Accounting For Dummies, 4th edition

.pdf

220 Part III: Accounting in Managing a Business

|

|

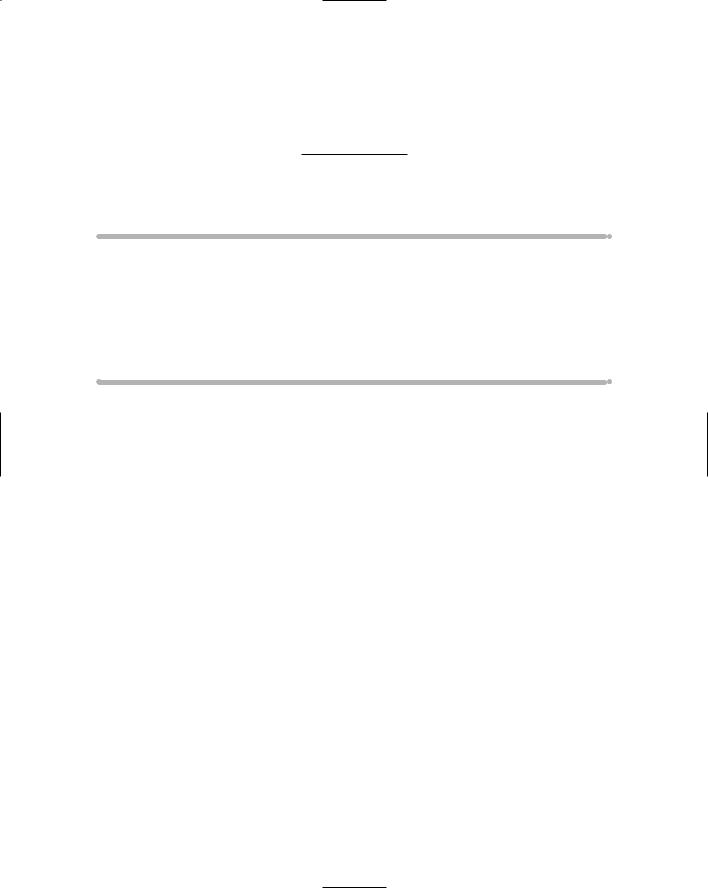

Budgeted profit (See Figure 10-2) |

$2,856,000 |

|

|

|

|

Accounts receivable increase |

(195,574) |

||

|

|

||||

Figure 10-3: |

|||||

Inventory increase |

(317,095) |

||||

Budgeted |

|||||

|

|

|

|||

cash flow |

Prepaid expenses increase |

(26,226) |

|||

from |

Depreciation expense |

835,000 |

|

||

operating |

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

activities |

Accounts payable increase |

34,968 |

|

||

for the |

Accrued expenses payable increase |

52,453 |

|

||

coming |

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

year. |

Budgeted cash flow from operating profit |

$3,239,526 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You submit this budgeted cash flow from operating activities (see Figure 10-3) to headquarters. Top management expects you to control the increases in your operating assets and liabilities so that the actual cash flow generated by your division next year comes in on target. The cash flow of your division (minus, perhaps, a small amount needed to increase the working cash balance held by your division) will be transferred to the central treasury of the business. Headquarters will be planning on you generating about $3.2 million cash flow during the coming year.

Considering Capital Expenditures

and Other Cash Needs

This chapter focuses on profit budgeting for the coming year and budgeting the cash flow from that profit. These are the two hardcore components of business budgeting, but not the whole story. Another key element of the budgeting process is to prepare a capital expenditures budget for your division that goes to top management for review and approval. A business has to take a hard look at its long-term operating assets — in particular, the capacity, condition, and efficiency of these resources — and decide whether it needs to expand and modernize its property, plant, and equipment.

In most cases, a business needs to invest substantial sums of money in purchasing new fixed assets or retrofitting and upgrading its old fixed assets. These long-term investments require major cash outlays. So, each division of a business prepares a formal list of the fixed assets to be purchased, constructed, and upgraded. The money for these major outlays comes from the central treasury of the business. Accordingly, the overall capital expenditures

Chapter 10: Financial Planning, Budgeting, and Control 221

budget goes to the highest levels in the organization for review and final approval. The chief financial officer, the CEO, and the board of directors of the business go over a capital expenditure budget request with a fine-toothed comb (or at least they should).

At the company-wide level, the financial officers merge the profit and cash flow budgets of all profit centers and cost centers of the business. (A cost center is an organizational unit that does not generate revenue, such as the legal and accounting departments.) The budgets submitted by one or more of the divisions may be returned for revision before final approval is given. One main concern is whether the collective cash flow total from all the units provides enough money for the capital expenditures that will be made during the coming year — and to meet the other demands for cash, such as for cash distributions from profit. The business may have to raise more capital from debt or equity sources during the coming year to close the gap between cash flow from operating activities and its needs for cash. This is a central topic in the field of business finance and beyond the coverage of this book.

Business budgeting versus government budgeting: Only the name is the same

Business and government budgeting are more different than alike. Government budgeting is preoccupied with allocating scarce resources among many competing demands. From federal agencies down to local school districts, government entities have only so much revenue available. They have to make very difficult choices regarding how to spend their limited tax revenue.

Formal budgeting is legally required for almost all government entities. First, a budget request is submitted. After money is appropriated, the budget document becomes legally binding on the government agency. Government budgets are legal straitjackets; the government entity

has to stay within the amounts appropriated for each expenditure category. Any changes from the established budgets need formal approval and are difficult to get through the system.

A business is not legally required to use budgeting. A business can implement and use its budget as it pleases, and it can even abandon its budget in midstream. Unlike the government, the revenue of a business is not constrained; a business can do many things to increase sales revenue. A business can pass its costs to its customers in the sales prices it charges. In contrast, government has to raise taxes to spend more (except for federal deficit spending, of course).

222 Part III: Accounting in Managing a Business

Chapter 11

Cost Concepts and Conundrums

In This Chapter

Determining costs: The second most important thing accountants do

Appreciating the different needs for cost information

Contrasting costs for understanding them better

Determining product cost for manufacturers

Padding profit by manufacturing too many products

Measuring costs is the second most important thing accountants do, right after measuring profit. (Well, the Internal Revenue Service might

think that measuring taxable income is the most important.) But really, can measuring a cost be very complicated? You just take numbers off a purchase invoice and call it a day, right? Not if your business manufactures the products you sell — that’s for sure! In this chapter, I demonstrate that a cost, any cost, is not as obvious and clear-cut as you may think. Yet, obviously, costs are extremely important to businesses and other organizations.

Consider an example close to home: Suppose you just returned from the grocery store with several items in the bag. What’s the cost of the loaf of bread you bought? Should you include the sales tax? Should you include the cost of gas you used driving to the store? Should you include some amount of depreciation expense on your car? Suppose you returned some aluminum cans for recycling while you were at the grocery store, and you were paid a small amount for the cans. Should you subtract this amount against the total cost of your purchases? Or should you subtract the amount directly against the cost of only the sodas in aluminum cans that you bought? And, is cost the before-tax cost? In other words, is your cost equal to the amount of income you had to earn before income tax so that you had enough after-tax income to buy the items?

These questions about the cost of your groceries are interesting (well, to me at least). But you don’t really have to come up with definite answers for such questions in managing your personal financial affairs. Individuals don’t have to keep cost records of their personal expenditures, other than what’s needed for their annual income tax returns. In contrast, businesses must carefully record all their costs correctly so that profit can be determined each period, and so that managers have the information they need to make decisions and to make a profit.

224 Part III: Accounting in Managing a Business

Looking down the Road to the Destination of Costs

All businesses that sell products must know their product costs — in other words, the costs of each and every item they sell. Companies that manufacture the products they sell — as opposed to distributors and retailers of products — have many problems in figuring out their product costs. Two examples of manufactured products are a new Cadillac just rolling off the assembly line at General Motors and a copy of my book, Accounting For Dummies, 4th Edition, hot off the printing presses.

Most production (manufacturing) processes are fairly complex, so product cost accounting for manufacturers is fairly complex; every step in the production process has to be tracked carefully from start to finish. Many manufacturing costs cannot be directly matched with particular products; these are called indirect costs. To arrive at the full cost of each product manufactured, accountants devise methods for allocating indirect production costs to specific products. Surprisingly, generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) provide very little authoritative guidance for measuring product cost. Therefore, manufacturing businesses have more than a little leeway regarding how to determine their product costs. Even businesses in the same industry — Ford versus General Motors, for example — may use different product cost accounting methods.

Accountants determine many other costs, in addition to product costs:

The costs of departments, regional distribution centers, and other organizational units of the business

The cost of the retirement plan for the company’s employees

The cost of marketing programs and advertising campaigns

The cost of restructuring the business or the cost of a major recall of products sold by the business, when necessary

A common refrain among accountants is “different costs for different purposes.” True enough, but at its core, cost accounting serves two broad purposes: measuring profit and providing relevant information to managers for planning, control, and decision-making.

In my experience, people are inclined to take cost numbers for granted, as if they were handed down on stone tablets. The phrase actual cost often gets tossed around without a clear definition. An actual cost depends entirely on the particular methods used to measure the cost. I can assure you that these cost measurement methods have more in common with the scores from judges in an ice skating competition than the times clocked in a Formula One auto race. Many arbitrary choices are behind every cost number you see.

Chapter 11: Cost Concepts and Conundrums 225

There’s no one-size-fits-all definition of cost, and there’s no one correct and “best-in-all-circumstances” method of measuring cost.

The conundrum is that, in spite of the inherent ambiguity in determining costs, we need exact amounts for costs. In order to understand the income statement and balance sheet that managers use in making their decisions, they need to understand a little bit about the choices an accountant has to make in measuring costs. Some cost accounting methods result in conservative profit numbers; other methods boost profit, at least in the short run.

This chapter covers cost concepts and cost measurement methods that apply to all businesses, as well as basic product cost accounting of manufacturers. I discuss how a manufacturer could be fooling around with its production output to manipulate product cost for the purpose of artificially boosting its profit figure. (Service businesses encounter their own problems in allocating their operating costs for assessing the profitability of their separate sales revenue sources.)

Are Costs Really That Important?

Without good cost information, a business operates in the dark. Cost data is needed for the following purposes:

Setting sales prices: The common method for setting sales prices (known as cost-plus or markup on cost) starts with cost and then adds a certain percentage. If you don’t know exactly how much a product costs, you can’t be as shrewd and competitive in your pricing as you need to be. Even if sales prices are dictated by other forces and not set by managers, managers need to compare sales prices against product costs and other costs that should be matched against each sales revenue source.

Formulating a legal defense against charges of predatory pricing practices: Many states have laws prohibiting businesses from selling below cost except in certain circumstances. And a business can be sued under federal law for charging artificially low prices intended to drive its competitors out of business. Be prepared to prove that your lower pricing is based on lower costs and not on some illegitimate purpose.

Measuring gross margin: Investors and managers judge business performance by the bottom-line profit figure. This profit figure depends on the gross margin figure you get when you subtract your cost of goods sold expense from your sales revenue. Gross margin (also called gross profit) is the first profit line in the income statement (see Figures 4-1 and 9-1, as well as Figure 11-1 later in this chapter, for examples). If gross margin is wrong, bottom-line net income is wrong — no two ways about it. The cost of goods sold expense depends on having correct product costs (see “Assembling the Product Cost of Manufacturers” later in this chapter).

226 Part III: Accounting in Managing a Business

Valuing assets: The balance sheet reports cost values for many (though not all) assets. To understand the balance sheet you should understand the cost basis of its inventory and certain other assets. See Chapter 5 for more about assets and how asset values are reported in the balance sheet (also called the statement of financial condition).

Making optimal choices: You often must choose one alternative over others in making business decisions. The best alternative depends heavily on cost factors, and you have to be careful to distinguish relevant costs from irrelevant costs, as I describe in the section “Relevant versus irrelevant costs,” later in this chapter.

In most situations, the book value of a fixed asset is an irrelevant cost. Say book value is $35,000 for a machine used in the manufacturing operations of the business. This is the amount of original cost that has not yet been charged to depreciation expense since it was acquired, and it may seem quite relevant. However, in deciding between keeping the old machine or replacing it with a newer, more efficient machine, the disposable value of the old machine is the relevant amount, not the undepreciated cost balance of the asset. Suppose the old machine has only a $20,000 salvage value at this time; this is the relevant cost for the alternative of keeping it for use in the future — not the $35,000 that hasn’t been depreciated yet. In order to keep using it, the business forgoes the $20,000 it could get by selling the asset, and this $20,000 is the relevant cost in this decision situation. Making decisions involves looking forward at the future cash flows of each alternative — not looking backward at historical-based cost values.

Becoming More Familiar with Costs

The following sections explain important cost distinctions that managers should understand in making decisions and exercising control. Also, these cost distinctions help managers better appreciate the cost figures that accountants attach to products that are manufactured or purchased by the business.

Retailers (such as Wal-Mart or Costco) purchase products in a condition ready for sale to their customers — although the products have to be removed from shipping containers, and a retailer does a little work making the products presentable for sale and putting the products on display. Manufacturers don’t have it so easy; their product costs have to be “manufactured” in the sense that the accountants have to accumulate various production costs and compute the cost per unit for every product manufactured. I focus on the special cost concerns of manufacturers in the upcoming section “Assembling the Product Cost of Manufacturers.”

Chapter 11: Cost Concepts and Conundrums 227

Accounting versus economic costs

Accountants focus mainly on actual costs (though they disagree regarding how exactly to measure these costs). Actual costs are rooted in the actual, or historical, transactions and operations of a business. Accountants also determine budgeted costs for businesses that prepare budgets (see Chapter 10), and they develop standard costs that serve as yardsticks to compare with the actual costs of a business.

Other concepts of cost are found in economic theory. You encounter a variety of economic cost terms when reading The Wall Street Journal, as well as in many business discussions and deliberations. Don’t reveal your ignorance of the following cost terms:

Opportunity cost: The amount of income (or other measurable benefit) given up when you follow a better course of action. For example, say that you quit your $50,000 job, invest $200,000 to start a new business, and end up netting $80,000 in your new business for the year. Suppose also that you would have earned 5 percent on the $200,000 (a total of $10,000) if you’d kept the money in whatever investment you took it from. So you gave up a $50,000 salary and $10,000 in investment income with your course of action; your opportunity cost is $60,000. Subtract that figure from what your actual course of action netted you — $80,000 — and you end up with a “real” economic profit of $20,000. Your income is $20,000 better by starting your new business according to economic theory.

Marginal cost: The incremental, out-of- pocket outlay required for taking a particular course of action. Generally speaking, it’s the same thing as a variable cost (see “Fixed versus variable costs,” later in this chapter). Marginal costs are important, but in actual practice managers must recover fixed (or nonmarginal) costs as well as marginal costs through sales revenue in order

to remain in business for any extent of time. Marginal costs are most relevant for analyzing one-time ventures, which don’t last over the long-term.

Replacement cost: The estimated amount it would take today to purchase an asset that the business already owns. The longer ago an asset was acquired, the more likely its current replacement cost is higher than its original cost. Economists are of the opinion that current replacement costs are relevant in making rational economic decisions. For insuring assets against fire, theft, and natural catastrophes, the current replacement costs of the assets are clearly relevant. Other than for insurance, however, replacement costs are not on the front burners of decision-making — except in situations in which one alternative being seriously considered actually involves replacing assets.

Imputed cost: An ideal, or hypothetical, cost number that is used as a benchmark or yardstick against which actual costs are compared. Two examples are standard costs and the cost of capital. Standard costs are set in advance for the manufacture of products during the coming period, and then actual costs are compared against standard costs to identify significant variances. The cost of capital is the weighted average of the interest rate on debt capital and a target rate of return that should be earned on equity capital. The economic value added (EVA) method compares a business’s cost of capital against its actual return on capital, to determine whether the business did better or worse than the benchmark.

For the most part, these types of cost aren’t reflected in financial reports. I’ve included them here to familiarize you with terms you’re likely to see in the financial press and hear on financial talk shows. Business managers toss these terms around a lot.

228 Part III: Accounting in Managing a Business

I cannot exaggerate the importance of correct product costs (for businesses that sell products, of course). The total cost of goods (products) sold is the first, and usually the largest, expense deducted from sales revenue in measuring profit. The bottom-line profit amount reported in a business’s income statement depends heavily on whether its product costs have been measured properly during that period. Also, keep in mind that product cost is the value for the inventory asset reported in the balance sheet of a business. (For a balance sheet example see Figure 5-2.)

Direct versus indirect costs

You might say that the starting point for any sort of cost analysis, and particularly for accounting for the product costs of manufacturers, is to clearly distinguish between direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are easy to match with a process or product, whereas indirect costs are more distant and have to be allocated to a process or product. Here are more details:

Direct costs: Can be clearly attributed to one product or product line, or one source of sales revenue, or one organizational unit of the business, or one specific operation in a process. An example of a direct cost in the book publishing industry is the cost of the paper that a book is printed on; this cost can be squarely attached to one particular phase of the book production process.

Indirect costs: Are far removed from and cannot be naturally attached to specific products, organizational units, or activities. A book publisher’s phone bill is a cost of doing business but can’t be tied down to just one step in the book editorial and production process. The salary of the purchasing officer who selects the paper for all the books is another example of a cost that is indirect to the production of particular books.

Each business must determine a method of allocating indirect costs to different products, sources of sales revenue, organizational units, and so on. Most allocation methods are far from perfect and, in the final analysis, end up being arbitrary to one degree or another. Business managers should always keep an eye on the allocation methods used for indirect costs and take the cost figures produced by these methods with a grain of salt. If I were called in as an expert witness in a court trial involving costs, the first thing I’d do is critically analyze the allocation methods used by the business for its indirect costs. If I were on the side of the defendant, I’d do my best to defend the allocation methods. If I were on the side of the plaintiff, I’d do my best to discredit the allocation methods — there are always grounds for criticism.

Chapter 11: Cost Concepts and Conundrums 229

The cost of filling the gas tank as I drive from Denver to San Diego and back to consult with my coauthor and son, Tage, about the book we wrote together, Small Business Financial Management Kit For Dummies (Wiley), is a direct cost of making the trip. The annual auto license plate fee that I pay to the state of Colorado is an indirect cost of the trip, although it is a direct cost of having the car available during the year.

Fixed versus variable costs

If your business sells 100 more units of a certain item, some of your costs increase accordingly, but others don’t budge one bit. This distinction between variable and fixed costs is crucial:

Variable costs: Increase and decrease in proportion to changes in sales or production level. Variable costs generally remain the same per unit of product, or per unit of activity. Additional units manufactured or sold cause variable costs to increase in concert. Fewer units manufactured or sold result in variable costs going down in concert.

Fixed costs: Remain the same over a relatively broad range of sales volume or production output. Fixed costs are like a dead weight on the business. Its total fixed costs for the period are a hurdle it must overcome by selling enough units at high enough margins per unit in order to avoid a loss and move into the profit zone. (Chapter 9 explains the break-even point, which is the level of sales needed to cover fixed costs for the period.)

Note: The distinction between variable and fixed costs is essential for understanding and analyzing profit behavior, which I explain in Chapter 9.

Relevant versus irrelevant costs

Not every cost is important to every decision a manager needs to make. Hence the distinction between relevant and irrelevant costs:

Relevant costs: Costs that should be considered and included in your analysis when deciding on a future course of action. Relevant costs are future costs — costs that you would incur, or bring upon yourself, depending on which course of action you take. For example, say that you want to increase the number of books that your business produces next year in order to increase your sales revenue, but the cost of paper has just shot up. Should you take the cost of paper into consideration? Absolutely — that cost will affect your bottom-line profit and may negate any increase in sales volume that you experience (unless you increase the sales price). The cost of paper is a relevant cost.