WilliamsT

.pdfunbelievable and unbelievably awful picture' (Youngkin, 2005: 80). Beyond that little is known of the film. Nevertheless, the personal story of German-Jews involved in the production of Unsichtbare Gengner continues, with the comments made by Goebbels in his speech soon realized when a boycott of German-Jewish filmmakers was implemented on 1 April 1933.

Schüfftan and his Jewish colleagues of Unsichtbare Gegner clearly could not return to work in Germany under such circumstances, and the Austrian industry was quickly tightening up due to its reliance on German production funds. As Horak (1996: 376) has noted, there was even 'a Jewish boycott [...] more or less in place in Austria as early as 1934.' Politically, whilst the Austrian government was officially anti-Nazi, and had even banned the NSDAP on 19 June 1933, antifascist organizations were similarly prohibited (Palmier, 2006: 140) The situation was such that the Austrian writer Karl Kraus described to Bertolt Brecht the arrival of German émigrés in Austria as rats boarding a sinking ship (Warren, 2009: 38). Many émigrés opted to flee straight from Austria to America. However, the option chosen by Schüfftan and a number of others was France, undoubtedly picked for the strength of its industry, its proximity, and the vocal support in the French press for those Jews of the German film industry who had been ousted by the Nazi regime (Horak, 1996: 376).

France

Schüfftan was a known entity in France when he emigrated there in 1933, partly due to the reputation of his name, associated with his invention for Metropolis; partly due to the groundbreaking international success of Menschen am Sonntag, and also due, in part, to the numerous German-French co-productions upon which Schüfftan had worked. Nevertheless, the status and trust Schüfftan had built upon for his work as a cinematographer in Germany

91

was not present in his new home, and so the early part of Schüfftan's career in France tended to rely upon collaborations with other émigré filmmakers. This was true of Schüfftan's first film in France, La Voix sans visage/Voice Without a Face (1933), directed by the Austrian émigré Leo Mittler and starring the famous French tenor Lucien Muratore, in the role of a singer who has been accused of murder (Fryer and Usova, 2003: 151).

Similarly with his next film, Du Haut en bas/High and Low (G.W. Pabst, 1933), Schüfftan was reunited with a number of émigrés with whom he had previously worked in Germany, most notably the director G. W. Pabst and the set designer Ernö Metzner from Die Herrin von Atlantis, as well as Peter Lorre, directly on the back of Unsichtbare Gegner. Another important figure with whom Schüfftan was reunited on Du Haut en bas was Jean Gabin, who had acted in Coeurs joyeux, and was still some years off the mega-stardom he would enjoy following La Bandera (Julien Duvivier, 1936). Du Haut en bas, based on the play by Leslie Bush-Fekete, is essentially a comedy of manners set around the courtyard of a Viennese community and its various unique occupants, including Jean Gabin as a soccer player.

In accordance with the genre and the light-hearted nature of the film, Schüfftan keeps the film very brightly lit, using strong baselights, keylights and sidelights to create an evenly lit set, avoiding high contrast and strong shadows. This also fits with the setting of the film – a bright Viennese day, which pervades both interior and exterior aspects of the courtyard. This approach by Schüfftan also functions in alliance with Pabst's very mobile camera style, allowing the camera to move around the well-lit space without the movements of the shadows and the contrast needing to be similarly choreographed. Such movements are described by Koch (1990: 154) as, ‘The superbly graceful camera of Eugen Schüfftan.’ Certain shadows are however created – Schüfftan employs diffused light to cast gentle indistinct shadows, and in the exterior scenes, masques are used to create the effect of shadows caused by the leaves

92

of the trees. This functions to add interest to the frame, without overpowering the image with a stylized use of lighting.

Such an approach to lighting is similarly true of close-ups, which are well lit from both sides of the face, with back lighting used to distinguish the subjects from the background. Such an approach is markedly different to how Schüfftan would choose to light Gabin when they would reunite some years later. This is in part because, as Gertrud Koch (1990: 153) points out of Du Haut en bas, 'The camera does not make Gabin into an erotic object' (see Figure 16). It is worth noting that this is largely because, at this time, Gabin was not yet the mythical icon of Poetic Realism he was set to become, a point which Koch fails to make in her reading of the film. For although Gabin, in Du Haut en bas, is constructed as a workingclass hero, and is fetishized by many of the females in the courtyard precisely because of this fact, it is only later that the status of Gabin as an actor would largely affect the lighting choices made, as well as the mood of the film, allowing Schüfftan to codify him in more enigmatic terms.

93

Figure 16: Jean Gabin in Du Haut en bas.

Schüfftan's first project of 1934 was an adaptation of Henri Bataille's play, Le Scandale/Scandal. This was directed by France's wunderkind of the 1920s avant-garde, Marcel L'Herbier, who was now enjoying a string of successes based on literary adaptations. According to L'Herbier, his recipe for success in such adaptations was an emphasis of the cinematic over the theatrical (Andrew, 1995: 134). The scandal in question of this particular adaptation's title is the adultery committed by Charlotte against her husband Maurice, with the roguish Comte Artanezzo. The wife's unfaithfulness comes to light when a ring, which had been given from husband to wife, and then from wife to lover, resurfaces after Charlotte had claimed it lost.

94

Schüfftan's contribution to Le Scandale was brief, shooting only the studio scenes during the first week of filming (Asper and Meneux, 2003: 153). Cinematography duties on the rest of the film were then completed by Christian Matras, who would later find success collaborating with Max Ophüls. This brief experience did nonetheless prove important for Schüfftan, as he would reunite with L'Herbier in 1937 for Forfaiture/The Cheat. Although Schüfftan provided only a minor contribution to Le Scandale, it is perhaps also worth noting that the film proved successful with critics, being described as 'of high calibre' and 'worthy of serious thought' (Matthews, 1934).

Schüfftan's next film saw him reunited with fellow émigré Robert Siodmak, with whom he had started his career as cinematographer in Germany, on Menschen am Sonntag and

Abschied. The film, La Crise est finie/The Slump is Over, is a musical comedy about a theatrical troupe which disbands, leaving half of the troupe resolved to mount their own performances in Paris. However, financial difficulties prove a far greater barrier than anticipated. Alastair Phillips (2004: 85-86) has described how the film, similarly to a number of other French films from this period, seeks to discuss class-based oppositions, and demonstrates how this is represented through the mise-en-scène (see Figure 17). In terms of lighting, Phillips describes how Schüfftan lights the scene in which the troupe lure and capture Bernouillin (who has been responsible for sabotaging their operation) in the theatre. Phillips (2004: 86) notes that the lighting suggests 'the darkened and shadowy sense of menace', and that 'Schüfftan uses a minimum of identifiable light.' In general, however, Schüfftan’s lighting choices predominantly accord to the light-hearted tone of the film. This moment is perhaps the briefest indicator towards Expressionist tendencies Schüfftan would soon begin to develop.

95

Figure 17: Bernouillin trapped in the theatre in La Crise est finie.

Great Britain

At this time in 1934 Schüfftan travelled to England to offer his expertise to a national industry also benefitting from the talents of a number of émigrés. The story of the influence played by European émigrés in the British cinema is an emerging one (Bergfelder and Cargnelli, 2008), and one to which I will add Schüfftan's brief role. Beyond simply professional opportunities, it is possible that Schüfftan chose Britain because his daughter, whom Schüfftan visited in London on numerous occasions during the 1950s, was already residing in the country. However, on the whole, Britain was not entirely welcoming to refugees of Nazism. It had accepted a mere 4,500 exiles by 1937, and was not a particularly

96

sought out destination, due to the economic crisis the country was suffering, meaning that exiles were even less likely to be awarded work permits (Palmier, 2006: 149).

In terms of the film industry, permits were not easily come by for émigré technicians in the British film industry. Tim Bergfelder (2008: 3) has noted the attempts dating from the early 1930s by the Association of Cine-Technicians 'to block and prevent the employment of foreigners in British studios (a policy that was primarily aimed at continental technicians).' Consequently Schüfftan could only get a permit to work in Great Britain in connection with the Schüfftan Process, which had been bought by British National and was first used in the country on Madame Pompadour (Herbert Wilcox, 1927), before coming to popular usage with Alfred Hitchcock’s Number 17 (1928) and Blackmail (1929) (Low, 2004: 246) (Bock, 1984: Schüfftan entry). These permit restrictions remained in place for much of Schüfftan's career.12 His permit in place, Schüfftan's first film in Great Britain was Irish Hearts with the Irish director Brian Desmond Hurst, who had learnt the business under the tutelage of John Ford. The film, which is believed by some quarters to be the first Irish sound feature, is the story of a surgeon who fights a typhus outbreak, whilst at the same time fighting his own feelings for the two women in his assistance (McIlroy, 1994: 28). On Schüfftan's part, the film was praised in a review of 1936 for its 'beautiful photography' (Glancy, 1998: 63).

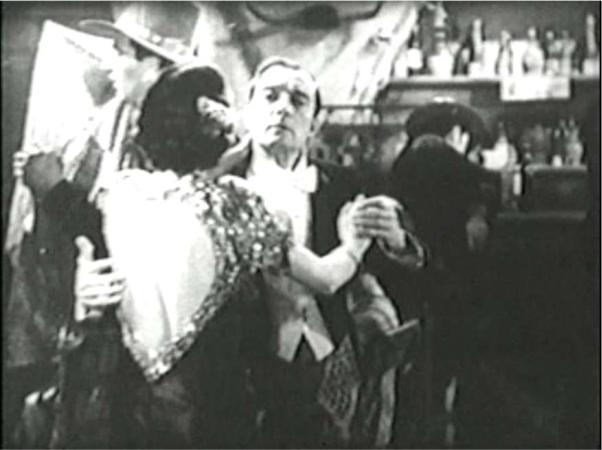

Schüfftan's second project in Britain was widely considered as an unmitigated disaster as an exercise in filmmaking, but would prove significant to the cinematographer’s later career development. The film was The Invader (Adrian Brunel, 1936, also known as An Old Spanish Custom), a low budget vehicle for Buster Keaton, who was hoping to launch a comeback. However, it was not Keaton, but rather his co-star Lupita Tovar who was to impact upon Schüfftan's life. Tovar had recently married the producer Paul Kohner, with

12This is confirmed by Schüfftan in a letter to Ilse Lahn of the Paul Kohner talent agency, dated 13th November, 1956.

97

whom she had first worked on La voluntad del muerto (Enrique Tovar Ávalos, 1930), the Spanish language version of the Hollywood horror The Cat Creeps (Rupert Julian and John Willard, 1930). When Kohner was to settle later in America he would set up a talent agency with the primary aim of representing the interests of émigré talents in the industry. It was Kohner who was to act as Schüfftan's agent throughout much of his Hollywood career, and it was upon The Invader that this relationship was first established. Fittingly, their first meeting on the set of The Invader was recalled by Schüfftan as a fond memory in response to a letter from Paul Kohner congratulating Schüfftan on his success at the Academy Awards in 1962.

Figure 18: Buster Keaton dances with Lupita Tovar in The Invader.

Schüfftan's third British project, The Robber Symphony, proved to be a particularly transnational affair. Filmed during 1935, The Robber Symphony was the brainchild of

98

Austrian director Friedrich Feher, and was conceived as an experiment in film music, whereby the action would be set to a pre-composed score (composed by Feher himself). The crew, besides Schüfftan as cinematographer, included Robert Wiene as producer, whom Feher had met on the production of Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari/The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(Wiene, 1920), and Ernö Metzner, the émigré set designer who had already collaborated with Schüfftan. These continental artists all combined their talents on The Robber Symphony, and a French language version titled La Symphonie des brigands, filming in studios in London, and filming on location in Mer de Glace, Nice, and elsewhere on the Côte d'Azur (Ede, 2008: 120).

Once again, Metzner has garnered critical attention for his set design (Ede, 2008), however, Schüfftan's role has been sidelined in comparison. Ede (Ede, 2008: 199) notes a surprising Expressionist style in Metzner's set designs, unusual for the artist. However, it is suggested that this influence is produced by Feher and in particular Schüfftan, 'well known for his love of chiaroscuro lighting.' It is important to stress here that this description of Schüfftan's early style is a misrepresentation, most likely propagated through the association between Schüfftan and his special effects process for Metropolis. As we know, Schüfftan did not start work as a cinematographer until 1929 on Menschen am Sonntag, and as we have seen, this and his other early films were a strong reaction against the Expressionist style of the 1920s. In fact, The Robber Symphony is one of the earliest examples of Schüfftan adopting an Expressionist style (see Figures 19 and 20). So in fact, it is an approach he adopts once he is already in exile. Nonetheless, it would become a style which he developed throughout the rest of his career in Europe and America, long after the close of the Expressionist movement of the 1920s, and his own initial reaction to it. So, if neither Metzner nor Schüfftan had (until this point) developed an Expressionist style, we must look for a cause for this aesthetic in The Robber Symphony, beyond simply the influence of Wiene and Feher. One particular cause for

99

this use of Expressionism could well be the particular stylistic trait of the film, being an experiment in setting a film to a pre-existing score. In this reversal, the set designer and cinematographer attempt to match the mood created by the score, through the particulars of their own art. In this sense, we can argue that Schüfftan's long association with Expressionist effects and chiaroscuro lighting came about as a result of his working with Feher on this film, and in particular the impact of Feher’s preexisting musical score. However Schüfftan may have been influenced to adopt such Expressionist tendencies, it is clear that this stylistic trait only emerged once in exile.

Figure 19: Dramatic flashes of light in The Robber Symphony create the effect of lightning.

100