Lecture Part I

.pdfWhere will you find art? The answer is, “almost everywhere”. We can experience it firsthand or secondhand. Museums are obvious places for face-to-face encounters with the real thing. However, art sheltered in museums is separated from the original context of its creation, whether dug from the site of a long-bured civilization, taken from a palace or religious building, or even removed from the living room wall of a wealthy collector.

One of the pleasures of studying art history is that it equips us to recreate the contexts, which we bring to bear on art wherever we find art: painted on the inside walls of caves, built as architectural sites all over the world, carved into rock, laid into floors, woven into special garments, installed in parks and malls, and now winking at us from computer screens.

The specialized vocabulary of art. The fundamental quality of art is visual and / or spatial. We need to “read” art and architecture in their terms.

Both two-dimensional art (paintings and works of graphic art, for example) and three-dimensional sculpture rely on descriptors such as representational, realistic, abstract and nonobjective to broadly categorize an artist’s visual approach to a subject. Representational art has subject matter that is recognizable from the natural world. Realistic art shows a high degree of imitation, or verisimilitude, of the actual object or subject. Abstract art simplifies and alters the appearance of actual forms (they can still be recognizable) for various purposes, often to suggest an essence or universality Nonobjective art deals with forms that lack any reference to the natural world. Also referred to as nonrepresentational or nonfigurative, it relies solely on the interplay of formal visual elements. Much modern art is nonobjective.

What are the formal elements? They include line, shape, mass and colour, as well as texture and composition.

Line can be drawn to define outlines, edges, and contours of forms and delineating shapes.

Shape is a two-dimensional form, an area on a flat plane.

Form is three-dimensional, occupying a volume of space.

Sculpture that is freestanding is a mass. So is architecture.

Texture and colour, which are activated by light, are the two other most important formal elements.

Colour is the effect on our brains of light of different wavelengths reflected off object. It is helpful to understand the meaning of three colour-related terms when you are reading about art – hue, value and intensity. Hue refers to the essential colour. Value refers to the degree of lightness or darkness of a colour. Intensity is the degree of a hue’s purity – the closer a colour is to the original rainbowspectrum hue, the higher its intensity and the brighter its appearance.

Artists working in two-dimensional arts are challenged with representing the real world of three-dimensionality on a flat plane. Artists have devised many pictorial strategies for suggesting space and objects in space, among them: vertical stacking of forms, the overlapping of forms, and the illusion of distance by gradation of colour from intense to pale.

Since the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century, the Western tradition has settled on scientific, or linear, perspective as the most satisfactory method. It is based on two observations. One is that forms look smaller the farther away they are and the other is that parallel lines appear to converge and vanish at the point of distance where sky meets earth.

A pond in a garden. Thebes, c. 1400 BC. The British Museum, London.

Fragment of a wall painting from the tomb of Nebamun, 18th dynasty. A pool full of ducks, lotus flowers and tilapia fish. Around the pool are papyrus, palms, sycomorefig, mandrakes and other bushes. In one corner is a tree in which the tree-goddess Hathor presents offerings to Nebamun and Hatshepsut, his wife.

The way an artist puts the formal elements together is called composition.

The word style used in art history is different from other, more general uses for the word. With art it describes the combination of distinguishing characteristics that imprint a work of art as the creation of a certain artist, or time, or place.

For as long as people have been making images, they have been devising and using pictorial symbols to represent abstract ideas or abstract dimensions of real objects.

Symbols are forms. Their meaning is an aspect of content. Form is what we see in a work of art, what is visible. What we interpret from the form is called content – the message or meaning of the work.

THE ANCIENT WORLD: Prehistoric art, Egyptian art, Ancient Near East, Aegean Art, Greek art, Etruscan art, Roman art.

Axial Gallery, Lascaux. 15,000-10,000 BC.

Dordogne, France.

Lascaux is the setting of a complex of caves in southwestern France famous for its cave paintings. They contain some of the most wellknown Upper Paleolithic art. These paintings are estimated to be 16,000 years old. They primarily consist of realistic images of large animals, most of which are known from fossil evidence to have lived in the area at the time.

The cave was discovered on 12 September 1940. By 1955, the carbon dioxide produced by 1,200 visitors per day had visibly damaged the paintings. The cave was closed to the public in 1963 in order to preserve the art. After the cave was closed, the paintings were restored to their original state, and are now monitored on a daily basis. Rooms in the cave include The Great Hall of the Bulls, the Lateral Passage, the Shaft of the Dead Man, the Chamber of Engravings, the Painted Gallery, and the Chamber of Felines.

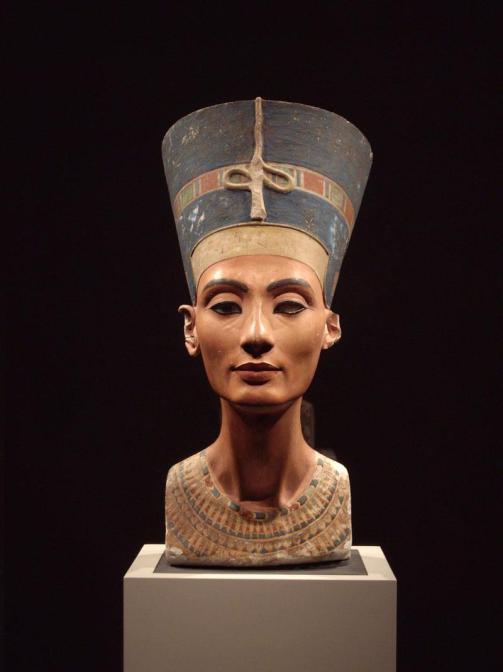

Queen Nefertiti, c. 1348-1336 BC. Limestone, h 48.3 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Pythokritos of Rhodes (?). Nike of Samothrace, c. 190 BC. Marble, h 244 cm. Musee du Louvre, Paris

THE MIDDLE AGES: Early Christian and Byzantine art, Early Medieval art, Romanesque art, Gothic art

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. Hagia Sophia, 532. Istanbul, Turkey

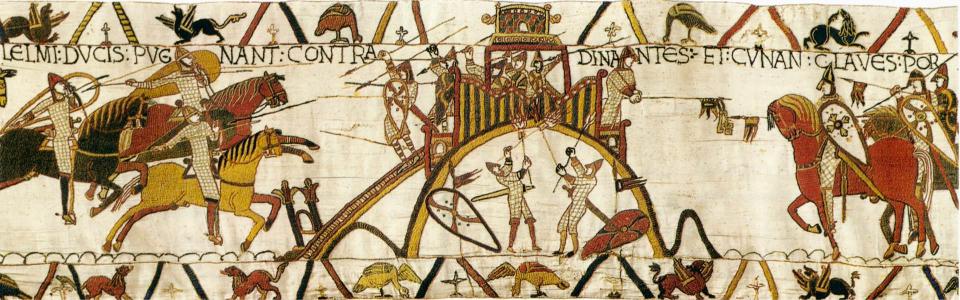

The Bayeux Tapestry, 1073-83. Embroidered cloth, nearly 70 metres long.

Depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England concerning William, Duke of Normandy and Harold, Earl of Wessex, later King of England, and culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The tapestry consists of some fifty scenes annotated in Latin, embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns. It is likely that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, William's half-brother, and made in England in the 1070s. In 1729 the hanging was rediscovered by scholars at a time when it was being displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral.

Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy.