- •Subject

- •Subject Complement

- •Noun Phrase Modifier

- •Determinatives

- •Appositive

- •Adverbial

- •Common and Proper Noun

- •Defining a Common Noun

- •Defining a Proper Noun

- •Common and Proper Noun

- •Tips for Understanding the Proper Noun

- •Practice with Common and Proper Nouns

- •Direct Object

- •Prepositional Complement

- •Possessive Determiner

- •Adverbial

- •List of auxiliary verbs

- •Linking Verbs

- •Words That Are True Linking Verbs

- •Forms of "to be"

- •Individual work Seminar 3

Possessive Determiner

Relative pronouns fourthly function as the possessive determiner in adjective clauses. A possessive determiner is a word that indicates possession of or some other relationship to a noun phrase. Take for example the following two sentences:

The neighbor is a very nice old man.

My brother installed his fence.

As with other adjective clauses, these two sentences can combine into a single sentence with the help of a relative pronoun. First, the relative pronoun whose replaces the possessive determiner his in the second sentence to form the clause my brother installed whose fence. Then, the direct object whose fence is fronted to the beginning of the clause to form the adjective clause whose fence my brother installed. Finally, the adjective clause attaches to the noun neighborin the first sentence to form the sentence The neighbor whose fence my brother installed is a very nice old man. The relative pronoun whose functions as the possessive determiner in place of his.

The relative pronoun that can function as the possessive determiner in an adjective clause is whose. Other examples of relative pronouns functioning as possessive determiners include:

The man whose dog she walks is her neighbor.

I really enjoy the author whose books were just published.

Mary is the woman whose children play with mine.

Adverbial

Relative pronouns fifthly function as the adverbial in adjective clauses. An adverbial is a word, phrase, or clause that modifies an entire clause by providing additional information about condition, concession, manner, reason, result, place, or time. Take for example the following two sentences:

The candles are at the store.

The store also sells party supplies.

These two sentences can similarly combine into a single sentence with the help of a relative pronoun. First, the relative pronoun where replaces the adverbial at the store in the first sentence to form the clause the candles are where. Then, the adverbial where is fronted to the beginning of the clause to form the adjective clause where the candles are. Finally, the adjective clause attaches to the noun store in the second sentence to form the sentence The store where the candles are also sells party supplies. The relative pronoun where still refers to the adverbial at the store making where the adverbial in the adjective clause.

The three relative pronouns that can function as the direct object of an adjective clause are when, where, and why. Other examples of relative pronouns functioning as adverbials include:

The reason why you handed in your homework late sounds like a lie.

Do you remember the time when we ate an entire pie in one sitting?

The hotel where we stayed on vacation had lovely rooms.

Relative pronouns that function as adverbials are also referred to as relative adverbs.

Grammatical categories of the pronouns

Gender masculine, feminine, neuter (personal, possessive)

Case: nominative, objective (personal, interrogative and relative WHO ), common, genitive (indefinite, reciprocal, negative)

Number sg., pl. (demonstrative and the defining OTHER)

Grammatical Categories

- Case, gender, number, person

(1) case

- N: common case x morphologically marked possessive case

- PRO: marked subject case x object case x possessive case (possessive PRO)

- X you and it not marked for case

- Formal: PRO following the verb be, i.e. not followed by the finite V form> subject case

- X colloquial: ...> object case: it's all right, it's only me

(2) gender

- Manifested in 3rd person SG personal / reflexive / possessive PRO

- Relative / interrogative PRO: personal (who) x non-personal gender (which)

(3) number

- Manifested in special lexical entry: I> we; he / she / it> they

- X exceptional regular PL formation by the - (e) s ending: yourself> yourselves; other> others; one> ones

- Demonstrative PRO: SG this> PL these; SG that> PL those

(4) person

- Manifested in personal / reflexive / possessive PRO

- 1st person = the speaker

- 2nd person = the addressee

- 3rd person = "the rest"

- Colloquial: you / they = also with the meaning of a general human agent (you change three times / where do they sell it?)

- Formal: we / one = ... (one does not like to have one's word doubted)

The article as a specific determiner of the noun.

The linguistic status of the article

The question is whether the article is a separate part of speech (i.e. a word) or a word-morpheme. If we treat the article as a word, we shall have to admit that English has only two articles - the and a/an. But if we treat the article as a word- morpheme, we shall have three articles - the, a/an, ш.

B.Ilyish (1971:57) thinks that the choice between the two alternatives remains a matter of opinion. The scholar gives a slight preference to the view that the article is a word, but argues that “we cannot for the time being at least prove that it is the only correct view of the English article”. M.Blokh (op. cit., 85) regards the article as a special type of grammatical auxiliary. Linguists are only agreed on the function of the article: the article is a determiner, or a restricter. The linguistic status of the article reminds us of the status of shall/will in I shall/will go. Both of the structures are still felt to be semantically related to their ‘parent’ structures: the numeral one and the demonstrative that (O.E. se) and the modals shall and will, respectively.

The articles, according to some linguists, do not form a grammatical category. The articles, they argue, do not belong to the same lexeme, and they do not have meaning common to them: a/an has the meaning of oneness, not found in the, which has a demonstrative meaning.

If we treat the article as a morpheme, then we shall have to set up a grammatical category in the noun, the category of determination. This category will have to have all the characteristic features of a grammatical category: common meaning + distinctive meaning. So what is common to a room and the room? Both nouns are restricted in meaning, i.e. they refer to an individual member of the class ‘room’. What makes them distinct is that a room has the feature [-Definite], while the room has the feature [+Definite]. In this opposition the definite article is the strong member and the indefinite article is the weak member.

The same analysis can be extended to abstract and concrete countable nouns, e.g. courage: a courage vs. the courage.

Consider: He has a courage equaled by few of his contemporaries. vs. She would never have the courage to defy him.

In contrast to countables, restricted uncountables are used with two indefinite articles: a/an and zero. The role of the indefinite article is to individuate a subamount of the entity which is presented here as an aspect (type, sort) of the entity.

Consider also: Jim has a good knowledge of Greek, where a denotes a subamount of knowledge, Jim’s knowledge of Greek.

A certain difficulty arises when we analyze such sentences as The horse is an animal and I see a horse. Do these nouns also form the opposemes of the category of determination? We think that they do not: the horse is a subclass of the animal class; a horse is also restricted - it denotes an individual member of the horse subclass. Cf. The horse is an animal. vs. A horse is an animal.

Unlike the nouns in the above examples, the nouns here exhibit determination at the same level: both the horse and a horse express a subclass of the animal class.

The adjective and its categorial meaning.

The adjective is a part of speech which denotes the property of substance. This is the nominative class of words though functionally limited as compared with nouns. This means that adjectives are not supposed to name objects: they can only describe them in terms of the material they are made of, their colour, size, quality, etc: red, white, big, high, long, good, kind, happy. Therefore they find themselves semantically and syntactically bound with nouns or pronouns: We bought white paint. We painted the door white. She is a happy woman. She is happy. He made her happy.

The exceptions are substantivized adjectives, i.e. those that in the course of time have been converted to nouns and therefore have acquired the ability to name substances or objects: The bride was dressed in white. You mix blue and yellow to make green.

Categorial meaning – property of a substance (qualitative / relative)

Grammatical category of the adjective

The English adjective has lost in the course of history all its forms of grammatical agreement with the noun. As a result, the only paradigmatic forms of the adjective are those of degrees of comparison.

The meaning of the category of comparison is expression of different degrees of intensity of some property revealed by comparing referents similar in certain aspects. The category is constituted by the opposition of the three forms: the basic form (positive degree) that has no features of comparison, thecomparative degree form and thesuperlative degree form. The comparative degree shows that one of the subjects of comparison demonstrates quality of higher intensity than the other; the grammatical content of the superlative degree is intensity of a property surpassing all other objects mentioned or implied by the context or situation. However, some adjectives are not capable of forming the degrees of comparison. As a rule, these “deficient” words belong to the class of relativeadjectives though, when used metaphorically, even they may occur in the form of the degrees of comparison.

Qualitative adjectives generally have the degrees of comparison. However, distinction should be made between qualitative adjectives which have “gradable” meanings and those which have “absolute” meanings. For example, a person may be more or less strong, and strong is a gradable adjective for which corresponding gradations are expressed by means of the forms stronger – the strongest. Contrasted to adjectives with such “gradable” meanings are qualitative adjectives denoting some absolute quality (e.g.real, equal, right, blind, dead, etc.). These are incapable of such gradations.

Another group of “non-comparables” is formed by adjectives of indefinitely moderated quality, such asyellowish, half-sarcastic, semi-conscious, etc. But the most peculiar word group of non comparables made up by adjectives expressing the highest degree of а quality. The inherent superlative semantics of these “extreme adjectives” is emphasized by the definite article normally introducing their nounal combinations,the ultimate result, the final decision. On the other hand, in colloquial speech these extreme qualifiers can sometimes be modified by intensifying elements. Thus, “the final decision” may be changed into “a very final decision”; “the crucial factor” is transformed into “quite a crucial factor”, etc.

The morphological form of the degrees of comparison is restricted by the phonetic structure of a word, namely its syllabic structure: linguists have no doubts about the degrees of comparison of monosyllabic words forming their paradigm by means of the inflections -er and -est: long – longer – the longest.

Adjectives of two syllables may change either morphologically or with the help of the quantifiers lovely –lovelier (more lovely) the loveliest (the most lovely). There are also other limitations. For example adjectives ending in two plosive consonants (e.g. direct, rapt) do not have morphological forms. Nevertheless, the adjective strict with its forms stricter – the strictest is the example of the opposite. Polysyllabic adjectives do not have morphological forms of the degree of comparison. The intensity of a property is expressed here with the help of the quantifiers: interesting – more interesting — the most interesting.

Grammarians seem to be divided in their opinion as to the linguistic nature of degrees of comparison formed by means of more and (the) most. There is quite a widespread point of view that these word combinations are analytical forms of adjectives, since they are seemingly parallel to the morphological forms. However, there are arguments that may undermine this claim. Firstly, analytical forms do not presuppose the possibility of repetition of auxiliaries, which is quite typical of more: Her e-mails become more and more emotional. Secondly, the adverbs more and most, as a rule, preserve their lexical meaning and – which is important – they are lexically opposed to word combinations with less and least, denoting respectively the decrease of intensity. It would be therefore quite consistent to classify the latter word combinations as analytical forms as well but in this case the parallelism with the morphological system proper is broken. On the other hand, phrases with more and most include also so-called elative word combinations (e.g. It was a most spectacular panorama) that are used to convey a very high degree of some property without comparing it to anything. It is important to note that the definite article with theelative construction is also possible. In this case the elative function is less distinctly recognizable, e.g. Ifound myself in the most awkward situation. Interestingly, though the synthetic superlative degree can be used in the elative function as well (e.g. It is the greatest pleasure to talk to you), grammarians notice the general tendency to use the superlative elative meaning in the most-construction.

If these elative forms are seen as analytical ones, then, taking into account their semantic similarity, word combinations with very, extremely, totally, awfully should also be considered in the same way. In this case it is obvious that the term “analytical form” becomes vague and amorphous. Also, more and most may easily combine with nouns, e.g. more taste, more money, most nations, etc. However the main argument against the notion of analytical forms of comparison lies in syntactic meaningfulness of the adverbs moreand most. There is no syntactic relation between the components of analytical forms, whereas more andmost preserve the adverbial relation with adjectives to the same extent as any other adverbs of degree: cf.less generous, very generous, rather generous, extremely generous, more generous.

If the more/most-constructions are treated as analytical forms, the constructions with less and least, as soon as they convey the opposite meaning, can only belong to units of the same general order, i.e. to the category of comparison. According to this interpretation, the less-least combinations constitute specific forms of comparison, which are called by the supporters of this viewpoint “forms of reverse comparison”. As a result, the whole category includes not three, but five different forms, making up the two series – direct and reverse. The reverse series of comparison (the reverse superiority degrees) is of far lesser importance than the direct one. This phenomenon can be explained by semantic reasons, as it is more natural to follow the direct model of comparison based on the principle of addition of qualitative quantities than on the reverse model of comparison based on the principle of subtraction of qualitative quantities, since subtraction in general is a far more abstract process of mental activity than addition. It can also be conjectured that, for this very reason, the reverse comparatives and superlatives are rivaled in speech by the corresponding negative syntactic constructions (e.g. The news is not so shocking as the one I expected).

Word-building affixes: -ful, -less, -ish, - ous, -ive, -te, -ic, in-, ir-, im-.

Grammatical category of degrees of comparison (gradual ternary opposition)

Elative superlative

The elative superlative

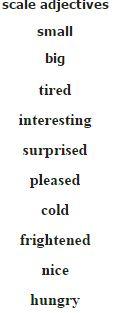

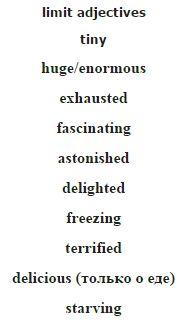

limit and scale adjectives

‘Limit’ and ‘scale’ adjectives

‘Very marvellous' is not really good!

Этот урок является дополнением к предыдущему, поэтому разговор пойдет опять о прилагательных. Явление, которое мы сегодня рассмотрим, существует как в английском так и в русском языках, но используется неосознанно, то есть никто о нем, как правило, не задумывается.

Есть такая категория прилагательных, которые выражают признаки, но насколько сильно этот признак выражен показывают дополнительные слова.

Например: «хороший». Понятно, что смысл позитивный, но насколько хороший: довольно хороший или очень хороший? А может не очень хороший? Чтобы передать оттенки значения, нужно использовать дополнительные слова: «довольно», «очень», «не очень».

Такие же прилагательные существуют и в английском языке и называются они: “scale adjectives”: good, bad, small, big, etc.

Прилагательные другой категории выражают признак в крайней его степени. Например: «отвратительный» - уже выражает крайне негативную оценку. Мы не говорим: «очень отвратительный». Хотя выражение «совершенно отвратительный» существует и используется для придания речи выразительности. В английском такая группа прилагательных называется “limit adjectives”.

Приводим небольшую таблицу противопоставления scale adjectives и limit adjectives.

Кстати, предложение: I'm absolutely starving. можно перевести как Я умираю с голоду./Я очень хочу есть.

Правило употребления scale adjectives и limit adjectives – чрезвычайно простое:

-

слово very не

употребляется с limit adjectives. Таким образом,

нельзя сказать Very marvellous.

-

слово absolutely не

употребляется с scale adjectives: absolutely

good.

- слово really употребляется с обоими: really marvellous, really good.

«Ну вот!» - скажете Вы – «Раньше мы из-за таких мелочей вообще не заморачивались! А теперь надо над каждым словом задумываться.»

Заморачиваться или нет – решайте сами, но мы считаем: предупрежден – значит вооружен.

ubstantivation of adjectives

The substantivation of adjectives may be either complete or incomplete. In the case of complete substantivation, words like a native, a relative, a conservative, an alternative, a cooperative, a derivative, a savage, a stupid, a criminal, a black, a white, a liberal, a radical, a general, a corporal, a Russian, an American, a Greek, a Hungarian, a weekly, a monthly and so on share all the nounal grammatical characteristics: number, case, the ability to be used with the definite and indefinite articles: a native, two natives, the native's hut; an American, two Americans, the American's accent.

The incomplete substantivation presupposes only some of nounal grammatical characteristics. For example, some of substantivized adjectives have only the plural form: valuables, eatables, ancients, sweets. Most of substantivized adjectives of the kind are similar to collective nouns since they denote a whole class. They are used with the definite article: the rich, the poor, the unemployed, the black, the white, the deaf and dumb, the English, the French, the Chinese. In a sentence they are normally associated with a plural verb: The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

The substantivized adjectives denoting abstract notions are used with the definite article but are associated with the singular verb: the good, the evil, the beautiful, the future, the present, the past: The evil that men do lives after them/The good is oft interred with their bones. (W. Shakespeare)

The numeral as a part of speech.

While the noun, the adjective, and the verb are characterized by all the three properties of a part of speech – morphological, syntactic and semantic, the numeral, like the pronoun, is distinguished only due to its lexical meaning. Numerals indicate exact number or the order of persons and things in a series.

Accordingly,numerals ae divided into cardinal numerals(cardinals) and ordinal numerals(ordinals).

Numerals have no morphological paradigm, which distinguishes them from the nouns dozen, score, half, etc. that have a similar lexical meaning but combine it with the category of number. The same holds for the cardinals hundred, thousand, million that are numerals when they indicate exact number: two thousand five hundred and twelve. The nouns used to denote a vast amount approximately, without indicating an exact figure and functioning in the plural form, are their homonyms: e.g. thousands of cars, by twos and threes. The lack of a paradigm makes numerals different from the adjectives many, much, few and little that have the forms of comparison.

Another morphological property of numerals is their system of word-building suffixes. The cardinal numerals from 13 to 19 are derivatives with the suffix -teen; the cardinals indicating tens are formed by means of the suffix -ty; the cardinal numerals from 21 to 29, from 31 to 39 are compound, whereas ordinalsare formed by means of the suffix -th, with the exception of the first three suppletive forms -first, second, third.

Syntactically numerals are less distinct from other parts of speech. Thus, they may carry out functions common for nouns and adjectives:

Two [attribute] big ideas, not just one, arc at issue: the evolution of all species, as a historical phenomenon, and natural selection, as the main mechanism causing that phenomenon. The first[subject] is a question of what happened. The second [subject] is a question of how. (Quammen)

“In our lifetime, ” says economist Robert K.Kaufman of Boston University, who is forty-six [predicative],“we will have to deal with a peak in the supply of cheap oil. ” (Appenzeller)

Last year newly prosperous professionals snapped up over two million [object] – up 70 percent of cars over 2002. (Appenzeller)

Using data from the US Geological Survery, Greene presents a brighter picture, with world production most likely to peak around 2040 [adverbial modifier of time]. (Appenzeller)

It should be mentioned that, in the sentence, both cardinal and ordinal numerals perform, as a rule, the attributive function. It should be noted, however, that the substantivized position is most frequently caused by anaphoric use:

It could be five years from now or thirty: No one knows for sure, and geologists and economists are embroiled in debate about just when the “oil peak” will be upon us. (Appenzeller)

Cardinal numerals, i.e. those indicating exact number, are used non-anaphorically if they denote an abstract number: Two and two is four. In the attributive position cardinal numeral influences the form of a noun – singular or plural: one day – two days.

Ordinal numerals, indicating a fraction denominator, are completely substantivized and are used in the plural form:

In the US about two-thirds of the oil goes to make fuel for cars, trucks, and planes. (Appenzeller)

Cardinal numerals may also be used with the definite article: No one moved: the two were waiting for the right moment to strike. These cases may be interpreted as partially substantivized.

Absence of formal, i.e. morphological properties, as well as lack of specific, peculiar to numerals only syntactic functions was the reason for dismissing numerals as part of speech. The dismissal resulted in that numerals were treated as subgroups of nouns or adjectives, which is quite typical of Western linguists. Sometimes only cardinal numerals are treated as numerals proper, while ordinal numerals are referred to adjectives, since they have no specific properties. It may be argued, however, that in this case researchers completely neglect close ties between cardinals and ordinals, revealed both in their lexical meaning and in their derivation patterns. All in all, one can’t but notice that, thought the two types of numerals – cardinals as well as ordinals – may coincide syntactically with nouns and adjectives, still they share a specific lexical meaning.

The verb as a part of speech, its categorial meaning.

The verb is the most complex part of speech. This is due to the central role it performs in realizing predication - connection between the situation given in the utterance and reality. That is why the verb is of primary informative significance in the utterance. Besides, the verb possesses a lot of grammatical categories.

Furthermore, within the class of verbs various subclass divisions based on different principles of classification can be found.

Semantic features of the verb. The verb possesses the grammatical meaning of verbiality - the ability to denote a process developing in time. This meaning is inherent not only in the verbs denoting processes, but also in those denoting states, forms of existence, evaluations, etc.

Morphological features of the verb. The verb possesses the following grammatical categories: tense, aspect, voice, mood, person, number, finitude and temporal correlation. The common categories for finite and non-finite forms are voice, aspect, temporal correlation and finitude. The grammatical categories of the English verb find their expression in both synthetical and analytical forms.

Syntactic features. The most universal syntactic feature of verbs is their ability to be modified by adverbs. The second important syntactic criterion is the ability of the verb to perform the syntactic function of the predicate. However, this criterion is not absolute because only finite forms can perform this function while non-finite forms can be used in any function but predicate.

English verbs have general categorial meaning that is of process presented as being developed in time and being embedded in the semantics of all verbsincluding those that denotestate(seem, sleep, contain, matter, mean), forms of existence (live, keep, remain, stay, wait), mental activities (think, believe, guess, suppose, recognize), emotional attitudes (love, hate, adore, respect, despise, fear).The common verb-forming derivational means are as: affixation - prefixes: re-, dis-, over-, de-, mis-, under-, un-, en-, in-: e.g. reorganize, rebuild, dislike, disconnect, overhear, overcome defrost, devalue, misunderstand, mispronounce, undercook, undergo, unload, unpack, enclose, enforce, insure, inquire; suffixes: -ize, -en, -ate, -ify, -ish: e.g. characterize, computerize, flatten, broaden, differentiate, operate, clarify, intensify, furnish, finish; conversion -as a zero-derivation when a noun acquires the verbal features: e.g. to pencil, to watch, to wallpaper, to effect, to float, to flood, to humour; compounding: e.g. blackmail, brainstorm, babysit, ice-skate, intercross, key wind, kidnap, manhunt.

The division of the verbs into stativeand dynamicmakes up the distinguishing feature of the grammar. The first are those denoting processes without any qualitative change, the duration of which is unlimited (e.g. know, remember, own, want, hate, like, prefer). The second denote processes that have a marked qualitative change the duration of which is limited (e.g. arrive, come, change, build).

The verbal core as a lexeme normally forms the part of a grammatical verb form together with ending morphemes and auxiliaries. A lexeme plus a grammatical affix alone or with a suppletive change is called a single grammatical form(e.g. writes/wrote, go/went, walks/walked, enter/entered); a grammatical form which consists of more than one word, with an auxiliary, makes a combined grammatical form,being more typical of analytical English (e.g. is painted, have been swimming, will have been reading).

As to the verbs functional significance (syntactical functions and their association with the subject and the object), the main classes of verbs are clearly cut: notional,structuralandmodal verbs.Structuralsare subdividedinto auxiliary and linking verbs or copulars. Notionalverbs have a full lexical meaning of their own and can be used in a sentence as a simple predicate: e.g. He lived/ They are writing/ We shall read/ She has told. Notional verbs cover the following semantic areas:activity verbs: bring, buy, carry, work, throw, run, move, jump, plant;communication verbs: admit, answer, argue, discuss, explain, announce, speak, reply, whisper, propose;mental verbs: consider, think, decide, learn, research, believe, speculate, explore, prove;physical state: rain, snow, freeze, sleet;perception verbs: see, notice, hear, smell, taste, feel;verbs of single occurrence: happen, fall, disappear, change, occur, put, show, find;causative verbs: encourage, urge, make, let, persuade, require, help, prevent, enable;emotive verbs: admire respect, suspect, threat, dislike, fear, contempt.

Auxiliary verbs are those which have no lexical meaning of their own and are used as function wordswith a function to make up analytical grammatical forms. In English auxiliary verbs (e.g. be, do, did, will, shall, have, should, etc.) are used in corresponding grammatical forms to express tense, mood, aspect, voice, negative/interrogative. The three verbs ‘be, have, do’ can be observed as notional verbs in the meaning of ‘existence, possession, physical activity’ and auxiliaries. Close to the auxiliary by their function are modalverbs: e.g. can, may, must, have to, need, should, shall, ought to. They cannot be used independently unaccompanied by notional verbs; the meaning of process is very scarce and is dominated by the meaning of modality: ability, possibility, probability, permission, necessity, obligation, prohibition, logical assumption, etc. The combinality of an English modal verb is specified by the forms of an infinitive (simple, continuous, perfect): e.g. could have spoken, must be visiting, should have been studying. Apart from auxiliaries and modals, notional verbs are opposed to linkingverbs, which have partly lost their lexical meaning and are used as part of a compound nominal predicate: current copular verbs: be, seem, keep, remain, stay, feel, look, taste, smell; resulting copular verbs: become, turn, get, prove, appear, come, turn out.

Mainly, the basic feature of the verb lies in their division into transitiveand intransitiveverbs, according to their association with the subject and the object of the process, i.e. according to the verbal valency of being combined with the subject (personal or impersonal) and the object (direct, indirect and prepositional). Transitiveare the verbs characterized by the fact that they relate a preceding subject to the following object: e.g. He is reading sth/ He has written sth/ He will meet sbd). They are of two types:monotransative, when they occur in a verb phrase with a single direct object: e.g. put, spend, wear, find, produce, hold, carry, use);ditransative, when they occur with two objects (direct and indirect): e.g. give sth to sbd, buy sth for sbd, send sth to sbd, write sth to sbd.Intransitiveverbs are characterized by the fact that they never occur with the object: e.g. disappear, rain, work, happen, arrive, sleep, exist, stand. There are the verbs of dual nature, being both transitive and intransitive: e.g. win, win a game; eat, eat dinner; try, try sth; remember, remember the event; read, read a book; study, study the subject.

As regards formal features, distinctive is the existence of the two groups of English verbs in accordance to the ways of forming the Past Simple and Past Participle (regular and irregular); above all, English is made to stand out due to the group of multi-word verbs, which consist of phrasalverbs (e.g. take in, hold on, make out, fill in, keep up, bring out, come down, fall for), prepositionalverbs (e.g. ask for, insist on, say to, wait for, deal with, smile at, apply to, result in) and phrasal prepositionalverbs (e.g.put up with, look forward to, turn back to, get on with, catch up with, come up with hand over to).

The grammatical features of the verb are outlined like the following: categorical meaning of process being developed in time and embedded in semantics of a verb with or without a qualitative change; structural dimensions of a verb reflected in its subcategorisation; verb-forming derivational patterns alongside its peculiarities in grammatical forms; categorical changeable forms of tense, aspect, taxis, voice, mood, person, number; opposition of finite vs non-finite verb-forms: the finite as performing the function of a finite predicate(We have run out of bread) and the non-finite as performing non-verbal functions: subject (Eating vegetables is healthy), attributive (This is the best way to relax), adverbial (While walking, take care of yourself), object (They avoided arguing); functional significance expressed in certain syntactic functions in association with types of combinality

Categorial meaning – dynamic process, process developing in time

Syntactic function – predicate

Formal characteristics of verbs

1. According to their stem-types all verbs fall into: simple (to play), sound-replacive (food - to feed, blood - to bleed), stress-replacive (‘insult - to in’sult,‘record - to re’cord), expanded - built with the help of suffixes and prefixes (oversleep, undergo), composite - correspond to composite nouns (to blackmail), phrasal (to have a smoke, to take a look).

2. According to the way of forming past tenses and Participle II verbs can be regular and irregular.

Lexical-morphological classification is based on the implicit grammatical meanings of the verb.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of transitivity/intransitivity verbs fall into transitive and intransitive.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of stativeness/non- stativeness verbs fall into stative and dynamic. Dynamic verbs include:

1) activity verbs: beg, call, drink;

2) process verbs: grow, widen, narrow;

3) verbs of bodily sensations: hurt, itch;

4) transitional event verbs: die, fall;

5) momentary: hit, kick, nod.

Stative verbs include:

1) verbs of inert perception and cognition: adore, hate, love;

2) relational verbs: consist, cost, have, owe.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of terminativeness/non- terminativeness verbs fall into terminative and durative. This classification is closely connected with the categories of aspect and temporal correlation.

Syntactic function of the verb

According to the nature of predication (primary and secondary) all verbs fall into finite and non-finite.

Functional classification

According to their functional significance verbs can be notional (with the full lexical meaning), semi-notional (modal verbs, link-verbs), auxiliaries.

Auxiliaries are used in the strict order: modal, perfective, progressive, passive.

Semantic classification of verbs

Notional verbs: actional and statal; limitive and unlimitive.

|

|

Verb is a part of speech with grammatical meaning of process, action. Verb performs the central role of the predicative function of the sentence. Verb is a very complex part of speech and first of all because of it’s various subclass division. If we admit the existence of the category of finitude as Prof.Blokh does that we’re divide all the verbs into 2 large sets: the finite set and non-finite set. They are profoundly different from each other. Here we will talk about the finite verbs. As we have said the general processual meaning is in the semantics of all the verbs including those denoting states, forms of existence and combinability. It mainly combines with nouns and with adverbs. Syntactical function is that of the predicate, because the finite verb expresses the processual categorial features of predication that is time, voice, aspect and mood. Verbs are characterized by specific forms of word-building. The stems may be simple ex: go, take, read. Sound replacive: food-feed, blood-bleed. Stress replacive ex; Import-impOrt The composite verb stems ex: to black mail. According to their semantic structure the finite verbs are divided into:

Here we’re to mention of the existence of the notional link verbs, this are verbs which have the power to perform the function of link verbs and they preserve their lexical value. Ex:The Moon rose red. Due to the double syntactic character, the hole predicate is reffered to as a double predicate (a predicate of double orientation)

This criteria apply to more specific subsets of words: ex: The verbs of mental process, here we observe the verbs of mental perception and activity, sensual process (see-look) The 2-nd categorization is based on the aspective characteristic. Too aspective subclasses of verbs should be recognized in English limitive (close,arrive) and unlimitive (behave,move). The basis of this division is the idea of a processual limit. That is some border point beyond which the process doesn’t exist. The 3-rd categorization is based on the combining power of the verbs. The combing power of words in relation to other words in syntactically subordinate positions is called their syntactic valency. Syntactic valency may be obligatory & optional. The obligatory adjuncts are called complements and optional adjuncts are called supplements. According as verbs have or don’t have the power to take complements, the notional words should classed as complimentive (transitive and intransitive)or uncomplimentive (personal and impersonal) |

(semi)functional verbs

Semi-notional and functional English verbs serve in a sentence as predication markers, i.e. they reflect the nature of the connection between the nominative content of the sentence and reality. The verbs of this lexical/grammatical subclass are subdivided into auxiliaries, modals, semi-notional verbid introducer verbs, and links.

2.2.1. Auxiliaries are the grammatical elements of the category forms of verbs. The list of English auxiliaries comprises the following verbs: be, have, do, shall, will, should, would, may, might.

2.2.2. Modals are the predication markers of the speaker's rational evaluation of the action expressed by the notional verb in the infinitive, such as ability, obligation, permission, advisability, relational probability, etc. English modals are: can/could, may/might, must, ought, shall/should, will/would, need, dare, used (to). Besides, the verbs have and be reveal modal meanings in certain contexts of their use. English modal verbs have a deficient system of grammatical forms, and that is why they are supplemented by such word combinations as to be able, to be obliged, to be permitted, to be likely, to be probable, etc., which are capable of expressing modal meanings as well.

2.2.3. Semi-notional verbid introducer verbs, as it follows from the term itself, are used with the verbids – mostly with infinitives and gerunds. They are not totally devoid of meaning and thus can be of the following semantics:

- discriminatory relational (e.g. seem, happen, turn out);

- subject-action relational (e.g. try, fail, manage);

- phasal (e.g. begin, continue, stop).

Semi-notional verbid introducer verbs should be distinguished from their grammatical homonyms in the subclass of notional verbs.

2.2.4. Link-verbs (copulas) introduce the nominal part of the predicate which can be expressed with a noun, an adjective, a nominal phrase or an adjectival phrase.

Like modals and semi-notional verbid introducer verbs, copulas are not totally devoid of meaning: their semantics is that of connection. English copulas are subdivided into pure links (to be) and specifying links, which can be perceptual (e.g.seem, appear, look, feel, taste), factual (e.g. become, turn, get, grow, remain, keep) or notional, which perform the copulative function preserving their lexical meaning (e.g. He lay awake; The sun rose red).

Auxiliary verbs

Auxiliary (or Helping) verbs are used together with a main verb to show the verb’s tense or to form a negative or question. The most common auxiliary verbs are have, be, and do. Auxiliary verbs, also known as helping verbs, add functional or grammatical meaning to the clauses in which they appear. They perform their functions in several different ways:

By expressing tense ( providing a time reference, i.e. past, present, or future)

Grammatical aspect (expresses how verb relates to the flow of time)

Modality (quantifies verbs)

Voice (describes the relationship between the action expressed by the verb and the participants identified by the verb’s subject, object, etc.)

Adds emphasis to a sentence

Auxiliary verbs almost always appear together with a main verb, and though there are only a few of them, they are among the most frequently occurring verbs in the English language.