had, for a time, been installed as a Nazi puppet ruler in northern Italy, before being captured and shot by Italian partisans on April 28, 1945. In effect, Italian Fascism became a victim of its own success. The theories and achievements of the PNF between 1922 and 1936 became the model for subsequent fascist movements and Mussolini’s charismatic style inspired future Fascist leaders. Unfortunately, one of those movements was Nazism, and one of those leaders was Adolf Hitler (1889–1945), and due to a favorable combination of circumstances, fascism was able to assume a far greater degree of unchecked power and dominance in Germany than it had done in Italy.

Fascism’s Development in Germany

Although German fascism had been greatly influenced by its Italian counterpart, its origins and development were firmly rooted in German history. The aftereffects of World War I were particularly embarrassing for a nation with such a proud military past as Germany, especially the humiliating conditions imposed on them by the Treaty of Versailles. In addition, post–war problems such as massive unemployment and crippling inflation placed the ruling Weimar Republic under increasing pressure from both left and right. The political opposition to the democratic leadership was comprised of two totalitarian parties, the

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

9 1 |

F a s c i s m

MAJOR WRITINGS:

Mein Kampf

Adolf Hitler composed Mein Kampf (My Struggle) while in Landsberg Prison for his part in the unsuccessful attempt to seize power from the Weimar government in 1923. Later to become the bible of Nazism, and a major influence on fascist movements everywhere, Mein Kampf was a powerful compilation of fascist theory, propaganda techniques, racist thought, and plans for the creation of the Third Reich, which Hitler declared would first conquer Germany and then Europe as it embarked upon its one–thou- sand–year reign.

Originally titled Four and a Half Years of Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice, Mein Kampf was not “written” in the conventional sense, but was dictated by Hitler to his fellow inmate and confidante, Rudolph Hess (1894–1987). In his book, Hitler declared the racial superiority of the German people, warned of the threat posed by the Jews, communists, and liberalism, and explained the need for a strong, authoritarian state which was willing to use war to achieve military and economic greatness for Germany. It outlines, in great detail, his belief in Aryan supremacy, anti–Semitism and the importance of conquering those who do not recognize their racial inferiority to the German race. Mein Kampf also specified the military conquests that Hitler would later attempt in order to expand the German nation and described the fates of those who were conquered.

Published in 1925, Mein Kampf initially attracted little interest from the public, due in part to its length and the labored style of its writing. However, upon Hitler’s ascension to Chancellor, and ultimately Führer, its popularity soared and millions of copies were sold. Although rarely read from cover to cover, the majority of German households possessed a copy of Mein Kampf, as did followers of fascism everywhere, and the influence it exerted is evidenced by the devastating events that followed.

Communist party and the misleadingly named National Socialist German Workers’ Party, more commonly known as the Nazi Party. Far from being socialist, Nazism encapsulated, in theory and in practice, the most extreme of fascist doctrines, with an ideology based upon oppression, racism, violence, and inhumanity.

By 1923, the economic and social crisis in Germany had virtually destroyed the authority of the democratic Weimar government and, on November 8, the Nazis organized an unsuccessful attempt to gain power. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, the Nazis and 600 armed storm troopers raided a Munich beer hall, in which several leading government figures were addressing a public meeting. However, the Nazis’ military and popular support was insufficient to succeed with their coup d’etat and, following a violent clash with armed police, Hitler was arrested and subsequently sentenced to five years in prison. He served only nine months in Landsberg Prison, and it was during this time that Hitler formulated and dictated his book Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”). Upon his release from Landsberg, Hitler discovered that economic conditions had improved, resulting in an increased air of confidence in the democratic leadership and a sharp decline in popular support for fascism. Hitler and his associates, presumably heeding the lesson learned in Munich, acknowledged that the time was not right and quietly set about rebuilding and reorganizing the party. It was not until the national election of 1930 that they achieved any notable electoral victories, their cause aided by Germany having almost been brought to its knees by the economic crisis and crippling unemployment that resulted from the Depression that swept over Europe and the United States.

In the years between 1925 and 1929 Hitler reinforced his position as the Führer, or irrefutable leader, of the Nazi party and continued to develop the radical fascist doctrine which would shape the Third Reich. Hitler held dictatorial power over the party and set about creating a paramilitary wing, known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), drawing recruits from the unemployed, criminals, and down–and–outs of Bavaria. This period also witnessed important changes in the functions of the Schutzstaffel (SS) who were originally formed to act as bodyguards for Hitler but, under the guidance of Heinrich Himmler (1900–1945) assumed responsibility for supervising and policing the party, and for ensuring that Hitler’s patriotic propaganda was able to permeate every area of German society with little resistance. It was becoming apparent that German fascism intended to control all aspects of national life, yet its proposals to restore Germany’s economic and military pride proved extremely popular with the

9 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

electorate, and seemed to instill the nation with a renewed sense of purpose. Therefore, when economic disaster struck again following the Depression, and the democratic Weimar Republic was unable to resolve the crisis, it was the Nazi Party’s stable, unified appearance, its commitment to German rebirth, and its powerfully charismatic leader, which helped them become Europe’s second fascist government. Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933, and the Third Reich began its twelve–year reign of terror and oppression, during which time its “achievements” included plunging Europe into a war which cost over thirty million lives.

The Third Reich, which had been created to reign for a thousand years, effectively ended with the suicide of its Führer on April 30, 1945 in Berlin, with the victorious Soviet troops only streets away. The triumph of the Allies in World War II and the deaths of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini effectively brought the era of fascist rule to a close. In an attempt to eradicate the memory of fascism in Europe, and to ensure that it could not rise from the rubble, the Allies banned Fascism in Italy and set up a program of de–Nazification and re–education for the German people. Fascism had to be seen to be punished, and in addition to the Nuremberg Trials of 1946, which imposed death sentences or incarceration on many of the surviving Nazi leaders across Europe, there was a desire for retribution, resulting in tens of thousands of fascists and fascist sympathizers being summarily executed. Germany, having come so close to conquering the rest of Europe, stood defeated and helpless as it was divided into the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) under the control of the Soviet Union, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) which was initially controlled by the western Allies of Britain, France, and the United States. It would remain a divided nation, tainted by the shadow of Nazism, until its celebrated reunification in 1990.

Fascism In Other Countries

Outside of Germany and Italy, fascism was unable to convert its significant influence and public support into political power. Many regimes and movements were denied the political space in which to fully develop their fascist ideas, but did incorporate specific aspects of fascist theory into their doctrines, with varying degrees of success. Yet again it was the aftereffects of World War I, coupled with the rise to power of Mussolini and Hitler, that encouraged many of these movements to emerge and develop during the 1920s and 1930s. In Spain the fascist Falange Party, founded in 1933 by Ramiro Ledesma Ramos (1905–1936), wielded sufficient influence to become incorporated

into General Francisco Franco’s (1892–1975) regime, which emerged victorious from the Spanish Civil War in 1939. The Falange was later subordinated to Franco who, although the dictator of a brutal and totalitarian state which ruled until 1975, is more accurately described as being an authoritarian conservative rather than fascist. France had always possessed a strong sense of nationalism, so it came as no surprise that many fascist movements evolved from the extreme right of French politics. However, unlike Italy and Germany, French fascists formed and supported several movements, rather than focusing their energy and ideas into promoting a single, united fascist party. As a result, groups such as Le Faisceau (“The Fasces”), the Francistes, and the Croix de Feu (“Cross of Fire”) (which was banned in the same year as its formation only to be reformed as the Parti Social Francais) each separately attracted a great deal of political and popular support, but no individual movement was able to amass a power base capable of threatening the political establishment. British fascism, in the form of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), was viewed as a novelty by the public, and posed no threat to the liberal democratic traditions. After its formation in 1932, the BUF and its founder Sir Oswald Mosley (1896–1980) attracted significant publicity, but a government ban on the wearing of paramilitary uniforms was enough to ensure the BUF’s collapse. Despite differing in many respects, the movements that evolved in Spain, France, and Britain shared an ideology that mimicked that of Italian Fascism and sought to bring about change through the use of nationalist and militarist policy. However, in eastern and southern Europe, the path of fascist thought was following the route taken by Nazism, with the emphasis on racism and anti–Semitism.

The Iron Guard was a violent fascist movement in Romania that developed and promoted its ultra–na- tionalist and anti–Semitic beliefs from 1930 until its destruction by the Romanian army in 1944. In Hungary, the nationalist dictator Miklos Horthy de Nagybanya (1868–1957) ruled from 1920 and, when the country came under German control in 1944, the reins of power were handed to the radical fascist Arrow Cross Party, albeit only briefly. From 1932 onwards, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970) established a dictatorial regime in Portugal, into which he incorporated many fascist characteristics such as the one–party state, a secret police force, and widespread propaganda. However, the virulent anti–fascist period that followed the defeat of Germany and Italy in 1945, and the disclosure of the atrocities that had been carried out in the name of fascism, ensured that any party or movement holding a similar ideology came to be

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

9 3 |

F a s c i s m

viewed with a mixture of loathing, fear and suspicion. Even those regimes who remained in power after the war, such as in Spain and Portugal, diffused their fascist traits and adopted a style more akin to authoritarianism than totalitarianism. It appeared that fascism had not only been discredited, but any movement acquiring the label of “fascist” became instinctively despised and relegated to an existence on the most extreme of political fringes.

Political Landscapes Change

The socioeconomic recovery after 1945 removed many of the conditions that had been such a major factor in the rise and advance of fascism, and the consensus among historians was that fascism had simply been a phenomenon of the inter–war years, a case of a political movement being in the right place at the right time. What no one could foresee was the rapidity with which the world’s political landscape would change. Within a few years of their united triumph, the wartime Allies became absorbed in their own ideological battle, the Cold War, and the eradication of fascism was no longer their priority. The superpowers’ preoccupation with each other allowed fascists the political space to regroup, develop new ideas and strategies, and emerge as a significant influence in many European countries. The first instance of this re–emergence, known as neo–fascism, occurred as early as December 1946, when former members of Mussolini’s regime developed the Italian Social Movement (MSI) which, in the 1948 general election, secured six seats in the Chamber of Deputies. At around the same time, in Germany, the link with fascism was maintained, firstly by the Socialist Reich Party (SRP), and then by the National Democratic Party (NDP) which continued to promote its extreme nationalistic views into the 1980s. In recent years many neo–fascist movements have infiltrated extreme right–wing groups in an effort to gain wider support and increased influence. Front National, under the leadership of Jean–Marie Le Pen (1929–), executed this tactic so successfully that they established themselves as a legitimate third party in French politics, obtaining widespread support for their fascist program, in particular their anti–immigration policy. In Italy, Gianfranco Fini (1951–) guided the National Alliance (AN) into a coalition government in 1994 and two years later Fini had become Italy’s most popular politician. This trend in the upsurge of neo– fascism has been mirrored in many countries, as witnessed by a widespread increase in extreme nationalist groups and racial violence against ethnic minorities, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Although racism and fascism are not synonymous, many of

these movements do possess a core fascist ideology, based on promoting national identity and pride, and on singling out racial scapegoats for any social and economic difficulties. To reach its political pinnacle, the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini required the political and economic instability that arrived in the wake of World War I, and unnerving comparisons may be made with the horrifying policy of “ethnic cleansing” that was carried out following the collapse of the former Yugoslavia throughout the 1990s. Fascism, as an identifiable political theory, has existed for less than a century, yet the violence, murder, and brutality for which it is already held directly responsible make it essential that close study is made of its causes and its future development. In the words of Primo Levi (1919–1987), a writer, chemist, and survivor of Auschwitz, from his work, If This Is a Man: “We cannot understand it, but we can and must understand from where it springs, and we must be on our guard. If understanding is impossible, knowing is imperative, because what happened could happen again.”

THEORY IN DEPTH

Although strands of fascist ideology had been evolving throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was the First World War and the destruction left in its wake, that proved to be the active catalyst that fused these fragmented ideas into a coherent and powerful political theory. In most countries this emerging philosophy was confined to several extreme nationalist movements, which existed on the political fringes, and in a few others it exerted varying degrees of limited influence within major political parties. However, within a handful of countries, where socio–economic crisis was combined with strongly held national traditions, disillusionment with the existing leadership, and the emergence of an inspirational figurehead, the core components of fascist ideology were adopted to develop a radical and powerful political system. The unrestricted power enjoyed by fascist regimes, and the illiberal policies they introduced, while ultimately remembered for the mass atrocities to which they led, also reshaped their societies, resulting in the majority of their citizens enduring an everyday life which came to be dominated by oppression, fear, and violence. However, such was the appeal of the fascist philosophy and propaganda that, in Germany and Italy in particular, the majority of people were willing to sacrifice their individual freedoms and ambitions for the greater good of their nation.

9 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

Nationalism

The ability to convince each individual that the nation belonged to them, and that they in turn belonged to the nation, was one of the doctrines which lay at the heart of the fascist political system. In fact, it could be argued that this is the central tenet of fascist ideology. Fascist philosophy is anti–liberal, in that it views the nation as the most important political and social unit, and that the individual’s value is measured only by the extent to which he contributes towards the well–being and success of the national community. In all fascist writings and speeches, the recurrent message is one of national rejuvenation, rebirth, or regeneration, and it is this belief in organicism—that a nation is an entity in its own right, an organism that can decay or be revitalized—that instilled in a nation’s people a sense of duty to protect and nurture their nation, irrespective of the cost to themselves. This “illiberal nationalism” exploited the basic human desire to conform and belong, and provided individuals with a sense of importance and purpose, believing that they would be the generation that would restore the nation to its rightful place of prominence and glory. This type of nationalism breeds powerful emotions and feelings of kinship between those who view themselves as being ethnically and culturally united in their endeavors, but inevitably generates equally intense feelings of hostility and distrust towards those considered as outsiders. Therefore, racism was an inherent factor of fascist ideology, and although this did not necessarily have to result in the persecution of specific groups or races, unfortunately, that is exactly what happened in the countries where fascism was able to gain political control. In Germany, the Nazis systematically victimized and murdered countless Jews, Gypsies, blacks, homosexuals, and anyone who did not conform to the fascist regime’s definition of “ethnically pure” was subjected to abuse, oppression, and violence, not only from the authorities, but also from within the community, including their neighbors, work colleagues, and even those whom they had considered as friends. In Italy the Fascist regime conducted a less extreme campaign of propaganda and violence aimed, more generally, at persuading all immigrants and foreigners to return to their own nations.

The extreme nationalism contained in fascist ideology was at the core of its main aim, that of creating a “new order.” This was the term used by fascists to describe their vision of how they would implement their doctrines and values in order to transform society. Regardless of how the theory and practice of fascism varied from regime to regime, and from country to country, the total commitment to establishing some form of “new order.” was inherent to all. The typical

fascist view, most notably implemented within Italy, was that the creation of the new order, and the new Fascist man which it would cultivate, should be an inclusive process, instilling into as many of its citizens as possible strong feelings of national pride and a desire to work together towards restoring their nation to a position of greatness. Unfortunately, both for its own people and for the world at large, the Nazi regime took a very different approach towards creating the “new” Germany, and enforced programs and policies that went far beyond the basic fascist premise of asserting national virtues, traditions, and superiority.

Nazism

The Nazi model of fascism was contaminated by a pseudo–scientific component, developed from the theory of Social Darwinism, which was used to promote and justify its overtly racist, anti–Semitic, and morally reprehensible policies. Although Charles Darwin’s (1809–1882) principle of “survival of the fittest” had long been a recurrent theme in fascist theory, the Nazi regime replaced natural selection with their own criteria for deciding who was, or was not, fit to survive within their “new order.” Society in fascist Germany therefore became multi–layered, with the regime and its agencies at the pinnacle, followed closely by all individuals who were considered to be racially pure (that is, Aryan) and who enjoyed the social and financial rewards which this status bestowed. However, for those who were placed lower down this discriminatory hierarchy there was no inclusion into the proud national community, only the misery of continual oppression, persecution, and terror. The most appalling and barbaric treatment was reserved for those unfortunates who found themselves in the lowest classification and whom, not only the fascist regime but also many of the German people, considered to be sub–human. This ill–fated group, including Jews, Gypsies, and the mentally handicapped, among others, were so despised that they were commonly labeled “the useless eaters.” By use of indoctrination, which was an another important facet of all fascist movements, this depersonalization of the nation’s “internal enemies” was accepted by the public who, either through fear or through consensus, condoned the systematic abuse, torture, and murder of countless innocents, whose only crime was to differ racially, culturally, or physically from the fascist blueprint of the “new man.”

Bringing About a “New Order”

In order to successfully implement the societal changes necessary for the creation of a “new order,” fascism relied heavily on its commitment to a strong,

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

9 5 |

F a s c i s m

authoritarian state and to the widespread use of indoctrination and propaganda. Both of these factors were mutually advantageous, the propaganda helping to ensure the continued dominance of the totalitarian regime, which in turn applied its absolute control over the lives of individuals to maximize the effectiveness of the indoctrination. Fascism has often been accused of containing more style than substance, yet its mastery of propaganda techniques and its skill in the art of political theater provided it with a greater mandate for the implementation of its policies than most other ideologies could ever hope for. The techniques employed by fascism, to ensure public conformity and to inspire enthusiasm for the creation of a “new order,” were highly sophisticated, both in their conception and their execution.

Drawing on psychological theories, such as Gustave Le Bon’s (1841–1931) study of crowd behavior, and the primitive, but highly persuasive, effects of symbolism and tradition, fascism was able to convert vast numbers of people to its ideals and values without having to present a rational and coherent body of ideas. Instead, it spawned charismatic leaders who commanded total obedience and assumed grandiose titles, such as Führer and Il Duce, thereby acquiring an air of infallibility. To cultivate this sense of hero–worship towards its leadership, fascism was responsible for the introduction into politics of stage–managed public appearances and carefully written speeches which contained powerfully emotive slogans and “catchphrases” designed to reinforce national unity and support for the state, while imploring every individual to offer greater sacrifice and effort in the struggle to achieve a “new order.” The success of this approach was assisted by programs of indoctrination, which permeated every section of society through the education system, youth groups, the workplace, the frequent public mass rallies, and the extensive presence of fascist symbolism. State control of the media provided fascism with yet another valuable method of exerting its influence, and it made full use of the opportunity by transmitting powerful propaganda films and radio shows, and ensuring strict pro–fascist censorship of the press. From dawn until dusk, those who lived under the power of fascism found that every activity involved in their daily life was, in some way, influenced or controlled by fascist ideology and policies. Many willingly welcomed this as being necessary for the eventual success of their nation, while others, who were less committed to the values of the regime or the concept of a “new order,” accepted it, though rather less eagerly.

Then there were those who were not persuaded by the propaganda, and refused to accept fascist au-

thoritarianism, whether on political, moral, or racial grounds, and opposed it, either openly or within their private circles. Fascism, however, was eventually well prepared for this with state controlled secret police and an extensive network of official and unofficial informants enabling it to suppress most incidents of opposition by means of fear and violence. The secret police organizations, such as the SS and the Gestapo in Germany, had full access to an individual’s private life, and they were quick to assault, imprison, or even murder, anyone who dared to denounce the regime or its leadership. It was a fearful and lonely existence for those who opposed fascism and for those not considered worthy of inclusion into the “new order,” as most citizens supported and obeyed the leadership and would readily report any acts of disobedience or denunciation. There were frequent instances of teachers informing on their students and traders reporting on their customers, but what illustrated the immense control that fascism exerted over its subjects was the distressing number of dissenters who were reported by friends, neighbors, and, in some cases, their own families. This coercion proved successful in suppressing a great deal of the resistance to fascist policies, although it also made it impossible to accurately assess the levels of dissent that existed. Did the majority of German and Italian people genuinely support their fascist regimes, as some commentators profess, or were they merely reluctant to oppose it for fear of the terrifying consequences?

Eliminating Opposition

Fascism’s commitment to eliminating all opposition was only one manifestation of its intense hostility towards all forms of liberalism. The fascist state was a rejection of all that liberal democracy stands for, and involved the abolition of the principles of pluralism, individualism, parliamentary democracy, and the concept of natural rights. The centralized, single– party state was the foundation on which fascism sought to rebuild the “new order” and, within this reorganized society, there was no place for opposition parties or democratic elections. All other political parties were banned, and in the case of the Communists and Socialists, many of their members were imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Fascism had long held a deep–rooted hatred and fear of communism, as exemplified by this comment, made by Heinrich Himmler, the man who led the SS, during a lecture to his officers in 1937: “We must be clear about the fact that Bolshevism is the organization of sub–humanity, is the absolute underpinning of Jewish rule, is the absolute opposite of everything worthwhile, valuable and dear to an Aryan nation.” Yet, without commu-

9 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

nism, it is unlikely that fascism would ever have gained political power in either Germany or Italy, as it was the fear of the threatened spread of Bolshevism from post–revolutionary Russia, westward into Europe, that increased the electoral support for fascist movements. Many people believed that fascism’s strong authoritarian and militarist approach was their nation’s prime hope of protection. The electorate were proved correct and fascism emphatically extinguished any threat posed by those on the political left, and continued this violent persecution throughout the duration of their dominance. Yet, beneath the intense hostility, fascism and Communism shared a common ideological enemy—Capitalism—and it was this opposition to both Communism and Capitalism that has seen fascism sometimes referred to as the “Third Way.”

Third Way

This “Third Way” was most apparent in the economic thought and policies of fascist regimes which, although exhibiting slight variations, tended to follow a similar model, that of corporatism. Unlike Marxist theory, fascism did not concur with the belief that class antagonism was the primary agent of social change, neither did it agree with the capitalist emphasis on economic motives as the basis of a nation’s success. Fascist theory sought to eliminate class conflict and bring about social change by creating a national unity based on the shared values of language, culture, race, and tradition, and by glorifying traits such as heroism, bravery, and strength, rather than materialism. It allowed the ownership of private property, and developed its economic policy along the lines of a partnership between the owners, the workers and the state, through the setting up of syndicates and corporations. In practice the workers interests were given low priority and they received little support from their unions, which had become state–run organizations following the abolition of all free trade unions, while the employers were rewarded with the granting of state investment and government contracts. Notwithstanding this unsuccessful attempt at corporatism, fascism possessed no stable or coherent economic policy, but instead relied on a series of temporary, short–term measures, while state intervention continued to escalate, as fascist economies increasingly relied on the work provided by their rearmament policies. War, therefore, was not only an important political and ideological factor of fascism, but was also crucial economically.

In economic matters, as in many others, fascism displayed its tendency towards male chauvinism. With the ideology’s emphasis on war, strength, and heroism, it followed that women were relegated to the role of home–maker and mother of the nation’s future

workers and warriors. Germany, in particular, adopted an extremely repressive attitude towards women, excluding them from all leading positions within the party and prohibiting them from becoming judges or public prosecutors. After 1933, the regime extended these restrictions and dismissed many married female doctors, teachers, and civil servants to concentrate on, what Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945) described in 1934 as “the task of being beautiful and bringing children into the world.”

Militarism

Militarism and fascism are often considered to be synonymous, which is unsurprising considering the events and atrocities for which their unholy alliance will forever be remembered. To fascists, military strength and victory in battle lay at the very core of their personal and national identity. It encapsulated the ideals and virtues which they glorified above all others, and would ultimately, in their opinion, lead to the successful creation of an heroic “new order.” Only through war, against internal and external “enemies,” could fascism assert its core values and ensure continued public support as it strove to achieve its ideological goals. All fascists agreed with Mussolini’s view that war was inevitable and often preferable, and believed that the annexation of weaker nations by the strong, to form powerful empires, was the highest form of human development. In addition, the military values of patriotism, unity, and discipline could equally be applied to fascism, and military symbolism was widespread in fascist societies. By putting them into uniform and involving them in organized movements, fascism gave individuals a sense of belonging, and reinforced the belief in a national cause that was of far greater importance than their individual lives.

Fascist foreign policy, therefore, tended to be extremely aggressive, driven by the desire to expand their territory and assert the superiority of their nation. In Italy, where Mussolini was aware that his army had serious weaknesses, they used shows of military strength as a means of manipulating public opinion, whereas the German fascists possessed the capability and the conviction to expand their “new order” throughout Europe, and were ruthless in pursuit of their goal. The consequence of this determination to create a great and glorious Germanic empire was the attempted genocide of the Jewish race, a barbaric program of ethnic cleansing and racial war, and the brutal butchery of over 30 million soldiers and civilians in World War II. That fascism came so close to succeeding in its mission is terrifying to contemplate, especially when considering that this destruction was only the first phase in the blueprint of the “new

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

9 7 |

F a s c i s m

order.” Subsequent plans for fascist domination included the deportation of millions of Slavs to Siberia to provide the German people with increased Lebensraum (living space), and the extension of the fascist model of Social Darwinism to include the areas of health and social welfare, the level of assistance to be determined on the grounds of race and fitness. Although the Allied victory in 1945 successfully halted these developments, the extent of public acceptance and support for such abhorrent policies served to illustrate the ever–present danger of underestimating the influence and appeal of fascist theory.

Although the end of World War II saw the defeat of fascism’s political power and the widespread condemnation of its illiberal and racial theories, it has continued to exist as a political undercurrent, as numerous groups have modernized and adapted its ideology in an effort to revive its popularity. Unlike the movements of the inter–war years, neo–fascism and neo–Nazism has to compete with a relatively stable, liberal democratic Europe, not one that is in political and economic crisis. So, although the fundamental ideology remains the same as it was before 1945, neo–fas- cists have had to repackage their ideas and promote them in a far subtler manner than their predecessors. This often involves the infiltration of mainstream political parties and movements, especially those on the extreme right, where they attempt to introduce their nationalist and racial values into areas such as anti–im- migration policy and the issue of asylum seekers. Fascism has become a marginalized and fragmented movement, which has, in general, lay dormant since its military defeat in the Second World War, but as the campaign of ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s illustrates, if given the correct political or economic stage, fascism will be waiting in the wings.

THEORY IN ACTION

The failure of many democratic governments to effectively tackle the political, social, and economic consequences of World War I, the Great Depression, and the perceived threat from the spread of communism fueled the creation and development of fascist movements throughout the world. The Falange Espanola in Spain, the Iron Guard in Romania, and the Arrow Cross Party in Hungary all shared many of the fascist doctrines and displayed much of its political style. In one of Europe’s most well established and advanced democracies, that of France, it was estimated that, in 1934, almost 370,000 people were members of the various French fascist movements and, in

Britain, support for Oswald Mosley’s BUF was sufficient to bring about a government ban on the wearing of paramilitary uniforms. Yet, despite this widespread influence and depth of support, fascist ideology only managed to manifest itself in the form of a truly fascist government in two countries, Italy and Germany, and the era of its dominance would last only twenty–three years.

Fascist Italy

The “March on Rome” in October 1922 was a demonstration rather than a glorious bid for power, but it resulted in King Emmanuel III inviting Mussolini and his party to form the world’s first Fascist government. It was a relatively smooth takeover and, due to the limitations on their power invoked by a coalition government, the Fascists made very few changes to the Italian state in the first three years. Upon becoming prime minister, Mussolini successfully secured a parliamentary vote allowing him to rule by decree for a year. It was during this time that he established the Fascist Grand Council, a forum with the official function of coordinating the activities of the party and the government, but which Mussolini intended to eventually supercede the parliament as the center of power. The gradual move towards absolute control continued with the introduction in 1923 of the Acerbo Law which granted two–thirds of parliamentary seats to any party that obtained a majority of the vote in a general election providing they had polled at least 25 percent of the total votes. Mussolini and the PNF duly obtained control of two–thirds of parliament at the next general election, in April 1924 and, with Fascist membership having spiraled from 300,000 in 1922 to 783,000 by the time of the general election, the initial limitations to Fascist power were disappearing. Having already outlawed the Communist Party, immediately after taking office in 1922, Mussolini then abolished what little remained of the socialists and trade unions after their crushing electoral defeat, before introducing further measures designed to increase the authority of the PNF within the parliament, and to strengthen his position as Il Duce.

The year 1925 witnessed the creation of two major agencies of state control. First of all, Mussolini, in order to maintain control over the blackshirted squadristi, incorporated them into the Fascist Voluntary National Militia (MVSM), a paramilitary force whose main function was the violent oppression of left–wing opposition, but who also assisted in the theater of Fascist politics by performing in ceremonial events. Shortly afterward, in response to several assassination attempts on his life, Mussolini created a state–controlled secret police force, the OVRA, who

9 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Benito Mussolini

The founder and leader (Il Duce) of Italian Fascism, Mussolini was born in Predappio, Romagna, on June 29, 1883, the son of Alessandra, a blacksmith, and Rosa, a schoolteacher. Following in his father’s footsteps, Mussolini joined the Socialist party in 1900 then entered his mother’s profession by qualifying as a schoolmaster in 1901. In 1910 he became secretary of the local Socialist party in Forli, and his reputation as a prominent socialist was further enhanced the following year when he was jailed for his opposition to the war that Italy had declared on Turkey. Upon his release, Mussolini was appointed editor of Avanti!, the Socialist newspaper based in Milan, establishing him as one of Italy’s leading socialist activists.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Mussolini denounced it as “imperialist” and argued for Italian neutrality, even threatening to lead a proletarian revolution if the Italian government took the decision to fight. Within a few months, however, he had totally reversed his position, and called for Italian intervention on the side of the Allies, resulting in his expulsion from the Socialist party. On November 15, 1914 he founded his own newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia (The People of Italy), in which he expounded his support for the war, and introduced the embryonic ideology of the Fascist movement.

He formed the Fasci di Combattimento in March 1919 and, with the support of industrialists and

landowners who saw him as their protection against communism, he entered the Chamber of Deputies in 1921. Following the fascists’ symbolic “March on Rome,” King Victor Emmanuel III, invited Mussolini and his now formalized Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista), to form a government on October 30, 1922. Mussolini had become the youngest prime minister in Italian history and quickly became the most powerful.

He linked Italy to Nazi Germany with the Rome–Berlin Axis in 1936, closely followed by the “Pact of Steel” in 1939, and committed the military of Italy to the Nazi war effort in 1940. After many Italian defeats, a meeting of the Grand Fascist Council was called on July 25, 1943, and Mussolini’s colleagues turned against him. King Victor Emmanuel III first dismissed him from power, then had him arrested.

Rescued by German parachutists in September 1943, Mussolini set up a puppet regime, under the control of Nazi Germany, in the Republic of Salo in northern Italy, where he “ruled” until April 1945. As the Allies approached Milan, Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, attempted to flee into Switzerland, but were discovered at a roadblock near Lake Como. On April 28, 1945, Mussolini was shot by his Italian partisan captors, and his body was strung up publicly in Milan.

were responsible for monitoring Italian society for evidence of dissenters, who were then tried by the Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State. Although this illustrated the repressive nature of the Fascist state, the vast majority of dissidents were sentenced to exile, with relatively few being incarcerated and even less condemned to death. Unlike the Nazi regime which would later gain power in Germany, the development of the centralized fascist state in Italy was based more on acceptance than it was on fear and, except in the case of left–wing political opposition, there remained a degree of toleration of criticism and dissent.

By 1930, most of the political opposition had stood down or been abolished, and Italy had become a single–party state, with Mussolini at the helm. To fortify his position as Il Duce, Mussolini granted ad-

ditional powers to the Fascist Grand Council, and any members of the PNF who were perceived as a threat were removed and replaced by impressionable sycophants. However, throughout his reign, Mussolini’s authority over the state was limited by the country’s economic weakness, his reliance on the backing of the king and his political advisers, and the need for continual compromise with the existing establishment. Although he overcame these constraints in creating a dictatorship, he was never able to achieve the level of absolute power and control which was later to be enjoyed by Hitler in Germany. To ensure his continued supremacy, and to advance the implementation of Fascist policies, Mussolini therefore had to rely more on the force of persuasion than on the power of coercion. In his development of propaganda techniques and

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

9 9 |

F a s c i s m

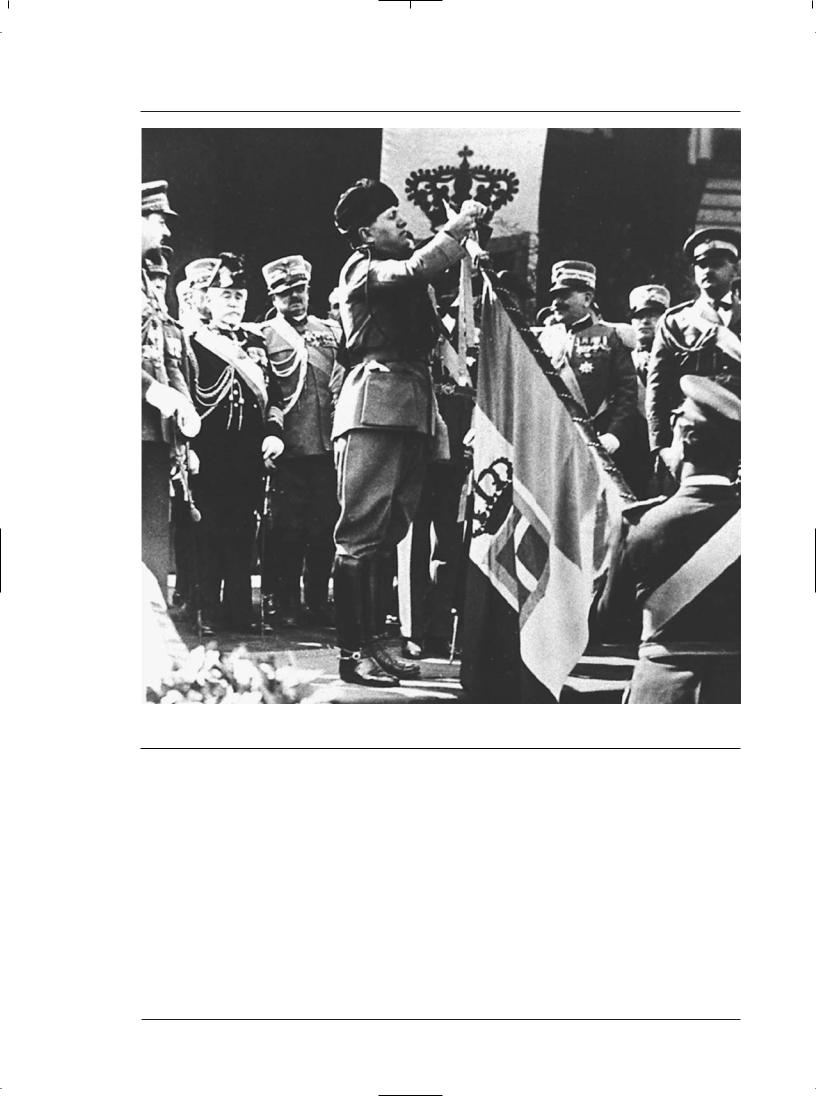

Benito Mussolini decorates the battle flag of the Royal Air Corps. (The Library of Congress)

political theater, Mussolini created what was to become a familiar pattern for subsequent dictatorships, elements of which have evolved to become incorporated and accepted into most areas of modern mainstream politics.

Il Duce

An extremely charismatic leader who was highly skilled in the use of propaganda, Mussolini ran most of the important government offices himself and made use of any opportunity to reinforce his revered public image. Such was the importance he placed on public persuasion and manipulation that, in 1935, he set up an official governmental ministry for the promotion

and development of propaganda. Influenced by Gustave Le Bon’s theories of crowd psychology and Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844–1900) belief in the “will to power” and the Ubermensch (overman or superman), Mussolini displayed a charismatic style and dynamism that proved a convincing advertisement for his rejuvenation of Italy. Mass rallies, orchestrated military displays, the renaming of Labor Day to Birth of Rome Day, and the resetting of 1922 to Anno Primo (Year One) all instilled the Italian people with the belief that their nation was destined to return to the glorious days of the Roman Empire.

On a smaller but no less significant scale, Mussolini placed great emphasis on his personal image in

1 0 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |