WilliamsT

.pdf

Mocky would himself, when talking about the film some years later, describe it as ‘an accurate documentary on psychiatric homes.’50

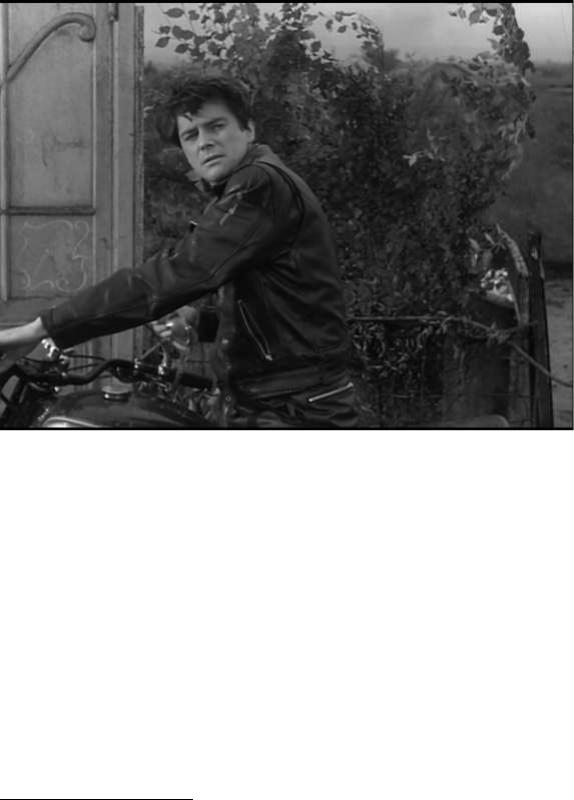

Figure 54: Jean-Pierre Mocky in La Tête contre les murs.

The contemporary setting of the film’s narrative in these opening moments is best set by the leather jacket worn by François (Figure 54). A list of contemporary influences including Marlon Brando in The Wild One (Laszlo Benedek, 1953), James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicolas Ray, 1955), Elvis Presley, and Johnny Halliday all signify not only his rebellious nature, but also the character’s sense of independence and freedom. This is supported by the freedom of Schüfftan’s camera movements in the opening sequence, reflecting the independence of the character, and placing him within an environment that is

50From an interview with Jean-Pierre Mocky on the Eureka Masters of Cinema DVD of La Tête contre les murs.

241

open and freeing. The independent spirit of François’s character is therefore immediately linked with an exterior and expansive space. This theme continues throughout the opening scenes of the film. When François visits his friends, they are enjoying a party on a boat, an interior space which is arguably more connected with the natural environment. We see for instance, one of his friends swimming in the dark waters, a natural extension of the deck of the boat. Conversely, when François visits his father’s house with the intent to steal some money, it is nighttime, and François traverses the exterior grounds of the mansion with ease. It is the interior of the house and its confinement which ultimately proves dangerous for François (not the dark or the nighttime), when his father enters, illuminates the room, and discovers his son’s crime. As we can see then, light also plays a key role in the construction of François’s character. Just as he is at home in the freedom of expansive spaces, he is equally comfortable in darkness, in which every space can become expansive, protecting those individuals within it. This is evident repeatedly in these opening scenes. The opening sequence of François on his motorbike occurs at dusk, with the subsequent scenes of François at ease with his friends occurring at night. It is the luminosity of his father’s entrance which finally consigns his son to his fate.

During the robbery François has burned sensitive court papers which his father, a judge, should never have removed from the court room. In order to save his own reputation, the father avoids a juridical course of action, instead having his son committed that night to a hospital for the mentally ill. Our first view of the asylum is from the car which drives

François to his fate. The scene opens with Maurice Jarre’s thunderous percussion sounds accompanying a striking point of view image, positioned from inside the moving car as it travels alongside the outer wall of the institution (Figure 55). Schüfftan’s lighting decisions for this image make it particularly remarkable. The shot is enveloped in almost complete darkness, except for a small beam of illumination representing the glare of the car’s

242

headlights cast against the wall. This is an anxious, uncomfortable image, an impression enhanced when considering the unnatural lighting positions used. The angle of the beam of light, cast upwards and across, could not possibly be the natural product of the car’s headlights. The realization of this fact functions to add a sense of the uncanny and to enforce the menacing nature of the shot. Such a sense of unease is partly the result of the tension in styles which has emerged, between the realism of the opening sequence, and a more stylized use of lighting seen subsequently. Kate Ince (2005: 71) finds in these moments the same despair and aesthetic menace found previously in film noir, and attributes this influence upon the film to Schüfftan:

Central to the creation of sinister noir atmospheres in [La Tête contre les murs] is the contribution of his German-born director of photography, Eugen Shuftan [sic.]. A contemporary of Fritz Lang’s, Shuftan worked in German silent cinema and extensively in Hollywood from the 1920s on, often on fantasy films or films featuring crime. Even more importantly, he was a leading director of lighting and photography for the poetic realists of late 1930s France […]. Shuftan worked, in other words, at the heart of the two European cinema movements that may legitimately be regarded as precursors of American film noir.

I would argue, however, that this is a simplification of the complex evolution of Schüfftan’s lighting style. It is perhaps more productive to view Schüfftan as the perfect companion to Franju for his combination of realism, and the more Expressionist influenced lighting techniques he developed only once in exile (which can in fact be linked back to Schüfftan’s study of Rembrandt). Furthermore, Ince overlooks Schüfftan’s American films of the 1940s, which as I have demonstrated in chapter two, more directly demonstrate how Schüfftan’s exilic style in Poverty Row influenced the major studios in terms of film noir. Furthermore, the high-contrast chiaroscuro lighting effects which Ince finds to be an influence from film

243

noir are not present throughout the film, for much of the film’s action takes place during vivid daylight in the asylum.

The examples Ince tends to cite as influenced by noir occur in settings outside of the asylum, although as I have argued, unusually this use of darkness at the start of the film (one which is tied to an expansive space, rather than the confines of darkness seen in traditional film noir) tends to provide a comfort to François. This generates a contrast with the bright illumination of the asylum once he is interned, which functions to provide greater horror by creating a sense of constant visibility and containment. It is a dichotomy between lightness and dark which is echoed by the dichotomy between nature and the built environment of the institution. Even in the case of this doom-laden image of François’s drive to the asylum, it is the uncanny use of light breaking through the darkness which makes the image so uncomfortable.

244

Figure 55: The asylum wall, strangely illuminated by the car's headlights.

In the subsequent shots to the opening sequences we see the car (transporting François) enter through the gates of Dury asylum. Only the tall gates to the asylum are lit by Schüfftan, granting them an imposing impression and leaving the rest of the location in darkness, suggesting the dominating power of the asylum walls as a point of containment (whereby containment is once more connected to light). From a shot within the grounds of the asylum we see the car pass through the gates, and the camera pans around to follow the path of the car as it drives down the long driveway towards the main asylum buildings. The streetlamps which highlight the driveway emphasize the length of the path and give contrast to the (freedom of) darkness which exists beyond the glow of the streetlamps.

245

Confinement

A fade-in from the driveway reveals our first glimpse within the asylum, in which the walls themselves become our immediate focus. Schüfftan’s camera fixes itself upon a bare white wall of the asylum, with a light fixture giving the only differentiation to this image (the light bulb itself is contained within its own glass cage). By focusing so immediately upon the plain white walls of the asylum, and the lights which will illuminate these walls throughout the film, Franju and Schüfftan explicitly present us with the correlation between luminosity and containment, and foreground the clinical, impersonal attitude which dominates the institution.

The shot continues as the camera slowly pans, following the path of a wire which runs down the wall from the bottom of the light. At the end of this downward panning motion a bed is revealed, within which a robed François begins to stir. François sits up, and is visibly unnerved as he orientates himself to his new environment. Schüfftan’s camera corresponds by slowly panning backwards to gradually reveal his surroundings. He leaves the bed and begins to walk down the ward, where we see a row of identical bodies, each lying motionless in their beds. What this shot truly reveals is the full clinical impersonal horror of François’s new environment. The camera moves from a plain white wall, which could be any wall anywhere, to eventually reveal an entire domain to which François has been admitted, a domain which envelops everything within it with the same plain white conformity evident in the opening image. François wears plain white hospital robes and is barely definable, thanks to Schüfftan’s lighting (a lack of backlight), from the plain white walls of the institution. So whereas Schüfftan would normally eagerly pursue a sense of depth within the image, through the use of backlights and shadows, here he has purposefully flattened François (via his robes)

246

into the walls of the asylum, suggesting the institutional conformity which is ascribed upon him, and the loss of his individuality.

We are then witness to François’s first experiences of the asylum, when he meets his fellow inmates over breakfast. François is first introduced to Colonel Donnadieu, whom he is told was ‘given shock treatment in 1918, relapsed in 1930 and 1945.’ Querying the relevance of the 1930 date, François learns that this occurred in Morocco, where Colonel Donnadieu was presumably stationed as part of the French protectorate. This had begun in 1912 and ended in 1956, giving Morocco independence once more only, a matter of years before production began on La Tête contre les murs. These comments link postwar and colonial trauma with madness, and suggest a subtext based upon another French Colonial operation, the war in Algeria which had been underway since 1954.

A high level of French censorship surrounded the Algerian war, a result of the state of emergency declared in 1955 and subsequently in 1958 (the latter as part of de Gaulle’s emergency powers). So rather than explicitly criticizing this hugely unpopular war, we could be justified in reading, through the references to the World Wars and colonial Morocco, a link between the heterotopic space of the asylum and this hidden war. Michel Foucault (2010) terms the psychiatric hospital a ‘heterotopia of deviation.’ He describes these spaces as ‘counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality.’ The asylum as heterotopia acts as a space beyond society, separating those who deviate from the functioning society, and therefore also acting as a space of censorship. The unknowable, unquestionable war in Algeria therefore links to the unknowable madness of the inhabitants of the asylum, in particular Colonel Donnadieu.

247

The reference to the shock treatment enacted upon Donnadieu can also be seen as an allusion to the Algerian crisis, and the ‘clean’ torture tactics which were being widely employed. In fact, electrotorture was a particularly French brand of persecution, used by the police as early as 1931. As Darius Rejali (2009: 407) explains, ‘the French in particular pioneered the dominant form of electric torture for forty years, torture by means of a field telephone magneto.’ Such techniques of ‘clean’ torture were widely employed by the French in the Algerian war. Parallel to this, ‘clean’ treatments dominated mental health care during the twentieth century, barbaric treatments of the mentally ill, including shock therapy and lobotomies, which functioned to nullify the personality of a patient. It was these treatments in particular that had contributed to the anti-psychiatry movement, and wider calls for deinstitutionalisation. Both the army and the asylum employed these ‘clean’ techniques as tools of control and order.51 Adam Lowenstein (2005: 43) has drawn similar parallels between the tactics of torture employed in Algeria, and the vision of the medical environment in Franju and Schüfftan’s subsequent collaboration, Les Yeux sans visage.

Allusions to war were an established method of argument within the movement of deinstitutionalization, particularly during the postwar years, with those returning from the trauma of war bringing to public attention the widespread existence of mental illness. Accompanying the photo-exposés that had so aided the cause of deinstitutionalization was a discursive link between war trauma and psychiatric treatment. Erb (2006: 48-49) has noted that comparisons were made to concentration camps, to the Nazi euthanasia programme, and to restraint methods as torture. These comparisons were made to cause outrage, however Franju links the asylum space to more recent censored traumas, enacted by France.

51Kristin Ross (1999) has discussed the clean torture techniques employed in Algeria as a parallel with the modernization taking place within French homes of the 1950s. Such parallels, largely involving clinical kitchen and bathroom spaces, can clearly be extended to the clinical space of the asylum.

248

These issues of an ‘unseen’, censored war are also articulated in the film in the form of the next patient introduced to François. He is described as ‘a rare specimen who pretends to be blind. He’s only blind so he can see clearer.’ These lines are suggestive of the censorship clouding the reality of Algeria, and point once more to a discursive subtext of the film. For although it could not be clearly outspoken in the film, this specific conflict is, nevertheless, apparent in numerous ways through parallels drawn with the patients of the asylum.

Similar parallels with postwar trauma, although not with Algeria, were made in the source novel by Hervé Bazin, upon which the film was based. The novel, published in 1949, was positioned to speak to a culture still entrenched in the traumas of two World Wars. This is apparent even before Bazin’s narrative begins, in the dedication of the book to Milo Guyonnet, who is described as a ‘volunteer in the Great War, patient at Saint-Maurice and at Villejuif (Henri-Colin); captain in the Liberation Movement, in which he met his death in

1944.’ So as we can see, Franju presents a film which acts not only as a critique of the asylum system in France, but which also, through closer reading, offers a subtext that highlights the many traumas which were currently being enacted in Algeria, which could not be explicitly spoken of in France. And as we shall continue to see, this prime text and its subtext – which both function to criticize institutional structures – are supported by the lighting choices of Eugen Schüfftan, whose own personal traumas of exile, including a brief period spent in a French concentration camp, can be read into this tale of repression and anxiety.

Such a reading is further emphasized when considering the generational dichotomies which exist within the film, most notably those between François (Jean-Pierre Mocky) and his father (Jean Galland), François and Dr. Varmont (Pierre Brasseur), and between the two doctors of the asylum, Varmont and Dr. Emery (Paul Meurisse), a point to which I shall now turn. By

249

sectioning his wayward son at the Dury asylum, François’s father effectively passes the baton of patriarchy to another institutional order, the asylum (rather than the family). Let us not forget that François’s father is a judge, part of another institutional order, and it was François’s interference with this institution, the burning of court papers, which resulted in his internment at Dury. The absence of François’s father from the asylum does not however signal the dissolution of the patriarchy. Rather this role is replaced by another equally stern father, Dr. Varmont. Tellingly, François’s father and the doctor act as friends when the father visits to assess his son’s progress. This explains how François came to be sectioned so easily, without the involvement of the police. Dr. Varmont’s is not a nurturing patriarchal role, but rather one which attempts to instill in François conformity to the institutional order. It is a doubling of the dose of patriarchy, one which is suggestive of the symbolic patriarchal return of de Gaulle to power, complete with his greater Presidential authority and a tightening of civil liberties.

The dichotomy between these two generations and their attitudes to this order is served well by Schüfftan’s lighting, and is particularly evident during the scene in which Dr. Varmont and François converse following the patient’s first escape attempt. The scene is structured as a typical shot reverse shot between doctor and patient, the juxtaposition of which makes apparent the different lighting techniques employed by Schüfftan for each character (see Figures 56 and 57). Firstly, there are differences in framing between the two characters. François is viewed in close-up, whereas we are positioned slightly more distanced from Varmont, in a medium close-up, creating a greater emotional connection between the spectator and François. There is also a notable flatness of tone in the image of Varmont, with his white hair and his white hospital robes blending into the plain wall behind him. Varmont casts no shadow upon this rear wall, generating a lack of depth in the image. In contrast is the shot of François, whose dark hair and costume set him apart from the plain white

250