WilliamsT

.pdf

bedclothes. He also leaves a shadow, which defines his own image against that of his surroundings. Schüfftan has created this effect by lighting François from the right hand side of the image, using little fill light on the opposing side of the face, thus casting a dark shadow which differentiates him from the asylum bed. The meanings produced by these lighting choices and their juxtaposition in this scene position the doctor as part of the institutional framework, by literally blending him into the walls of the asylum, and François as someone who resists this institutional order, and whose place does not exist within it.

Figure 56: Dr. Varmont looks down on his patient.

251

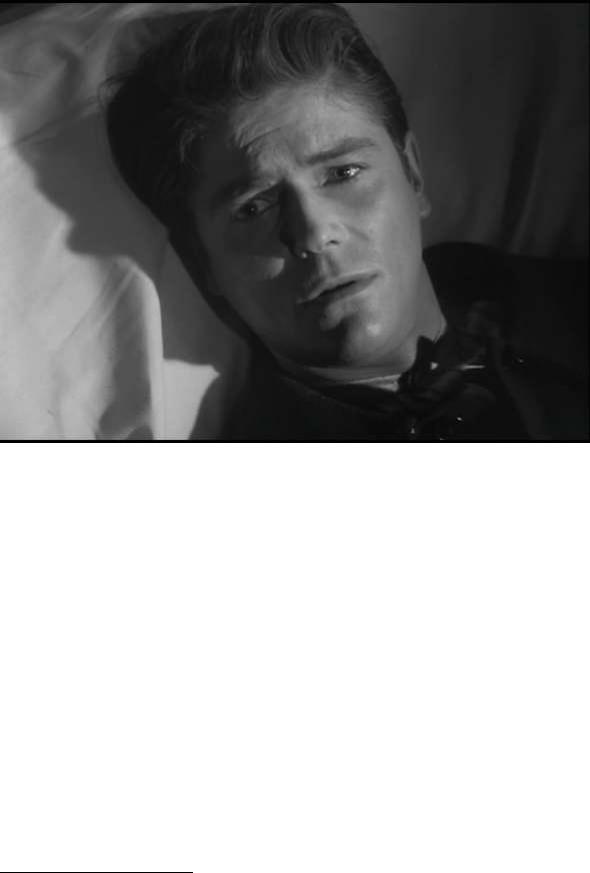

Figure 57: Mocky’s performance is enhanced by Schüfftan’s use of an eyelight.

Schüfftan’s lighting choices also add emotional depth to the scene, generating sympathy for

François, and leaving the spectator aghast at the impersonal nature of his incarceration. This is achieved through Schüfftan’s use of an eyelight.52 Its use is quite evident in the image of François, enhancing the emotion of his performance. In stark contrast to this is the shot of Dr. Varmont, who enjoys no such eyelight. Another cinematographer, John Alton (1995: 104), described the effect of not using an eyelight: ‘The result is dull eyes, which look like a dark night, or a shut door. […] In place of a brilliant eye, there is a dark hole, an empty socket. This gives the person in the picture the expressionless cold look of a statue.’ This is

52 An eyelight is an additional reflector light positioned in such a way so as to reflect in the eyes of the subject. Although not bright enough to add to the exposure of the image, it serves to add emotional depth and to enliven the face in such shots.

252

the effect created by Schüfftan’s refrain from employing an eyelight for the doctor, which is further enhanced by his fixed stare directly into the lens of the camera, through the lenses of his own glasses.

Examining the scene further, the contents of their discussion enforces this reading of

Schüfftan’s lighting. Firstly, Dr. Varmont, representing the old-style of treatment, clarifies to François the reason he has been incarcerated, citing the destruction of the (institutional) documents as the primary cause. He says, ‘You burnt documents that didn’t belong to you. A pointless act of destruction. Why did you do that? That “why” is what differentiates a doctor from a judge. If you can answer that question, you’re free to go. If you cannot, you leave me no option but to draw my own conclusions.’ Here we see Dr. Varmont attempt to differentiate himself from François’s father, the judge, perhaps in an effort to communicate with him more rationally. However, his differentiation is made rather inconsequential by his insistence on ‘why’, on the necessity to ascribe reasons for actions to a codified social order, and the reliance upon cause and effect, upon which both he and the judge rely.

The discussion quickly turns to François’s father, with the patient explaining, ‘I wanted to hurt him, destroying what was dearest to his heart’, undoubtedly the patriarchal order and the legal institution. From here the dialogue addresses the reason for François’s hatred of his father, and he begins to describe the events surrounding his mother’s death. He explains how as a young child of eight he witnessed from his bedroom window his father arguing violently with her near the pond. The father would later explain to François that his mother had committed suicide by jumping in the pond, and was alone at the time, a fact which François knows to be untrue. Having sedated François, silencing his revelation, Varmont leaves the room whilst saying to the unconscious patient, ‘only sick people dream of escaping. I don’t try to escape, do I?’ This suggests that those who don’t conform to the institution and dream

253

of a freedom beyond societal boundaries must be sick, whilst the sane can only be deemed such as long as they function within a strict adherence to the structures of society. Having left François’s room, Dr. Varmont fully dismisses the patient’s shocking disclosure about the actions of his father with the Freudian dismissal to another doctor, ‘a prime example of father hatred.’

The content of this discussion between doctor and patient reemerges later in the film, when

François’s father visits the hospital to see his son. Dr. Varmont queries François’s father about the events surrounding the mother’s death. When he explains that it was suicide, Varmont asks about the inquest which must have occurred, to which the father responds,

‘questioning, an autopsy, no suicide case ever escapes slander.’ There is a subtext within these discussions which suggests that the father may have been able to cover up his wife’s death, precisely due to his standing as a judge, and his position within the institutional order. An act reminiscent of the great corruption which has, years later, occurred between the father and the doctor: the covert admission of François to a mental institution.

This generational divide between the doctor and the young patient (reflected by the dichotomy between freedom and the institution) forms a critique of the asylum system and a desire to reform it from the stagnant practices of the old guard. Such a discourse equally forms a comment upon the Algerian war, previously alluded to by the story of Colonel Donnadieu. The notion of freedom and individualism is represented through the generation of post-war youth, which is contrasted with an older generation that had been active in such conflicts, and whose submissiveness to authority resulted in part in the collaboration with a German enemy occupier. The representation of this older generation through Varmont and François’s father is one which conforms to the governing institution, and to the state.

Therefore, through this mode of representation, they also stand for collusion with the crimes

254

and censorship enacted by the French state during the Algerian war. As Adam Lowenstein (2005: 43) has commented, ‘because the Algerian War goes to the very heart of French national identity […], it makes sense that it was understood at the time through the lens of that other recent battleground for French identity, the Occupation.’ However, the question emerges why François does not refer to his military service, for he would have been called up to serve at age 18. In light of the generational dichotomy in the film, it is possible that François’s wayward, nomadic lifestyle had seen him skip military service, although this is never made clear. This is the true crime for which the older generation, in the form of his father and Dr. Varmont, seek to punish him. Consider also the role of the younger physician of the asylum, Dr. Emery. Emery’s youth endows him with a freedom from the institutional modes of the asylum entirely at odds with Dr. Varmont. Emery, in his youth, stands for a belief in the deinstitutionalization of patients, thoughts which were soon to be articulated by the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s. As Erb (2006: 50-51) has noted, this dichotomy is similarly present in other films that tackle the treatment of the mentally ill, such as The Snake Pit. This film reflected the reality of the divide within the American Psychiatric

Association, which included a group known as ‘Young Turks’ who sought to reform the system.

Freedom and Confinement

Such a dichotomy between freedom and confinement goes beyond the desires of Dr. Emery to free his patients from the constraint of the asylum walls, and becomes a major part of the film’s narrative during the final scenes, when François has successfully escaped from the institution and attempts to navigate himself through the nightlife of Paris. The cityscape acts as a third space, offering neither the complete freedom of the expansive landscapes from the

255

early scenes of the film, nor the abject confinement of the asylum walls. An early establishing shot of the location soon highlights the many differences between the asylum and the city. Bright lights and plain walls have been replaced dark corners, only permeated by the glare of neon advertising lights (synonymous with Modernism53) (Figure 58). By acting as a Modernist space, the city is also a space representative of the social order, and thus no safer an environment for François than the asylum. François has escaped to darkness, however this is no longer the comforting darkness of the countryside, but rather a darkness in which lurks the full horrors of film noir. François enters a billiard parlour and finds his way through the poolrooms to a gambling hall beneath the main building, where crowds of people watch and bet on roulette.

53Neon lighting was a turn of the century invention, which came to full prominence in the 1920s and 1930s thanks to the Frenchman Georges Claude. As Lucy Fischer has explained in her essay ‘The Shock of the New’ (2006: 19-37), this electrification of lighting is central to an understanding of modernism, and to an understanding of film as an essentially modernist art form.

256

Figure 58: Our first view of the city space.

Such images, of the verticality of the city exteriors, and of the introspective nature of these hidden city spaces populated by the ne’er-do-wells of society, are central amongst

Schüfftan’s oeuvre, and demonstrate how crucial this particular technician can be considered to the overall aesthetic of the city in this film (which would be fully realized in his later films, addressed in chapter four). Present is both an impression of the city as a Modernist space, seen in Schüfftan’s work as early as Metropolis, and the dark visuals of the city, evident in

Schüfftan’s reinvention of Expressionism with a more painterly approach, perfected during his time spent in exile. These images of the city in La Tête contre les murs also prefigure an aesthetic progression in Schüfftan’s career, seen in his New York films of the 1960s. Here

257

Schüfftan has created a view of the city as more threatening to François than even the asylum itself, enveloped in a darkness that is no longer comforting to him.

François visits his girlfriend Stéphanie and reveals how uncomfortable he feels in the city by discussing plans to flee. The city and the asylum therefore offer different experiences to François, but the same conformity, the same loss of individualism when faced with societal constructs. The Moral Treatments propagated by Philippe Pinel (which are followed in the film by Dr Varmont), were after all centred on the prospect of reorienting patients to society through the totalizing replication and application of the institutional order within an asylum. This filmic discourse spoke to wider societal mistrust of the asylum system in France, which included calls for deinstitutionalization, and acts in anticipation of the views Michel Foucault (Madness and Civilzation, 2006), who would soon vocalize these issues as part of the antipsychiatry movement in the 1960s. The asylum functions to treat patients by creating a microcosm of society, which is then extrapolated in the film by maximizing that microcosm to the full city space in the final scenes. The failure of this approach is made most explicitly in the film through the suicide of Heurtevent. In this sense we can see a clear link back to the critiques made by the German Modernist theorists of the Frankfurt School in the 1920s of mass society and the inherent loss of individualism in the city.

The final realization of François’s true loss of freedom in both the asylum and the city space arrives in the closing moments of the film. When two asylum workers attempt to locate François by visiting Stéphanie, he decides he can remain no longer, and that he cannot subject Stéphanie to his life on the run. Slipping out of her door, he makes his way down the stairs of the building. This is captured in stark chiaroscuro lighting (Figure 59). Schüfftan casts a strong level of light from the centre of the stairwell, sending the long shadows of the

258

stair rails and François across the wall. This creates a disconcerting image in which the bars of the stairwell against the shadow of François form a reminder of his perpetual confinement.

The two asylum workers await their prey at the bottom of the staircase, grabbing François out of the dark in an image shot from Stéphanie’s point of view, looking down from the top of the stairwell. Grabbed from either side, François screams and looks up directly towards the camera in a plea for help. François is then dragged from the building and taken to a car waiting outside to return him to the asylum. The final shots repeat that same unusual image of the car’s headlights against the outer walls of the asylum grounds, followed by the car driving through the asylum gates. It is an identical recurrence of the shots from François’s first admittance to the asylum near the start of the film, and recalls the horror created in the final shots of Dead of Night (Basil Dearden et al., 1945), when the audience reaches the terrifying realization that they are bound up in a repetition of events. Kate Ince (2005: 72) similarly ascribes to the darkness of the opening and closing scenes of the film ‘a circle of confinement characteristic of the most claustrophobic and doom-laden film noir.’ Erb (2006: 58) describes the denouement of therapy narratives from this period as characterized by a

‘recovery of origins moment,’ and a ‘purging of madness.’ La Tête contre les murs, and

Lilith, both revert this trajectory. They show sane men entering an asylum to be, by the end, conditioned as insane. This brings to mind the ‘snake pit’, the horrific ‘therapeutic act’ which lent its name to Anatole Litvak’s film of 1948. It was thought that throwing a patient into a pit of snakes would shock them back into sanity. In the case of La Tête contre les murs and Lilith, the sane are shocked into insanity.

259

Figure 59: François heads down the stairs against Schüfftan’s chiaroscuro lighting.

It is worth recalling here that this discussion of La Tête contre les murs began by addressing the documentarist aspects of Schüfftan’s opening shots of the film, as a way of grounding the film in a real and contemporary setting. However, these final moments, with their explosion of horror, are at complete odds stylistically with those opening scenes. Schüfftan, with his origins in realism on Menschen am Sonntag, and his incorporation of an Expressionist aesthetic later in his career on films such as The Robber Symphony (Fehér, 1935), is perfectly placed to employ both of these disparate styles within a single film. His lighting takes us, across the course of the film, from a sense of the real and of the now, into a nightmarish realm of injustice and horror, made all the more terrifying by the film’s roots in reality.

260