Accounting For Dummies, 4th edition

.pdf

300 Part IV: Preparing and Using Financial Reports

and so on. Also, the manager needs a list of the various liability risks of owning and using the fixed assets. The manager has to decide whether the risks should be insured.

Accounts payable

As you know, individuals have credit scores that affect their ability to borrow money and the interest rates they have to pay. Likewise, businesses have credit scores. If a business has a really bad credit rating, it may not be able to buy on credit and may have to pay exorbitant interest rates. I don’t have space here to go into the details of how credit rankings are developed for businesses. Suffice it to say that a business should pay its bills on time. If a business consistently pays its accounts payable late, this behavior gets reported to a credit rating agency (such as Dun & Bradstreet).

The manager needs a schedule of accounts payable that are past due (beyond the credit terms given by the vendors and suppliers). Of course, the manager should know the reasons that the accounts have become overdue. The manager may have to personally contact these creditors and convince them to continue offering credit to the business.

Frankly, some businesses operate on the principle of paying late. Their standard operating procedure is to pay their accounts payable two, three, or more weeks after the due dates. This could be due to not having adequate cash balances or wanting to hang on to their cash as long as possible. Years ago, IBM was notorious for paying late, but because its credit rating was unimpeachable, it got away with this policy.

Accrued expenses payable

The controller should prepare a schedule for the manager that lists the major items making up the balance of the accrued expenses payable liability account. Many operating liabilities accumulate or, as accountants prefer to say, accrue during the course of the year that are not paid until sometime later. One main example is employee vacation and sick pay; an employee may work for almost a year before being entitled to take two weeks vacation with pay. The accountant records an expense each payroll period for this employee benefit, and it accumulates in the liability account until the liability is paid (the employee takes his vacation). Another payroll-based expense that accrues is the cost of federal and state unemployment taxes on the employer.

Accrued expenses payable can be a tricky liability from the accounting point of view. There’s a lot of room for management discretion (or manipulation, depending on how you look at it) regarding which particular operating liabilities to record as expense during the year, and which not to record as expense until

Chapter 14: How Business Managers Use a Financial Report 301

they are paid. The basic choice is whether to expense as you go or expense later. If you decide to record the expense as you go through the year, the accountant has to make estimates and assumptions, which are subject to error. Then there’s the question of expediency. Employee vacation and sick pay may seem to be obvious expenses to accrue, but in fact many businesses do not accrue the expense on the grounds that it’s simply too time consuming and, furthermore, that some employees quit and forfeit the rights to their vacations.

Many businesses guarantee the products they sell for a certain period of time, such as 90 days or one year. The customer has the right to return the product for repair (or replacement) during the guarantee period. For example, when I returned my iPod for repair, Apple should have already recorded in a liability account the estimated cost of repairing iPods that will be returned after the point of sale. Businesses have more “creeping” liabilities than you might imagine. With a little work, I could list 20 or 30 of them, but I’ll spare you the details. My main point is that the manager should know what’s in the accrued expenses payable liability account, and what’s not. Also, the manager should have a good fix on when these liabilities will be paid.

Income tax payable

It takes an income tax professional to comply with federal and state income tax laws on business. The manager should make certain that the accountant responsible for its tax returns is qualified and up-to-date.

The controller should explain to the manager the reasons for a relatively large balance in this liability account at the end of the year. In a normal situation, a business should have paid 90 percent or more of its annual income tax by the end of the year. However, there are legitimate reasons that the ending balance of the income tax liability could be relatively large compared with the annual income tax expense — say 20 or 30 percent of the annual expense. It behooves the manager to know the basic reasons for a large ending balance in the income tax liability. The controller should report these reasons to the chief financial officer and perhaps the treasurer of the business.

The manager should also know how the business stands with the IRS, and whether the IRS has raised objections to the business’s tax returns. The business may be in the middle of legal proceedings with the IRS, which the manager should be briefed on, of course. The CEO and (perhaps other top-level managers) should be given a frank appraisal of how things may turn out and whether the business is facing any additional tax payments and penalties. Needless to say, this is very sensitive information, and the controller may prefer that none of it be documented in a written report.

302 Part IV: Preparing and Using Financial Reports

Finally, the chief executive officer working closely with the controller should decide how aggressive to be on income tax issues and alternatives. Keep in mind that tax avoidance is legal, but tax evasion is illegal. As you probably know, the income tax law is exceedingly complex, but ignorance of the law is no excuse. The controller should make abundantly clear to the manager whether the business is walking on thin ice in its income tax returns.

Interest-bearing debt

In Figure 14-1, the balance sheet reports two interest-bearing liabilities: one for short-term debts (those due in one year or less) and one for long-term debt. The reason is that financial reporting standards require that external balance sheets report the amount of current liabilities so the reader can compare this amount of short-term liabilities against the total of current assets (cash and assets that will be converted into cash in the short term). Interest-bearing debt that is due in one year or less is included in the current liabilities section of the balance sheet. (See Chapter 5 for more details.)

The amounts of the short-term and long-term debt accounts reported in the external balance sheet are not enough information for the manager.

The best practice is to lay out in one comprehensive schedule for the manager all the interest-bearing obligations of the business. The obligations should be organized according to their due (maturity) dates, and the schedule should include other relevant information such as the lender, the interest rate on each debt, the plans to roll over the debt (or not), the collateral, and the main covenants and restrictions on the business imposed by the lender.

Recall that debt is one of the two sources of capital to a business (the other being owners’ equity, which I get to next). The sustainability of a business depends on the sustainability of its sources of capital. The more a business depends on debt capital, the more important it is to manage its debt well and maintain excellent relations with its lenders.

Raising and using debt and equity capital, referred to as financial management or corporate finance, is a broad subject that extends beyond the scope of this book. For more information, look at Small Business Financial Management Kit For Dummies (Wiley) — a book that my son, Tage C. Tracy, and I coauthored, which explains the financial management function in more detail.

Chapter 14: How Business Managers Use a Financial Report 303

Owners’ equity

External balance sheets report two kinds of ownership accounts: one for capital invested by the owners in the business and one for retained earnings (profit that has not been distributed to shareowners). In Figure 14-1, just one invested capital account is shown in the owners’ equity section, as if the business has only one class of owners’ equity. In fact, business corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships, and other types of business legal entities can have complex ownership structures. The owners’ equity sections in their balance sheets report several invested capital accounts — one for each class of ownership interest in the business.

Broadly speaking, the manager faces three basic issues regarding the owners’ equity of the business:

Is more capital needed from the owners?

Should some capital be returned to the owners?

Can and should the business make a cash distribution from profit to the owners and, if so, how much?

These questions belong in the field of financial management and extend beyond the scope of this book. However, I should mention that the external financial statements are very useful in deciding these key financial management issues. For example, the manager needs to know how much total capital is needed to support the sales level of the business. The asset turnover ratio (annual sales revenue divided by total assets) provides a good touchstone for determining the amount of capital that is needed for sales.

The external financial report of a business does not disclose the individual shareowners of the business and the number of shares each person or institution owns. The manager may want to know this information. Any major change in the ownership of the business usually is important information to the manager.

Culling Profit Information

The sales and expenses of a business over a period of time are summarized in a financial statement called the income statement. Profit (sales revenue minus expenses) is the bottom line of the income statement. Chapter 4 explains the externally reported income statement, as well as how sales revenue and expenses are interconnected with the operating assets and liabilities of the business. The income statement fits hand in glove with the balance sheet.

304 Part IV: Preparing and Using Financial Reports

Chapter 9 explains internal profit reports to managers, which are called P&L (profit and loss) reports. P&L reports should be designed to help managers in their profit analysis and decision making. Chapter 9 is the logical take-off point for this section, in which I discuss the types of profit information managers need.

Margin: The catalyst of profit

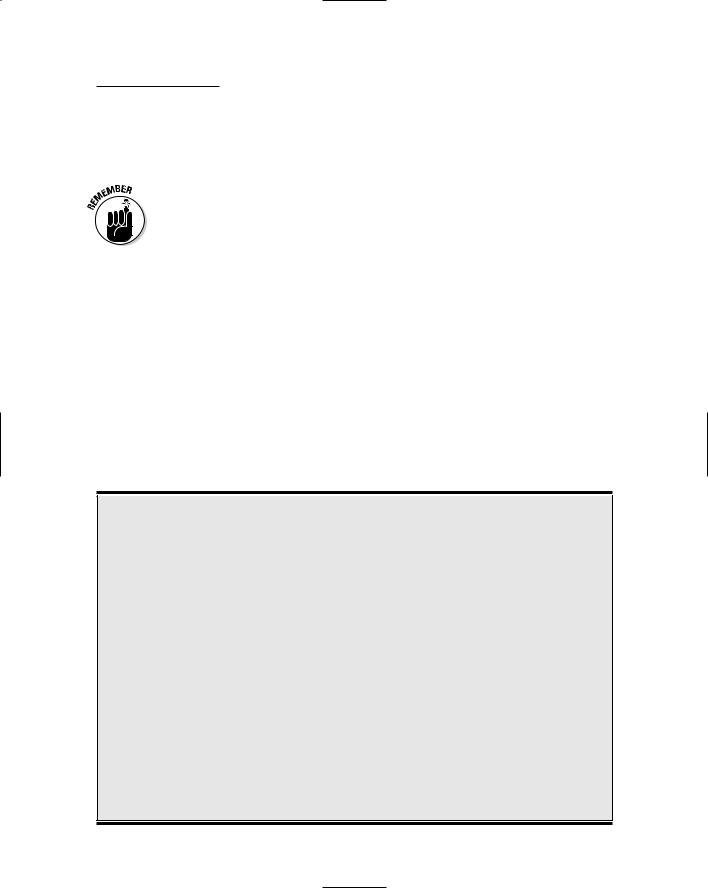

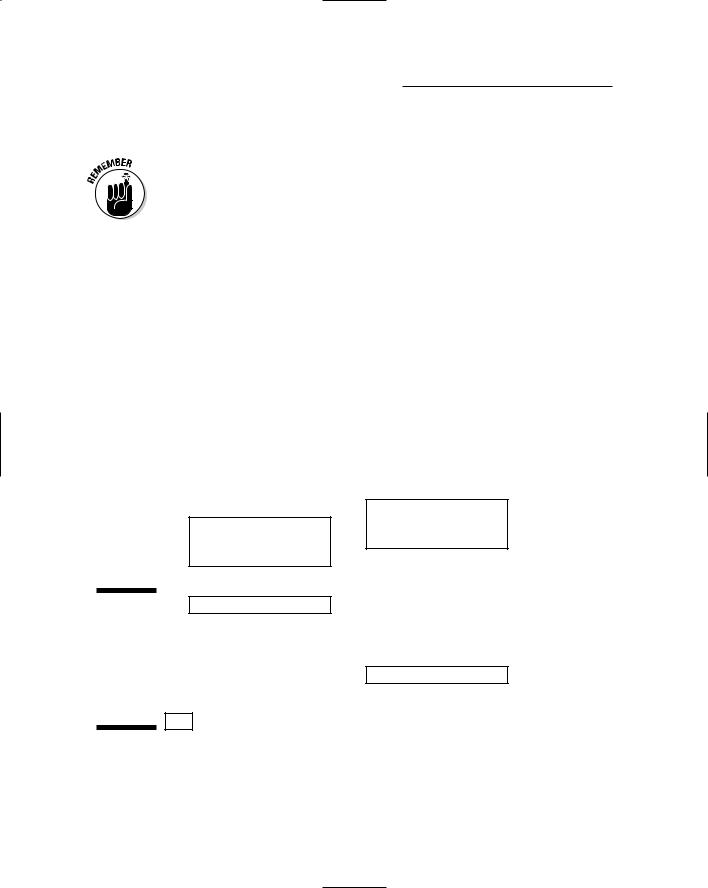

Figure 14-2:

Skeleton of

a P&L (profit

and loss)

report.

A business makes profit by earning total margin that exceeds its total

fixed expenses for the period. Margin equals sales revenue minus all variable expenses of generating the sales revenue. Cost of goods sold is the main variable expense for companies that sell products. Most businesses have other significant variable expenses, which depend either on sales volume (the quantity of products or services sold) or the dollar amount of sales revenue. P&L reports to managers should separate variable from fixed operating expenses, in order to measure margin.

Figure 14-2 presents a skeleton of the P&L report. No dollar amounts are given because I focus on the kinds of information that managers need in order to analyze and control profit. Note that operating expenses below the gross margin line are classified between variable and fixed. Therefore, the P&L report includes margin (profit before fixed operating expenses). Income statements in external financial reports do not classify the behavior of operating expenses.

The P&L report stops at the operating profit line, or earnings before interest and income tax expenses. (Interest is in the hands of the chief financial officer of the business, and income tax is best left to tax professionals.)

Start with |

Sales revenue |

Deduct |

Cost of goods sold expense |

Equals |

Gross margin |

Deduct |

Variable operating expenses |

Equals |

Margin |

Deduct |

Fixed operating expenses |

Equals |

Operating profit* |

* Also called operating earnings, and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)

Chapter 14: How Business Managers Use a Financial Report 305

Most businesses sell a wide variety of products and have many sources of sales revenue. The margins per unit on each source of sales vary. It’s quite unusual to find a business that earns the same margin ratio on all its sales.

The manager needs information on sales revenue and margin for each mainstream source of sales. But the term “mainstream source of sales” will have very different meanings for each business. In analyzing profit, one of the main challenges facing business managers is deciding how to organize, categorize, and aggregate the huge volume of data on sales and expenses.

For example, consider a hardware store in Boulder, Colorado that sells more than 100,000 different products (including different sizes of the same products). Suppose it has ten key managers with sales and profit responsibility. This means that each manager would be responsible for 10,000 different sources of sales. It would be possible to report every specific sale to the manager, but this would be absurd! The same is true for a high-volume retailer like Target or Costco. For a Honda or Toyota auto dealer, on the other hand, reporting each new car sale to the manager would be practical.

Regardless of how sales are reported to the manager, all variable expenses of each sales source should be matched against the sales revenue in order to determine margin for that source. The alternative is to match only the cost of goods sold expense with sales revenue, which means that the manager knows only gross margin instead of final margin (after variable operating expenses are also deducted from sales revenue).

Sales revenue and expenses

In this section, I offer examples of sales revenue and expense information that managers need that is not reported in the external income statement of a business. Given the very broad range of different businesses and different circumstances, I can’t offer much detail.

Here’s a sampling of the kinds of accounting information that business managers need either in their P&L reports or in supplementary schedules and analyses:

Sales volumes (quantities sold) for all sources of sales revenue.

List sales prices and discounts, allowances, and rebates against list sales prices. For many businesses (but not all), sales pricing is a twosided affair that starts with list prices (such as manufacturer’s suggested retail price) and includes deductions of all sorts from the list prices.

Sales returns — products that were bought but later returned by customers.

Special incentives offer by suppliers that effectively reduce the purchase cost of products.

306 Part IV: Preparing and Using Financial Reports

Abnormal charges for embezzlement and fraud losses.

Significant variations in discretionary expenses from year to year, such as repair and maintenance, employee training costs, and advertising.

Illegal payments to secure business, including bribes, kickbacks, and other under-the-table payments. Keep in mind that businesses are not willing to admit to making such payments, much less report them in internal communications. Therefore, the manager should know how these payments are disguised in the accounts of the business.

Sales revenue and margin for new products.

Significant changes in fixed costs and reasons for the changes.

Expenses that surged much more than increases in sales volume or sales revenue.

New expenses that show up for first time.

Accounting changes (if any) regarding when sales revenue and expenses are recorded.

The above items do not constitute an exhaustive list. But the list covers many important types of information that managers need in order to interpret their P&L reports and to plan profit improvements in the future. Analyzing profit is a very open-ended process. There are many ways to slice and dice sales and expense data. Managers have only so much time at their disposal, but they should take the time to understand and analyze the main factors that drive profit.

Digging into Cash Flow Information

Chapter 6 explains the statement of cash flows included in a business’s external financial report. Cash flows are divided into three types:

Cash flows from operating activities (“operating” refers to making sales and incurring expenses in the process of earning profit)

Cash flows from investing activities (outlays for new long-term assets and proceeds from disposals of these assets)

Cash flows from financing activities (borrowing and repaying debt; raising capital from and returning capital to owners; and cash distributions from profit to owners)

Chapter 14: How Business Managers Use a Financial Report 307

Distinguishing investing and financing cash flows from operating cash flows

Investing and financing decisions are the heart of business financial management. Every business must secure and invest capital. No capital, no business — it’s as simple as that. Inadequate capital clamps limits on the growth potential of a business. In larger businesses, the financing and investing activities are the domain of the chief financial officer (CFO), who works with other high-level executives in setting the financial strategies and policies of the business.

The field of financial management — raising capital for a business and deploying its capital — is beyond the scope of this book. For more information, you can refer to the book I coauthored with my son, Small Business Financial Management Kit For Dummies (Wiley).

This section concentrates on cash flow from operating activities. These cash flows are in the domain of managers with operating responsibilities — managers who have responsibilities for sales and the expenses that are directly connected with making sales. These managers should understand the cash flow impacts of their sales and expenses. (See the sidebar “Cash flow characteristics of sales and expenses.”) Their sales and expense decisions drive the operating activity cash flows of the business.

Cash flow characteristics of sales and expenses

In reading their P&L reports, managers should keep in mind that the accountant records sales revenue when sales are made — regardless of when cash is received from customers. Also, the accountant records expenses to match expenses with sales revenue and to put expenses in the period where they belong — regardless of when cash is paid for the expenses. The manager should not assume that sales revenue equals cash inflow, and that expenses equal cash outflow.

The cash flow characteristics of sales and expenses are summarized as follows:

Cash sales generate immediate cash inflow. Keep in mind that sales returns and sales price adjustments after the point of sale reduce cash flow.

Credit sales do not generate immediate cash inflow. There’s no cash flow until the customers’ receivables are actually collected. There’s a cash flow lag from credit sales.

Many operating costs are not paid until several weeks (or months) after they are recorded as expense; and a few operating costs are paid before the costs are charged to expense.

Depreciation expense is recorded by reducing the book value of an asset and does not involve cash outlay in the period when it is recorded. The business paid out cash when the asset was acquired. (Amortization expense on intangible assets is the same.)

308 Part IV: Preparing and Using Financial Reports

Managing operating cash flows

In a small, one-owner/one-manager business, one person has to manage both profit and cash flow from profit. In larger businesses, managers who have profit responsibility may or may not have cash flow responsibility. The profit manager may ignore the cash flow aspects of his sales and expense activities. The responsibility for controlling cash flow falls on some other manager. Of course, someone should manage the cash flows of sales and expenses. The following comments speak to this person in particular.

The net cash flow during the period from carrying on profit-making operations depends on the changes in the operating assets and liabilities directly connected with sales revenue and expenses. Figure 14-3 highlights these assets and liabilities, and also retained earnings. Changes in these accounts during the year determine the cash flow from operating activities. In other words, changes in these accounts boost or crimp cash flow.

Note that retained earnings is highlighted in Figure 14-3. Profit increases this owners’ equity account. Profit is the starting point for determining cash flow from operating activities. (Alternatively, a business may use the direct method for determining and reporting cash flow from operating activities, which I explain in Chapter 6.)

Figure 14-3:

Assets and liabilities affecting cash flow from operating activities.

Assets

Cash

Accounts receivable Inventory

Prepaid expenses

Fixed assets

Accumulated depreciation

Liabilities

Accounts payable Accrued expenses payable Income tax payable

Short-term notes payable

Long-term notes payable

Owners’ Equity

Invested capital

Retained earnings

Changes in these accounts affect cash flow from operating activities.

Chapter 14: How Business Managers Use a Financial Report 309

The cash flow from profit is determined as follows:

1.Start with the accounting profit number, usually labeled net income.

2.Add depreciation expense (and amortization expense, if any) because there is no cash outlay for the expense during the period.

3.Deduct increases or add decreases in operating assets because

•An increase requires additional cash outlay to build up the asset.

•A decrease means part of the asset is liquidated and provides cash.

4.Add increases or deduct decreases in operating liabilities because

•An increase means less cash is paid out than the expense.

•A decrease means more cash is paid out to reduce the liability.

You may ask: What about changes during the year in those balance sheet accounts that are not highlighted in Figure 14-3? Well, these changes are reported either in the cash flow from investing activities or the cash flow from financing activities sections of the statement of cash flows. So, all balance sheet account changes during the year end up in the statement of cash flows.

The manager should closely monitor the changes in operating assets and liabilities (see Figure 14-3). A good general rule is that each operating asset and liability should change about the same percent as the percent change in the sales activity of the business. If sales revenue increases, say, 10 percent, then operating assets and liabilities should increase about 10 percent. The percents of increases in the operating assets and liabilities (in particular, accounts receivable, inventory, accounts payable, and accrued expenses payable) should be emphasized in the cash flow report to the manager. The manager should not have to take out his calculator and do these calculations.

Controlling cash flow from profit (operating activities) means controlling changes in the operating assets and liabilities of making sales and incurring expenses: There’s no getting around this fact of business life. There’s no doubt that cash flow is king. You can be making good profit, but if you don’t turn the profit into cash flow quickly, you are headed for big trouble.