WilliamsT

.pdfspirited essence of Weimar as opposed to the heavy, grotesque and macabre.’ (Peikert, 2010: 6)

Revising our understanding of German Expressionism’s role in film history is an important point for this thesis. Schüfftan would, in exile, come to be recognized as a cinematographer of the German Expressionist tradition. However, Menschen am Sonntag, Abschied, and in particular Ins Blaue hinein, demonstrate a markedly different, realist, tradition, one of observation and of humour. So, whilst the film could have been met with surprise by some upon its rediscovery, considering the film in the context of Schüfftan's other work of the period, it is a clear progression of his artistic development. For although Schüfftan is widely connected to the movement of Expressionism, and whilst his later work would adopt a number of Expressionist tendencies, he in fact only provided technical processes for the Expressionist films of the 1920s, and his first roles as cinematographer, Menschen am Sonntag and Abschied, represent a clear break away from this style.

Similarly, although not entirely through the same techniques of realism, Ins Blaue hinein seeks to represent the freedom of youth in this period, particularly through the young employee and his girlfriend. For it is a carefree attitude that dominates, firstly at the level of narrative, which sees the gang abandon both their jobs and their car, all done with a smile across their faces for the liberation it has granted them. But Schüfftan also reflects this in his approach to filmmaking. A sense of motion carries the film forward throughout, with almost constant uses of pans and tracks, most notably in the extended sequences which show the gang driving in the run up to the crash. Schüfftan shoots out from the car as it passes down the road, cutting to shots of the sky through the trees as the car drives, all done with a shaky hand-held camera, and all clearly filmed outside of the studio. It is the same sense of accordance between the liberation of the characters in the narrative and the liberation of the

71

camera itself that would be matched almost 30 years later by Jean-Luc Godard in À Bout de souffle/Breathless (1959).

The crash itself continues with this sensation of movement. There is a fast pace of editing, between point of view shots from the dog looking at the approaching car, point of view shots from the car, tracking quickly towards the dog, then a shot of the dog running backwards from the car. This was created by having the dog chasing the car whilst reversing, then playing the film backwards. We then see a tracking point of view shot from the car as it heads towards a tree trunk, eventually engulfing the frame in darkness. The aftermath of the crash continues the sense of confusion, created through an abundance of point of view shots. Camera movement continues as we see panning shots of a bouncing wheel, which cuts to a panning shot of a rolling hat. This is effectively a jump cut, for both objects fill the same space of the frame, both in pan movements from right to left. We then see the legs of a running man, before the camera finally rests in stasis and the crash is fully resolved.

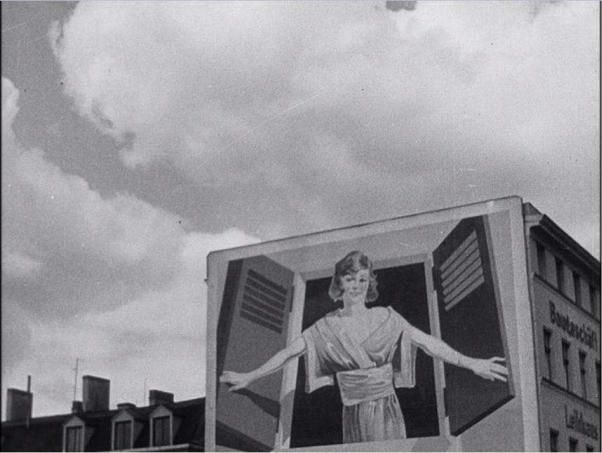

One further scene which displays the wit and invention of Schüfftan's directorial style occurs when the young employee runs from the car to pick up his girlfriend from her apartment. He runs past a large billboard to a fence overlooking the apartment windows. What follows is a classic shot-reverse-shot, albeit with a twist (see Figures 11-13). The first shot (Figure 11) sees the young employee looking up directly into the camera whilst whistling and calling for his girlfriend. In the reverse shot (Figure 12), Schüfftan then shows a large billboard which the young man has just passed, featuring a young woman in her dressing gown, who has just opened her shutters and is looming from the window. The third shot from this brief construction is from behind the head of the young man looking up to the window, where we see his girlfriend emerge from and wave in response, mirroring the image of the billboard (Figure 13). In the final image of this sequence, the girl is shown in her bathroom selecting

72

clothes for her trip. She holds a feminine dress against her body and looks into the camera lens, again reflecting the billboard image. However, she discards the dress and selects instead something more practical for her adventure (Figure 14). The second shot of this sequence is clearly positioned in response to the first, and comments on a number of issues such as consumerism, and even perhaps the scopophilic nature of the film camera. However, I would argue that the overriding discourse of these shots, in the context of the ‘liberated’ camera seen throughout the film, is to comment upon the constructed nature of the cinematic language, and so speaks of a desire towards a freer style of filmmaking, less burdened by the constraints of convention. It also represents a return to Schüfftan’s interest in dialectics, seen earlier in his experiments with footage from Metropolis.

Figure 11: Ins Blaue hinein. The young boy whistles up to his girlfriend’s apartment.

73

Figure 12: Ins Blaue hinein. The reverse shot. The responsive whistle we hear on the sound track from the girlfriend is matched by this image of a billboard.

74

Figure 13: Ins Blaue hinein. The next shot of this sequence shows the girlfriend waving from her balcony, matching the image of the billboard in the previous shot.

75

Figure 14: Ins Blaue hinein. The girlfriend matches the billboard girl’s gaze into the camera, before discarding the feminine dress and choosing something more relaxed for her adventure.

Ins Blaue hinein, particularly in the context of Menschen am Sonntag and Abschied, demonstrates the vibrancy of filmmaking during the Weimar cinema, beyond the perceived dominance of Expressionism. These three films in fact form a backlash of realism to the Expressionist style which had preceded it, and suggest the possibility of Schüfftan consolidating his abilities to become a strong directorial voice in the German film industry. Of course, the rise of the Nazi Party was to halt any possibility of an individual voice, particularly Jewish, within the German film industry, and was to send Schüfftan abroad where his directorial abilities were not proven to the studios, cementing his position as a cinematographer. The rediscovery of Ins Blaue hinein and its subsequent release on DVD in June 2011 by Criterion, as part of their Menschen am Sonntag package, provides an exciting

76

glimpse into the future that might have awaited Schüfftan, although, as we shall see, the development of his own unique style as a cinematographer is no less interesting.

The year of 1931 saw Schüfftan direct a second film, the Ufa production Das Ekel/The Scoundrel, which he co-directed with Franz Wenzler. Schüfftan also acted in his more usual role as cinematographer, alongside Bernhard Wentzel. In the film Max Adelbert plays Adalbert, an officious businessman who is no less officious in the treatment of his family. Adalbert is transformed however, through the influence of Quitt, his daughter's boyfriend. Much like Ins Blaue hinein, Das Ekel, with its comic tone, is far removed from the Expressionist style Schüfftan would come to be associated with. The film, a relic to Schüfftan’s lost future, has itself been sadly lost to history.10

It would seem that Schüfftan's next film occurred as a direct result of his time on Das Ekel. As Loewy (2005) has recounted, in March of 1931 when Das Ekel was shooting under the production management of Bruno Duday at Neubabelsburg, Anatole Litvak was working in the same studio directing Nie wieder liebe/Never Love Again, with the help of Max Ophüls as assistant director. Ufa had just granted Ophüls his first assignment as director, a short film intended to be packaged alongside other Ufa screenings, and to be made under the supervision of Duday. The project was the unusually titled Dann schon lieber Lebertran/I’d Rather Have Cod Liver Oil, which was made from a script by Emeric Pressburger and Erich Kästner (the scriptwriters of Das Ekel). It also boasted cinematography by Schüfftan and Karl Puth. The film, it seems, has been completely lost, however Ronny Loewy (2005) has undertaken the task of compiling all known information on the film. Loewy found that the twenty-two minute long film was made with a budget of over forty-six thousand marks, and

10Testifying to the disappearance of Das Ekel, following its discovery, Ins Blaue hinein has been heralded as Schüfftan’s only credit as director (Peikert 2010: 6).

77

that it was shot over six days during the first week of August, 1931. Loewy also reprints the following synopsis of the narrative, provided by Ophüls himself:

It's about children who, each evening, swallow their cod liver oil and say their prayers before going to sleep. One evening, when the room is quite dark, the youngest makes a rather daring prayer: he asks why it's always children who must obey their parents; wouldn't it be possible, once a year, to reverse the roles? The prayer goes up to Heaven: God is out, but St Peter is there, just about to fall asleep, and he asks himself why he, too, shouldn't grant a prayer. He goes into a machine room, full of complicated instruments, and exchanges the cards marked "parental authority" and "filial obedience." The child wakes up with a cigar in his mouth and dressed like a man. He gets up and sends his parents off to school. The parents have forgotten all they knew; they are incapable of the least effort and too awkward to manage any gymnastics; for their part, the children go to the office, have to cope with the tax collector and a worker's strike with all the attendant problems, and by the evening they are ready to demand that everything be put back as it was. . . . For three months they delayed releasing it because it wasn't really very good.

The most salient piece of information uncovered by Loewy however, is a recollection by Ophüls that, 'I was told years later that Eugen Schufftan [sic] was assigned with the order to take over immediately in the case of my failure' (Loewy, 2005). Whilst this was only a smallscale short film for Ufa, such a fact nevertheless shows the faith the studio held in the abilities of Schüfftan, who himself had had only brief experiences of directing. Of course such a fail-safe scenario was not in the end employed, which in hindsight was perhaps fortuitous for Schüfftan who (as we shall see) would go on to work with Ophüls again on numerous occasions in his subsequent career.

Schüfftan also worked on another Ufa production at this time, once again shooting alongside cinematographer Karl Puth on the film Meine Frau, die Hochstaplerin/My Wife, the Swindler,

78

under the direction of Kurt Gerron. The film was written by, amongst others, Phillipp Mayring, who had previously directed Schüfftan on Das gestohlene Gesicht, and starred Alfred Abel, the director of Narkose. The film was an early vehicle for popular actor Heinz Rühmann, who frequently adopted the role of male identity in crisis. In general, as Sabine Hake (2001: 95) has found, this meant the male in crisis displayed 'the markers of petit bourgeois mentality […] without any social consciousness.' Hake cites Meine Frau, die Hochstaplerin, which dealt with 'the problems of modern marriage' as such an example.

In this same year Schüfftan also collaborated with the director Lupu Pick, on the final film before his untimely death in 1931, the German-French co-production Gassenhauer/Street Song, from which a French version was also produced, entitled Les Quatre Vagabonds/The Four Vagabonds. Multi-language versions (hereafter MLV) of films were a common phenomenon at this time in Europe, and Schüfftan would come to work upon a number of other such projects. They arose as a response to concerns amongst the national cinema industries of Europe about the dominance of American cinema in their markets. This led many during the post First World War years to call for a pan-European production industry which could stem Hollywood’s continuing ascendency. The prospect of such an industry became known as ‘Film Europe’ (as opposed to ‘Film America’, before ‘Hollywood’ became synonymous with American cinema). Germany was by and large the instigator of attempts towards a Film Europe, and in particular one man, the prolific Ufa producer Erich Pommer. Pommer heralded Film Europe, and was responsible for the mutual distribution pact of 1924 between Ufa and the French distributor Etablissements Auberts. Pommer argued that, ‘European producers must at last think of establishing a certain co-operation among themselves. […] It is necessary to create “European films,” which will no longer be French, British, Italian, or German films; entirely “continental films”’ (Thompson, 1999: 60). Other similar mergers followed such as the Westi-Pathé agreement, however it should also be noted

79

that Germany, the powerhouse of Film Europe, was not averse to courting the American industry when it suited them, as was shown by the famous Parufamet agreement.

One major outcome of this German-led drive towards a Film Europe was the MLV method of production. MLV’s arose along with the birth of sound in the cinema, when any possibilities of a pan-European production scheme needed to negotiate the many language barriers of Europe. With an audience unimpressed by attempts at dubbing and subtitling, which were then seen as anachronous to the new possibilities offered to the medium by sound, the studios required a different approach. The MLV meant that a film would be shot simultaneously in any number of languages (most commonly German, French and English). Whilst the biggest polyglot stars of the film industry would sometimes act in every language version, other minor characters would most often be played by different imported actors. The illusion was to give the audience the impression that the film was the product of their own national industry, rather than a film produced in another country, by foreign technicians, which was then being circulated in different language versions across Europe.

MLV’s played an important role in the career of Schüfftan, as they offered him an early introduction to shooting with actors and sometimes technicians of other national industries, experience which would come in useful once he was forced into exile. In the case of Schüfftan’s first MLV experience, Gassenhauer and Les Quatre Vagabonds, both versions are sadly lost, however a contemporary review of the time by Rudolf Arnheim (of the German version) casts some insight. Arnheim (1997: 161) noted in particular Pick's novel innovations in sound: 'For instance, everyday instruments vary the refrain of a song: it sounds from the bellows of a prisoner through the prison walls, a vagrant whistles it, it penetrates the windows of a place of entertainment, spilling as muffled dance music into the street.' However, in spite of such techniques, ultimately Arnheim (1997: 161) found that whilst 'much is clever, not

80