Political Theories for Students

.pdf

C o n s e r v a t i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Ronald Reagan

Conservative presidents may come and go, but President Ronald Reagan was responsible for such terms as “the Reagan Revolution’’ and “Reaganomics.” Although liberals in the media used these terms pejoratively, the extended period of economic growth and stability that followed his presidency gave credence to his principles and empowered a revitalized conservative constituency in America.

Born in 1911 in Tampico, Illinois, Reagan won a scholarship to Eureka College, where he majored in economics. He was president of his student body, played football, and was captain of the swimming team. After graduation, Reagan became a radio sports announcer in the Midwest and eventually moved to film acting. In over a quarter of a century of acting, Reagan played in more than fifty films and served as a television host. As president of Hollywood’s Screen Actors Guild, he became embroiled in disputes during the McCarthy years over communism in the film industry, and his political views shifted from liberal to conservative. He tried to purge suspected Communists from the movie industry and took a strong anti–Communist stand when testifying before the House Committee on Un–American Activities. Promoting American conservatism around the country, Reagan was elected California governor in 1966 by a winning margin of nearly a million votes.

In 1980 Reagan was elected president, winning 51 percent of the public vote and a ten–to–one margin in the Electoral College. He was perceived as a

forceful leader who called for a return to patriotism and traditional morality, and who would restore prosperity to an economically ailing nation. After taking office, Reagan made good on his promises to cut back on big government and taxes, strengthen national defense, curb inflation, overhaul the income tax code (1986) and stimulate economic growth. He shepherded the 1981 Economic Recovery Act. His “supply–side” economics policy intended to stimulate citizen spending on goods and services with money saved from reduced taxes. At the end of his administration, America was enjoying its longest recorded period of peacetime prosperity without recession or depression. Reagan’s administration, however, was marred by the “Iran–Contra” affair, a political scandal involving secret weapon sales to Iran in return for support in freeing U.S. hostages held by Lebanese terrorists friendly to Iran. Ostensibly, the moneys earned from the weapon sales were diverted to Contras fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Reagan denied any knowledge of these secret activities.

When he left office in 1989, opinion polls confirmed Reagan as one of the most popular presidents of the twentieth century. However, when a recession hit the United States in 1991, many critics blamed the policies of Reaganomics in the 1980s. In 1994, Reagan announced that he was battling Alzheimer’s disease, and by doing so brought much attention to the illness.

ging conservatism that has been left behind. For example, the British public, through the media, expressed its wish for a more personable and approachable monarchy, especially during the time immediately following the death of Princess Diana (1961–1997). Conversely, a majority of the British public confirmed its continued belief in the monarchy, its heritage and tradition, and its maintenance as a British institution.

In economic policy, the general conservative attitude toward a laissez–faire capitalism or free enterprise system has always been under attack by a concerted minority. The problem has been that both conservatives and liberals support such a system, and the dissenting minority is also comprised of both con-

servative and liberal elements of political following. This mingling with the opposition has manifested on other fronts as well—on issues such as abortion, affirmative action, foreign policy, social welfare, and taxation.

The New Right

Historians and partisan politics have attempted to rectify these muddles by creating subgroups and attaching newer names to the ideology, such as “neo–conservatism,” “American conservatism,” “the New Conservatism,” and “the New Right.” However, each of these terms ultimately relates to a particular historic period when the tenets of political conser-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

8 1 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

vatism were again being re–defined by, and re–oriented to, pressing issues of the time. For example, critics have argued that following the fall of Communism in the Soviet Union (a declared victory for conservatism), there was no cause celebre to unite conservative forces anymore. But to twenty–first century American conservatives, high crime rates and financial returns on investments were of greater concern than Communism. The fall of the Soviet Union was remote and not palpable, perhaps of more interest to their aging parents than to them.

Moreover, although conservatives have historically been referred to as the political “right,” this can no longer be true because those that want to maintain the status quo actually oppose radical “neo liberals” who want to establish a world–wide system of lais- sez–faire capitalism. Still further, some conservatives actually support and defend certain institutions of a welfare state. The distinction between conservative and liberal views must now necessarily be made on an issue–by–issue basis. General stereotypes and labels have become increasingly less accurate, and characteristic parameters of conservative ideology continue to shift.

This, in turn, pressures political parties in a bipartisan or multi–partisan political system to more clearly distinguish themselves from their competitors or opposition, which, in turn, creates a more adversarial campaign and election system. In a government such as that enjoyed in the U.S., free speech allows two or more sides of an issue to be freely argued, though with special–interest lobbying. But the system has checks and balances. A conservative or liberal president has veto power over Congress, and Congress can override a presidential veto. Judicial rulings of constitutional provisions ensure that no radical new law abridges the rights of the people.

The National Motto

Perhaps a poignant example of the ebb and flow of conservative versus liberal forces in the United States is the sometimes anecdotal, sometimes vociferous arguments over the country’s motto. In 1956, the U.S. Congress enacted a law declaring the national motto of the United States to be “In God We Trust.” Although the motto had existed de facto for more than one hundred and fifty years prior, it had never been officially codified into law. The motto is now codified at 36 U.S.C. 302. In fact, America’s history is replete with other references to God and Providence, only some of which have come under such attack.

Our country, undeniably, was formed on Christian principles. For about two hundred years, this cre-

ated no palpable problem, as the majority of Americans were primarily of Western European Christian heritage. Any protest directed at the symbol or motto of America would have been unthinkable. But the great immigration influx of the twentieth century has made America more consisting of multiple cultures, races, and peoples. Conservatives would argue that it does not matter where you came from, that now you are an American, and you must live according to American tradition and heritage. Liberals would argue that the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution require that America accommodate the cultural heritages of its newcomers and minorities, who may find such references to God as contrary or even repulsive to their own beliefs. But the real bitterness centered on a majority of Americans still identifying with Christianity in the twentieth century, and resenting a small but vociferous minority attempting to usurp their American heritage. The tensions created when applying old traditions to a newer multi–ethnic, multi–cultural population are all too apparent.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never expressly ruled on the constitutionality of our national motto. When asked to rule, however, it has let stand the decisions of several U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal (one level down from the Supreme Court) that have upheld the constitutionality of the motto, essentially on grounds of historical significance and heritage.

Still, on April 25, 2000, a three–member panel of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit ruled 2–1 that the official motto of the State of Ohio, “With God All Things Are Possible,” was unconstitutional. The motto, which was unanimously adopted by the state in 1959 (Ohio Revised Code Section 5.06), existed for years without ado, along with the state wildflower, the state animal, the state coat of arms, and the state song. However, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), representing a single plaintiff, Reverend Matthew Peterson, had challenged the motto in 1997.

Extreme conservatism can be as harmful as radical liberalism. Unbending or uncompromising attitudes, whether conservative or liberal, have limited appeal in any society. It has been partly a media phenomenon that has been responsible for creating stereotypes of conservative Americans as ultra– right–wing religious fanatics. In reality, that is as far from the truth as promoting the perception that all liberals are revolutionaries who wish to agitate Americans toward socialistic totalitarianism. Both extremes do not speak for the vast majority of Americans (and politicians) who vacillate along a continuum of association according to their own views and beliefs.

8 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•Both conservative and liberal governments have enjoyed extended periods of economic wealth and prosperity. In the United States, both Republican and Democratic parties have produced successful administrations. During such times, dissention between conservatives and liberals has often been exaggerated or instigated only to accommodate the need to polarize political platforms. Nothing in the U.S. Constitution either requires or suggests the need for partisan politics. How is it, then, that partisan politics have come to be inextricably bound to the American political system?

•Semantics have always played a role in defining conservative or liberal leanings. The media has the power to create, enhance, or otherwise influence the popularity or unpopularity of certain political views. For example, it may draw more attention to a political view by referring to it as “leftist” rather than “liberal.” It may choose to refer to those favoring abortion as “family planners,” and abortion clinics as “family planning clinics.” In recent times, the mere insertion of the word “Christian” immediately connoted an affiliation with “the right.” The public may view something according to how impartially facts have been presented. There have been previous demands by the public for more unbiased news coverage and a demand that “equal time” or “equal press’’ be given for the presentation of opposing views.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

“Bicentennial of the United States Constitution.” Printed by the Office of the Special Consultant to the Secretary of the Army. 1989.Reprinted in part from The People Consent: Revisiting the Ratification of the United States Constitution. Courtesy of Edith R. Wilson & J. Goldman. New York: 1987.

“Biography of Ronald Reagan.” 2000. Available at http:// www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/rr40.html.

“Biographies: The Political Philosopher, Edmund Burke (1729–97).” Available at http://www.blupete.com/Literature/ Biographies/Philosophy/Burke.htm.

“CBS Profile: Supreme Court Justices.” 2000. Available at http://cbsnews.com/now/story.

“Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer.” The Canadian & World Encyclopedia. Available at http://tceplus.com/ churchill.htm.

Davies, Stephen. “Margaret Thatcher and the Rebirth of Conservatism.” 1993. Available at http://www.ashbrook.org/publicat/onprin/v1n2/davies.html.

Dionne, E.J., Jr. Why Americans Hate Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991

Dole, Bob. Great Political Wit. New York: Doubleday, 1998

Encarta Encyclopedia. Available at http://encarta.msn.com.

Forse, Don T., Jr. “Media Bias?” 1997. Available at http://www.afatexas.org/document/news/other/mediabias.htm.

Gottfried, Paul. The Conservative Movement. New York:

Twayne Publishers, 1993.

“Initiatives for Access: Treasures – Magna Carta.” Available at http://www.bl.uk.diglib/magna–carta/overvoverview.html.

International Institute for Strategic Studies. “Country Profiles.” Economist Intelligence Unit of the U.S. Military, 2001.

“In Their Own Words: Journalists and Bias.” Available at http://www.aim.org/publications/special_reports/bias.html.

Johnson, Stephen D. and Joseph B. Tamney. “Social Traditionalism and Economic Conservatism: Two Conservative Political Ideologies in the United States.” Journal of Social Psychology, April 2001.

Johnston, Joseph F. “Conservative Populism— a Dead End.” National Review, October 19, 1984.

Keegan, John. “Sir Winston Churchill.” Available at http:// www.rjgeib.com/thoughts/britain/winston–churchill.html.

Kekes, John. A Case for Conservatism, Cornell UP: 1998.

Kirk, Russell. The Roots of American Order. Washington: Regnery Gateway, 1991.

Marlantes, Liz; Scherer, Ron; and Alexandra Marks. “To New Yorkers, He’s Churchill in a Baseball Cap.” Christian Science Monitor, September 12, 2001.

Olasky, Marvin. Compassionate Conservatism. New York: The

Free Press, 2000.

“Questions and Answers About the John Birch Society.” Available at http://www.jbs.org/about/weareask.htm

Ross, Kelley L. “Conservatism, History, and Progress.” 1996. Available at http://www.friesian.com/conserv.htm

Rossiter, Clinton. Seedtime of the Republic: the Origin of the American Tradition of Political Liberty.

Schrecker, Ellen. The Legacy of McCarthyism. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Marvin’s Press, 1994.

“The Rise and Fall of the Conservative Party.” Available at http://britishhistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa042001a.htm.

Further Readings

Busch, Andrew E. Ronald Reagan and the Politics of Freedom.

New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001. This book supports the premise of Ronald Reagan’s enduring legacy as a dominant force in American politics, and the effects his brand of conservatism has had upon contemporary politics.

Dillard, Angela D. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Now? New York: New York University Press, 2001. Author Dillard argues that political conservatism in the U.S. is no longer the domain of white, wealthy males, but instead involves persons of all races, ethnicities, gender, and sexualities.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

8 3 |

C o n s e r v a t i s m

Kelly, Charles M. Class War in America. Santa Barbara: Fithian Press, 2001. In this critical observation of conservative politics in action, author Kelly sub–titles his book: “How Economic and Political Conservatives are Exploiting Low– and Middle– Income Americans.”

http://www.heritage.org. The Heritage Foundation is a well–known conservative think tank in Washington, D.C., and actively promotes conservative views through its website and various publications.

National Review. In the ten years between 1955 and 1965, subscriptions to National Review increased from 30,000 to well over 100,000. This was primarily due to writer–editor William F. Buckley, Jr., whose opinions and editorials came to define American post–war conservatism.

SEE ALSO

Capitalism, Federalism, Liberalism, Republicanism

8 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

OVERVIEW

Fascism is a twentieth–century political ideology and movement based on nationalism and militarism, which emphasizes the importance of the state and the individual’s overriding duty to it. It opposes communism and liberalism, and seeks to regenerate the social, cultural, and economic life of its country by instilling its citizens with a powerful sense of national identity and an unquestioning loyalty to the state and its leader. Agencies of state control, such as secret police, and sophisticated propaganda techniques are important factors in the suppression of opposition and the advancement of fascist doctrines.

Drawing on nineteenth century theories, such as those of Friedrich Nietzsche and Georges Sorel, fascism arose out of the political and social destruction which followed World War I (1914–1918) and the Russian Revolution (1917), and reached its peak in the inter–war years between 1922–1939. Fascism was officially founded by Benito Mussolini, whose Fascist regime controlled Italy between 1922 and 1945, and derived its name from the fasces of ancient Rome, an axe tied up in a bundle of sticks which symbolized authority and justice. Italian Fascism proved to be the model for subsequent movements throughout Europe, most notably that of Germany. Under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, Nazism developed the nationalist principles of fascism into a blueprint for conquering Europe and establishing a racial hierarchy. The Third Reich’s attempts to create a “new order” led directly to the carnage of World War II, and to the German “mas-

Fascism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? Dictator

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Overthrow or

revolution

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Not interfere with

the state

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The state

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The state

MAJOR FIGURES Benito Mussolini; Adolf Hitler

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE Italy, 1922–1943

8 5

F a s c i s m

CHRONOLOGY

1918: First World War ends. Its aftermath creates the ideal conditions for Fascism’s development

1919: Benito Mussolini and the “Fascists of the First Hour” meet in Milan to form the Italian Fascist Party (PNF)

1921: Adolf Hitler becomes leader of the NSDAP (Nazi Party)

1922: Following the “March on Rome,” Mussolini is installed as Italian Prime Minister

1923–1924: Hitler is imprisoned for treason. While in Landsberg prison he writes Mein Kampf

1933: Hitler becomes German Chancellor. Almost immediately he passes the Enabling Act which awards him dictatorial powers

1936: Germany reoccupies the Rhineland and signs the Rome–Berlin Axis that unites Germany and Italy as allies. Outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in which Germany and Italy provide support for General Franco’s forces

1939: Italy invades Albania and signs the “Pact of Steel” with Hitler. Germany invades Poland provoking the outbreak of World War II

1941: Hitler and Mussolini declare war on the United States

1943: Allies invade Italy and Mussolini is removed from power

1945: Mussolini is shot dead by Italian partisans, Hitler and other Nazi party members commit suicide and Nazi Germany surrenders unconditionally to the Allies

ter race” inflicting terror and genocide on those who it deemed to be inferior.

Although the era of fascist domination ended in 1945, with the Allied victory over Italy and Germany, the influence of its ideology, as documented in Hitler’s Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”) and Mussolini’s Dottrina del Fascismo (“Doctrine of Fascism”), continues to exist on the political fringes of all Western democracies.

Within this common framework, however, there are certain characteristics which, although figuring prominently in some fascist movements, are absent in others. Arguably the most important of these differences lies in the militarist and nationalist doctrines of the various regimes, which range from an intense pride in national unity and traditions, through to a belief in racial superiority, ending ultimately in the overt racism, anti–Semitism and ethnic cleansing adopted by the Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler. These ideological inconsistencies have resulted in constant debate as to whether the authoritarian and nationalistic movements that arose in countries such as Spain, Romania, Austria, and France can be accurately described as fascist, or were merely foreign models of the original Fascist regime of Italy. If taken to its most basic and literal meaning, the term fascism applies only to the Italian regime which was founded and named by Mussolini although it is generally extended to encompass all comparable ideologies and movements. What is indisputable, however, is that to most people, fascism is primarily associated with the regimes of Benito Mussolini in Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany. Unfortunately, the well–documented manner in which its regimes mercilessly persecuted their national, political, and racial enemies has replaced much of fascism’s political meaning with more common use as a term of abuse and a generic symbol of evil and violence.

Despite this widespread demonization, and fascism’s inability to regain the political dominance it enjoyed from 1922 until the defeat of Germany and Italy in World War II in 1945, it would be foolish to dismiss its continuing influence and potential. The resurgence, especially in Eastern Europe, of authoritarian regimes with strong nationalist support, and the existence of fascist and neo–fascist movements on the political fringes of most Western democracies, only serves to highlight the need for continued study of fascism, in the hope of gaining greater understanding of its ideology, aims, and appeal.

HISTORY

Although fascism, as a political system, did not thrust itself upon the world until after World War I, the roots and influences of its political theory stretch back as far as the early nineteenth century. As a reaction to the values and ideals created during the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution that had swept across Europe during the eighteenth century, many intellectuals developed philosophies and con-

8 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

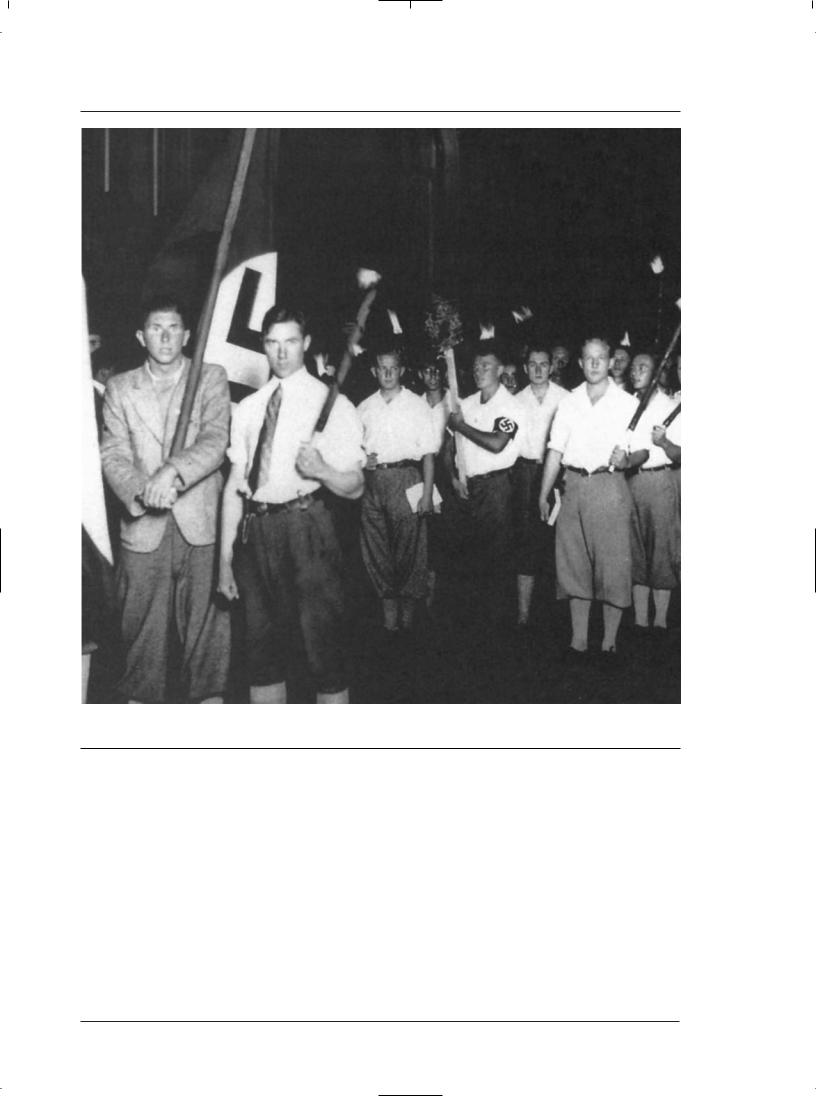

Nazi youth march in Berlin, 1933. (Archive Photos, Inc.)

cepts which would later be adapted to form the foundations of fascist ideology. Among those who opposed the new prevailing attitudes of rationalism, democracy, and liberalism, were the writers Johann von Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich von Schelling (1775–1854), who denied the claims that human nature could be explained in terms of general laws and dismissed the growing belief that politics and economics should aim for greater democracy and universalism. Along with other thinkers, known collectively as the Romantic Movement, Goethe and Schelling placed great emphasis on the importance of nationalism and tradition, and displayed a fervent hostility

towards society’s increasing adoption of material values.

The Romantic Movement’s philosophy was developed into a rejection of democracy as the ideal form of decision making by thinkers who adapted the works of Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), in particular his belief in the “general will.” Rousseau, a Swiss political philosopher, claimed that a natural, harmonious decision will emerge within a society on any issue, but this decision is not necessarily the one that would be chosen by a democratic majority. He added that, on certain occasions, the people may not be aware of this “general will” and it was the duty of those in

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

8 7 |

F a s c i s m

authority to invoke it. This theory has been linked to the fascist ideology of the strong, authoritarian state, making all decisions on behalf of its people and in the interests of the nation. In fairness to Rousseau, however, it is doubtful whether he intended for his theory to be interpreted in this way—his other assertions, in contrast to fascism, were that mankind was not inherently evil, and that ordinary people had the right and ability to bring about changes within their society.

During the course of the nineteenth century, the embryonic ideology of fascism gathered momentum and support in many European countries, with the continued rejection of liberal and democratic systems in favor of a return to traditional values and nationalism, under the guidance of a powerful, authoritarian state.

In France and Germany, nationalism progressed beyond its positive function of providing individuals with a shared heritage and a common identity and tradition. By coloring reason with emotion, and by selective interpretation of scientific and intellectual developments, the desire for national unity shifted sharply in the direction of racism. In France, Maurice Barres (1862–1923) introduced his theory of enracinement, which essentially suggested the existence of a mystical link between a country’s living and dead citizens, placing great emphasis on the importance of a nation to uphold the traditions and values of their ancestors. The views of Barres, along with those of his compatriots Comte Joseph de Gobineau (1816–1882) and Charles Maurras (1868–1952), founded the ideology on which Action Français (AF), considered by many historians to be the first fascist movement, was based. Formed in June 1899, AF united support from all sections of French society against the liberalism and universalism of the Republican government. With the influence of leading members, such as Georges Sorel (1847–1922) and Georges Valois (1894–1945), AF sought to reinstate the monarchy as the means of reuniting the nation and thereby placing France in a stronger position to defeat external and, more importantly, internal enemies. In France at this time, just as in other Western European countries, the major internal enemy was considered to be the Jews. Viewed as the materialistic and scheming epitome of capitalism, Jews became the convenient focus of the growing nationalist movement and proved an effective common enemy, upon whom society could blame their economic and political failures and disillusionment. However, neither AF nor any of its subsidiaries were able to turn this strong nationalist support into political success. What they had achieved was the setting in motion of a chain of ideas and events which, only a few years later, would see their ideology of extreme nationalism and strong control of the state become the

foundations of a new and powerful political system. Ironically, it would be not in France that fascism eventually obtained its political power, but in Italy and Germany (thus, the fascist regimes that French thinkers had so greatly influenced, almost succeeded in destroying France during World War II).

In Germany, as in France, the path of nationalism had moved from a healthy pride in their heritage and traditions to one of racism, anti–Semitism, and, ultimately, to fascism. The route of German fascism, however, would be influenced by thinkers who placed greater emphasis on the values of national and racial supremacy and military strength.

Before 1870, Germany was divided into many smaller states, the most important of which was Prussia. It was not until after the Prussian armies had defeated France at the Battle of Sedan in 1870 that the unification of Germany was realized, and Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) became the first Chancellor of the new Imperial German Federation. Yet, as far back as the sixteenth century, Germany possessed a strong sense of nationalism, evident in the popularity of the philosopher and religious reformer, Martin Luther (1483–1546). These values were later expanded upon by thinkers of the Romantic Movement, and by 1873, when German journalist Wilhelm Marr (1819–1904) published his highly successful book, The Victory of the Jew over the German, the seeds of anti–Semitism and the desire for racial purity were becoming generally promoted and accepted. The breakthrough, in terms of electoral support, came in 1887 when the independent, anti–Semitic candidate Otto Bockel was elected to the Reichstag (German parliament). Yet, his election was not as influential, in terms of fascist ideas, as the manner in which he carried out his campaign. In place of the normally low–key affair, Bockel organized mass rallies, consisting of marching bands and torchlight processions, all accompanied by the singing of nationalist songs and Lutheran hymns. This was a method that would be further developed and successfully employed by future fascist leaders.

Growth In the Twentieth Century

Germany The arrival of the twentieth century still found the growing number of nationalist and militarist movements relegated to the fringes of political power. Even the formation of the Pan–German League, with such popular commitments as emphasizing the will of the people and increasing German economic prosperity by expanding into Eastern Europe, led to minimal electoral support. After the elections in 1912, it was the socialists who had succeeded, for the first time, in becoming the German parliament’s largest party. The

8 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

F a s c i s m

majority of right wing groups, moderate and extreme, felt that radical measures were required to revive their popularity. Suggestions ranged from the establishment of a new, popular party to the setting up of an authoritarian regime; some activists even advocated the creation of a dictatorship. Two years later, with the onset of World War I, the nationalist and militarist movements seemed to have lost their momentum, as Germany united behind their government in expectation of a glorious victory, and the increased political and economic power that would inevitably follow in its wake. Indeed, had a swift victory occurred, then the course of world history may well have been very different. This was not the case, however, and as the war continued the German people faced increasing hardship, which in turn led to signs of unrest and dissent. The nationalist movements seized on this as their opportunity, and in September 1917 witnessed the formation of the German Fatherland Party (GFP), the first mass party within Germany to be founded on the developing fascist ideology. By proposing the annexation of states along Germany’s eastern borders, and by deflecting criticism from the government and military by blaming the ailing war effort on the Jewish population, the GFP had, by July 1918, amassed a membership of 1.25 million.

By October 1918, the leaders of the German military were aware that defeat was inevitable and, in order to shirk from the responsibility of their failure, plans were drawn up which transferred the reins of power from the Imperial hierarchy to a new, democratic government. On November 9, 1918, one day after Kaiser Wilhelm I (1859–1941) had been secretly escorted to Holland, Germany was officially declared a republic. The first duty of the new leadership was to unconditionally surrender to the victorious Allies and, two days after succeeding to power, Matthias Erzberger (1875–1921) signed a formal armistice on behalf of the new government. The humiliation felt by the German people and military was intensified by the conditions imposed on their country by the Allies in the Treaty of Versailles. Among the requirements was that Germany must accept full responsibility for starting the war, and that the regions of Alsace and Lorraine should be returned to France. It also ordered major demilitarization and limitations of the German armed forces, changes to Germany’s eastern boundaries, the removal of all German colonies, and a commitment to the paying of restorative compensation to the Allies. The war had shattered German society and they now required someone on whom to place blame, both for the defeat and for the humiliating aftermath. The Germans found two convenient scapegoats in their newly formed democratic government and the

Jews. What the German people now sought was the rebirth of their country and the restoration of their national identity and pride, but they no longer believed that the politics of liberalism and democracy would provide this. The German state was collapsing and the people demanded radical changes.

Italy Ironically, one of Germany’s enemies in the war, Italy, experienced a similar feeling of national despair and frustration. Although Italy had emerged on the winning side, the cost of their victory had been a national, social, and economic crisis that resulted, just as in Germany, in the desire for a strong, nationalist political party to lead them out of the post–war chaos and confusion. The combination of intense public disillusionment and the general collapse of the old political order contributed to a rapid growth in the popularity of the developing Fascist movement and its leaders. The head of one such movement was quick to observe that a political void now existed, and within one year of the war’s conclusion, Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) had added the term Fascism to the political dictionary, and laid the foundations of the first Fascist political party.

Just as in Germany, the political, economical, and social effects of World War I proved to be the most significant factors in the development and popularity of Italian fascism. However, the political ideology of the National Fascist Party, and the reasons for its subsequent rise to power, had roots which lay far deeper in Italy’s history.

Corresponding very closely to the development of Germany, Italy as a unified nation did not exist until 1870. Prior to this it had consisted of an assortment of independent city–states, interspersed with several kingdoms under the control of autocratic foreign dynasties. The first half of the nineteenth century had spawned a national independence movement, known as the Risorgimento, which sought to establish a united and independent Italian state. The major figures of this nationalist movement were Camillo Cavour (1810– 1861), Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) and Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872). Garibaldi and his Redshirts, a renowned army of one thousand red–shirted volunteers, conquered the major kingdom of Naples in 1861 and throughout the 1860s Italy gradually moved closer to unification. The process was completed, under the guidance of Cavour, in 1870. Unfortunately, although Italy was now officially united, in terms of politics, economics, and geography a great deal of division remained. Italy was, in effect, a dual economy, with the more advanced, industrialized areas being concentrated in the north, while the rural economy of the south was beset with problems of illiteracy and

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

8 9 |

F a s c i s m

underemployment. Politically, Italy was governed by a succession of elitist coalitions, which were unstable and short–lived, causing the people to feel increasingly alienated and resulting in major public unrest. The instability of the new political system was intensified when the Vatican, who objected to losing the Papal States during the unification process, refused to cooperate with the new state, and announced a papal ban which prohibited any participation in politics.

Italy’s defeat by the Ethiopians at the Battle of Adowa in 1896 further exposed the weakness of the Italian state, and proved yet another blow in their quest for national glory and stability. The Italian people’s discontentment with their leadership became increasingly apparent and, in the years immediately preceding World War I, there was a rapid development in the popularity of both socialism and a new, organized nationalist movement.

While the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) was establishing itself as the largest political party within the coalition government, a small group of intellectuals and writers were laying the foundations of the Italian Nationalist Association (ANI). Officially formed in Florence in 1910, and containing key figures such as Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938), Enrico Corradini (1865–1931) and Giovanni Papini (1881–1956), the ANI adopted a doctrine which focused on the creation of a strong, authoritarian state and a commitment to providing rapid economic growth. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the ANI and their nationalist beliefs were gaining support from all sections of society, including many disillusioned socialists. One of these was Benito Mussolini, whose conversion to nationalism and decision to support, rather than oppose, the war resulted in him being dismissed as editor of the socialist party newspaper, Avanti!. Upon returning wounded from the war, Mussolini set up his own newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia (The People of Italy), in which he criticized the government and opposition political parties, while promoting his own nationalist and militarist views.

Birth of Fascism

The official birth of fascism is generally accepted as occurring on March 23, 1919, when Mussolini met with the “Fascists of the First Hour” at the Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan. This gathering, which brought together elements from the extreme right and left of Italian politics, including groups such as the Italian National Association and the Futurists, led directly to the formation of the Fasci di Combattimento, the first self–styled Fascist movement. As its symbol, the group adopted the fasces, an ancient Roman emblem of authority and punishment, consisting of a bundle of

rods bound together with a protruding axe head. Although the membership of the Fasci di Combattimento was drawn from all points of the social and political spectrum, most had served in the war, which was of crucial importance to Mussolini, who firmly believed that only a “trenchocratic” regime would be capable of creating a regenerated Italy. He was also of the opinion that the use of violence was necessary to achieve major political goals, whether directly or as a means to suppress the opposition. The Fasci di Combattimento was controlled by an elected central committee, the order of the hierarchy being determined by the number of votes gained by each successful candidate. Mussolini secured the number one position. This, however, was his only successful election in 1919, as in the November national elections the newly formed fascist movement attracted minimal support. Mussolini and the Fascist Central Committee, attributed their failure to the electorate’s distrust of policies which advocated extreme left– and right–wing measures. In order to redress this imbalance, the Fascist movement distanced themselves from many of their left–wing programs and embarked on a definite shift towards the right.

This further drift towards extremism manifested itself most visibly in the increased level of violence, and in the para–militarism of these attacks. Originally employed on a small scale, in order to intimidate opposition groups and defend those attending Fascist meetings, these tactics soon changed with the setting up of the squadristi. These were fascist squads, composed mainly of disillusioned ex–servicemen, who increasingly took on a paramilitary role and favored the use of more threatening tactics. To visually reinforce their militarism, the squadristi adopted the black– shirted uniform and the one–armed salute employed during the war by the arditi, who were the elite troops of the Italian army. Although Mussolini exercised overall command, at a local level each of these squads was under the control of Fascist leaders known as ras, the name being taken from the Ethiopian word for chieftain. By early 1921, Mussolini had growing concerns about the ruthless tactics being employed by the squadristi, and the power and influence that certain of the ras had achieved. Although he was in favor of using violence to achieve specific goals, Mussolini was, at that time, attempting to portray Fascism as a stable and credible political force, and was concerned that the excessive brutality of many squads would undermine his plans. His solution was to formalize the status of the Fascis di Combattimento as an official political party.

When the Fascis di Combattimento was first formed, Mussolini deliberately avoided setting it up

9 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |